White Mississippians’ suspicions of Negro plots and machinations swarmed like locusts around Minnie Geddings Cox as she stepped off the train. Cox had arrived back home in Indianola, Mississippi, on a warm afternoon in February 1904. Cox had been the African American postmistress of the town until threats against her life forced her to escape from Indianola shortly after New Year's Day in 1903.Footnote 1 After a year spent exiled in Birmingham, Alabama, she felt it safe to return home. She may have wondered that she miscalculated her timing given the orgy of bloodletting that greeted her return. One dead white man. Six dead Negroes in retaliation: three women and three men. Only a day or so before Cox arrived home, a crowd of about one thousand men, women, and children had looked on as its members beat, tortured, and then burned to death sharecropper Luther Holbert and his common-law wife Mary in nearby Doddsville. A lynch mob led by Indianola lawyer and future district attorney Woods Eastland had chased the desperate couple across four counties in as many days before the mob caught them hiding on a plantation in LeFlore County. Some newspapers set the Eastland mob's numbers at five hundred. During the course of the hunt, the mob shot and wounded two women, murdered two women, and slaughtered two men it mistook for Holbert. Many white Sunflower County residents suspected that a number of African Americans had aided the couple, which helped explain how Holbert and Mary had been able to evade Eastland's mob for so long.Footnote 2

Minnie Geddings Cox and her husband Wayne W. Cox—both educated, property-owning, middle-class African Americans—were spared Holbert's and Mary's brutal fate. The Coxes survived their ordeal with the angry white Indianolans. Survival, however, can be a relative term. For nearly two years, Minnie Cox found herself equally vulnerable to the terrifying atmosphere of extralegal racial sexual violence and intimidation designed to keep African Americans in their place in the early twentieth-century Mississippi Delta. The Coxes’ ordeal made clear that well-to-do African Americans who may have believed their achievements insulated them from extralegal violence and whitecapping did so at their own peril; material success could prove a thin shield. The Coxes’ education, wealth, and social standing had not protected them from the threat of lynching, which claimed the lives of Holbert, Mary, and thousands of other Black men and women who threatened the system of Jim Crow. Violence shaped well-to-do Afro-Mississippians’ responses to, and their options within, that system.Footnote 3

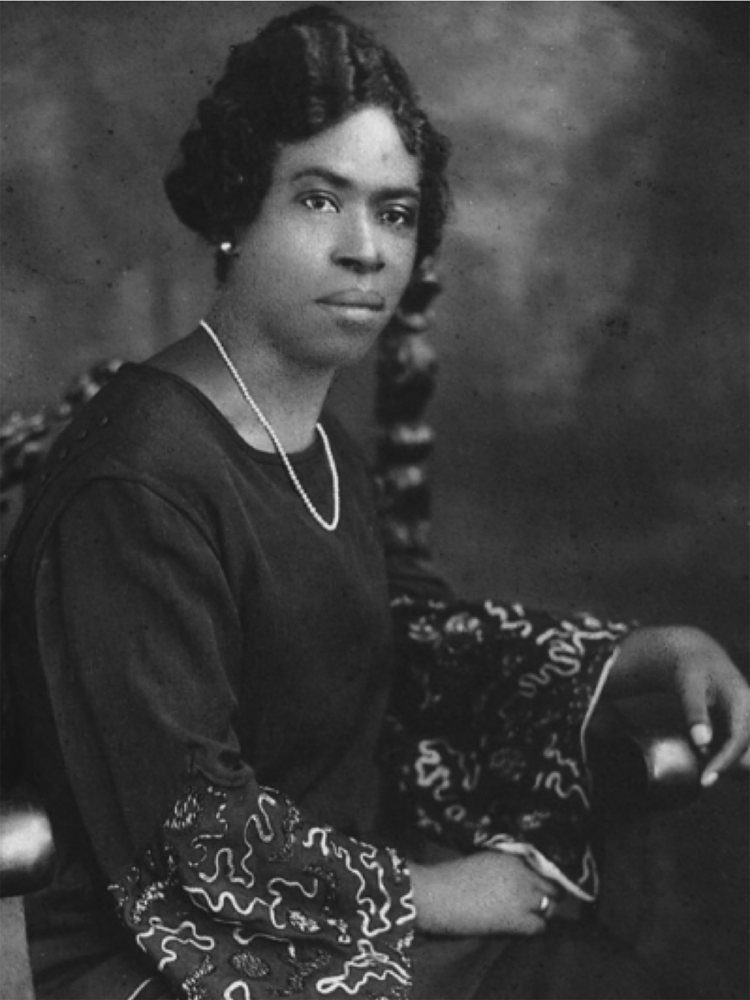

Cox hardly returned to the good graces of the white community in Indianola (see Figure 1). As whites speculated about the ways African Americans had conspired to aid and protect Holbert and Mary, they should have considered the ambitious plots of Cox, her husband Wayne, and several other prominent African Americans in the Delta and throughout Mississippi. In October 1904, Governor James K. Vardaman signed Wayne Cox's charter for the Delta Penny Savings Bank, the third chartered Black-owned bank in Mississippi and among the first dozen Black banks organized in the United States. The Delta Penny opened its doors in January 1905.Footnote 4

Figure 1. Minnie Cox, ca. 1900. (Source: Philip Rubio, There's Always Work at the Post Office: African American Postal Workers and the Fight for Jobs, Justice, and Equality [Chapel Hill, 2010], 24.)

Had it not been for the Indianola Affair, the Coxes may never have considered organizing a bank. Some years after opening the Delta Penny, Wayne Cox described it and other Black-owned banks and businesses in the state as “monuments of protest to the injustices inflicted upon him and his wife” during the incident that national newspapers described as the Indianola Affair.Footnote 5 In the span of about six years, those monuments grew to include twelve Black-owned banks in Mississippi, more than in any other state.Footnote 6 Dr. Edward W. Lampton of Greenville, a minister and businessman, spoke boldly about the flowering of Black finance and enterprise in Mississippi. Lampton invoked Minnie Geddings Cox's ordeal when he declared in 1905 that “Governor Vardaman and all the other devils this side of Hades cannot stay this [emphasis added] kind of prosperity.”Footnote 7

The kind of prosperity that Lampton referred to highlights the core mission of enterprising early twentieth-century African Americans—economic development and job creation—and represents not only a response to but also a bulwark against Jim Crow between 1900 and the Great Depression, a period historian Juliet E. K. Walker marks as the “golden age of Black business.” Banks represented a practical riposte to efforts to block African American progress through extralegal violence, strict segregation, denial of education, and economic repression. Similar to bankers in small towns, Black bankers and bank board members also exercised important roles in civic affairs and community life. Barred from formal political office by the turn of the twentieth century, they still played important civic roles as spokespersons for their communities with the local white civic-business elite. In one of their most radical roles, Black banks provided a much-needed source of credit for economically vulnerable Black communities, especially cash-strapped farmers who owned their own land or worked on other people's land as tenant farmers and sharecroppers.Footnote 8

Financial institutions controlled by African Americans complicate notions of accommodation and protest that still hold sway in characterizations of early twentieth-century Black political thought. Given the civic, economic, and cultural roles that Black bankers played in the first three decades of the twentieth century, the realms of banking and finance reveal a complex approach to citizenship, activism, and resistance. Black banks drew their leadership and largest contributors from a pool of ambitious upstarts as well as successful farmers, large property holders, entrepreneurs, and professionals. These enterprising African Americans’ strategies expressed a broad spectrum of responses that also drew from equally diverse sets of motivations, from the purely profit driven to civic-focused institution building and community development to outright demands for political and social equity. In practice, their strategies often melded, reflecting more of a “both/and” than an “either/or” orientation to citizenship. They considered personal ambition and profit not as mutually exclusive from communal empowerment and uplift but as essential to accomplishing both. They advanced a layered citizenship that included self-determination and control of Black communities at its center, through which they could engage in civic life even without the franchise.Footnote 9

To be sure, economic self-interest and a desire to consolidate political power reveal that these enterprising men and women certainly muddled the personal and the communal. For Black bankers in particular, these “Negro captains of finance” stressed their roles as community leaders and emphasized economic power as an essential component of that leadership. It is also critical to note that the thousands of small farmers, laborers, skilled artisans, domestics, and other working-class people who purchased stock in and entrusted their money to these banks also envisioned economic autonomy as an essential factor in their claims on the privileges of citizenship. Breaking the grip of the crop-lien system, increasing land and property ownership, and building wealth represented important priorities for Black communities, priorities that held larger political import under the pall of Jim Crow. The presence of, or at least access to, a Black bank broadened the economic and political possibilities available to African Americans in the early twentieth-century South.

