Introduction

Urbanism entails a complex interweaving of both earlier and novel social processes and institutions that impact public and quotidian life. Mesoamerica provides an especially rich variety of approaches to urbanism, and one of its larger cultural regions, Oaxaca, encapsulates this diversity in both data and interpretations (Flannery & Marcus Reference Flannery and Marcus2015; Joyce Reference Joyce2010). Around 500 bce, Monte Albán emerged as an urban centre on a Valley of Oaxaca hilltop (Fig. 1) and developed into the powerful Zapotec state that for a millennium had no comparable urban peers in its expansive valley. Urbanism appears fundamentally different to the northwest in the Mixteca Alta, a mountainous region with less capacious valleys, each with multiple, smaller co-existing cities marked by great architectural heterogeneity. The social construction of early urban centres exhibits a fundamental characteristic: specialized processes that integrated both the city's diverse internal population as well as external communities by developing a shared social identity (Hutson Reference Hutson2016; Smith Reference Smith2014). The creation of an urban identity, however, encompassed a variety of inclusive and restrictive practices, often centred on the emergence of social differentiation and elites (Joyce Reference Joyce2010). I explore one such complex practice, feasting, and particularly its associated displays of exotic paraphernalia and associated entanglements, during the Yucuita phase (500–300 bce) at the Mixteca Alta site of Etlatongo. Due to expansive temporal and spatial coverage, I employ only that one local ceramic phase, instead referencing the following Mesoamerican periods: Early Formative (EF, 1800–1000 bce), Middle Formative (MF, 1000–300 bce), Late/Terminal Formative (L/TF, 300 bce–ce 300), Classic (CL, ce 300–800), Epiclassic (EP, ce 800–1000) and Postclassic (PC, ce 1000–1520). A recent discovery at Etlatongo contributes to further understanding the extent of distant engagements in Oaxaca as well as the Mezcala civilization of Guerrero, how Etlatongoans may have perceived an imaginary of the West, and the entanglements its presence materialized at an early urban centre.

Figure 1. Map of central to southern Mexico, indicating regions and select sites mentioned in the text.

Distant lands, entanglements and imaginaries

The display of exotic items and prestige goods plays important roles in the emergence and transformation of complex societies, as such objects materialize differential access to networks of relationships beyond those of most members of society. Due to their raw material and what has been called ‘skilled crafting’ (Helms Reference Helms1993), these objects evoke multiple entanglements with distant lands, people, networks and cosmological forces. In some cases deployed as ritual paraphernalia, the complex and distant relationships indexed by these objects imbue their users with esoteric knowledge and may accumulate social and political value (Blomster Reference Blomster2004; Brzezinski et al. Reference Brzezinski, Joyce and Barber2017). Depending on time and place, different kinds of objects serve as prestige goods. In her exploration of ancient Panamanian chiefdoms, Helms (Reference Helms1979) concludes that small golden objects, exchanged between elites, expressed sacrality due to the material's scarcity and the specialized crafting the objects required. Such things showed a leader's familiarity with distant lands and mystical realms—manifesting a repository of esoteric knowledge (Reference Helms1979, 139–40). These charged objects, as metaphors for sacredness and power, merit special attention as archaeologists increasingly explore the crucial roles of elite and non-elite ritual and religion in social negotiations and political transformations (Joyce & Barber Reference Joyce and Barber2015). I understand ritual as the performance of sequences of formal acts which invoke something beyond the quotidian; ritual is situated at ‘one end of a continuum of repetitive, structured activities, the other end of which is individual habit’ (Gazin-Schwartz Reference Gazin-Schwartz2001, 275).

Special objects evoke distant places in two different metaphysical dimensions: a horizontal one involving geographic distance and a vertical one associated with something beyond the terrestrial, often entwined with different cosmological planes. For Helms (Reference Helms1993, 176–8), the kinds of outside centres associated with these different axes channel distinct kinds of power and different potentials in terms of things’ acquisition and crafting. While boundaries between these categories blur and exhibit much variety, both naturally endowed things and skilfully crafted goods can channel originative or ancestral power, with the former more anonymous or autochthonous and the latter more personalized. The quality of inalienability accorded to skilfully crafted distant things is part of their value: ‘These goods not only encapsulate the powers and qualities of the strange and beautiful in their tangible form but also are believed to provide a direct link with the extraordinary power of their distant places of creative origins’ (Helms Reference Helms1993, 198). Indeed, the group acquiring distant things may have to modify and transform them in order to deploy exotica in local socio-political relations and rituals.

The way Helms attends to both natural and crafted aspects of objects and the different kinds of forces they evoke overlaps with aspects of relational ontologies. Critiques of Western-Cartesian notions of static objects and the shifting focus to relational ontologies throughout the indigenous Americas have produced a burgeoning literature (see Brzezinski et al. Reference Brzezinski, Joyce and Barber2017; Joyce & Barber Reference Joyce and Barber2015; Viveiros de Castro Reference Viveiros de Castro2004; Zedeño Reference Zedeño2009). Rather than simply reflecting social relationships, objects may also mediate and transform them. Through their raw material and/or their transformation by crafting, things can be both animate and agentive, with the ability to engage with other animate beings, including humans, in a reciprocal world (Joyce Reference Joyce, Kosiba, Janusek and Cummins2020; Zedeño Reference Zedeño2009). Animacy and the complementary properties and relational capabilities of objects and their combinations (Zedeño Reference Zedeño2009, 410) add another layer of entanglements that actively enable and constrain social life (Hodder Reference Hodder2012).

A discovery dating to the later portion of the L/TF from the Oaxaca coast serves as a touchstone for this paper. At Cerro de la Virgen in the lower Río Verde Valley, a broken stone mask and other objects were offered together in what has been interpreted as a sacred, agentive bundle (Brzezinski et al. Reference Brzezinski, Joyce and Barber2017). The mask exhibits rain-god imagery in a style and material foreign to the coast, perhaps manufactured in the Oaxaca highlands and acquired through exchange networks. In addition to its aesthetic qualities and non-local material, the bundle's value lay in its materialization of knowledge of distant lands and the associated entanglements with humans and other-than-human entities. The mask bundle acted as an ‘index object’, in the sense of a natural or modified thing or assemblage that can enhance human agency and alter the properties of other objects, agents, or places with which it is associated (Brzezinski et al. Reference Brzezinski, Joyce and Barber2017, 520; Zedeño Reference Zedeño2009, 412). Animate things vary in their potential as index objects. Some inherently animate Mesoamerican objects, based on properties and origins, include human bodies and blood, breath, marine shells and greenstone/jadeite, the latter of which also exhibits generative forces (Ardren Reference Ardren2015, 17; Joyce Reference Joyce, Kosiba, Janusek and Cummins2020, 332). The Cerro de la Virgen bundle, as an index object, was involved in founding the community due to its location under a prominent public building, which it ensouled. Its restricted location evinces differential status required to access its ritual capacities (Brzezinski et al. Reference Brzezinski, Joyce and Barber2017, 520). The entanglements of humans and their other-than-human counterparts play critical roles in the dynamics of complex societies. Joyce and Barber (Reference Joyce and Barber2015) contrast religion's role in constraining political centralization in the lower Río Verde region with its fostering of the more centralized polity of Monte Albán in the Valley of Oaxaca.

