To Ruth Macrides

Arise, and go down to the potter's house, and there I will cause thee to hear my words. (Jeremiah 18.2)

In the past few decades, the fields of Byzantine, Ottoman and Early Modern ceramic studies have experienced extraordinary change: they have passed, somewhat abruptly, from the stage of stylistic classifications and dating catalogues to that of socio-economic analysis.Footnote 1 In this way, medieval and early modern pottery can finally aspire to achieve the importance its counterparts hold in other (pre-)historical periods and parts of the world, within the framework of processual and post-processual theoretical archaeology.Footnote 2 The present article is a case study within the interpretative framework of current archaeological thought: based on solid evidence from over sixty years of excavations, it examines, albeit summarily, the ceramic record of the town of Chalcis in Euboea, over a period of approximately eleven centuries, as an element directly affected by the social and political conditions the city witnessed (organization and interactions, technology, trade and exchange). For every stage along this longue durée, the contextual evidence of the pottery reveals conceptual models, cultural inferences and insights into the – otherwise unknown – daily lives of the town's inhabitants.

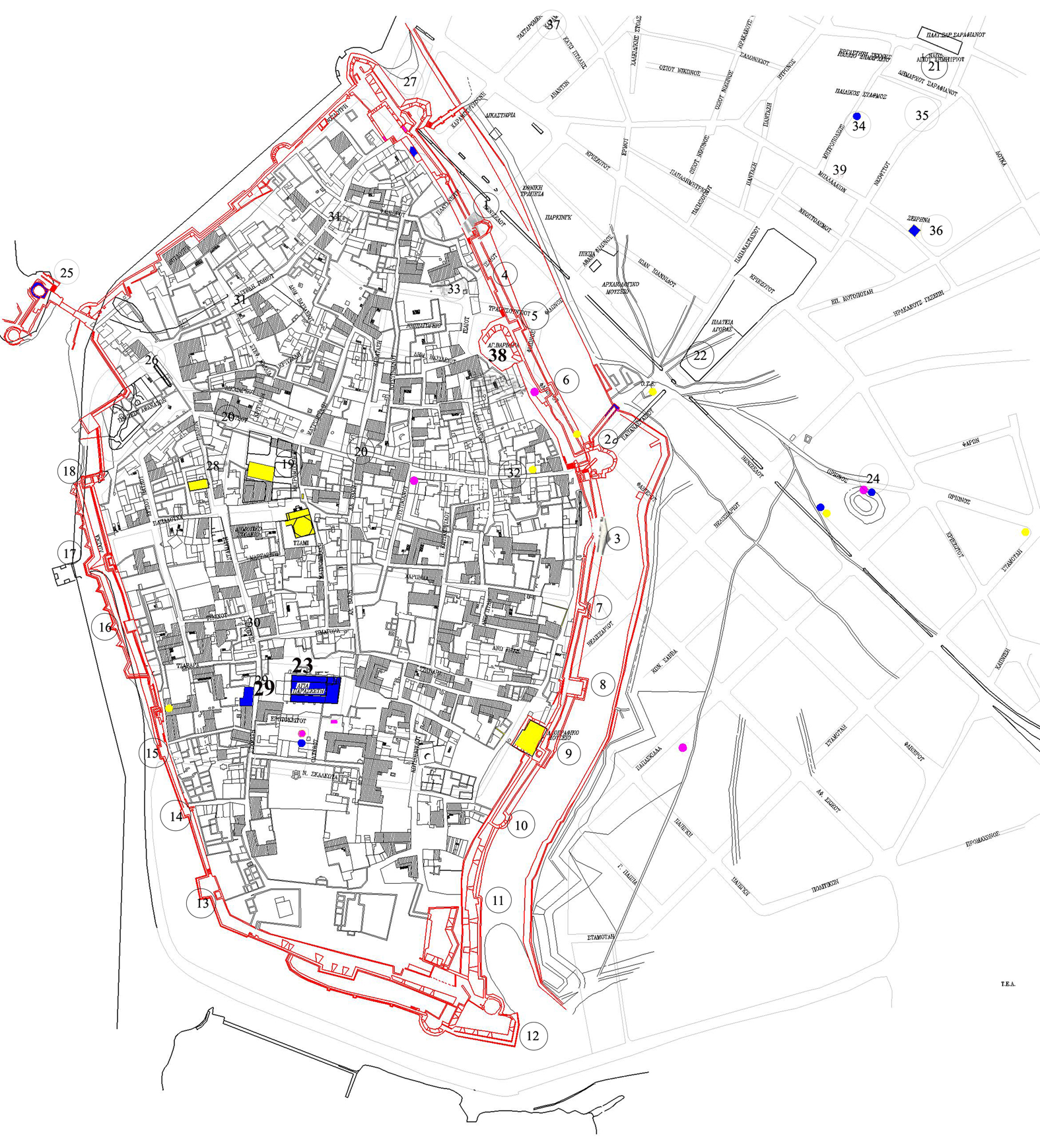

The interest in the case of Chalcis stems from the presence of two constants and two variables. The first comprises the civic environment and the local ceramic production; the second includes the fluctuating ceramic imports, along with the changing political and socio-economic conditions. In this way, the paper's focus extends from the early ninth century, when the walled town was established (or rather relocated to) its current position (Fig. 1), up to the early twentieth century, when the destruction of the medieval walls completed the urban transformation. Questions pertaining to the urban fabric, the neighbourhoods and the human topography both within and outside the walled boundaries have been addressed.Footnote 3 Furthermore, multi-disciplinary research has documented uninterrupted large-scale pottery manufacture, something noted independently by scholars on ancient periods.Footnote 4 This production, stemming from the proximity of rich clay beds in the adjacent Lelantine Plain, and facilitated by the existence of natural harbours, was in each period oriented to meet diverse needs: for transport vessels of agricultural products, for bricks used in construction, for tableware or for any other utilitarian vessel that could be formed out of clay, in the era before the invention of plastic.