The larger import of these financial monuments of protest was not lost on white Southerners in general or white Mississippians in particular. They expressed an equally complex array of reactions to Black banks that vacillated between paternalistic acceptance, bureaucratic harassment, economic exploitation, and extralegal racial sexual violence. African Americans met Jim Crow law, demeaning social etiquette, and extralegal state and private racial sexual violence with renewed commitments to self-determination. Enterprising Afro-Mississippians, then, did not merely concede ground to white supremacists. They embraced a vision of Black self-determination that linked community building with the kind of economic prosperity that Lampton extolled as a force so dynamic and inexorable that even the most determined white supremacists in Mississippi could not wend its flow.Footnote 10

Lampton, however, underestimated the power of a new tool in their arsenal: the Mississippi Banking Law of 1914. The white business-civic elite had some sense of the far-reaching implications that the proliferation of Black banks portended. Whites’ anxieties melded in a peculiar alchemy of progressive zeal and white supremacy that professed the idealistic goal of protecting citizens from unscrupulous individuals and exploitative business practices but had the practical effect of destroying symbols of African American economic and social progress. Politicians and bureaucrats bent crass, racial supremacist ideology to the more palatable rhetoric of progressive reform. The context that drove the opening of Black banks as “monuments of protest” during the first decade of the twentieth century also made the new banking law a powerful tool with which state actors and even regular citizens could strike blows against these perceived threats.

In addition to the growing number of Black-owned financial institutions, particularly banks and insurance companies, those threats included Black men's continued political influence in the Republican Party, which, despite widespread disenfranchisement, accorded Black men a say over patronage in the state and a voice in national presidential elections. More important, Black-owned financial institutions offered Afro-Mississippians access to credit, mortgages, savings, and death and sick benefits beyond the control of the white power structure. Because of the close interdependence among Black financial institutions, regulators could strike a devastating and far-reaching blow against Black people's challenges to Jim Crow.

“The Negroes Were Never So Prosperous as Now”: Building Monuments of Protest

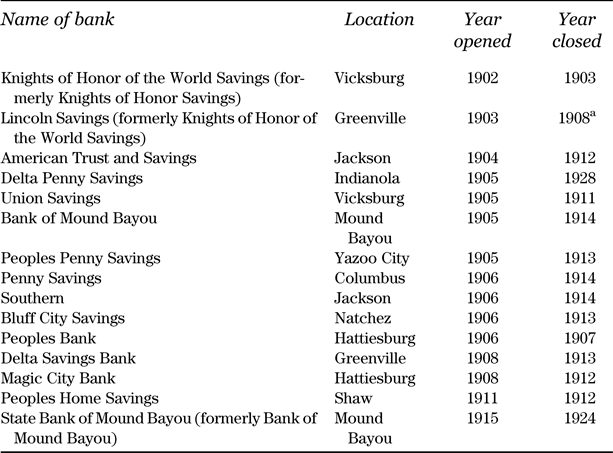

By 1910, in the few years after Lampton's bold pronouncement, Mississippi boasted an impressive eleven Black banks in operation (see Table 1). In cities and large towns, these banks often anchored thriving Black commercial districts, which included stores, restaurants, small businesses, professional practices, and entertainment venues that catered to an almost exclusively Black consumer base. In 1904, for example, a local Jackson paper took note of the Farish Street District, a Black enclave of over one hundred acres in the city, observing that “the negroes were never so prosperous as now and more of them are launching business concerns than ever before. . . . The established banking institutions are carrying more deposits made by negroes than ever before in the state's history and the assessment rolls show that they are entering all classes of business.”Footnote 11 These enclaves, even in smaller towns, drew thousands from rural hinterlands in search of services, shopping, and leisure, especially around annual harvest times and market days. Community institutions such as churches, schools, and secret societies, as well as predominately Black residential neighborhoods, helped shape these enclaves. Black banks also played a critical role in underwriting these “Black Wall Streets” and made bold appeals to race pride and self-reliance. American Trust and Savings Bank, the first Black bank in Jackson, boasted that it had “no white officers or depositors.” In its first three months of operation, it declared a dividend of 22 percent. “Not a white man has anything to do with this bank,” from the executives to the clerks to the teller cage, bragged the founders. Even the building was Black owned.Footnote 12

Table 1 Black-Owned Banks in Mississippi, 1902–1914

Sources: Howard University Commercial College, “Directory of Negro Banks,” in Commercial College Studies of Negroes in Business, vol. 1, Negro Banks (Washington, DC, 1914), 17–18; Charles Banks, Negro Banks of Mississippi (Cheyney, PA, 1909); W. E. B. Du Bois, “Table of Black Banks,” in Economic Co-operation among Negro Americans (Atlanta, 1907), 138.

a Merged with Delta Savings Bank of Greenville in 1908.

The number of Black banks in the state is especially impressive given that Mississippi helped author Jim Crow's primer. Immediately after the Civil War, Mississippi was the first state to institute Black Codes, statutes designed to return newly emancipated African Americans back to a state of quasi-slavery. Several Southern states immediately followed Mississippi's lead. In addition to prohibitions on interracial marriage, public assemblies, and owning weapons, the codes attacked Black economic autonomy. For example, the Mississippi code deputized any white person to arrest any Black person who left a white person's employ for any reason. In South Carolina, Black men and women had to obtain a special license to own a business or practice a trade outside of domestic service or farm labor. Some parishes in Louisiana required Black people to obtain the written permission of a white employer to sell goods and services on their own. These kinds of proscriptions tried to strike a blow against Black economic independence and to force enterprising Blacks under the power of local whites.Footnote 13

In the aftermath of the Civil War, Mississippi also strengthened its convict-leasing laws. Officials criminalized infractions as small as stealing a chicken or vagrancy, a catch-all status created to sweep large numbers of Black people into jails and prisons under dubious charges. Courts charged exorbitant fines for these small infractions, forcing largely impoverished Afro-Mississippians to labor under contract to white-only lessors who bid on the convicted persons. Reminiscent of slave auctions, lessors assumed and paid the court's fees. The convicted lessees then worked off the debt for terms that could last years. The state also leased thousands of prisoners to large planters, factories, mines, and timber companies. The arrangement benefited the state in several ways: “convict leasing would simultaneously provide workers to the state's labor-starved employers, earn revenue for depleted state coffers that could not otherwise afford to maintain the state prison, and provide a means of controlling the state's recently freed and largely impoverished Black majority.”Footnote 14 The first and second Mississippi Plans of 1875 and 1890 stripped Afro-Mississippians of political power: the first through violence, intimidation, and fraud and the second through constitutional provisions.Footnote 15

Economic repression extended beyond statutes. White Mississippians swiftly met almost any effort by Black farmers to organize for collective economic empowerment with repression. In 1889, for example, posses comprised largely of white merchants and planters killed at least twenty and as many as forty Black men, women, and children in Minter City to put down the Colored Farmers Alliance (CFA), which had negotiated relatively equal trade terms with a Farmers Alliance store in nearby Durant. In nearbyShell Mound, state militia and local whites murdered five suspected CFA leaders. For African Americans in particular, Mississippi earned its reputation as the “most Southern place on Earth.” An “American Congo.” A “dark journey.” These grim examples are merely a sample of countless instances of the repression African Americans faced, but they are also testaments of their persistence in spite of the consequences. Local CFAs and other groups like the Progressive Colored Farmers continued to sprout up despite the reality that participation could cost them their lives.Footnote 16

At the turn of the twentieth century, Afro-Mississippians continued to navigate a complex mix of quotidian and legal barriers to economic advancement. The most obvious trap, the crop lien, ensnared Black people in debt peonage. The scribbled entries in landlords’ and merchants’ ledgers caught Black men and women in an unending cycle of debt. In addition to marking up the prices of goods purchased on credit, landlords and merchants charged interest ranging from 30 to 110 percent at local stores. Smaller white farmers were not immune to such snares. They, too, banded together for mutual protection and interest. In some instances, however, white farmers’ leagues differed little from the Ku Klux Klan and other white militia groups. Groups such as the Farmers Protective Association and Farmers Progressive League met secretly; used oaths, passwords, and signs; and resorted to indiscriminate violence to reinforce their demands. The leagues drove Black farmers who owned their own land or rented land from Black landowners to work only on land owned by whites. The leagues extracted from merchants and bankers pledges that they would only furnish Black farmers who worked for white landlords. Black farmers who owned their own land had to seek the approval of local whites to keep their land or to borrow money to buy additional small parcels. Those Black men and women judged “safe and [who] knew their place” could get some concessions.Footnote 17 Even then, sellers inflated prices for Black buyers and restricted Black farmers to poorer-quality land. Buying, borrowing, and selling, then, are not purely economic exchanges in which race is epiphenomenal. Race is germane: whites used credit and lending to both replicate and reinscribe racial subordination.Footnote 18

