Research on public opinion and voting behavior has frequently shown that the average citizen’s overall level of information, knowledge and understanding of politics is relatively poor. Political knowledge also appears to be unevenly distributed. Of all the many sources of knowledge inequalities identified in the literature (such as resource based, motivation based and race based), this article deals with perhaps the most puzzling: gender differences in political knowledge.

Such differences have proven to be remarkably persistent. Notwithstanding the tremendous increase in the degree of gender equality in political power and resources in industrialized democracies, women appear to know about and participate less in politics than men.Footnote 1 Although some researchers have noted that the difference is often small in comparison to other inequalities such as education or social class,Footnote 2 gender differences in knowledge not only affect more than half the world’s population; they also appear to be the most enduring and strong. The uneven distribution of political knowledge between men and women raises a number of normative concerns. Political knowledge translates into political power: governments are more responsive to citizens’ demands when political knowledge is evenly distributed across social groups.Footnote 3 Moreover, governments have more incentives to be responsive when they can be held accountable, but citizens can only hold governments accountable for their actions when they know what the governments are actually doing. Consequently, if women systematically have less political knowledge than men, they may be less well represented in the democratic system. This would imply a clear disadvantage in women’s capacity to voice their political needs and wants, and to influence the political decision-making process. In short, gender constitutes a long-term dimension of political under-representation, and thus merits the attention of researchers.

Gender differences in knowledge are particularly worthy of attention in Latin America, where women have been historically excluded from political power and participation. In spite of very fast changes over the past decade, there are still very large variations in levels of women’s presence and empowerment across countries in the region.Footnote 4 While the gender gap in knowledge is well documented in advanced industrial democracies such as the United States, Canada and Western Europe, we know very little about the extent of the gender gap in knowledge (and its potential determinants) in Latin America.Footnote 5 If such a gap persists in countries where the degree of gender equality in political power and resources is higher, what should be expected from young or re-emerging democracies facing socio-economic challenges? The political histories of Latin American countries are plagued with many examples of political exclusion, persecution and repression of women’s full equality of citizenship, together with very traditional female-unfriendly economic institutions. Does this additional disadvantage translate into high levels of gender inequality in political knowledge? Or have recent increasing opportunities for women to participate in the political sphere in these countries helped close the gender gap in knowledge?

Common explanations of gender inequality in political knowledge point to traditional social norms that identify women as responsible for parenting and other caring activities, as well as to the disadvantages suffered by women, such as lower levels of socio-economic and cognitive resources.Footnote 6 However, these studies focus only on explanations at the individual level. By contrast, this article tests contextual explanations of the gender gap in knowledge while controlling for the traditional accounts at the individual level. We suggest that the gender gap in knowledge may also be affected by political and economic settings through two interrelated mechanisms: gender accessibility (that is, the extent of available opportunities for women to influence the political agenda) and gender-bias signaling (that is, the extent to which women play important roles in the public sphere).

Confirming previous studies, our findings show that the gender gap in knowledge is smaller among highly educated citizens, in rural areas (where both men and women know little about politics) and in bigger cities (where women’s levels of political knowledge are higher). More importantly, the findings also show that the gap is significantly larger in countries that marginalize the role of women in the public sphere, and smaller where women’s issues are featured more prominently on the political agenda.

Individual and Contextual Determinants of the Gender Gap in Knowledge

Gender differences in political knowledge might arise from three causes: sex differences in resources, differential effects of the antecedents of knowledge for men and women, and differential contexts. To begin with, males and females have differential access to the main antecedents of knowledge (abilities, resources and opportunities). For example, a lack of educational opportunities might reduce women’s aggregate levels of knowledge compared to men. Secondly, men and women may respond differently to the same factors; education may provide more returns for women than for men, or vice versa. Thirdly, gender differentials may reflect broader cultural/economic/political contexts. For instance, Inglehart and Norris argue that women’s involvement in politics is discouraged in societies where traditional sex roles are dominant (such as agrarian societies).Footnote 7

As Desposato and Norrander have pointed out,Footnote 8 contextual effects cannot be measured in single-country studies. Instead, we need a multi-country, two-level interactive model in which knowledge may vary as a function of individual factors, as an interaction of such factors and gender, and as a function of the interaction of context and gender. If only individual variables predict the level of knowledge, then the gender gap is caused by unequal access to resources and opportunities between men and women (such as education, income, time). If individual factors interact with gender, then the gender gap reflects an inequality in the magnitude of the effects of each of the antecedents of knowledge for men and women. For example, poverty or lack of time might dampen women’s knowledge more than men’s, and education might promote women’s knowledge more than men. Finally, if the gender gap varies across countries, then it might also depend on some contextual variables. Our study includes a diverse set of countries, which allows us to test for each type of mechanism.