Fig. 1. Plan of Chalcis. Source: Archive of the Ephorate of Antiquities of Euboea.

1. Eleutheriou Venizelou Street, walls.

2. Porta di Cristo, Upper Gate, Papanastasiou Street.

3. Mardochaiou Frizi Street, walls and tower.

4-8, 10-11, 13-18. Towers.

9. Tower and Folk-art Museum.

12. Rivellino di Burco.

19. Plateia Pesonton Opliton with Emir Zade mosque and underground cistern.

20. Kotsou street.

21. Ayios Dimitrios.

22. Market Square.

23. Ayia Paraskevi.

24. Orionos Street.

25. Fort of Euripos Bridge.

26. Plateia Athanaton with Porta di Marina and Rivellino di Mollini.

27. Rivellino with Lower Gate.

28. Paidon Street.

29. The Bailo House.

30. Stamati Street.

31. Aggeli Goviou Street.

32. Kotsou Street, Synagogue and Sultana Negrin plot.

33. Isaiou and Trapezountiou Streets.

34. Mitropoleos Street.

35. Ottoman hamam.

36. The Seirina Tower.

37. Ayios Nikolaos.

38. Ayia Varvara.

39. Balaleon Street.

Through the close examination of the various forms and qualities of ceramics (local vs. imported), we can trace the repercussions of economic activity for the social fabric of Chalcis, under the influence of fluctuating historical conditions. Following a regional and temporal perspective, focusing on what the diverse ceramic spectrum of each century can reveal about the local community, we hope to trace the distinct character of the city and to alter the rather generic historical accounts presented by earlier research.Footnote 5 In this way, we may offer a paradigm to enrich the growing field of Mediterranean studies.Footnote 6

From the ninth to the eleventh century

The rather meagre historical record for middle Byzantine Chalcis – then known as Egripos Footnote 7 – is enriched greatly by the material from the excavated clusters of this period, both within the walls (Ayia Barbara Square, Fig. 1.38, and the Ayia Paraskevi area/Toulitsi plot, Fig. 1.23) and outside (the Orionos plot, Fig. 1.24). The ceramic finds of this period are relatively uniform across the areas and include a variety of imported and locally produced wares. Imported pottery consisted mainly of tableware, including Constantinopolitan high-quality white ware variants in multiple forms and decorative patterns. The latter were not randomly brought isolated pieces, but rather represent a steady flow of commodities sold in Chalcis for local consumption, obviously destined for people of a certain financial and social standing.

