Introduction

Ever since the regime change of 1990, Hungarian bankers have had a major influence on macroeconomic and financial policymaking. The revolving door between business and politics led to the appointment of bankers to a long list of major policy positions, from finance minister to governor of the central bank.Footnote 1 Nevertheless, bankers also exercised their power over policymaking in a less straightforward manner: through lobbying on pertinent pieces of legislation and regulation.

From the successive “consolidations” (i.e., bailoutsFootnote 2) of banks in the early 1990s to the laissez-faire approach with regards to the proliferation of foreign exchange denominated mortgage loans in the 2000s, many policy decisions were in line with the explicit and public preferences of the banking elite (here understood as the top management of major domestic retail banks). These regulatory steps drew a fair share of criticism from both the left and right ends of the political spectrum,Footnote 3 and reinforced the long-stranding descriptions of the anomalies of economic transition in the academic literature.Footnote 4

The issue of serving banking interests vs. the public interest in financial policy came emphatically to the fore of political debates in the campaign, and subsequently in the aftermath of the 2002 elections. The opposition party Fidesz, led by former prime minister Viktor Orbán, started its transformation from a continental-type Christian democratic party to one more closely aligned with the populist Right. It is in this context that the party started using antibanking rhetoric from 2002 on. As Orbán summed it up at a campaign rally between the two rounds of the 2002 elections:

(In 1998) we entered a world, in which not big business and big finance formed a government under the disguise of a socially conscious party. We entered a world, in which, from 1998, proud citizens reclaimed their rights and strengthened their communities.Footnote 5

By the financial crisis of 2008 the “government of bankers” (bankárkormány) narrativeFootnote 6 had become a major slogan in Fidesz's political communication and the notion of state or at least regulatory capture by financial interests was routinely raised by leading opposition figures. This rhetoric also proved to be crucial in the build-up to the critical parliamentary election of 2010: Its prevalence in right-wing discourses may be due to its success in mobilizing the electorate in a climate where the global financial meltdown instigated a full-scale domestic social and economic crisis because of size of the nonperforming mortgage loans. As post-2006 governments tried to “muddle through” these emergencies, social demands for an overhaul of all of financial policy, including its aspects related to regulation and taxation, grew more intense.

The 2010 elections resulted in a sea-change in multiple aspects of public life, including those related to finance.Footnote 7 Almost all aspects of the regulation and supervision of banking experienced wide-ranging changes: most foreign currency denominated (FX) mortgage loans were converted to a Hungarian forint base, monetary policy and financial regulation were unified under the aegis of Hungarian central bank (Magyar Nemzeti Bank [MNB]), and banks were subjected to an elevated bank tax.Footnote 8 From the alleged position of state capture, banks slid into a “pariah” status in domestic political discourse in a matter of a few years. Was the antibanking rhetoric a political hyperbole—or did it translate in the post-2010 period to the policy sea-change publicized by government officials? In short: Did the preference attainment of banking interests, in fact, diminish in the wake of the critical 2010 elections?

In this article we investigate this research question related to the preference attainment of banking interests in a qualitative content analysis framework. More precisely, we examine the preference attainment of the Hungarian Banking Association (HBA), the pre-eminent interest group in banking, in order to evaluate a popular claim in Hungarian political discourse—that the “government of bankers” was deposed in 2010—with scientific methods. We address this challenge by comparing the policy influence of HBA in the government cycles ending and starting in 2010. We also investigate the policy positions and preference attainment of OTP, the largest bank in Hungary, as it does not form part of an international financial conglomerate the way all other major banks (MKB, CIB, K&H, Erste, Raiffeisen, Budapest Bank, etc.) did at the time.

For the analysis, we adopted a qualitative content analysis framework and juxtaposed the policy positions of the interest group in their formal communications with actual legislation related to the same issues. This investigation was undertaken in a multistep research design by using computer-assisted qualitative data analysis software (CAQDAS, Friese, Reference Friese2014). First, we used ATLAS.ti, one such application, to hand-code all HBA press releases and yearly reports in the relevant period (2006–14) for policy topics and positions. The second step involved a similar computer-assisted analysis of pertinent legislation. In the third step, the two sources of qualitative data were ordered according to policy issues and compared for matching policy content. This yielded a raw picture of preference attainment by the HBA in the respective periods, and therefore allowed for the evaluation of our research question regarding preference attainment and its dynamics.

Results show that the general lobbying success and preference attainment of the organization on major policy issues decreased after 2010 vis-á-vis the previous period. Nevertheless, seismic activity was already underway during the 2006–10 government cycle. As for OTP, its policy positions—and therefore preference attainment—were overwhelmingly in line with those of the HBA. These findings offer a more nuanced view of bank power over policymaking in post-communist Hungary than what is available in most popular treatments, including official government communication in the post-2010 period. In this our research fills a gap in the literature when it comes to the role of interest groups in shaping banking legislation in the Central-Eastern European region.

In what follows, we first provide an outline of the relevant political economy literature. Next, we review the literature on the measurement of policy influence. The section on data and methods provides the details of our research design aimed at gauging preference attainment by the HBA and OTP. In the next section, we analyze the content of HBA press releases and OTP positions, as well as legislative texts in order to measure the preference attainment of these actors both before and after the 2010 elections. Next, we discuss some aspects of our results within the context of the broader literature, beyond the boundaries of lobbying research, on the development of the Hungarian political economy. The conclusion draws some general lessons from the results and considers avenues for further research.

Literature review

The large-scale privatization process of formerly state-controlled retail banks in Hungary took place between 1994 and 1997.Footnote 9 As a consequence, the market share of multinational banking interest grew from 12 percent in 1993 to 61 percent in 1997.Footnote 10 As a part of this process, the mainly domestic banking elite was partially replaced by appointees of the directorates of the international financial conglomerates buying into the Hungarian market.

Subsequently, according to some commentators active in the process, the harmony of political and business interests in the financial services sector led to the “golden age” from the end of the decade through the mid-2000s.Footnote 11 In finance, the revolving door between public and private positions was in full swing,Footnote 12 which created a stable environment for launching new products and deepening financial markets since former bankers were very much in favor of policies conducive to bank profitability when they entered the government. A comparatively lax regulatory environment and a low tax burden for the sector led to a return on assets for Hungarian branches of foreign banks, which was 50 to 100 percent greater than those of corporate headquarters.Footnote 13

A significant share of high banking profitability was linked to legal contracts, which tilted the balance toward financial institutions vis-á-vis costumers—and with the full backing of the ruling coalition.Footnote 14 The outstanding loans of households to banks tripled between 2004 and 2008.Footnote 15 Signs of a potential backlash were centered around FX mortgage loans, which were the “hot” product of the 2000s.Footnote 16

As the economy suffered a downturn in the second half of the 2000s and the effects of the global financial crisis reached the semi-periphery, debt service for hundreds of thousands of costumers bypassed the nominal value of the initial loan—the share of nonperforming household loans surpassed 15 percent by 2011.Footnote 17 As eviction rates started to grow, the two socialist-backed prime ministers of the 2006–10 period, by and large proponents of the status quo, initiated mildly restrictive measures, including a code of conduct for retail lending. These measures were deemed inadequate by the larger public and—as presented in the Introduction—talks about state capture of banking interests became part of everyday political discourse from both left- and right-wing critiques of the 2002–10 governments. Events culminated in the 2010 election and the overwhelming victory of Viktor Orbán's Fidesz party, and two other parties that denounced the effectiveness of financial regulation—LMP, a green party, and Jobbik, a hard-right movement—also entered parliament.