At the individual level, previous research has identified numerous factors that contribute to explaining the gender gap in knowledge. Traditional explanations are based on socialization theory, which states that conventional social norms define men as citizens who are in charge of public life and women as being in charge of the domestic or private domain, as they are seen as more committed to childrearing, caring and family life more generally.Footnote 9 These responsibilities involve an additional cost in the decision to become informed about politics. Part of this same argument is that men and women are situated differently in the social structure and have different levels of material and cognitive resources, distinct burdens of work and responsibilities, and consequently different amounts of time available to dedicate to becoming informed about politics.Footnote 10

An additional explanation for the gender differences in knowledge is based on the possibility that the determinants of what people know or ignore about politics (that is, abilities, resources and motivation) are themselves gendered. Women are less likely than men to possess the precursors of knowledge. But when they attain a greater level of resources (such as education or income), they might be especially encouraged and therefore receive significantly larger returns on their political knowledge than their male counterparts. Some studies argue that even when the socio-economic differences between men and women are slight (or even disappear), their effect on what people know or ignore about politics might be different for men and women. In particular, evidence from the United States demonstrates that the positive effect of education on knowledge is lower for women than for men.Footnote 11 By contrast, a recent study of twenty-seven European countries shows that the magnitude of the effect of education on political knowledge is higher for women than for their male counterparts.Footnote 12

In addition, some studies have speculated that the gender gap in political interest and knowledge could disappear over time due to changes in socialization and generational replacement.Footnote 13 Previous generations were socialized under (either democratic or undemocratic) political systems in which women were explicitly or implicitly excluded from politics and the labor market. As a consequence, the gender gap is argued to be greater for older citizens than for their younger counterparts.

However, these individual-level explanations account for only one part of the gender disparity. An alternative approach to explaining the enduring gender gap in knowledge is to take societal contextual factors into account. This is what we do in this article: focus on contextual factors while controlling for the individual-level factors previously used in the literature, discussed above. Knowledge gender gaps have rarely been discussed in a cross-national context (with the sole exception of Kittilson and Schwindt-Bayer).Footnote 14 In fact, only studies focusing on gender differences in political participation and attitudes have adopted this strategy.Footnote 15

Here, we suggest that there are at least two mechanisms through which the contextual setting may influence gender differences in political knowledge. The first of these mechanisms is gender-bias signaling. We argue that settings that send strong signals that women only play a marginal role in the public sphere (gender bias) may discourage women’s interest in (and access to) political information relative to men’s. So, for example, perceiving that most women tend to play a relatively unimportant position in the labor market, or that politics is mainly a men’s game, may cause women to pay less attention to political issues than men.

The second mechanism, gender accessibility, operates by creating the conditions for female participation in politics. Women tend to be one of the most disadvantaged groups in terms of political capital. Therefore, contexts that facilitate their political participation and the introduction of female-related issues into the political agenda should also help foster their interest, thereby reducing the gender gap in knowledge.

Previous studies about the influence of contextual factors on the gender gap in political engagement have claimed that elected women constitute symbols of inclusion in the political system. Thus, their presence in political institutions incentivizes the women (especially young women) to get involved in politics and to be exposed to political information, thereby raising their knowledge of politics.Footnote 16 The logic behind this argument is linked to the idea of descriptive representation, which refers to the similarity (in terms of race, social class or, in this case, gender) between representatives and citizens.Footnote 17 According to this approach, increases in the descriptive representation of particular groups become especially relevant when those groups (in this case, women) have been historically excluded from politics.Footnote 18 The descriptive representation of women may also facilitate the defense of women’s interests that are best defended by women themselves, therefore increasing substantive representation as well.Footnote 19 We contend that greater representation of women in political institutions can be interpreted as a signal that politics is not only a men’s game, which could help reduce the gender gap in knowledge. Therefore, we consider this factor to be an indicator of gender-bias signaling in the political dimension.