I argue that the entanglements between humans and their other-than-human counterparts reflected in exotic objects also reference projections of the nature of distant places, evoking different imaginaries. Social scientists employ ‘imaginary’ or ‘social imaginary’ in myriad ways, perhaps most famously as imagined communities (Anderson Reference Anderson1983), which extend beyond the boundaries of face-to-face interaction to such shared communities as ‘nation’, connected by collective knowledge. As a broader rubric than either ideas or practices, anthropologists explore social imaginaries of real people, with positionality impacting one's perception of social surroundings instead of a fixed concept shared by a bounded group (Strauss Reference Strauss2006, 323; Taylor Reference Taylor2002, 92). A process of dialogue and interaction informs social imaginaries, marked by competing discourses and contingent change, with multiple and simultaneous social imaginaries (Anderson Reference Anderson1983; Ardren Reference Ardren2015). I adapt the concept and refer to it simply as ‘imaginary’ to investigate how people conceive of more distant places and people. Imaginary usefully suggests a type of cognition beyond the knowledge of perceptible facts, especially relevant in comprehending the distant based on scattered material evidence, oral narratives, cultural beliefs, and what Strauss (Reference Strauss2006, 339) calls ‘fantasized knowledge’. The concept of imaginary embraces the flexibility and different perspectives of people along a continuum of status in MF Etlatongo, some of whom had more entanglement with distant places, people and things.

Mimesis and alterity frame iterations of imaginaries of distant places and how local communities emulated, modified and incorporated exotic objects. Mimetic representations emulate aspects of an original form, sometimes in a different medium, as the goal is to evoke the original's potency. At the same time, alterity encompasses otherness, both its quality and people's imaginary of the other, a cognitive filling-in of projections about distant people, places and things (Taussig Reference Taussig1993). Because people may know little of the other in contrast to the self and the home, stereotypes and normative views more commonly inform alterity (Lau Reference Lau2013, 9). The concepts of mimesis and alterity intertwine in their work. At Chaco Canyon in the American Southwest, Mesoamerican connections have been postulated due to the appearance of chocolate-based beverages served in a new form: cylindrical vessels (Crown Reference Crown2018). Interpreted as an example of mimesis, the cylinders appear to be hybrids, incorporating a new form into local crafting traditions and designs, with what is perceived as alterity (the exotic beverage) contained in a vessel evincing a familiar style (Crown Reference Crown2018, 401). Internalizing some special essence or power from the exotic also features in Lau's (Reference Lau2013) exploration of alterity in the Andes, where a rich artistic corpus displays how groups (the Moche and Recuay) in adjacent regions imagined and visualized each other, while also distinguishing ceramic assemblages among various Recuay groups. Lau (Reference Lau2013, 22) concludes that alterity, in recognizing and inscribing something vital from the other, framed local identity and made Recuay persons.

Display, commensalism and interaction at Etlatongo

Feasting provides one arena for the display and deployment of things from distant places. A ritual activity focused on commensal consumption and hospitality, feasting occurs in a suprahousehold setting and is polysemic (Dietler Reference Dietler and Insoll2011, 180). Centred on food, drink, and gifts mediated through tropes of hospitality, feasts establish relationships of reciprocal obligations and status differences, affording a venue for representing and manipulating social relations. Feasts manifest the hosts’ local alliances and external connections, with access to distant landscapes, knowledge, and supernatural experiences as sources of power materialized through the social agency of foreign objects (Dietler Reference Dietler1990). Indeed, commensal hospitality may form and reinforce crucial relationships between exchange partners, providing a setting for transferring materials (Dietler Reference Dietler and Insoll2011).

Feasting activities exhibit great diversity in foods consumed, underlying motivations, and potential outcomes, fostering integration or furthering social differentiation. Feasts have been implicated in substantial social transformations (Dietler Reference Dietler1990; Hayden Reference Hayden2014). Commensal hospitality, especially the sharing of food, fosters at least the appearance of integration and solidarity, providing a sense of community while disguising and promoting differential status and authority. Feasts rarely represent discrete binaries of either reinforcing social boundaries or promoting integration and community; they perform various roles simultaneously and fall along a continuum (Dietler Reference Dietler and Insoll2011). Of the general modes of ‘commensal politics’ feasts explored by Dietler (Reference Dietler and Insoll2011, 185), diacritical feasts feature symbolic marking of social distinctions, indicated by ostentatious but rare objects or food. Such feasts generate and reinforce social stratification and have been linked with elite strategies in the formation of urban societies in the Mixteca Alta. At Etlatongo's L/TF neighbour Cerro Jazmín, feasting was a recurrent, political positioning tactic for the city's elites and rulers, exhibiting several forms through time (Pérez Rodríguez et al. Reference Pérez Rodríguez, Martínez Tuñon, Stiver Walsh, Pérez Roldán and Torres Estévez2017, 116). Initially, diacritical feasts, small in terms of participants, were deployed to promote and establish elites; hosts displayed imported Valley of Oaxaca ceramics and rare foods that required a certain degree of learning to prepare and consume. Over time, the focus shifted to more inclusive feasts, which relied on local Mixtec pottery and foods to foster a more communal ethos (Pérez Rodríguez et al. Reference Pérez Rodríguez, Martínez Tuñon, Stiver Walsh, Pérez Roldán and Torres Estévez2017).

The presence and display of exotic objects have deep roots at Etlatongo. During the EF, Etlatongo imported ceramics from the early Gulf Olmec centre of San Lorenzo (Blomster et al. Reference Blomster, Neff and Glascock2005), some of which exhibit symbolically charged motifs, interpreted as abstract versions of cosmological forces (Cyphers Reference Cyphers2012). Beyond the few actual imports, Etlatongo potters also crafted numerous mimetic emulations and reimaginings of these vessels and symbols. Some Etlatongoans also engaged with Olmec-style tropes of embodiment and aesthetics, materialized in distinct white-slipped figurines. Etlatongo artisans integrated some alien corporeal elements, such as head shape, into local figurines, creating hybrid imagery and stylistic juxtapositions (Blomster Reference Blomster2004). The myriad imported and locally produced materials at Etlatongo, displaying exotic aesthetics and complex iconography, suggest an Olmec imaginary with which at least some Etlatongo residents were deeply entangled and engaged. Based on their positionality, Etlatongoans would have had different understandings and projections of this imaginary. Such objects, from Olmec-style serving vessels to ballplayer figurines, would have exhibited what Helms (Reference Helms1993) refers to as more personalized ancestral power. Previously, I have invoked the concept of a superordinate centre, an earthly approximation of a divine, cosmological model, to characterize how the EF Olmec may have been imagined at Etlatongo, as the relationship of a superordinate centre with outside regions depends on distance and the interest of the participants in this interaction (Blomster Reference Blomster2010).

