Introduction

The Early Neolithic settlement cluster of Vráble is one of the largest known settlement sites with materials of the ‘Linear Pottery Culture’ (LBK) in central Europe. It is thus a suitable case study to investigate the social and political implications of early Neolithic community agglomeration processes, a phenomenon that is not very well understood (R. Hofmann et al. Reference Hofmann, Medović and Furholt2019; Petrasch Reference Petrasch, Cladders, Stäuble, Tischendorf, Wolfram, Cladders, Stäuble, Tischendorf and Wolfram2012). LBK settlements are often seen as consisting of independent farmsteads, or household economic units, that were integrated into local and regional networks, rather than forming socially and politically integrated village communities. The site of Vráble, with a minimum number of 313 houses, separated into three spatially segregated settlement parts (Fig. 1), indicates that collective forms of organization beyond the household, such as village or neighbourhood communities, or lineages and clans (as proposed by Bogaard et al. Reference Bogaard, Krause and Strien2011) might also have played an important role in structuring the social relations of this site. We thus want to explore the question of in what ways and to what extent particularist interests (e.g. those of individual households) and units of collective action (e.g. neighbourhood- or settlement-wide institutions) interrelate or compete. We see this in the wider context of contemporary Neolithic settlements in the Balkans, where different social configurations have been studied. For example, settlements connected to Vinča or comparable materials are in many cases (e.g. Crnobrnja et al. Reference Crnobrnja, Simić and Janković2009; Furholt Reference Furholt, Hofmann, Moetz and Müller2012; R. Hofmann Reference Hofmann2013; Müller et al. Reference Müller, Rassmann, Kujundzic-Vejzagic, Müller, Rassmann and Hofmann2013b; Schier & Draşovean Reference Schier and Draşovean2004) considered villages in the sense that although there might be varying degrees of household autonomy, the village community constitutes the most important social institution of a residence group. This is a concept that probably has its roots in the Near Eastern Neolithic (Düring Reference Düring2006; Furholt Reference Furholt2016; Reference Furholt, Gori and Ivanova2017). Vráble, located in the southern part of the LBK area, not too far from the Carpathian basin, might be reflecting a more Balkanic tradition of a stronger role of the overall village community at the expense of household autonomy, which might be generally stronger in most of the LBK contexts in the northern parts of central Europe.

