‘Under international law of investments […] investors enjoy by themselves a number of rights […]. What about the investor’s obligations arising of the investment according to international law?’Footnote 1

I. Introduction

The international law protecting foreign investment contains substantive and procedural rights for investors, but hardly any obligations. This one-sidedness of a legal regime which only entrusts rights, but imposes no duties on powerful economic actors, in particular multinational enterprises, contributes to its ongoing legitimacy crisisFootnote 2 prompting calls for a rebalancing of international investment law.Footnote 3 Such calls have not only been voiced by academia and civil society, but increasingly by the investment law community, including investment tribunals as the above-mentioned quote of the recent decision of the tribunal in the matter Aven v Costa Rica aptly demonstrates.Footnote 4

In many cases, calls for investor obligations have been framed in human rights language linking the idea of investor obligations to duties of economic actors to respect human rights.Footnote 5 This is where the debates on the reform of the investment regime and on business and human rights meet. For international investment law, one element of its reform could include direct obligations of investors to observe national and international laws, including human rights.Footnote 6 For human rights law, the expectation that business entities should not cause or contribute to adverse impacts of human rights is part of the second pillar of the United Nations Guiding Principles (UNGPs) on Business and Human Rights, the corporate responsibility to respect human rights.Footnote 7 Investor obligations could therefore contribute to the rebalancing of international investment law and to the implementation of the UNGPs. In addition, they could go beyond the mere corporate responsibility to respect human rights and establish binding legal obligations for businesses to do so.

Whether the lack of investor obligations in international investment law is considered the investment regime’s cardinal failure or the logical consequence of the vulnerability of foreign investors, remains fiercely debated. Regardless of one’s position in this debate, recent developments in treaty-making and treaty-application suggest that there is a growing demand to recognize the misconduct of foreign investors, including their involvement in human rights violations, in international law generally and international investment law specifically. This demand can be met by including investor obligations explicitly in new treaties or by deriving them from existing treaties through treaty interpretation.

Drafting and adopting new treaties may seem preferable from the perspective of legal clarity and security while often practically and politically difficult. Interpreting existing treaties in new and sometimes surprising ways may lead to legal innovations which would have been difficult if not impossible to legislate. Yet, despite the invaluable contribution of progressive case law, deriving new legal principles without an explicit basis in legal instruments may seem problematic from a methodological and legal philosophical perspective.

H.L.A. Hart addressed the dilemma between innovative interpretation of existing law and creation of new law through jurisprudence in 1977 with the figurative dichotomy of the nightmare and the noble dream.Footnote 8 Hart noticed the enormous power of US courts in not only applying, but also ‘making law’. In particular, he pointed to the US Supreme Court and its many ‘legal inventions’, asking how these can be reconciled with general principles of jurisprudence.Footnote 9 On the one side, Hart seemed to fear that law-making judges could become a ‘nightmare’.Footnote 10 On the other side, he was also hoping that judges could be pursuing the ‘noble dream’ of an application of the law which was not driven by judicial activism.Footnote 11

This article borrows Hart’s concepts to assess the different approaches currently discussed and developed in international human rights and investment law to establish investor obligations.Footnote 12 The article first develops a general framework of analysing and comparing these approaches. Subsequently, the attempts to include direct obligations of business entities in international human rights treaties are discussed. Despite earlier indications, the recent initiative to create a legally binding instrument on business and human rights will most likely not include direct obligations for business entities. Next, the article turns to developments in international investment law. After briefly contextualizing the question about investor obligations in the wider debate on investment law and human rights, the article assesses the development of investor obligations in new international investment treaties and through the interpretation and application of existing international investment agreements. Arguably, the former will not lead to binding obligations in the foreseeable future and the latter rests on methodologically questionable grounds. Consequently, the article suggests that the way forward will require domestic legislation in host and home states to establish investor obligations which can be taken into account when interpreting existing treaty clauses. It is claimed that such an endeavour may be practically more viable and methodologically sounder than a pure reliance on international investment law. The article concludes that this approach would reflect recent trends both in investment law reforms as well as the business and human rights movement, thereby establishing a pluralistic legal framework of obligations for foreign investors.

II. A Framework for the Establishment of Investor Obligations in International Law

International investment law and international human rights law are two distinct fields of international law. Even if one subscribes to the view that they may have a common root in the customary law protecting aliens,Footnote 13 the two regimes rest on different legal sources, contain different legal principles and are applied and administered in different institutional settings.Footnote 14 This does not exclude the possibility of overlaps in certain situations, but generally the two regimes remain separate and have distinct features.Footnote 15

International investment law rests on a web of thousands of bilateral investment treaties and other treaties with investment protection provisions.Footnote 16 It contains general standards of protecting foreign investors and their investment, including compensation for expropriation as well as guarantees of fair and equitable treatment and non-discrimination of the investor. Investment treaties are applied by ad hoc tribunals established at the request of a foreign investor and based on the claim that the host state treated the investor in a manner which violates the term of the respective investment agreement.

In contrast, human rights law is enshrined in global and regional human rights treaties which contain rights of individuals and respective obligations of states to respect, protect and fulfil those human rights. International human rights treaties are applied by regional human rights courts or special bodies established on the basis of human rights treaties.

