The governance of business activities along global production networks (Levy, Reference Levy2008) is crucial to dealing with the negative social and environmental side effects these activities create or reinforce (Djelic & Quack, Reference Djelic and Quack2018; Djelic & Sahlin-Andersson, Reference Djelic and Sahlin-Andersson2006). One such governance mechanism is multi-stakeholder initiatives (MSIs) (Mena & Palazzo, Reference Mena and Palazzo2012; Rasche, Reference Rasche2012). MSIs are private regulatory instruments that govern global business activities to reduce their negative societal impacts through voluntary compliance by firms to social and/or environmental standards or codes of conduct throughout their supply chains (Bartley, Reference Bartley2007; Scherer & Palazzo, Reference Scherer and Palazzo2007; Vogel, Reference Vogel2010). For example, the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) is an MSI that governs the sustainable management of forests worldwide.Footnote 1 In contrast with industry self-regulation (King & Lenox, Reference King and Lenox2000) or business-driven programs (Fransen, Reference Fransen2012), which the corporate sector sets up mostly for public relations and managing the image of their industries (Marques, Reference Marques2017), MSIs involve stakeholders from two or more sectors (for-profit, public, and nonprofit) in their formal decision-making processes.

Yet, even MSIs that involve a variety of stakeholders and try to balance different interests in their procedures have been criticized when it comes to governing global business activities (e.g., Banerjee, Reference Banerjee2018). Concerns have been raised about the excessive role MSIs give to corporate actors (Hussain & Moriarty, Reference Hussain and Moriarty2018) and their lack of impact for disadvantaged actors across global production networks, such as workers in garment factories or Indigenous communities (de Bakker, Rasche, & Ponte, Reference de Bakker, Rasche and Ponte2019; MSI Integrity, 2020). MSIs’ governance role is contested in part because deliberations between stakeholders on rule setting often do not meet standards expected of regulatory actors. Yet, many political theorists view the quality of deliberations as essential for legitimate, just, and equitable governance (Habermas, Reference Habermas1996).

According to deliberative democratic theory, the quality of deliberations can be assessed in terms of their deliberative capacity (Dryzek, Reference Dryzek2009). In MSIs, enhancing deliberative capacity means, for instance, the broad inclusion of different types of stakeholders affected by the regulated business activities, the structuring of fair and reciprocal deliberations, and making sure these deliberations are consequential in terms of effectively curtailing the problems created by the business activities (e.g., Arenas, Albareda, & Goodman, Reference Arenas, Albareda and Goodman2020; Mena & Palazzo, Reference Mena and Palazzo2012; Scherer & Palazzo, Reference Scherer and Palazzo2011). The greater the deliberative capacity of MSIs is, the better they are at governing global business activities that no nation-state or company can solve alone. Yet, the deliberative capacity of MSIs has been questioned, as they only include marginalized actors in a limited fashion (Banerjee, Reference Banerjee2018), tend to favor corporate interests (Hussain & Moriarty, Reference Hussain and Moriarty2018), and have limited regulatory impact (de Bakker et al., Reference de Bakker, Rasche and Ponte2019; LeBaron & Lister, Reference LeBaron and Lister2022).

Given these concerns, enhancing the deliberative capacity of MSIs is crucial if they are to effectively curtail the social and environmental problems created by global business activities. Prior research has already begun addressing this problem (Schormair & Gilbert, Reference Schormair and Gilbert2021). For instance, Arenas and colleagues (Reference Arenas, Albareda and Goodman2020) discuss the need for some degree of dissensus in deliberations between stakeholders and explore how such fruitful contestation can be introduced in MSIs. Others have examined how the initial lack of mutual understanding between for-profits and nonprofits in MSIs can be overcome by fostering mind-sets and values geared toward finding common ground (Soundararajan, Brown, & Wicks, Reference Soundararajan, Brown and Wicks2019).

In this article, we advance this research by asking the question, How can deliberative mini-publics (DMPs) improve the deliberative capacity of MSIs? To answer this question, we first adopt a deliberative systems perspective. This perspective takes a fine-grained view of polities, viewing them as systems made of different elements (such as public space or accountability) and emphasizing the division of deliberative labor across these elements (Elstub, Ercan, & Mendonça, Reference Elstub, Ercan and Mendonça2019; Mansbridge et al., Reference Mansbridge, Bohman, Chambers, Christiano, Fung, Parkinson, Thompson, Warren, Parkinson and Mansbridge2012). Deliberative capacity can thus be assessed in a more fine-grained way at the levels of the system and its elements (Curato, Reference Curato2015; Dryzek & Stevenson, Reference Dryzek and Stevenson2011; O’Flynn & Curato, Reference O’Flynn and Curato2015). The deliberative systems perspective is applicable to a wide range of polities, including global climate governance, transnational governance networks, and liberal democratic nation-states (Dryzek, Reference Dryzek2016; Dryzek & Stevenson, Reference Dryzek and Stevenson2011; Mansbridge et al., Reference Mansbridge, Bohman, Chambers, Christiano, Fung, Parkinson, Thompson, Warren, Parkinson and Mansbridge2012). Because MSIs formally include different stakeholders in their governance structures, they meet the threshold of being “loosely democratic” and are thus suitable for analysis as deliberative systems (Mansbridge et al., Reference Mansbridge, Bohman, Chambers, Christiano, Fung, Parkinson, Thompson, Warren, Parkinson and Mansbridge2012: 7–8).

DMPs are a prominent and influential democratic innovation (Elstub, Reference Elstub, Elstub and McLaverty2014) that have received significant attention in research on deliberative systems given their potential to improve deliberative capacity (Curato & Böker, Reference Curato and Böker2016; Felicetti, Niemeyer, & Curato, Reference Felicetti, Niemeyer and Curato2016). DMPs are “bodies comprised of ordinary citizens chosen through near random or stratified selection from a relevant constituency, and tasked with learning, deliberating, and issuing a judgement about a specific topic, issue, or proposal” (Warren & Gastil, Reference Warren and Gastil2015: 562). They advance a novel form of nonelectoral representation, “citizen representatives,” whereby participants are authorized to undertake a representative function but are not beholden to electoral accountability (Urbinati & Warren, Reference Urbinati and Warren2008; Warren, Reference Warren, Warren and Pearse2008). “Standing for” (Pitkin, Reference Pitkin1967: 60) the broader population, these representatives create presence through their descriptive representativeness (James, Reference James, Warren and Pearse2008; Zakaras, Reference Zakaras2010), whereby they “are in their own persons and lives in some sense typical of the larger class of persons whom they represent” (Mansbridge, Reference Mansbridge1999: 629).

To build a case for how DMPs can enhance the deliberative capacity of MSIs, we first conceptualize MSIs as deliberative systems and discuss challenges MSIs often face in terms of meeting criteria of deliberative capacity. We then theorize how DMPs, when carefully translated to the context of MSIs through specific design parameters, can address deficiencies in MSIs’ deliberative capacity. In doing so, we make two major contributions to the literature on MSIs. First, we advance a new way of seeing and improving the deliberative capacity of MSIs. Indeed, by explicitly adopting a systems perspective on MSIs (which, to date, has only been alluded to in the literature, e.g., Arenas et al., Reference Arenas, Albareda and Goodman2020; Soundararajan et al., Reference Soundararajan, Brown and Wicks2019), we open the “black box” of MSIs and show the variegated forms of and settings in which deliberations take place not only within MSIs, among their formal members, but also beyond, with other external actors (Fougère & Solitander, Reference Fougère and Solitander2020). This allows for a more fine-grained analysis of deficits in deliberative capacity at different levels of the system. On the basis of this analysis, MSIs can adopt one or more of the five uses of DMPs we developed, each of which can improve the deliberative capacity of a focal element of the system and that of the system as a whole.

Second, we contribute to our understanding of democratic representation in MSIs, a topic which to date has received minimal explicit attention (for an important exception, see Reinecke & Donaghey, Reference Reinecke and Donaghey2021). MSIs tend to represent the many different stakeholders affected by their operations by following a form of structural representation in their governance structures (Reinecke & Donaghey, Reference Reinecke and Donaghey2021), bundling similar interests (e.g., corporate, environmental, Global South) together in constituencies and authorizing representatives (i.e., through election or appointment) to represent these constituencies. Yet, some stakeholders cannot be represented structurally and, rather, rely on representation through self-appointed representatives who make representative claims, such as when nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) represent the natural environment (Baur & Palazzo, Reference Baur and Palazzo2011; Reinecke & Donaghey, Reference Reinecke and Donaghey2021). These methods of representation have been criticized for leading to deep-seated inequalities in terms of how different actors and interests are represented in MSIs (Banerjee, Reference Banerjee2018; Schouten, Leroy, & Glasbergen, Reference Schouten, Leroy and Glasbergen2012). Through our elaboration on the use of DMPs in MSIs, we advance a complementary form of nonelectoral representation that can alleviate some of these concerns and provide additional benefits to MSIs.