Black banks helped Black farmers immensely by extending credit on fairer terms. By 1911, the fifty Black-owned banks in the United States—the overwhelming majority of them located in the South—had done an estimated $20 million in transactions for Black landowners. Workers, professionals, and business owners also relied on a network of Black-controlled banks, thrifts, mutual aid societies, and insurance companies to meet their financial needs. In addition to death benefits and loans for land and home purchases, societies also “provided a range of community services for education, health benefits, [and] funerals.”Footnote 19 Afro-Mississippians from across the state deposited money and invested in Black-controlled financial institutions, but they gained the fullest advantage of what one scholar describes as the “rainbow of economic dealings” in Black communities if a bank was located in or near their communities.Footnote 20 Black communities across the state seemed to catch bank fever; a few small rural towns even tried to organize banks. In 1904, Black residents in the small town of West Point tried and failed to organize a penny savings bank. The local newspaper praised the state attorney general for rejecting Black organizers’ “defective charter” and advised that “there is little need for negro banks in Mississippi, as there are enough banking institutions owned and controlled by white men.”Footnote 21

Black bankers sensed the magnitude of the role that Black banks played. In an address at the 1908 Mississippi Negro Bankers Association (MNBA) meeting, Rev. William R. Pettiford of Birmingham stressed, “No class of men in the civic walks of life ever had richer opportunities than those who are connected with the Negro banks. Not so much because of your chance to make money . . . but because of the great need of help among the people you are serving. . . . Your opportunities are rich because all classes of your people, the farmer, the business man and laborer[,] can be helped by you.”Footnote 22 Pettiford, however, minimized the obstacles Black bankers faced in fulfilling that role. They struggled against a steep learning curve. Some received assistance from local white bankers. Cashiers and other employees sometimes spent a few days with staff teaching them the basics of bank operations. John Strauther, founder of the Delta Savings Bank in Greenville, noted that local white bankers freely offered him and his staff advice and even loans. Early Black bankers also relied on bookkeeping and accounting correspondence courses and on industry books to learn the banking business. Charles Banks, founder of the Bank of Mound Bayou, owned an impressive library of books on banking and finance. Dr. William Attaway taught himself the insurance and banking business. Attaway served as the first president of Mississippi Beneficial Life Insurance and sat on the board of the Delta Penny Savings Bank in Indianola; later he cofounded the similarly named Delta Savings Bank in nearby Greenville. Contemporaries characterized Attaway as “the Negro Wizard of Insurance” and Banks as a “wizard of finance.”Footnote 23

Early Black bankers relied on each other as well. They leveraged their experiences from failed banks Black banks at new ones. For example, Taylor Genius Ewing Jr. had been head cashier of Lincoln Savings Bank before organizing the rival Union Savings Bank, also located in Vicksburg. Barred by custom from state and national banking professional associations, Black bankers forged their own networks. The MNBA, organized in 1905, and the National Negro Bankers Association (NNBA), organized a year later, provided limited but essential training in banking methods. Part professional association, part booster club, the MNBA met annually to share best practices and to promote the economic and social development of Black communities in the state. Topics at the meetings included advice about marketing, winning and keeping depositors, vetting loan endorsers, navigating panics, and collecting on past-due accounts.Footnote 24

The NNBA met annually in conjunction with the National Negro Business League. It organized roundtables on bank-related issues and connected established and would-be bankers to helpful resources and to each other. It had ambitious plans; it hoped to hire an accountant who would create quarterly reports about Black banking conditions and assist association members. NNBA president William R. Pettiford proved the association's most valuable and hardest-working apostle of Black banking. Pettiford traveled the country consulting with and training fledgling Black bankers. Pettiford, a Black banking pioneer, had founded the third Black-owned bank in the country: the Alabama Penny Savings Bank in Birmingham in 1890. He likely provided Minnie and Wayne Cox invaluable advice during the year they lived in exile in Birmingham after the Indianola Affair. Pettiford earned the nickname “‘Daddy’ of all the Negro banks in the U.S.”Footnote 25 He visited Mississippi at least once, speaking at the 1908 MNBA meeting in Mound Bayou.Footnote 26

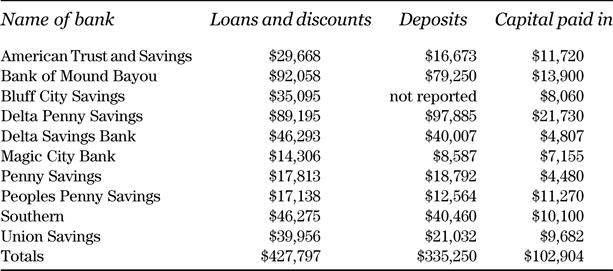

By the 1910s, Black banks in Mississippi had reason to feel like successful monuments of protest (see Table 2).Footnote 27 While their assets were impressive for a community struggling against racist exclusion and exploitation, those assets represented a fraction of the finance capital available in the state. For example, of the 332 state banks, Black banks combined held a mere 1 percent of the total loans and discounts in the state. This sobering statistic, however, does not capture the full impact of Black banks in their communities. In Jackson, for instance, more than five hundred Black men and women owned half a million dollars’ worth of real estate. American Trust and Savings Bank and Southern Bank, the two Black-owned banks in the city, held virtually all of the 566 mortgages, which they made on “easy terms” to Black customers.Footnote 28

Table 2 Assets and Capitalization of Black-Owned Banks in Mississippi, 1910

Source: Statements Showing the Condition of State and National Banks in Mississippi, 1910 (Nashville, 1910).

Note: “Loans and discounts” column includes loans, discounts on personal endorsements, real estate, or collateral securities.

The financial picture looked even rosier if one considered Black-controlled fraternal orders and insurance companies (see Figure 2). These financial institutions provided a range of financial services to Afro-Mississippians, including burial and death benefits, personal loans, and mortgages, and they invested in Black businesses, churches, and community groups. They kept part of their assets in Black banks, and they often shared with banks board members and stockholders. Fraternal orders and insurance companies counted among the active members and leadership of the MNBA and the Mississippi Negro Business League. For some sense of these societies as modest but significant economic powerhouses, in 1905 Mississippi boasted twenty-five Black-controlled societies with nearly 25,000 members and revenues of $400,000 (about $11.5 million in modern-day dollars), dwarfing the number of white fraternals. In 1908, at least four Black fraternals each managed more than a million dollars of insurance in force; not one of the five white-managed fraternals founded in the state could make such a claim. By 1910, the number of Black insurance societies stood at forty-six with over $27 million (about $761 million in modern-day dollars) of insurance in force. In 1910, the Mississippi Beneficial Life Insurance Company, an insurance company started by Wayne and Minnie Cox in 1908, became the first Black-owned company in the country to offer whole-life insurance benefits.Footnote 29

Figure 2. Office of the Excelsior Grand Court of Calanthe, ca. 1911, Edwards, Mississippi. The Calantheans were the women's auxiliary to the Colored Knights of Pythias. It operated a fraternal insurance program for women and children that rivaled that of its brother Knights. (Source: Isaiah W. Crawford and Patrick H. Thompson, eds., Multum in Parvo: An Authenticated History of Progressive Negroes [Jackson, MS, 1912]).