The scales have been tipped, and from a state capture, banking interests were seemingly now relegated to pariah status. The financial policy reforms of the Hungarian government between 2010 and 2014 on the surface made good on the rhetoric the party had used during its years in opposition. Vested with a supermajority in the legislature, Fidesz initiated a complete overhaul of financial sector regulation. Major steps included a new financial special tax, several “rescue packages” for mortgage loan holders, and a comprehensive program of public utility price cuts. It is true that the thrust of these interventions was aimed at the dominantly foreign-owned banking sector. What is less clear, despite political grand-standing and the public criticism of the banking lobby of some decisions, is how these developments, in fact, affected the preference attainment of major domestic retail banks.

Preference attainment is a method to measure bank power over policymaking. As is the case with all aspects of power, bank power is a concept that withstands easy operationalization has been used for a variety of research topics as a key conceptual element from Japanese banks’ cash holdingsFootnote 18 to the influence of investment banks on the trajectory of US capitalismFootnote 19 and to German industrial development.Footnote 20 In these studies of political economy, power is presented as a relational, zero-sum notion between actors of the private economy (as in the banks had power over the boards of industrial conglomerates in twentieth century Germany). When it comes to the power of banking interests over public policymaking, this literature does not offer a clear methodological solution.

The question of bank, or financial corporate, power is also addressed, even if in a less explicit manner, in the literature on state and regulatory capture. State capture refers to “firms shaping and affecting the formulation of the rules of the game through private payments to public officials and politicians.”Footnote 21 The notion of regulatory capture is more limited in scope: it concerns particular policy areas, and it is more relevant for our purposes.Footnote 22

With the rise of illiberalism on both sides of the Atlantic, and with Viktor Orbán becoming the poster child for this ideology, references of state capture were supplanted by those related to party state capture,Footnote 23 incumbent state capture,Footnote 24 or business capture.Footnote 25 The basic idea in all abovementioned research is that corruption in public procurement and the regulation of the private economy serves the purposes of an emergent political-economic elite. As illicit funds and economic rents are channeled to governing party campaigns, the rule of incumbent parties is solidified while rentiers gain wealth and political clout.Footnote 26

Yet, once again, this literature offers little help in establishing the necessary system of measurement, if we are interested in the policy influence of a particular interest group beyond issues related to explicit rents to the lobby group in question. The good news is that, if we look beyond the literature directly referring to banking interest, a wide array of research agendas in political science and political economy addressed the question of interest group influence on policymaking in general. This is true, even as “most of the current knowledge about pressure groups is based on information from a few developed democracies like the United States, United Kingdom, and the European Union. For most of the world, there is little systematic evidence on basic questions (…) whether (pressure groups) are able to exercise any influence on policy.”Footnote 27

Of the most important research paradigms, the mainly American public choice scholarship on interest group influence can build on a favorable institutional context. Unfortunately, as Potters and Sloof (Reference Potters and Sloof1996, 413) demonstrated in their overview of empirically relevant public choice models, “studies that incorporate interest group activities other than donating to campaigns are rare.” In their more recent summary of the—mainly US—empirical scholarship on lobbying, De Figueiredo and Richter (Reference De Figueiredo and Richter2013, 29) claim that “broadly speaking there are three general classes of data typically collected on lobbying activity: surveys, registries, and transaction records.” Unfortunately, the Hungarian context offers a challenging environment for adapting this established research direction. The widely used data sources in lobbying research (such as the Encyclopedia of AssociationsFootnote 28) are either nonexistent,Footnote 29 unfeasible to collect, discontinued,Footnote 30 or yield no relevant results.

In light of these considerations, we draw on a second distinct stream in the literature, which concerns the success of organizations in exerting influenceFootnote 31 with relation to specific issues. This, mostly European, literature is more suitable for the study of transition democracies.Footnote 32 Thomas and Hrebenar (Reference Thomas and Hrebenar2008, 10) contend that interest groups had been studied in the Central Eastern European (CEE) region “but not to the same extent as political parties and elections.” In a typical study focusing on the region, Hrebenar, McBeth, and Morgan (Reference Hrebenar, McBeth and Morgan2008) present the national characteristics of the “interest system” of Lithuania based on elite interviews. Nevertheless, case studies of stand-alone policy processes and issues from the perspective of interest group influence are few and far between regarding CEE countries.

A more case-oriented research program has been evolving with respect to EU lobbying. The methodological issues of measuring interest group influence at the forefront of this line of researchFootnote 33 distinguishes “three broad approaches to measuring interest group influence: process-tracing, assessing ‘attributed influence’ and gauging the degree of preference attainment.” Of the three, the most frequently used approach has been process tracing. It maps the causal chain starting from “groups’ preferences” to “the degree to which groups’ preferences are reflected in outcomes and groups’ statements of (dis-)satisfaction with the outcome.”Footnote 34

This paradigm, however, is less adept at dealing with nonrevealed preferences and lobbying behind closed doors. The second method assesses the “attributed influence” of a lobby by conducting surveys (of the interested parties, their peers, or expertsFootnote 35). Despite its simplicity, this approach also has shortcomings, most importantly in that it only assesses the perception of influence as opposed to influence proper.

In light of these methodological difficulties, the metrics best suited for our present purposes is the “degree of preference attainment.” Here, “the outcomes of political processes are compared with the ideal points of actors.”Footnote 36 This provides a relatively clear-cut and objective metrics of policy influence, and tackles the seemingly “impossible”Footnote 37 task of measuring lobbying power.Footnote 38 For instance, Klüver (Reference Klüver2009) uses quantitative text analysis techniques to explain policy outcomes as a result of interest group activity. Her analysis is based on a comparison of interest groups’ policy positions and policy output in the given policy domain: this allows for winners and losers of the decision-making process to be designated.

Finally, Pedersen (Reference Pedersen2013) applies a complex research strategy to interest group influence on Danish parliamentary output. By combining the analysis of survey and documentary data, she is able to uncover both the informal and formal aspects of interest group influence on policymaking. Her project uses three sorts of measures: group activity, agenda-setting influence, and legislative influence. A consolidated version of these approaches could focus on the analysis of preference attainment by comparing ex ante policy positions and ex post policy outputs on the one hand, and the measurement of agenda-setting influence as a metrics of attributed influence on the other.

