The year 2021 marked the bicentenary of the Greek Revolution and saw an increased interest in the revolutionary period throughout Greece, with many scholarly publications on the subject. Little noticed in 2022 was another bicentenary, affecting both the result of the Revolution and the region of Ioannina and Zagori in particular: the killing of Tepedelenli Ali Pasha (24 January 1822) by the Sultan's troops. Both cases are revealing of how the way the academy treated the commemoration of the 1821 bicentenary differs drastically from the attitudes of local communities and the perception of regional pasts.

Epirus, when it comes to Ali Pasha, highlights this contrast. For example, the international symposium on Ali Pasha and his Age, organized by the Municipality of Ioannina and including many prominent scholars of Modern Greek and Ottoman history, triggered nationalist reflexes on the part of a small yet vocal portion of the local community, with comments ranging from disgust to allegations of ‘treason’.Footnote 1

Under Ottoman rule, Epirus formed part of the province of YanyaFootnote 2 and Ali Pasha was the governor of the sancak between 1787 and 1822. During that period, our area of study, the Zagori of present-day north-west Greece,Footnote 3 thrived under the administrative Zagorisian League (Το Κοινό των Zαγορισίων) because many Zagorisian koçabası notables formed part of Ali Pasha's court. Furthermore, the architectural apogee of Zagori, as we know it today, dates to the turn of the eighteenth century and the rule of Ali Pasha. It was the mercantile networks maintained and secured by his rule and his client network that enabled the flourishing of Zagorisian notables and the channelling of their wealth into private and public building.

More importantly, it was a handful of Zagorisian notables who lobbied for installing Ali Pasha at Ioannina. During the unstable period preceding the rule of Ali, many local clansmen vied for control of the town. The notable families of Zagori, having mercantile and fiscal interests in a stable administration, came to an agreement with the notables of the town to rule together until a stable solution could be found,Footnote 4 while, as the folk song recalls, Zagorisians ‘Noutsos from Kapesovo and Paschalis from Constantinople brought Ali Pasha into the varoş.’Footnote 5 The importance of the local elites in establishing Ali Pasha in Ioannina is a point often under-emphasized in the historiography of the Ottoman period.

To return to the conference on Ali Pasha and his Age: much negative commentary appeared in the local press arguing that a commemoration of Ali Pasha had no place in the bicentennial commemoration of the Greek Revolution. One student from Zagori stated that Ali ‘was a cruel leader and his killing assisted in the successful outcome of the revolution [and] in a period when we need healthy values for our society. . . we should commemorate those whose contribution to the liberation of the Nation is indisputable.’Footnote 6

There has been more than half a century of scholarly research on the phenomenon of Ali Pasha.Footnote 7 A significant portion of his archives has recently been published in Greek with a seminal introduction by Vassilis Panagiotopoulos,Footnote 8 and the provincial rule of the ayans has been contextualized.Footnote 9 Yet, not surprisingly, school curricula continue to promote a reading of history close to the nineteenth century national historiography: a polarized discourse eliding the complexity of local history – in this case the distinctive Zagorisian League and its entanglements with the Ottoman administration – in favour of a simplistic and nationalist grand narrative.

In this rather disheartening context, the present contribution offers an alternative version of history concerning the minor elites of Zagori and regional settlement patterns, interpreting change from within. Α particular interest is shown here in the ways local elites affected changes from the fifteenth to the nineteenth century. Instead of asking how social and administrative structures affected the locality –and in an attempt to avoid the pitfalls of ethnography when it comes to approaching an era before the nineteenth century– the present article seeks to bring the agency of those dwelling in Zagori to the fore. We shall investigate the ways they adapted to changing circumstances –imperial and local– and how their actions affected the cultural landscape of Zagori.

For, if one side of the problem is the nationalist attitudes that emerged from the bottom up on the occasion of the bicentenary, the other is the absence of research on the microscale, which tends to get lost in efforts to synthesize without knowledge of local realities. Here the various ways in which localities affected structures offer different insights.

The case of Ali Pasha is not the first in which Zagorisians operated to appoint an acting ruler of Ioannina. According to the Chronicle of Ioannina, they marched to Santa Maura (Levkas) and escorted Carlo I Tocco to Ioannina in 1411, alongside the town's notables: at the time, this minor nobility was of a military character.Footnote 10 This article investigates the period between that incident and the intervention of the Zagorisian notables to install Ali Pasha as a governor in the Ottoman province of Yanya.

1. Methodology

An account shedding light on the overall period to the in-between centuries is in a position to argue that the local elites that appeared during the reign of Carlo I Tocco did not disappear only to emerge more than three centuries later with the installation of Ali Pasha at Ioannina. Indeed, it will be argued that such elites constantly adapted to the changing political and economic circumstances.