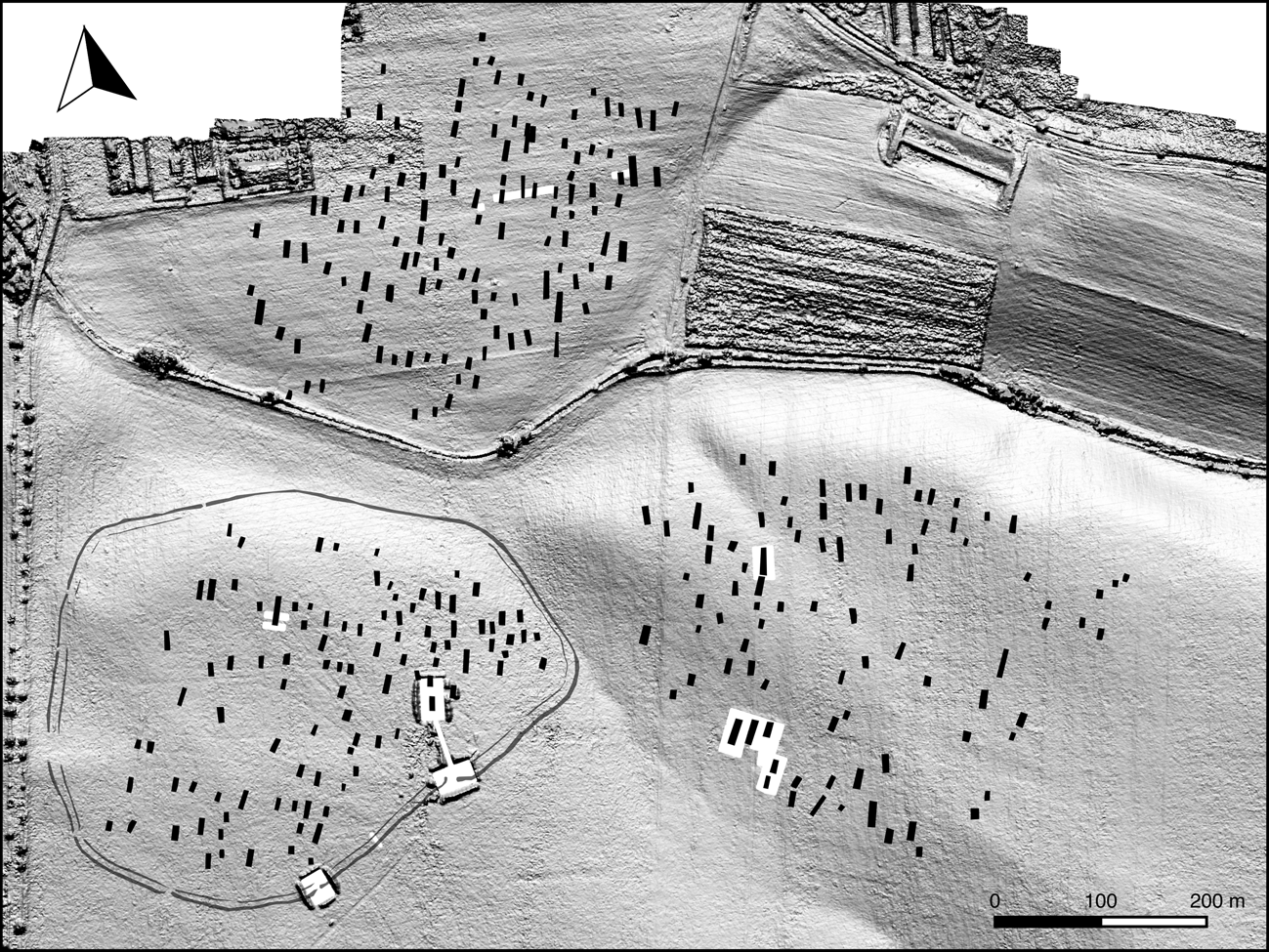

Figure 1. Reconstruction of the early Neolithic settlement site of Vráble, showing houses and the enclosure system, based on the magnetic plan, projected onto the modern landscape. The figure also shows the position of excavations in the years 2012–17 (in white).

Thus, we began our research with the hypothesis that Vráble might represent a community united by stronger village-wide institutions, and that this might be a function of its proximity to southeastern Europe, where such institutions are in general stronger than in central Europe. In this paper, we will discuss to what extent the extraordinary concentration of settlement in Vráble is connected to processes of social integration into neighbourhood and village communities, and how those social institutions relate to the social role of individual households or farmsteads. Are there overarching collective or hierarchical institutions of decision-making? What is the relation between household autonomy and village communality? We aim to characterize the dynamic relationship between these different levels of social organization over the 300 years of settlement history in Vráble, in order to understand better the social agglomeration process and subsequent abandonment of this site. This will have implications for understanding the wider phenomenon of conflict and social transformation associated with the end of the LBK phenomenon around 5000 cal. bc.

The social context

Our main research interest in the relation between household autonomy and village communality is reflected in the heated debate about the so-called ‘yard model’ that has dominated LBK research for recent decades. Although this debate has often centred around how best to date individual houses in LBK settlements, it is very much related to the question of socio-spatial organization of settlements, with different models that are connected to different ideas about the overall social structure this spatial organization represents. The ‘yard model’ states that even sites with dense house-plans such as Vráble were in reality made up of a much smaller number of autonomous, spatially isolated farmsteads. Neighbouring houses would represent different periods, as new houses were built on the same farmstead area, while the older ones were successively abandoned (Boelicke et al. Reference Boelicke, von Brandt, Lüning, Stehli and Zimmermann1988; Stehli Reference Stehli and Rulf1989; Reference Stehli, Lüning and Stehli1994; Zimmermann Reference Zimmermann, Cladders, Stäuble, Tischendorf and Wolfram2012). In this model, the farm as an independent economic unit is emphasized, as is its claim to a specific spot of land, which is, according to the model, passed down through the generations. This model is built upon a chronological system which was established in the Rhineland area and uses pottery decoration as the main chronological marker.