Findings in the literature regarding the effects of descriptive representation are mixed, with a clear predominance of studies focusing on the United States. Some of them find that females living in US states with women in charge of prominent political offices are significantly more likely to be politically informed, interested and involved.Footnote 20 However, others have found little support for the role of women’s descriptive representation in encouraging political engagement.Footnote 21 Studies seeking to explore the link between women’s representation and political engagement (and/or attitudes) across countries also offer mixed evidence. Whereas some scholars find support for the descriptive representation hypothesis in Latin America,Footnote 22 EuropeFootnote 23 and Sub-Saharan Africa,Footnote 24 other studies that have analyzed a wider geographical areaFootnote 25 find little support for this hypothesis.Footnote 26

It appears, then, that the inconclusive findings of this literature call for additional tests. This is what we do here, but we account for gender-bias signaling in both the political and socio-economic dimensions. Although it has been ignored in the previous literature, we argue that the degree of male predominance in the labor market is a relevant economic dimension of gender-bias signaling. Contexts in which women earn a fraction of men’s income may further the idea that females’ role in the public sphere is only secondary to (and less important than) their traditionally pre-eminent role in the private sphere. On the contrary, gender income equality may foster women’s interest in public and political issues and, therefore, help reduce the gender gap in knowledge. The gender gap in earnings is acute in Latin America, and differences between countries have grown very visibly during the 2000s, with declines in twelve countries and increases in another six.Footnote 27

Moving on to the second mechanism, gender accessibility, previous studies have shown that institutions influence citizens’ political behavior and opinions through a psychological mechanism.Footnote 28 Institutions are symbols that represent ideals of how democracy works, and provide cues for citizens about such ideals. Thus citizens learn more about political institutions with each involvement in politics. And what they learn in turn shapes their political attitudes, opinion and behaviors.Footnote 29 Kittilson and Schwindt-Bayer)Footnote 30 have shown that gender differences in political engagement tend to be smaller in more proportional electoral systems, arguably because proportionality opens the political structure up to the representation and inclusion of diverse social groups that tend to be under-represented in majoritarian systems. This may help introduce alternative issues into the political agenda and encourage women to engage in politics.

Other power-sharing institutions such as federalism may have similar effects, as they multiply access points for citizens to interact with institutional politics and gather political information.Footnote 31 Previous studies have found that women tend to know more about local issues.Footnote 32 Moreover, there is evidence that when looking at citizens’ knowledge of local rather than national politics, the gender gap vanishes or even reverses.Footnote 33

Although previously overlooked in the literature, we contend that there is an additional and equally important factor that refers to the accessibility of the political context: the institutionalization of the party system. There are at least two mechanisms through which stable party systems may facilitate women’s access to politics. On the one hand, stability is needed in order to form stronger links with parties,Footnote 34 which might potentially be more beneficial for those, like women, who have traditionally less access to politics. Parties are primary vehicles of political information,Footnote 35 and thus contexts of party system stability may help foster women’s political knowledge. On the other hand, stability may also give women better access to politics and the political agenda. Unstable, weakly institutionalized party systems in Latin America are characterized by competition based on personal appeals and short-term populist policies;Footnote 36 female-friendly policies and discourses are completely dependent on the will of charismatic leaders.Footnote 37 Several studies have found that weak institutionalization provides a poor environment for women’s engagement in politics. Weakly institutionalized parties tend to be biased toward members with strong political capital and external support, which are resources that women (compared to men) tend to lack.Footnote 38 Studies also indicate that female activists’ influence is stronger in more stable, institutionalized parties, where the rules of the game are clear and widely known to all and there is less need to rely on the ‘boys’ networks’ in order to gain access to the agenda.Footnote 39 Arguably, women’s achievements will be more likely to have an impact on women’s political engagement where there is greater institutionalization.