Our article proceeds as follows. We begin by briefly overviewing MSIs, to then conceptualize them as deliberative systems and analyze their deliberative capacity. We then introduce DMPs and their key features, which sets us up for our translation of DMPs to the context of MSIs and our theory development about five uses through which they can improve MSIs’ deliberative capacity. We conclude with a discussion of our contributions to research and directions for future research.

THE DELIBERATIVE CAPACITY OF MULTI-STAKEHOLDER INITIATIVES

Multi-Stakeholder Initiatives

MSIs are typically defined as formal “coalitions of nonstate actors [that] codify, monitor, and in some cases certify firms’ compliance with labor, environmental, human rights, or other standards of accountability” (Bartley, Reference Bartley2007: 298). Core aspects of MSIs thus include rule making, the monitoring of rule taking and potential sanctioning of noncompliance, and the participation of actors in a deliberative platform aimed at exchange and learning between diverse members (Palazzo & Scherer, Reference Palazzo, Scherer, Rasche and Kell2010). Compliance by firms is voluntary, and MSIs thus rely on market mechanisms to ensure compliance, such as certification, product labeling, or reputational threat of activism (Vogel, Reference Vogel2010). A key distinctive feature of MSIs is a degree of inclusiveness of a variety of actors, including actors from two or more sectors (corporate, public, and civil society), in their decision-making and governance processes (Mena & Palazzo, Reference Mena and Palazzo2012). This means that corporations share decision-making power, to various extents, with noncorporate stakeholders, such as governments, unions, NGOs, scientific organizations, and Indigenous communities.

The FSC provides a good example. It elaborates principles for sustainable forest management that inform standards with which member firms from various industries (from logging to pulp and paper to home improvement) decide to voluntarily comply and with which to get certified through an independent verification process by accredited third parties. The principles, standards, and verification procedures, along with other rules and processes, are elaborated and decided upon by various actors that are members of the FSC, including firms, social and environmental NGOs, governmental agencies, representatives of Indigenous communities, academics, and union representatives. These members are part of the General Assembly, representing equally industry, social, and environmental actors, which elects the Board of Directors that leads the initiative. The FSC’s operations are run by an Executive Team and a Secretariat, along with many country chapters.

MSIs are varied, but as the FSC illustrates, their structure typically includes 1) an assembly of members (or their delegates) who, as the highest decision-making body of the initiative, make rules for corporate conduct; 2) a board, usually made of representatives of these members and often elected by the assembly; 3) a secretariat or executive team that deals with the implementation of the rules and day-to-day operations; 4) several different working groups or committees pertaining to different aspects of the MSI (such as rule-making processes and monitoring mechanisms); and, finally, 5) some sort of oversight mechanisms regarding the implementation of the rules by firms (including monitoring, complaints, and sanction procedures).

It is important to distinguish different types of actors related to MSIs. First are members: the stakeholders that are involved in its governance and participate in the rule- and decision-making processes (point 1); they usually are the ones that are directly affected by or affect the issues governed by the MSI. Second are rule takers: the corporations that voluntarily comply with the MSI rules. Rule takers (or some of them) are often MSI members, too, involved in MSI governance, and are thus rule makers as well. Third are monitors: the actors tasked with auditing rule takers’ adoption of rules, oftentimes NGOs or consulting firms (Gereffi, Garcia-Johnson, & Sasser, Reference Gereffi, Garcia-Johnson and Sasser2001). They can also sometimes be members. Finally are otherwise affected stakeholders: those that are not rule takers or rule makers but are nevertheless affected by the issues addressed by the MSI (Brès, Mena, & Djelic-Salles, Reference Brès, Mena and Djelic-Salles2019; Martens, van der Linden, & Wörsdörfer, Reference Martens, van der Linden and Wörsdörfer2019). In the case of the FSC, these could be some consumers, Indigenous groups, features of the natural environment, or governments that are not members of the FSC.

This connects to the issue of representation of different stakeholders in MSIs, which generally takes the form of structural representation (Reinecke & Donaghey, Reference Reinecke and Donaghey2021). This conception emphasizes the formal relationship between the represented and their representatives, focusing on how representatives are authorized and held accountable (Pitkin, Reference Pitkin1967). MSIs’ member organizations usually appoint a delegate to act on their behalf at meetings like those of the general assembly, enacting the organization’s instructions and mandates (Pitkin, Reference Pitkin1967). MSIs can have different chambers in their assembly representing particular constituencies, such as sectors, stakeholder groups, or interests (e.g., environmental stakeholders, workers’ stakeholders). This means that, indirectly, interests are bundled or aggregated by predetermined and similar interests among stakeholders. For instance, the FSC divides its assembly into equal parts between social, environmental, and economic actors. The respective members of each chamber then elect four representatives on the board for a total of twelve directors. As this example illustrates, beyond the assembly, MSIs also have a board of representatives, who serve as “trustees” (Pitkin, Reference Pitkin1967) of a broad constituency—in this case, these “bundled” stakeholders that elect one or more representatives on the board. These representative structures mimic the “standard account” that sees representation as a principal–agent relationship whereby representatives are expected to—and, through elections, often incentivized to—advance the interests of citizens in specific constituencies (Montanaro, Reference Montanaro2012; Urbinati & Warren, Reference Urbinati and Warren2008). MSIs, though, differ from this standard account in important ways, including the fact that they do not govern over a clearly defined territory with citizens/residents (Bäckstrand, Reference Bäckstrand2006), their population is less clearly defined and more homogeneous (Reinecke & Donaghey, Reference Reinecke and Donaghey2021), and they rely on market mechanisms and potential sanctions to foster compliance (Mena & Palazzo, Reference Mena and Palazzo2012). These peculiarities also mean that, in addition to structural representation, MSIs involve self-appointed representatives like NGOs and activists that make representative claims on behalf of some stakeholders (e.g., the natural environment, workers) but are not formally authorized to act in a representative capacity (Baur & Palazzo, Reference Baur and Palazzo2011; Reinecke & Donaghey, Reference Reinecke and Donaghey2021).

The Elements of Deliberative Systems

A major advancement offered by the deliberative systems perspective is that it focuses on how deliberation takes place across different elements of a system. As Elstub and colleagues (Reference Elstub, Ercan and Mendonça2019: 139) put it, this entails “an understanding of deliberation as a communicative activity that occurs in multiple, diverse yet partly overlapping spaces, and emphasizes the need for interconnection between these spaces.” Dryzek and collaborators have been particularly influential in terms of developing a more general model of a deliberative system (Dryzek, Reference Dryzek2009, Reference Dryzek2010; Dryzek et al., Reference Dryzek, Bowman, Kuyper, Pickering, Sass and Stevenson2019; Dryzek & Stevenson, Reference Dryzek and Stevenson2011; Stevenson & Dryzek, Reference Stevenson and Dryzek2014). This is highly adaptable, as scholars can focus on the elements deemed most relevant to particular contexts being studied (e.g., Curato, Reference Curato2015; Stevenson & Dryzek, Reference Stevenson and Dryzek2014). In conceptualizing MSIs as deliberative systems, we focus on what we see as the five most relevant elements of the system: public space, empowered space, transmission mechanisms, accountability mechanisms, and meta-deliberation. In the context of the liberal democratic nation-state, the public space involves spaces like cafés, internet forums, and public hearings with few or no constraints on who can participate or what they can say. The empowered space entails spaces, such as cabinets, legislatures, and courts, that are empowered to make collective decisions. Transmission mechanisms are the means through which the public space can influence decision-making in the empowered space, including political campaigns, personal connections, and broader cultural changes. Accountability mechanisms are the means through which the empowered space provides an account to and can be held accountable by the public space. These can include public forums and the threat of electoral defeat. Finally, meta-deliberation entails the capacity of a system to self-examine (e.g., constitutional reform) and adapt. Figure 1 provides a schema of the connections among these various elements in the case of the FSC.

Figure 1: The FSC as a Deliberative System

Note. Adapted from O’Flynn and Curato (Reference O’Flynn and Curato2015) and Dryzek and colleagues (Reference Dryzek, Bowman, Kuyper, Pickering, Sass and Stevenson2019).