Data and methods

In this paper, we follow the aforementioned conventions of the literature on the winners and losers of lobbying and decision-making by examining the level of preference attainment by HBA, a major interest group in Hungarian finance. This approach allows for the exclusion of the effects of strategic communication and, therefore, provides a clearer picture when it comes to actual policy clout.

Strategic communication refers to the problem that if we consider any information provided by business lobbies beyond their policy position we may land on a slippery slope. Business groups may claim victory for strategic reasons even as their position was not in fact adopted by the government. Or, alternatively, they may overstate their potential losses whereas the policy proposal in question might not necessarily lead to such loss. In sum, in the preference attainment framework we should not consider interest group statements, which are directly related to preference attainment as interest groups may not be objective in such assessments. What we only need for such an analysis is their policy positions.

Since the methodology of gauging the influence of various actors over policymaking is not perfectly settled, innovative methods have been developed to manage this challenge. Following the conceptual framework of preference attainment by Dür and the operationalization of Klüver and Pedersen, in this paper influence is understood “as control over political outputs, such as bills or parliamentary debates.”Footnote 39 Based on these considerations, we present a case study of measuring the lobbying power of the HBA, as well as that of OTP, before and after the 2010 elections.

The HBA, an advocacy group established in 1989, is the major professional organizationFootnote 40 of Hungarian banks.Footnote 41 Its forty-eight members (as of 2018) include all major organizations in retail banking, regardless of ownership structure (foreign or domestic, corporation or savings co-operative, etc.). OTP usually retains a leadership position in HBA as a key player in the domestic market (e.g., András Becsei, the CEO of OTP Mortgage Bank, was elected as president in 2019Footnote 42). Furthermore, several government-backed institutions retain a membership from the Student Loan Centre to Garantiqua Creditguarantee Co. Our choice of HBA as a proxy for banking interests, in general, is underpinned by the fact that no similar umbrella organization exists that would cover all aspects of Hungarian retail banking.

Naturally, there might be organizations with a different business strategy approach. Furthermore, not just industry bodies may serve as proxies for banking interest as lobbying may take place on an individual, single-bank basis or in smaller groups. Regardless, the HBA generally serves as the primary conduit between the government and banking interests.

One way to look into the black box of banking interests is to differentiate by ownership structure. On the one hand, most major banks in Hungary formed part of international financial conglomerates. On the other hand, the largest balance sheet belonged to OTP, a former savings bank that had a dispersed ownership structure and management, led by CEO Sándor Csányi, which retained substantial room for maneuver. OTP, the savings bank of the socialist regime before 1990, was partially privatized in the early 1990s with IPO on the Budapest Stock Exchange, reducing government ownership to 25 percent. This was subsequently reduced to a single “golden” share.

OTP was not unique because of its sheer size or because it would be a “domestic” bank in terms of its ownership but because it did not have access to foreign exchange reserves and external capital the same way affiliated banks of international conglomerates did.Footnote 43 A key issue in this respect was the FX mortgage loan business. This product was first introduced by OTP in 2006, with a delay of a few years vis-á-vis its major competitors. By 2007, their market share was more than 60 percent.Footnote 44, Footnote 45 According to Csányi, when FX loans were first introduced, they “considered foreign currency-based loans to be risky, and I did everything to lobby against them.”

However, with the emergence of foreign currency denominated loans, the market share of Hungarian forint denominated new loans plunged and OTP reversed course. Csányi said in an interview in 2018: “How could we have avoided introducing similar products? If I had to make a decision today, I might arrive to a different conclusion, but we still delayed our market entry for a year.”Footnote 46

A further complicating factor is the complex relationship between Orbán and Csányi. Orbán partly set the goal of achieving 50 percent domestic ownership in the banking sector to “dethrone” Csányi (primarily by nationalizing and consolidating loss-making branches of foreign investors and the savings and loans sector—see DiscussionFootnote 47). But this is just one aspect of the legendarily intricate rapport between Orbán and Csányi: the OTP boss took over the Hungarian Football Association at the prime minister's personal request; the former often serves as an informal advisor to the latter; yet at the same time the two frequently take the opposing side in public debates.Footnote 48, Footnote 49, Footnote 50 Due to its unique conditions, we investigate the preference attainment of OTP in parallel with that of the HBA so that we have a better understanding of the lobbying success of banking interests

With the focus of the investigation thus set, the first step of our research design consisted of the extraction of policy positions of the lobby group and the bank as well as the selection of matching pieces of legislation. The unit of analysis in this research design was a policy issue. As for the selection of the acceptable sources of policy stances, only the official press releases, interviews, and reports were considered. This resulted in a narrower net cast for capturing policy positions than, say, an alternative that would have included news media reports. However, this approach also cut out the white noise of media processing and subjectivity in presenting the content of these official documents and communications. The idea here was that the most important issues would turn up in press releases and interviews as these are amongst the most effective tools for banks and lobby groups to disseminate their positions to the wider media.

Our first choice for documentary sources were the press releases published by the HBA as they signal the importance of an issue via the time and effort put into formulating a joint position and an investment in raising public awareness regarding the issue at hand. We used these press release texts (N = 31) obtained from the HBA website for the second period. For the first period, we resorted to yearly reports published by the HBA. The main reason for this is the retrospective discontinuation of the listing of all official HBA press releases on its website.Footnote 51 For the reports, the chapters on “professional issues” (featured in all reports) served as the basis of coding (with some exceptions).Footnote 52 Segments containing “proposals” or “initiatives” were by and large included in the database (only minor issues were dropped). For the analysis, we selected the ten most important policy issues for two periods, 2006–9 and 2010–14 (the last three months of the electoral campaign were excluded in both 2010 and 2014). This was derived from a count index of how many times specific issues were mentioned in the sources.

We also used documentary data for assessing preference attainment. Official sources of legislative activity (the text of adopted laws, or reports thereof, in papers of record) could be considered the best available sources for analyzing actual policy outputs. Document analysis provides a transparent method to analyze policy content as any potential research bias is open for scrutiny by making the underlying qualitative databases available.

Nevertheless, extracting winners and losers regarding policy issues by means of content analysis—the next step of the analysis—is far from being a straightforward task. The first obstacle is the identification of the issues in natural language texts. For this, we opted for computer-assisted hand-coding (implemented in ATLAS.ti, a qualitative data analysis software). In keeping with the basics of grounded theory, an inductive methodologyFootnote 53 that served as the guiding principle for the development of this software, issues were identified line-by-line in sources. The first, raw, list of issues was then combined into a consolidated issues codebook.

In the penultimate step, the estimated policy position of HBA was compared with the policy output for the same issue, in order to see if the explanatory variable (the ideal position of the HBA, and that of OTP) predicts policy output or not. Here a preference attainment score (“PrefScore”) was introduced, which has three values (-1, 0, 1), building on previous studies that used a binary variable.Footnote 54 As the delineation of various policy issues is a complex task, a brief narrative discussion of each PrefScore result was also provided.