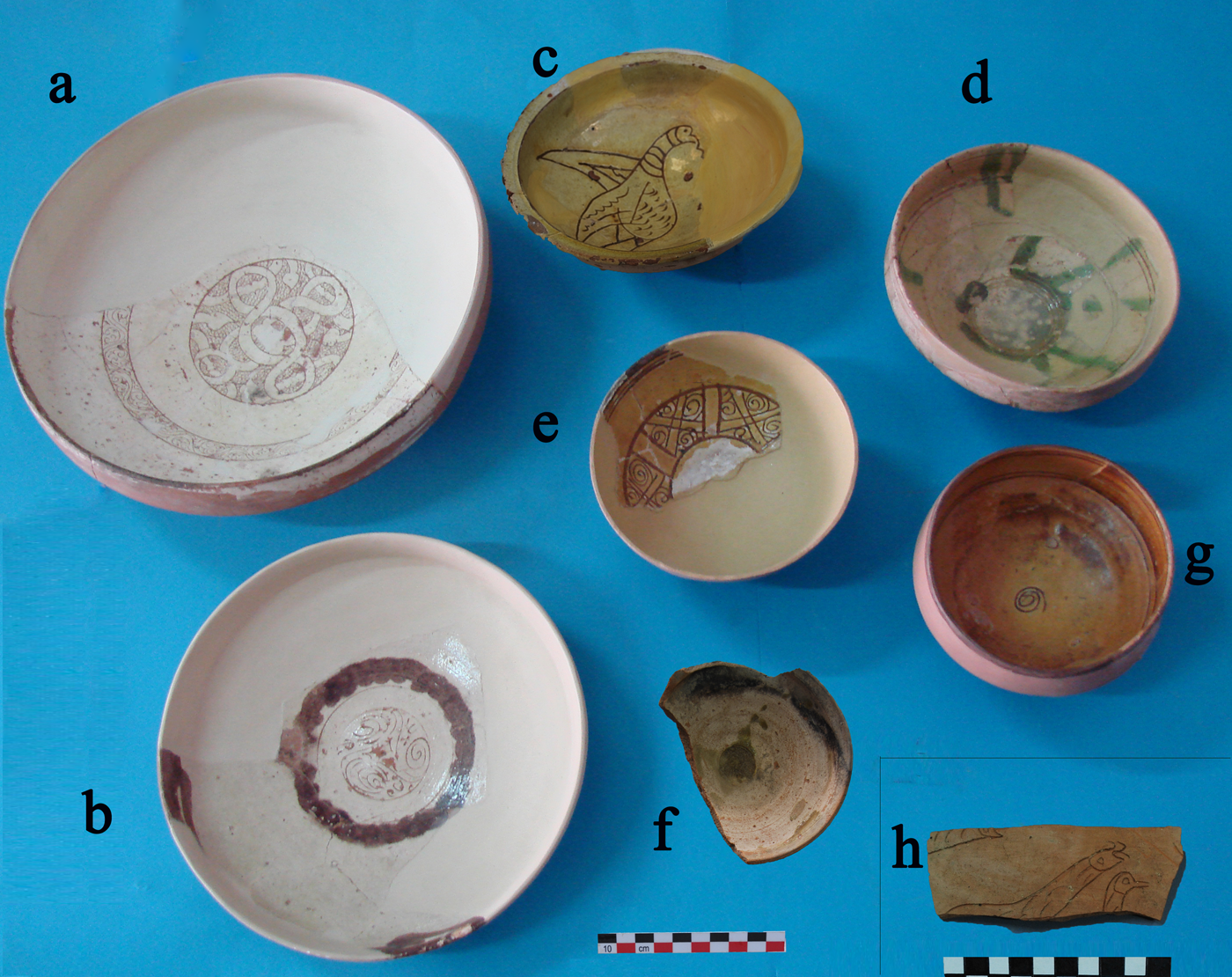

Local wares were used for domestic purposes, mainly for serving and transporting liquids or for preparing and storing food. Among them the group of incised unglazed wares stands out (Fig. 2h): it includes tableware, storage vessels, amphorae and a variety of other objects, such as a ceramic box. Their large quantities, range of shapes and decorative motifs show the vitality that this industry had already acquired; it also proves that these were affordable products, destined to cover everyday needs for the bulk of the population. Their local origin has been confirmed by chemical analysis,Footnote 8 showing that Chalcis workshops were among the earlier producers of this incised pottery, before the emergence of its glazed equivalent.

Fig. 2. a-d, f-h: local pottery, 10th–14th century; e: imported pottery, late 13th–14th century. Source: Archive of the Ephorate of Antiquities of Euboea. Photo: the authors.

When it comes to the amphorae for the storage and commercial transport of agricultural products, such as oil and wine, we find a similar picture for both local and imported wares. Chemical analysis has verified the existence of two groups, based on their provenances, both part of the same common Byzantine type known as Günsenin IIa.Footnote 9 In addition to imports from a yet unidentified workshop, there was a large group of locally made amphorae, obviously containing the produce of Euboean countryside.Footnote 10 Agricultural products must have been brought to the city and destined either for local consumption or for more distant markets, following a network of maritime connections. There is, therefore, a production pattern which, for this period, is also encountered in a few other important agricultural regions of the empire that exported their agricultural surplus in locally made vessels, such as Ganos in the Sea of Marmara.Footnote 11

For the period under discussion we, therefore, envisage Chalcis as a town that served as an outlet of regional agrarian production and as a producer of industrial goods (pottery, at least) for use in the central Greece market (primarily Thebes). It received various goods in its ports and circulated them to the rest of the province; these goods included agrarian products from other regions of the empire, as well as higher quality tableware – the trademark of the capital's production. Chalcis was therefore part of interregional networks beyond central Greece, sharing production standards and transport practices with the empire's internal markets. The wealthier residents of Chalcis had access to more refined products and apparently enjoyed a quality of life similar to those who resided in the capital. These residents, whether local or administrators who were posted to the city, certainly formed part of the local aristocracy and lived, along with their households, within the walls and sustained their links both to the imperial centre and to the regional capital (Thebes).Footnote 12

From the late eleventh to the mid-thirteenth century

From around the late eleventh century, industrial activity in Chalcis became more dynamic and reached unprecedented levels of production. The vitality of this period was reflected in the topography of the town, both within and outside the walls, with material found in far more areas than before, typically adjacent to those mentioned above.Footnote 13 Furthermore, the clearly larger quantities of excavated material, even in plots without built remains, reflects the significant growth and vitality of the population, in density and numbers, as well as in economic activity. Architectural sculpture from various extant churches that must have dotted the urban fabric, reveals close artistic affinities with nearby Thebes.Footnote 14

As far as pottery is concerned, local manufacture during this period reached a peak of self-sufficiency and was strongly oriented toward exports. Tableware included various decorative categories, such as ‘Slip-Painted’, ‘Green and Brown Painted’, ‘Fine Sgraffito’, ‘Painted Sgraffito’ (Fig. 2a–b), ‘Incised Sgraffito’ and ‘Champlevé’, for which all (regardless of provenance or decoration style) we have collectively proposed the name ‘Middle Byzantine Production’ (MBP), with Chalcis as one of the main production centres (main MBP). The city workshops produced on a mass scale, creating products destined chiefly for export: the maritime routes departed from Chalcis towards the southern Euboean Gulf and the open Aegean and extended around the eastern Mediterranean and the Black Sea. Transport over these networks is attested by the chemical analysis of an array of finds from Chalcis and coastal sites around the eastern Mediterranean, as well as from shipwrecks (such as at Kavalliani, Kastellorizo, Alonissos, Crimea).Footnote 15 Alongside these, we have also detected small quantities of imported Spatter Ware (Fig. 3, right), known from excavations in other parts of central Greece, such as Corinth;Footnote 16 further research on this material may define the nature of connections between regional workshops.