While the original proposition of the ‘yard model’ has been claimed as a method to determine settlement structure without prejudging its outcome (Zimmermann Reference Zimmermann, Cladders, Stäuble, Tischendorf and Wolfram2012), it has largely led to the assumption that networks of individual yards/farmsteads would have been the default configuration of LBK settlement communities. This was challenged by Oliver Rück (Reference Rück2007; Reference Rück, Cladders, Stäuble, Tischendorf and Wolfram2012), who argued for the existence of a house-row concept, that would thus display a higher degree of social integration above household level (motivating households to build their dwellings in pre-defined rows). Other scholars often try to mediate between these somewhat contradicting views (Link Reference Link, Cladders, Stäuble, Tischendorf and Wolfram2012), adding more variants (Lefranc & Denaire Reference Lefranc and Denaire2018; Lenneis Reference Lenneis, Cladders, Stäuble, Tischendorf and Wolfram2012). Alternative models stress the existence of house-groups, or neighbourhoods (Bogaard et al. Reference Bogaard, Krause and Strien2011; Czerniak Reference Czerniak, Amkreutz, Haack and Hofmann2016; Hofmann Reference Hofmann2016). It seems to be more than a coincidence that Rück's objections against the yard model were especially welcomed by colleagues working in the southern area of LBK settlements, like Hungary and Austria (Bánffy et al. Reference Bánffy, Osztás and Oross2013; Lenneis Reference Lenneis, Cladders, Stäuble, Tischendorf and Wolfram2012; Marton & Oross Reference Marton, Oross, Cladders, Stäuble, Tischendorf and Wolfram2012), because here excavation plans more often seem to indicate overall, settlement-wide patterns.

In our opinion, it is important to acknowledge the possibility of many diverse and dynamic forms of settlement organization in the vast region with LBK material culture. This is also the case with regard to the chronological and social development of a single settlement.

The archaeological evidence from Vráble

To study the dynamic relationship between different social units within the Neolithic site of Vráble (located on plots called Vel'ké Lehemby and Farské), we can draw on a near-complete settlement plan, generated on the basis of geophysical investigations (Winkelmann et al. Reference Winkelmann, Bátora, Hohle, Kalmbach, Müller-Scheeßel, Rassmann, Furholt, Cheben, Müller, Bistáková, Wunderlich and Müller-Scheeßelin press),Footnote 1 which provides house numbers, positions, sizes and orientation.Footnote 2 This allowed us to develop a different research strategy than the time- and cost-intensive large-scale excavations that hitherto have dominated LBK research. Instead, we were able to apply a more focused approach, targeting specific features of interest, according to our research questions. As we are interested in the question of whether or in what form social integration is associated with social agglomeration, we targeted 14 individual houses and house groups from different parts of the settlement in order to assess differences in subsistence strategies, traditions of material culture production and use, and access to raw materials within and between house clusters and between the three parts of the settlement (north, southeast or southwest). In addition, we excavated parts of the enclosure surrounding the southwest section of the settlement, to understand better the role of this structure for social demarcation or integration.

The magnetic plan (Fig. 1) shows that the settlement is comprised of three units of approximately the same size, shape and orientation: all three parts, each located on a slight elevation separated from one other by a creek and a depression, measure approximately 15 ha in size (except the northern part, which is however partly destroyed by modern buildings; the original shape and dimension probably corresponded to the other two parts of the site). All three parts show a trapezoidal shape (again, for the northern part we have to reckon with partial destruction in the northwest), and similar orientation with a wider section located in the northeast and a less wide one in the southwest. We interpret this as a reflection of a common mental image which seems to apply for all the settlement parts. Interestingly, the trapezoidal shape is also the most common for LBK enclosure ditches (Saile & Posselt Reference Saile and Posselt2004). In parts of the settlement, house clusters or house rows are visible, which could indicate social sub-units above household level, or reflect successive house generations, with younger houses being built beside and close to the old, abandoned ones.