In contrast, while many Mesoamerican groups in the subsequent MF adopted and adapted Olmec-style imagery as elements of local political and economic strategies, regionalization characterized Etlatongo and most of Oaxaca. Rather than the elaborate iconography related to alliances and exchange networks evinced in monumental sculpture at MF central Mexican highland sites such as Chalcatzingo (cf. Grove Reference Grove1987), Oaxacan sites exhibit only very abstract imagery, the so-called ‘double line break’ on ceramics, indicative of limited engagement in larger pan-Mesoamerican visual trends. At the end of the MF, Etlatongo exhibited nascent urbanism, manifested by settlement extending to a nearby hilltop, monumental platforms and changes in political economy (Blomster Reference Blomster2004). The Yucuita phase and the first centuries of the L/TF, corresponding with the founding and growth of Monte Albán, exhibited more pronounced interactions between Oaxacan regions. Examples of greyware pottery, excavated in the Mixteca and coastal Oaxaca, have been sourced to the Valley of Oaxaca, while Mixtecs crafted and exported fine brownware pottery (Joyce et al. Reference Joyce, Neff, Thieme, Winter, Elam and Workinger2006). A newly discovered Yucuita-phase commensal context at Etlatongo manifests these Oaxaca alliances but also the Mixtec hosts’ association with something fundamentally different and previously unreported in Oaxaca: a Mezcala-style greenstone sculpture. This discovery complicates interpretations of MF to L/TF interaction and urbanism as Mixtec urban elites exhibited more knowable and personalized Oaxacan connections in mimetic forms as well as originative, cosmogonic forces, materialized in an object accentuating alterity.

Discovery of the Etlatongo figure

Located in the Nochixtlán Valley near the confluence of two rivers, Etlatongo has been most recently explored by the Formative Etlatongo Project (FEP) from 2015 to 2017. While the FEP focused on exploring EF socio-political complexity, it also documented substantial Yucuita phase occupations. Excavations at Mound 1-1 in the southern portion of the site (Fig. 2) discovered two superimposed EF ballcourts (Blomster & Salazar Chávez Reference Blomster and Salazar Chávez2020). This charged public space hosted subsequent MF burials and other activities, such as those documented in its southeast portion where excavations encountered a shallow, roughly oval-shaped pit (referred to here as Feature 1), 1.20 m long and 0.60 m deep from top to bottom (Fig. 3). Feature 1's earthen walls exhibited burning, and numerous charred materials (chunks of earth, large sherds and fire-cracked rocks) filled its upper matrix and partially sealed its entrance. Large ceramic sherds comprised nearly 70 per cent (n = 1760, weighing over 37,000 g) of Feature 1's matrix (B1418) immediately below the burned materials. In contrast, the only lithic artefact recovered from B1418 was a complete greenstone figure. Lithics, generally in the form of debitage, are ubiquitous in all Etlatongo contexts that produce frequent ceramic artefacts; the absence of debitage in B1418 accentuates its unusual nature. Ceramics decreased in frequency below B1418 while charcoal and ash increased with vertical depth. All ceramics stylistically pertain to the Yucuita phase, and charcoal recovered from just under B1418 dates to the latter half of this phase, 2294±24 bp (AA-112041: 405–236 bc at 95.4 per cent; date modelled in OxCal v.4.2, using IntCal13 calibration curve: Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2017; Reimer et al. Reference Reimer2013). Based on associated pottery, the range can be further refined to 405–300 bce.

Figure 2. Etlatongo, Feature 1 (shown by star). (a) Aerial view showing Mound 1-1; dashed line indicates limit of EF occupation (base image Google Earth); (b) Operation B on Mound 1-1; (c) plan view of Operation B units (in grey).

Figure 3. Feature 1: detail, showing discovery of the greenstone figure (top); completed excavation (bottom).

While the ceramic assemblage from this feature remains under analysis for a thesis, preliminary results indicate that of the at least 79 vessels present (either largely reconstructible or represented by large sherds), many are fancy serving vessels in terms of pastes, unusual forms, surfaces and decorations (Breault et al. Reference Breault, Blomster, Pierce and Glascock2021). The assemblage emphasizes greywares, with rare and exotic forms known from contemporaneous Monte Albán, such as a large ‘fishplate’, as well as vessels with a pedestal base, enhancing their display and functionality as serving vessels (Fig. 4). Compositional analysis indicates some Feature 1 greywares originated in the Valley of Oaxaca (Breault et al. Reference Breault, Blomster, Pierce and Glascock2021). All ceramics in this assemblage encompass either Zapotec or local Mixtec aesthetic tropes, although the context lacks fine brownware bowls (fancy Mixtec serving vessels, frequently decorated), that usually occur in Yucuita phase contexts at Etlatongo.

Figure 4. Greyware composite silhouette bowl on pedestal base from Feature 1.

The quality of the ceramics, their high frequency within a relatively small area, the numerous burned materials and the virtual absence of lithics illuminate the special nature of the activity represented by this deposit: refuse from a single feasting episode. The thick concentration of carbonized material at the base of this shallow pit may represent some of the associated cooking, although food remains themselves were scarce, apparently deposited elsewhere. The ceramic vessels, some of which evince probable food remains adhering to their interiors, were placed in the pit at the feast's conclusion. Based on the large chunks of burned materials in Feature 1's upper matrix, additional burning terminated this event and, combined with burial of the ceramics, helped to seal this feature.

In a feasting context that materialized distant connections, the coup de grace is a Mezcala-style greenstone anthropomorphic figure (Fig. 3). Remarkably undamaged and discovered nearly upright to slightly leaning, this figure (referred to here as the ‘Etlatongo figure’) appeared in the upper portion of B1418, inserted on top of the discarded vessels before they were buried. Its placement, perforating the pile of ceramics beneath it, probably signalled this commensal activity's cessation. The inclusion of such a rare and exotic item in a context that, based on the ceramics, probably engaged a relatively small number of people suggests a particular type of commensal event: a diacritical feast, with a focus on exclusivity (see above). The hosts reserved this foreign object's deposition for the culmination of the interment of the feast's material remains, with the Etlatongo figure's head probably visible as ash, soil, and other debris filled the pit around it. The Etlatongo figure evoked entanglements with distant lands and imaginaries, in this case aesthetically and geographically much farther to the west of Oaxaca.

Guerrero and the Mezcala style

Like Oaxaca, modern state boundaries define Guerrero as a cultural region within ancient Mesoamerica, obscuring the diverse environments and rich tapestry of cultures these states contain. Often subsumed as part of ‘West Mexico’ (the states of Colima, Jalisco, Michoacán and Nayarit), a unique cultural region somewhat divergent from Mesoamerica, Guerrero has increasingly been seen as more integrated with Mesoamerica, especially Central Mexico and Oaxaca (Reyna Robles Reference Reyna Robles2006). As on example of its diverse landscapes and cultures, a survey of Teotihuacan-related materials in Guerrero divides the state into five regions (Nielson et al. 2019). Archaeologists have long conceptualized Guerrero as a crucial region through which trade routes and raw materials passed, connecting coastal and highland Oaxacan communities with other parts of Mesoamerica, especially through the movement of West Mexican obsidian.