Fig. 3. Zeuxippus ware (left), first half of 13th century; Spatter Ware (right), 12th century. Source: Archive of the Ephorate of Antiquities of Euboea. Photo: the authors.

Chalcis’ ceramic production was export-oriented in this period; so too was amphorae production. Most of the amphorae can be categorized under the so-called Günsenin III type.Footnote 17 The amphorae numbers point to an equally impressive local wine and oil production, enough to cover local needs and probably also to be exported through the same maritime network as tableware. Furthermore, we may suggest that Chalcis played an important role in the evolution of pottery shapes and decoration, which can be traced both in tableware (from the unglazed incised wares to the glazed ‘MBP’ wares) and amphorae (from ‘Günsenin II’ to ‘Günsenin III’, through a local transitional type).

It seems, therefore, that during this period Chalcis held a vital role in interregional economic activity, obviously in connection to the administrative capital of Thebes. Furthermore, the same level of prosperity has been attested in the archaeological record not only in the two towns but also in the countryside around each.Footnote 18 Indeed, this was an era of transformation for central Greece, with local forces gaining particular prominence, either as landowning families or as local archontes. We have ascertained the names of some of these families and individuals, many of whom made their way to the imperial court and the higher echelons of the secular and religious administrations.Footnote 19 Furthermore, the existence of large monastic foundations in both Boeotia and Euboea, built with considerable artistic aspirations and supported by the intense exploitation of agricultural resources, seems to reflect the condition of equally wealthy landowners.Footnote 20

Research, which has thus far concentrated on silk fabrics and pottery, has shown that the products of the Thebes-Chalcis network played an important role in the eastern Mediterranean markets; one that they kept at least until the middle of the thirteenth century. Their agricultural or industrial commodities were distributed to the rest of the empire through the Chalcis port. This dense network of economic transactions must have been built on the collaboration of various groups of workers, artisans and merchants and on the motivations of a dynamic class of local magnates who provided the necessary funds and resources. In this way, David Jacoby's brilliant interpretation of the production system of the famous Thebes silk fabrics should be seen as encompassing more facets of the economic life – it was certainly valid for pottery manufacture.Footnote 21 We should also see these networks as social and political activity, since they presuppose a series of initiatives that clearly required the agency, authority, acceptance and collaboration of all local actors.

In the case of pottery, these people obviously took advantage of the political upheavals of the second half of the eleventh century in the Byzantine empire; the calamities that befell the Asian provinces seriously disrupted the commercial distribution networks that had functioned well in the previous period. Ceramic products coming from the capital virtually disappeared from the Aegean markets. This political and economic vacuum provided an unprecedented impetus to the regional industrial/pottery production of Chalcis, which specialized both in the export of refined tableware (MBP), as well as in transport vessels (amphorae) for agricultural products.

The late twelfth to mid-thirteenth-century conditions

The production and distribution of MBP ceramics (Fig. 2.a–b) continued on a large scale, at least up to the middle of the thirteenth century;Footnote 22 the evidence from excavations at Chalcis and Thebes is strongly reinforced by finds in many other places, including Corinth. In addition, the use of Günsenin III amphorae during the early thirteenth century suggests a continuity in the transportation standards and the trade networks of local agricultural products.Footnote 23 For example, in 1214 Nikolaos Mesarites, while on a diplomatic mission in the Latin Patriarchate of Constantinople, was offered a pungent wine from Euboea.Footnote 24 An interesting case of reciprocal relations with the area of (Latin-held) Constantinople is the presence of a few examples of the so-called ‘Zeuxippus Ware’ bowls in both Chalcis (Fig. 3, left) and Thebes.

Despite the political upheavals from the end of the twelfth to the early thirteenth century, the Chalcis-Thebes production and distribution network continued unhindered until the mid-thirteenth century; this extraordinary situation contradicts the pivotal importance usually attributed to the Fourth Crusade and the unravelling of the Byzantine state. Indeed, historical conditions and local responses seem to have been more complex than a mere disaster story brought about by external enemies. As early as the end of the twelfth century, the two towns cut their links to Constantinople and submitted to the local magnate, Leo Sgouros.Footnote 25 After 1204, they came under a new political authority (first the Latin Kingdom of Thessalonica, then the Latin Empire of Constantinople) and became seats of feudal entities. The change in the urban landscape of Chalcis (now progressively known as Negroponte) was evident through the building of a new power base that controlled both the settlement and the vital naval route of the Euboea Straits: a castrum, whose exact location and later history are still debated.Footnote 26

