Some dictators manage to usurp control of decision-making and political appointments at the expense of their top allies. Personalism, the result of this process, is a crucial underlying dimension of autocratic rule that varies across regimes and, importantly, can rise (or fall) during a dictator's tenure (Geddes, Wright, and Frantz (GWF) 2018; Wright Reference Wright2021). Scholars have convincingly shown that personalist regimes lead to a panoply of dangers.Footnote 1 With elites increasingly unable to constrain them, these leaders often become more erratic, internationally belligerent, corrupt, and brutal. Muammar Gaddafi, Libya's former leader, for example, sponsored international terrorism, intervened militarily in Chad, sought to acquire nuclear weapons, and increasingly relied on extrajudicial executions and torture. He was eventually ousted (and killed) in a bloody civil war.

Far from being a Cold War relic, personalist rule is on the rise today (Kendall-Taylor, Frantz, and Wright Reference Kendall-Taylor, Frantz and Wright2017). However, our understanding of the conditions under which dictators such as Gaddafi manage to concentrate power is still limited; many questions linger about how and, especially, ‘when’ dictators personalize power. The main obstacle to dictators’ ambitions is that elites, interested in maintaining collegiality, try to deter them by staging (or threatening to stage) a coup. Accounts for the emergence of personalism must then provide explanations about how dictators can escape such control. Some suggest that dictators can circumvent it by concentrating power gradually through cumulative, subtle power grabs (Svolik Reference Svolik2012). Yet, many personalizing moves, such as appointing loyalists or creating paramilitary units, are highly noticeable to elites. Others focus on structural factors that put the dictator in an advantageous position vis-à-vis the elites, such as the conditions at the time the ruler takes over (Geddes, Wright, and Frantz Reference Geddes, Wright and Frantz2018; Meng Reference Meng2020; Sudduth Reference Sudduth2017), the availability of oil rents (Fails Reference Fails2019), or the support of foreign allies (Boutton Reference Boutton2019; Casey Reference Casey2020). These approaches, however, cannot inform us about the impact of contextual changes in internal power dynamics and, hence, about the timing of rapid, sharp increases in power concentration even years after the dictator seized power.

We address these gaps and claim that personalism can also emerge via punctuated equilibrium following certain disruptive events. In particular, we argue that failed coups – being overt and irregular challenges originating from inside the regime normally involving members of the security forces – are unique shocks that can usher in an advantageous context for visible and sharp increases in personalism. Coups thus represent ‘critical junctures’ (Capoccia and Kelemen Reference Capoccia and Kelemen2007) that, by altering the power dynamics between the dictator and the ruling coalition, reshape the political and institutional trajectories of the polities where they occur. By contrast, other threats emanating from outside the regime (such as failed assassination attempts and civil war onsets) do not create the same opportunities for dictators to rush to personalize.

In recent years, a lively scholarly debate has emerged about the potential democratizing effects of successful coups (Derpanopoulos et al. Reference Derpanopoulos2016; Marinov and Goemans Reference Marinov and Goemans2014; Miller Reference Miller2021; Thyne and Powell Reference Thyne and Powell2016; Varol Reference Varol2017). However, more often than not, coup makers fail to seize power. According to the Colpus dataset (Chin, Carter, and Wright Reference Chin, Carter and Wright2021), about half of all coup attempts staged since 1946 failed to unseat the incumbents. Despite this, and the fact that nearly three-quarters of coup attempts occur in dictatorships, scholars have only started to examine the consequences of failed coups. A few prior studies explored how failed coups influenced outcomes such as state repression and elite purges (Bokobza et al. Reference Bokobza2022; Curtice and Arnon Reference Curtice and Arnon2020; Oztig and Donduran Reference Oztig and Donduran2020). Less attention was paid to whether failed coups can have lasting consequences that reshape the nature, power distribution, and functioning of autocratic regimes.

After failed coups, some suggest that dictators will broaden their coalition to placate opposition (Thyne and Powell Reference Thyne and Powell2016), while others show that a regime change rarely follows a failed attempt (Derpanopoulos et al. Reference Derpanopoulos2016). In contrast, we argue that failed coups can (and often do) lead dictators to transform the structure of autocratic regimes in the opposite direction, a power accumulation process that research, using data on full regime transitions (to democracy or a new dictatorship) or repression, cannot capture. Specifically, we posit that failed coups in autocratic regimes act as strong contingent catalysts of personalization.

Consider, again, the case of Libya. In September 1969, a group of young army officers led by Muammar Gaddafi toppled the ruling monarchy in a coup. Gaddafi initially ruled as the chairman of a collegial body, the Revolutionary Command Council (RCC), which had twelve members, all of whom were military officers whose membership remained more or less fixed through the mid-1970s. In 1972, Gaddafi relinquished the premiership to another RCC member, Major Jallud: In 1974, Gaddafi even gave up his remaining administrative portfolio to focus on revolutionary theorizing. Though he remained the armed forces’ commander-in-chief, Gaddafi's power appeared to be on the wane (Berry Reference Berry and Metz1989, 45–6). This dynamic completely changed in 1975, when an anti-Qaddafi RCC faction and several army officers organized a coup that failed. Gaddafi's reaction was swift and drastic. He proceeded to marginalize the RCC, the regime's official party since 1971, and the Arab Socialist Union (ASU), the two institutions that had the collective capacity to constrain him. With its technocratic wing purged (St. John Reference St. John2015), the RCC was reduced in number from twelve to five members. After creating a more pliant General People's Congress (St. John Reference St. John2014, 161, 247), the RCC was formally abolished in 1977 (Feliu and Aarab Reference Feliu and Aarab2019, 79). As for the security apparatus, the 1975 coup ‘marked the end of professional and technical criteria for military recruitment and was the beginning of a steady but noticeable influx of individual members of Qadhafi's tribe – and later of his family – into sensitive security and army positions’ (Vandewalle Reference Vandewalle1998, 88). Still, in August 1980, Gaddafi was only able to crush a bloody coup attempt by an air force unit, based at Tobruq, with the help of East German military advisers (Cooley Reference Cooley1982, 282). In response, in the early to mid-1980s Gaddafi counterbalanced the regular armed forces by mobilizing armed ‘revolutionary committees’ (Pollack Reference Pollack2002, 386) and by creating multiple overlapping paramilitary units such as the Jamahiriyyah Guard and a special brigade led by his son (Lutterbeck Reference Lutterbeck2013). Following yet another failed coup in October 1993, which implicated members of the previously-allied Warfalla tribe, Qaddafi relied exclusively on the Jamahiriyyah Guard for regime protection (Gaub Reference Gaub2013, 229). He further emphasized tribal loyalty to cement his hold on power (Baxley Reference Baxley2011, 6). Through these actions taken largely in the wake of failed coups, Gaddafi successfully and completely personalized power, and ruled largely unconstrained until 2011.