There is huge variation in the degree of institutionalization of political parties across Latin America. However, there is a tendency to find relatively unstable, personalistic and informal party systems in many countries. This context does not seem to be the best place for women to engage with party politics and to influence the political agenda, which might result in lower levels of political information. In short, we contend that, apart from power-sharing institutions, there is an additional key factor regarding the accessibility of the political context: party system institutionalization. And this needs to be considered when explaining the gender gap in political knowledge.

To recapitulate, we test the extent to which certain contextual factors contribute to increasing or decreasing the gender gap in political knowledge in Latin American countries, while controlling for the typical antecedents of knowledge at the individual level. We suggest that there are two mechanisms through which the contextual setting may influence the size of the difference in knowledge between men and women: gender-bias signaling and gender accessibility. We test the extent to which these mechanisms operate in Latin America while controlling for other contextual factors that have been considered by previous studies: the degree of political freedomFootnote 40 and socio-economic development.Footnote 41

Research Design: Data and Variables

One reason explaining the lack of attention given to context in relation to the gender gap in knowledge might be connected to the scarcity of data. There is indeed little comparative data containing enough information to construct valid indexes of political knowledge that are comparable across countries.Footnote 42 In this respect, the 2008 Americas Barometer offers a unique opportunity to use a comparable set of measures about citizens’ political knowledge across countries.Footnote 43 Accordingly, we use data from eighteen Latin American democracies: Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia,Footnote 44 Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Uruguay and Venezuela. All of these are presidential democracies that, despite sharing similar cultural characteristics and similar histories of (de-)colonization, show variation in our main variables of interest.

In contrast with the reduced number of items in more recent surveys, the 2008 wave of the Americas Barometer contains five questions that relate to various aspects of citizens’ political knowledge. The exact wording of these questions is contained in the online appendix (Table A.2). After testing for the internal consistency of these five items,Footnote 45 we constructed an index of factual political knowledge by creating an additive measure of correct answers (coded as 1) against incorrect and ‘don’t know’ responses (coded as 0). Thus the index varies from zero correct answers to five correct answers. The average number of correct answers across the eighteen countries is 2.62, but there is plenty of variation, as Figure 1 shows. Uruguay, with 3.5 correct answers on average, ranks first in our index, very closely followed by Honduras (3.41) and Argentina (3.37); Nicaragua, with 1.75 correct answers, is at the other extreme.

Fig. 1 Index of political knowledge by country Source: adapted from LAPOP 2008.

At the individual level, this study employs indicators of the standard antecedents of political knowledge (individual differences in motivation, resources and ability).Footnote 46 It is expected that the gender gap will be smaller among younger, more educated, less religious, white, working women who have fewer children at home, higher standards of living and higher political interest. It is also expected that the gender gap will be smaller for citizens living in big cities (where women are expected to have more political knowledge) and in rural areas (where both men and women are expected to have very low levels of political knowledge).

Once the individual-level antecedents of political knowledge are controlled for, this study explores the effect of the contextual dimensions discussed earlier on the gender gap. Two variables account for gender-bias signaling. First, to gauge gender differences in representative institutions, a measure of the percentage of women in the country’s parliament is used.Footnote 47 Secondly, gender differences in the labor market are accounted for by the ratio of estimated female- to male-earned income,Footnote 48 which ranges from 0 (complete inequality of earned income) to 1 (complete equality of earned income). We expect a smaller gender gap in countries with a greater percentage of women in parliament and in countries with higher equality of earned income.

Gender accessibility is captured through three variables. First, the average age of the main political partiesFootnote 49 is used as an indicator of party system institutionalization. The gender gap in knowledge is expected to be lower in countries with older party systems. Secondly, we employ the Gallagher’s index,Footnote 50 which ranges from 0 to 100 (higher values reflect less proportionality), as a measure of the disproportionality of electoral outcomes. It is expected that the gender gap in knowledge will increase as disproportionality increases. Thirdly, we employ Watts’ index of federalism, which distinguishes between unitary (0), hybrid unitary (0.5) and federal (1) countries.Footnote 51 The gender gap in knowledge should be smaller in less unitary countries.