Yet the archaeological record of Chalcis (both architectural and ceramic) strongly supports the idea of an uneventful continuity throughout this period. The local population apparently chose accommodation and self-preservation rather than remain loyal to a lost Byzantine cause. This is how we may explain the seemingly peculiar fact that the two cities (Chalcis and Thebes) abandoned Leo Sgouros and swiftly submitted to Boniface of Montferrat, king of Thessalonica, and then joyfully received the Latin emperor Henry on his visits to Thebes and Chalcis in 1209.Footnote 27

From the mid-thirteenth century to 1470

From approximately the mid-thirteenth century, the town gradually turned into an important commercial port of the Venetian maritime network. Following a series of local conflicts in the second half of the thirteenth century (with the prince of Achaea, William II of Villehardouin, and the Byzantines under the knight Likario), the Venetian presence was consolidated through the Serenissima's representative, the bailo (Fig. 9). After 1390, both the city and the island became a territory directly ruled by Venice. The importance of the city for Venice is directly related to the global geo-political change that followed the creation of the Mongol Empire: the Aegean became part of a global trade route – the so-called Silk Road – and Chalcis was an important port of call along that route.Footnote 28

The urban topography of this period is far better known than the previous periods for multiple reasons: a) the historical work of David Jacoby and Pierre Mackay, who were able to differentiate neighbourhoods (within and outside the walls), districts, landmarks (both preserved and lost, secular and religious), wall gates, street networks and commercial arteriesFootnote 29; b) the study of still-standing buildings, such as the Dominican Church (the modern Ayia Paraskevi) and the Venetian public building known as the ‘Bailo House’ (Fig. 1.29)Footnote 30; and finally c) the extensive excavated remains, both within the walled area (for example, along the main commercial thoroughfare, which today is known as Kotsou Street, Fig. 1.20) and outside the walled area (Fig. 1.24, 34, 39).Footnote 31

The new political and socio-economic circumstances can be illuminated through the study of the ceramic record. This is evident both in locally manufactured and in imported vessels. In both groups the influence of the Venetian commercial and maritime network drastically altered the available products. More specifically, the tableware imports predominantly reflect the shipping lines that stopped in the city while crossing from Italy to northern Greece and vice versa: from northern Italy, the ceramics included Archaic Maiolica, Veneto Ware, Polychrome and Renaissance Sgraffito; from southern Italy, Protomaiolica and the known as RMR; and from the northern Aegean, they included wares from Constantinople and/or Thessaloniki (Fig. 2.e), Serres and Lemnos. Finally, specimens from Cyprus, Anatolia (Miletus Ware), Spain (Lustre Ware) and Mamluk territories (Syria or Egypt) were likely part of the Venetian cargos and meant to highlight the extent of their maritime network.

Chalcis’ local manufacture and prominence as an interregional production centre shrank because it was cut off from Thebes and because its former distribution network probably ceased to exist. From this point onwards, the local industry was reoriented to accommodate the needs of locals and incomers alike rather than dealing with export to other markets; the city took its place as one among many peripheral regional workshops, whose typical forms and motives were comparable almost everywhere in the eastern Mediterranean – probably instigated/directed by the Venetian patrons. As a city with a strong ceramic tradition, Chalcis adapted quickly to the new socio-economic demands and stylistic trends of the period. This is particularly evident in the case of the bowls bearing sgraffito decoration with concentric circles (Fig. 2.d, g). In addition to the ones made in Chalcis, similar vessels were manufactured in many places, from Constantinople and northern Greece to Asia Minor, the Peloponnese and even north Italy.Footnote 32 It is also evident in a number of other sgraffito bowls bearing geometric designs or bird motifs (Fig. 2.c), which present similarities to products of Constantinople, Thessaloniki, Cyprus and even southern Italy.Footnote 33

Apart from these higher value vessels (sgraffito or painted, imported or locally manufactured), we also detected ceramics with simpler or no decoration, whose local production has been proved or seems very probable. Here we include open and closed vessels of various shapes and functions (tableware, cooking, serving, storage, transport vessels and other utilitarian objects, including candlesticks and even moneyboxes), which could be plain glazed, partially glazed (Fig. 2.f), with simple painted decoration or unglazed.Footnote 34

As far as amphorae are concerned, although the evidence for their use from the fourteenh century onwards remains unclear, it is assumed that Chalcis both exported local or regional products, such as wine, honey and grain, and acted as a warehouse for the storage, distribution and transshipment of various commodities traded between the eastern Mediterranean and Italy.Footnote 35 Furthermore, our evidence, coming from all parts of the city, including the recent excavation of the Bailo House (Fig. 1.29),Footnote 36 shows an interesting and uniform pattern of ceramic use: imports of various origins co-exist next to wares of traditional Byzantine style, with the latter found in notably larger quantities. We may assume, therefore, that all ethnic groups residing in the city (Greeks, Westerners and Jews) used more or less the same ceramics, choosing them for a wide range of values and aesthetic reasons.