To tackle the issue, we have used a variety of sources. Ottoman registers from AD 1564–5 (TT350) and 1683–4 (TTK 28 & 32) have been examined in conjunction with local historical accounts (from the fifteenth-century Chronicle of the Tocco Footnote 11 to nineteenth-century local scholars)Footnote 12 and oral history. Landscape archaeology fieldwork to locate sites of interest discovered in the archives has also been implemented recently.Footnote 13 This intensive and interdisciplinary investigation of landscape on the microscale of montane Zagori, coupled with textual evidence and oral history, allows for a reading of the changes from the fifteenth century to the nineteenth from within.

2. Elites from Carlo I Tocco to the voynuks (fifteenth to late sixteenth centuries)

Since the time of Aravantinos (1870), it has been known that the town of Ioannina surrendered peacefully to the Ottoman army of Sinan Pasha. His letter addressing the notables of the court of the recently deceased Carlo I Tocco was recorded by Aravantinos and reproduced in recent scholarship, while the context of the development of the early Ottoman towns in Greece has recently been emancipated from more ‘traditional’ readings of history.Footnote 14

Sinan Pasha's letter addressed the ruling elite of the castle (Simeon Stratigopoulos and his son) and the religious administration.Footnote 15 According to Melek Delilbaşı, it is the earliest documented case of ahidnâme Footnote 16 in the context of amân, ensuring the continuity of the secular and religious status quo. Orthodox notables continued to manage their fiefs, adapting to the timar system while also maintaining their judicial rights. This process is in line with the Ottoman methods of conquest and elite accommodation in the regions surrendering peacefully to the empire.Footnote 17

The notables of Zagori who escorted Carlo I Tocco from his castle at Levkas to Ioannina in 1411 held their privileges, according to local history through another accommodating treaty, which Aravantinos named ‘Voinikio’.Footnote 18 However, as recently demonstrated through a comparison between Aravantinos’ list of villages ‘initially entering the treaty’ and the sixteenth-century Ottoman voynuk registers recorded in TT 350 and TTK 32, it appears that the list of Aravantinos has a terminus post quem in 1583-4, being in fact a fragmented voynuk register rather than the initial draft of a treaty.Footnote 19 Although we cannot rule out the potential of a separate treaty with the region of Zagori under the name ‘Voinikio’, what Aravantinos describes as a communal privilege is proof of elite adaptation from the court of Carlo I Tocco to the Ottoman administration as voynuks, auxiliary forces to the expanding imperial army.Footnote 20 This picture connects with the broader suggestion that voynuks were members of the pre-Ottoman minor nobility in the Balkans and, in some cases, retained part of their properties as timars in exchange for their military services.Footnote 21 In the instance of Zagori, we are fortunate to have the previous minor military elites recorded in the Chronicle of the Tocco, while in one instance a notable from Zagori was Michael VoevodaFootnote 22 Therianos, depicted as ktetor in the catholicon of the Hagia Paraskevi monastery in Monodendri village in 1414.Footnote 23