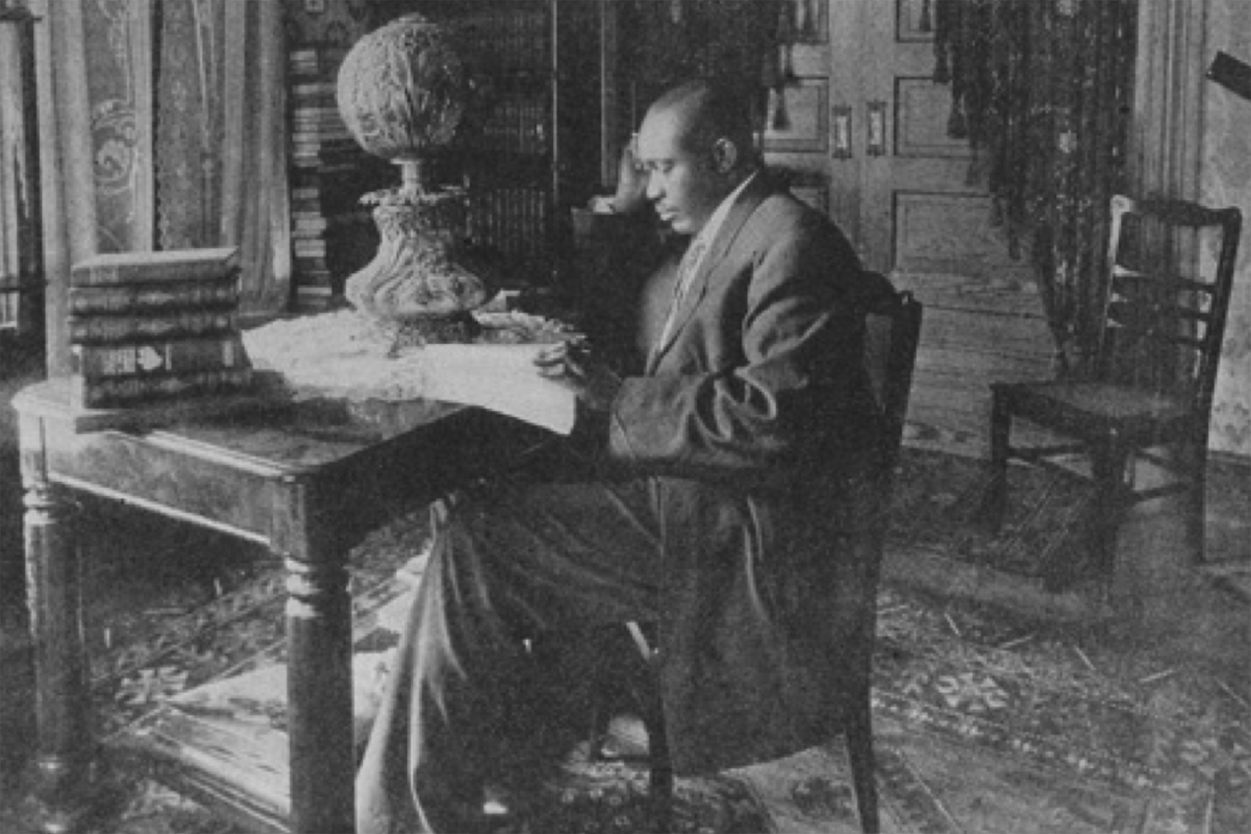

The modest but growing economic role of Black banks alone does not explain the tenacity with which white officials and citizens attacked Black banks. They perceived Black political power as a threat. Black Republicans influenced the national presidential elections, some local political races, and white appointments to federal patronage positions. For example, in the 1912 presidential election, Black men cast 4,000 of the 4,500 Republican votes in Mississippi. Ironically, the 1890 Mississippi constitution had effectively abolished the electoral power of the state's Black majority. Black Republicans represented only about 2 percent of eligible Black men of voting age, but voting as a bloc multiplied their power and could turn the tide in some contests. Thus, while the Indianola Affair had effectively diminished Black Republicans’ presence in patronage positions, their stature as a reliable voting bloc in the state gave them significant influence in assigning patronage to whites they deemed worthy—a state of affairs that sat uncomfortably not only with “lily-white” Republicans but also with Democrats. White Republican and Democratic interests, inside and outside of Mississippi, converged in a shared desire to stamp out Black political influence, particularly in the wake of the contentious 1912 presidential elections. Lily-white Republicans along with Democrats across the country launched baseless probes and planted unsubstantiated stories in the press about pervasive corruption and venality among Black Republicans. The national Republican Party passed resolutions to reduce Southern representation as an end run around Blacks’ political influence in the party (see Figure 3).Footnote 30

Figure 3. “But Heah I Is!,” political cartoon, 1916. A Black Republican bloc could wield influence on federal appointments for both white Republicans and Democrats. This state of affairs led to efforts to reduce Southern representation before the 1912 presidential election and during the 1916 elections. (Source: undated and untitled clipping from Tuskegee Institute News Clippings File, 1899–1966 [Sanford, NC, 1976], reel 4.)

The upcoming 1914 midterm elections only renewed whites’ unease about what they characterized as Blacks Republicans’ illegitimate and excessive political influence in the state. Some of the most vocal Black Republicans were also Black bankers or served on bank boards. Nearly all of the members of the delegation that visited President Howard Taft in 1909, for example, were connected to Black banks, including head cashier Charles Banks and president Isaiah Montgomery of the Bank of Mound Bayou; attorney Willis E. Mollison, president of Lincoln Savings; board member Dr. W. A. Attaway and president John W. Strauther of the Delta Savings Bank; T. J. Wilson, treasurer of the Grand Lodge of the Colored Masons; and president Wayne Cox and attorney and board member Perry W. Howard of the Delta Penny Savings Bank. Others, like Eugene and Mary Booze of Mound Bayou, earned reputations as well-known political bosses who controlled many of the plum patronage positions in their counties.Footnote 31

Some Afro-Mississippians possessed impressive wealth and social capital. For many of them, Black banks and fraternals had played crucial roles in amassing their fortunes. Dr. Sidney Redmond of Jackson, reputed to be “the wealthiest Negro in town,” owned over a hundred residential properties and two drugstores, most of which had been financed by American Trust and Savings Bank and other Black-owned banks in the state. Redmond served as president of American Trust.Footnote 32 A. J. Brown of Vicksburg owned a coal company and a brick manufactory with plants in Vicksburg and Kosciusko. He had sold more than 850 homes and farms to Blacks families between 1900 and 1908. Ephraim H. McKissack of Holly Springs headed the Colored Odd Fellows Benefit Association, which had more than one million dollars of insurance in force. McKissack also served on the boards of directors for both the American Trust and Savings Bank and Southern Bank, and he cofounded and served as general manager of the Union Guaranty Insurance Company. He owned property in Holly Springs and Jackson, Mississippi, and Memphis, Tennessee, making him one of the wealthiest men in Mississippi.Footnote 33

Though Black Republicans’ numbers were little threat to Democratic dominance, their political influence and growing economic power antagonized white legislators and citizens. More accurately, it was their performance of power that affronted the racial logic of Jim Crow in the minds of many white people: these Negroes with their White House delegations, filibusters at Republican committee meetings, and letters back and forth with federal officials magistrating yeas or nays about which white folks were right for local offices. The smell of sawdust from newly constructed halls and houses, the gleam from a Black child's new pair of shoes, and the conviction with which a sharecropper slapped crisp dollar bills on the general store counter reeked of the taint of dreaded Negro rule. Ridding the body politic of this cancer demanded skillful precision rather than indiscriminate brawn. Legislators easily justified to themselves the urgent need to remove what they saw as the corrupting influence of Negro venality and profiteering in public life, spread by Black banks and their bankers.

Black banks were a particularly effective target. The practical effect of banking regulation reached deep into the communal and economic networks of Black financial institutions and communities. Black banks housed the funds of other financial engines in the Black community: churches, secret societies, and insurance companies. For example, the Knights and Ladies of Honor deposited the lion's share of its revenues in the Knights of Honor Bank and, later, Lincoln Savings. The Masonic Benefit Association (MBA) boasted over $1 million of insurance in force (equivalent to $26 million in modern-day dollars) by the 1910s. The MBA deposited part of its revenues in the Bank of Mound Bayou, as did the Sons and Daughters of Tabor, which also operated its headquarters out of the Bank of Mound Bayou building. The Union Guaranty Insurance Company depended on the Southern Bank in Jackson. Both the Woodmen of the Union Benefit Association and the Mississippi Life Insurance Company relied on the Delta Penny Savings Bank in Indianola. These financial institutions also employed hundreds of Black men and women. The Black men and women who occupied these middle-class, white-collar jobs escaped the typical low-paying, servile, grueling, and often dangerous jobs left open to Black people as domestics, agricultural laborers, and factory and mill workers. For Black women, in particular, Black financial institutions provided white-collar jobs that allowed them to escape the sexual harassment and violence they often faced working in whites’ homes. Black banks in Mississippi blazed trails for women as well: two banks, Lincoln Savings and American Trust, had women head cashiers.Footnote 34

Black banks were also sources of easy credit and financial assistance for Black businesses. For example, Mississippi Life and the Delta Penny creatively managed their financial relationships. Before stricter regulation prevented such collusion, the Delta Penny required that anyone receiving a loan from the bank take out a Mississippi Life policy in the principal amount of the loan and designate the bank as sole beneficiary. Other Black banks engaged in even more questionable financial practices. Delta Savings Bank in Greenville had gone nearly bankrupt in 1912 but local lore holds that it survived because local Black prostitutes persuaded their white clients to deposit money in the bank. The bank still failed in 1913.Footnote 35

