1. Introduction

The Kulu region of Himachal Pradesh has many preserved historical documents, including inscriptions, in Brāhmī and Ṭākarī scripts; only Chamba has more. Vogel (Reference Vogel1911)Footnote 1 and Chhabra (Reference Chhabra1957)Footnote 2 have thoroughly documented and translated the known inscriptions of Chamba; however, no such detailed and comprehensive corpus is available on the inscriptions of the Kulu region. The seven-line Ṭākarī inscription discussed in this article is carved on the wooden doorjamb of the celebrated Hiḍimbā Devī temple at Manali in Kulu (Figure 1). The temple of the goddess Hiḍimbā is situated a little above the town of Manali (latitude 32°10’ north and longitude 77°15’ east) amidst the grove of deodar trees at Dhungri. It is a three-tiered Pagoda style of temple crowned with a round canopy studded with a brass pitcher and a trident. The entire wooden façade of the temple is decorated with the carvings of Brahmanical gods and goddesses, including Śiva-Pārvatī, Viṣṇu-Lakṣmī, Mahīṣāsuramardinī, Sūrya, Rāma, Lakṣmaṇa, Hanumāna, and the Navagraha panel. The doorframes consist of three superimposed broad pedyās (jambs) and uttaraṅgas (lintels), and Gaṇeśa is carved in the centre of the lalāṭa-bimba.