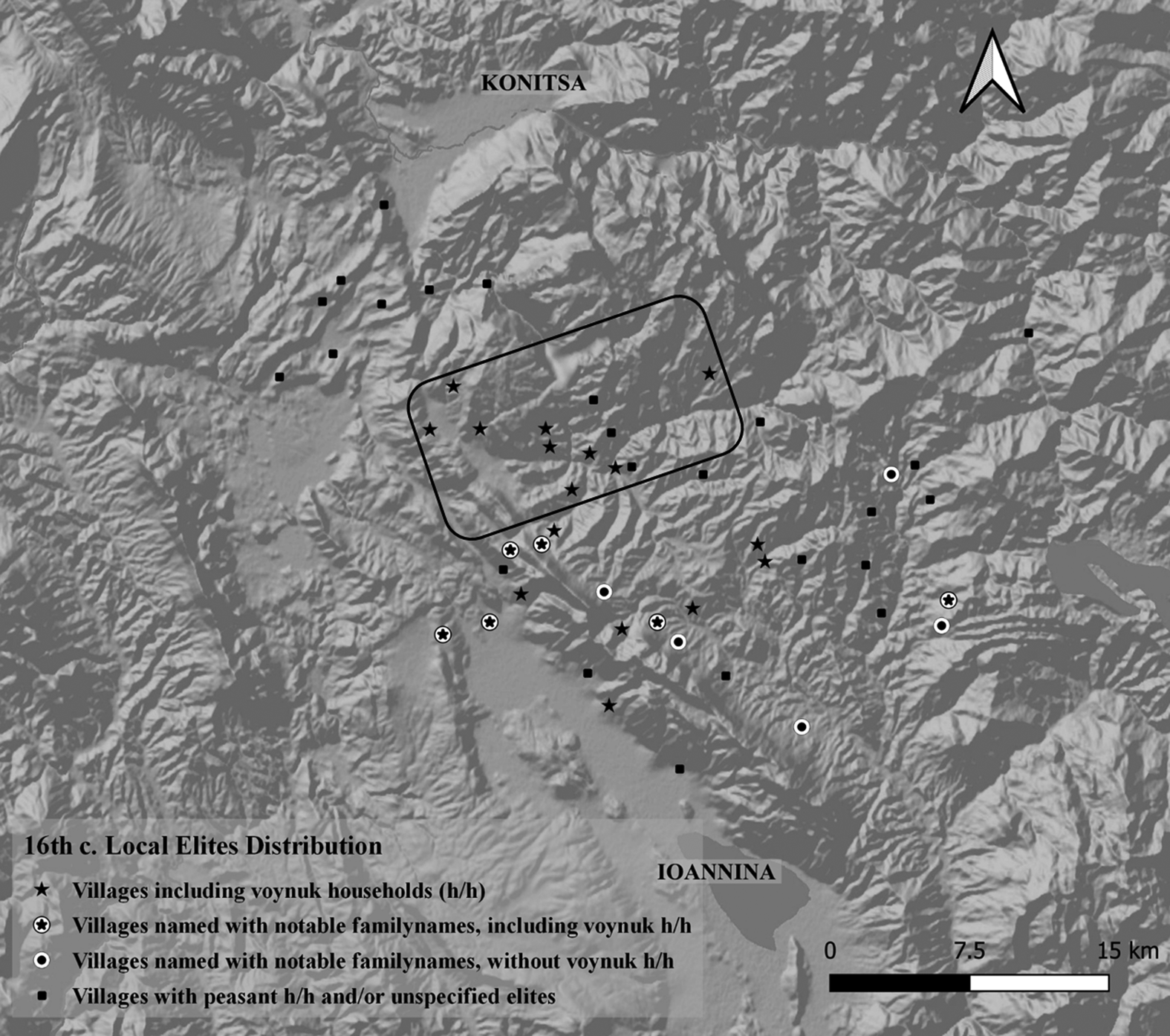

As seen on the map (fig. 1), the villages containing voynuks in the sixteenth century are situated along the main paths leading from Zagori to Ioannina and connecting Zagori with the area of Metsovo (to the east) and Konitsa (to the west). The voynuk villages of Dovra (today Ασπράγγελοι) and Bulcu (today Ελάτη) are on the main gateway to the mountainous regions of Zagori from the town of Ioannina: it is the same location that the military units of Zagori set out to meet the army of the Grand Constable (Μέγας Κοντόσταυλος) of Ioannina, join forces and defend the city against the army of Spata. As a result, the topographical distribution of the voynuk villages attest to the continuation of a minor military elite from Zagori into the early Ottoman administration.

Figure 1. Map showing the settlements of 16th-century Zagori and Papingo in relation to known elites. See below for an explanation of the annotated area (ESRI Shaded Relief, edited by Faidon Moudopoulos-Athanasiou)

Furthermore, as discussed below, the villages marked on the northern slopes of Mt Mitsikeli and in the Ioannina lowlands bear the names of sixteenth-century Ioannina notables. Consequently, we begin to grasp a local landscape with hierarchies and well-defined roles: voynuks are not only auxiliary military forces to the Ottoman army but also act as passage guards securing the vital regional pathways; on the lines of their function in the northern Balkan provinces, as members of the privileged group of askeri.Footnote 24

2.1 Accommodation and the topography of division

Therianos and his family had connections at the court of Carlo I Tocco, and this family legacy continued within the Ottoman administration. Two hundred years later, one of his descendants, another Michael Therianos, owned 6000 head of livestock from 1620 to 1635 in the same area,Footnote 25 while the local scholar Ioannis Lambridis argued that in the eighteenth century the family changed its surname to Misios, a well attested notable kin linked with the early modern cultural landscape of Zagori through many public edifices, among them, the Bridge of Misios (1748, Vitsa, Zagori).Footnote 26 These details support the historical sources arguing for the peaceful accommodation of Zagori, as well as Ioannina, into the Ottoman administration and the continuity of the local elite's privileges, mostly under the status of the voynuks.Footnote 27

Alongside local voynuk elites, the Ottoman administration would have had to accommodate sipahis as timar holders, while establishing the kanunname of Ioannina after the Ottoman conquest (1430).Footnote 28 A combination of archival research and landscape survey offers a hint at the topographical alterations that took place because of this condition.