Perhaps most alarming to the white business-civic elite was the threat that Black banks posed to the crop-lien and sharecropping systems, the most prevalent and abusive forms of credit for farmers who owned little or no land. Black farmers without land of their own exchanged their labor to large landholders for a portion of the crop. Landlords charged for everything, locking tenants and sharecroppers in a never-ending cycle of debt. Independent Black farmers, too, desperately needed access to loans and credit to keep their farms afloat. The most common financing options available to early twentieth-century farmers included banks, cotton factors, larger landowners, and supply merchants or local storekeepers. It is not likely that Black cotton farmers could take advantage of creative financing options such as local farmers unions and cooperative groups’ warehouse certificates utilized by white farmers. Black farmers, even more than working-class mechanics and labors, invested heavily in Black banks and served on their executive boards, as anxious perhaps to lock down ready sources of funding as to boost the reputation of the banks. The Peoples Penny Savings Bank in Yazoo City, for example, advertised that some of the most prosperous Black landholders in the state held stock in its bank. Bryan G. Vernon of Vicksburg, one of the largest Black farmers in the county, was a major stockholder in the Union Savings Bank in Vicksburg.Footnote 36

Black banks typically offered credit and loans to farmers at rates considerably lower, and at terms more aggregable, than white planters, merchants, and bankers. Loans and credit from Black banks enabled sharecroppers and farmers to purchase desperately needed supplies and to take care of family needs and expenses. Doing business with Black banks left open the very real possibility that farmers could make a profit at the end of the picking season and have cash money left in their pockets. The threat that Black farmers could move from under the thumb of debt peonage metastasized the cancer of Black political influence in the minds of whites across political allegiance and social class. Reform would prove a highly effective tool for checking Black ambition. Through banking regulation, particularly for Black banks, legislators could proverbially kill multiple monuments of protest with one regulatory stone.

The Devil This Side of Hades: The Mississippi Banking Law of 1914

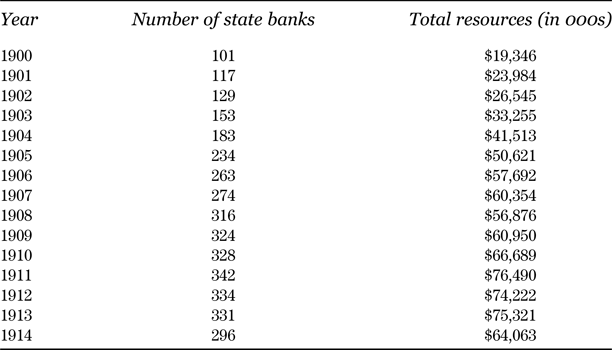

By the time the state legislature convened in January 1913, few could plausibly deny the need to strengthen the state's oversight of its banks.Footnote 37 The Panic of 1907 had lain bare serious defects in the state's banking industry. Between 1907 and 1914, at least one hundred banks failed every year, with 1911 to 1913 representing some of the worst years. The number of bank start-ups, however, proved robust enough to show a net increase in the state's numbers of banks. Depositors complained to and sought relief from their state representatives, and the state legislature did take some halfhearted steps toward addressing the problem of bank closures. In his inaugural address during the 1912 session, Governor Earl Brewer acknowledged the importance of banks to everyday citizens and the lack of protection for consumers. In 1913, the House and Senate made a resolution to study banking conditions in the state and make recommendations to the 1914 session. Apparently, legislators did not take the problem seriously enough to suggest new laws, perhaps because enough banks had either opened or reopened to realize positive growth, however anemic, in the numbers of state banks every year (see Table 3).Footnote 38

Table 3 Number of Mississippi State Banks and Total Resources, 1900–1914

Source: Superintendent of Banks, State of Mississippi, Statements Showing the Condition of State and National Banks in the State of Mississippi, 1932 (Jackson, MS, 1932), 87110, reprinted in George S. Peck, “A Critical Survey of State Commercial Banking in Mississippi” (PhD diss., Indiana University, 1952), 29.

The highly publicized late-1913 failure of the First National Bank in Natchez, which resulted in losses of more than half a million dollars (about $13 million in modern dollars), made it impossible for legislators to ignore the state's banking crisis. The bank's failure had a ripple effect on other banks across the state. As the legislature sat in session during the first two months of 1914, more banks continued to fail. Wanting to show itself proactive on the issue of banking reform and to deflect mounting criticism, the legislature significantly appended the state's banking laws. The 1914 law established a governor-appointed Board of Examiners, with commissioners to serve four-year terms. The commissioners supervised a team of examiners who inspected banks in the state twice a year; the surprise audit represented a key tool in the examiners’ arsenal. Not surprisingly, the specter of an examiner appearing at a bank's doorsteps to conduct an in-depth audit without prior warning irked a number of bankers.Footnote 39

The new guaranty of deposits provision, however, drew the most vocal and harshest criticism. The guaranty provision represented a type of insurance protection for customers’ deposits. The proposed plan required banks to pay a percentage of their deposit balances into a centralized fund. In the event any bank in the state failed, the fund would supplement whatever money a receiver was able to recoup for bank customers. While deposit insurance would become a hallmark of New Deal legislation in the 1930s, several northeastern and midwestern state legislatures first developed deposit guaranty funds, early versions of deposit insurance, in the early nineteenth century. States’ interest in guaranty funds waned, however, following the emergence of a national banking system and the increased use of national bank notes beginning in the 1860s. The rapid growth of deposit banking in the late nineteenth century revealed the need to provide stronger protections for depositors, but states were reluctant to readopt the older guaranty fund models. Starting in the late 1880s, nearly two dozen state legislatures proposed potential statutes establishing guaranty funds, but none passed.

The Panic of 1907 thrust to the forefront of national attention questions about the state's responsibility to assume a greater role in protecting bank customers. William Jennings Bryan included a deposit guaranty program as part of the platform of his unsuccessful 1908 presidential campaign. Nearly half a dozen states took up the question of a state-managed guaranty system in the wake of the panic. Early versions of the 1913 bill that would eventually become the Federal Reserve Act had included a deposit guaranty provision, but it did not make it into the final version of the bill that passed in December 1913. By World War I, eight states had adopted deposit guaranty provisions. The fact that eight states passed guaranty provisions acknowledged not only growing public interest in adopting more aggressive bank reform measures but also the growing importance of local banks in the economic and social lives of everyday citizens. At the same time, the low numbers of state guaranty programs, as well as failures to enact guaranty provisions at the federal level, reflected the complex political and cultural dynamics that influenced the political will to confront questions of state responsibility to protect consumers.Footnote 40

Some Mississippi bankers were apoplectic with rage when news of the proposed deposit guaranty provisions in the new banking law leaked to the public in early 1914. A bit of their angst may have been leftover resentment over passage of the Federal Reserve Act a few months earlier. The Democratic Party, controlled largely by Southern states, fought the bill vigorously, claiming, among other criticisms, that a central bank represented an invidious, monopolistic “money trust.” More Representatives from Mississippi than any other state participated in debates about the bill in the U.S. House. Carter Glass, Representative from Virginia and chairman of the Banking and Currency Committee, further revised the reserve-system bill and eventually won Democrats’ support in the House and Senate, though back in Mississippi a vocal group of bankers carped about the new reserve system.Footnote 41

Leaders of the Mississippi Bankers Association (MsBA) called on all bankers in the state to “wage an open and aggressive lobby against the guarantee clause” in the state's new banking bill.Footnote 42 They believed the guaranty requirement infringed on bankers’ autonomy. Mississippi state senator Jesse Denson, who was a member of the banking committee that helped draft the new law, even criticized the state's new banking law as “wrong in principle and vicious in effect.”Footnote 43 Criticism in the state House was particularly “contentious,” a local paper reported—not surprising, the journalist surmised, since a sizable number of representatives were also bankers. Enough “ugly words” flew around during two days of debates that the House vote had to be postponed until tempers cooled.Footnote 44

Other critics framed their concerns in terms of privilege and character. They protested that the new provisions encouraged inexperienced or speculative newcomers to enter the field. It made lax bankers more imprudent because the act offered an out when—not if—their banks failed. Charges of socialist leanings and radical subversion peppered bankers’ criticisms as well. Some state banks threatened to become national banks rather than comply with the guaranty provision. As a concession to widespread resistance, the Mississippi Senate added a proviso allowing banks a year, until March 15, 1915, to comply with the new guaranty provisions. The bank examinations and other provisions of the law, however, took effect immediately.Footnote 45

Though not singled out in legislators’ jeremiads about federal intrusion, autonomy, and character, race suffused the subtext of the state's new banking law. In his welcome address to the MsBA meeting in the summer of 1914, former mayor of Vicksburg and bank president B. W. Griffith reminded bankers that Mississippi had “purer Anglo Saxon blood than that of any state in the Union.” He also invoked the Civil War as a crucible from which the state had emerged stronger.Footnote 46 Indeed, MsBA president J. F. Flournoy echoed Griffith by comparing passage of new federal banking laws to Civil War conditions, a time when the federal government exercised “vast power” over the South.Footnote 47 Local priorities, political differences, and questions of economic diversification and personal qualifications often divided MsBA members. Invocation of racial purity and the “Southern way of life”—undergirded by imagined racial hierarchies—rallied the disparate factions within the organization.Footnote 48