Named after the Mezcala River, a term used for the Upper Balsas’ eastern course, Mezcala refers to a specific sculptural style, an archaeological culture region, and a larger geographic area. Reyna Robles (Reference Reyna Robles2006, 27) defines the Mezcala archaeological culture, manifested in distinct architectural and ceramic styles as well as portable stone sculpture, as extending south and especially north of the Mezcala River throughout central and northern Guerrero, crossing just over the borders into the states of Morelos and Mexico. After examining private collections of sculptures in this region for decades, Covarrubias (Reference Covarrubias1948) defined Mezcala as the one ‘purely local’ sculptural tradition of the five he identified for this region, contrasting it with others that more closely resembled Olmec and Teotihuacan styles. Lacking contextual information, Covarrubias (Reference Covarrubias1957) illustrated a variety of Mezcala stone sculptures, including anthropomorphic and zoomorphic figures, masks, as well as temple models. Covarrubias (Reference Covarrubias1948, 88) proposed three anthropomorphic types, two of which (Chontal and Sultepec) he defined based on greater detail in facial features compared with his more abstract, schematic and subtly modelled Mezcala type (Fig. 5), often referred to as Type 2 or Type B (González & Olmedo Vera Reference González and Olmedo Vera1990; Paradis Reference Paradis1991). Microscopic analysis indicates shared technology across these disparate objects, suggesting Covarrubias’ three types are probably varieties of one greater Mezcala style (Melgar Tísoc & Solís Ciriaco Reference Melgar Tísoc and Solís Ciriaco2006). The lack of a substantial excavated sample from Guerrero complicates efforts to seriate them chronologically or to devise more complex and nuanced classifications for Mezcala sculptures (González & Olmedo Vera Reference González and Olmedo Vera1990, 17–25), thus Covarrubias’ three ‘types’ retain some utility.

Figure 5. Mezcala sculptures from Guerrero, not to scale. (a) Covarrubias’ Type 2, published without context or scale (redrawn from Covarrubias Reference Covarrubias1957, fig. 46); (b) excavated at La Organera-Xochipala, no scale (redrawn from Reyna Robles Reference Reyna Robles2006, fig. 79); (c) excavated at Ahuináhuac, 65 mm high (redrawn from Reyna Robles Reference Reyna Robles2006, fig. 80).

Mezcala sculptures’ temporal placement within Guerrero remained hypothetical, usually extending from early CL to PC (González & Olmedo Vera Reference González and Olmedo Vera1990, 40). The 1989–90 research at Ahuináhuac, located just north of the Mezcala River, finally associated stratigraphically excavated Mezcala sculptures with carbon samples (Paradis Reference Paradis1991). Of the seven examples, the most typically Mezcala Type 2 figure (Fig. 5c), just over 7 cm high, exhibits shallow grooves for the eyes and mouth. Interpreted as offerings deposited as part of the reconfiguration of architectural space, Paradis (Reference Paradis1991, 64–6) revised the uncorrected range of 700–230 bce to the first half of the L/TF, based on ceramics excavated with the Ahuináhuac figures as well as two later carbon dates associated with similar ceramics from La Trinchera to the north. The Etlatongo figure supports the earlier part of Paradis’ date range, from the late MF (400–300 bce; see above). While a few Mezcala sculptures date to the Classic period (González & Olmedo Vera Reference González and Olmedo Vera1990, 30), excavated sculptures elsewhere in Guerrero primarily date to the EP, based on both associated materials and radiocarbon dates at the urban centre of La Organera-Xochipala, where one context featured figures offered in a ballcourt (Reyna Robles Reference Reyna Robles2006, table 20). From these limited contextual data, one potential pattern emerges: Mezcala sculptures served as offerings associated with architectural elements or, at San Miguel Ixtapan (in Mexico state), as mortuary offerings within a temple (Reyna Robles Reference Reyna Robles2006, 182). After the EP florescence of the Mezcala region, the local production of Mezcala sculptures appears to end along with the abandonment of the urban centres.

Covarrubias’ (Reference Covarrubias1948) elucidation of Mezcala-style anthropomorphic stone sculptures remains prescient. Ranging in colour from dark brown/black to light green/blue-green, the stone itself is most parsimoniously referred to under the generic rubric ‘greenstone’, as few examples have been subjected to mineralogical or compositional analyses, although serpentine and andesite appear to be favoured materials. The general green colour of the stone has been linked throughout Mesoamerica with vital essence, regenerative forces, transformative powers and fertility deities (Ardren Reference Ardren2015; Taube Reference Taube2015), an association reinforced by their later use as offerings in the Aztecs’ Templo Mayor (see below). As noted above, greenstone objects serve as index objects throughout Mesoamerica. Size varies; while a large (150+) sample abandoned by looters in 1946 measures between 150 and 300 mm in height (Reyna Robles Reference Reyna Robles2006, 62), those found archaeologically in Guerrero are usually at the low end of this range, or smaller. In their abstractness, Mezcala figures contrast aesthetically with most Mesoamerican sculptural canons. Figures classified as Covarrubias’ Type 2 usually conform in overall elliptical shape to a petaloid axe, sometimes with evidence of use on either or both ends (Gay Reference Gay1967). Stylized and schematic, Mezcala sculptures consist of a series of flat to slightly rounded planes, generally organized symmetrically, separated into several zones by deep grooves or cut marks. Torsos exhibit little anatomical detail, with facial features and extremities cursorily indicated. Figures stand, sit, or squat, with arms either extending parallel to the torso, demarcated by a groove, or folded over the chest; legs are separated either by a groove between them or a vertical cut.