Sixteenth-century registers record two villages (karye) in the western edge of Zagori, ruins of which have recently been identified: Hagios Minas and Rizokastro.Footnote 29 However, during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, at approximately the same location, the settlement of Revniko was positioned. It was an important site, according to the Chronicle of Ioannina, for regional defence against raids by ‘Albanians’ and ‘Turks’. The same source informs us that during the reign of Thomas II Preljubović (1367-1384), the villagers of Revniko marched to Ioannina and demanded investment in the defensive walls of the settlement. Even though Preljubović fulfilled their request, Revniko was ‘captured’ by Şahin Pasha in 1382.Footnote 30

The local scholar Lambridis suggested that the castle of Hagios Minas (Καστράκι του Αγίου Μηνά) was formerly known as Revniko.Footnote 31 However, both Hagios Minas and Rizokastro appear in the sixteenth-century registers and Rizokastro was evidently flourishing, as the building of the Evangelistria monastery (1575) indicates. Its catholicon includes the earliest appearance of a ktetor in the Ottoman context of Zagori, 161 years after the depiction of Michael Voevoda Therianos.Footnote 32

Older locals today refer to the extension of the mountain containing the ruins of the sixteenth- century village of Hagios Minas as ‘Rouinikos’, while oral history suggests that ‘Roinikos’ was the hill of Kastraki (or Rizokastro in the Ottoman sources), associated with the village of Hagios Minas (today, Καστράκι του Αγίου Μηνά). In the fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries, Revniko must have controlled the access to the fertile plain of Konitsa and to the limited fields of Doliana that were of paramount importance for the secure of surplus for the town of Ioannina – hence the need of the Grand Constable of the Chronicle of the Tocco to defend the region.

Since Revniko controlled both plains, it is reasonable to suggest that it extended to the administrative area of both Hagios Minas and Rizokastro in the sixteenth century. As it was contrary to the Ottoman method of conquest to destroy settlements in areas that assimilated peacefully to the empire, it is reasonable to assume that Hagios Minas and Rizokastro were the product of an administrative division of the larger settlement of Revniko. This practice suited the Ottoman administration in multiple ways: it helped allocate land to multiple sipahis and other minor elites, while also ensuring in this case that the two villages remained relatively small, to prevent political anomalies in such a strategic location. A similar logic of division was implemented for the entirety of the region of Zagori: the decentralized villages of Dovra, Negarades, Tservari, and Tsernitsa saw similar divisions in the sixteenth century.Footnote 33

At the time, the villages of Zagori were in general decentralized: the traditional touristic image we have inherited in the present, with the plane tree in each village square, is the product of post-seventeenth century socio-historical developments, as recent cultural-ecological research has shown.Footnote 34 Even when the centralized model was implemented, decentralized entities were not unknown: the settlements of Vitsa and Monodendri for example, were separated in the final centuries of the Ottoman era. Lambridis documented an earlier historical phase, when the village of Monodendri was the Upper Mahalle (Άνω Μαχαλάς) of Vitsa.Footnote 35

3. From the voynuks (fifteenth to late sixteenth century) to the League of Zagorisians (seventeenth to nineteenth century)

If the early Ottoman era in the region of Ioannina and Zagori in particular was characterized by elite continuity and a topography of division in order to accommodate local minor elites such as the voynuks and other timar-holders, such as sipahis, then the late sixteenth century and the subsequent period is marked by the conversion of some karye settlements into arable land, into monastic land and into çiftliks, while in the case of Zagori only one new village is recorded.

The wider seventeenth-century changes in the Ottoman administration, including the shift from the timar system to that of iltizam (tax-farming) and the change of the military practices of the Ottoman army with the rise of new systems of warfare led to the cancellation of the voynuks, whose services were in decline already in the sixteenth century.Footnote 36 The development of the ‘age of the ayans’, saw in Zagori the rise of the koçabası administrative unit known as the League of Zagorisians (Κοινό των Zαγορισίων).Footnote 37 Within this context of transformation, we notice three types of shifts within the settlement pattern of Zagori: neighbourhoods of decentralized settlements with voynuk presence in the sixteenth century become monasteries; entire karye villages with voynuk presence become çiftliks; and in one instance a new village was established.

In the following pages, we do not suggest that the elites in Zagori continued just as before, from the sixteenth to the eighteenth centuries, with the mere change of names from voynuks to kocabaşıs. Rather, we argue that the new historical circumstances of the seventeenth century affected the Zagorisian elites. The transformation is rooted in local adaptations, and there is no extant corpus of written documents to point to them. However, this absence of specific written sources does not imply absence of data, and our observations are based on landscape archaeology, survey, and the interpretation of the few sources available (see also Table 1 in section 4 below for a schematic summary of the suggested historical process).