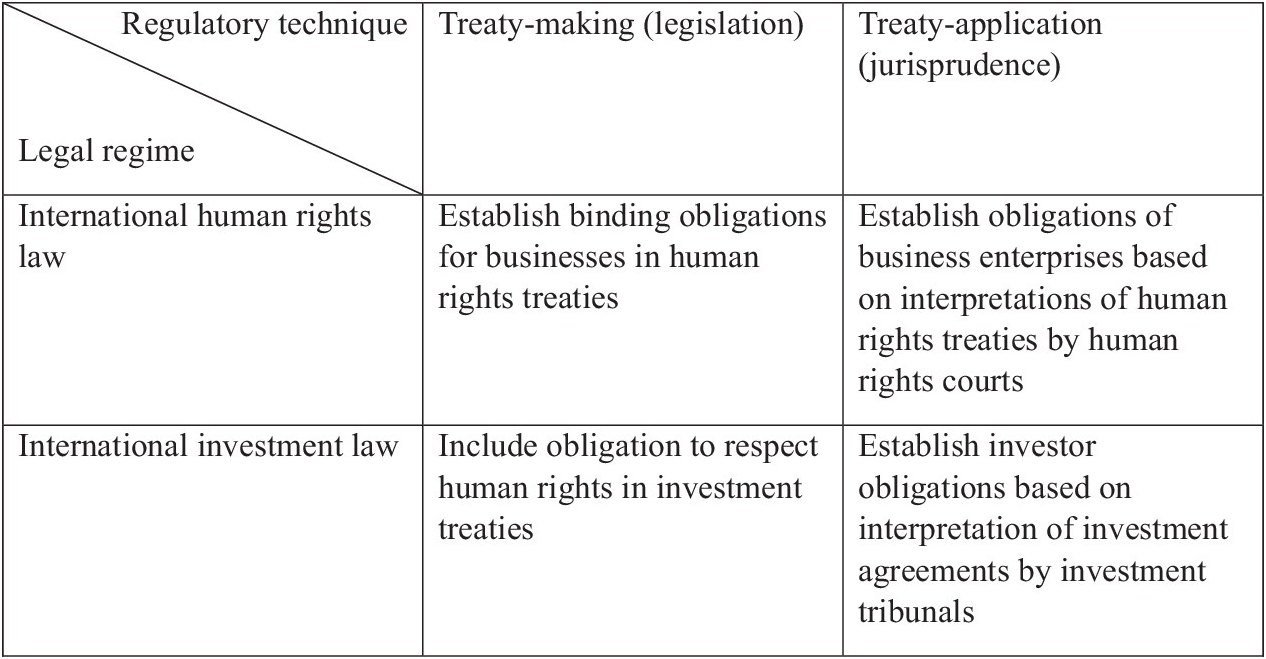

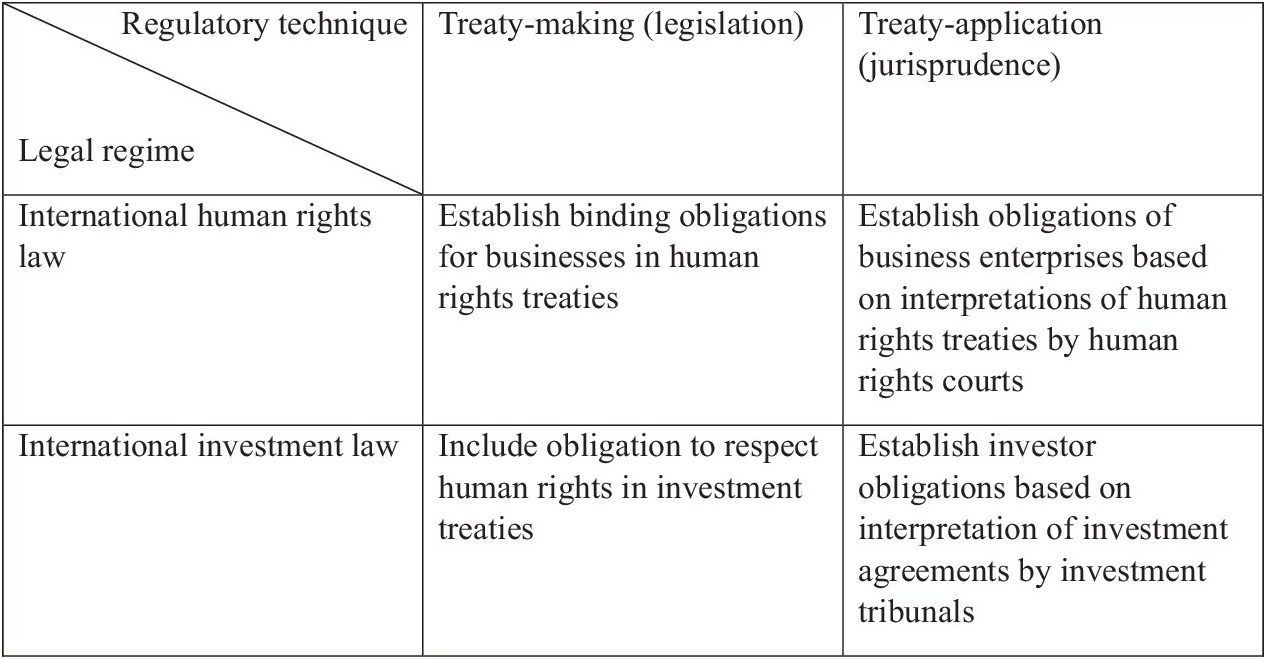

In light of the distinct nature of the two regimes, a framework to analyse the development of investor obligations should distinguish the investment and the human rights regime. Within each regime, the development could be based on a legislative approach involving the drafting of new treaties or the inclusion of new provisions in existing treaties or a judicial approach relying on the interpretation of existing treaties by international courts and tribunals. The two regimes and the two approaches can be combined in a two-by-two matrix as illustrated in Table 1.

Table 1. Four approaches to establish human rights obligations of businesses in international law

As will be discussed below, three possible approaches have already some basis in actual international practice. Attempts to establish binding obligations for businesses in human rights law can be traced back to the late 1990s and have lately been again at the focus of an Intergovernmental Working Group of the Human Rights Council. Recent investment treaties have increasingly referred to corporate responsibilities including in some cases also human rights obligations. Tribunals interpreting and applying investment treaties have been asked to develop investor obligations based on investment treaties or other applicable law. However, the fourth approach, i.e., the establishment of human rights obligations of businesses on the basis of existing human rights treaties by human rights courts or treaty bodies, has not yet gained any practical relevance.Footnote 17 While such an approach would not be unthinkable, it remains highly unlikely and difficult to conceptualize because human rights bodies currently only accept states as respondents and not private entities. In light of this jurisdictional limitation it is therefore not surprising that there have been no cases so far in which it has been argued by the claimants, let alone accepted by a court or treaty body in a concrete case, that an investor or business entity is directly bound by human rights obligations. This is why this approach will not be discussed further in this article.Footnote 18

III. Human Rights Obligations of Business Entities in International Human Rights Law

States are the primary duty bearers of international human rights obligations. Even though the Universal Declaration on Human Rights of 1948 contains language which suggests that the drafters assumed that individuals and ‘organs of society’ could also bear obligations under human rights law,Footnote 19 human rights treaties do not contain any explicit obligations for individuals or business entities.Footnote 20 This does not exclude the possibility to interpret human rights law in such a way that it also contains obligations for non-state actors as suggested by a number of commentators.Footnote 21 However, so far no international adjudicative body or special committee established to hear cases on the basis of human rights treaties interpreted an existing treaty in this manner.