The new 1914 law reflected the wave of progressive, state-level reforms of business and public institutions sweeping the country. In theory, regulation made capital socially responsible and compelled the state to protect legitimate social institutions to ensure that they served the people. In practice, however, notions of who was responsible to whom, what institutions were legitimate, or even who were “the people” meant that certain constituencies and institutions received protections while the state targeted others for exceptional censure. Nested within the silcrows and the arcane, antiseptic legalese of the statute lay emotional assertions of whiteness and manhood. Mississippi reformers narrowly defined legitimate participation in the political economy to exclude African Americans. White supremacy informed notions of manhood and mastery in ways that cut across class, consistently undermining solidarity around issues of economic and political rights that the poor, working, and middle classes shared across racial lines. Instead, racial hierarchies invested whiteness with a social, cultural, and political currency that undergirded whites’ claims to citizenship and access while marking those same rights as off limits to African Americans. Afro-Mississippians’ economic autonomy and civic involvement threatened fundamentally the claims of whiteness to political power, economic independence, and social identity and thus set Afro-Mississippians squarely in reformers’ crosshairs.Footnote 49

Clearly, the 1914 Mississippi Banking Law was not created specifically to dismantle African American banks, but one should not ignore how so-called colorblind regulations alternately mask and exacerbate inequities around not only race but also gender. The debates over the Federal Reserve and the banking law reinforced the critical links between political economic power and manly independence. White men conscripted state power to legitimate the new banking law in multivalent ways. They projected their power and asserted their influence by policing symbols of Black economic autonomy, respectability, and political influence. The examinations afforded them closer scrutiny of and greater leverage over Black banks, customers, and assets. To be sure, both white- and Black-controlled banks needed reform and regulation, but bringing down a strong regulatory arm on Black banks in particular reinforced both the efficacy of stronger banking reform and Black people's lack of capacity to engage in the highest echelons of American business.Footnote 50

Whites certainly did not need a statute to shut down Black banks. The experiences of Peoples Penny Savings Bank in Yazoo City and Bluff City Bank in Natchez portend the willingness of whites to use state police powers to close Black banks—with or without a law. In May 1913, Peoples Penny president Rev. Henry Howe King and cashier Albert Banks faced seventeen counts of fraud and criminal misconduct. Cashier Banks, a former president of the Mississippi Negro Business League, also faced criminal theft charges. Local authorities claimed King and Banks took money from depositors and stockholders although the two men knew Peoples Penny was practically insolvent.

When the bank opened in 1905, its future had looked very promising. John L. Webb, leader of the Colored Woodmen, had been a driving force behind the bank's founding. Peoples Penny held some of the Colored Woodmen's assets. As one of the most successful Black-controlled fraternal insurance societies in the region, the Colored Woodmen's assets buoyed the bank's financial growth in its early years. By 1911, investors had paid in all of Peoples Penny's $10,000 capital, and the bank maintained a modest reserve.Footnote 51 However, the bank's liberal lending practices spelled trouble: It had $38,000 in outstanding loans but less than $2,000 cash on hand and $15,000 in time certificates of deposit, which are similar to modern-day certificates of deposit, or CDs. The bank operated much like a pawn shop. Customers used guns as collateral for short-term loans. On the surface, such credit terms seemed suspect. On closer consideration, however, Peoples Penny's credit terms responded to the community's credit needs and practical realities. Sharecroppers and small farmers, who were often in desperate need of cash and credit, owned precious little collateral. While a vault full of guns represented the valuable assets of small rural farmers, they were not fungible assets for bankers. A slew of defaulted loans coupled with Peoples Penny cashier Albert Banks's alleged thefts from the already small deposit accounts severely impaired the bank. By 1913, it must have been practically defunct on paper, but bank president King may have either been unaware of the bank's serious financial impairment or believed that increasing deposits could save the bank.Footnote 52

Local white authorities used the local criminal courts instead of leveraging the state's existing banking regulations to wrest control of the bank. When white Yazoo City citizens arrested, charged, and tried King and Banks, they also seized control of the bank, its assets, and its portfolio of loans. The sensational local headlines about the trial communicated different messages to white and Black communities. To whites, the headlines conveyed the criminal and, therefore, dangerous ineptitude of Negroes who dared fancy themselves financiers. To Afro-Mississippians, the headlines served as reminders of the far-reaching power that whites could and would exercise over their financial lives.Footnote 53

Bluff City Savings Bank in Natchez provides another example of how state powers could crush even successful Black banks. “The leading colored citizens” of Natchez, proclaimed local newspapers, had chartered Bluff City Savings in late 1905.Footnote 54 The bank quickly sold its outstanding stock and maintained a conservative loan portfolio. Bluff City became an important source of small, short-term loans. Farmers, for example, could get $40 or $50 using their mule, livestock, and farm equipment as collateral. The bank also made larger loans, such as mortgages on homes, farms, and churches.Footnote 55

Two unfortunate circumstances in late 1913 caused the bank to falter. First, in late October First Natchez Bank failed, which had a ripple effect on other banks in the area. The First Natchez closure led to a run on all banks in and around Natchez. Second, Bluff City directors decided to close the bank temporarily as a precautionary move. Bank president Samuel H. C. Owen stressed publicly the directors’ decision to give the bank time “to meet at once the demand[s] of all depositors.”Footnote 56 However, the temporary closure proved permanent.Footnote 57

During the hiatus, a bonded receiver or perhaps members of the bank's board discovered about $1,500 in missing funds. Police charged assistant cashier Major Davis with embezzlement and arrested him in January 2014. Black banks were not immune to embezzlement or even outright theft at the end of a gun; in most instances, however, thefts and even embezzlement on their own were not enough to fell a bank. If Davis had embezzled funds, his act violated the community's trust. Working-class men made up nearly two-thirds of Bluff City Savings’ stockholders, and they likely made up most of its depositors. It was as if Davis had reached his hands not only into the bank's tills but into workers’ very pockets. While sobering, the closure in October and Davis's subsequent arrest did not signal a death knell for the bank. It had $50,000 in assets and, unlike many small Mississippi banks, white or Black run, its outstanding loans represented a conservative portion rather than a lion's share of its ledger.

When the bank did not reopen after a couple of months, Natchez's Black community demanded reassurances. More than seven hundred depositors met at the local Colored Knights of Pythias Hall in late January to consider their options. Natchez's white business-civic elite, however, quickly dashed any hopes that the bank would reopen. The local court ordered that the bank be placed in receivership. Mississippi newspaper headlines detailing Davis's trial, eventual conviction, and sentence of five years in Parchman prison fed Mississippians’ bile aboutagainst bank closures and reaffirmed the wisdom of the state legislature in creating new legislation to protect bank depositors.Footnote 58

But Bluff City Savings was nowhere near insolvent. It was in remarkable financial health, even considering the October bank run. Surprisingly—or perhaps not—white Natchez residents pressed city authorities to keep the bank closed and to force liquidation of its assets. They demanded the bank immediately call due and payable its loans and mortgages, whether the borrowers were in default or not. Within three years, the court-appointed receiver recovered nearly two-thirds of the amounts that depositors “lost” when the bank closed—both a testament to the bank's conservative lending practices and a furtive nod to the easy terms that allowed locals to buy up Bluff City notes and properties for pennies on the dollar. For example, one buyer snapped up more than $750 in notes for $53 at auction.Footnote 59

A Negro “Who Knows How to Handle the Typical Southern White Man”: Black Banks Confront the Mississippi Banking Law

The newly minted bank examiners fanned out across the state beginning in March 1914. Of the peak number of twelve Black banks in 1910, only a third remained open by early 1914 (listed by date of opening): Delta Penny Savings in Indianola; Bank of Mound Bayou in Mound Bayou; Penny Savings Bank in Columbus; and Southern Bank in Jackson. None of the surviving Black banks was expected to escape the examiners’ scythe. It was not that Black banks did not need any regulatory oversight or correction; like virtually every bank in the state, decades of operating with little oversight had resulted in some financially suspect practices. Institutional and structural barriers related to racial discrimination, however, compounded the problems of Black banks. Limited access to formal and informal banking education—especially mentorship by experienced bankers through apprenticeship and networking in professional banking associations—made it more, not less, likely that Black banks would fall short of industry best practices. Black banks also relied on an overwhelmingly Black customer base, namely farmers, professionals, business owners, and workers, who were economically vulnerable—partly because of the vicissitudes of the market but mostly because of extralegal and state-sanctioned economic exploitation and violence.