Pottery may thus serve as a starting point for the further explorations of social and economic – but not ethnic – differences within the urban population. The substantial range of products available to local consumers (local or imported, high-quality decorated wares and plainer items of various qualities) is a sign of intensified industrial and commercial activity and may point to the emergence of an advanced and diversified market, where the multiple qualities reflect respective values, consumer and economic capacities and, perhaps, clients from different social backgrounds. In fact, this situation can be compared to contemporary changes in the economic/commercial conditions of the Italian city-state markets.Footnote 37 Building upon archival information regarding the mixed identity of this population,Footnote 38 we can now distinguish their tastes and habits through the study of pottery.

1470–1687

The Ottoman conquest of the city in 1470 (Fig. 9) was a major milestone, bringing about a violent disruption of civic life and the extermination of the old and the arrival of new population. Eğriboz, as the city now came to be known, was henceforth integrated into the Ottoman system. The Venetian siege of 1687 became another landmark in the civic history of Chalcis, since we can trace (before and after) distinct socio-economic conditions and agents, as in the wider eastern Mediterranean.

For the period from 1470 to 1687, in addition to isolated historical references (Chalcis as center of the Eğriboz sanjak and the winter quarters of the Ottoman fleet), we can rely on Evliya Çelebi (ca. 1668), who presented a fairly accurate account of the cityscape;Footnote 39 he was followed by Wheler, who visited the city a few years later.Footnote 40 Their accounts are supported by the study of still-standing monuments (such as the Emir Zade Mosque, the water supply systemFootnote 41) and those that are now gone (the Suleiman I gateFootnote 42, a stone bridge over the Euripos channelFootnote 43). The archaeological record offers a mixed picture: many areas were restructured (the present-day Ayia Varvara Square, Fig. 1.38, and the eastern part of Kotsou Street, Fig. 1.32)Footnote 44, while in others pre-existing buildings were simply reused (the Bailo House and the Dominican basilica, turned into Fatih Mosque, Fig. 1.23).

This picture can be further elucidated when examined against the ceramic material: during this phase, we discern a number of imports, both from within and (perhaps surprisingly) outside the empire. These include the predominant Ottoman productions from Iznik, with specimens from all known sub-types (with blue-and-white or polychrome decoration), whose chronologies span from the late fifteenth century to approximately 1700. Western imported tableware come from well-known centres of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries in central and north Italy, including marbled ware from Pisa, Renaissance Sgraffito from Venice, and various types of maiolica, such as Early Renaissance Maiolica (stile severo), Polychrome Maiolica and Maiolica Berettina (Fig. 4) from several centres, including Venice, Faenza and Ligurian workshops.Footnote 45 These imports prove that Chalcis actively participated in the wider commercial networks and that it continued to trade with the eastern and western Mediterranean world, as well as that elite members of local society continued to be able to access quality foreign products.

Fig. 4. Maiolica berettina, 17th century. Source: Archive of the Ephorate of Antiquities of Euboea. Photo: the authors.

Although archaeometric evidence is limited,Footnote 46 local ceramic manufacture seems to have remained a constant factor in the regional economy, with higher value products (tableware), whose quality could be comparable to the imported ones, complementing the lower value objects destined to cover everyday needs. The local tableware presents the general features of the so-called Post-Byzantine pottery in their shapes, techniques, surface treatments and decorative patterns – incised or painted, abstract motifs were freely applied in the available space on both open and closed forms, under a lead glaze.Footnote 47 A particularly large quantity of such tableware was excavated in cesspits at the Sultana Negrin plot on Kotsou Street (Fig. 1.32), perhaps pointing to a commercial use of this building. These ceramics, along with a variety of plain glazed and unglazed closed vessels, have similarities in all workshops throughout the Balkans, proving a unifying interregional trend within the wider Ottoman market. Noteworthy is the close similarity of some sgraffito bowls found in Chalcis with finds from AthensFootnote 48, which may indicate a more distinctive regional pattern.

Furthermore, two interesting aspects of daily life were detected for the first time through recent pottery finds: the first is linked to the large number of night pots. These were excavated in various parts of the Ottoman city, obviously reflecting an established – yet little known – practice. The second one is represented by a sixteenth-century bowl inscribed in Hebrew and intended to hold kosher cheese (Fig. 5).Footnote 49 It reveals both the eating habits of its Jewish owners and the identity of the house where it was kept. The specific excavation (known as the Sultana Negrin plot), lying next to the nineteenth-century synagogue (which probably replaced an earlier similar structure), helped identify one of the Jewish neighbourhoods mentioned by Evliya. Situated along the main artery of the city and leading towards the city market, the exceptional wealth of uncovered finds confirms the financial importance and role of the minority communities within the civic landscape.

Fig. 5. Bowl with Hebrew inscription, 16th century. Source: Archive of the Ephorate of Antiquities of Euboea. Photo: the authors.