Our argument rests on the premise that dictators have an interest in accumulating power while the ruling coalition seeks the opposite. In this tug-of-war, failed coups alter the information environment and create both incentives and opportunities for the dictator to escape the elites’ control. First, by signalling the existence of inside threats, failed coups incentivize rulers to take action to prevent further challenges and avoid costly post-exit punishments. Second, surviving a coup attempt undermines, at least temporarily, the credibility and deterrent effect of elite threats. By revealing information about the loyalty of members and factions in the ruling coalition, failed coups allow dictators to identify and eliminate rivals while also limiting the remaining elites' motives to challenge their position. Using new data on coups and a time-varying latent measure of personalism in dictatorships in 114 countries worldwide between 1946 and 2010, our empirical analyses support our theoretical expectations. We provide descriptive, quantitative evidence and probe the causal effect of failed coups on personalization using a synthetic control approach. Further, we illustrate the plausibility of our arguments with three case studies of post-coup trajectories in Algeria (1967), Sierra Leone (1971), and Benin (1975).

By examining the coup-personalism relationship, this article bridges and contributes to two strands of literature within comparative authoritarianism. First, we expand our understanding of the pathways to personalist rule. Most existing work focuses on constant or slow-moving factors that create favourable conditions for dictators. We also show that certain shocks can alter the dynamic structure of incentives and opportunities for the relevant actors and explain the substantial variation over time in personalism and, concretely, the occurrence of large surges within leaders' tenure. Second, we expand the burgeoning literature examining the impact of failed coups. Existing works have so far focused on repression, (elite or military) purges, or discrete regime changes but not on the full extent to which the dictator has individual discretion over the key levers of power. Repression, an outcome endogenous to regime structures, is conceptually different from personalism. And purges, while often viewed as entailing power consolidation, are just one among several items used in constructing the latent measure of personalism we use in this article. The measure, rather than regime change, captures an evolving trait of all autocracies.

Extant Work

Prior work on personalism mostly relied on the Geddes (Reference Geddes1999) and Geddes, Wright, and Frantz (Reference Geddes, Wright and Frantz2014) regime typology, which comparativists have used extensively to explore how different forms of dictatorship affect a wide range of political and economic outcomes. Because they are time-invariant within a given regime, these categories are less useful for studying how different forms of authoritarian rule emerge and how levels of personalism change within regimes.Footnote 2 New work by Geddes, Wright, and Frantz (Reference Geddes, Wright and Frantz2018) and Wright (Reference Wright2021) reconceives personalism as a continuous trait of all autocratic rule, not just one regime type. As such, personalization may occur in varying degrees in any regime and, importantly, can vary over time.

The literature on the emergence of personalism is rather limited despite the dangers associated with this form of rule and its growing global importance. The consensus is that power aggrandizement only happens when some factor gives the dictator a bargaining advantage over the elites so that the latter are less able to monitor or punish him via a coup. Thus, the first pathway to personalist rule, according to Svolik (Reference Svolik2009, Reference Svolik2012), opens when the threat of a coup lacks sufficient credibility because costly coups might be reconsidered due to the imperfect nature of observed signals of a dictator's opportunism. Personalism, under such circumstances, occurs gradually and is abetted by secrecy.

According to some highly structural accounts, a second pathway opens when dictators' advantages stem from time-invariant or slow-moving factors such as initial conditions, natural resources, or foreign support. Concerning initial conditions, Meng (Reference Meng2020) argues that strong leaders, namely post-colonial founding presidents and those coming to power via a coup, are unlikely to institutionalize their regimes due to their higher popularity and their control over the security forces, respectively. Similarly, Sudduth (Reference Sudduth2017) claims that leaders who seize power via a coup – and head a loyal coalition that replaces entirely the prior one – are more likely to purge rivals in the first few years of their tenure. Alternatively, Geddes, Wright, and Frantz (Reference Geddes, Wright and Frantz2018) focus on the initial internal cohesion of seizure groups. They claim that factionalized elites cannot obstruct ‘the dictator's drive to concentrate power’ while ‘the dictator can bargain separately with each member of a factionalized seizure group’, inducing competition and driving down the price of support (Geddes, Wright, and Frantz Reference Geddes, Wright and Frantz2018, 78–9). As for other structural factors, Fails (Reference Fails2019) shows that increases in oil rents lead to higher personalism levels. Ample unearned resources allow rulers to finance patronage networks and reduce the need to share power (Chehabi and Linz Reference Chehabi and Linz1998; Meng Reference Meng2020). Although not focusing directly on personalization, some suggest the influence of foreign countries promotes power consolidation. Soviet sponsorship facilitated the adoption of coup prevention strategies (Casey Reference Casey2020), while defence alliances make elite purges more likely as dictators anticipate military support (Boutton Reference Boutton2019; Decalo Reference Decalo1989).

The works above leave three important points unaddressed. First, many critical steps toward power concentration are often highly visible and are unlikely to go unnoticed, so the conditions under which such moves can be made need further investigation. Second, at the empirical and conceptual level, many prior studies did not focus on (or measure) personalism directly but on partial reforms and other outcomes. Finally, by examining the impact of structural or time-invariant factors, prior studies can inform us about cross-country differences in levels of personalism emerging from distinct conditions, but less about surges during the tenure of a given leader. This leaves unexplored the timing of power concentration and, particularly, how intra-elite interactions and opportunity structures can be transformed so that surges in personalism can occur. Noticeable changes in the organization of autocracies normally take place when a shock, such as an irregular intervention, alters the underlying balance of power. Indeed, regime or leader changes are key observable outcomes of ‘successful’ coups. The direction of those changes has sparked an intense scholarly debate about the impacts of coups in autocracies and their potential democratizing effects (Derpanopoulos et al. Reference Derpanopoulos2016; Derpanopoulos et al. Reference Derpanopoulos2017; Miller Reference Miller2016; Thyne and Powell Reference Thyne and Powell2016; Varol Reference Varol2017).Footnote 3 Others find that coups are followed by significant increases in repression (Curtice and Arnon Reference Curtice and Arnon2020; Lachapelle Reference Lachapelle2020).

This literature has almost exclusively centred on the consequences of successful coups. Failed coups, constituting half of all coup attempts, did not receive scholarly attention until recently. Using individual data on cabinet members in autocracies, Bokobza et al. (Reference Bokobza2022) find that failed coups lead to cabinet purges, especially of higher-ranking members and those holding strategic positions. Country-level evidence also shows that coup-surviving rulers are likely to rely on purges (Easton and Siverson Reference Easton and Siverson2018). Similarly, scholars have found that failed coups are followed by higher levels of both violent and low-intensity repression (Curtice and Arnon Reference Curtice and Arnon2020; Oztig and Donduran Reference Oztig and Donduran2020). However, a post-coup increase in repression, or the leaders' tenure, may also be a by-product of other underlying, more profound changes in the organization of a regime. In fact, as Frantz et al. (Reference Frantz2019) show, personalization in dictatorships leads to more violent repression. So the documented long-lasting effects on repression or survival might be in part explained by increased personalism levels brought about by a failed coup. Furthermore, although a logical immediate response, purges are just a partial, momentary tactic, which cannot solidify a dictator's power in the long-term, as some studies posit, unless accompanied by other measures. Extensive purges can alienate remaining elites and spur retaliation, do not guarantee their long-term loyalty, and may leave some co-conspirators undetected and unpunished (Easton and Siverson Reference Easton and Siverson2018; Sudduth Reference Sudduth2017; Thyne and Powell Reference Thyne and Powell2016; Woldense Reference Woldense2022).