Black banks faced a peculiar paradox: Those banks beset with problems reinforced in many white Mississippians’ minds the worst of the Negro that they had come to expect. Those banks able to overcome the myriad problems facing them and to manage some modest success increased the likelihood that they would become targets of intimidation and whitecapping. Black bankers, then, had reason to feel especially targeted by the new legislation given examiners’ vigorous and enthusiastic scrutiny. These sites of power became even more vulnerable to attack.Footnote 60

Newly minted bank examiner James Sanford Love was laser-focused on eliminating Black banks. Love did not come from remarkable circumstances. Born in Noxubee County in 1877, he was one of seven children. He learned something about handling money and credit working in his family's store in Brooksville. Though the store belonging to his father Davis Love saw only a fraction of the success of W. H. Scales, who owned a chain of stores throughout central Mississippi including one in Brooksville, Love learned crucial lessons about local finance. Rural merchants served important financial roles, both as providers of goods along vital railroad lines and as intermediaries between cotton farmers and more formal financial markets, acting at various times as brokers, salespeople, investors, and even town builders.

Love attended Mississippi College for a few years before taking a bookkeeper job in a small-town general store. He had learned, through his father's example and with a weather eye on Mississippi's modernizing political economy, that the general store was in many ways fading as the central financial hub of local economies. He saw in his father his own future if he stayed at the store. By the late 1890s, Davis Love had lost his store and made his living selling hats door to door. James Love saw a more promising future in banking. In three years, he advanced from the counting room of a small-town bank to a general bookkeeper position at a large national bank in Hattiesburg. In 1900, with money saved and connections made, an ambitious Love cofounded the First National Bank in nearby Lumberton, where he served as vice president and head cashier. Through a combination of luck, profitable connections, and successful investments, the bank prospered. Love launched into other businesses and earned a reputation as one of the ablest young financiers in the state. In April 1914, after earning top marks on the certification exam, he became chairman of the Board of Examiners and the bank examiner for the Second District of Mississippi.Footnote 61

The most experienced in banking of the three new examiners, Love attacked his new position with relish. He launched an all-out assault on the remaining Black banks within his district and beyond, and he had the tacit if not explicit consent of some members of the banking community. Mississippi bankers did not hide their racist attitudes. During annual MsBA meetings, jokes about ignorant aunties, Sambos, and pickaninnies peppered formal speeches and remarks before the hundreds of delegates and visitors assembled. Underneath that contempt lay real anxiety about whites’ utter dependence on Black labor. In 1914 Oklahoma banker W. B. Harrison addressed the MsBA meeting in Vicksburg. He advocated food crops, cattle ranching—any agricultural pursuit to replace cotton: “Nothing but cotton means a ten dollar mule hitched with rope traces to a two dollar plow, dragging behind it a black man lazier than the mule . . . whose highest ambition is to raise enough pickaninnies . . . so he will not have any cotton picking to do himself.”Footnote 62 Harrison stressed the need for dramatic changes in the state's economy as a way to rid Mississippi of the Negro—and of white men's dependence on Black labor.

Examiner Love encouraged the other examiners to do everything within their bureaucratic power—and social influence—to ensure the Black-owned banks did not pass the new state-mandated audits. Penny Savings Bank in Columbus certainly felt the regulatory heat. Wayne Cox had helped organize the bank in 1906 and served on its board. Bank examiner Samuel Story Harris's first mid-1914 report of the bank's assets and liabilities revealed no serious flags. After his second surprise audit less than two months later, however, Harris suddenly was less sanguine about the bank's prospects. A series of foreclosures and courthouse-steps sales advertised in the local paper offers some sense of the bank's efforts to meet Harris's demands. Similar to the receiver assigned to Bluff City Savings in Natchez, Harris may have demanded that the bank liquidate or call due and payable immediately some of the bank's investments, namely the Black farms and homesteads on which the bank held mortgages.

The borrowers may or may not have been making timely payments, but it would have been virtually impossible for small farmers and difficult for even the wealthiest farmers to pay off loans in advance of harvest season—and even more difficult given falling cotton prices over the previous few years because of the boll weevil infestation that ravaged the state only one year after the 1907 panic. Black business owners and professionals would have been affected, because they too depended on locals’ flush times after harvest to pay outstanding bills and purchase goods and services. The case of Penny Savings bank customer King Smith offers a sense of the long-term detriment of Penny Savings’ liquidation. Smith not only lost the small farm he worked with his wife and young son James in an auction on the courthouse steps; he also lost his two cows, Spot and Sue, two mules, and a horse wagon. For farmers like Smith who could not meet the tight deadlines set by the examiner, their farms represented the bulk of their wealth and the foundation of their security. With no Black banks standing, it would be difficult for King and others to secure another farm without entering into a patronage relationship, often to the Black farmers’ detriment, with white planters. Examiner Harris liquidated the Penny Savings on October 10, 1914.Footnote 63

Southern Bank in Jackson survived its sister bank American Trust and Savings Bank, which folded in 1912. Louis K. Atwood, attorney and fraternal leader, resigned from American Trust to found Southern in 1906. The bank looked strong on paper: It had over $46,000 in deposits and had increased its capital requirement to $30,000. After a thorough review, examiner Edgar Anderson admitted that he found “nothing in the way of irregularities” but still felt it “advisable to close the institution.”Footnote 64 It seemed factors beyond the bank's ledger books held sway. Atwood had been outspoken in his support for the Republican Party as editor of the Jacobs Watchman. The fraternal society Atwood headed, the Order of Jacobs, housed part of its considerable assets in the bank. In 1910, Atwood organized the Union Guaranty Insurance Company, and it too held some of its assets in the Southern. Local whites also undoubtedly knew that Calvin Miller of Rolling Fork, a Black man lauded as “the biggest farmer in the Delta,” held deposits in the bank.Footnote 65 Atwood, Miller, and other bank officers “sacrificed their personal property” to ensure that depositors were paid in full when the state closed the bank. Two local white banks took over American Trust's business.Footnote 66

The two remaining Black banks fell within James S. Love's district: the Bank of Mound Bayou in Mound Bayou and Minnie and Wayne Cox's personal monument of protest, the Delta Penny Savings Bank in Indianola. In late August 1914, Love dispatched assistant examiners to the Bank of Mound Bayou in cashier Charles Banks's absence (see Figure 4). Banks was four-hundred miles away in Muskogee, Oklahoma, attending the fifteenth annual convention of the National Negro Business League. He presided over the Negro Bankers Symposium on August 19, held on the first day of the three-day meeting. That same day, Love ordered the bank closed. Before Banks could return home, Love ordered the bank's assets liquidated on August 21.

Figure 4. In addition to communicating Charles Banks's wealth and refinement, his impressive library reveals his voracious appetite for learning, especially about business and finance. (Source: “Private Library of a Prosperous Home,” in Progress and Achievements of the Colored People, by Kelly Miller and Joseph R. Gay [Washington, DC, 1917], New York Public Library Digital Collections, https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47de-4d06-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99.)

The Bank of Mound Bayou represented a particularly coveted notch in the regulators’ belt. Mound Bayou, an all-Black town founded in 1887, enjoyed accolades around the country as an example of what Black self-determination could achieve under one of the most repressive Jim Crow systems in the country. Prosperous farms and businesses dotted Mound Bayou, including drugstores, restaurants, real estate companies, professional offices, and a rare jewelry repair business. The town had its own post office and railroad station, and it boasted small industries and utilities, including two gins, two sawmills, an ice plant, a brick factory, a telephone exchange, and an electric power plant. Booker T. Washington raised the town's national profile by funneling investment capital from the likes of Andrew Carnegie and Julius Rosenthal to the small town. Charles Banks dealt intimately with these titans and other investors to achieve his dream of making Mound Bayou the center of Black-controlled industry in the country. The Mound Bayou Oil Mill and Manufacturing Company opened in 1912, and it joined other small industries in the town. The oil mill failed in a few short years, but for many it represented the possibilities of Black industry in the South.Footnote 67

Charles Banks, the cofounder and head cashier of the Bank of Mound Bayou, had spent much of his professional life extolling the possibilities of collective racial uplift through entrepreneurial development, self-help, and interracial cooperation. Banks included civic and political leadership in his calculus. An ambitious town like Mound Bayou, which Banks hoped would eventually “own and control all [of] the land that can be brought under our influence, and connect [it] to this [30,000 acres] which we already have,” needed political influence to ensure its growth and protection.Footnote 68 Banks remained active in the Republican Party at the state and national levels, and he cultivated relationships with members of the white business-civic elite in Bolivar County and throughout the Mississippi Delta. Publicly, Banks palliated whites’ jealousies and manipulated their sentiments through fawning compliments and an active private correspondence. On various occasions, Banks publicly credited whites for Negroes’ success. For example, in a widely circulated letter announcing the opening of the Mound Bayou Oil Mill, he proclaimed, “What we have done here [in Mound Bayou] is as much a compliment to the white man[,] under whose supervision and direction we are, as it is to the negro.”Footnote 69 Banks intentionally used a lowercase “n” in Negro; he confided in personal letters that he used such tactics “to strip [the white man] of any fear or suspicions of what such progress means to him.”Footnote 70 His efforts proved inadequate against the machinations of whites determined to undermine the growing economic and political influence of men like Banks and the last-standing Black banks in Mississippi.Footnote 71