We now turn to our conceptualization of MSIs as deliberative systems. Table 1 summarizes this content, with the letters in the left-hand column corresponding to Figure 1 and providing examples from the FSC. The public space of MSIs is broad and encompasses deliberations in many sites that can be open to participation to different extents. For instance, corporations—whether or not MSI members—often exchange in the context of chambers of commerce, industry associations, or think tanks, whereas NGOs concerned with the environment or trade unions often discuss in conferences or workshops. The public space includes sites that are open to more diverse participation, such as online open spaces; media of various sorts; business or economic conferences; and various types of academic, trade union, and nonprofit conferences and seminars.

Table 1: MSIs as Deliberative Systems and Common Pitfalls in Their Elements’ Deliberative Capacity

c See https://fsc.org/en/about-us.

The empowered space of an MSI corresponds to the formal structural bodies described earlier (assembly, board, secretariat, and working groups) and is similar to the legislative, executive, and judicial organs that are involved in the collective decisions of liberal democratic nation-states.

Transmission mechanisms in MSIs typically consist of pressure from various groups from the public space targeted at actors in the empowered space, most often the board and secretariat. MSIs are usually under a lot of direct pressure from various groups, in particular, economic ones (e.g., business associations; see Fransen, Reference Fransen2012) or civil society representatives of various social and environmental interests (e.g., Mena & Waeger, Reference Mena and Waeger2014). Indeed, as mentioned previously, MSIs rely on market mechanisms, such as reputational threat, to increase compliance (Vogel, Reference Vogel2010). For instance, the FSC is regularly criticized by various civil society actors, and some of these critiques can be found on the FSC-Watch website.Footnote 2 Pressure can be indirect, too, for instance, the result of broader societal movements (e.g., Extinction Rebellion). In addition, formal representative processes, such as elections to the board, provide another transmission mechanism for stakeholders to push their agenda on the empowered space of the MSI.

In terms of accountability, MSIs have a number of mechanisms to make the empowered space accountable to MSI members and the public more generally. Usually, MSIs and their secretariats publicly report on their activities, performance (understood as adequate compliance by participating firms), and progress. Transparency and access to information are, therefore, key to these indirect accountability mechanisms (Auld & Renckens, Reference Auld and Renckens2017; Bäckstrand, Reference Bäckstrand2006; Hale, Reference Hale2008). For instance, the FSC publishes an annual report, but also position papers, reports by certification bodies on corrective action requests, and overviews of scientific studies on the FSC’s impact.Footnote 3 To verify compliance, as described earlier, there are usually a number of monitoring procedures in MSIs to verify and ensure compliance, as well as remedies for noncompliance when found. Sanctions are also sometimes in place, such as decertification.

Finally, meta-deliberation refers to the ability of a polity to self-reflect and change itself. MSIs vary in the extent to which they self-reflect, although this element is not prominent in MSIs. Usually, mechanisms of meta-deliberation involve the ability of the assembly to change some processes and rules. For instance, the participants in the FSC Assembly can propose motions to change FSC rules before the assembly every three years.

The Deliberative Capacity of Multi-Stakeholder Initiatives

A parallel area of inquiry on deliberative systems has focused on how to evaluate them and their various elements. In this article, we rely on the notion of deliberative capacity, defined as “the extent to which a political system possesses structures to host deliberation that is authentic, inclusive, and consequential” (Dryzek, Reference Dryzek2009: 1382). Inclusiveness captures the breadth of discourses and interests circulating in a setting; authenticity captures the extent to which the deliberation “induce[s] reflection noncoercively, connect[s] claims to more general principles, and exhibit[s] reciprocity” (Dryzek, Reference Dryzek2009: 1382); and consequentiality (sometimes equated with the notion of decisiveness, e.g., Curato, Reference Curato2015) captures the direct and indirect ways in which these authentic and inclusive deliberations can impact collective decision-making and outcomes. Schouten and colleagues (Reference Schouten, Leroy and Glasbergen2012) further usefully distinguish between output and outcome consequentiality in MSIs: output consequentiality refers to whether deliberations meaningfully affect MSIs’ decisions, whereas outcome consequentiality refers to the actual impact MSIs have on the industries they attempt to regulate.

The criteria of deliberative capacity can be used to make assessments of the system as a whole or to make a more fine-grained assessment of its elements. The former approach has been undertaken in some limited research on MSIs to date (Schouten et al., Reference Schouten, Leroy and Glasbergen2012; Soundararajan et al., Reference Soundararajan, Brown and Wicks2019). While the deliberative capacity of different MSIs varies widely, general criticisms have been leveraged against them. In terms of their inclusiveness, MSIs are said to exclude or not include meaningfully marginalized stakeholders, such as Indigenous people or local communities (Banerjee, Reference Banerjee2018). In terms of their authenticity, while, in general, MSIs fare fairly well in terms of reflection on preferences and reciprocity between actors (see, e.g., Moog, Spicer, & Böhm, Reference Moog, Spicer and Böhm2015; Schouten et al., Reference Schouten, Leroy and Glasbergen2012), they have been criticized for lack of fairness in deliberations, mostly because of overrepresentation of corporate interests and excessive corporate power (Banerjee, Reference Banerjee2021; Hussain & Moriarty, Reference Hussain and Moriarty2018). MSIs have also been criticized for low consequentiality (for an overview, see de Bakker et al., Reference de Bakker, Rasche and Ponte2019; LeBaron & Lister, Reference LeBaron and Lister2022). Indeed, some MSIs tend to exclude marginalized discourses—especially more radical views of sustainability—and thus have been criticized for their lack of output consequentiality, as these discourses do not meaningfully affect MSI decisions (Schouten et al., Reference Schouten, Leroy and Glasbergen2012). In terms of outcome consequentiality, one prominent critique is the low number of firms from a given industry that actually comply with MSI rules (e.g., Moog et al., Reference Moog, Spicer and Böhm2015; Schouten et al., Reference Schouten, Leroy and Glasbergen2012). Furthermore, the lack of substantial changes in areas that MSIs regulate has also been pointed out. For instance, the FSC has been criticized for allowing human rights violations, such as the rape of women and girls in the forest industry, because of the lack of clearly assigned responsibility for this issue in the FSC’s processes (Whiteman & Cooper, Reference Whiteman and Cooper2016; see also Bartley, Reference Bartley2018).

Yet, there is value in a more fine-grained assessment of the deliberative capacity of the system’s distinct elements. Premised on the idea that “the deliberative system as a whole is diminished by any nondeliberative substitute for any element” (Dryzek, Reference Dryzek2009: 1386), an analysis of a system’s elements avoids the potential pitfall of purely system-level evaluations. Indeed, there is a risk that a deliberative system could be assessed as having a high level of deliberative capacity without any meaningful deliberations occurring within it (Owen & Smith, Reference Owen and Smith2015). Per Dryzek (Reference Dryzek2009; see also Curato, Reference Curato2015), consequentiality is usually only examined in terms of the system as a whole, because it assesses the link between deliberations throughout the system to its decisions and outcomes. The empowered space, the public space, transmission, and accountability should be assessed in terms of their authenticity, and the public space and the empowered space should be assessed in terms of their inclusiveness and authenticity. Meta-deliberation can be assessed at the level of the system based on its authenticity and inclusiveness (Holdo, Reference Holdo2020; Thompson, Reference Thompson2008). We now examine common pitfalls in MSIs to demonstrate how this more fine-grained analysis could be undertaken. This is summarized in the right-hand columns of Table 1. These complement the system-wide pitfalls in consequentiality discussed earlier.

The empowered space of MSIs is the element that has attracted the most criticism. In terms of inclusiveness, the formal bodies of MSIs usually present high barriers to entry for marginalized stakeholders (Miller & Bush, Reference Miller and Bush2015), which is linked to inadequate representation of interests (Baur & Palazzo, Reference Baur and Palazzo2011; Reinecke & Donaghey, Reference Reinecke and Donaghey2021). For instance, it is often taken for granted that environmental NGOs (such as Greenpeace or the WWF) will represent the interests of Earth and its ecosystems, yet these organizations necessarily prioritize some environmental issues and interests over others (e.g., Bendell, Reference Bendell2005). With regard to authenticity, the empowered spaces of MSIs are often structured in an egalitarian manner; yet, this structure has been criticized for being biased toward economic interests in practice. For example, even though the FSC structurally balances interests, it has been critiqued for favoring Northern, economic, and corporate interests (Dingwerth, Reference Dingwerth2008; Moog et al., Reference Moog, Spicer and Böhm2015). This bias translates into a lack of fairness, as MSIs do not tend to make participation in deliberations easier for noncorporate actors, for example, in terms of language (Roussey, Balas, & Palpacuer, Reference Roussey, Balas and Palpacuer2022). Beyond structural issues, the authenticity of deliberations in the empowered space is critiqued for being prone to coercion, in particular, excessive corporate power over noncorporate stakeholders (Taylor, Reference Taylor2005), the co-optation of minority interests (Dawkins, Reference Dawkins2021; Maher, Reference Maher2019), and the silencing of dissenting opinions (Brown & Dillard, Reference Brown and Dillard2013).