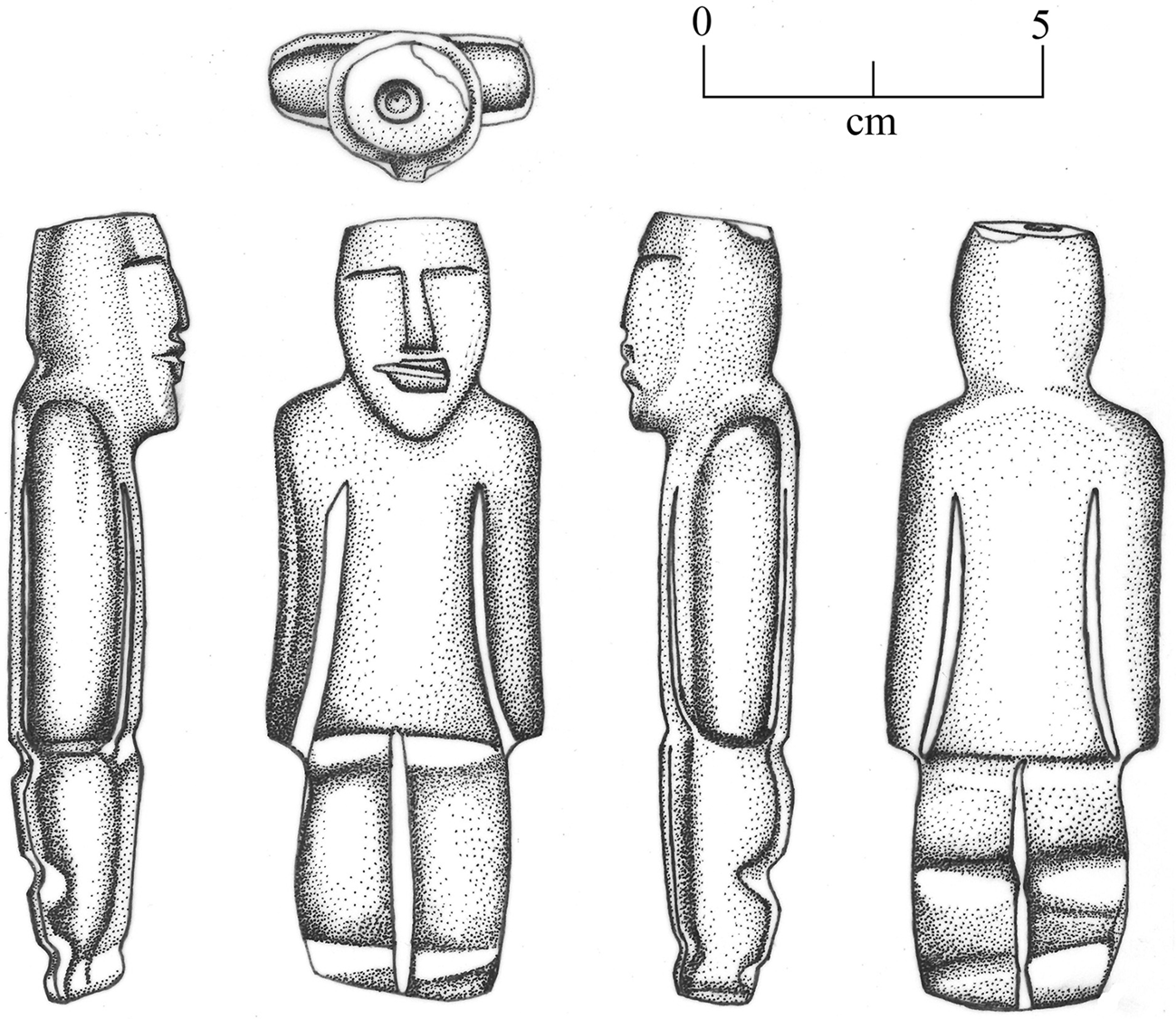

The Etlatongo figure as Mezcala style

Measuring 115 mm in height and weighing 146.6 g, the Etlatongo figure's surface colour ranges from dark green to black (Fig. 6). The generally lustrous surface on closer inspection appears waxy and slightly porous, with grains easily visible; the figure's hardness lies between Mohs scale 3.5 and 4. Due to texture, porosity and hardness, the metamorphic stone has been identified as serpentinite (Moecher pers. comm., 2019), found in Mexico's central and southern highlands, such as Guerrero, and spreading across its border with Oaxaca (Jaime-Riverón Reference Jaime-Riverón2003, 189).

Figure 6. Etlatongo greenstone figure.

The Etlatongo figure displays characteristics primarily of Covarrubias’ Type 2. Potentially derived from an axe, although neither end exhibits use, the rounded bottom precludes this object from standing on its own, despite its upright posture. In profile, it forms a flat plane, broken only by the projecting head (Fig. 7). Abstract features of the human form, indicated by minimal, subtle anatomical elements, contrast with a well-shaped head. Similar to many Mezcala sculptures, the figure lacks primary or secondary sexual characteristics. The long, narrow torso, which flares out slightly in the pelvic region almost like a garment, consists of broad, well-burnished flat planes with a limited curvilinear aspect, especially in the transition to the figure's sides. Pronounced vertical grooves delimit the slender arms, without hands, while a deeper, less regular vertical groove separates the legs. A shallow groove splits the legs from the torso, with additional grooves above the figure's base suggesting feet. Grooves demarcating limbs on the figure's back side mirror those on the front. The greatest sculptural relief occurs on the back of the legs, where curving, projecting thighs and calves contrast with deep horizontal grooves. The head comes to a rounded point at its chin. The forehead and nose form one plane, which interrupts the shallow groove indicating eyes. Two irregular lips project from the lower face, forming a slightly open mouth. On top of the flat head, a small, shallow hole extends 5 mm into its centre, perhaps allowing the object to be suspended, or for the placement of a small removable headdress.

Figure 7. Etlatongo figure, with view of hole on top of its head.

The artist juxtaposed surface textures. The coarse nature of the grooves enhances the smooth, lustrous planes of the figure's torso and limbs. The head especially emphasizes these contrasting textures (Fig. 8). The forehead, sides and back of the head are smooth and lustrous, achieved through fine horizontal polishing, contrasting with coarse, vertical streaks below the eyes. I argue these textural differences are not simply the result of the surface with which the artist worked, as one of the hardest areas to access, the short neck, is extremely lustrous. The contrasting textures, and the overall abstract nature of the piece, emphasize its alterity, demarcating it from contemporaneous Zapotec and Mixtec aesthetic tropes.

Figure 8. Detail of the Etlatongo figure's head, showing different textures and finishing.

Mezcala sculpture beyond Guerrero

More Mezcala sculptures have been excavated beyond than within Guerrero. Three central highland sites remain most frequently associated with Mezcala sculptures: Teotihuacan, Xochicalco and the Templo Mayor, at the heart of the Aztecs’ capital, Tenochtitlan.

Teotihuacan's entanglements with other L/TF and CL Mesoamerican civilizations remain debated (Cowgill Reference Cowgill2015). Several ‘ethnic enclaves’ flourished at Teotihuacan, including a Zapotec barrio, and bone isotopes indicate the presence in apartment compound N1W5:19 of a small group of West Mexican people who spent at least some time in Michoacán (Begun Reference Begun2013). While carved stones or stelae with ‘Teotihuacan imperial iconography’ have been reported in Guerrero (Nielsen et al. Reference Nielsen, Jiménez García, Rivera, Englehardt and Carrasco2019), there is minimal evidence of an impactful Teotihuacan physical presence (Reyna Robles Reference Reyna Robles2006). At Teotihuacan, Mezcala-style sculptures appear in several contexts, such as the Feathered Serpent Pyramid (Cowgill Reference Cowgill2015, fig. 7.15), where sculptures in a variety of styles emerged in only a few graves, concentrated in offerings of sacrificed individuals (Sugiyama Reference Sugiyama2005, 148). Mezcala sculptures’ abstract quality distinguishes them from the local and well-developed Teotihuacan stone sculpture genre, although with some overlap in features suggestive of interplay between artisans and aesthetics from these regions. While Guerrero probably provided raw materials, such as serpentine and slate, used in Teotihuacan lapidary production, it remains unclear how many Mezcala sculptures arrived as finished products. Analysis of technological style at the multi-ethnic Teopancazco complex indicates that most Mezcala-style figures exhibit standardized Teotihuacan lapidary production techniques associated with artisans who specialized in greenstone and certain slate objects (López Juárez & Murakami Reference López Juárez, Murakami and Manzanilla2018, 483).