Finally, a comparative analysis of the two periods in question was undertaken. Period 1 lasted from 2006 to 2009, an era of socialist-liberal, and then minority socialist government. Period 2 refers to the 2010–14 government cycle, the term of the second Orbán cabinet and the first calendar year of the third Orbán Administration. This set-up allows for the analysis of the policy outputs before and after the “treatment” of the 2010 elections and a comparative examination of the preference attainment of banking interests in two starkly different policy regimes.

Needless to say, correlation does not necessarily imply causation. Even as policy decisions by parliament and the government are in line with what banking interests lobbied for, these decisions may have been reached due to other internal (e.g., coalition discussions) or external factors (such as compliance with EU law or IMF recommendations). The inclusion of these effects in the analysis is a necessary step for establishing causation beyond correlation. This is not to say that preference attainment analysis does not have its merits: it can provide an overview of lobbying success in a complete policy subsystem over an extended period of time (something which case studies based on process tracing cannot accomplish). We return to this issue in light of our results in the Discussion section.

Analysis

The evaluation of HBA preference attainment in 2006–9

For the period 2006–9, we used HBA yearly reports to select the Top 10 major issues and to assess the ideal point of the lobby group and that of OTP with regards to these issues. As indicated above, the basic metrics of preference attainment introduced in this study is called PrefScore. PrefScore has three values: -1 stands for lobbying failure; 0 for partial success/failure; 1 for the general success of lobbying activities. For instance, resorting to legal action against a law, and losing the case in the courts, results in a value of -1. A delayed resolution of the issue or government acknowledgment of a problem without any action also falls into the partial success category. Mixed rulings by courts on complex issues also receive a PrefScore of 0. The adoption of HBA/OTP proposals without any major changes results in a PrefScore of 1.

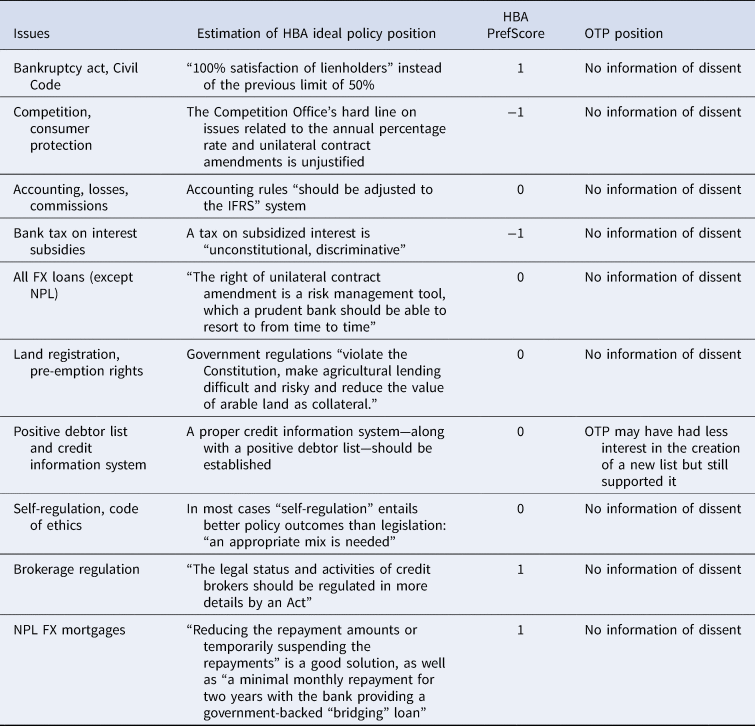

Table 1 provides an overview of the results for this period (a more detailed, individual assessment of each issue is presented below). Besides the issue description, the table displays the estimated ideal position of HBA, the metrics of preference attainment for HBA, and whether the position of OTP differed from this consensual stance. The narrative estimation of the HBA ideal policy position is based on either direct references from the coded database, or—if no adaptable reference is available—from official news agency reports and interviews with HBA representatives in established news outlets (the same applies to OTP). This second column is also indicative of the dynamic nature of policy debates: the space between the initial government proposal regarding a policy issue and the eventual solution may extend to multiple years (this point will be revisited).

Table 1. Top 10 policy issues and HBA positions (2006–9)

For each issue presented in table 1, we provide a brief discussion of the underlying policy debate and HBA preference attainment as well as potential points of conflict between subsidiaries of foreign banks and OTP. Starting with the first topic in the table, the modernization and re-codification of the Hungarian Civil Code was regarded a necessity in the 2000s,Footnote 55 resulting in the Act CXX of 2009.Footnote 56 Although this piece of legislation was never enforced, the HBA's yearly report highlights that the lobby group provided assistance throughout the legislative process.Footnote 57 There has been further cooperation on the Act XII of 2010, which amended certain financial laws based on the modified (although not in effect) Civil Code.Footnote 58 While the report made a reference to involvement in these processes, individual banks did not make public statements on the issue.

Closely tied to the Civil Code revision process was the amendment of the Bankruptcy Act.Footnote 59 This, along with other changes, gave immediate time respite to applicants in order to provide enough time for them to reach a deal with their creditors.Footnote 60 The HBA was on hand for the preparation of the draft, and their proposals regarding the creditor's mandate and cash flow related questions had also been accepted.Footnote 61 As for the crucial issue of an amendment to reinstate the previous 50 percent limit in place of the provision providing for a 100 percent satisfaction of lien holders' claims HBA reacted “firmly against” this proposal. In the end, the proposal was dropped.Footnote 62 No bank stated any special position regarding the issue.

Starting in 2007, the Hungarian Competition Authority conducted an investigation with regards to the costs of bank switching. The draft report associated with the investigation proposed a revision of rules related to the annual percentage rate (APR) and the fair exercise of unilateral contact amendments. Despite criticism from HBA, Parliament passed a bill following up on these proposals. The lobby group was “making continuous efforts to achieve” corrections to this law.Footnote 63 The official HBA response to the final report mentioned that the statement represented every member's position. Several banks contributed to the draft with data, but the final report still gave “a static and superficial picture”Footnote 64 according to the lobby group.