Although most of the ‘good coup’ debate focuses on successful coups, Thyne and Powell (Reference Thyne and Powell2016) notably found that failed attempts may also promote democratization as coup-surviving leaders may be prompted to share power to remain in office. Post-coup liberalization, they aver, removes ‘the underlying conditions that precipitated the coup’ and may enable leaders to reap the benefits of a strengthened economy, political legitimacy, and foreign relations (Thyne and Powell Reference Thyne and Powell2016, 199). Their focus, however, is on regime transitions (rare events) not on changes of a continuous, underlying trait within an autocratic spell. Furthermore, a qualitative re-evaluation of cases in Africa suggests that the positive effect of failed coups on democratization may be due to false positives in cross-national data. Failed coups may bolster a state's pre-coup political trajectory, spurring democratization in some contexts or further autocratization in others (Powell, Chacha, and Smith Reference Powell, Chacha and Smith2018, 240).Footnote 4

The Argument: Why Leaders Personalize After Failed Coups

Rather than spurring democratic reforms, we contend that failed coups in dictatorships are much more typically followed by personalization. Power relations between the dictator and the ruling coalition are zero-sum, making intra-regime bargains potentially conflictual (Geddes, Wright, and Frantz Reference Geddes, Wright and Frantz2018; Roessler Reference Roessler2011; Svolik Reference Svolik2012). Any increase in the dictator's power risks aggrieving elite members. Specifically, ‘[w]hen the members of the ruling coalition suspect that the dictator is making steps toward strengthening his position at their expense, they may stage a coup d’état in order to stop him’ (Svolik Reference Svolik2009, 479). Certain shocks can alter such bargains and cause the balance of power to favour the autocrat and reduce temporarily the credibility of that threat. Particularly, failed coups uncover four types of information that create incentives and opportunities for dictators to usurp power. First, failed coups inform leaders about the existence of internal threats, motivating them to adopt measures to secure their survival. Second, failed coups inform the ruler about the elites' loyalty and expose opposing factions. Third, failed coups inform the elites about the existence of a risk of exclusion – encouraging them to back the ruler's protective reforms. Finally, under certain circumstances, failed coups can reveal information about the dictator's strength, which impels the elites to reconsider challenging his position.

Incentives

Failed coups are eye-opening shocks from inside the regime that signal to dictators that their position is insufficiently entrenched and that the existing arrangements guiding the relationship with the support coalition are not effective in deterring elite rebellions. In Easton and Siverson's (Reference Easton and Siverson2018) words, ‘[a] coup attempt is visible evidence that people close to the leader have made an estimate that the leader is weak enough to be removed by the use of force and/or they are dissatisfied enough with the status quo that an attempt is worthwhile’. Leaders are, therefore, prompted to take action to eradicate further challenges and, hence, are not only able to cling to power but also avoid the typical post-exit consequences of being ousted forcefully – namely, execution, prison, or exile (Escribà-Folch Reference Escribà-Folch2013; Goemans Reference Goemans2008).

Some suggest that dictators will often respond to coup attempts or threats by adopting liberalizing reforms (Thyne and Powell Reference Thyne and Powell2016) or by making concessions in the form of institutionalized power sharing (Boix and Svolik Reference Boix and Svolik2013). Such tactics, however, do not address the ‘underlying conditions’ that make coups possible. Redistributing power enhances insiders' (and even outsiders') ability to coordinate against the ruler, which would render the elites' promise not to stage a coup in the future incredible while constraining the ruler's future ability to protect himself. As Meng (Reference Meng2020, 4) puts it, ‘[i]nstitutions that empower and identify specific challengers help to solve elite coordination problems, therefore better allowing them to hold incumbents accountable’.Footnote 5

Failed coups should thus encourage dictators to capitalize on their (temporary) advantage and lock in reforms that consolidate their position in the long term and effectively prevent insiders from staging another coup in the future. Rather than empowering elites, personalization seeks to reduce elites' incentives to act against the dictator and, importantly, to undermine their ability to do so. Therefore, while we agree with Thyne and Powell (Reference Thyne and Powell2016) that failed coups urge leaders to enact ‘meaningful political reforms’, we disagree on the form and direction of those reforms. Such direction is influenced by the unique opportunities a failed coup opens for dictators.

Opportunities

Personalization does not result from increased incentives alone. Post-coup environments also create the necessary opportunities to expand executive power. As said, personalism involves gaining personal control over the security apparatus and the party executive, and over appointments to high office, as well as installing loyalists while purging other officers (Geddes, Wright, and Frantz Reference Geddes, Wright and Frantz2018). Many such moves cannot be subtle or kept secret so, in normal times, usurping power is likely to trigger a backlash (Sudduth Reference Sudduth2017).Footnote 6 As said, the credible threat of a coup is the ultimate instrument elites have to prevent the dictator from sidelining them. If that threat is realized but fails, such credibility is temporarily undermined, which allows leaders to adopt measures aimed at transforming this temporary advantage over the support coalition into a more permanent one. We thus concur with Sudduth (Reference Sudduth2017: 1769) who argue that autocrats' attempts at undermining the elites' capability are more likely ‘when the probability that elites can successfully remove the dictator via coup is temporarily low’. For Sudduth, this advantage stems from taking over in a successful coup. In her argument, heading a coup allows the new ruler to convey information to potential rival groups about the strength and loyalty of his allies (Sudduth and Bell Reference Sudduth and Bell2018). Surviving a coup, we posit, also discloses helpful information and reshapes the dynamics between the dictator and two sets of groups: Those involved in the coup and those who were not. The failure thus creates opportunities for personalization to surge because it weakens elites' ability and willingness to strike again.

First, while informational incompleteness is paramount before (and even during) a coup (Little Reference Little2017; Singh Reference Singh2014), it decreases after an attempt in ways that undermine the inside opponents' capacity to launch another attack. The attempt puts the dictator on full alert, which hinders any potential new plots and, especially, the element of surprise that coups require due to a higher risk of detection. But most importantly, while screening for loyalty can be difficult in political environments where there is a lack of transparency in elite interactions, the use of material inducements to buy loyalty and the use of repression to mute discontent create monitoring costs and impede observing the elites' real preferences and identify challengers (Sudduth and Bell Reference Sudduth and Bell2018; Svolik Reference Svolik2012; Timoneda Reference Timoneda2020); in the aftermath of a failed coup, internal opponents are exposed as coups force high-ranking officials and groups within the ruling coalition to make their preferences public and choose sides.Footnote 7 This improves the dictator's ability to out rivals and opposing factions (Powell, Chacha, and Smith Reference Powell, Chacha and Smith2018) and, in turn, exclude or eliminate them and weaken (if not eradicate) their organizational capacity (Bokobza et al. Reference Bokobza2022; Curtice and Arnon Reference Curtice and Arnon2020; Easton and Siverson Reference Easton and Siverson2018).Footnote 8 Failed coups can lead to more extensive purges of elites who are known (or suspected) to have joined or supported the plot, and can also serve as a pretext to sideline other powerful elites and military units deemed untrustworthy or prone to defect (Bokobza et al. Reference Bokobza2022; Easton and Siverson Reference Easton and Siverson2018).