This is why the debate and practice focus on creating new norms that would explicitly establish binding obligations of business entities. This would be possible without deviating from the current model of international law, because states can create binding norms for non-state actors through international law.Footnote 22 Such attempts first emerged in the international human rights context when the discussion on binding norms for multinational enterprises moved from the Commission on Transnational Corporations to the Sub-Commission on the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights Norms in 1997.Footnote 23 However, the Norms on the Responsibilities of Transnational Corporations and Other Business Enterprises with Regard to Human Rights developed by the Sub-Commission in 2003 remained a draft and were not further pursued due to political opposition.Footnote 24 Instead, the debate focused subsequently on various international non-binding standards establishing a corporate responsibility to respect human rights, most prominently in the UNGPs adopted by the UN Human Rights Council in 2011.Footnote 25

The idea of legally binding norms for business entities was reintroduced to the agenda of the UN human rights regime in 2014 with the establishment of the Open-ended Intergovernmental Working Group (OEIGWG) on transnational corporations and other business enterprises with respect to human rights entrusted with the mandate ‘to elaborate an international legally binding instrument to regulate, in international human rights law, the activities of transnational corporations and other business enterprises’.Footnote 26 The background for the establishment of the OEIGWG was the idea of creating binding obligations for business entities in an international human rights law instrument. Consequently, the discussions and debates in the first and second session of the OEIGWG in 2015 and 2016 focused inter alia on the scope and possible content of such obligations.Footnote 27

In 2017 the Chairmanship of the OEIGWG published a paper with possible elements of a treaty on business and human rights (the ‘Elements Paper’).Footnote 28 It contained the possibility of obligations of transnational corporations such as the obligation to comply with all applicable laws and respect internationally recognized human rights, wherever they operate, and throughout their supply chains. Furthermore, the Elements Paper proposed that transnational corporations shall prevent the negative human rights impacts of their activities and provide redress. In addition, transnational corporations should design, adopt and implement internal policies consistent with internationally recognized human rights standards and establish effective follow-up and review mechanisms, to verify compliance throughout their operations. Finally, the Elements Paper referred to an obligation of transnational corporations to refrain from activities that would undermine the rule of law as well as governmental and other efforts to promote and ensure respect for human rights, and to use their influence in order to help promote and ensure respect for human rights. These proposals of the Elements Paper would have established significant and far-reaching binding human rights obligations for private corporations in the field of human rights.Footnote 29

However, in light of the fierce opposition of many states towards such an approach, the first textual draft for a treaty published by the Chairmanship of the OEIGWG in July 2018 (‘Zero Draft’) did not contain any such obligations.Footnote 30 Instead, the Zero Draft only focused on state obligations, including obligations to regulate economic activities of a transnational character and to provide access to judicial remedies for victims of human rights violations. For those who hoped that the treaty process would finally lead to binding international legal obligations of business entities, the Zero Draft was disappointing.Footnote 31

It seems that the support for direct binding obligations for business entities in the treaty on business and human rights has not grown stronger within the international community since the publication of the Zero Draft. In fact, the Revised Draft for the treaty published by the Chair of the OEIGWG in July 2019Footnote 32 pursues the same approach as the Zero Draft concerning the question of binding obligations. While some language in the Preamble seems to be reminiscent of the idea that business entities are required to respect human rightsFootnote 33, none of the operative articles of the Revised Draft proposed by the Chair contains any obligations which would be directly binding on business entities.Footnote 34

In light of the two drafts, it is unlikely that the treaty-drafting process in the OEIGWG will lead to the establishment of direct obligations of business entities. At this juncture, it seems that investor obligations will not be expressly included in human rights treaties at the global level for the foreseeable future. While proponents of binding human rights norms for business entities may find this development deplorable, it may be a necessary compromise considering the current state of the debate among states.Footnote 35

IV. Human Rights Obligations of Investors in International Investment Law

The relationship between international investment law and human rights has been subject to debates in academia and practice for more than a decade.Footnote 36 Generally, the debate manifests itself in two dimensions. The first dimension revolves around the argument that investment treaties may limit the possibilities of states to regulate economic activities in pursuance of their human rights obligations. It is often claimed that investment agreements impose a ‘chilling effect’ on states by restricting regulatory space necessary, inter alia to protect human rights.Footnote 37 International investment agreements and arbitration practice may therefore conflict with human rights, because the latter would require certain state measures which the former would inhibit.Footnote 38 For example, if investment agreements limit policy options for states to reduce the consumption of tobacco, they may have a negative effect on the state’s obligation to protect the human right to health.Footnote 39 Similarly, if investment agreements restrict possibilities to impose regulations on private corporations supplying drinking water, the human right to water may be negatively affected.Footnote 40 In these situations, the question arises if human rights obligations of states can be used as justification of state measures and therefore as defence against claims that these measures violate investment treaty obligations.Footnote 41 Another aspect in this context concerns the question of a hierarchy between international investment agreements and human rights treaties if the former conflict with obligations of the latter.Footnote 42

The second dimension of the relationship between international investment law and human rights concerns human rights obligations of investors. Instead of justifying state actions based on the duty to protect, human rights would be used to assess the behaviour of investors. In the above-mentioned examples, it could be asked if the investor’s behaviour that triggered the respective state action constituted a violation of the investor’s own obligations under human rights law. As pointed out above, human rights treaties do not currently contain binding obligations for business entities, and this will not change in the near future. Hence, obligations of investors would need to be established in international investment agreements or through the interpretation and application of these agreements by investment tribunals.