The Act on Accounting regulates accounting standards in the private economy.Footnote 65 The law had been enacted in 2000Footnote 66 and was amended on a yearly basis to reflect new economic realities. With regards to the issue of settlements and commissions, the European Banking Federation urged the unitary implementation of International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS).Footnote 67 The HBA supportedFootnote 68 the conversion to IFRS for multiple regulatory items,Footnote 69 which was realized in 2008. In 2017, the Head of Accounting and Financial Management at OTP Bank Group stated, that they had been ready for the implementation of the IFRS system for a decade at that point.Footnote 70 They had been making IFRS reports since 2003Footnote 71 as did many subsidiaries (see CIB Bank, an affiliate of Intesa Sanpaolo,Footnote 72 or Raiffeisen BankFootnote 73). However, the first government proposal for setting up the framework of IFRS adoption was only introduced in 2015.Footnote 74

Upon its original introduction in 2004,Footnote 75 the special bank tax was supposed to be a temporary provision aimed at increasing government revenues.Footnote 76 Subsequently, the tax base was altered: banks offering subsidized products (such as mortgage loans) were obliged to pay a 5 percent charge after interest rate subsidies.Footnote 77 According to the HBA, this new item in the tax proposal was discriminative as it selectively affected credit institutions.Footnote 78 In 2006, the then chairman of the HBA stated that the “new separate tax burden is unconstitutional and contrary to the European Competition Law.”Footnote 79 The tax was unequivocally negative for all banks, as they lost a significant portion of their yearly profit. As an analyst put it, “it damages the valuation of bank shares.” In 2005, CIB Bank lost nearly HUF 2.5 billion due to the special bank tax,Footnote 80 while in 2007, OTP had to account for a loss of HUF 6.5 billion in 2007.Footnote 81

Unilateral contract amendments were one of the main issues in both periods in question. Originally, they were bound by a code of conduct established by the banking sector, yet the opacity of contract changes provoked widespread public disapproval.Footnote 82 In late 2008, the government proposed curbing unilateral amendments.Footnote 83 According to the then chairman of HBA, these amendments were a necessary “risk management tool” of banks.Footnote 84 In the yearly report of 2009, the HBA criticized the approved modifications stating that “in multiple points, it needs serious corrections”Footnote 85 and also maintained this position in light of a study by the Competition Authority.Footnote 86 Nevertheless, even under the new rules, banks had significant leeway in modifying customer contracts. According to OTP's Media Communication Department in 2013, unilateral contract amendments “were a win-win situation until the crisis, and no one ever believed these contracts were flawed from a legal perspective.” The general criticism regarding the practice of unilateral amendments were leveled at both OTP and foreign subsidiaries.Footnote 87

The topic of land registration was crucial in the debates surrounding the regulation of mortgage loans. The land registration is a public register maintained by district offices, based on the data of the real estate register.Footnote 88 Official HBA communications made clear that changes in land laws are a sensitive issue for banks. They stated that revised government regulations make agricultural lending difficult and risky, and reduce the value of arable land as collateral. Although HBA admitted that “our motions on the other subjects were turned down, partly due to the fact that the provisions in question had in the meantime been changed during amendments to the legislation,” it realized a partial victory as the Constitutional Court struck down certain provisions of the regulations in question.Footnote 89 OTP was one of the most active banks in agricultural finance and, therefore, had a vested interest in mortgage rules as flexible as possible.

The proposal of a positive debtor list (also known as the “positive credit registry”) was aimed at a unified database that would contain the clients’ credit information in order to be more conscious of their solvency.Footnote 90 Negotiations regarding the implementation already started in 2006, however, the Hungarian Data Protection Supervisor opposed it.Footnote 91 The introduction of the system was an obligatory commitment raised by the IMF in 2008, when the country requested a loan from them.Footnote 92 It was modeled on its counterpart, the negative debtor list, which contains information of individuals with debt and that had existed in Hungary for a long time. The government started exploring the idea of a positive list in 2009,Footnote 93 and in two years the Central Credit Information System (KHR) was created (see below).Footnote 94 The HBA had been supporting the concept of establishing a positive debtor list for yearsFootnote 95 and also voiced the need for public oversight to protect the data.Footnote 96 This topic is a key case in the dynamics of preference attainment as in the pre-2010 period only preparatory steps were taken.

This is also the first issue where the initial position of OTP may have been slightly different from those of its peers. In experts interviews for a study financed by the Competition Authority, some participants shared their doubts regarding the interests of OTP in the creation of a positive list as—in its position of a dominant player—it already had access to the biggest database of costumer information and therefore retained a competitive advantage.Footnote 97 Still, as a matter of fact, in 2006, the then deputy CEO concurred that “the consolidated list could later also bring cheaper borrowing rates to good debtors”Footnote 98 and confirmed the bank's support for the new registry.Footnote 99

The topic of self-regulation and ethics was closely related to the public debates surrounding contract amendments.Footnote 100 The aforementioned government plans to re-regulate retail bank activity with the emergence of the financial crisisFootnote 101 were negatively received by the HBA. They countered this proposal with a renewed draft of the existing code of conduct in 2007, which still relied on a self-regulatory framework.Footnote 102 Nevertheless, by 2008, they voluntarily waived the unilateral introduction of certain fees and commissionsFootnote 103 and in September 2009, thirteen banks willingly signed the Code of Conduct. The creation of the code was a contentious process and Péter Felcsuti, the chair of HBA at the time, resigned over the disputes. OTP, however, was amongst the signatories, while a few smaller “foreign” banks—such as AXA—stayed away in disagreement.Footnote 104

It is within this context that a review of Act CXII of 1996, which regulated credit institutions and financial enterprises, began.Footnote 105 With the 2010 Credit Institutions Act,Footnote 106 the directives controlling financial intermediaries were radically transformed.Footnote 107 Over the years the HBA maintained an active presence in negotiations: in 2008 they initiated a more detailed statutory modification of the activities of credit intermediaries to the Ministry of Finance.Footnote 108 In 2009, they assisted on the elaboration of the rules concerning brokerages.Footnote 109 In the end, “the relevant provisions were incorporated in the amendments to the Credit Institutions Act under Act CL of 2009 amending certain financial Acts,” a lobbying success for HBA.Footnote 110

The other major issue of the pre-2010 period was non-performing loans (NPLs), which referred to a delay in scheduled payments that exceeded ninety days.Footnote 111 As a result of economic downturn, bridging loans were widely introduced in 2009,Footnote 112 targeting holders of NPL FX loans.Footnote 113 These loans had a maturity of two years and carried a government guarantee.Footnote 114 According to the HBA's annual report, “banks worked individually and with the government” on the solution. The lobby group considered “reducing the repayment amounts or temporarily suspending the repayments” to be a good enough solution, however, eventually they agreed to the creation of bridging loans as well.Footnote 115

Most banks reached this conclusion out of a necessity. For OTP, the percentage of NPLs increased from 7.5 percent to 12.5 percent in 2010. At the same time, due to restrictive eligibility criteria, the number of people entitled to bridging loans was surprisingly low.Footnote 116 Thus, banks started to offer their own debt settlement solutions and, for the time being, averted the threat of heavier regulation.