At the other end of the town, the Bailo House, on the basis both of its location across the main city mosque (the modern Ayia Paraskevi) and of its excavation finds, has been confirmed as an official residence (Fig. 1.23, 29): the wide range of ceramic finds – basically tableware of all provenance and types – affirms the prosperity and status of its inhabitants. This has been corroborated by a hoard of pharmaceutical implements (mortars, weights and bowls), perhaps belonging to a physician in the service of the building's owner.Footnote 50

Therefore, despite the lack of written sources, we can envisage a provincial capital with a diverse population, ethnically, professionally and economically. Its highly stratified society, with the Ottoman officials at the top, had easy access to products of various qualities and origins, both local and imported, regional and international. Connections with Italy, the Balkans and Asia Minor underscore the city's participation in long-distance trade and the importance of its port. At the same time, ceramics similar to those found in nearby Athens prove the presence of a regional network, reflecting the close ties the city retained to its immediate hinterland. This image of prosperity affirms Chalcis as a flourishing peripheral centre of the empire at the peak of its power.

It is only through this prism that we can comprehend the otherwise peculiar fact that Chalcis was the only city that successfully resisted the armies of the Holy League in 1688 and their prolonged, full-scale siege. Defenders relied upon a complex fortification pattern, including the newly erected fortress on the hill of Karababa, and were aided by the resolution of the local population. The scale and intensity of that siege, which became a milestone in the city's history, were for the first time discovered in the archaeological record, in the excavation of the Bailo House complex, which was partially destroyed and subsequently abandoned as a result of its bombing by enemy ships. Some of the cannonballs from the siege were later reused, while others were left in situ.Footnote 51

Eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries

This period, ending with the Greek War of Independence, is usually described as extremely eventful and turbulent for the Aegean and the eastern Mediterranean.Footnote 52 Our understanding of the urban and social cityscape of Chalcis in the period following the Venetian siege of 1688 has started to emerge slowly from the study of material culture (such as the Islamic tombstones);Footnote 53 the (usually negative) reports of Western travellers (such as William Martin Leake, 1805);Footnote 54 the standing monuments (such as the clock tower, known as the Seirina, Fig. 1. 36),Footnote 55 or those that have disappeared (such as a series of mosques and mansions that marked the neighbourhoods, both within the city and in the suburbs). The city had a mixed, yet segregated, population, with local elites of the island residing within the walls (only two of their mansions are still partially preserved, while many more are known from accounts and photos, Fig. 1.28, 29). Economic activities (industrial and commercial) were transferred to the suburbs outside the dilapidating walls (Fig. 1.22), where there was also space for the larger mansions of Turkish officials (out of which only a single luxurious private bath and fountain are still preserved).

The social conditions of late Ottoman Chalcis can be better understood through the study of the ceramic material, found in numerous excavations. For tableware, there is a large variety of western imports, both in terms of origin and decorative style, demonstrating the degree of domination western products enjoyed in the Ottoman East. These included notable examples coming from north Italian workshops, such as Tâches Noires from Albisola, Polychrome Maiolica from Pesaro and cheap versions of maiolica (White Maiolica and Mezzamaiolica with painted decoration in blue).Footnote 56 There are also Ottoman wares, such as marbled ware of various stylesFootnote 57 and Çanakkale Ware,Footnote 58 as well as lower quality monochrome glazed pottery for use by commoners. The presence of Kütahya cups can be directly related to the consumption of coffee, which went together with that of tobacco.Footnote 59 Of several hundreds smoking pipes, most date to the eighteenth century and were made of various qualities of clay, with meerschaum used for the better quality examples.Footnote 60 In this spectrum of finds, Chalcis seems to have been more on the receiving end of products distributed by wider commercial networks active in the Aegean. Local production does not seem to have had a notable presence or identifiable contribution (‘signature’); perhaps it was reserved only for common objects with little commercial value.

Coffee consumption and smoking have been recognized as important indicators of social status for provincial elites, used ceremonially in social gatherings and visits. The array of good-quality imported wares of various origins, along with those for serving coffee and tobacco use, were invested with notions of social standing and superiority within a provincial setting.Footnote 61 As status symbols they would have been used primarily by the residents of the civic mansions mentioned above: families like the famous Ağribozlu, who sought titles and positions in the provincial administration and maintained a network of connections with the capital and the major centres of the empire; local magnates (ayans), who managed to secure large land properties and exercised effective control on local affairs at the expense of the central authority; the heads of the Christian and Jewish communities, etc. The same habits were obviously followed by the other groups in the local society (administrators, military officers, artisans, merchants, shopkeepers), to which we may assign similar objects of poorer quality.

In fact, the variety observed in the pottery categories and their qualities reflect not only the habits but the social and economic distinctions and the human topography of Chalcis, as well as links between the local community and other Ottoman lands. This image concurs with and supports the epigraphic and architectural evidence, reaffirming the integration of Chalcis within the Ottoman peripheral system of government. During all the political upheavals of this period, the city remained unequivocally attached to and followed the Ottoman apparatus. Its allegiance was finally tested during the War of Independence (1821–28); it was the only city that the rebel forces failed to occupy.

Nineteenth to early twentieth centuries

After 1833, when the city was handed unscathed to the newly founded Greek Kingdom, Chalcis (now reverting to its ancient name Chalkis, Chalkida) lost parts of its previous (Muslim) population and in turn received (Christian) newcomers. Because of its proximity to the new capital, Athens, it soon became one of the principal harbours. The centre of socio-economic activity gradually but inexorably moved outside the walled nucleus. The urban topography and architecture were steadily influenced by the prevailing neoclassical style. The process of modernization was accelerated by the industrialization the city experienced at the end of the nineteenth century. It was finally confirmed by the demolition of the medieval walls in the first decades of the twentieth century, making way for large boulevards (the modern Eleutherios Venizelos Street: Fig. 1.1) and numerous public buildings; this, however, caused the downgrading of the old intra muros neighbourhoods to working class areas, since they were close to the harbour and the industrial zone and could henceforth accommodate various agro-industrial activities.