Love's stealth audit of the Bank of Mound Bayou in Banks's absence was no accident. He likely calculated that the bank's employees were not as intimately familiar with the bank's records, nor could they wield the same influence as Banks with local whites to intercede on the bank's behalf. Love may also have wanted to avoid a direct confrontation with Banks, who, though self-taught, wielded a formidable knowledge of banking and finance. Love probably knew that he would not find any operating issues serious enough to shut down the bank and so denounced the character of the securities representing the bank's primary investments. When the receiver S. D. McNair, after reviewing the Bank of Mound Bayou's books, questioned why such a well-run bank had been placed in receivership, Love told McNair that “the securities were Negro securities, representing Negro industry and Negro enterprises and for the most part covering the progress of the Negro town.” If he called the securities due and payable, “they would be covered by Negro money.” Thus, in Love's opinion, “and according to his rule,” Negro securities “were not worthwhile.”Footnote 72 Love's comments reveal how the tools and technologies of finance, such as bills of exchange, stock certificates, and even extended forms of credit, can be tied to racial exploitation: these tools both mask and extend racial exclusion. What counts as capital shapes and is shaped by understandings of race. Having seen the bank's securities firsthand, Love understood that shutting down the bank would have a disastrous effect on Black economic progress extending far beyond the bank's four walls. Black newspapers were vocal about the role racism played in the bank's closure. A headline on the front page of the Topeka, Kansas, Plaindealer, for example, proclaimed, “Race prejudice kills popular Negro institution.”Footnote 73

As with the other Black banks, the Bank of Mound Bayou's closure did indeed have a domino effect on other Black-controlled financial institutions and businesses. A week after Love ordered the bank closed, the Masonic Benefit Association went into receivership. The MBA was the largest insurer of Afro-Mississippians in the state; it paid claims upwards of $300,000 (nearly $8 million in modern dollars) each year. When Love closed the Bank of Mound Bayou, the modern-day equivalent of more than $2 million in claims were left unpaid. The MBA, first organized in 1880, went out of business in September 1914.Footnote 74

With the closure of the Bank of Mound Bayou, only one bank remained: the original “monument of protest” that had helped fuel the dynamic growth of Black banks in the state. Wayne and Minnie Cox's Delta Penny Savings Bank in Indianola easily passed its first round of audits in June 1914. Its founders enjoyed significant stature in the region. Aside from Minnie Cox's national profile because of the Indianola Affair, Wayne Cox had garnered a reputation as a political boss with some influence in the Delta. He helped funnel plum patronage positions to local whites. A white contemporary described him as a Negro “who knows how to handle the typical Southern white man.”Footnote 75

The bank's importance to Afro-Mississippians and whites in the Mississippi Delta, too, cannot be overstated. It was centrally located in the Delta, one of the most economically important regions in the state, and made loans both to white and Black planters farmers. It held hundreds of mortgages for Black farmers and helped area Black businesses with lines of credit and short-term loans. In 1914, it had over $155,000 in assets (about $4 million in modern-day figures). The assistant examiner noted that the Delta Penny had a “good reputation” throughout the state, and his examination bore out that assessment.Footnote 76 Examiner Love, however, was not satisfied. Love told Wayne Cox, “I do not think that I will qualify your bank under any circumstances”—words he meant as both a promise and a threat.Footnote 77 Over the next six months, between June and December, he had examiners return at least six more times to audit the bank.Footnote 78

In January 1915, Love's assistant recommended that the state issue the Delta Penny a guaranty league certificate, meaning that it could guarantee deposits. Love had made no secret to others that he believed “the Guarantee [sic] System was too good for Negroes” and that no Negro bank would, if he could help it, receive a certificate under any circumstances.Footnote 79 Despite his best bureaucratic efforts, the Delta Penny not only remained open but continued to prosper. The bank's portfolio included some loans to whites, and the Coxes owned considerable property throughout Sunflower County and other parts of the state. Love announced that he needed to make a thorough examination in person.

It would not be so easy to dismantle the Coxes’ small empire, but Love would try. He blustered into Indianola in April 1915, and his publicized arrival had precisely the effect he had calculated. Worried depositors made a run on the Delta Penny, which tested its reserve funds. However, the bank's largest depositors, which included the Coxes, kept their considerable assets in the bank, which likely helped it survive the run.Footnote 80 The bank still stood after the run, but it was in a financially compromised state. Love smelled blood in the water and made a number of unreasonable demands. For example, he demanded that the bank retire nearly half (40 percent) of its bills payable. The bank made virtually all of its non-mortgage loans to farmers, who would not have the cash to pay part or all of their accounts until after harvest season; even then they would have considerably lower funds available because of depressed cotton yields and prices, which had dipped as low as ten cents a pound, resulting from the boll weevil scourge and a recent flood. To the surprise of most observers, the bank's board met the requirement.Footnote 81

Running out of schemes to shut down the bank, Love calculated that he could leverage any vestiges of local white resentment—or, at the very least, white self-interest—for help to close the bank. Love told Wayne Cox that the Delta Penny Savings would have to get two endorsements totaling $20,000 (over $500,000 in modern-day dollars) from the two white banks in Indianola. He gave Cox three days to secure them and returned to Jackson to await what he presumed would be the Coxes's inevitable failure. After more than a week, Wayne Cox entreated Love to come back to Indianola to discuss the endorsement requirement. Love could not resist the chance to witness firsthand the bank's failure. After Love arrived on May 20, a penitent Cox begged if there was anything else the bank could do beyond securing the $20,000. Love, confident of his victory, told Cox this requirement was the last and if the bank could not meet it, he would close its doors that day. To Love's amazement, Cox produced the pledges for $20,000 from both the Indianola State Bank and the Sunflower Bank of Indianola.Footnote 82 Having publicly announced that he would add nothing else, Love reluctantly approved the Delta Penny Savings Bank. It became the only Black-owned bank in Mississippi licensed to guarantee deposits—and the last Black bank left standing in the state.Footnote 83

In the light of the present day, it is hard to assess who “won.” A reorganized State Bank of Mound Bayou would open in 1915 but fail in 1924. The original monument of protest, the Delta Penny Savings Bank, failed in 1928. Both banks were victims of the economic downturn that cast its shadow on the Mississippi Delta years before Black Tuesday helped usher in the Great Depression. It would be three-quarters of a century before another Black bank opened in Mississippi: the New Orleans-based Liberty Bank opened a branch in Jackson in 2003.Footnote 84

Both the victory of the Delta Penny and the Mississippi Banking Law of 1914 reflected a bit of the bitter along with the sweet: Jim Crow reality and high-minded Progressive Era ideals. At the turn of the twentieth century, sensational accounts of corporate abuses and excesses riveted the public's attention. Protecting consumers through regulation ranked high on the agenda of social and political reformers. Progressive state legislators around the country felt compelled to protect consumers from the unrestrained interests of profit-minded corporations and executives, particularly from banks and bankers. Jim Crow reality translated into greater scrutiny and pressure on Black financial institutions. The monuments of protest envisioned by Wayne and Minnie Cox and other enterprising Black men and women in the early twentieth century demonstrated that Black men and women would use business and politics to challenge the deceptive logic of Black inferiority and efforts to consign Black people to the lowest rungs of society.

That the passbook and insurance policy could not stay the noose is clear. But a Black man patting in his pocket a faded passbook, its cover worn from years of use, or a Black woman gently smoothing a folded insurance policy certificate lain in a metal box alongside other important family keepsakes, posed a threat to the system of Jim Crow that should not be discounted or turned aside casually. The weight of a carefully tended passbook in the pocket was enough to add a few extra seconds before a Black man averted his eyes, snatched off his hat, and stepped off the sidewalk to give a white man or woman the right of way. Remembrances of a deeply creased, guilloched paper in a metal tin could add a few extra minutes before a Black woman responded to the ringing of a house bell not her own or to a white housewife shouting from another room to ask when lunch would be ready or some other household matter. While it is harder to see if one takes Mississippi's 1914 Banking Act or even the Great Depression as the end of an era, early-twentieth-century Black banks in Mississippi present a picture, however brief, of how Black people conceptualized and enacted their own economic freedom.