After Teotihuacan's collapse, EP Xochicalco flourished and manifested a complex mosaic of long-distance trading networks with various Mesoamerica civilizations, including the Zapotecs, Mixtecs and Mayas. Except for frequent West Mexican Ucareo obsidian (Hirth Reference Hirth2000), material from the west, especially Guerrero, is scarce. Several sculptures reported as Mezcala style from the site's upper ceremonial zone (Noguera Reference Noguera1961, fig. 5) appear more similar to Teotihuacan or local Xochicalco aesthetics, suggesting minimal, if any, Mezcala imports.

At the Templo Mayor, the late PC Aztecs validated their imperial programme by offering objects that expressed their dominion over time and space, including those representing their central Mexican ancestors: Teotihuacan, Xochicalco and the early PC Toltecs (Matos Moctezuma Reference Matos Moctezuma1988). They included Mezcala-style sculptures in at least 14 offerings, primarily those dating to ce 1454 and especially ce 1469, marking their empire's massive expansion and wider interactions with distant realms, such as Guerrero (López Austin & López Luján Reference López Austin and López Luján2009). Archaeologists excavated 382 examples of Mezcala-related objects, 220 complete figures and 162 masks and/or heads, manifested in various greenstones foreign to the Basin of Mexico, including serpentine, serpentinite, phyllite and schist (Melgar Tísoc Reference Melgar Tísoc, Wiesheu and Guzzy2012, 183). González González (Reference González González and Boone1987, 149) calculates that 80 per cent appear to be pure Mezcala style, including examples of all three of Covarrubias’ types, with the remainder mostly representing a mixture of Mezcala and Teotihuacan traits, which are consistently flatter, less abstract and with headdresses. Based on a combination of raw materials and formal elements, González and Olmedo Vera (Reference González and Olmedo Vera1990) classify the complete figures into 27 groups, some of which do not have examples known from Guerrero.

While the sculptures’ placement in the Templo Mayor reflects Aztec rather than Mezcala concepts and aesthetics, several patterns emerge. Mezcala figures usually occur in groups; the largest concentration, 98 complete figures and 56 masks, occurs in a stone offering box on the Tlaloc side of the dual temple and, similar to the Etlatongo example, they generally stood upright, or leaned against each other (López Austin & López Luján Reference López Austin and López Luján2009). The Mezcala figures also display a consistent association with water and abundance, often paired with images of Aztec fertility deities, and sometimes placed with thousands of shells (especially conch) and greenstone beads. Similarly to other Mesoamerican groups for whom greenstone objects have been interpreted as index objects, the Aztecs associated greenstone beads with supernatural energy, regeneration and fecundity; their focus on mostly greenstone Mezcala sculptures reinforces that association (González González Reference González González and Boone1987). In addition to offering some Mezcala sculptures alongside images of Tlaloc and other fertility deities, the Aztecs further emphasized this connection by painting many Mezcala sculptures with rain, maize and earth deity attributes; some also had aquatic and underworld-related glyphs or symbols painted onto their backs (López Austin & López Luján Reference López Austin and López Luján2009, 337). I suggest that painting these objects may have animated them in way that resonated with the Aztecs, who recognized their alterity and sought to harness their exotic energy for imperial ritual and political agendas. Additionally, perhaps the mimetic elements added by the Aztecs translated these abstract Mezcala figures into the more naturalistic style of Aztec art. In addition to re-using and modifying earlier Mesoamerican art, the Aztecs created their own versions for use in various contexts and purposes (Umberger Reference Umberger1987, 99).

The Mezcala objects, usually interpreted as produced prior to the construction or expansions of the Templo Mayor, may represent tribute, extracted from earlier Guerrero sites, ranging from the CL to PC (González & Olmedo Vera Reference González and Olmedo Vera1990; López Austin & López Luján Reference López Austin and López Luján2009). Recent analyses of their technical style indicate much of the Tenochtitlan Mezcala corpus may have been made at Aztec palace workshops that produced objects specifically for the Templo Mayor (Velázquez Castro & Melgar Tísoc Reference Velázquez Castro and Melgar Tísoc2014).

Etlatongo, Oaxaca and the West

Oaxaca's archaeological record evinces limited contact with Guerrero, accentuating the visual alterity of the Etlatongo figure. While long recognized by archaeologists as a potential source of raw materials, such as metamorphic greenstones, Guerrero has not been invoked as a supplier of crafted objects for highland Oaxacan civilizations. The material evidence for how Etlatongoans perceived a Western imaginary (conceived of here as areas/peoples west and south of the Nochixtlán Valley, including Guerrero as well as other peoples and places from ‘West Mexico’) remains limited.

Interaction primarily manifests as obsidian from a West Mexico source, Ucareo (Michoacán), which travelled through Guerrero, including the EF to MF coastal site La Zanja, part of an important Pacific Coast trade route which linked coastal Guerrero to central Mexico and the Valley of Oaxaca (Ebert et al. Reference Ebert, Dennison, Hirth, McClure and Kennett2015, 68). Ucareo obsidian constitutes a substantial amount (32–38 per cent) of the sourced samples from several EF Valley of Oaxaca sites, but contributes only 6 per cent of EF Etlatongo's large sourced sample, suggesting Mixtec participation in alternate EF exchange networks (Blomster & Glascock Reference Blomster and Glascock2011). An important exception to the EF association of the West with only raw materials in Oaxaca comes from the coastal site of La Consentida, where Tlacuache phase pottery has been interpreted as evincing West Mexican stylistic affiliations, with motifs similar to Capacha-phase pottery of Colima (Hepp Reference Hepp2019). The La Consentida pottery, however, is as much as 400–500 years earlier than Colima's Capacha phase, raising issues of origins and communication. While La Consentida could be part of an early coastal West Mexican trade route, none of its obsidian has been sourced as from Ucareo (Hepp Reference Hepp2019).

Throughout MF and L/TF highland Oaxaca, reliance on Ucareo obsidian decreased, diminishing at MF Etlatongo, disappearing altogether at L/TF Cerro Jazmín, and forming only a minor presence at Monte Albán (Feinman et al. Reference Feinman2018, table 1). Monte Albán's high L/TF and CL frequency of central Mexican obsidian from sources (Pachuca and Otumba) controlled by Teotihuacan supports the idea of a special relationship between those two cities (Feinman et al. Reference Feinman2018). Other contemporaneous Valley of Oaxaca sites exhibited low frequencies of Pachuca obsidian, instead accessing sources rare or absent at Monte Albán and participating in different exchange networks, emphasizing the city's limited economic control over the valley. Communities participated in exchange networks distinct from those of Monte Albán; obsidian frequencies reflect complex political and economic considerations rather than using the closest source or one doled out to them by that urban centre (Blomster & Glascock Reference Blomster and Glascock2011; Feinman et al. Reference Feinman2018).

In contrast, sites in the lower Río Verde Valley first deployed Ucareo obsidian in the early L/TF, where its utilization remained robust throughout the prehispanic era (Brzezinski Reference Brzezinski2019). During the L/TF and early CL, coastal sites also exhibited higher frequencies of Pachuca obsidian than have been documented at Monte Albán (Joyce Reference Joyce2010), indicating both this region's unique interactions with Teotihuacan and its importance in exchange routes. The lower Verde provides another rare example of potential movement of finished goods from the West in the form of several L/TF ceramics (Joyce Reference Joyce1991). Although the ceramics’ origin and movement to coastal Oaxaca remains unclear, L/TF people in this region had a very different imaginary of the West, perhaps involving specific exchange partners, than those in other parts of Oaxaca.