A. Obligations to Respect Human Rights in International Investment Agreements

Incorporating investor obligations in international investment treaties constitutes an important element of the reform process of international investment law.Footnote 43 Human rights obligations of investors in international investment agreements could be established through incorporating international standards such as the Organisation for Economic and Co-operative Development (OECD) Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises in investment agreements as binding norms,Footnote 44 or through direct investor obligations.Footnote 45

1. Direct Investor Obligations to Respect Human Rights

The most straightforward approach to establish investor obligations in international investment law is the incorporation of norms which contain explicit duties of investors.Footnote 46 In this respect, international investment agreements could expressly require investors to respect human rights. Until recently, this option only existed in some model bilateral investment agreements which had not yet been transformed into actual agreements.Footnote 47

However, on 3 December 2016 Morocco and Nigeria signed the first international investment agreement which contains a clause establishing that investors need to respect human rights.Footnote 48 Even though the agreement is not yet in force, it has already attracted considerable academic and political attention.Footnote 49 Article 18 para 2 of the Morocco–Nigeria Bilateral Investment Treaty (BIT) states: ‘Investors and investments shall uphold human rights in the host state’. This paragraph is part of the general article entitled ‘Post-establishment Investor Obligations’ in that treaty, which also includes the obligation to act in accordance with core labour standards (Article 18 para 3) and the obligation not to circumvent international environmental, labour and human rights obligations of the host and/or home state (Article 18 para 4).

While it is clear that Article 18 para 2 of the Morocco–Nigeria BIT contains a direct and binding obligation as indicated by the word ‘shall’,Footnote 50 its content is less than clear. The first ambiguity concerns the duty-bearers. Usually, duty-bearers of human rights are persons, either states and other public entities or as in the present case investors, i.e., natural and legal persons. However, it is difficult to imagine how ‘investments’ – property or other assets – can have legal duties in addition to investors. However, it is suggested that the clause should not be interpreted in a strict literal meaning, but that it requires investors to ensure that their investments do not have any negative impacts on human rights.

Secondly, it is puzzling why the clause requires investors and investments to ‘uphold’ human rights. Standard human rights terminology refers to the obligation to respect, protect and fulfil human rights. It is unclear if the term ‘uphold’ would have a different meaning or include all three dimensions of human rights obligations. Yet, nothing in the treaty supports the view that the parties intended to deviate from the generally accepted three-dimensional set of human rights obligations. Therefore, it can be argued that ‘uphold’ should be interpreted to mean ‘respect, protect and fulfil’ human rights.

Finally, it needs to be clarified what the treaty means with the reference to ‘human rights in the host state’. Does this refer to those human rights which are applicable in the host state as a matter of domestic and international law, or does it refer to all international human rights? A contextual interpretation of that clause taking paragraph 4 of Article 18 into account would suggest that at least those human rights treaties which are binding on the two state parties would be included. In addition, one could argue that as investors are obliged to follow domestic law, human rights in Article 18 para 2 of the BIT refer to those human rights which are part of the domestic law of the host state.

It has been suggested that the approach taken by Morocco and Nigeria in their BIT is part of an emerging trend in African investment treaty practice and law-making.Footnote 51 For example, Article 14(2) of the Supplementary Act on Investment of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) of 2009 holds: ‘Investors shall uphold human rights in the workplace and the community in which they are located. Investors shall not undertake or cause to be undertaken, acts that breach such human rights. Investors shall not manage or operate the investments in a manner that circumvents human rights obligations, labour standards as well as regional environmental and social obligations, to which the host State and/or home State are Parties’.Footnote 52 Similarly, Article 19 of the African Union’s Draft Pan-African Investment Code (PAIC) of 2016Footnote 53 states ‘Investments shall meet national and internationally accepted standards of corporate governance for the sector involved, in particular for transparency and accounting practices.’Footnote 54

Yet, despite these models, no other bilateral investment agreement or agreement with investment protection followed the approach taken by the Morocco–Nigeria BIT so far. In fact, Morocco and Nigeria themselves have not been pursuing the idea of investor obligations further: the Brazil–Morocco BIT signed on 13 June 2019 follows the Brazilian model BITFootnote 55 and the Morocco–Republic of Congo BIT signed more than a year after the Nigeria–Morocco BIT in April 2018 does not contain any reference to investor obligations or corporate social responsibility standards.Footnote 56 Nigeria has not signed any investment agreement since the signature of the Morocco–Nigeria BIT.Footnote 57 The Nigeria–Singapore BIT signed in 2016 shortly before the Morocco–Nigeria BIT contains no investor responsibilities either.Footnote 58

However, a related approach can be found in Article 18(1) of the 2019 Model BIT of Belgium and Luxembourg.Footnote 59 It requires investors to ‘act in accordance with internationally accepted standards applicable to foreign investors to which the Contracting Parties are a party’. Internationally accepted standards applicable to foreign investors would seem to refer to such regimes as the UNGPs, the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises or the ILO Tripartite Declaration of Principles concerning Multinational Enterprises and Social Policy. These standards would fall into the ambit of the clause if the parties of the investment treaty would also be a ‘party’ to that standard. Technically though, as these standards do not constitute international treaties, they have no parties. However, the term ‘party’ should not be interpreted in such a strict technical manner. It seems to refer to the Member States of the relevant international organization which adopted the standard (UN, ILO and OECD) and in the case of the OECD Guidelines also to the additional 12 adhering non-OECD countries. The legal effect of a provision like Article 18(1) of the Model BIT would therefore be that voluntary, non-binding standards of conduct would be turned into legally binding norms. In short, investors would be bound by the duties enshrined in these standards.

2. Best Endeavour and Soft Law Approaches

The previous section showed that it is possible to include direct investor obligations in investment agreements, but states have been reluctant to implement such an approach in practice. Instead, most agreements that contain references to investor obligations employ non-binding standards including best endeavour-obligations or other hortatory language. One leading example is Article 14(2)(b) of the 2015 Brazilian Model Cooperation and Facilitation Investment Agreement.Footnote 60 It reads: ‘The investors and their investment shall endeavour to comply with the following voluntary principles and standards for a responsible business conduct and consistent with the laws adopted by the Host State receiving the investment […] (b) Respect the internationally recognized human rights of those involved in the companies’ activities […].’ Brazil has included this clause in most of its recent investment agreements.Footnote 61

The clause is noteworthy for a number of reasons. First, it is important to realize that the clause construes a binding obligation (‘shall’). However, the content of that obligation is limited to the best endeavour of an investor to comply with what the clause calls ‘voluntary principles and standards for a responsible business conduct’. While the clause therefore considers the standards as ‘voluntary’, it requires investors to at least attempt to comply with these standards. In other words, an investor that ignores these standards at all or even openly rejects them would violate this obligation. However, any failure to actually comply with the standards would not be a violation of the agreement as long as the investor can demonstrate that it tried to achieve the standard. Nevertheless, the Brazilian approach may be a step towards more binding obligations, because it is not completely within the discretion of the investor to respect human rights.