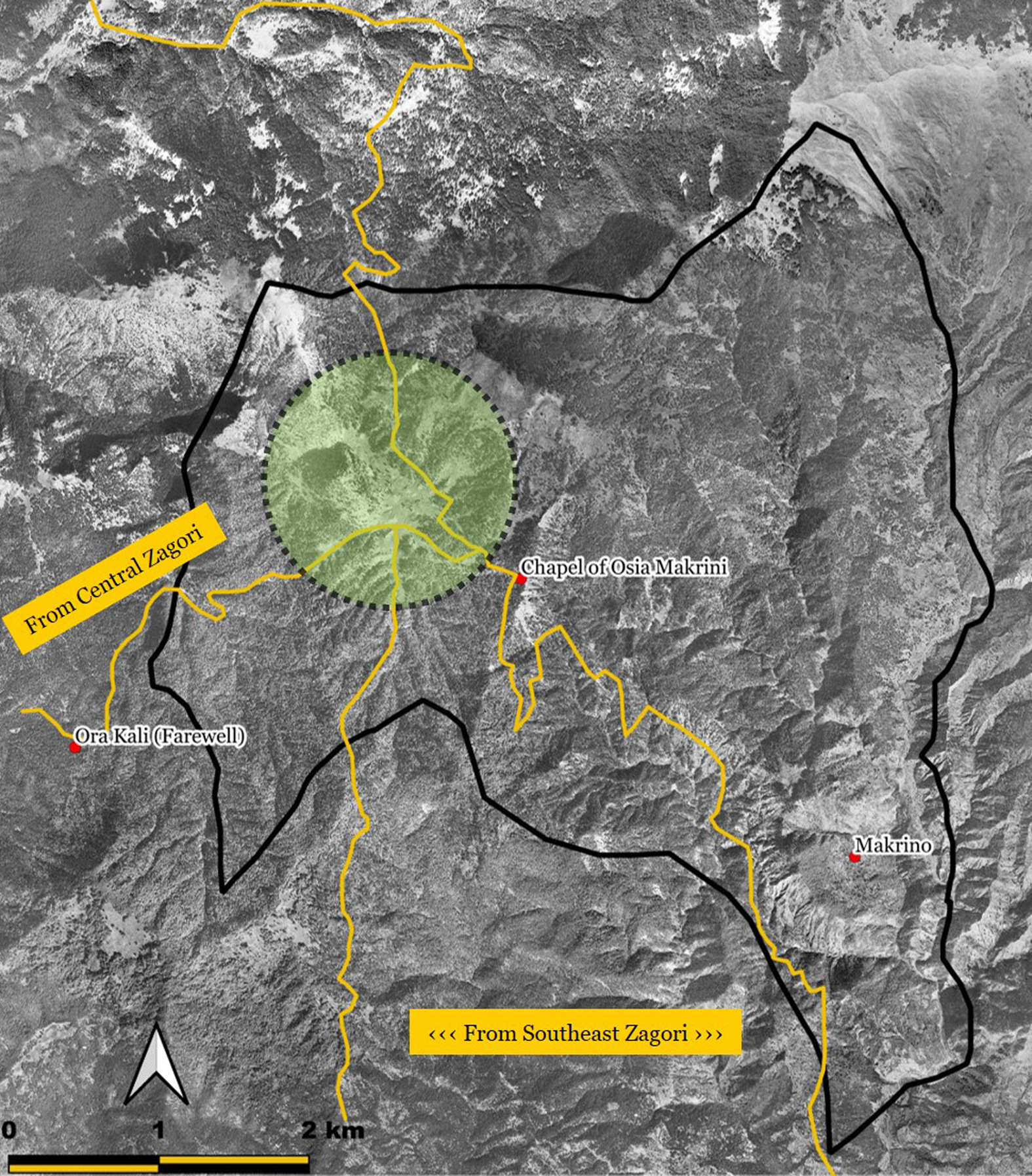

Table 1. Table showing the evolving adaptations of the local Zagori elites in the broader sociopolitical changes (15th–19th c.) (Faidon Moudopoulos-Athanasiou).

3.1 From settlements to arable, monastic, land (sixteenth to seventeenth centuries)

The village of MavrangeloFootnote 38 appears in the sixteenth-century Ottoman tapu registers as entirely populated by voynuk families.Footnote 39 According to local nineteenth-century sources, its abandonment led to an increase of population in of the nearby settlement of Dovra.Footnote 40 However, as argued elsewhere,Footnote 41 in fact Dovra, Dovra küçük (today, Κουτσοντόμπρι), and Mavrangelo were all part of the same decentralized settlement, divided for administrative and fiscal purposes by the timar system. In lieu of Mavrangelo emerged the monastery of Asprangeloi (c. 1600).