Second, the new post-coup information environment reshapes the incentive structure of insiders who did not join the attempt. A failed attempt informs elites about the possibility of regime breakdown due to another faction's takeover and, in turn, about the credible risk of losing their privileged inside positions. This mechanism is consistent with a dynamic version of the Geddes, Wright, and Frantz (Reference Geddes, Wright and Frantz2018) argument because, despite failing, a coup attempt may signify a public manifestation of (previously latent or non-existent) factionalism within the ruling coalition. Intra-elite competition and the risk of being replaced by a rival faction induce loyalty to the incumbent dictator from other members of the ruling coalition, who become more likely to acquiesce to personalization since remaining inside the inner circle still leaves them better off than being excluded or risking failure in a new challenge.Footnote 9 Therefore, personalizing measures that safeguard the leader and the regime also protect insiders' positions within the inner circle, although at the cost of diminished influence. Also, the elimination of coup makers' forces leads to the narrowing of the dictator's support coalition. Thus, the loyalty norm increases for remaining backers as the chance of exclusion from a subsequent winning coalition also increases (Bueno De Mesquita et al. Reference Bueno De Mesquita2003).

Finally, under certain circumstances, failed coups can also influence elites' incentives by revealing previously unknown information about the relative strength of the ruler, allowing both actors to update their beliefs downward about the likelihood of success of a new coup attempt (Bokobza et al. Reference Bokobza2022; Sudduth and Bell Reference Sudduth and Bell2018).Footnote 10 The realization that the leader is strong should dissuade elites from challenging him again and pave the way for power accumulation. It is important to note, though, that inferring such strength from a failed putsch may not always be possible unless the outcome is the result of clear military opposition to plotters. The causes of coup failure are oftentimes merely random, circumstantial, or fortuitous ( Kebschull Reference Kebschull1994), so clear information on relative strength is not necessarily disclosed.Footnote 11

In sum, with the opponents' ability to resist decimated and the remaining elites' reduced interest in challenging them, a temporary window of opportunity opens for dictators to accumulate power. Purging foes is one clear measure leaders are most likely to adopt, but effective personalization (and preventing further coups) also makes dictators likely to take further steps. To ensure loyalty, one is gaining personal discretion over the power to appoint and promote high-level officers and officials, which gives leaders control over the composition of their inner circle.Footnote 12 A second one entails putting key institutions that could constrain them under their direct command or creating new (especially recruited) organizations to counterbalance existing ones. In light of this, we therefore hypothesize that ‘personalization in dictatorships will increase sharply after a failed coup’.

Personalizing power is a multifaceted process comprising potentially alternative sequences of manoeuvres. Indeed, the Geddes, Wright, and Frantz (Reference Geddes, Wright and Frantz2018) personalism measure that we employ includes items that capture the extent of the leader's control over the two institutions that could limit his power: The military and the ruling party executive (if one exists). Coups are not only threats hailed from inside the regime but, crucially, in an overwhelming majority of them (over 96 per cent of all attempts since 1946), current active members of the security apparatus were involved (Chin, Carter, and Wright Reference Chin, Carter and Wright2021). It thus seems logical that dictators are more likely to prioritize securing the dependability and control of the agents of repression to ‘coup-proof’ their regimes.Footnote 13 We thus further hypothesize that ‘the effect of failed coups should be stronger on the part of personalization having to do with the security forces rather than the party executive’.

Data and Research Design

To measure failed coups, we use two sources of data. The first is the Powell-Thyne dataset, which records successful and failed coups in 200 countries between 1950 and 2019 (Powell and Thyne Reference Powell and Thyne2011). We also use data on failed coups from the novel Colpus dataset (Chin, Carter, and Wright Reference Chin, Carter and Wright2021), which also includes accompanying historical narratives and data on coup types and characteristics for all countries in the Geddes, Wright, and Frantz (Reference Geddes, Wright and Frantz2018) sample since 1946. The correlation between the two measures in our sample is 0.701. The Powell-Thyne data codes coup attempts against ruling executives, largely aligning with Archigos' list of ‘de facto’ leaders (Goemans, Gleditsch, and Chiozza Reference Goemans, Gleditsch and Chiozza2009). The Colpus dataset, by contrast, is fully compatible with the slightly different list of regime leaders of Wright (Reference Wright2021) as well as Geddes, Wright, and Frantz (Reference Geddes, Wright and Frantz2018), for which we have personalism data.Footnote 14

Our dependent variable is the latent measure of personalism from Wright (Reference Wright2021) and Geddes, Wright, and Frantz (Reference Geddes, Wright and Frantz2018), who derived continuous scores from an item-response theory model based on eight observable indicators. The first four indicators capture personalism in the security forces: (1) personal control over the security apparatus, (2) the creation of a paramilitary group or presidential guard loyal only to the dictator, (3) promotions of officers based on loyalty (from the leader's ethnic, tribal, regional, or partisan group), and (4) extrajudicial arrests and killings of officers from other groups (purges). The last four indicators capture personalism in the party executive: (5) exclusive personal control over appointments to high office, (6) whether the dictator has created a support party, (7) exclusive power to choose the support party's executive committee, and (8) whether the party's executive committee is absent or rubber stamps policy decisions. The decision to include these measures is informed theoretically and validated through factor analysis. The resulting score ranges between 0 (no personalism) and 1 (maximal personalism).

We take advantage of the fact that data on failed coups is available at a monthly level so allowing us to expand our personalism data from yearly to monthly values,Footnote 15 though our results will still hold if we keep all data at the yearly level.Footnote 16 In our initial descriptive quantitative tests, the main explanatory variable is ‘Failed Coup’, which is coded as 0 for all those group-month observations that have not experienced a failed coup before, and 1 for all observations after a failed coup.Footnote 17 If more than one failed coup occurs, our main model also codes these observations as 1. The final sample consists of 139 failed coups.

We run two separate sets of tests to probe our main hypothesis. The first set of models (Table 1) restricts the data to the three years before and after a failed coup only. This provides a direct test of our hypothesis; namely, that personalism levels should increase rapidly after a failed coup. For this first set of models, we run five different specifications using each failed coup variable separately (for a total of ten models). We first run a naive model to ensure that results are not spuriously generated by a model specification. Second, we run the main model with all controls plus leader spell fixed effects. Third, we add leader spells that suffered a successful coup to the sample, since there is a positive probability that the coup could have failed due to the randomness of coup outcomes (Lachapelle Reference Lachapelle2020).Footnote 18 The final two models add regime and country fixed effects, respectively, instead of leader spell fixed effects.

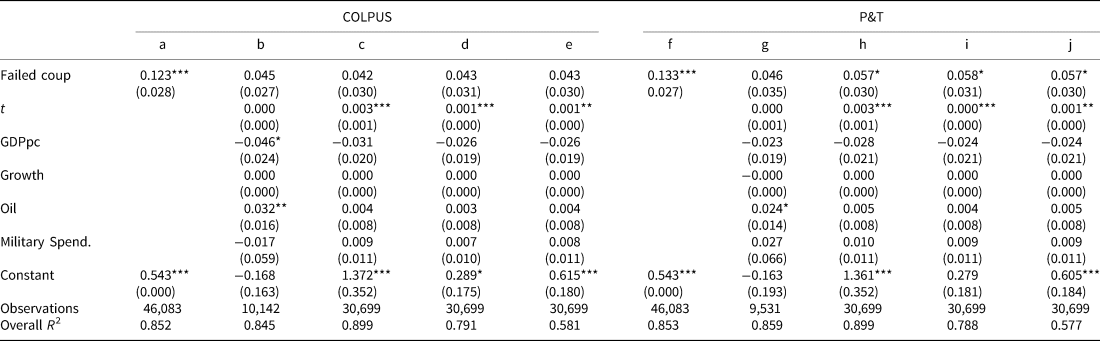

Table 1. Immediate effect of failed coups on latent personalization (DV) using COLPUS (left) and P&T (right), the two measures of failed coups available in the literature

All models show OLS regression estimates with leader spell fixed effects. Models (a) and (f) are naïve specifications, (b) and (g) add controls, (c) and (h) also include regimes that suffered a successful coup, models (d) and (i) use regime fixed effects instead of leader spell fixed effects, and models (e) and (j) use country fixed effects in place of leader spell fixed effects. The sample covers only 3 years before and after a failed coup.