Finally, the study controls for two other potential contextual determinants of knowledge. Economic development is measured as GDP per capita in US dollars, as provided by the World Bank’s World Development Indicators. It is expected that the gender gap in knowledge will decrease as economic development increases. Political freedom is measured using the Freedom House index of political rights,Footnote 52 which measures the quality of democracy from 1 (most free) to 7 (least free). The gender gap in knowledge is expected to be higher in countries with weaker political rights (although, as explained above, in Latin America it might also be the opposite).

Self-reported exposure to media news (a summative index of exposure to radio, TV, newspaper and internet news) is also controlled for, as such exposure may affect levels of political knowledge in general. Descriptive statistics of the aggregate- and individual-level variables employed can be found in the online appendix (Table A.1). The measurement of each of the independent variables is provided at the bottom of Table A.3.

Our empirical strategy is to estimate political knowledge as a function of all the standard antecedents at the individual level plus all the contextual variables using a two-level estimation (individuals and countries). By introducing a random intercept at the country level, we relax the assumption of independence of errors between respondents living in the same country and are able to introduce country-level variables with appropriate standard errors. Since we are interested in the differences between men and women, we need to include not only the main effect of each of the individual and contextual variables, but also an interactive term of each individual and contextual variable with gender.

Findings

We begin by presenting the size of the gender gap in political knowledge by country in Figure 2, which shows the average number of correct answers among men and women. As expected, political knowledge is significantly higher among men in all eighteen nations,Footnote 53 confirming previous findings analyzing data from industrialized democracies. There is also clear variation across countries. Argentina presents the smallest gender gap, with men correctly answering 0.28 more questions than women. At the other extreme is the Dominican Republic, where men correctly answered almost one more question (0.92) than women. The gender differences in political knowledge presented in Figure 2 are considerable if we take into account that the index ranges from 0 to 5 and that the average number of correct answers across Latin America is 2.62. The number of correct answers given by women across countries is 22 per cent lower on average than the number of correct answers given by men. This gender gap in political knowledge and its variation across countries clearly deserve an explanation.

Fig. 2 The gender gap in political knowledge across Latin America Source: adapted from LAPOP 2008.

To incorporate both individual and contextual information, we employ a hierarchical model with two different levels (individuals and countries). Table 1 shows the results of the estimation of the individual determinants of citizens’ political knowledge. Model 1 shows the magnitude of the gender gap without considering any respondent characteristics. On average, men provide a bit less than one additional correct answer than women (coefficient for the variable gender=0.76). Model 2 adds all individual predictors with the expectation that men and women have different access to resources and opportunities, and that these differences contribute to explaining the gender gap in knowledge. Finally, Model 3 adds the significant interaction terms of all the relevant individual-level independent variables and gender, with the expectation that men and women may respond differently to the same factors. Out of all the possible interactions, only three were statistically significant: education, urbanization and ethnicity.

Table 1 Individual-Level Determinants of the Gender Gap in Political Knowledge

Source: adapted from LAPOP 2008. Standard errors in parentheses. The measurement of all independent variables is provided at the bottom of Table A.3 in the online appendix. ***p<0.01, **p<0.05.

The results in Model 2 in Table 1 demonstrate the impact of resource differences on the levels of political knowledge of Latin American citizens. The number of correct answers increases with education, age and (subjective) standard of living. In addition to males, knowledge is also greater among citizens who are white, married, employed, declare themselves to be interested in politics and are intensively exposed to media news. Conversely, the level of knowledge appears to be lower for those with more children at home and for those living in a rural area.

The results also suggest that, even when individual differences in motivation, resources and ability are all taken into account, political knowledge continues to be significantly higher among men than it is among women. However, the magnitude of the effect of gender is reduced once all the individual determinants of knowledge are considered (the reduction is from 0.760 to 0.515=0.245). Thus it appears that compositional differences between men and women on the antecedents of knowledge help explain only part of the gender gap.Footnote 54 Put another way, part of the gender gap is explained by the fact that men in Latin American still have, on average, more socio-economic and cognitive resources than women.

