I. Introduction

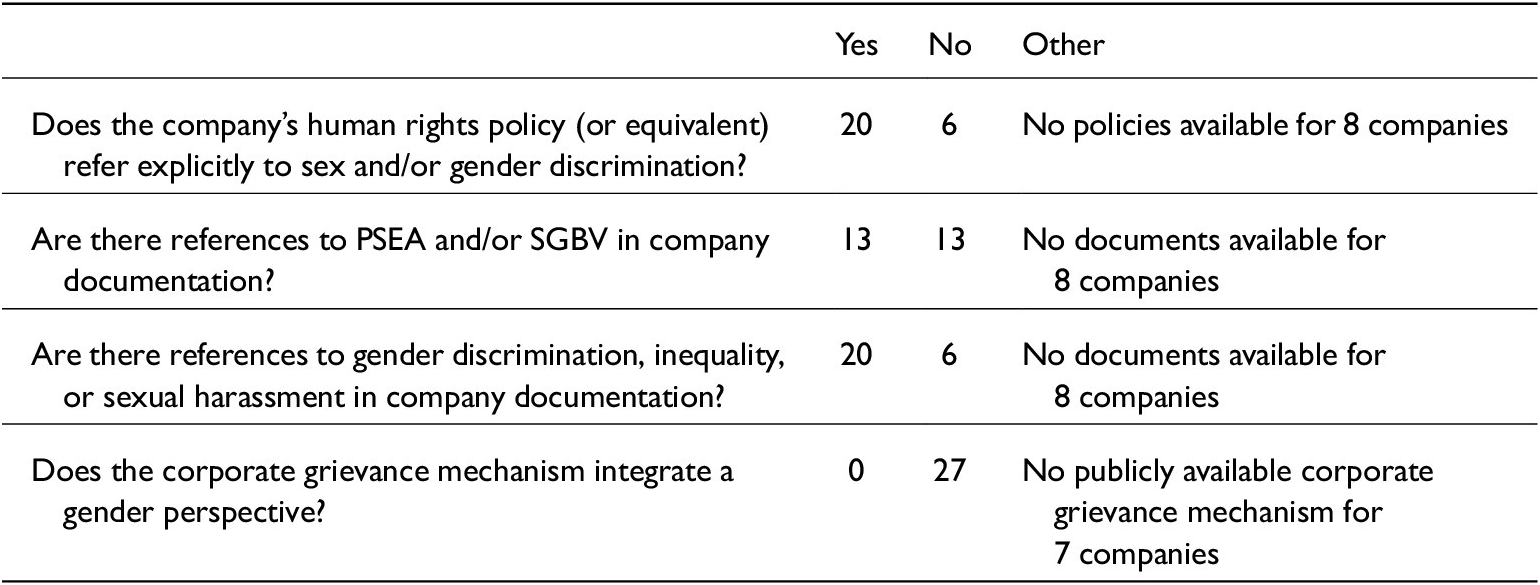

It is well documented that the private military and security industry has the capacity to do great gendered harms to both those it encounters and those it employs.Footnote 1 Significantly, it is also a sector where a variety of human rights-based approaches, instruments and mechanisms have emerged beyond the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs).Footnote 2 The International Code of Conduct for Private Security Providers (ICoC) addresses gender, and sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV), and explicitly requires private military and security companies (PMSCs) to integrate a gender perspective in their practices.Footnote 3 Through an examination of publicly available documents and policies required for PMSCs certified as complying with the ICoC, this piece evaluates whether PMSCs do in fact integrate a gender perspective into their human rights policies and grievance procedures (see Table 1).Footnote 4 Our study of certified PMSCs demonstrates that despite increased attention to the potential for negative gender impacts in the sector, companies have not developed gender-responsive policies and procedures. It can be said, therefore, that gender is not addressed in any meaningful way by PMSCs. More specifically, we conclude that PMSCs have not yet shown the required holistic understanding of gendered impacts and barriers that is required to respect human rights, and that further efforts are needed in the sector.

Table 1. Mapping ICoCA Certified Companies: Gender References in Publicly Available Corporate Materials

II. Recent Developments

In 2019, the United Nations (UN) Working Group on the use of mercenaries (of which one of the authors is a member) issued a report highlighting the widespread gendered human rights impacts of PMSCs, including SGBV, and urging the promotion of ‘substantive equality and gender-mainstreaming’ within the industry.Footnote 5 It concluded that PMSCs, as well as states and other clients of PMSC services, were failing to ensure gender-responsive approaches to data-gathering, monitoring, due diligence, accountability and remedies.Footnote 6