The evaluation of HBA preference attainment in 2010–14

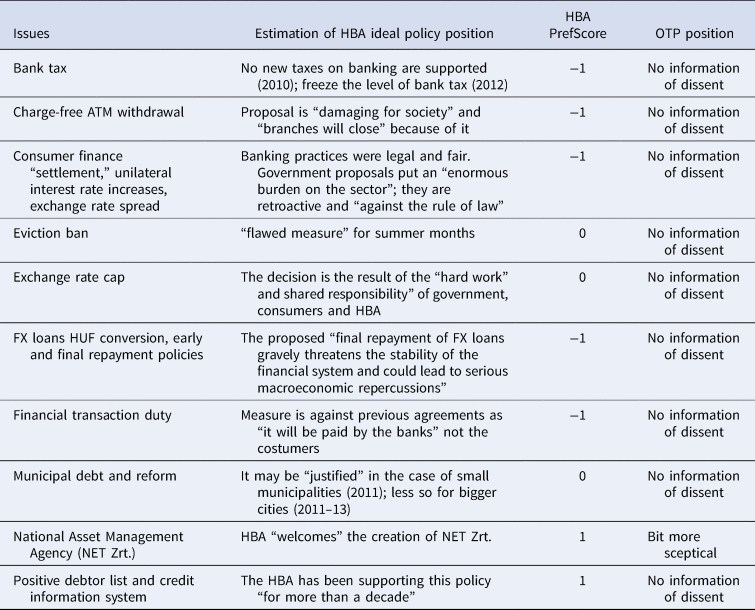

The results for the analysis of HBA preference attainment in the 2010–14 period are provided in table 2. Just as the review for the previous period, this shows a mixed picture. Of the top ten issues, five yielded a thoroughly negative result for banking interest. Two cases were in line with the ideal position of the HBA and three were associated with partial success.

Table 2. Top 10 policy issues and HBA positions (2010–14)

The bank tax (a special tax on banks, not to be conflated with the bank tax of 2006) had originally been adopted in 2010.Footnote 117 It was revised multiples times in the years to come. A key modification was enacted in 2012 when banks were able to subtract 30 percent of their loss from the sum of the tax.Footnote 118 The new duty formed part of the “Economic Action Plan,” initiated by Prime Minister Orbán in order to promote the principle of “shared responsibility.”Footnote 119 According to the HBA, the bank tax “damaged the economy as a whole.”Footnote 120 Even after multiple corrections and government sanctioned exemptions, the HBA still proposed the complete abolition of the tax in 2012.Footnote 121 In 2010 the CEO of OTP stated that he was “saddened” by the special bank tax, which was “not entirely fair” in his view.”Footnote 122

Another newly introduced levy was related to financial transactions. Bank clients with a debit card could withdraw cash from any domestic ATM for free on a monthly basis for the first two times.Footnote 123, Footnote 124, Footnote 125 According to the HBA, the regulation “damages the society,” since banks were obliged to offer a service on which they made a certain loss.Footnote 126 One of the ramifications of this initiative was the closing of multiple bank branches.Footnote 127

In 2019, Sándor Csányi stated that “. . . OTP pays the price of free cash withdrawal, with logistics, depreciation and other costs.”Footnote 128 OTP canceled several other promotional cash withdrawal services in the wake of the adoption of the proposal.Footnote 129, Footnote 130 On the one hand, OTP and Erste consumers registered for the policy most actively. On the other hand, due to the wide network of OTP ATMs, the bank incurred less out-of-bank payments than its peers.Footnote 131

A further departure from the pre-existing regulatory paradigm was enacted with the “FX loans law” in 2014.Footnote 132 This introduced new regulations with regards to the exchange rate spread applicable for loans and other issues of “banking accountability,” such as unilateral interest rate increases.Footnote 133, Footnote 134 The HBA was unequivocally opposed to the proposal, which it considered to be unconstitutional (due to, for instance, its retrospective provisions).Footnote 135 In the related lawsuit, brought against the new regulations, the HBA was also active.Footnote 136, Footnote 137 As for its part, OTP also filed (an eventually unsuccessful) complaint with the European Court of Human Rights claiming that law violated certain provisions of the European Convention on Human Rights.Footnote 138

Still related to the FX loan crisis, in 2014, the government suspended evictions for NPL-afflicted families until the summer of 2015.Footnote 139 The prolongation of the eviction moratorium had been an agenda item for quite some time by that point.Footnote 140, Footnote 141 The Banking Association's yearly report of 2013 explicitly mentioned the need for an earlier winter moratorium starting date (although as a concession in the face of public criticism of lending practices).Footnote 142 Nevertheless, in 2015, they stated that “the moratorium significantly reduced the willingness of debtors to pay,” which in general had disrupted payment discipline.Footnote 143 The Managing Director of OTP Real Estate was of the opinion that “only a small part of evictions occurs due to credit debts” whereas unpaid utility bills were a major factor. He added that generally the moratorium on eviction does not significantly affect the real estate market.Footnote 144 In sum, the partial ban was not the worse outcome for the banking lobby but not an optimal one either.

A less controversial item in the FX loans package was related to the “exchange rate cap.” This guaranteed fix repayment protection for a period of five years in the event of a major shift in foreign exchange rates.Footnote 145 Originally starting in 2011,Footnote 146 a revised scheme was introduced in 2012.Footnote 147 The HBA played a key role in the implementation of the projectFootnote 148: according to the yearly report, the construction “based on common burden-sharing between clients, the HBA, and the state.”Footnote 149 Sándor Csányi claimed that “the institution of the exchange rate cap was a very good measure. It is good for the debtors because it substantially reduces the repayment installment by almost 30 percent.”Footnote 150 This position, as well as that of the HBA at large, is best understood as the product of a hedging strategy aimed at preventing more radical measures.

In this respect it was not a success for the bank lobby, as a more long-term solution for exchange rate risk was soon provided within the framework of “FX loan conversion” initiated by the National Bank of Hungary.Footnote 151 This proposal was enacted in three consecutive pieces of legislation in 2014.Footnote 152, Footnote 153, Footnote 154 While in the yearly report concerning 2015 the HBA stated that the act of conversion was a major loss factor (amounting to HUF 30 billionFootnote 155), it also acknowledged that there had been constructive discussions between the HBA and the National Bank regarding technicalities of accounting. Despite these developments, the Banking Association was firmly opposed to the final version of the proposal.Footnote 156 Back in 2013, the CEO of OTP stated that “if all FX loans were to be converted into HUF, this would cause a total loss of HIF 950 billion to the banking sector, with a loss of 300 billion for OTP alone.”Footnote 157 In reality, in 2014, OTP registered a loss of around 170 billion.Footnote 158 Other banks experienced major difficulties due to the conversion as well, notably Erste, Raiffeisen,Footnote 159 K&H, and CIB Bank.Footnote 160

Yet another new levy on financial services was introduced with the financial transaction duty. This covered retail and corporate banking and postal transactions. The Act CVXI of 2012Footnote 161 was directly aimed at banks, which the HBA deemed to be causing the already overloaded sector to be more overwhelmed with taxation.Footnote 162 The secretary-general of HBA stated that it was up to “each banks’ own business decision” how they make up for the loss in profit, but he concluded that the laws of economics dictated that the bill will “eventually be met by consumers.”Footnote 163 After several amendment proposals and reconciliatory rounds, original duty obligations were reconstructed, yet the HBA remained opposed to this form of taxation.Footnote 164 CEO Csányi was adamant in his criticism still in 2018,Footnote 165 even as the banking sector passed 80–90 percent of the duty on to households (and even more for companiesFootnote 166).