The lack of engagement and mimesis with Guerrero aesthetics, specifically those of Mezcala, is reinforced by portable stone sculpture at Monte Albán, which exhibits local artistic tropes and, in approximately 50 L/TF and CL greenstone figures, Teotihuacan stylistic elements (Caso Reference Caso, Wauchope and Willey1965; Winter Reference Winter and Rattray1998). Zapotec-style greenstone sculptures, also found northwest of Monte Albán in a L/TF offering box at San José Mogote (Flannery & Marcus Reference Flannery and Marcus2015, 259–66), display more naturalistic features, such as clearly defined, fleshy limbs, than either Teotihuacan or Mezcala imagery. Indeed, the only remotely Mezcala-like sculptures from Monte Albán come from a late CL tomb, where several small (50–60 mm) figures display extremely abstract torsos and heads, which Caso (Reference Caso, Wauchope and Willey1965, 905) contrasts as representing a ‘cruder’ technological style compared with typical Zapotec lapidary work. These small sculptures may represent the start of the later PC Mixtec penate tradition of miniature human figures, which Caso (Reference Caso, Wauchope and Willey1965, 908) defines as miniature human figures carved in a standing or seated position in a prismatic or cuboid form. While penates have been compared in form and size with the contemporaneous camahuiles tradition of southern Guatemala, L/TF examples have been found archaeologically of the latter, which in contrast to Mezcala figures, generally have flat backs (Love Reference Love, Guernsey, Clark and Arroyo2010, 171).

Discussion

Etlatongo elites signalled to a small group of commensals their entanglements with Valley of Oaxaca Zapotecs and more distant realms as part of a diacritical feasting event. Local Mixtec vessels mingled with Zapotec-style greywares, some of which came from the Valley of Oaxaca. As feasts often serve as contexts to celebrate and articulate regional exchange systems (Dietler Reference Dietler and Insoll2011, 182), the display of vessels materializing these connections may have been part of the rationale for this particular feast, which featured one particularly exotic object: the Etlatongo figure.

I interpret this figure, inserted vertically and penetrating several layers of spent ceramics like a staff, or its frequent referent in Mesoamerican cosmology, a world tree, as an index object. Greenstone is in a class of Mesoamerican index objects that have animating properties, with MF offerings of greenstone axes, often placed vertically, referencing cosmogonic forces (Taube Reference Taube2015). Unlike those often featureless axes, the Etlatongo figure has a face, enhancing its communicative abilities and agential capacity (Brzezinski et al. Reference Brzezinski, Joyce and Barber2017). This figure was no passive thing, but in a relational taxonomy, an essential agent for transforming and animating other materials, mediating social relations and enhancing human agency (Zedeño Reference Zedeño2009). I further argue that this object, deposited intact and then buried, served as a sacrificial offering. Other examples of greenstone figures in the Valley of Oaxaca, including the L/TF sculptures from San José Mogote, have been interpreted as representing sacrificial victims (Flannery & Marcus Reference Flannery and Marcus2015, 264). I argue instead that this agentive Etlatongo object had vital energy that the hosts sacrificially offered and transferred, consecrating the space and augmenting the vitality of other beings, including themselves, which enhanced their status. Its sacrifice also memorialized this space and the activities and participants it hosted. Both its animating properties and the hosts’ role in its sacrifice may have referenced and activated the sacred covenant between humans and supernatural forces, a fundamental aspect of Mesoamerican cosmogony, with elites as mediators in this relationship well established at contemporaneous Monte Albán (Joyce & Barber Reference Joyce and Barber2015).

Index objects connect other objects and people, forming assemblages. In this sense, the Etlatongo figure is similar but distinct in its work compared with the Cerro de la Virgen stone mask and associated objects that comprised a sacred bundle, interpreted as an index object. The stone mask collaborated with the other associated objects as a divine social agent to ensoul the public building under which it was buried (Brzezinski et al. Reference Brzezinski, Joyce and Barber2017, 520). The Etlatongo figure worked with and against the other materials in its context, augmenting and animating different kinds of entanglements. The figure enhanced the distant, indexed by a variety of Zapotec-style ceramics, connecting the hosts with probable foreign partners and allies in the commensals’ eyes. Similar to how mimetic processes had inscribed some earlier Olmec-style elements into local Mixtec ceramic assemblages, creating hybrids that reflected engagement on various levels in exotic symbolic and aesthetic systems, Yucuita-phase Etlatongo potters integrated elements of Zapotec ceramics (forms, decoration and paste recipes) into their craft. Mixtecs imported and exported ceramics, and the sharing of design elements on vessels between Oaxaca regions complicates determining where they may have originated. The Etlatongo hosts and commensals probably shared a Zapotec imaginary based on intimate engagements with familiar exchange partners and possibly overlapping communities of practice of potters, a very different imaginary than that devised for the West.

This Mezcala-style figure, abstract in imagery and focused on alternating surface textures, contrasts with the other materials in this context, working against them and contemporaneous local aesthetic tropes. Its alterity defines it as something distant and other, part of an imaginary with few graphic cues. The Etlatongo figure provided a visual referent in conjuring the West, beyond an imaginary associated primarily with exotic raw materials, but one peopled by less knowable partners and agents, both human and non-human. One salient aspect of alterity is that distant others and things have some vital properties that can be alienated, reworked and transformed through physical and symbolic acquisition, enabling local agents to harness and deploy these forces (Lau Reference Lau2013, 12). Unlike the example of Chaco cylinders, which through mimesis visually appeared to be in a local style but served an exotic beverage, or the Mezcala figures from the Templo Mayor, transformed into more visually mimetic Aztec forms with the addition of painted cosmological symbols, no effort to translate and incorporate the Etlatongo figure remains evident. No hybrid figures incorporating Mezcala aesthetic tropes have been documented at contemporaneous Mixtec sites or in subsequent L/TF sculptures in highland and coastal Oaxaca. Only its association with Etlatongo-made and foreign feasting vessels provided any apparent local framing, which perhaps allowed for alienating and routing some of its regenerative forces into local projects.

The Etlatongo figure reinforced the foreign relationships and associated political affiliations indexed by Zapotec vessels and introduced more faraway and esoteric cosmological forces. As a naturally endowed substance (greenstone) that was skilfully crafted, this index object manifests aspects of Helms’ (Reference Helms1993) two metaphysical dimensions. While the display of Zapotec-style vessels in Feature 1 represented more personalized ancestral forces, with objects acquired from nearby allies as well as motifs incorporated into locally made Mixtec pottery, the Mezcala imagery invoked more anonymous cosmogonic, originative energy. Although the figure may have referenced a distant contact known to the hosts, its lack of translation and incorporation make this unlikely. This Western imaginary was less knowable but very potent and prestigious, and entanglements with it further promoted status differentiation.