*p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01. Clustered standard errors in parentheses.

The second set of models (Table 2) uses the full sample and thus provides a general view of the long-run effects of failed coups on personalism. We expect that the short-term effects in the first set of models should be much stronger than the long-run effects, but both should be positive. We also run five different specifications using both Colpus and P&T. The first model is again a simple bivariate specification. The second restricts the sample to only leader spells that experienced at least one failed coup. The third model uses the full sample, including cases that experienced a failed coup, a successful coup, and no coup at all. The last two models again replace leader spell fixed effects with regime and country fixed effects, respectively.

Table 2. Long-term effect of failed coups on latent personalization (DV) using COLPUS (left) and P&T (right), the two measures of failed coups available in the literature

All models show OLS regression estimates with leader spell and year fixed effects. Models (a) and (f) are naïve specifications, (b) and (g) add controls, (c) and (h) also include regimes that suffered a successful coup, models (d) and (i) use regime fixed effects instead of leader spell fixed effects, and models (e) and (j) use country fixed effects in place of leader spell fixed effects. These models include the full sample.

*p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01. Clustered standard errors in parentheses.

As for our second hypothesis, we construct additional latent variables to capture party executive personalization and personalization of the security forces. We use the four constituent measures of party personalism to create our latent party personalism score and the four constituent measures of personalism in the security forces to create our latent score for security forces personalism. Lastly, to ensure that purges are not driving the results, we create a separate latent variable for personalism in the security forces without the constituent variable for military purges. These results are presented in Table 3 below, with the expectation that the impact of the failed coups will be stronger for the personalization of the security apparatus rather than the party executive.

Table 3. Immediate effect of a failed coup on the different dimensions of personalism (Hypothesis 2), using COLPUS (left) and P&T (right), the two measures of failed coups available in the literature

All models show OLS regression estimates with leader spell and year fixed effects. The sample covers three years before and after a failed coup.

*p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01. Clustered standard errors in parentheses.

Regarding control variables, our models include military spending (Easton and Siverson Reference Easton and Siverson2018), oil income (Fails Reference Fails2019), GDP per capita, and economic growth.Footnote 19 In models with a longer time horizon (Table 2) we also include a time trend yWiN8GI3, constructed at the group-month level and starting at 1 in the first month a leader spell is observed, increasing sequentially by one unit each month thereafter until the leader exits the dataset. The variable allows us to model changes in predicted personalism over time. Including leader spell fixed effects makes it unnecessary to control for mean levels of personalism before the coup. Since our dependent variable is continuous, our method of choice is a linear OLS model with standard errors clustered by leader spell.

Results: Failed Coups and Personalization

We begin by presenting some descriptive statistics.Footnote 20 The average year-on-year increase in personalism for dictators who do not face a coup attempt in the intervening year is 0.009 (or just under 1 per cent, given that the personalism scale runs from 0 to 1). By contrast, the average year-on-year increase in personalism when a dictator survives a failed coup attempt is 0.06 (6 per cent). In other words, personalism jumps more than six-fold after a failed coup.

The main results are reported in Tables 1 and 2, where the dependent variable is the latent level of personalism in all models. Table 1 shows the results for the ‘immediate’ effect of failed coups on personalism, while the models in Table 2 use the full temporal sample. In both Tables, models (a) through (e) use the Colpus failed coups measure while models (f) through (j) use Powell & Thyne's measure. Standard errors are clustered by leader spell in all models.Footnote 21

The coefficient for the dichotomous failed coups variable in Table 1 is positive and statistically significant in all models, including those with the strictest specifications using leader spell fixed effects – models (b) and (g). The effect also exists in the naive models (a) and (f), which ensures that it is not spuriously created by adding extra parameters.Footnote 22 The coefficients are robust to different model specifications and different samples. Models (b) and (g) provide strong evidence that personalism increases sharply after a failed coup in those leader spells that experience at least one failed coup. Models (c) and (h) confirm that the finding obtains even when leader spells that experienced a successful coup are added to the sample. Lastly, models (d), (e), (i), and (j) show that the model is robust to country and regime fixed effects specifications. As for the control variables, their expected long-run effects do not necessarily apply equally in the short term, which explains some of the variations between the Colpus and P&T measures. Note that models with leader spell fixed effects explain a large amount of the variation in personalism – between 84.3 and 88.7 per cent.

Table 2 reports the results for the full sample of cases and years. The results provide further evidence that failed coups lead to greater levels of personalism, but that the effect is weaker in the long run than in the short term. Besides the naive models, the coefficients are all in the expected direction but all are either close to statistical significance (using COLPUS) or statistically significant only at the 0.1 level (using P&T). The coefficients for the control variables are consistent with our theoretical expectations. The time trend is positive and statistically significant across most models. GDP per capita is negatively associated with increases in personalism. Greater military spending generally leads to more personalism, as do increases in oil income. Lastly, it is worth noting that failed coups (in a model with group fixed effects) explain a large majority of the variation in the model using Colpus data – 73.8 per cent.Footnote 23

To examine how personalization evolves both before a failed coup and after it, we plot the predicted values of personalism by month, for the three years before and after the failed coup. The results are shown in Fig. 1. The plot uses data from Colpus.Footnote 24 The red vertical line represents the month when a failed coup happened and the black line plots the predicted personalism score before and after the failed coup for all the leader spells that experienced at least one event.Footnote 25 The model predicts relatively stable, if slightly declining, levels of personalism before the failed coup, and then a sudden, substantial spike in the period after the failed coup. A majority of the increase takes place in the first two years and stabilizes in year three. More specifically, personalism decreases slightly before a failed coup, from 0.385 three years out to 0.36 one year before. After the failed coup, the increase in personalism is substantial, going from a predicted value of personalism of 0.366 to 0.497 within twenty-four months after the failed coup event. This represents a large, substantively significant increase in personalism of 35.8 per cent in the two years following a failed coup.

Figure 1. Predicted personalism before and after a failed coup (x = 0) based on model (b) from Table 1. Personalism variable scaled between 0 and 1. 95% confidence intervals shown.