Furthermore, the clause in the Brazilian Model BIT also raises questions concerning the term ‘the following voluntary principles and standards’. It is not clear what this term refers to, because the clause does not mention any specific principles and standards such as the UNGPs or the OECD Guidelines. It must be assumed that the various broad and general conduct standards listed in letters (a) to (k) of Article 14 paragraph 2 are the mentioned principles and standards.Footnote 62 Yet, it should be pointed out that not all of those standards are merely ‘voluntary’. For example, human rights as mentioned in Article 14 paragraph 2 letter (b) cannot be reduced to non-binding voluntary standards, because the UNGPs contain binding obligations for states and a strong normative expectation for business to adhere to the standards of corporate human rights responsibility.Footnote 63

While the Brazilian approach requires investors to attempt to comply with international standards, many other investment agreements use softer language. Often, the parties suggest that investors ‘should’ adhere to international standards or incorporate such standards into their business models.Footnote 64 For example, Article 12 of the Argentina–Qatar BIT of 2016 states ‘[i]nvestors operating in the territory of the host Contracting Party should make efforts to voluntarily incorporate internationally recognized standards of corporate social responsibility into their business policies and practices.’Footnote 65

Similarly, Article 24 of the African Union’s Draft Pan-African Investment Code (PAIC) of 2016Footnote 66 requires that ‘the following principles should govern compliance by investors with business ethics and human rights: (a) support and respect the protection of internationally recognized human rights; (b) ensure that they are not complicit in human rights abuses; […].’ The development of investment law in Africa is still ongoingFootnote 67 and it is possible that a future Investment Protocol of the African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA) may contain stronger obligations.Footnote 68

An even less strict and indirect approach does not contain direct encouragements or soft expectations of investors but requires the state parties to encourage them. Examples can be found in Article 7(2) of the 2019 Model BIT of the NetherlandsFootnote 69 and Article 5 paragraph 2 of Chapter 9 of the Pacific Agreement on Closer Economic Relations (PACER) Plus of 2017Footnote 70: ‘The Parties reaffirm the importance of each Party encouraging enterprises operating within its territory or subject to its jurisdiction to voluntarily incorporate into their internal policies internationally recognised standards, guidelines and principles of corporate social responsibility that have been endorsed or are supported by that Party.’ This clause only indirectly addresses investors, because it requires each state party to act first. Hence, the ‘encouragement’ will only materialize if and when the respective state party actually acts upon it.

The difference between a direct encouragement in the investment agreement and a reference to the obligation of the parties to encourage investors to adhere to standards of corporate responsibility may seem marginal from a substantive perspective. However, it could become relevant if applied in a concrete investor–state dispute: a tribunal which would consider the activities and the behaviour of the investor in the context of applying the investment agreement might find it easier to assess the investor’s behaviour on the basis of the respective standards if they are part of the agreement itself. If the investment agreement only refers to the state party’s obligation, the tribunal might have to assess first if the state party adopted a policy of encouraging the relevant standards.

3. Obligations to Observe Host State Laws and Regulations

Apart from creating direct legal obligations or incorporating soft law approaches, investment treaties can also contain obligations of investors to comply with the domestic law of the host state. Even though this requirement may seem redundant, because investors are bound by the laws of the host state in any case, it incorporates the respective obligations into the international legal relationship between investor and host state. This strengthens the obligations and could turn a violation of domestic law into an issue subject to a potential investor–state dispute. The requirement to observe domestic law functions therefore in a similar way as an umbrella clause in international investment agreements which incorporates domestic rights of the investor into the international investor–state relationship.

Sometimes, the reference to domestic law is linked to the idea of human rights. For example, Article 12.1 of the Indian Model BIT states that ‘[i]nvestors and their Investments shall be subject to and comply with the Law of the Host States. This includes, but is not limited to, […] (v) Law relating to human rights.’Footnote 71 Similarly, Article 7(1) of the 2019 Model BIT of the NetherlandsFootnote 72 holds that ‘[i]nvestors and their investments shall comply with domestic laws and regulations of the host state, including laws and regulations on human rights, environmental protection and labor laws.’

It is clear that provisions like these do not establish a direct obligation of investors to adhere to international human rights law. Instead, the extent of the human rights obligations will be determined by the legislator of the host state.Footnote 73 Hence, the scope and contents of those obligations would vary. It could be argued that the laws of the host state would include the legislative act incorporating human treaties into the domestic legal order in dualist systems. In this case, a reference to domestic law would also refer to international human rights treaties. However, such a reference could also be interpreted to refer to domestic legislation that is aimed at implementing human rights obligations into domestic law. While some states incorporate international human rights treaties into their constitutional law, others include catalogues of specific human or basic rights in their constitutions. Yet, even if human rights are part of the domestic law, they do not necessarily contain binding obligations on non-state entities. Like international human rights law, domestic human rights are often only binding on public entities. In these cases, it could be argued that provisions like the ones mentioned above refer to those elements of domestic law which aim at the protection of human rights even if they do not mention human rights specifically. For example, setting quality standards for drinking water protects the human right to health and to water specifically, even if the respective legislation is not formulated in the language of human rights. Similarly, the adoption of labour rights, wage laws and safety standards at work implement the rights associated with the human right to work.

However, even if the reference to domestic ‘laws on human rights’ is understood in such a broad manner, it is unclear how it relates to the general obligation of investors to adhere to relevant and applicable domestic legislation. Again, as investors are typically bound by all domestic laws of the host state, it could be asked if the reference to human rights has any added value. In any event, such a reference does not create any new substantive obligation of investors. Nevertheless, a reference to domestic laws and legislations in an investment treatment incorporates them into the international investment law realm may become relevant in a concrete dispute. The state could argue that the investor is also bound by domestic laws as a matter of international law and that this should be recognized by a tribunal assessing a concrete case.