The public space of MSIs is also sometimes pointed out as lacking inclusiveness and authenticity. In terms of inclusiveness, the public space of MSIs is usually quite global and encompasses various sites. Yet, some actors are excluded from deliberating in those sites, such as disenfranchised groups like Indigenous communities in remote areas or workers at the bottom of supply chains (Banerjee, Reference Banerjee2021). In terms of authenticity, these sites have been shown to be dominated by a neoliberal view that favors corporate interests over those of other stakeholders (Fougère & Solitander, Reference Fougère and Solitander2020). Even if divergent views exist, deliberations tend to be located in particular sites and not shared more broadly to challenge mainstream views (Schouten et al., Reference Schouten, Leroy and Glasbergen2012; Soundararajan et al., Reference Soundararajan, Brown and Wicks2019).

Prior work suggests that the authenticity of transmission mechanisms in MSIs is limited. Deliberations in the public space tend to be dominated by corporate and economic interests over those of other stakeholders, and therefore views that diverge from these interests tend not to be shared more widely in the public space. This means that when the outcomes of public space deliberations are transmitted to the empowered space of MSIs, they tend to be low in authenticity, because deliberations about what needs to be transmitted are co-opted by corporate actors and divergent views are silenced. This is reinforced by the power of industry associations and other corporate groups that pressure the empowered space through lobbying—a key transmission mechanism—more so than other actors (e.g., Marques, Reference Marques2017). Although noncorporate stakeholders are able to exert some pressure on the empowered space, mostly through activism—which can be directed at the MSI or at participating firms (Mena & Waeger, Reference Mena and Waeger2014)—corporate lobbying usually dominates (Hussain & Moriarty, Reference Hussain and Moriarty2018).

Accountability is also criticized in MSIs in terms of its authenticity. Reporting by the secretariat (e.g., annual reporting) tends to be dictated by the dominant coalition in an MSI, which is often the corporate sector. Similarly, reports on audits by certification bodies are often one-sided and relatively superficial, as the monitoring system on which MSIs usually rely has shown its limits in terms of audit fatigue and lack of resources to investigate noncompliance in depth (Marshall, McCarthy, McGrath, & Harrigan, Reference Marshall, McCarthy, McGrath and Harrigan2016). As mentioned earlier, symbolic adoption and mostly surface-level compliance are problematic too (Behnam & MacLean, Reference Behnam and MacLean2011). Concerns about the lack of adequate grievance mechanisms, effective means of sanctioning, and the lack of independent sanctioning bodies have also been raised (MSI Integrity, 2020).

Finally, meta-deliberation is not usually prominent in MSIs, as they do not necessarily have the capacity to fundamentally change their structures or practices. As Barlow (Reference Barlow2021: 16) argues, “dramatic design improvements are necessary before MSIs will fully achieve their potential.” Yet, such structural change is often brought about by the secretariat, which can be dominated by corporate actors. When such capacity exists in a more inclusive manner (such as the FSC’s potential change in statutes voted on by members at the General Assembly), these procedures are relatively cumbersome and, when used, do not change the system substantially. This means that the inclusiveness and authenticity of accountability in MSIs are usually low. For instance, when Greenpeace put a motion to the FSC General Assembly to change the requirements for certifications in primeval forests, some corporate actors threatened to leave the FSC (thus leaving the initiative much less impactful), thereby diluting the potential for the rule to protect these types of forests (Arenas et al., Reference Arenas, Albareda and Goodman2020).

DELIBERATIVE MINI-PUBLICS

Before turning to how DMPs could be used to improve the deliberative capacity of MSIs, we first introduce DMPs. They are part of a large and growing family of democratic forums intended to foster public deliberation. Pateman (Reference Pateman2012) highlights four central features of DMPs on which we expand in the following pages: they are initiated or commissioned by a body to deliberate about a particular topic, they are selected through some form of random selection, they include many practices to foster deliberation, and their outputs are compiled and disseminated. Among these features, random selection distinguishes DMPs the most from other deliberative forums (like National Issues Forums, Study Circles, and the 21st Century Town Meetings). Other deliberative forums use one of many other selection techniques, with voluntary self-selection being the most common (Fung, Reference Fung2003). Beyond these central features, DMPs are remarkably versatile in terms of other dimensions, such as size, medium, and decision rule (e.g., Fishkin, Reference Fishkin2009; Paulis, Pilet, Panel, Vittori, & Close, Reference Paulis, Pilet, Panel, Vittori and Close2021).

Initiators and Conveners

A variety of actors play a crucial role in the design, funding, conduct, and outcome of DMPs (Gül, Reference Gül2019). First, one or more actors typically initiate (commission) the DMP and make important decisions about its terms of reference, remit, and output, including civil society and public and executive authorities (Jacquet, Talukder, Devillers, Bottin, & Vrydagh, Reference Jacquet, Talukder, Devillers, Bottin and Vrydagh2020; Setälä, Reference Setälä2017). In some cases, third-party interest groups can be involved in these decisions (Kahane, Loptson, Herriman, & Hardy, Reference Kahane, Loptson, Herriman and Hardy2013).Footnote 4 Although initiators often make critical strategic decisions, they in many cases delegate the actual design and operation of the DMP to a team of independent conveners, such as academics and professional consultancies (Gül, Reference Gül2019; Lang, Reference Lang, Warren and Pearse2008). These tasks often include further specifying the focus of the mini-publics, defining the population and stratification criteria, selecting participants, planning the sessions, and executing the process (Gül, Reference Gül2019). Finally, in some, more institutionalized DMPs, independent commissions can be created and resourced to oversee and implement the process (Knobloch, Gastil, & Reitman, Reference Knobloch, Gastil, Reitman, Coleman, Przybylska and Sintomer2015).

Participant Selection

A first step in selecting participants in a DMP is to define the population. Often this is done based on the population of a particular jurisdiction (e.g., the residents of a particular state), though it can also be more precisely bounded based on the specific focus of the DMP, as in the case of the Citizens’ Jury on waste incineration in Dublin, where the population was defined as those who would be serviced by the focal proposed treatment plant (French & Laver, Reference French and Laver2009). Interest groups, in particular, are often excluded from serving as participants to avoid exerting too much influence over the process but are sometimes granted other opportunities to play a role in the DMP, such as providing information and serving on advisory boards (Carson & Martin, Reference Carson and Martin2002; Kahane et al., Reference Kahane, Loptson, Herriman and Hardy2013; MacLean & Burgess, Reference MacLean and Burgess2010).

Once a target population has been set, participants are selected through some form of random selection. Participants in DMPs can be seen as a particular form of nonelectoral representatives, sometimes termed “citizen representatives,” which are distinct from self-appointed representatives (Urbinati & Warren, Reference Urbinati and Warren2008). They gain much of their legitimacy through their descriptive representativeness (James, Reference James, Warren and Pearse2008; Warren, Reference Warren, Warren and Pearse2008). Descriptive representation can emphasize correspondence in visible characteristics but also in shared experiences, such as one’s professional background (Mansbridge, Reference Mansbridge1999). Regardless of represented characteristics, the initial focus is placed on who the representative is in terms of their correspondence on those characteristics as opposed to what their specific interests or desires are (Brown, Reference Brown2006). In this sense, participants in DMPs do not represent specific constituencies and are not held to account through elections (Brown, Reference Brown2006; Urbinati & Warren, Reference Urbinati and Warren2008).

Descriptive representation has many merits. Pitkin (Reference Pitkin1967) highlights its utility as a means of providing information about those being represented. In her seminal work, Mansbridge (Reference Mansbridge1999) argued that descriptive representation could help increase the substantive representation of disadvantaged groups in two contexts: when the group’s interests are uncrystalized and when there is impaired communication and distrust between dominant and marginalized groups. Goodin (Reference Goodin2008: 248) discusses how aiming for complete mirror representation may be unrealistic but notes how representing “the sheer fact of diversity” could have important benefits, including making decision makers more aware of and interested in soliciting diverse perspectives. At the same time, efforts to foster descriptive representation in DMPs have received some important criticism. First, unlike their formally elected peers, participants in DMPs are neither authorized nor accountable to a particular constituency (Brown, Reference Brown2006). Second, they are also, overall, likely to be less skilled, knowledgeable, and experienced (Mansbridge, Reference Mansbridge1999). Third, what and how groups ought to be represented can be complex and subject to the discretion of organizers (Gül, Reference Gül2019; Mansbridge, Reference Mansbridge1999). The first two challenges are an important reason why many proponents of DMPs see descriptive representation as a complement and not a wholesale substitute for other forms of representation (Mansbridge, Reference Mansbridge1999; Setälä, Reference Setälä2017, Reference Setälä2021). The third challenge points to the importance of reflecting carefully on who ought to have the power to decide on what descriptive characteristics to emphasize.