More recently, the International Code of Conduct Association (ICoCA), the multi-stakeholder body tasked with the governance and oversight of the ICoC,Footnote 7 published guidance on Preventing and Addressing Sexual Exploitation and Abuse (PSEA).Footnote 8 The guidance aims to ensure that ICoCA members comply ‘with the obligations that derive from Paragraph 38’ of the ICoC on PSEA and SGBV and to ‘mitigate the risk of SEA effectively, and address incidents and allegations.’Footnote 9 In addition, references to the Women in Peace and Security (WPS) agendaFootnote 10 surfaced in discussions at ICoCA’s 2020 Annual General Assembly and a focused webinar.Footnote 11

Importantly, PMSC members of ICoCA are required to meet human rights standards. In order to obtain ICoCA certification to the ICoC, companies are audited by a third-party Certification Body to certain management standards recognized by ICoCA.Footnote 12 At present ICoCA recognizes ANSI/ASIS PSC.1‑2012Footnote 13 and ISO 18788‑2015,Footnote 14 for land-based security providers, and ISO 28007‑1:2015Footnote 15 for maritime security providers, as standards that partially meet the requirements of the Code. Upon receiving certification to one of the standards, the company must thereafter satisfy additional requirements set by ICoCA to fully comply with the ICoC.Footnote 16

Therefore, a wealth of detail exists on what is expected from PMSCs when integrating international human rights standards. In practice, implementation of human rights norms, including those on gender equality and non-discrimination, is poor. Specific attention to gender and SGBV within the private security industry is urgently necessary: (1) to avoid and address documented adverse gendered impacts in the sector; (2) to implement the 2019 recommendations of the UN Working Group on the use of mercenaries; and (3) to support ICoCA’s efforts to improve the gender responsiveness of the industry.Footnote 17

III. Asking Gender Questions of PMSCs

While there is significant literature on PMSCs in general,Footnote 18 information on the gender dimension of PMSCs, what happens in their operations, and information from and about companies, is scarce and opaque. Our conclusions in this piece are based on desk research, including for the UN Working Group on mercenaries’ gender reports.Footnote 19 It also draws on our observationsFootnote 20 and stakeholder engagements during the development of the ICoC and creation of ICoCA, as well as close involvement in drafting industry guidelines and policies.Footnote 21 This piece builds on Sorcha MacLeod and Rebecca DeWinter-Schmitt’s analysis of certified PMSCs, but adds the 34 companies certified by ICoCA as of January 2021 and a more explicit gender inquiry.Footnote 22 These PMSCs are chosen because their certified status indicates that they should be the most compliant ICoCA members, and as such have an exemplary role to play.

Four key elements were assessed when reviewing publicly available documentation from these companies, in an attempt to ascertain the level of PMSC engagement with, and understanding of, gendered human rights impacts:

-

1. Does the company’s human rights policy or an equivalent document (e.g., a code of conduct or code of business ethics) make explicit reference to sex and/or gender discrimination? An indirect and general reference, such as a statement signifying compliance with the ICoC while a positive indicator of intent, is not sufficiently detailed to demonstrate verifiable gender integration within company processes.

-

2. Are there references to PSEA and/or SGBV in company documentation? This is a significant question because, as highlighted above, ICoC Paragraph 38 specifically addresses PSEA and SGBV, and these issues are the focus of the new PSEA Guidance.Footnote 23

-

3. Are there references to gender-based discrimination, equality or sexual harassment in company documentation? ICoC Paragraph 42 contains a general prohibition on discrimination, and ICoC Paragraphs 64 and 65 address harassment of employees.Footnote 24

-

4. Does the corporate grievance mechanism (CGM) ‘integrate a gender perspective?’Footnote 25

By mapping the practice of these industry leaders, one gets a sense of whether progress has been made and how much remains to be done. This analysis is a first step, and deeper insight will be gained by further research on PMSC practices.

IV. Analysis

The data gathered make alarming reading. Originally, we envisaged an in-depth investigation and assessment of how PMSCs tackle gender in the context of their responsibility to respect human rights, both internally and externally, but our research design turned out to be too ambitious. We over-estimated the extent to which certified PMSCs address human rights in general, let alone from a gender perspective. In our analysis of publicly available corporate policies, we were only able to assess internal human rights impacts, due to the problems highlighted below. While external impacts may also be diminished by thorough internal action, the dearth of available information meant that we could not examine these interactions.

In numerous cases we cannot conclude whether the company engages with or understands gendered human rights impacts at a policy and procedural level, because no human rights documentation is publicly available for eight companies. No human rights policy or an equivalent is publicly available in another three cases, and although these companies do have some human-rights related documents they do not meet the various declaratory and operational elements of an effective human rights policy.Footnote 26 While a few companies have an operational-level CGM, further examination shows that many do not meet the standards of legitimacy, accessibility, predictability, equity and transparency, and in seven cases there is no mechanism in place.Footnote 27 Similar issues were identified by MacLeod and DeWinter-Schmitt in 2019 and it is extremely concerning to note that there has been little improvement since then on the human rights due diligence and remedy basics, let alone gendered impacts.Footnote 28 What is more, the problems seem to be especially prevalent in the most recently certified companies, indicating that concerns raised in previous research have not led to stronger scrutiny.