4. Consistency of Investment Treaty-Making and Human Rights Treaty-Making

It should be clear from the above that states remain reluctant to include direct investor obligations in investment agreements, despite some interesting developments in newer model agreements. The academic and political attention to the approach taken by the Morocco–Nigeria BIT seems to over-estimate the willingness of the states to include binding obligations. States apparently fear that such obligations would deter investors and therefore defeat the purpose of an investment agreement which is aimed at attracting investors even if the empirical basis for assuming that investment agreements contribute to the flow of investment is questionable. Nevertheless, states increasingly address investor obligations by either incorporating best endeavour standards or references to soft law standards. This approach coincides with the reluctance of states to create binding obligations for business entities in the human rights realm.Footnote 74 It is not surprising that states which are not even willing and able to incorporate binding business obligations in human rights treaties are reluctant to include binding investor obligations in investment agreements, especially as these are predominantly aimed at granting rights to investors. Both the investment regime and the human rights regime seem to rely predominantly on non-binding standards for investors and not on binding obligations. When it comes to binding obligations, both regimes focus on what states could and should do. However, while investment agreements typically only incorporate the obligation of investors to adhere to the laws and regulations of the host state, human rights agreements can also include obligations of home states such as the obligation to adopt binding human rights due diligence regulations.Footnote 75

B. Human Rights Obligations of Investors Established by Investment Tribunals

As demonstrated above, attempts to establish express obligations for business entities in international treaties have not been successful so far. This is one of the reasons why a lot of attention has been given to developments in international investment arbitration.Footnote 76 Human rights can be relevant in an investment dispute in a variety of different settings: investors themselves can claim human rights, states can rely on human rights as justifications for regulatory activities, or investors can be held responsible for violating human rights of the population of the host state.Footnote 77 The latter constellation is of special interest in the current context as it could be the scenario in which investment tribunals would be able to develop obligations of investors.

At the outset, it should be realized that investment tribunals would typically only be given the opportunity to discuss human rights obligations of investors if the responding state refers to them either by arguing that the investor is not eligible for the protection of the investment agreement because it violated human rights (the ‘clean hands’ doctrineFootnote 78) or by raising counter-claims to the extent this is possible. Unless states introduce these arguments or claims, an investment tribunal would not assess any possible obligations of investors, because the scope of the analysis of a tribunal is usually defined and limited by what the parties argue, and which claims they make. In this context, it is worth noting that states have generally been reluctant to raise such counter-claims in investment arbitration proceedings.Footnote 79

Generally, investor obligations could be developed by investment tribunals on three legal grounds. First, tribunals could use references to other applicable law in an investment treaty and develop obligations based on human rights treaties or general international human rights law applicable between the parties of the investment agreement. This approach was adopted by the Urbaser tribunal.Footnote 80 Second, an investment tribunal could incorporate human rights obligations of investors as part of an interpretation and application of certain provisions of the investment treaty. Evidence of this method can be found in the Separate Opinion in Bear Creek. Footnote 81 Third, tribunals could rely on specific references to human rights obligations in the applicable investment agreement. However, as seen above, so far investment agreements do not include specific human rights obligations of investors, which means that tribunals would have no reliable basis in the language of the agreements. As a consequence, they might have to rely on other clauses containing investor obligations. This was hinted at in the Aven dispute.Footnote 82

1. Human Rights Obligations of Investors as Part of General Human Rights Law: Urbaser v Argentina

The first investment tribunal which accepted the idea that investors have human rights obligations was the ICSID tribunal in the matter of Urbaser v Argentina which rendered its award on 8 December 2016.Footnote 83 The case concerned a concession for water and sewage services granted to a company established by Urbaser. During the Argentinian financial crisis between 1998 and 2001, the project ran into difficulties and the concession was terminated.Footnote 84 Unlike in previous cases in which Argentina – although reluctantly – referred to its obligations under human rights law, especially the right to water, to defend its measures,Footnote 85 Argentina filed a counterclaim in Urbaser based on the investor’s alleged failure to provide the necessary investment into the water concession. According to Argentina this constituted a violation of the investor’s ‘commitments and its obligations under international law based on the human right to water’.Footnote 86

After determining that the claim fell within its jurisdiction, the tribunal held that international human rights were part of the applicable law in the dispute because the relevant BIT included a reference to ‘general principles of international law’.Footnote 87 The tribunal therefore developed its arguments on the basis of general human rights law and not on the specifics of the applicable investment treaty which did not expressly refer to any investor obligations or standards of corporate social responsibility.Footnote 88

The tribunal began its reasoning by stating that the existence of human rights obligations of investors could not be categorically dismissed based on the fact that they are not subjects of international law.Footnote 89 Indeed, the existence of investment treaties indicates that corporations can be partial subjects of public international law. However, this does not establish which obligations they have. The tribunal therefore based its finding on the growing importance of corporate social responsibility standards.Footnote 90 Acknowledging that those standards alone cannot provide a legal basis for human rights obligations of private companies, the tribunal turned to international human rights instruments. The tribunal’s first argument concerned the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), in particular Article 30 of the UDHR, which provides that the UDHR may not be interpreted as allowing a state, group or person to destroy the rights and freedoms enshrined therein. According to the tribunal, this provision indicates that private entities can also be bound by human rights in general.Footnote 91 The tribunal also pointed to Article 5 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), which is comparable to Article 30 of the UDHR.Footnote 92 The tribunal concluded that these provisions show that the right of an individual is complemented by an obligation by public and private entities ‘not to engage in an activity which is aimed at destroying those rights’.Footnote 93

Concerning the specific question of whether the claimant was bound by an international law obligation to provide the people living in the area of the concession with drinking water and sanitation services, the tribunal pointed out that the contractual obligation of Urbaser to provide water based on the concession would not include an international legal obligation of the investor.Footnote 94 The tribunal also recalled the state’s obligations in the context of the human right to water which ‘entails an obligation of compliance on the part of the State, but it does not contain an obligation for performance on part of any company providing the contractually required service’.Footnote 95 Arguing that investor obligations would have to be distinct from the State’s responsibility to serve its population with drinking water and sewage services, the tribunal held that Urbaser was not under such an obligation and therefore dismissed the counter-claim.