When it comes to executing the random selection process, there are differences in the specific method of random selection that will have implications for MSIs. Some designs, notably deliberative polls, use a combination of statistical random sampling and a large sample size to select a microcosm of the population in terms of demographic and attitudinal perspectives (Fishkin, Reference Fishkin2018). Statistical random samples are said to give everyone an equal chance of being selected (Brown, Reference Brown2006). Yet, statistical random samples can also be prone to distortions brought on by potential bias in who declines the invitation to participate (O’Flynn & Sood, Reference O’Flynn, Sood, Grönlund, Bächtiger and Setälä2014) or the use of small sample sizes (Bächtiger, Setälä, & Grönlund, Reference Bächtiger, Setälä, Grönlund, Grönlund, Bächtiger and Setälä2014). Other designs use stratified random sampling—often involving oversampling certain groups—to increase the representation of underrepresented groups in the population (Bächtiger et al., Reference Bächtiger, Setälä, Grönlund, Grönlund, Bächtiger and Setälä2014). The use of stratified random sampling helps generate descriptive representativeness across characteristics identified as important for a particular topic (Lubensky & Carson, Reference Lubensky, Carson, Carson, Gastil, Hartz-Karp and Lubensky2013) and thus helps ensure that diverse perspectives are brought into DMPs (Brown, Reference Brown2006). It is important to select stratification criteria deliberately using heuristics like which identity characteristics are most relevant within a particular society and most clearly related to the focus of the DMP (James, Reference James, Warren and Pearse2008).

Deliberation

When it comes to practices to foster robust, well-informed, and inclusive deliberation in DMPs, they commonly include trained and impartial facilitators and moderators, mixing small-group discussions and plenaries (Goodin & Niemeyer, Reference Goodin and Niemeyer2003; Harris, Reference Harris, Elstub and Escobar2019; Landwehr, Reference Landwehr, Grönlund, Bächtiger and Setälä2014; Leydet, Reference Leydet2019). New techniques have been developed to accommodate groups of participants that speak less than others, including encouraging different types of expression and communication and regularly rotating facilitators across different small groups (Curato, Dryzek, Ercan, Hendriks, & Niemeyer, Reference Curato, Dryzek, Ercan, Hendriks and Niemeyer2017; Harris, Reference Harris, Elstub and Escobar2019). Overall, these practices result in DMPs performing well when it comes to their internal deliberations (Setälä & Smith, Reference Setälä, Smith, Bächtiger, Dryzek, Mansbridge and Warren2018). For instance, effective facilitation can help prevent domination by some members, encourage brainstorming, boost interactivity, and track ideas (Carson & Martin, Reference Carson and Martin2002).

DMPs also provide balanced and accessible information on the focal topic, including briefing materials (O’Flynn & Sood, Reference O’Flynn, Sood, Grönlund, Bächtiger and Setälä2014), expert testimony and presentations (Brown, Reference Brown2006), and information from third parties, such as relevant interest groups, that complements expert information (MacLean & Burgess, Reference MacLean and Burgess2010). This helps participants transition from having a “raw” to a “refined” opinion on the topic, one that “has been tested by the consideration of competing arguments and information conscientiously offered by others who hold contrasting views” (Fishkin, Reference Fishkin2009: 14). It also helps contribute to the inclusion of a broader array of relevant discourses in tandem with the descriptive representation of participants (Felicetti et al., Reference Felicetti, Niemeyer and Curato2016). The use of random selection enables participants to engage with this information in a more impartial and open-minded manner than if they were selected through other selection methods, such as elections (e.g., having to fulfill electoral promises), contributing to higher-quality decision-making (Gastil & Wright, Reference Gastil and Wright2018; Vandamme & Verret-Hamelin, Reference Vandamme and Verret-Hamelin2017). In the case of randomly selected deliberators in a citizens’ jury focused on container deposit legislation, they found that “the citizens in this case study showed no sign of susceptibility to outside pressure and they displayed no obvious biases or preconceptions that inhibited rational deliberation” (Carson & Martin, Reference Carson and Martin2002: 13).

Outputs

Following the deliberation phase, DMPs enter a decision-making phase to consolidate conclusions ahead of their dissemination. DMPs vary in terms of how decisions are made. Some strive for a form of consensus, whereas others use voting and individual surveys (Escobar & Elstub, Reference Escobar and Elstub2017; Fishkin, Reference Fishkin2009). These conclusions are then compiled (e.g., in a position report) and diffused to the broader public (Fournier, van der Kolk, Blais, & Rose, Reference Fournier, van der Kolk, Blais and Rose2011). Initiators have a significant amount of power in deciding what the outputs of DMPs will be and how they will be used (Setälä, Reference Setälä2017). For DMPs focused on informing policy, the outputs of DMPs are often consultative. However, in rare cases, initiators can have some more direct influence and authority (Setälä & Smith, Reference Setälä, Smith, Bächtiger, Dryzek, Mansbridge and Warren2018), such as when political actors commit to implementing a DMP’s suggestions (Fishkin, He, Luskin, & Siu, Reference Fishkin, He, Luskin and Siu2010).

Deliberative Mini-Publics in Deliberative Systems

In light of these unique characteristics, DMPs have attracted significant attention in research on deliberative systems (e.g., Curato & Böker, Reference Curato and Böker2016; Felicetti et al., Reference Felicetti, Niemeyer and Curato2016; Hendriks, Reference Hendriks2016; Niemeyer & Jennstål, Reference Niemeyer, Jennstål, Bächtiger, Dryzek, Mansbridge and Warren2018). Scholars have developed frameworks focused on the tasks and responsibilities DMPs could undertake in various polities (e.g., Goodin & Dryzek, Reference Goodin and Dryzek2006). Some of this work examines how DMPs could be used in specific parts of the deliberative system (see, e.g., Dryzek, Reference Dryzek2009, for their use in the public space; Felicetti, Reference Felicetti2014, for their use as a means of transmission). In a related area of research, scholars have explored, directly and indirectly, how the use of DMPs can contribute to the deliberative capacity of deliberative systems. For instance, Lafont (Reference Lafont2017, Reference Lafont2020) outlines various ways DMPs could revitalize public deliberation in a more participatory manner. Finally, in another stream of research, scholars have adopted a goal-oriented perspective on the uses of different types of DMPs, whereby they may be more or less suitable in different contexts and to solve different types of problems in particular systems (Curato, Vrydagh, & Bächtiger, Reference Curato, Vrydagh and Bächtiger2020).

DELIBERATIVE MINI-PUBLICS IN MULTI-STAKEHOLDER INITIATIVES

We now theorize how DMPs can be translated to the context of MSIs by elaborating on four key design parameters. We then develop theory about how five different uses of DMPs can contribute to improving MSIs’ deliberative capacity.

Design Parameters

As elaborated on earlier, DMPs were developed for, and have almost exclusively been used in, the context of polities like nation-states or municipalities. However, MSIs differ from these polities substantially in terms of membership, processes, structure, and decision-making institutions (i.e., empowered space). Moreover, MSIs also vary extensively among themselves. These features necessitate careful reflection about how DMPs are to be structured and implemented in MSIs. While some DMPs’ characteristics, structures, and processes can be readily translated to MSIs (e.g., using trained moderators and facilitators), other aspects need more careful and specific consideration (e.g., defining the population from which to draw participants). We conceptualize four design parameters we see as particularly relevant to translating DMPs to MSIs.

Initiating and Convening Deliberative Mini-Publics in Multi-Stakeholder Initiatives

In terms of the initial impetus to adopt DMPs in the first place, there are two possible scenarios. In the first case, it could happen at the time of the founding and elaboration of an MSI, as national governments and the nonprofit sector (Bartley, Reference Bartley2007; Marques & Eberlein, Reference Marques and Eberlein2020) can serve as key instigators. In the second case, it could happen after the founding of the MSI, as would be the case for the large variety of existing MSIs, for instance, as a result of a motion by one or more MSI members.

Specific decisions about a DMP’s initiation, whether one-off or ongoing, can be made by a dedicated, independent commission based on predefined parameters (Knobloch et al., Reference Knobloch, Gastil, Reitman, Coleman, Przybylska and Sintomer2015). In the case of the FSC, a related MSI secretariat, such as the Marine Stewardship Council (dealing with sustainable fishing), could serve as such a body. This independent commission could include MSI members in an advisory capacity to seek their input on the remit and output to legitimize the DMP, increase buy-in, and leverage members’ insights in the process (French & Laver, Reference French and Laver2009; Kahane et al., Reference Kahane, Loptson, Herriman and Hardy2013).