To test the extent to which the same antecedents of knowledge might affect men and women differently, Model 3 in Table 1 shows the results of an additional estimation, in which we introduce interactions of all the relevant individual-level variables with gender. Surprisingly, most of the variables that have been identified in the literature as reducing the gender gap do not seem to be relevant in Latin America, as their interaction with gender is not statistically significant.Footnote 55 Thus the impact of gender on political knowledge does not seem to be conditioned by the number of children at home, labor market position, church attendance or income. Moreover, the gender gap in knowledge in Latin America does not appear to decrease among the youngest generations compared to their older counterparts, since the interaction term of age and gender did not reach statistical significance.Footnote 56 These results challenge the recurrent speculation in the literature that the gender gap in politics will disappear over time due to changes in socialization and generational replacement.Footnote 57

Model 3 in Table 1 shows the results of the estimation including only the significant individual-level interactions. Only three variables contribute to significantly reducing the gender gap: education, urbanization and ethnicity. Although education tends to increase the levels of political knowledge for both men and women, the effect is smaller for men, as can be appreciated by the negative sign of the interaction term. Comparing people with no formal education to those who have spent the longest amount of time in formal education (eighteen years) reduces the magnitude of the gender gap by 28 per cent.Footnote 58

The effect of urbanization turned was as expected. In Latin American rural areas, where men also have lower levels of political knowledge, the gender gap is greatly reduced, as demonstrated by the negative sign of the interaction term (rural×male). On average, the gender gap is 16 per cent lower in rural areas than in urban areas.Footnote 59 In urban areas, the gender gap is significantly lower in bigger cities (including capital and metropolitan areas), where women have easier access to political resources and therefore also have more political information than women in other areas. The average number of correct answers is 0.63 less for women in smaller cities and towns than it is for men, but this difference decreases to 0.48 in bigger cities (that is, a decrease in the gender gap of 21 per cent).Footnote 60

Finally, the difference between males and females appears to be smaller among white people. While non-white men give 0.54 more correct answers than non-white women, white men give 0.45 more correct answers than their female counterparts. Nevertheless, it is worth noting that the effect of ethnicity on the gender gap ceases to be significant when contextual-level variables are controlled for (see Table 3), which is discussed in more detail below.

We next introduce interactions between gender and each of our aggregate variables. The results are shown in Table 2.Footnote 61 As expected, the gender gap is smaller in decentralized countries (see the corresponding column of Model 5) and in countries that have older political parties (see the corresponding column of Model 4), a greater percentage of women in parliament (see the corresponding column of Model 7) and a smaller sex difference in earned income (see the corresponding column of Model 8). Smaller gender gaps are also found in countries with higher levels of economic development (measured as GDP per capita; see the corresponding column of Model 9) and more political freedom (see the corresponding column of Model 10, recall that this variable goes from a higher to lower degree of freedom), our two aggregate-level control variables. However, contrary to our expectation, this study does not find evidence that sex differences in political knowledge in Latin America depend on a country’s electoral disproportionality (see the corresponding column of Model 6).

Table 2 Contextual Determinants of the Gender Gap in Political Knowledge

Source: adapted from LAPOP 2008. Standard errors in parentheses. The following control variables are not shown (but are included in the estimation): Education (years), Urbanization, Married/cohabiting (ref: Single), Religiosity (service attendance), Subjective standard of living, Number of children at home, Labor market position: Employed, Inactive (ref: homemaker), Age, Age squared, Political interest, Exposure to media news (summative index based on radio, TV, newspapers and internet news exposure). Table A.3 in the online appendix shows the control variables at the individual level (and the measurement of all independent variables). ***p<0.01.

After specifying each of the country-level variables separately, an additional equation was estimated (Model 11 in Table 3), in which all significant interaction terms were specified simultaneously: party age, percentage of women in parliament, income equality, political freedom and GDP, together with education, ethnicity and degree of urbanization of the place of residence. This strategy is useful to test which variables appear more relevant in contributing to increasing or decreasing the gender gap in knowledge in Latin America. Again, other individual-level independent variables are not shown in Table 3 but are included in the estimation.Footnote 62

As can be seen in Table 3, when all these variables are simultaneously specified, the effect of federalism, economic development and political freedom all cease to be statistically significant, even though their coefficients retain the right sign. Ethnicity, which interacted significantly with gender in Model 3, ceases to be significant when contextual variables are introduced. However, all the other interactions continue to reach statistical significance in the final model.