The determination of the tribunal and its legal reasoning have already led to number of academic comments. Some have questioned the doctrinal support for the broad claims concerning the idea of human rights obligations of corporations,Footnote 96 while others have argued that the practical impact of the approach taken by the tribunal may be minimal because the standards set by it for an investor’s duty to actually perform certain services or activities to discharge human rights obligations will usually not be met.Footnote 97 Nevertheless, it has also been pointed out that the tribunal’s approach may lead the way to future cases in which investors could be held liable for violations of human rights.Footnote 98

Regardless of its imminent practical impact, the tribunal’s approach raises important conceptual questions. In particular, the tribunal’s interpretation of Article 30 of the UDHR and Article 5 of the ICCPR is not based on the conventional understanding of human rights. Both provisions can be used as context when interpreting specific clauses of the human rights instruments, but they do not address the question of potential duty-bearers under the relevant international instruments.Footnote 99 To substantiate the claim that the UDHR ‘may also address multinational companies’, the tribunal referred to an article by Louis Henkin,Footnote 100 who argued that the UDHR applies to everyone. Henkin relied on an the Preamble of the UDHR which states that ‘every individual and every organ of society, […] shall strive […] by progressive measures, national and international, to secure their universal and effective recognition and observance’.Footnote 101 Apart from the question if a Preamble can establish any binding effects, it is also doubtful if this sentence creates a binding obligation of individuals and companies to human rights as it only refers to an obligation to ‘strive […] to secure universal and effective recognition and observance’.Footnote 102 Furthermore, the tribunal provides no reference to existing standards of interpretation (textual, contextual or object and purpose of human rights treaties) nor does it suggest any case law which might lead into the direction of human rights obligations for private entities. The tribunal could, for example, have asked if the existence of international standards and domestic laws on corporate responsibility leads to customary investor obligations.

While many human rights activists and critics of the current system of international law may welcome the fact that an investment tribunal held that investors are – at least in principle – bound by human rights obligations, the reasoning in Urbaser is more problematic than it seems. The tribunal not only erroneously held that Article 30 of the UDHR and Article 5 of the ICCPR contain a legal basis of human rights obligations of individuals and companies, it also made some confusing statements about the content of the right to water. It is unclear if the tribunal reduced the right to water to the dimension of the duty to fulfil as it pointed out that it is the state’s duty to ‘serve its population with drinking water’.Footnote 103 Furthermore, the assertion that a state is obliged to provide the citizen with water while the investor is not, suggests that the human rights obligations of investors are different from the state obligations. Yet, if there is a human right obligation to provide water to the citizens and if the investor is bound by human rights it is not convincing that the investor would not be bound by such an obligation as well. In sum, the tribunal’s reasoning does not reflect the current state of human rights law. So far, there have been no other arbitral awards following the idea of investor obligations based on the Urbaser approach.Footnote 104

2. Respecting Human Rights as Obligation to Reduce Damage: Separate Opinion of Philippe Sands in Bear Creek v Peru

Another approach to develop human rights obligations relevant in an investment case was adopted in the separate opinion of Philippe Sands in Bear Creek v Peru of 30 November 2017.Footnote 105 The case concerned a Canadian mining company seeking to invest in a Peruvian silver mine. The tribunal unanimously decided that Peru’s revocation of a previously granted permit necessary to operate the mine amounted to an indirect expropriation. The tribunal therefore awarded Bear Creek compensation for its respective losses.

However, arbitrator Philippe Sands was of the opinion that certain activities of the investor, especially its role in causing social unrest in the area of the project, should have been taken into account when calculating the amount of the compensation. Sands referred to ILO Convention No. 169 concerning Indigenous and Tribal Peoples in Independent Countries, which is generally accepted as part of human rights law.Footnote 106 Sands conceded that the obligation to implement ILO Convention 169 falls on states and not on private parties. Yet, he also stated that ‘the fact that the Convention may not impose obligations directly on a private foreign investor as such does not, however, mean that it is without significance or legal effects for them’. This statement is associated with a specific reference to the Urbaser tribunal.Footnote 107 Sands went on to argue that ILO Convention 169 was applicable in the case at hand and that the investor was obliged to adhere to the requirements enshrined in that convention. Adhering to those rules would in turn have also reduced its own damage.Footnote 108 As the investor had not obtained a ‘social licence’ to operate by consulting and cooperating with the indigenous peoples affected by the project, it contributed to the failure of the project according to Sands.Footnote 109

While relying on the reasoning of the Urbaser tribunal, the separate opinion of Philippe Sands does not seem to share the conclusion that private parties could have direct obligations based on human rights law. Instead, Sands argues that investors are obliged to adhere to human rights in particular, in order to minimize any potential damages which the investors could suffer. This approach seems less burdensome on investors but may prove more powerful than the Urbaser approach due to its practical effects. First, the approach taken by Sands does not require the responding state to actually file a counter-claim. Instead it would be sufficient for the state to allege that the investor did not adhere to the requirements of international human rights law. Second, taking human rights violations of an investor into account when determining the amount of the damages could have a potentially larger effect on investors than theoretical speculations about the nature of their human rights obligations, because the reduction of damages could have direct effects on investor behaviour.

However, it should also be noted that the assessment of the conduct of an investor would be better suited in the merits part of an award and less so as part of the calculation of the damages. Yet, in the absence of enforceable obligations of the investor enshrined in the investment agreement, the damages stage may be the only opportunity to assess the conduct of the investor in this regard.

3. Investors’ Obligations Based on Host State Regulations or erga omnes Norms: Aven v Costa Rica

The second tribunal decision which referred to the Urbaser approach was the award in David R Aven and Others v Costa Rica of 18 September 2018, a case based on the investment chapter in the Dominican Republic–Central America Free Trade Agreement (DR-CAFTA).Footnote 110 The case concerned a number of investors who intended to develop a tourism project in Costa Rica which was terminated by the government of Costa Rica because of environmental problems of the project. After the oral hearings, Costa Rica filed a counter-claim against the investors arguing that they violated certain environmental regulations which were part of the laws of the host state.