In terms of convening DMPs, MSIs may be susceptible to subtle co-optation or domination from powerful actors who may, for instance, advocate for preferred venues or times for deliberations (Maher, Reference Maher2022). Best practice from DMPs indicates that such co-optation can be reduced by appointing neutral conveners (e.g., with no conflict of interest with the issue[s] at hand) to design and implement the DMPs (Beauvais & Warren, Reference Beauvais and Warren2019). The independent commission described before could also serve the role of convener.

Defining the Population

DMPs have been developed for the most part in the context of a clearly delimited sovereign territory (although there are a few exceptions, such as those focused on governing the use of the internet; see Fishkin et al., Reference Fishkin, Senges, Donahoe, Diamond and Siu2018). Even then, it can be difficult to delineate clearly who is sufficiently affected by a particular decision to warrant inclusion (O’Flynn & Sood, Reference O’Flynn, Sood, Grönlund, Bächtiger and Setälä2014). Some citizens may be legally bound by a decision, others may be directly affected, and still others might be indirectly affected.

MSIs face an even greater issue regarding which actors to include in the population given that they span national boundaries and their main constituents are not citizens but mostly organizations, such as corporations or NGOs (Martens et al., Reference Martens, van der Linden and Wörsdörfer2019). In terms of the overall population of DMPs when used in the context of MSIs, drawing on Martens and colleagues’ (Reference Martens, van der Linden and Wörsdörfer2019) categorization of different actors involved in MSIs, we take as the focal population of actors (individuals and organizations) the combined group of MSI members, rule takers (i.e., firms), and all otherwise affected actors. Importantly, as we discussed earlier, consideration of the scope of a DMP is crucial when defining the population (French & Laver, Reference French and Laver2009). For instance, in the case of the FSC, a DMP addressing a more specific issue related to sustainable forest management, such as FSC’s Principle 3, “Indigenous Peoples’ Rights,” would have a more narrow population. This is because not all actors from the population of the FSC will be affected by issues related to Indigenous people (such as firms exploiting forests with no Indigenous communities). Moreover, Indigenous notions of sovereignty and self-determination (Banerjee, Reference Banerjee2021) will also be important in determining the population of such an issue-focused DMP.

Following Bader (Reference Bader2018), decisions around the population of a DMP in an MSI are best not based on an initial drawing board but made deliberatively by conveners and, when necessary, expert advisors given the issue and techniques like stakeholder mapping. It is important to recognize that defining who is affected by a particular topic is context-dependent and may be challenging and, in the case of MSIs, may be the result of manipulation and power dynamics (Brown & Dillard, Reference Brown and Dillard2013; Dawkins, Reference Dawkins2021). We later discuss how DMPs could be used to support this process when discussing meta-deliberation in MSIs.

Delineating and Selecting Participants

Once the population is defined, a second decision pertains to which actors will be invited and how they will be selected. The first question pertains to who should be excluded, which is particularly important given the differentials of power between actors in MSIs (Dawkins, Reference Dawkins2021; Taylor, Reference Taylor2005). While a full examination of exclusion criteria is beyond the scope of our article and, in any case, will depend on each DMP, we discuss the important consideration of official representatives of organizational members of MSIs (e.g., the CEO of IKEA, the president of the WWF). We think it is important to exclude them from participating in DMPs as participants to avoid biasing the process, but argue that they should be granted roles commonly given to interest groups in DMPs, such as the opportunity to testify and the opportunity to help inform the information that goes out to participants (e.g., Carson & Martin, Reference Carson and Martin2002). This approach will have the benefits of gaining access to their knowledge and perspectives and increasing their buy-in while helping to reduce the risk that they will dominate or derail the actual deliberations (Kahane et al., Reference Kahane, Loptson, Herriman and Hardy2013).

Second, in terms of which actors can be invited as participants of DMPs, MSIs are unique in that some actors of the population will be formal organizations (e.g., corporate rule takers) made up of individuals (e.g., employees), whereas others will be individuals or informally organized individuals (e.g., local community members). In this light, we envision three main options. First, at one logical extreme, only individuals would be involved in the DMP, with all organizations being disaggregated so that the individuals working for them become individuals of the population (for such a use in the case of a DMP for the governance of the internet, see, e.g., Fishkin et al., Reference Fishkin, Senges, Donahoe, Diamond and Siu2018). In the context of the FSC, this would mean that FSC organizational members, like IKEA or the WWF, would see each of their employees (from a senior marketing manager to the janitor in a store to a research associate) be potential participants in the same vein as local community or Indigenous individuals. Yet, this approach carries the risk that large organizations (in particular, corporations) would represent a larger piece of the pie of the composition of the DMP. Second, at the other logical extreme, individuals and organizations could both be treated as single actors. This would increase the likelihood that individuals would be selected and, in so doing, decrease the relative weight of organizations (see, e.g., Gleckman, Reference Gleckman2018, who discusses such a possibility applied to MSI governance). In the case of the FSC, organizations like IKEA and unions would each have one randomly selected member eligible as a potential participant, and each of the Indigenous people living in FSC-related forests would count as one potential participant. Third, a hybrid approach could be used, whereby a multiplier would be used to grant organizations a number of potential participants based on their size. In this way, individuals would be the only actors who can serve as participants of the DMP, but there would be comparatively more participants from organizations due to the multiplier. Home Depot (one of the largest firms participating in the FSC) could, for instance, be granted twenty employees as potential participants. Although each approach has its unique pros and cons, all of them would help rebalance the power from large organizations toward dispersed and unorganized but numerous actors—which is often the case of marginalized stakeholders (e.g., Banerjee, Reference Banerjee2018).

As discussed earlier, participants do not serve as delegates of any constituency; rather, grounded in the principles of descriptive representation, they “stand for” the broader population as themselves. For instance, in the case of internet governance, participants represented the broader population of users of the internet, not the organizations with which they were affiliated (Fishkin et al., Reference Fishkin, Senges, Donahoe, Diamond and Siu2018). Participants deliberated “as netizens, changing their views based on substance rather than simply taking instruction from their home institutions” (Fishkin et al., Reference Fishkin, Senges, Donahoe, Diamond and Siu2018: 12–13). Despite prior evidence, some participants may be inadvertently influenced by their organizational affiliation, making the aforementioned practices to foster robust deliberation all the more important. Additional techniques to overcome this include anonymizing proceedings to reduce the perceived risk of retribution (Carson & Martin, Reference Carson and Martin2002) and using secret votes (if voting is used) to reduce the risk of retribution (Gastil & Wright, Reference Gastil and Wright2018). Even if some participants cannot overcome their organizational affiliations, random selection can help ensure they would be a minority and would pose less disruption to deliberations (Leydet, Reference Leydet2019). For these reasons, while recognizing these potential risks, they are surmountable and unlikely to significantly detract from the main benefits offered by DMPs in MSIs.

Third, we illustrate what the sampling process to select participants could look like. We apply the first option from earlier, whereby all organizations would be disaggregated into their respective individuals. The pool of potential participants would thus comprise all individuals and employees of organizations that are members of the MSI, rule takers, or otherwise affected (excluding any individuals ultimately subject to exclusionary criteria). As described earlier, two main methods could then be used to select participants in the DMP from this population: statistical random sampling and stratified random sampling. The methods and stratification criteria should be made with the support of impartial, expert conveners based on the broader principles of representative characteristics within the population and the goal of the DMP (James, Reference James, Warren and Pearse2008). For example, for the purpose of illustration, stratification criteria in the case of a DMP tasked with input on the FSC rules could be sector (public, for-profit, and nonprofit organizations; general public), position in the supply chain (upstream vs. downstream), and views about the place of humankind in nature (e.g., anthropocentric vs. ecocentric; Purser, Park, & Montuori, Reference Purser, Park and Montuori1995).