Still related to the FX loan crisis, it was notable that by 2011, municipalities amassed more than HUF 1200 billion of debt,Footnote 167 more than 50 percent of which were FX loans with a maturity in 2011/2012.Footnote 168 The government proposed to take over this debt, but at the same time take over many functions of local governments (such as schools and administrative tasksFootnote 169). The HBA argued that “it is not necessary to restructure municipal debt” and that a “one size fits all”-type of solution was not preferred.Footnote 170 However, they agreed that “for small municipalities, the government's approach was justifiable.”Footnote 171 In the end, debt consolidation got the green light mainly in its original proposed form, although banks were obliged to pay a one-time lump sum of HUF 75 billion HUF (20 billion for OTP) as beneficiaries of the bailout.

The HBA had more success with other institutional reforms. The National Asset Management Agency (NET Zrt.) was tasked with providing assistance to families with high payments due to FX mortgage loans.Footnote 172 It was established by the Act CLXX of 2011,Footnote 173 for which HBA offered assistance throughout the legislative process.Footnote 174 According to their annual report, the legislation had been submitted with the prior consent of HBA, and they lauded its effects on the “expansion the circle of stakeholders”Footnote 175 in the relief of the FX loan crisis. OTP CEO Csányi deemed NET to be “a good solution”Footnote 176 although one his deputies was skeptical regarding the effectiveness and cost of the new agency.Footnote 177

Finally, the Central Credit Information System (KHR) was extended in the period between 2010 and 2014 (see also the above discussion of the topic). Prior to 2011, the ledger had only held information on individuals who had been late with debt repayment.Footnote 178 With the Act CXXII of 2011, the functions of KHR were extended with a positive debtor list.Footnote 179 The HBA provided assistance for the creation of KHR and suggested modifications for the bill in parliament.Footnote 180 They were supportive of the final version as well and praised the new regulation as a welcome addition to the informational system undergirding domestic finance.Footnote 181 It was a clear-cut success after the stalemate of the pre-2010 period although the initiative could also be seen as a way of compensation for all the losses that occurred due to the new bank taxes.Footnote 182 OTP took part in the information campaign surrounding the introduction of the new policy.Footnote 183

Discussion

In this section, we discuss our results from three perspectives. First, we consider potential explanations for the limited preference attainment of the banking lobby before 2010. Second, and on a related note, we return to the issues of correlation vs. causation in light of our data. Third, we consider some themes that are prevalent in the emerging political economy literature of the Orbán era.

As for the first topic, the comparison of ideal policy positions and actual policy outcomes regarding specific policy issues yielded promising results. The average PrefScore for the period 2010–14 based on press releases for the Top 10 issues was -0.3, while for the previous period of 2006–9 the average score was + 0.1. While the comparison of two different periods—along with the different set of major agenda items for the respective years—will always be reminiscent of comparing apples and oranges, our analysis does hold some lessons with regards to the dynamics of preference attainment of banking interests in Hungary.

It is clear from the case-by-case analysis of twenty major policy issues in banking and finance in the period between 2006 and 2014 that the bank lobby certainly did not succeed in “capturing” the state: their success in this department was mixed, at best, even before 2010. While the policy clout of HBA diminished somewhat from its value from the previous period, the average drop of 0.4 signals a half-turn rather than a revolution in the power balance between the government and banking interests under the second government of Viktor Orbán.

Two developments of the pre-2010 period may serve as explanations for more limited HBA preference attainment than what had been assumed in political debates. First, the global financial crisis spilled over into Hungary as an exogenous shock in October 2008, which resulted in inviting the IMF and the EU to provide financial support. This event, therefore, constitutes just as natural a cut-off point for periodization purposes as the 2010 election. In fact, the year and a half intermezzo before the second Orbán Administration took office should be considered a distinct period on its own right. This would also explain the smaller than expected gap between the pre- and post-2010 period.

On a related note, it is also notable that the socialist-liberal governments had already initiated a re-invention of state-business relations in the face of harsher budget realities by 2006–7. These years mark the end of the “golden age” for banking interests. While minor lobbying victories were still within reach—as manifested in the yearly reports—the creation of an Expert Committee on Retail Banking Services and other attempts at self-regulation signal a change of steps over previous lobbying approaches.

Secondly, our research design, as presented in the section on data and methods, does not in and of itself establish causation.Footnote 184 Policy outputs may be the product of factors unrelated to industry lobbying as was in the case of the positive debtor list (or positive credit registry). HBA had lobbied for the introduction of this regulatory institution for years before it became reality. However, many other actors, such as the central bank, were also in favor. It was the Hungarian Data Protection Supervisor that upheld the legislation on legal grounds. One could argue that the second Orbán government enacted the law creating the registry as compensation for new bank taxes (which would still make the case an instance of successful preference attainment). Furthermore, the positive debtor list was also featured in the agreement with the IMF, signed by the Hungarian government in 2008 as a condition for the IMF's loan. In sum, the registry became a law of the land for a number of reasons beyond HBA's lobbying support.

Cases such as these do not refute or discredit our analysis. Instead, they point toward the general limitation of the preference attainment framework. For this latter exercise, it only matters if a policy decision was in line with what the HBA was lobbying for. In this, preference attainment analysis does not substitute in-depth legislative or policy analysis focusing on causality in single cases. However, preference attainment has a competitive advantage over such process-tracing analyses in that it can provide an overview of policy impact in a complete policy subsystem over extended periods. And in the next step, preference attainment analysis can be enhanced with the inclusion of further institutional factors beyond interest group lobbying (such as the role of Data Protection Supervisor in the above example) and also external/exogenous effects (such as compliance with EU law or International Monetary Fund [IMF] recommendations or “softer” forms of coordination such as the Vienna Initiative).

Thirdly, above we noted that the preference attainment of the bank lobby certainly did not plunge during the second Orbán government (2010–14) vis-á-vis the previous legislative cycle. This finding, however, only applies to the period in question. The next two cycles of the third and fourth Orbán governments (from 2014 and 2018 on) ushered in a new era in which the government acquired direct state ownership or retained indirect control through the so-called “national capitalist” class in many financial institutions.