The village of Tsernitsa in the sixteenth century included voynuks and was divided into three timars. Before the Ottoman survey of 1564-5 the smaller of these, Tsernitsa Küçük was dissolved and reaya from the other two timars cultivated the arable lands of that area. These lands continued to be cultivated until the early twentieth century by peasants from Tsernitsa (today, Κήποι), but the area came later to be defined by the monastery of the Nativity of the Theotokos. Consequently, the smaller of the sixteenth-century neighbourhoods of Tsernitsa village, and the only one that did not contain voynuk families, was transformed into a mezra'a and subsequently the arable space was defined by the monastery.

A similar process is recorded in the now abandoned village of Stanades which housed voynuk families in the sixteenth century. On the dissolution of the village, the most fertile lands continued to be cultivated by the neighbouring reayas of Frangades and Liaskovetsi (today, Λεπτοκαρυά). However, these lands received ‘divine’ protection through the installation of the church Panagia Stanades and the monastery of Hagios Nikolaos, which was tied to the village of Frangades and managed the said fields.Footnote 42

3.2 A new karye settlement of the sixteenth century: Makrino and the notable Makrinos

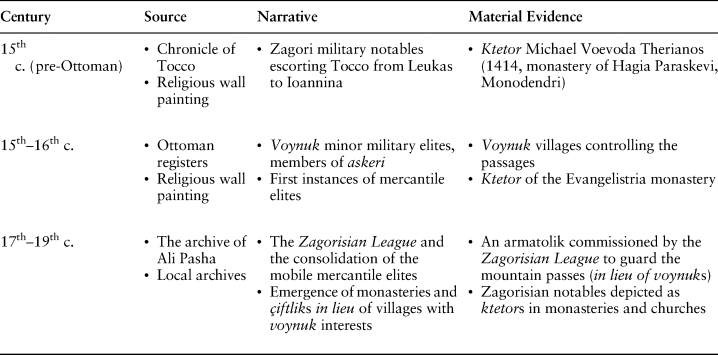

The karye village of Makrino was marked as hariç ez defter (newly inscribed in the register) in 1564–5. It had, then, been established during the interval between the registers of 1530 and 1564. Within the twenty-year interval from the registers of 1564 and 1583, the small village was inscribed a yaylak summer pasture named Ikserovouni (Gr., Ξεροβούνι = dry mountain). However, it is rather odd for a small village of 25 hane households and 11 mücerred unmarried individuals to have a summer pasture generating income significant enough to be registered in the cadastre. The only other monetized yaylaks of Zagori and Papingo in the sixteenth century occurred in the wealthiest villages of Ağlitonyavista (today, Άνω Κλειδωνιά) and Papingo.

The case of Makrino allows for some interesting observations on the microscale. The name of the village is related to Makrina the Younger (Οσία Μακρίνα, AD 330–79), sister of St Gregory of Nyssa, and the chapel situated at the summer pasture is dedicated to her.Footnote 43 Furthermore, according to Aravantinos, the notable family Makrinos prospered at the castle of Ioannina among other notable Orthodox families in 1542 (see section 4 below).Footnote 44

Consequently, the Ottoman registers recording the establishment of the village Makrino (c. 1564) and the establishment of its yaylak, Kserovouni (ca. 1583) reflect an elite perspective, and the names of these resources are Greek.Footnote 45 By contrast, the toponyms for the agropastoral taskscapes of the village are predominantly Vlach.Footnote 46

This contrasting image reveals an interesting interplay between early Ottoman Orthodox notables in the town of Ioannina and the subaltern Vlach peasants of mountainous villages of Zagori. Makrinos, according to this contextualized investigation drawing on Ottoman registers and local toponyms, established a village of sedentary Vlach mixed-farmers and herders.Footnote 47 However, these twenty-five families would have been in no position to administer a monetized yaylak on their own.

Topography and the analysis of the mountain passes of Zagori offer additional information. Makrino, and subsequently its yaylak, were established in a power vacuum, in an area with no settlements near the village. However, its yaylak, the area where the chapel of Makrina the Younger is located, is at a nodal point of the mobility network of montane Pindus. In fact, it is precisely at the point of the summer pasture that three transit routes merge into a single pathway leading northwards (fig. 2). The notable established his sovereignty in a mountainous territory void of habitation, securing for his activities an extensive summer pasture, while simultaneously controlling a node in the early modern mobility network.