Efforts to Increase Willingness to Participate and Support

It is essential to ensure that all actors invited to participate in the DMP are willing and able to do so. Given the unique nature of MSIs, different approaches are likely to be necessary for different types of actors, such as for-profits and related actors (e.g., industry associations), nonprofits, and loosely or unorganized actors (e.g., local communities, natural environment). In terms of the latter two, though research suggests that nonparticipation is complex and multifaceted (Jacquet, Reference Jacquet2017), some suggestions have been developed to increase participation, such as honoraria or covering participation-related expenses (e.g., accommodation) (Harris, Reference Harris, Elstub and Escobar2019). Given that an important reason for not participating is a lack of perceived impact of the DMP, conveners can clearly spell out how the outputs of the DMP will be used within the MSI deliberative system (Jacquet, Reference Jacquet2017). French and Laver (Reference French and Laver2009) found that the possibility of having input into decision-making was perceived by participants as an important incentive. In the context of MSIs, however, and as heavily emphasized in the research critical of them (e.g., Banerjee, Reference Banerjee2018; MSI Integrity, 2020), actors other than for-profits are often sidelined in decision-making processes. Some actors may also refuse altogether to participate in such deliberations in the first place because of intractable differences, such as some Indigenous communities’ emphasis on self-determination (Banerjee, Reference Banerjee2021). Yet, apart from intractable differences, being excluded from MSIs should, in general, be sufficient motivation for marginalized groups to participate in DMPs that would be able to influence MSI processes and decisions and make them less marginalizing. Some marginalized groups may require additional support to be able to participate that DMPs can provide, such as supplementary learning materials (O’Flynn & Sood, Reference O’Flynn, Sood, Grönlund, Bächtiger and Setälä2014). Yet, as we describe later, DMPs can also help build the skills and capacities of participants and nonparticipants (Niemeyer, Reference Niemeyer, Grönlund, Bächtiger and Setälä2014) so that they could address how and why these groups have been marginalized in the first place in the MSI. In the spirit of reciprocity core to authentic deliberations, DMPs allow participants to learn from each other despite differing worldviews (Caluwaerts & Kavadias, Reference Caluwaerts, Kavadias, Grönlund, Bächtiger and Setälä2014).

Finally, it is also important to consider how to encourage corporate members of MSIs to support the adoption of DMPs. Research on the involvement of interest groups in DMPs suggests various techniques like conveying that DMPs may be just one part of a broader decision-making process and that their interests will also be formally represented in other ways in MSIs (e.g., being a member of the assembly, participating in the election of the MSI board), offering them the chance to provide feedback on the DMP after its completion, and emphasizing the organizational learning benefits of participating (Kahane et al., Reference Kahane, Loptson, Herriman and Hardy2013). Additionally, prior work on MSIs points to several factors that could similarly increase corporate support for DMPs, including market rewards like certifications (Potoski & Prakash, Reference Potoski and Prakash2009); managerial or supply chain advantages, such as improved traceability (Zadek, Reference Zadek2004); lock-in effects of participation therein (e.g., Bartley, Reference Bartley2007; Fransen, Reference Fransen2012); reputational sanctions stemming from pressure from activist groups (Mena & Waeger, Reference Mena and Waeger2014); and high-publicity events. For instance, Huber and Schormair (Reference Huber and Schormair2021) forcefully show how the 2013 Rana Plaza collapse coerced some firms to participate in the Accord on Fire and Building Safety, an MSI in Bangladesh focused on improving working conditions in the textile industry. This did not prevent some conservative firms from maintaining their reluctant stance toward MSI regulation and collaboration with stakeholders, but some showed a willingness to engage over time (Huber & Schormair, Reference Huber and Schormair2021).

Improving Multi-Stakeholder Initiatives’ Deliberative Capacity through Deliberative Mini-Publics

We now develop a framework of how DMPs can improve the deliberative capacity of MSIs. In line with recent goal-oriented perspectives on the use of DMPs (Curato et al., Reference Curato, Vrydagh and Bächtiger2020), MSIs should make decisions about which uses are more relevant based on undertaking a comprehensive evaluation of their deliberative capacity. We conceptualize five uses of DMPs corresponding to each element of the MSI system: public space, empowered space, transmission, accountability, and meta-deliberation. Our conceptualization details how each use can improve the deliberative capacity for that element and the MSI system as a whole.

While we conceptualize how each use of DMPs uniquely improves deliberative capacity depending on the characteristics of the system’s element, we also identify effects that span all our uses. In terms of their effects on the deliberative capacity of the system’s elements, DMPs can improve inclusiveness and authenticity. When it comes to inclusiveness, the use of a DMP can overcome deficiencies in the breadth of interests and discourses spreading in a particular element of the system. As discussed earlier, the use of random selection helps bring together a descriptively representative body to ensure that a broader array of perspectives and interests are brought to bear on deliberations in the element, and the careful provision of balanced and comprehensive information that covers relevant arguments and discourses would help ensure that relevant discourses are included in these deliberations (Carson & Martin, Reference Carson and Martin2002; Dryzek, Reference Dryzek2010; Felicetti et al., Reference Felicetti, Niemeyer and Curato2016). The use of DMPs can also improve authenticity in a particular element of the system through “deliberation-making” (Niemeyer, Reference Niemeyer, Grönlund, Bächtiger and Setälä2014: 179). DMPs’ myriad practices to foster deliberation equip and enable participants to carefully reflect on, parse, and synthesize various arguments, discourses, and sources of information, such as carefully scrutinizing potentially manipulative discourses (Curato & Böker, Reference Curato and Böker2016; Niemeyer, Reference Niemeyer, Grönlund, Bächtiger and Setälä2014; Niemeyer & Jennstål, Reference Niemeyer, Jennstål, Bächtiger, Dryzek, Mansbridge and Warren2018). This can improve the quality of deliberations outside the DMP if the takeaways are synthesized in a manner that is understandable to the broader MSI population, as defined earlier (Niemeyer, Reference Niemeyer, Grönlund, Bächtiger and Setälä2014). We tailor these two effects that span our uses to each use in what follows.