Table 3 Contextual Determinants of the Gender Gap in Political Knowledge. Full models.

Source: adapted from LAPOP 2008. Standard errors in parentheses. Control variables at the individual level are not shown (but are included in the estimation). Online Appendix Table A.4 shows the control variables at the individual level, whereas Table A3 shows the measurement of all independent variables. ***p<0.01, **p<0.05

Our findings are thus in line with our expectation that the contextual setting influences gender differences in political knowledge through two specific mechanisms: gender-bias signaling and gender accessibility. Regarding gender-bias signaling, the magnitude of the gender gap in knowledge significantly decreases as the percentage of women in parliament (the political gender-bias signaling dimension) increases, and as income equality between females and males (the economic gender-bias signaling dimension) increases.

The gender accessibility mechanism also appears to influence gender differences in knowledge in Latin American countries, but less through the effect of power-sharing institutions and more through the effect of the institutionalization of the party system. Institutionalized party systems provide policy stability to parties and better opportunities for women’s activists to access party leadership and influence the political agenda, which contributes to a decrease in the magnitude of the gender gap in knowledge.

We rely on a graphical presentation of the results to more clearly assess the magnitude of the impact of the aggregate variables. To this end, and following the recommendations of Kam and Franzese,Footnote 63 the marginal effects on gender differences in political knowledge have been computed (that is, the difference between the marginal effect of each variable on men’s political knowledge minus its effect on women’s political knowledge), along with their associated standard errors. Figure 3 shows how the gender gap in knowledge is clearly reduced in countries with older party systems that provide stable settings for women to access the agenda and leadership of political parties. In our sample, the effect ranges from a difference of 0.60 questions when party age is five (minimum) to a difference of 0.35 when party age is ninety-five (maximum). This implies an overall reduction in the magnitude of the gender gap in knowledge of about 42 per cent. If we consider that the average gender gap in knowledge amounts to 0.66 questions, this is clearly an important effect.

Fig. 3 Effect of party age on the gender gap in political knowledge (with 95 per cent confidence intervals) Source: based on the estimations presented in Model 12 of Table 3.

A very similar reduction can be seen in countries with a higher proportion of women in parliament (Figure 4). On average, men provide 0.61 more correct answers in countries with the minimum percentage of women in Congress (9 per cent), which is reduced to 0.33 when the maximum (39 per cent) is reached. This involves an overall reduction of almost half (46 per cent) in the magnitude of the gender gap in political knowledge. The presence of more women in the legislature signals that women play a relevant role in the political sphere, thereby motivating women to get involved and informed about politics, and consequently reducing the knowledge differences between men and women.

Fig. 4 Effect of percent of women in parliament on the gender gap in political knowledge (with 95 per cent confidence intervals) Source: based on the estimations presented in Model 12 of Table 3.

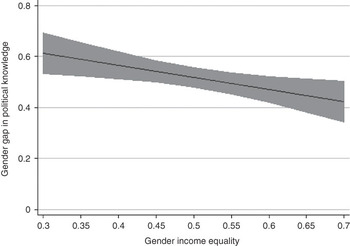

Likewise, the economic gender-bias signaling dimension appears to function in Latin America. In fact, higher income equality between men and women is associated with a smaller gender gap in political knowledge (Figure 5). The difference between men and women is 0.61 correct questions in the most unequal context in our sample (female- to male-earned income ratio=0.3). The gap, however, decreases significantly in countries with greater levels of income equality between genders, reaching 0.42 when the maximum level of equality in the sample is reached (female- to male-earned income ratio=0.7). This involves an overall reduction of almost one-third (31 per cent) in the magnitude of the gender gap in political knowledge.

Fig. 5 Effect of income equality on the gender gap in political knowledge (with 95 per cent confidence intervals) Source: based on the estimations presented in Model 12 of Table 3.

Lastly, the effects of federalism, political rights and economic development are much smaller than those of the other aggregate variables, and do not appear to be conditioned on gender (since the interaction term of all of them with gender did not reach statistical significance at p<0.05). The implications of these findings for both the study of political knowledge and for the functioning of representative democracy are discussed in the last section.