References to Gender in PMSC Human Rights Policies

Where PMSCs do address gender in their human rights policies, or equivalents, they tend to do so in two narrow and distinct ways that align with the provisions of the ICoC as highlighted above. First, the majority of companies address gender-based discrimination and unequal treatment in the workplace. Harassment, however, tends to be referred to in generalized and gender-neutral terms, thus reflecting the ICoC.Footnote 29 Second, some make explicit reference to PSEA and/or SGBV. Only 13 out of 34 companies do so, however, which is surprising given Paragraph 38 of the Code and the 2019 guidance on PSEA.

In several cases, there are general references to a commitment to or respect for human rights, or to specific instruments such as the ICoC, the UNGPsFootnote 30 and other human rights instruments, all of which mention gender. However, they fail to demonstrate how they intend to integrate provisions on gender-responsive implementation or gender-transformative remedies. In the best-case scenario, some of the policies replicate the ICoC language on discrimination, harassment and PSEA/SGBV, but they do not specifically develop them or adapt them for implementation.

Thus, the gender elements of the policies are limited, indirect and opaque, and not well understood.

Corporate Grievance Mechanisms

It is of great concern that many of the CGMs examined are not broadly human rights compliant, including in their failure to be gender responsive.Footnote 31 While some publicly available CGM procedures are detailed and use reporting platforms, many consist only of an email address, with little description or explanation of the process. Many are difficult to find, some have broken or non-existent hyperlinks, or are only available in English. This renders most of these CGMs inaccessible from the perspective of a third-party complainant with limited English or literacy. Furthermore, given the opaque nature of most of the procedures, it is hard to imagine that someone with a sensitive complaint would feel encouraged to use the channels offered, assuming they can locate them in the first place.Footnote 32

While the ICoC does not define accessibility, ICoCA guidance on grievance mechanisms aligns with UNGP Principle 31, and additionally promotes gender sensitivity.Footnote 33 For example, a CGM must be accessible in a variety of ways, and barriers to using the CGM must be reduced, such as ensuring that appropriate languages are employed and that women ‘feel comfortable’ engaging with the mechanism.Footnote 34 Similarly, PSC-1 and ISO 18788 both require that procedures ‘minimize obstacles to access caused by language, educational level, or fear of reprisal’.Footnote 35 The question arises, therefore, as to why ICoCA and certification bodies have labelled these CGMs as compliant.

While a handful of companies address barriers to accessibility that may disproportionately impact women complainants, such as the need for independent support, confidentiality, protection from retaliation or language accommodation, the majority do not. Ultimately, none of the companies analysed specifically mentions or addresses gender-based discrimination or harms in their CGMs.

V. Conclusion

Despite recent normative developments, including increased references to gender-based harms, our study of the PMSC sector leads us to conclude that PMSCs rarely address these in any meaningful way. From our analysis of human rights policies and CGMs, it appears that most companies do not pay attention to gender. Those that do, address gendered inequalities in a way that is limited, non-intersectional, and restricted to issues of internal discrimination and harassment of employees, with occasional broader mentions of human trafficking.

While more research is required on the interplay of policy, procedure and practice of these PMSCs in terms of their gender responsiveness, we contend that, in light of the availability of specific regulatory guidance in the sector, its lack of gender responsiveness is more than an oversight, but suggests blatant disregard. It appears that ICoCA certified PMSCs are not demonstrating a practical or effective understanding of what gender-sensitive policies or remedies mean, or the purpose they serve, let alone the capacity to make transformative changes. This poses serious concerns for proper and full compliance by PMSCs with human rights standards.

If the industry is to take gendered inequalities seriously, ICoCA certified members should lead on this issue, and ICoCA, states and certification bodies can and should do more to ensure compliance. Much work remains to be done to implement the recent recommendations of the UN Working Group on the use of mercenaries and ICoCA’s own best practices. In working towards such implementation, underlying industry gender biases and structural factors, such as the male-domination of the sector and the so-called ‘revolving door phenomenon’, whereby former members of public security services, who tend to be male, are contracted by PMSCs, must also be redressed.Footnote 36 Research demonstrates that engrained notions of masculinity and masculinized behaviours that prevail in the public security sector are replicated in the private sector and play out as discrimination and gendered human rights impacts.Footnote 37 It is only through taking a holistic approach to addressing the gendered impacts of the sector, that current shortcomings can be remedied.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare none.

Funding

This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant agreement No. 844999.