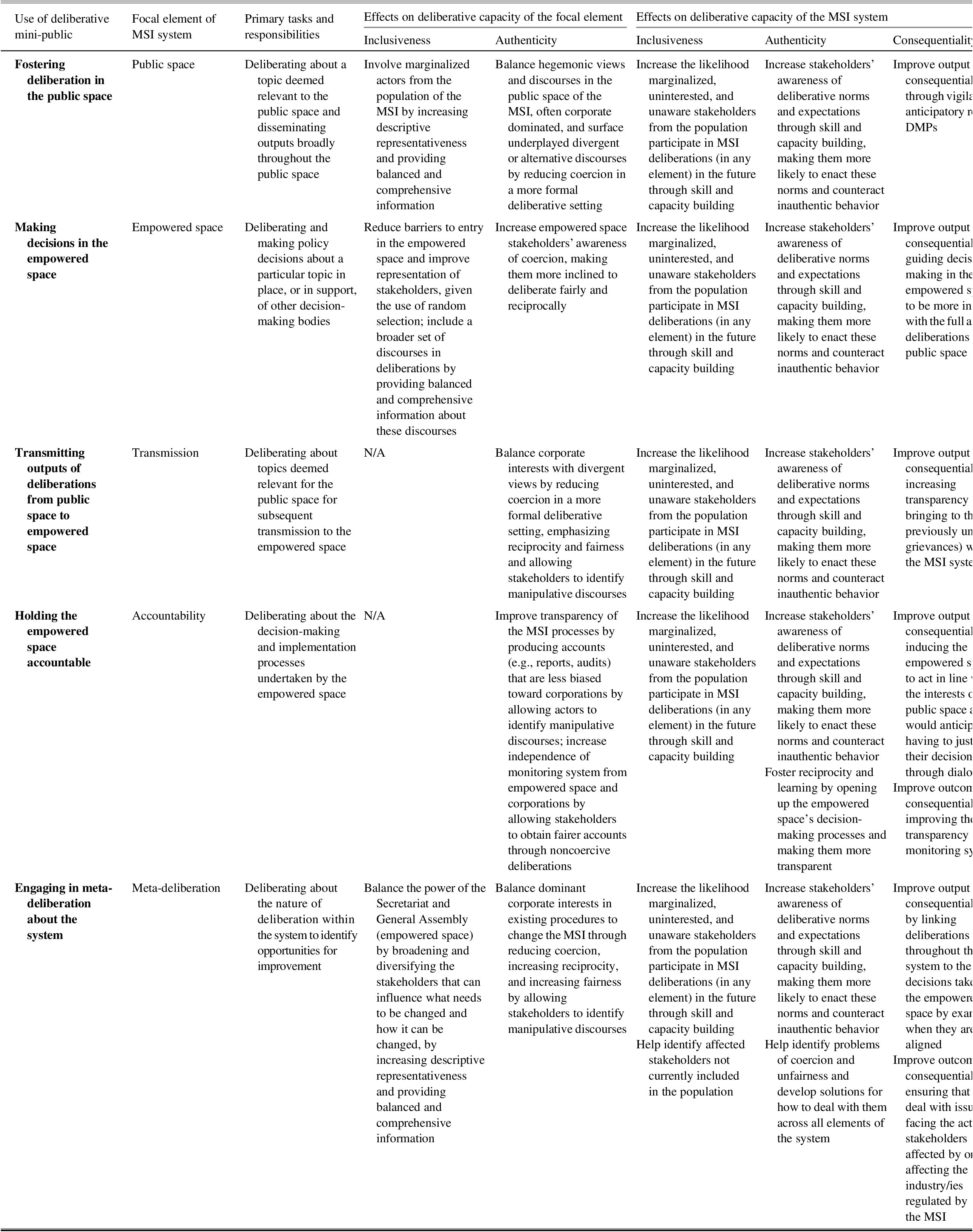

One effect spans all our uses of DMPs to improve the deliberative capacity of the system as a whole. DMPs can improve system-wide inclusiveness and authenticity through fostering deliberative skill and capacity building (Niemeyer, Reference Niemeyer, Grönlund, Bächtiger and Setälä2014), by which they “contribute to building the capacity of a polity to host inclusive and authentic deliberation” (Curato & Böker, Reference Curato and Böker2016: 178, emphasis original). Those who participate directly in DMPs have the opportunity to develop numerous civic capacities and habits (Knobloch & Gastil, Reference Knobloch, Gastil, Carlson, Gastil, Hartz-Karp and Lubensky2013, Reference Knobloch and Gastil2015). Yet, even those who do not participate directly can see their skills and capacities develop through the spillover of deliberative norms and broader cultural change brought about through well-executed DMPs (Boswell, Hendriks, & Ercan, Reference Boswell, Hendriks and Ercan2016; Niemeyer, Reference Niemeyer, Grönlund, Bächtiger and Setälä2014). In MSIs, by building their deliberative skills and capacities, DMPs can increase the likelihood marginalized, uninterested, or unaware actors from the population participate in MSI deliberations (in any element), thereby improving inclusiveness. They can also improve authenticity by increasing actors’ ability to enact deliberative norms and expectations and challenge acts of coercion, unfairness, and imbalance. We now turn to an overview of each of our five proposed uses of DMPs. We summarize our main arguments in Table 2.

Table 2: Uses of DMPs in MSIs and Their Effects on Deliberative Capacity

Our first use posits DMPs as a means of fostering deliberation in the public space of the MSI. Such a DMP could focus on any topic deemed relevant to the population of the MSI and would disseminate its outputs and underlying arguments broadly throughout various sites of the MSI’s public space. The Citizens’ Initiative Review is a useful example given its focus on distributing its outputs pertaining to ballot measures to the broader public to inform their decision-making (Knobloch et al., Reference Knobloch, Gastil, Reitman, Coleman, Przybylska and Sintomer2015). This use is well suited to overcoming the aforementioned deficiencies in inclusiveness and authenticity that sometimes afflict an MSI’s public space. By bringing together a descriptively representative group of actors from the population of the MSI, it would improve the inclusiveness of the public space of an MSI by surfacing additional voices and opinions. In the case of the FSC, such a DMP would include various stakeholders from which participants can be drawn, some of which are not included in the General Assembly of the FSC, such as some social or environmental stakeholders from some African or Southeast Asian countriesFootnote 5 who may not be members due to a lack of knowledge about the FSC or the inability to pay membership fees. It would also bring alternative discourses to the table, which is often dominated by powerful actors like corporations, by providing balanced information on relevant arguments—the “contestatory” use of DMPs that Lafont (Reference Lafont2017, Reference Lafont2020) outlines. This use would also improve the authenticity of deliberations in the public space by formalizing them and providing a forum in which coercion may be less present than in more natural deliberative settings. Indeed, fairer deliberations stemming from using a DMP could allow less powerful, often noncorporate actors to push against the hegemonic view(s) in the public space. In the case of the FSC, this hegemonic view is that self- and private regulation can limit deforestation through market means with limited state intervention (Moog et al., Reference Moog, Spicer and Böhm2015). Because not all conversations in the public space of the FSC (see, e.g., FSC Watch website) follow this hegemonic view, a DMP could help bring alternative views to the fore and confront the hegemonic view(s) by, for instance, putting these views under scrutiny.

This use can also contribute to improving the deliberative capacity of MSIs at the system level. The effects on deliberative capacity through skill and capacity development could be particularly powerful in this use, given the emphasis on broad-based dissemination throughout the public space. In terms of output consequentiality, this use could help mobilize various sites in the public space to more directly scrutinize and engage with the empowered space on perceived issues and concerns with the MSI. This corresponds to Lafont’s (Reference Lafont2017, Reference Lafont2020) vigilant and anticipatory roles of DMPs, in which the MSI’s decisions and processes do not match views in the public space and when actors of the public space have not yet formed opinions about these issues, respectively. By making the gap between the public and empowered spaces evident and making explicit some issues with the MSI for various sites in the public space, this use would strengthen the link between deliberations in the public space and decisions in the MSI, ultimately improving system-wide output consequentiality.

Our second use posits DMPs as a means of making decisions in the empowered space of the MSI, with or without binding decision-making authority. In the case of the former, this use would be particularly useful for topics with which the existing empowered space is ill suited to deal, especially when there are conflicts of interest or a lack of motivation to address important issues (Bouricius, Reference Bouricius2018; Kuyper & Wolkenstein, Reference Kuyper and Wolkenstein2019). For example, the FSC’s empowered space was conflicted around protected forests (“intact forest landscapes”), and the General Assembly eventually decided to push this issue aside to move on to other problems and decisions (Arenas et al., Reference Arenas, Albareda and Goodman2020). In such a case, a DMP could take over authority from the general assembly to help move forward on this value-laden, contested issue. A variant of this proposed use with less decision-making authority could build off proposals for permanent chambers comprising randomly selected representatives (e.g., Gastil & Wright, Reference Gastil and Wright2018). For example, one such chamber could have the “power of initiative, consultation, and amendment” (Vandamme & Verret-Hamelin, Reference Vandamme and Verret-Hamelin2017: 20). In the case of the FSC, the Board of Directors established a Policy and Standards CommitteeFootnote 6 that fulfills this role. A DMP could replace or complement this committee, which provides recommendations to the Board of Directors on value-laden decisions.

This use of a DMP could improve authenticity and inclusiveness in MSIs’ empowered space. DMPs are well suited to overcoming deficits to authenticity, such as bargaining, horse trading, and politicking, that can influence decisions in empowered spaces (Kuyper & Wolkenstein, Reference Kuyper and Wolkenstein2019). The relatively fairly structured general assembly of the FSC could benefit from such use, as some interests have nevertheless been favored in decisions (Dingwerth, Reference Dingwerth2008; Moog et al., Reference Moog, Spicer and Böhm2015). Moog and colleagues detail, for instance, the strategic struggle within the FSC in its early years between proponents of radical, high ecological integrity and those favoring a market approach based on consumer recognition and a large market share for FSC-certified products, which won the battle. This use of a DMP could help rebalance interests by increasing the fairness and reciprocity of, as well as limiting coercion in, deliberations through their contributions to deliberation making (e.g., participants becoming more aware of manipulative discourses). In terms of inclusiveness, barriers to entry in the empowered space could be reduced by this use. Through the use of random selection, stakeholders from the population that are not currently formally involved in the empowered space could now be included. In the same vein, this would solve some problems with representation through self-appointed third parties in MSIs (Reinecke & Donaghey, Reference Reinecke and Donaghey2021) by representing stakeholders directly and in a descriptively representative manner. Once these stakeholders are included, this use would also foster a broader inclusion of discourses by stakeholders through balanced and comprehensive information.

This use can also contribute to improving the deliberative capacity of MSIs at the system level. As with other uses, it can contribute to participants’ and nonparticipants’ skill and capacity development, particularly in the case of members of the empowered space who can gain new perspectives about how their work could be approached. This use would also improve the output consequentiality of the MSI system by guiding decision-making in the empowered space to be more in line with the full array of deliberations in the public space. Indeed, the empowered space of MSIs usually consults stakeholders other than only their members when deciding on or changing their processes. For instance, the FSC regularly puts its policies, standards, and procedures to external consultation when developed or revised.Footnote 7 A DMP would help bring a broader set of views from the public space in such consultative processes and ultimately link the empowered space’s decisions to some suggestions made by stakeholders.

Our third use posits DMPs as a means of transmitting outputs of deliberations from the public space to the empowered space of the MSI. Such a DMP can provide input to the assembly, board, and other bodies of the empowered space of the MSI about what issues ought to be pursued and how they could be pursued. This input could include what items to put on the agenda, feedback on proposed rules, and feedback on which members should be included in the MSI in the first place. In this way, they would function as “mediating institutions” (Parkinson, Reference Parkinson, Parkinson and Mansbridge2012: 162) that could overcome deficiencies in the transmission of informed opinions and ideas from the public space to the decision-making bodies in the empowered space (Boswell et al., Reference Boswell, Hendriks and Ercan2016; Hendriks, Reference Hendriks2016).