Figure 2. The location of the summer pasture (yaylak) of Makrino and the relevant mobility routes (HMGS aerial image, 1945, edited by Faidon Moudopoulos-Athanasiou)

3.3. From karye villages to çiftliks (eighteenth century)

In other instances, karye or voynuk villages recorded in the sixteenth-century registers became çiftliks, either absorbed by nearby monasteries or as a result of other parameters related to regional renegotiations of power, as shown below. In the case of monasteries,Footnote 48 one instance is the village of Vuça (in contemporary oral history: Μπότσα). The sixteenth-century registers recorded it together with the monastery of that name. The village was to dissolve later, while the monastery – alongside the neighbouring village of Greveniti in eastern Zagori – thrived in the later Ottoman context (especially from 1750 on).Footnote 49

A similar case is to be found in the western part of Zagori, with the emergence of the Speleotissa monastery (1644). By1752 the monastery had gradually purchased most of the lands belonging to the settlements of Hagios Minas and Rizokastro discussed earlier, buying it off from Orthodox reaya and Ottoman beys.Footnote 50 Within this period, the villages of Hagios Minas and Rizokastro were abandoned and a new village under the name Hagios Minas had emerged in the lowlands, housing the sharecroppers of the Speleotissa monastery. The formerly important karye settlements of Hagios Minas (has) and Rizokastro (zeamet) of the sixteenth century, gave way to a çiftlik settlement on a lowland area near the fertile fields of the monastic land. The neighbouring village of Mesovouni emerged in the eighteenth century as well, to house sharecroppers of the monastery.

Although the characterization of monasteries too as regional Ottoman elites is not new,Footnote 51 what is of particular interest in this case is that the Orthodox koçabaşı notables of the nearby village of Artsista (today, Αρίστη) –which was a has in the sixteenth century– appear to be managing the resources of the monastery together with the monks, earning half of the revenues.Footnote 52 This dynamic provides a further hint at an active local elite, especially in the context of the provincial ayan administration of Ioannina from the seventeenth century to the early nineteenth.Footnote 53 While former important settlements Hagios Minas and Rizokastro were gradually converted into çiftliks, their neighbour, Artsista, from a has property became an Orthodox community, whose local kocabaşı elite co-managed the revenue from the monastic share-cropping fiefs.

This close interplay of the religious institutions with regional secular minor elites is of particular interest. Combined with the transformation of voynuk villages into monastic lands (see 3.1), this enables us to discern the workings of a latent minor-elite agency in the change of the spatial dynamics of the region.

Monasteries turning the arable land of karye into çiftlik estates is one reality. Zagori records villages consisting of solely voynuk families in the sixteenth century registers (Protopapa and Peçali) that become çiftlik estates before the turn of the eighteenth century.Footnote 54 Figure 3 shows the location of these two villages in the plain of Ioannina, together with their arable fields, in 1945. In contrast to the rest of the mountainous Zagori, these villages are on a lowland setting facilitating sharecropping and extensive surplus agriculture, rather than the intensive polycropping model applied in the mountains.Footnote 55

Figure 3. Aerial image showing the plots of Protopapa and Petsali (HMGS, 1945, edited by Faidon Moudopoulos-Athanasiou).

Aravantinos informs us that, alongside Makrinos, the notables Protopapa(s) and Petsali(s) prospered in the castle of Ioannina in 1452.Footnote 56 These details offer another explanation for the rise of certain çiftliks in the region, besides reaya bankruptcy or other reasons related to the rise of the iltizam tax-farming system. Alongside the elimination of the voynuk askeri status, some of the former voynuk notables transformed their lowland villages into çiftliks, adapting to changing macroeconomic circumstances.

4. Elite continuity and changes from within

As noted in the introduction, the notables of Zagori are known from just two historical sources: from their march in 1411 Santa Maura (Levkas), alongside Simeon Stratigopoulos of the castle of Ioannina, to escort Carlo I Tocco to the town, in the period immediately preceding the assimilation of Ioannina to the Ottoman Empire; and at the turn of the eighteenth century, when they administered the area together with the notables of the Ioannina varoş. We enquired whether the intermediate period in between the pre-Ottoman and late-Ottoman context is any different and whether these elites affected change on a regional level or were passive observants of wider historical change.

4.1. From the early fifteenth to the end of the sixteenth century

Investigating the local landscape closely, we found more evidence of the minor elites of Zagori, which adapted to the Ottoman status quo through the voynuk privilege (Table 1).

Through Aravantinos we acquire the information that in the mid-sixteenth century, the notable families of Protopapa, Petsali, Boulsou, and Makrino thrived in the castle of Ioannina, alongside the pre-1611 Orthodox community of the town. The first three notables owned villages of Zagori inhabited only by voynuk families in the sixteenth century, while Makrinos –as we have seen– established a village in the middle of that century at a strategic position in the mountains profiting from its summer pasture and controlling a particular node of the late medieval/early modern mobility network.

