No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

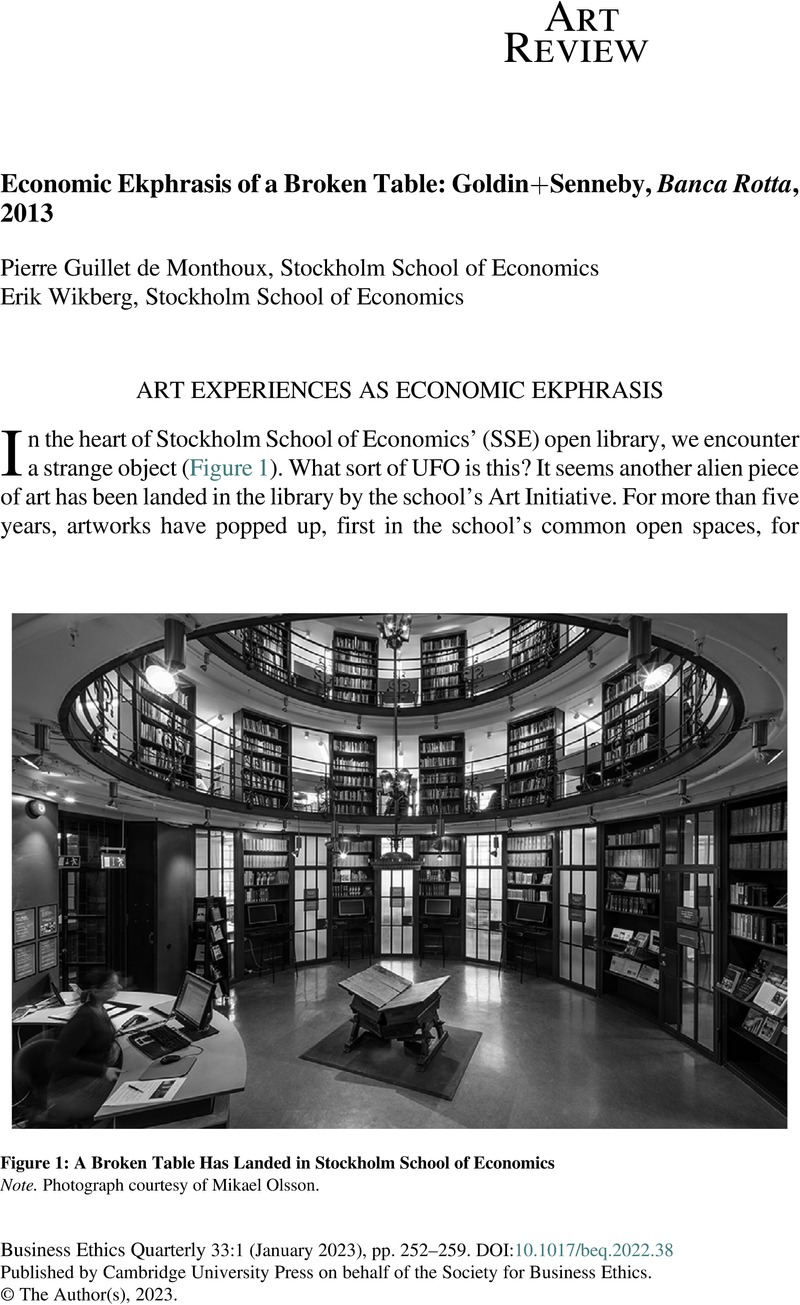

Economic Ekphrasis of a Broken Table: Goldin+Senneby, Banca Rotta, 2013

Review products

Economic Ekphrasis of a Broken Table: Goldin+Senneby, Banca Rotta, 2013

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 01 February 2023

Abstract

An abstract is not available for this content so a preview has been provided. Please use the Get access link above for information on how to access this content.

- Type

- Art Review

- Information

- Copyright

- © The Author(s), 2023. Published by Cambridge University Press on behalf of the Society for Business Ethics

References

REFERENCES

Birchall, Clare. 2021. “The Economy of Secrets and the Secrets of the Economy.” In Economic Ekphrasis: Goldin+Senneby and Art for Business Education, edited by Guillet de Monthoux, Pierre and Wikberg, Erik, 205–13. Berlin: Sternberg Press.Google Scholar

Fraiberger, Samuel P., Sinatra, Roberta, Resch, Magnus, Riedl, Christoph, and Barabási, Albert-Lázló. 2018. “Quantifying Reputation and Success in Art.” Science 362 (6416): 825–29.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Goldin+Senneby. n.d.-a. “Banca Rotta.” https://goldinsenneby.com/practice/banca-rotta.Google Scholar

Guillet de Monthoux, Pierre, and Wikberg, Erik. 2021. Economic Ekphrasis: Goldin Senneby and Art for Business Education. Berlin: Sternberg Press.Google Scholar

LinkedIn. n.d. “Goldin+Senneby.” https://www.linkedin.com/company/goldin-senneby/about/.Google Scholar

Nilson, Isak, and Wikberg, Erik. 2021. Artful Objects—Graham Harman and the Business of Speculative Realism. Berlin: Sternberg Press.Google Scholar

Rorty, Richard. 1994. “Do We Need Ethical Principles?” Talk at the Vancuver Insitute. YouTube video, 1:24:13. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SDAdveMYHFs.Google Scholar

Selander, Lina. 2022. “Soli Deo Gloria.” https://www.linaselander.com/public-commissions/soli-deo-gloria-handelshogskolan.Google Scholar

Sjöberg, Örjan. 2021. “Banca Rotta as Memento Mori—or Is There Simply No Need to Bother?” In Economic Ekphrasis: Goldin+Senneby and Art for Business Education, edited by Guillet de Monthoux, Pierre and Wikberg, Erik, 79–87. Berlin: Sternberg Press.Google Scholar

Stockholm School of Economics. n.d. “Mission and Vision.” https://www.hhs.se/en/about-us/organization/mission-and-vision/.Google Scholar