Figure 1. A front view of Hiḍimbā Devī temple, Manali. Photo: Laxman S. Thakur

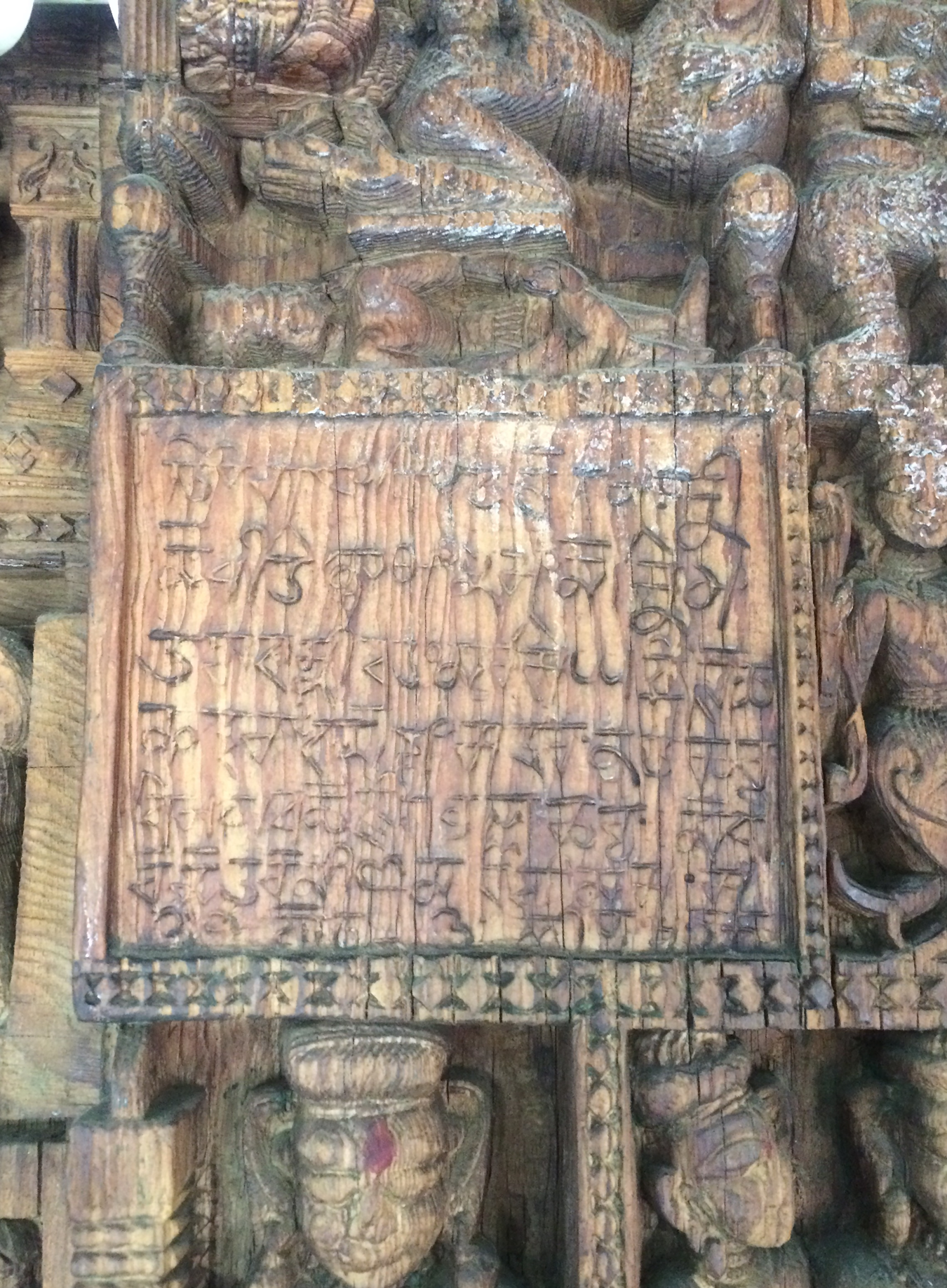

The inscription is written in the Ṭākarī script on a wooden panel measuring 8.2 cm by 7.4 cm on the right side, which is known in the Chamba region by the name of Devashesha. This inscription is briefly mentioned by J.C. Murray Aynsley, who visited Manali in 1875 and remarked that “on one of the door-posts was a short inscription, which, we were informed, had never been deciphered” (Murray Aynsley Reference Murray Aynsley1879: 282).Footnote 3 Hirananda (Reference Hirananda1907–08: 267, 275) commented briefly on the inscription.Footnote 4 In his analysis of the copper-plate grant of Bahādur Singh of Kulu, Vogel also refers to it very briefly but has wrongly deciphered its date (Vogel Reference Vogel1903–04: 264).Footnote 5 It has not been translated in extenso by Hirananda, Vogel, or any other scholar. I offer for the first time a full transcription and translation of this inscription. The readings and calculation of Saṁvat and praviṣṭe and their corresponding year and day of the month differ from those of both Vogel and Hirananda (Figure 2).

Figure 2. A seven-line Ṭākarī inscription carved on the doorjamb of the temple.

Photo: Laxman S. Thakur

The writers of the Kulu inscriptions normally follow the Śrī Śāstra Saṁvat or Saptaṛṣi Saṁvat in recording the dates either in constructing the temples or donating the bust (mohrā) of devatās to the temples by rulers, their family members, and other donees. They record only the years and omit the century. In some instances, the inscribers have added the corresponding years of the Vikramī Saṁvat or Śaka eras. A fairly accurate formula for calculating the dates given in Śāstra Saṁvat or Saptaṛṣi Saṁvat has been suggested by Kielhorn (Reference Kielhorn1891: 151), who has pointed out:

Thus, a current Saptarshi era 36 would, disregarding the hundreds, correspond to an expired year (36 + 25 =) 61 of the Kaliyuga; to an expired Śaka year (36 + 46 =) 82; to an expired northern Vikram year (36 + 81 = 117 =) 17; and to a year 36 + 24/25 = 60/61 of our own era.Footnote 6

In the Kulu region, the addition of 24 to the Śrī Saṁvat provides an accurate date for the inscribed epigraphs. This is supported by two Ṭākarī inscriptions, dated in the Śrī Saṁvat, found on the foundation wall of the Murlīdhara temple at Chaihni in the Banjar area of Kulu. Two of them are inscribed with dates in both Śāstra and Vikramī Saṁvat. The first is dated in the Śrī Saṁvat 50, and Vikramī Saṁvat 1731. Thus, adding 50 + 24 = 74 = ad 1674, and Vikramī Saṁvat would correspond to (1731–57 =) ad 1674. The second inscription is dated Śrī Saṁvat 68 (i.e. 68 + 24 = 92 =) ad 1692. The Vikramī Saṁvat 1749 would also be equivalent to ad 1692 (1749–57 =) ad 1692. Alexander Cunningham has provided a comprehensive 69-pages of general tables of corresponding dates in various eras, including the Saptaṛṣi Saṁvat and Vikram Saṁvat,Footnote 7 along with conversion tables to the Gregorian calendar from 60 bc to ad 2000 (Cunningham Reference Cunningham1883: 135–203).

2. A seven-line Ṭākarī inscription on the doorjamb of the temple

Text

1. oṁ gaṇeśaya [xx]Footnote 8 pata(?) je nakha. śrī

2. devī hiḍīmā pramaFootnote 9 de śrī ma.

3. hārāja śrī bahādur siṁgha jo eka

4. chhatraFootnote 10 rāja dehī satara. nata karu

5. vina/bina [x] eka joga bhalā karu. devī

6. re deureFootnote 11 dīṇa darogī dam. saṁ

7. 27 jeṭha pra 2. līkhaFootnote 12 ṣatama.Footnote 13

The most interesting part of the inscription is its dating method. It refers to some unspecified Saṁvat 27 and the month of Jeṭha (Jayeṣṭha) praviṣṭe 2 instead of 20 as deciphered by both Vogel and Hirananda. Vogel has incorrectly deciphered the numeral 7 as 9. In Kulu Ṭākarī there is very little difference between the depiction of numerals 7 and 9. The numeral 9 (nine) is slightly curved at the lower end whereas 7 (seven) is almost kept straight down after the use of a top circular loop. Also, the pra, an abbreviation of praviṣṭe in this inscription, is read as 2 instead of 20; Vogel has misread the dot used after 2 for zero, and overlooked the use of similar dots that are used for indicating full stops, or as a mark of punctuation in lines 1, 2, 4, 5 and 6; and finally, after 2 in the last line. In Kulu, zero is always indicated by a circle, not by a dot. At least two letters of the first and one letter of the fifth lines are totally effaced; however, that has not substantially altered the translation and meaning of the inscription.