Furthermore, we have calibrated the above image with topographic evidence. We have argued that the early Ottoman administration divided large decentralized settlements into smaller entities to accommodate sipahis, local elites, and other timar holders in the peacefully assimilated region. The case of the fort of Revniko, which was to be divided into two villages, Hagios Minas and Rizokastro, as well as the instance of Dovra, eloquently demonstrates this.

4.2. From the early seventeenth to the end of the eighteenty century

If the eighteenth century closes with the Zagorisian notables and the Varoslides collectively administering the town of Ioannina and seeking for a powerful leader, the beginning of these developments is the establishment of the Zagorisian League. Although we lack the sources to point at the exact year of the emergence of this kocabaşı administrative model, it is worth situating it in the wider chronological evolution of the Zagori cultural landscape.

If we return to Fig. 1, the first layer represents the voynuk villages, while the overlay indicates the villages that subsequently formed the core of the Zagorisian League. If we remove the voynuk villages of the plains that became çiftliks, we notice that the concentration of the minor elite topography remains the same. However, the pre- and early-Ottoman military privilege is transformed into economical (entrepreneurial and tax-farming), in the context of the rise of the ayan administration. The military obligation of the voynuks is reflected in the ‘obligations’ of the League, among which lie the requirement to assemble an armatolik force of one hundred and fifty men at arms to guard the mountain passes –a job that in the previous centuries would have been the duty of the voynuk families.

The case studies addressed in section 3 have revealed three different ways in which local elites reacted to the macroeconomic shifts affecting the topography of Zagori. Monasteries emerged absorbing the land of abandoned villages, voynuk settlements were transformed into çiftliks, and villages of voynuk interest were abandoned, cultivated by villages from neighbouring settlements, while the arable land belonged to religious institutions. Finally, in the case of Makrino, a single village was established, facilitating the mobility network. Within this milieu, it is reasonable to suggest that the local elites of Zagori, well connected because of their earlier voynuk and other privileges, saw their transformation into the administrative League of Zagorisians, of tax-farming and mercantile interests. This is to be understood as an organic, rather than a conscious or directed, process. However, the balance of the topographical, archival, and broader historical evidence argues for the presence of a local elite throughout the Ottoman period in Zagori, a presence which only ceased during the Tanzimat reforms. Until then, local notables remained active agents inflicting change within the mountainous area around Ioannina, though historians’ desire to investigate changes in the macroscale has downsized their importance.

Epilogue: a note against a neo-orientalist reading of history

The national historiographical myth that during the Ottoman advance in the southern Balkans the Greek-speaking population fled to the mountains to escape their oriental overlords has long been debunked.Footnote 57 Through the case study of the notables of Zagori, we have stressed the continuation of pre-Ottoman minor military elites into the early-Ottoman administrative system (voynuks). We have shown that they influenced the changes both in the lowlands (Ioannina) and the mountains (Zagori), and that they showed adaptability in the changing socio-political circumstances through the centuries of the Ottoman rule. We hope that this will be a spur to further interdisciplinary endeavours when it comes to researching the Ottoman period in Greek lands.

In a ‘Wall Street Journal Book of the Year 2018’ on Epirot music, focusing particularly on Zagori, the author argued –among other things– that ‘the blackest, most brutal epoch for Epirus occurred when the Ottoman Turks captured Ioannina in 1430.’Footnote 58 According to one review of the book, it is ‘[i]n the tradition of Patrick Leigh Fermor’,Footnote 59 and although much has changed in academia since the lonely walk of the white male foreign savant, award winning books still reproduce stereotypes of national historiography, assisting –probably unconsciously– in the development of neo-orientalist narratives.

Studies like the present one ought to act as embankments against the evolution of neo-orientalist paradigms in the quest to ‘rediscover the most ancient music of Europe’ or any other pseudo-historical narrative.

Faidon Moudopoulos-Athanasiou is a Juan de la Cierva postdoctoral fellow at the Landscape Archaeology Research Group, Catalan Institute of Classical Archaeology. He holds a PhD in Archaeology (University of Sheffield), where he investigated the archaeological landscape of early modern Zagori (northwest Greece). At that time, he was a scholar of the White Rose College of the Arts and Humanities (AHRC) and of the A.G. Leventis Foundation. His research interests include Mediterranean archaeology, landscape archaeology with a particular interest on the Ottoman period, and the history of archaeology.

Elias Kolovos is Assοciate Professor in Ottoman History in the Department of History and Archaeology at the University of Crete. He is the elected Secretary of the Board of the International Association for Ottoman Social and Economic History. He has written, edited, and coedited 16 books and over 70 papers in Greek and international publications and journals. His research interests include Mediterranean economic history, the history of the insular worlds, the history of frontiers, rural and environmental history, as well as the spatial history and legacies of the Ottoman Empire.