Discussion and Conclusions

This study analyzes the relationship between gender and political knowledge in eighteen Latin American countries using data from the 2008 Americas Barometer survey. The findings show that, after controlling for individual differences in motivation, resources and ability, political knowledge continues to be significantly higher among men than women across all countries analyzed here, which confirms previous findings in Europe, the United States and Canada. However, the magnitude of the gender gap varies to a great extent across Latin American countries.

A substantive relevant finding of this article is that sex differences decrease as citizens’ level of education increases. This suggests that a considerable increase in the general level of education in Latin America might contribute to reducing the gender gap in politics to about one-fourth its current size. In addition, gender differences appear smaller in rural areas (where both men and women have low levels of political knowledge) and in bigger cities (where women’s levels of political knowledge is higher). Surprisingly, evidence relating to the differential effects of other individual factors, such as number of children or economic status, was not found. Furthermore, the size of the gender gap in knowledge does not appear to depend on age, thereby challenging previous expectations in the literature of a decrease in the size of the gender gap in politics over time due to changes in socialization and generational replacement.Footnote 64 These findings are relatively pessimistic about the potential of closing the gender gap in the near future, and suggest that Latin American countries probably need more radical changes in socialization.

But perhaps more importantly, this study demonstrates that context also matters when explaining cross-country differences in the magnitude of the gender gap in knowledge in Latin America. We argue that this may take place through two interrelated pathways: gender-bias signaling and gender accessibility. With regard to gender-bias signaling, we find that as women’s descriptive representation increases, the gender gap in knowledge decreases: for example, if Costa Rica (the country with the highest level of women’s representation in parliament) is compared with Brazil (which has the lowest level), the size of the gender gap in knowledge in the former is, on average, one-third smaller than in the latter. This study also demonstrates that an ignored factor in previous studies – income equality between sexes – appears to be highly relevant in reducing the magnitude of the gender gap in knowledge. If we compare Nicaragua (the most unequal country in our sample) to Colombia (the most equal) the size of the gender gap in knowledge in the former is, on average, 37 per cent smaller than in the latter.

These findings suggest the need to incorporate socio-economic explanations about the gender gap in politics at the individual level (measured through citizens’ socio-economic resources) as well as the contextual level. They also suggest that the presence of acute gender biases in both political and economic aspects of the public sphere may have important symbolic (de-)mobilization effects and contribute to enlarging the gender gap in knowledge.

With regard to the accessibility of the political system, this study shows that the greater the consolidation of party systems, the more gender differences in knowledge diminish. On average, gender differences decrease from 0.60 in El Salvador (the country with the lowest level of party system institutionalization) to 0.35 in Uruguay (which has the highest level). This implies a reduction of 42 per cent in the size of the gender gap. We interpret this finding as evidence of the gender accessibility mechanism, according to which stable institutions that facilitate women’s involvement in politics and sustained access to the political agenda may also help reduce the gender gap in political knowledge. This evidence highlights the harmful effect that political instability can have on enlarging sex differences in political knowledge in Latin America.

The findings presented here also suggest the need to conduct further research on the topic in a larger geographical area and possibly over a longer period of time. We urge researchers to continue pushing for the inclusion of a range of comparable knowledge measures that result in valid representations of what people know about politics across countries. In this respect, the inclusion of four knowledge items standardized across countries in the fourth module of the CSES appears to be promising.Footnote 65 Other international survey programs could also adopt this strategy.

A last but very important implication of these findings is that what people know about politics is not only a function of their capabilities and motivation, but also of the opportunities available where they live to become informed about politics, which also confirms previous findings related to Europe.Footnote 66 Moreover, socio-economic and institutional settings that provide opportunities for women to influence the political agenda and to play a central role in the public sphere significantly contribute to reducing the magnitude of the gender gap in knowledge. Consequently, this gap does not necessarily need to perpetuate itself over time. It all depends on the capacity of politicians and citizens to create opportunities for women to increase their level of knowledge. This will help women know as much as men about what governments are actually doing, which will enable them to hold governments accountable for their actions and create additional incentives for governments to be responsive to all citizens.