Two well-known examples illustrate the model's large predicted increase in personalism. On June 30, 1973, Ahmed Hassan al-Bakr and his deputy Saddam Hussein faced an attempted coup (and an assassination plot) by mostly junior elements within the public security department, led by Col. Nadhim Kazzar (Chin, Wright, and Carter, forthcoming, Reference Chin, Wright and Carter2022, 611–2). After a set of purges and reshuffling, Hussein tightened his grip on the regime, and the predicted level of personalism went from 0.521 before the attempted coup to 0.782 the year after it. The attempted coup led to a 50 per cent increase in personalism in the Iraqi case.Footnote 26 In contrast, another leader who personalized power but did not face an unsuccessful coup attempt, Vladimir Putin, in the 2000s, increased his level of personalism from 0.541 to 0.606, a jump of only 12 per cent over a full decade. Other examples of rapid personalism after a failed coup as predicted by the model were Burma (Myanmar) in 1976 (a 42 per cent increase), Libya under Gaddafi in 1975 (a 62 per cent increase), and Mali in 1978 (a 46 per cent increase). In addition to these examples, we provide three full case studies – Algeria, Sierra Leone, and Benin – to further illustrate the mechanisms of increases in personalism after failed coups.

These results are congruous with our theoretical expectations regarding how dictators operate after failed coups. Failed coups act as a shock, one that allows for the quick restructuring of institutions and personnel practically without backlash.

Table 3 reports the results of our second hypothesis. The evidence strongly supports the idea that rapid increases in personalism are concentrated primarily on the security apparatus, but they are not solely driven by purges. The failed coup coefficients in models (b) and (d), where the dependent variable is a latent measure including all four constituent terms for security personalism, are both substantively and statistically significant at the 0.01 level. When the latent variable is constructed without military purges, the coefficient remains significant at the 0.05 level. It also remains substantively significant, even though the size of the coefficient decreases slightly. Conversely, personalism around civilian institutions is not as strong immediately after a coup, as shown in models (a) and (d). The coefficients in these models are positive but their effect is weaker and not statistically significant at conventional levels. That said, some constituent terms on their own show some evidence of statistical and substantive significance: For example, the control of appointments to high office and the creation of a new party, which serves to counterbalance the military (Tables A1 and A2 in the Appendix).

A Synthetic Control Approach

The quantitative evidence presented above remains largely descriptive. To determine the causal nature of failed coups on increases in personalization, we employ a synthetic control approach. Synthetic controls were introduced to allow researchers to estimate causal relationships in situations where a small number of units experienced a given event or intervention (treatment). By generating a donor pool from similar cases where no treatment occurred, we can estimate the counterfactual response by the treated unit absent the treatment (Abadie and Gardeazabal Reference Abadie and Gardeazabal2003). Synthetic controls use a data-driven process to determine the weights that make the control group closely resemble the treatment group before the treatment occurs. The response by the control group can then be considered as the counterfactual response for the treatment group. Recent work has extended the application of synthetic controls to multiple units. Synthetic controls are useful in comparative case studies because they provide a data-driven formalization of the selection of comparison units and the assignment of weights to each unit in the control group, which is an innovation over difference-in-differences methods (Abadie Reference Abadie2021). In recent years, this approach has become increasingly common in the social sciences, with particularly promising applications in comparative politics (Abadie, Diamond, and Hainmueller Reference Abadie, Diamond and Hainmueller2015).

We provide one such novel application of synthetic controls to failed coups and their effects on personalization. In our sample, twenty-three unique leader spells experienced at least one failed coup that was not preceded or followed by a successful coup within three years. This sampling approach ensures leader continuity. It also allows us to map personalization trajectories before and after a failed coup for a longer period.Footnote 27 We then centre all units in the treatment group at the time when the failed coup took place and use the failed coup as treatment.Footnote 28 We apply a synthetic control to a non-synchronous event, one of the first applications of this kind in the authors' knowledge. We pre-select our control sample to include leader spells that experienced at least one successful coup and no failed coup. Our logic is that there is a certain randomness to coup success (Lachapelle Reference Lachapelle2020; Singh Reference Singh2014), thus units that experience a successful coup have a similar latent probability of experiencing a coup regardless of the outcome. There are thirty-nine such groups, among which the algorithm selects the control sample that most resembles the treatment sample before the failed coup (treatment) and assigns a placebo.Footnote 29

Figure 2 plots the results of the multiple synthetic control.Footnote 30 The solid line represents the evolution of personalism in leader spells that suffered a true failed coup, while the dashed line reflects personalism over time in leader spells that were assigned a placebo failed coup. The trend before the failed coup (vertical line; x-axis = 0) is similar for both groups, with a slight but non-significant positive tendency. The lines then begin to diverge after the failed coup, with the sharpest increase during the first year. Again, the lack of smoothness in the trends is due to the fact that the monthly means for personalism are the averages of the yearly scores across cases. At twelve months ‘after’ the failed coup, the treatment and control groups diverge by 0.06 points in the personalism scale. The average yearly increase in personalism in the sample is 0.009 points, making a large one-time change of 0.06 substantively significant. This matches our descriptive results and confirms the finding in Table 1 that personalism is higher after a failed coup. Moreover, it also shows that failed coups have a strong and ‘immediate’ causal effect on increases in personalization.

Figure 2. Predicted personalism before and after a failed coup attempt, based on the synthetic control model. The personalism variable is scaled between 0 and 1. 95% confidence intervals shown.

To add more evidence to the synthetic control analysis, we provide a more traditional application of synthetic controls to six cases: Sierra Leone under Siaka Stevens, Algeria under Houari Boumédiène, Mathieu Kérékou in Benin, Zia Rahman in Bangladesh, Saddam Hussein in Iraq, and Heydar Aliyev in Azerbaijan. As case studies, we describe the first two cases in depth in the final section of the article. Figure 3 plots the evolution of personalism over time for each of these examples. As noted, the lack of smoothness in the trend is due to the underlying structure of the data. In all three cases, we observe a similar trend between the treated unit and the control group pre-treatment and a sharp divergence post-treatment. Personalism rises the sharpest in Sierra Leone, from 0.25 before the coup to 0.58 afterwards. The yearly personalism data takes a few months to reflect the change, due to the coup occurring in early 1971, with the data only increasing in 1972. In the case study we show how personalization was linked to the failed coup directly.

Figure 3. Synthetic control results for Algeria, Sierra Leone, Bangladesh, Benin, Iraq, and Azerbaijan, based on synthetic control models for each individual case. The personalism variable is scaled between 0 and 1.

Robustness Checks

Four robustness checks are included in the Appendix. First, we confirm in Tables A1 and A2 that purges are not driving the results, thus complementing our evidence from Table 3. Second, in Tables A3 and A4, we replicate the analysis in Tables 1 and 2 using yearly data, and the results are consistent. Third, in Table A6, we explicitly address reverse causality by adding one, two, and three-year lags and leads for our failed coup variable, where we find substantive and statistical significance only in the lagged models. Lastly, to probe our argument further, we conduct two placebo tests using assassination attempts and civil war onsets. Significant increases in personalism after a failed assassination attempt could shed doubt on our argument that failed coups are not a mere pretext but change the information game for the regime's main actors. Similarly, higher levels of personalism after civil war onsets would mean that violent events, not just failed coups, trigger periods of rapid personalization. We find that neither assassination attempts nor civil wars have a strong, positive impact on personalism in the short term (Figures 1 and 2 in the Appendix).Footnote 31

Personalizing After Failed Coups in Algeria, Sierra Leone, and Benin

We now illustrate our arguments by presenting brief case studies of the evolution of personalism surrounding three failed coups in Algeria, Sierra Leone, and Benin.