The figure's origin, as well as its circulation before arriving at Etlatongo, may have been as complicated to untangle for those ancient Mixtecs who knew the most about it (probably the hosts) as it is for archaeologists. Its undamaged condition suggests limited and careful use before its deposition in Feature 1. The singularity of this image in Oaxaca supports an origin in the Mezcala region of Guerrero, from where it may have travelled through some of the same exchange networks as Ucareo obsidian, interacting with and impacting distant allies. Since Etlatongo, compared with contemporaneous Valley of Oaxaca villages, had less interaction with West Mexican obsidian networks, the Zapotecs may have had access to other, overlapping Guerrero networks that included both raw materials and finished objects. A few centuries later, lower Verde Valley communities also participated in networks through which Ucareo obsidian and exotic skilled crafts circulated, suggesting additional potential exchange partners involved in the figure's arrival at Etlatongo. The lack of comparable Mezcala sculptures elsewhere in Oaxaca introduces the possibility that the Mixtec hosts engaged with a unique network of distant allies and partners. There also appears to be general similarity with the Etlatongo figure's placement in Feature 1 with the non-domestic contexts (ranging temporally from L/TF to EP) of the few examples excavated in the Mezcala area, usually as offerings within architecture. At the Templo Mayor, the Aztecs invariably deposited Mezcala figures in offerings that indexed fecundity. Perhaps some of these concepts reflect earlier perceptions of Mezcala sculptures that adhered to the figure during its peregrinations to Etlatongo. Additional engagements at intermediate points along the way between this figure and other agents in different contexts further transformed its value, meanings and affiliations, as it accumulated biography as part of its social life (Appadurai Reference Appadurai and Appadurai1986; Kopytoff Reference Kopytoff and Appadurai1986). Each element of its trajectory from its creation to arrival at Etlatongo, involving known exchange partners, distant agents and cosmological forces, represented other prestigious entanglements and affiliations, augmenting its potency.

Conclusion

The discovery of the Mezcala-style Etlatongo figure in a context of diacritical feasting dating to 405–300 bce contributes to issues in Mesoamerican archaeology as well as broader questions regarding interaction, imaginaries, commensalism and early urban processes. First, the Etlatongo figure augments our limited knowledge of the Mezcala civilization. Probably produced in Guerrero, its late MF date from Etlatongo indicates an earlier production of Mezcala figures by several centuries than the oldest excavated Guerrero examples (Paradis Reference Paradis1991). The Etlatongo figure's context corresponds with disparate temporal and spatial data that Mezcala sculptures appear primarily in non-domestic contexts as offerings, indexing generative forces. The contextual similarity of the limited excavated assemblage of Mezcala sculptures evokes the association between the movement of exotic products and knowledge between regions (Helms Reference Helms1993).

Second, the Etlatongo figure expands our knowledge of the extent of late MF interaction in Oaxaca and the conceptualization of imaginaries. Nascent urban elites at Etlatongo signalled relationships with Oaxacan cohorts through an assortment of exotic greyware vessels during a commensal event. While these vessels probably indexed Monte Albán allies, other communities in the Valley of Oaxaca and lower Río Verde Valley engaged in interaction networks independent of that urban centre and represent additional potential Etlatongo partners. The Etlatongo hosts aspired to display even more distant connections, sacrificing a Mezcala-style greenstone figure on top of spent feasting vessels. I argue this agentive figure functioned as an index object (Zedeño Reference Zedeño2009). Exhibiting both naturally endowed material and skilled crafting, the Etlatongo figure mediated relationships between humans and non-humans with which it interacted. The Etlatongo figure materialized the entanglements through which it and other objects were constituted as valued and prestigious, its sacrifice perhaps invoking and channelling the cosmological forces that formed part of the sacred covenant (Brzezinski et al. Reference Brzezinski, Joyce and Barber2017; Joyce & Barber Reference Joyce and Barber2015). The figure's alterity remained largely unmodified. Rather than inscribing it through mimetic processes into local representational systems as with contemporaneous Oaxaca exotica, its lack of translation referenced more enigmatic but potent cosmogonic forces as part of an imaginary of the West, which in Helms’ (Reference Helms1993) terms may have been perceived as more of a primordial outside realm than a superordinate centre. Intermediate points along its journey to Etlatongo imbued the figure with additional value and transformed meanings (Kopytoff Reference Kopytoff and Appadurai1986).

Finally, the Etlatongo figure intervenes in exploring the social construction of early urban centres through suprahousehold activities. The late MF to early L/TF represents a time of fundamental transition throughout Oaxaca, where feasts have been interpreted as a strategy to establish and promote early urban elites (Pérez Rodríguez et al. Reference Pérez Rodríguez, Martínez Tuñon, Stiver Walsh, Pérez Roldán and Torres Estévez2017, 116), whose roles in animating practices and as intercessors in the sacred covenant became increasingly endorsed (Joyce Reference Joyce, Kosiba, Janusek and Cummins2020, 352). The associated feast probably occurred on Mound 1-1, its exclusivity further enhanced by restricting the number of commensals as well as viewership by non-participants below. The hosts focused on the display of exotica, perhaps a necessary initiatory element into this new status. Due to its small size and substantial competition evinced in its exotica, I argue that this feast at Etlatongo lay at the diacritical end of a commensal continuum, promoting the status of some elites in competition with their cohorts (Dietler Reference Dietler and Insoll2011). The trope of commensal hospitality along with the mediating aspect of these new statuses, however, combined exclusionary and inclusionary elements. The Etlatongo figure materialized the hosts’ intercession with numinous realms and indexed political alliances accessed by them during its acquisition (Helms Reference Helms1993), entanglements that underlay their knowledge claims and social roles. Indeed, perhaps the object's alterity played a crucial role in framing the mediation aspect of elite identity. This extraordinary figure's placement along with Zapotec and local Mixtec ceramics expressed the hosts’ efforts to balance local alliances and foreign connections, forming a dual identity that reflected the mundane and the cosmological and their ability to intercede between them (Schaeffer Reference Schaeffer, Englehardt and Carrasco2019). The emergence of this dual mediating identity also encompassed nascent elite roles in negotiating between domestic and public spheres, ultimately transforming older but still salient strategies of displaying exotic goods.

Early urban elites at Etlatongo exhibited their restricted access to distant places and unique imaginary of the West to negotiate between factions from the community, trading partners, numinous forces and foreign allies. One venue for such displays, commensalism employed multiple social dimensions beyond the political, forming part of a larger programme of engagement with the population in crafting and negotiating a shared urban social identity at Etlatongo.

Acknowledgements

The research was supported by the National Science Foundation (BCS-1156373), permits and/or support from the Consejo de Arqueología/INAH, the Centro-INAH-Oaxaca, the officials and people of San Mateo Etlatongo and a dedicated field and laboratory staff. D. López Hernández drafted Figure 7, V.E. Salazar Chávez crafted Figures 1 and 2 and S. Breault prepared Figures 4 and 6. I thank D. Carballo, A. Dent, G. Gutiérrez, G. Hepp, K. Hirth, A. Joyce, M. Miller, M. Winter and two anonymous reviewers for comments and feedback on various aspects of this paper. All errors remain my own.