Orbán only formulated his policy to attain an over 50 percent share for “national” banking interests in the market in July 2012. And it took years for his government and the central bank to get this task done. Therefore, the actual timeline shows that this development falls mostly outside the scope of our study (which is 2006–14). Of the major deals, the Budapest Bank transaction was not sanctioned in our timeframe (it was decided on in December 2014 and came to effect even later).Footnote 185 A 15 percent stake in ERSTE was acquired in 2016.Footnote 186 Of these major investments only the MKB deal took place during the period in question, and even this would have a negligible effect on our actual analysis of preference attainment as it only was agreed on in the summer of 2014 and effectuated later on.Footnote 187

All these point toward the need for the reinterpretation of the narrative in international political economy, which singles out the 2010 election as a watershed in Hungarian financial policy. Contrary to the customary emphasis on electoral change, at least in the case of Hungary, the origins of financial nationalism (as manifested in more heavy-handed regulation and a loss of policy clout on behalf of banking interests) go back years before Orbán's 2010 electoral victory. The 2006 budget cutbacks and the financial crisis of 2008 ushered in a new era in business/government relations in the financial sector, which paved the way for the even more pronounced policy switch after 2010. In the not so parallel universe of political communication, this process was accompanied by a gradual collapse of the policy regime preceding financial nationalism: modernization consensus.Footnote 188

And this gradualism also hallmarked the periods of consecutive post-2010 Orbán governments. Populist rhetoric was put into practice in earnest after a series of setbacks in the negotiations with the international financial elite. The paradigmatic case in point is related to the de facto nationalization of the private (second) pillar of the pension system.Footnote 189 In talks with the EU, starting from 2010, the Hungarian government asked, along with eight other EU countries, the Commission “to modify its earlier decisions of 2005 and take into full account the transition costs of pension privatization in the budget deficit and the government debt.”Footnote 190 The Commission declined and the rest is history: Contributions due to the private pension funds were redirected to the treasury and private pension fund members were, for the most part, reintegrated in the public pillar.Footnote 191

Finally, the dynamics of “domestic” vs. international banks on the Hungarian market is more complex than one would assume. The position of OTP, the biggest bank and the most important one, which did not form part of an international financial conglomerate, was overwhelmingly in line with that of the HBA in the eight years in question. For the two issues for which we registered some minor deviation from the HBA line—the positive debtor list and the National Asset Management Agency—we could not speak of any major disagreement only different emphases.

Similar deviations for other members would be equally acceptable as no two major banks are in a perfectly similar business position in the Hungarian financial markets. In the period between 2006 and 2014 unity among banking factions was mostly forged by facing the same adversaries (governments stepping up their regulatory efforts and increasing tax levels, unregulated brokerages, the Data Protection Supervisor, etc.). Even in the few cases where discord set in the fault lines were not between major “foreign” and major domestic banks but the significant players and smaller ones.

This is not to say that these findings can be extrapolated beyond these two government cycles. OTP did pursue an alternative strategy with regards to FX loans back in the early 2000s. And the banking conglomerates, which directly or indirectly came under the control of the government from 2014 on, certainly enjoyed some privileges. But these were “domestic banks” in a thoroughly different manner: the goal was not to nationalize a greater portion of the Hungarian banking system so much as to make sure that they are under “Hungarian control.” As Viktor Orbán put it in 2014:

“(With the Budapest Bank transaction) Hungarian ownership in the banking system has surged to well above 50 percent. We can feel more or less secure now. The point is not that a bank should be state-owned—I'd be cautious in this respect—but the point is that they are under Hungarian control.”Footnote 192

In this sense, OTP was never a truly “domestic” bank, neither in terms of ownership nor in terms of its role in the “system of national cooperation” installed by Orbán. Having said that, these issues came to the forefront after the timeframe (2006–14) of the present article.

Conclusion

In this article, we addressed a puzzle in the politics of Hungarian banking. By 2010, from the alleged position of state capture, banks slid into a “pariah” status in domestic political discourse in a matter of just a few years. This was rooted in the financial and social crises of the period before the 2010 parliamentary elections. Critics from both the Left and Right denounced the coziness of MSZP-SZDSZ coalition governments with banking interests. The image of a “government of bankers” has taken hold in the public imagination, which played a key role in the constitutional majority of the Fidesz after the elections. The victory of Prime Minister Viktor Orbán led to a sea-change in financial policy that explicitly targeted financial interests both in terms of regulation and taxation. Nevertheless, by 2013, the banking sector as a whole returned to positive earnings,Footnote 193 and by 2017 banks broke historic records of profitability.

We set out to investigate this puzzle by an analysis of the preference attainment of the banking lobby both before and after 2010. We adopted a computer-assisted qualitative content analysis to match the HBA and OTP policy positions with legislative outcomes. Our results showed that the banking lobby did, in fact, lose its edge in preference attainment on major policy issues after 2010. The same applied to OTP, the biggest bank on the Hungarian market. Nevertheless, this shift was less marked then what one would believe based on the vehemence of political debates and antibanking rhetoric. Indeed, seismic activity was already under way after 2006 in terms of the HBA's policy clout.

Our research contributes to the literature with the first systematic analysis of the preference attainment of the banking lobby in a Central Eastern European context. In this, it deepens our understanding of the influence of banking associations on government policy, with a relatively under-researched case of a new EU member state.Footnote 194 These findings also offer a more nuanced view of bank power over policymaking in post-communist Hungary than what is available in most popular treatments, including official government communication in the post-2010 period. In this our research fills a gap in the literature when it comes to the role of a key interest group in shaping legislation for a region for which such studies are scarce.

The article also shed light on the programmatic positions of right-wing populist governments while in power. Its focus on economic policies provides a contribution to the literature on populism, which has largely focused on government policies related to democracy, the rule of law, or immigration.

Given the transparent methodology of the project, generalizability may be less of an issue of replicability than of research capacity. In terms of methods, PrefScore may be used in studies of preference attainment, which are unrelated to either Hungary or banking. As for substance, the spread of illiberalism and antifinance rhetoric across Europe, notably in Poland, provides fertile ground for similar studies. These could unearth the policy compromises that are prevalent in financial regulation notwithstanding the hardline political messaging of illiberal governments.

Future research may both focus on the refinement of the underlying methodology and connecting these results—limited to the politics of interest groups—to the wider literature (we addressed this latter topic in the Discussion). As for methods, despite its inherent methodological limitations, the general PrefScore-based approach holds some advantages over other measurements of policy influence. First, it offers a transparent system of coding and analysis that travels beyond banking and finance and the geographical context of Hungary. Second, it is also suitable for more in-depth analysis of issue-specific (as opposed to organization-specific) lobbying success. What requires more methodological work is the reproducible selection of issues, which poses a problem mainly because of the dynamic nature of policy issues. Here, future research may consider a year-by-year analysis of topics, such as bank taxation, as the level of preference attainment may change with every fiscal year.

Issues may also be varied in the intensity of lobbying that they engender. Nevertheless, it would require an entirely different research design—one that is based on interviews with individual banking leaders and could only focus on a handful of key cases. Still, the case selection of such studies could certainly benefit from the computer-assisted content analysis of relevant documents, which provides a systematic way for the compilation of the list of potential topic candidates important for banking interests.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the support the Hungarian Foundation for the History of Politics (Politikatörténeti Intézet). We thank the three anonymous reviewers and the participants of the workshop “The Politics and Political Economy of Bank Reform” (conveners: Huw Macartney and David Howarth) at the ECPR Joint Sessions in 2018 for their thoughtful comments.