After establishing its jurisdiction on the counter-claim, the tribunal first addressed the question of whether investors could have obligations in international (investment) law. Citing Urbaser, the Aven tribunal also stated that investors could become subjects of international law. It then argued that this is particularly the case ‘when it comes to rights and obligations that are the concern of all States, as it happens in the protection of the environment.’Footnote 111 In this context the tribunal referred to the idea of erga omnes norms, i.e., norms that contain rights and obligations of all states. Next, the tribunal recalled the provisions of DR-CAFTA, which required investors to abide by and comply with the measures taken by the host State to protect the environment. Based on this the tribunal stated: ‘There are no substantive reasons to exempt foreign investor of the scope of claims for breaching obligations under Article 10 Section A DR-CAFTA, particularly in the field of environmental law.’Footnote 112

Yet, the tribunal did not assess the counter-claim further based on formal reasons. The tribunal pointed out that the applicable arbitration rules required Costa Rica to specify its claims. However, Costa Rica only made a general reference to environmental damages in the project site and attributed them to activities of the investors. Costa Rica also failed to suggest facts supporting the claims and did not specify the relief sought. As a consequence, the tribunal dismissed the counter-claim without making any further comments on investor obligations.Footnote 113

In light of the procedural ‘way-out’, the tribunal did not discuss the legal basis for investor obligations further. Based on the tribunal’s arguments, two interpretations are possible: either the tribunal derives investor obligations from all erga omnes norms because they are binding on all subjects of international law, or the tribunal refers to the obligations of investors under domestic law. While the approach using erga omnes norms would only cover very fundamental human rights such as the prohibition of torture and slavery or other fundamental human rights to the extent they are part of jus cogens, the approach taking domestic law into consideration would not establish any independent obligations of investors.

4. Human Rights Jurisprudence of Investment Tribunals: A Nightmare or a Noble Dream?

Applying the allegory of the nightmare and the noble dream to the reasoning of the investment tribunals discussed above does not seem to stretch the reference to Hart too far. Investment lawyers have long accepted that tribunals enjoy a wide margin of discretion when applying broad treaty terms such as ‘fair and equitable treatment’ or ‘tantamount to an expropriation’. Yet, when does a tribunal step over the fine line between treaty interpretation and a ‘legally uncontrolled act of law making’?Footnote 114 Many investment lawyers and conventional legal scholars would probably argue that when the Urbaser tribunal decided that human rights would also include obligations for investors it crossed this line and engaged in law-making. The arbitrators sitting on the tribunal would of course rebut such claims and argue that they were applying the applicable law to the case and nothing else.Footnote 115

In light of the different approaches of Urbaser, the separate opinion in Bear Creek and Aven, it is currently unclear and unpredictable if and how tribunals will revisit the question of investors’ obligations. It also seems problematic if investment tribunals develop new interpretations of human rights law in this context which are not compatible with the jurisprudence of the regional human rights courts or the jurisprudence of the treaty bodies established in international human rights conventions. In fact, many observers are of the view that the international investment regime is not the appropriate forum to apply human rights and to further develop the idea of human rights obligations of investors, because arbitrators may not have sufficient expertise or because investment treaties only allow limited reference to human rights. This is why it has been argued that an investment tribunal which hears cases involving human rights violations should include arbitrators with experience in human rights or should allow amicus curiae providing the necessary knowledge.

This leads to the question of whether treaty reforms might not be the better way to establish such obligations. Based on clear treaty obligations such as the ones contained in the new Morocco–Nigeria BIT, investment tribunals could interpret and apply existing treaty provisions and not engage in legally uncontrolled acts of law-making. However, this would require that such obligations are established in a sufficiently clear and precise manner. Yet, as seen above, a mere reference to human rights is not sufficient. Indeed, the current state of investment treaties and the proposed treaty on business and human rights do not seem to provide the necessary level of precision and clarity.

V. Moving Forward and Conclusion: Neither Nightmare nor Noble Dream – Towards a Pluralistic Law of Investor and Business Obligations Concerning Human Rights

The preceding analysis reveals a sobering result: it cannot be assumed that a new human rights treaty will contain directly binding obligations for business entities. Similarly, recent treaty-making practice in investment law also does not seem to move towards including clear and precise binding human rights obligations for investors. Finally, investment tribunals remain extremely reluctant to develop such obligations on the basis of existing international law. If they consider such approaches, the doctrinal basis is not clear. As a consequence, it seems unlikely that investor obligations to respect human rights will emerge in the foreseeable future in international treaty-making or treaty-application. For the time being, international human rights lawyers and international investment lawyers will have to accept that the noble dream of courts and tribunals applying clear, precise and comprehensive international obligations of investors will not become reality. This may be disappointing to observers who hoped that investor obligations at the international level would bypass the lacunae of domestic legislation and the gaps in its application.

However, a short cut leaving the domestic laws aside is not in sight and may not even be the most appropriate approach. Instead, human rights treaties and investment agreements should focus more on domestic legislation, such as the recently adopted human rights due diligence laws in the UK (Modern Slavery Act), France (Loi de Vigilance) and the Netherlands (Wet Zorplicht Kinderarbeid). In this context, it is interesting to note that the Revised Draft of a Legally Binding Instrument for Business and Human Rights contains obligations of states to regulate businesses in the interest of protecting human rights.Footnote 116 At the same time, investment treaties incorporate references to domestic laws and may even oblige the states to effectively regulate businesses in a domestic and international setting. If relevant domestic laws are then incorporated into an investment treaty with the aim to allow a state to either base a counter-claim on the non-compliance of a domestic law by the investor or use such non-compliance to reduce the amount of the damages, international investment law and tribunals may indirectly contribute to the establishment of human rights obligations of investors. Finally, states should increasingly refer to international standards of investor responsibilities in their investment treaties. This would the allow investment tribunals to rely on standards such as the UNGPs or the OECD Guidelines when interpreting and applying the terms of investment agreements.

The emerging pluralistic regime of investor obligations consisting of domestic legislation, international soft law standards and binding international treaty norms could form the basis of a web of clear and effective provisions establishing investor responsibilities on safe legal grounds. Whether such a regime contributes to a process of global constitutionalizationFootnote 117 remains to be seen. From a more practical perspective, it may nevertheless lead to more corporate accountability while sparing us nightmares of unclear legal developments in the future, and bringing us closer to a noble dream of a fair regulation of corporate accountability.