Let me briefly discuss the inscription's orthographic and palaeographic characteristics. The inscription is written in the cursive Ṭākarī script used in the western Himalayan region from the fourteenth to the nineteenth centuries, with many variants that are found in Chamba, Kangra, Mandi, Sirmaur, and Bushahr. The language of the inscription is the Kulluvī dialect of Western Pahāṛī. The sign of vowel o is regularly used with two strokes above the consonants. One of the typical features of the inscription is the use of a single straight stroke between the two letters for employing two curved strokes on either side to indicate vī in the word devī and hi in Hiḍimbā in line 2. The use of a loop at the lower end towards the left in lingual ḍa is beautifully carved. A simple straight stroke above a letter represents e; for example: je (line 1), de (line 2: twice), eka (line 3), dehī (line 4), devī (line 5), and re deure (line 6). No differentiation has been made between the use of ta and u and va and ba. For punctuation marks the inscriber has simply used a dot at least six times. In the last line, ṣa is used for kha, which is very commonly observed in the Ṭākarī inscriptions from the Kulu region.

3. Translation

Obeisance to the Gaṇeśa. Illustrious Lord (param deva)Footnote 14 Śrī Mahārāja Bahādur Singh who has ruled authoritatively (gave good governance) (eka chhatra rāja dehī) gave or offered a thin (pata je) golden nose ring (nakha) to the goddess Hiḍimbā and paid homage (nata karu)Footnote 15 at the temple. He has done a meritorious deed (bhalā karu) by performing a jaga or a yajña (eka joga) at the temple of the goddess. Written date-wise (darogī dam = tithivāra) in Saṁvat 27, Jeṭha praviṣṭe 2 (corresponding to ad 1551). The end.

4. Concluding remarks

Vogel was pleased to record that he had deciphered the date of the inscription and was able to “date one of the interesting monuments of the Kuḷḷū valley” (Vogel Reference Vogel1903–04: 264).Footnote 16 As pointed out earlier the Śāstra Saṁvat recorded in the inscription is the 27th year, not the 29th as read by Vogel, and thus corresponds to ad 1551. The space for the inscription is pre-planned, while dividing the wooden panels for carvings to be accomplished on the façade of the temple. It was not possible to inscribe such a long inscription and carve out an ornamented rectangle in the limited space after the completion of the carvings on the doorjambs. As pointed out in the translation given above, it records the name of the king Bahādur Singh of Kulu, who was perhaps responsible for constructing the present temple (deura) of the goddess Hiḍimbā. According to the genealogical list of the Kulu rulers, Bahādur Singh was the 75th ruler of the Kulu state; however, there is no archaeological record of the first 71 rulers. Only two rulers of the Pāl dynasty, Udhraṇa Pāl and Sidh Pāl, are briefly mentioned in the Ṭākarī inscriptions. Bahādur Singh's name also occurs in the copper-plate grant, dated in the Śāstra Saṁvat 35 (ad 1559). He consolidated his position in the Beas valley from Manali to Bajaura as he granted a piece of cultivable land to Pandit Ramāpati, at the time of the marriage of his three daughters to Pratāp Singh of Chamba. This piece of land was situated at Hāṭ near Bajaura. The goddess Hiḍimbā was the patron deity of the rulers of Kulu state until the time of Jagat Singh (ad 1637–72) who brought the image of Raghunātha from Ayodhya to Kulu, some time in the mid-seventeenth century, and ruled the state on his behalf. From then on, the rulers of Kulu state called themselves the golāma of Raghunātha (servants/slaves of Raghunātha). The construction of a huge temple of the patron deity of the state at Manali was an act of piety and prestige for Bahādur Singh. The offering of a nose ring for the mohrā (bust) of the goddess, which was donated by Udhraṇa Pāl in ad 1418,Footnote 17 and a jaga at the temple complex, suggests that admirable work was done on the completion, or consecration of the temple of the goddess Hiḍimbā.

In the decipherment of the inscription inscribed on the doorjamb of the Hiḍimbā temple, Manali, with a complete translation and the correct readings of the Saṁvat and praviṣṭe, makes the temple of Hiḍimbā older by two years eighteen days than do the readings of the Saṁvat and praviṣṭe carried out by J. Ph. Vogel in 1903–04, and his faithful assistant Hirananda in 1907–08. The present structure of the temple was completed in ad 1551 and all wooden carvings on the windows, doorframes, and the entire façade were accomplished by that date.

Acknowledgements

The article is based on the field study conducted in situ on 15–16 April 2016. The author would like to thank two anonymous referees for BSOAS for useful and precise comments on an earlier draft.