Algeria-Boumédiène 1967. After ousting Ahmed Ben Bella in a bloodless coup in 1965, Houari Boumédiène, who had been defence minister and vice-president, led an initially collegial ‘collective executive’ called the Council of the Revolution (Naylor Reference Naylor2015). Twenty-two out of twenty-six council members were officers of the Armée Nationale Populaire (ANP), the direct successor to the armed wing of the ruling party, the Front de Libération Nationale (FLN) (Evans and Phillips Reference Evans and Phillips2007). The council was an alliance of two factions. The mujahidin, the old-line wilaya commanders who had led the independence struggle were led by Col. Tahar Zbiri, who took command of the military from Boumédiène after 1965. Then there was the ‘Oujda Group’, led by Boumédiène himself and supported by technocrats in the cabinet and the FLN (Zartman Reference Zartman and Welch1970, 242). As Col. Zbiri, whose support was critical for the 1965 coup's success, gained control over the military, his faction increasingly controlled the Council of the Revolution. To compensate for his increasing weakness, in June 1967 Boumédiène began to make key decisions within his cabinet where he controlled a majority and refused to convene the council where he was outnumbered (New York Times 1967). When Zbiri protested, Boumédiène tried to sideline Zbiri's faction and, on 10 December 1967, reassigned or dismissed five council members, including four wilaya commanders and Col. Zbiri's deputy, Youssef Khatib. Boumédiène also named his close Oudja Group ally, Finance Minister Kaid, to reorganize the FLN (Associated Press 1967). Misjudging his military support, Zbiri launched a coup on 14–15 December 1967 (Quandt Reference Quandt1972). However, the advance of several tank battalions on Algiers was repelled by loyal gendarmerie and air force units, and Boumédiène neutralized political support for the coup by coopting other opposition (Lenze Reference Lenze2016, 29). In the wake of the failed coup, Zbiri and his collaborators were forced into hiding. Zbiri organized several clandestine assassination attempts in hopes of returning to power but fled to Tunisia in June 1968 (Ottaway and Ottaway Reference Ottaway and Ottaway1970, 254–5).

The coup attempt allowed Boumédiène to take ‘complete control over Algeria’ (Naylor Reference Naylor2015, 148). Within days of the attempt, Boumédiène controlled all appointments to high office within the Council of the Revolution, the ANP, and the FLN. First, Zbiri's failed coup ‘gave Boumediène the opportunity to suppress the General Staff altogether’. With the general staff dissolved, ‘the armed forces possessed no institutional expression of their collective interests outside Boumediène's Ministry of Defense’ (Roberts Reference Roberts1984). Boumédiène immediately placed the country's armed forces under his command, ‘assuming personally many staff responsibilities’ (Tartter Reference Tartter and Metz1994, 254). He also tightened his grip on the secret service, the Sécurité Militaire (Evans and Phillips Reference Evans and Phillips2007), which was headed by his head henchman, Lt Col. Kasdi Merbah. Second, Boumédiène ethnically narrowed the regime in Arab hands. He purged several former guerilla leaders, especially Kabyle and Shawiya (Zbiri himself was a Shawiya Berber). After Zbiri's coup attempt, Berber's military power was curtailed (Horowitz Reference Horowitz1985, 517). Finally, Boumédiène ‘excluded ANP leadership from day-to-day policy making but remained close to the army commanders whose support he needed to maintain political control’ (Tartter Reference Tartter and Metz1994, 254). Boumédiène ensured men personally loyal to him commanded key posts in the defence ministry, including the ANP Secretary General, Col. Abdelkader Moulay, and the head of the ANP Political Commissariat, El Hachemi Hadjerès, (Roberts Reference Roberts1984). Many of Boumédiène's favoured remaining elites lacked an independent base of support, ensuring they had neither the incentive nor the capability to challenge him.Footnote 32

The 1967 failed coup, in short, ensured the victory of the Oudja Group in general and Boumédiène in particular and marked the demise of the mujahidin in the regime's inner circle. The Council of the Revolution shrank to only fourteen members by 1970; only eight Council members survived by the time Boumédiène became terminally ill in 1978 (Tartter Reference Tartter and Metz1994, 254). These bold personalization moves are reflected in Wright's (Reference Wright2021) latent personalism score for Algeria under Boumédiène, which stood at 0.427 before the coup and 0.59 afterwards, an increase of 38 per cent.

Sierra Leone – Stevens 1971. Siaka Stevens, leader of the All People's Congress party, had won elections in March 1967 but was prevented from taking office as prime minister due to a veto coup by the then-army commander, Brig. John Lansana. In April 1968, Col. John Bangura, then military attaché in Washington, led the so-called Sergeants' Coup that ousted the post-1967 coup military regime and paved the way for Stevens to finally come to office (Kline Reference Kline and Danopoulos1992, 218–20). In late 1968, Stevens began to recruit 80 per cent of new army recruits from northern ethnic groups, not just from his co-ethnic Limba but also many Temne (Harkness Reference Harkness2018, 119). Bangura was promoted to Brigadier and made Force Commander in May 1969. By 1971, Bangura, an ethnic Temne, had grown uneasy about Steven's apparent desire to ethnicize the regime into a Limba-dominated one-party state. First, Stevens pensioned off Mende officers in 1969 (Harris Reference Harris2014, 64). In September 1970, several Temne ministers left Stevens' cabinet and the APC to found the United Democratic Party (UDP), led by Bangura's close Temne associate, John Karefa-Smart. In October 1970, Stevens banned the UDP and began purging Temne officers (Horowitz Reference Horowitz1985, 478) with the support of Limba soldiers and the allied Yalunka and Koranko; Stevens also began to contract Guinean bodyguards to provide for his protection (Harkness Reference Harkness2018, 120). On 23 March 1971, Major Falawa Jawara led a failed attack on President Siaka Steven's residence. Bangura took over leadership of the coup, urging on troops from the Wilberforce Barracks and announcing the putsch on the radio (Fyle Reference Fyle2006, 14, Vidler Reference Vidler1998, 178–9). The coup attempt, which sought to reverse Stevens' campaign against the UDP and Temne officers very nearly succeeded (Harris Reference Harris2014, 64). ‘With Stevens in hiding, the military split into factions with Creole and Limba soldiers refusing to follow the northern coup leaders’ orders’ (Harkness Reference Harkness2018, 120). However, after the army's third-in-command, Lt. Col. Sam King, publicly broadcast a denunciation of the coup, other senior officers turned on Bangura and arrested him (Associated Press 1971), and Stevens emerged from hiding.

With this new information, Stevens took immediate action to secure his rule after the failed coup. Having lost faith in the loyalty of his military, Stevens rushed to neutralize internal army opposition. First, he struck a defence pact with Guinean President, Sekou Touré, on March 26 to consolidate his control. Two days later, the first of 200 to 300 Guinean troops arrived in Sierra Leone to protect him (Hughes Reference Hughes, Macadam, Grindrod and Boas1971). Stevens compensated the remaining loyal soldiers with some 40,000 leones (Sierra Leone's currency) to convince them ‘not only to accept this influx of foreign troops, but to allow their own disarmament’ (Harkness Reference Harkness2018, 121). Second, Stevens accelerated the ethnic narrowing of the regime, ensuring state, party, and army leaders were all Limba. Temne were purged from the army officer corps (Horowitz Reference Horowitz1985, 478). Bangura was tried and executed for treason in June 1971 (Fyle Reference Fyle2006, 14). Stevens installed Colonel Joseph S. Momoh, a 34-year-old fellow Limba, as army head (Harris Reference Harris2014). During the coup attempt, Momoh, a political outsider, had proved his loyalty by providing intelligence to Stevens (Luke Reference Luke1988, 76). Finally, Stevens counter-balanced the army by creating the Internal Security Unit (ISU). He first proposed a paramilitary force on April 4, only eleven days after the failed coup, as a cost-saving measure. He claimed the government could not afford a large army (Kaplan Reference Kaplan1976). In the following months, Cuban, British, and Israeli instructors trained ISU units (Krogstad Reference Krogstad2012). The ISU became Stevens' executive police force, using it to repress, gather information, and ensure favourable election results. The ISU helped the APC win 84 out of 85 contested seats in the 1973 election (Reno Reference Reno and Rotberg2003, 80). Col. Momoh did not object to the new ISU, due to his personal loyalty and his knowledge that other senior officers supported Stevens – the failed coup had revealed their preferences.