The diversity of this period is clearly reflected in the ceramic material. Imports include a few examples of better quality industrial products from northern Europe, manufactured in massive quantities and shipped to world markets, including the eastern Mediterranean. Porcelain tableware was mainly decorated with the transfer printed technique, as seen on plates manufactured by Spode in England. Next to them, one finds a variety of stoneware bottles for beer or wine (Fig. 6) that were transported from France or Germany to cater for a distinguished clientele.Footnote 62

Fig. 6. Stoneware bottle, 19th century. Source: Archive of the Ephorate of Antiquities of Euboea. Photo: the authors.

On the other hand, larger imports included low-value tableware from known production centres of the period, which were circulating, in large quantities, in all the territories around the Aegean and were destined for common use. These included objects from Grottaglie in southern Italy and from Çanakkale and Didymoteikon in the north Aegean.Footnote 63 Next to them, local and regional ceramic workshops remained important for covering everyday needs and domestic activities. They produced a variety of forms, such as storage vessels,Footnote 64 chaffing dishes (known in early modern Greece as ‘foufou’), glazed cooking pots and basins with simple, slip-painted decoration (Fig. 7).Footnote 65

Fig. 7. Basin with slip-painted decoration, 19th–first half of 20th century. Source: Archive of the Ephorate of Antiquities of Euboea. Photo: the authors.

Nevertheless, the existence of the Lelantine clay resources played a leading role in the area's development into an industrial hub: any building activity in the kingdom during this active economic period required the use of bricks as the basic construction unit. The massive production of bricks and tiles in the Chalcis workshops gave an unprecedented boost to ceramic manufacturing and remains today an important facet of the local economy. Many recovered specimens bear the marks and names of their producers, or simply the name of the city (Fig. 8).Footnote 66 Despite this wealth of information, which could probably be augmented with archival research, brick manufacturing in Chalcis has unfortunately been little researched.

Fig. 8. Chalcis bricks. Collection and Photo: Nikos Liaros.

Based on our material, we can discern a socially differentiated population, with a small provincial elite deriving wealth from economic-industrial activities; they shared cosmopolitan aspirations and were oriented towards European-style products. Additionally, there was a population that could afford imported wares of lower (yet adequate) quality, perhaps an emerging class of merchants, entrepreneurs, clerks and public servants. These coexisted with the workers and craftsmen that manned the various factories, whose needs would have been covered by cheap local products. Based on the distribution and percentage of the various wares, we would suggest that despite the pro-European ideology of the state and its upper class, the majority adhered to a more ‘traditional’ lifestyle. It is interesting to note that behind the neoclassical facades, most middle- and lower-class houses followed the interior arrangements of the Ottoman period, as observed in the case of the Bailo House.

Concluding remarks

From the ninth to the twentieth century, Chalcis has been a witness to the ever-changing political and socio-economic conditions that shaped the Aegean world and created its historical and cultural identity. The city, despite being an important peripheral centre, has not received the attention it deserves by modern researchers. The reason for this oversight may be because academic studies on more recent periods have tended to focus mainly on historical sources, largely neglecting the archaeological record (Fig. 9). Yet, in the case of Chalcis, material culture (in our case, pottery) can act as a primary tool for differentiating periods and tracing changes, as well as pointing out continuities and revealing consistently recurring socio-economic activities.

Fig. 9. The death of Paolo Erizzo, last Bailo of Chalcis, 1470. Fr. Zanotto, Pinacoteca dell'Academia venetta delle belle arti, 1835, Karakostas Collection. Source: Archive of the Ephorate of Antiquities of Euboea.

More specifically, the impressive continuity of pottery production can be seen as a decisive instrumentum studiorum, through which we can approach the features and habits of the local population. In terms of the manufacturing process, Chalcis succeeded in being a substantial player in the regional markets, a role the town retains to this day. When socio-economic and political conditions were favourable, this production attained an exceptional peak – a fact that may seem inexplicable to the outside onlooker. We may suppose that, quite like the majority of modern Greeks who simply ignore the fact that most bricks used in modern constructions are produced in Chalcis, the same was true for the pottery used by the Byzantines of the twelfth century, or even by the Ottomans of the sixteenth century. In a similar way, Chalcis has fallen beneath the notice of researchers, simply because the impact of its ceramic production and the socio-economic conditions behind it have rarely been given the attention they deserved.

Nikos D. Kontogiannis is an assistant professor of Byzantine archaeology and history of art, Koç University, Istanbul. His interests lie in the fields of military and domestic architecture, ceramics and minor objects, urban landscapes, industrial production and commercial networks in the eastern Mediterranean.

Stefania S. Skartsis is Head of the Department of Large-Scale Works, Hellenic Ministry of Culture. She has worked in various areas of Greece and her interests lie in the fields of Byzantine archaeology, ceramics, and commercial networks in the eastern Mediterranean.