In addition to personalizing the security forces, Stevens made institutional moves that ushered in an era of ‘virtually personal rule’ (Fyle Reference Fyle1994, 128). He had parliament rubber stamp a new republican constitution in mid-April 1971, and then promptly amended it to create an executive presidency giving him more power over political and military appointments (Clapham Reference Clapham1972; Luke Reference Luke1988). Two aspects of the new constitution are noteworthy. First, a new republican constitution had been debated for some time since Albert Margai (Sierra Leone's second prime minister) had introduced a draft during his 1964–67 tenure. Yet right after the 1971 coup attempt, Stevens saw a political opportunity to enact it, as factionalism within the government and the army was reduced (Clapham Reference Clapham1972). Second, he made key modifications, among them his personal designation as executive president, a position that was not considered in the original. In all, Stevens eliminated powerful opposition members, personalized and ethnically narrowed the military, enacted a constitution that gave him full political powers, and created a parallel military force – all within one month of the failed coup. Wright's data show personalism under Stevens rose from 0.251 before the coup to 0.585 after, a 133 per cent increase. These personalizing moves succeeded in bringing an end to the cycle of coups and counter-coups since 1967. Stevens retired in 1985 in favour of his hand-picked successor, Momoh.

Benin-Kérékou 1975. In October 1972, a military coup by a quartet of southern (Fon) junior officers ousted the civilian government of Justin Ahomadégbé and installed a military junta led by Major Mathieu Kérékou, a northerner (Somba), who had been the army deputy chief-of-staff. The army's senior officers (mostly southerners) were purged (Houngnikpo and Decalo Reference Houngnikpo and Decalo2013, 7, 102). In the new junta, cabinet portfolios were initially divided between junior officers with ‘some attempt at regional representation . . . Key appointments were Captains Michel Aikpe (minister of interior and security) and Janvier Assogba (minister of civil service), both young militant Fon from the Abomey region’ (Decalo Reference Decalo1973, 477). On 21 January 1975, Captain Assogba, calling Kérékou corrupt, led part of the key Quidah para-commando armed division in a ‘murky and ill-prepared assault’ that ultimately failed (Houngnikpo and Decalo Reference Houngnikpo and Decalo2013, 121).

In the wake of the failed coup, Assogba was imprisoned, seven plotters were sentenced to death, and a further five were given life sentences in March 1975 (United Press International 1975). Kérékou seized the opportunity to personalize the regime and transform the country. He first removed remaining potential rivals within the junta. In June 1975, Kérékou purged Major Aikpe, the popular and powerful minister of interior, who was shot on the pretext that he had been caught having an affair with Kérékou's wife, though in reality Kérékou was concerned that Aikpe's faction of militant officers posed a continuing coup threat (Martin Reference Martin1985, 70). In November 1975, a new constitution was adopted, Dahomey was renamed Benin, and a new support party, the Parti Revolutionnaire du Peuple Beninois (PRPB), became the country's sole legal party (Wilton-Marshall and Shaw Reference Wilton-Marshall, Shaw, Hodson, Hoffman and Bose1975). Kérékou became head of the six-man PRPB politburo, whose next most powerful figures were military officers, Major Michel Alladaye and Lt. Martin Azonhiho (Decalo Reference Decalo and Szajkowski1981, 94–5), who strengthened their positions by demonstrating loyalty to Kérékou by suppressing the general strike and student protests that broke out following Aikpe's murder in the summer of 1975 (Martin Reference Martin1985, 75).

In addition to tightening his control over civilian institutions, Kérékou ‘took overall command of the armed forces and militia’ (Allen Reference Allen1992, 44). He first moved to neutralize the Fon threat in the regular army. In 1975, senior officers from the older Fon generation were purged (Martin Reference Martin1985, 75). Meanwhile, more northerners were promoted to the officer corps and new paramilitary organizations were created (Morency-Laflamme Reference Morency-Laflamme2018, 9).Footnote 33 In addition, Kérékou built up a previously small, ceremonial Fulani-dominated bataillon de la garde présidentielle. ‘Trained by North Korea and with the best weapons in the country, it became the true military prop of the regime against domestic foes and mutinies from within the army’ (Houngnikpo and Decalo Reference Houngnikpo and Decalo2013, 57). The army was reformed to recruit police, gendarmerie, and forestry officers into a ‘People's Revolutionary Army’. By early 1976, the new army was tasked with training a new people's militia (Akindes Reference Akindes, Rupiya, Moyo and Laugesen2015, 50). As measured by the Wright data, the level of personalism under Kérékou nearly tripled, from only 0.23 on the eve of the Assogba coup attempt to 0.65 by the end of 1975. The failed coup thus facilitated Kérékou's domination of an increasingly Marxist single-party regime that would rule until the end of the Cold War.

Conclusion

Despite the global decline in their incidence after the end of the Cold War, coups are still a persistent feature in the politics of the Global South. In fact, 2021 has seen a spike in the number of instances, with seven attempts as of November. Such disruptive, irregular events draw much international attention, typically when they succeed in upending elected, civilian governments. This article shows that coups in dictatorships can have negative, long-lasting consequences even when they fail. In particular, a failed coup creates both incentives and opportunities for the dictator to personalize power by revealing crucial information to both the regime leader and regime elites. Our empirical results confirm the main hypothesis: Failed coups lead to surges in personalism levels in dictatorships, especially those concerning the control of the security apparatus.

This evidence contributes to several strands of literature on comparative authoritarianism and contentious politics. First, we contribute to the growing literature on the consequences of coups. In contrast to the view that failed coups often spur democratization in dictatorships, we find that an opposite trajectory consisting of power concentration takes place more often than not. Second, we further our understanding of the emergence of personalist rule. Failed coups can be seen as early warnings of personalistic rule. Our findings also point researchers in these areas to new research questions; for example, about what other shocks may promote or hinder personalization. We found no evidence that failed assassination attempts or civil war onsets promote personalization, although it is possible that other events other than coups may create ‘critical junctures’ in the life of autocratic regimes.

Supplementary Material

Online appendices are available at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123422000655.

Data Availability Statement

Replication data for this article can be found in Harvard Dataverse at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/NJFAQV.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Milan Svolik, Joseph Wright, the participants at Purdue University's Political Science Research Workshop (November 2020), and three anonymous reviewers for their valuable feedback on previous versions of the paper.

Financial Support

None

Conflicts of Interest

None.