Chronological differentiation

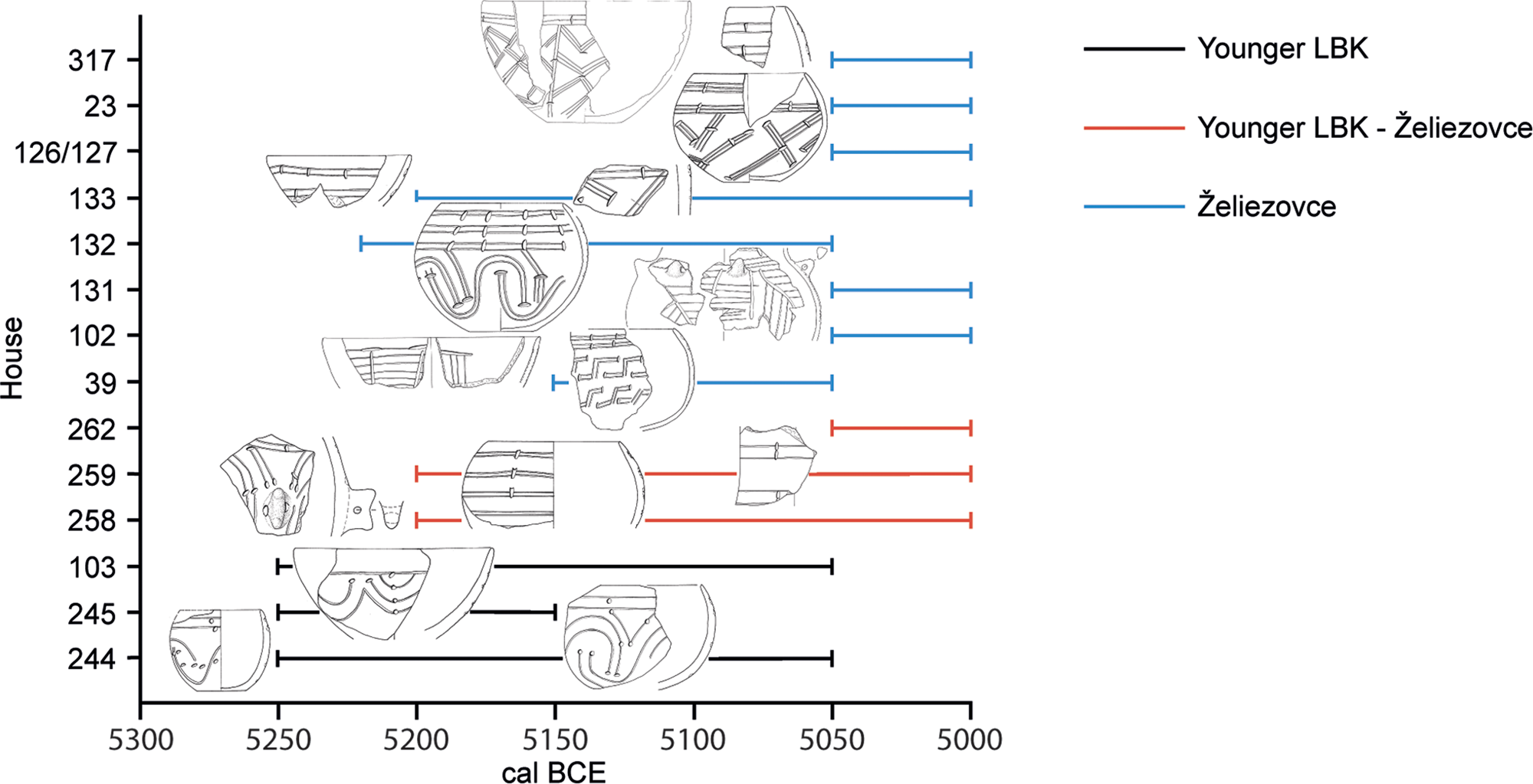

The basis for an understanding of the social organization during the lifetime of the settlement in Vráble is a chronological differentiation of the houses and the enclosure. We created a chronological model based on the results of 138 radiocarbon dates from our excavation trenches and a coring programme in the southwestern settlement area aimed at extracting datable materials from as many houses as possible (Meadows et al. Reference Meadows, Müller-Scheeßel, Cheben, Agerskov Rose and Furholt2019). We dated 14 houses in our excavation units, complemented by 9 additional houses from the coring project. While this is only a sample of the 313 houses present, it was sufficient to apply Bayesian modelling that strongly suggests that the three settlement parts do not represent a sequence of successive villages, but existed contemporaneously during most of the period from 5250 to 5000/4950 cal. bc. We may have missed early outlier houses, but we have established a robust overall chronological model, which is consistent with the expectations from pottery typochronology (Fig. 2), which lacks Older LBK material. While there is a lot of overlap between the two stylistic groups, Younger LBK and Želiezovce, a comparison of pottery material in the houses dated by Bayesian modelling of 14C dates show that Younger LBK pottery stops being deposited around 5100 bc, and that Želiezovce, while it might start to be used some time after 5200, dominates the period from 5100 bc to the end of the settlement. Prelengyel pottery is used as burial pottery around 5000 bc (Cheben et al. Reference Cheben, Bistáková, Wolthoff, Mainusch, Müller-Scheeßel, Furholt, Furholt, Cheben, Müller, Bistáková, Wunderlich and Müller-Scheeßelin press).

Figure 2. Chronological sketch of Younger LBK and Želiezovce-style pottery from Vráble illustrated on the estimated maximal house occupation periods. (Based on modelled 14C dates derived from Meadows et al. Reference Meadows, Müller-Scheeßel, Cheben, Agerskov Rose and Furholt2019, plus additions.)

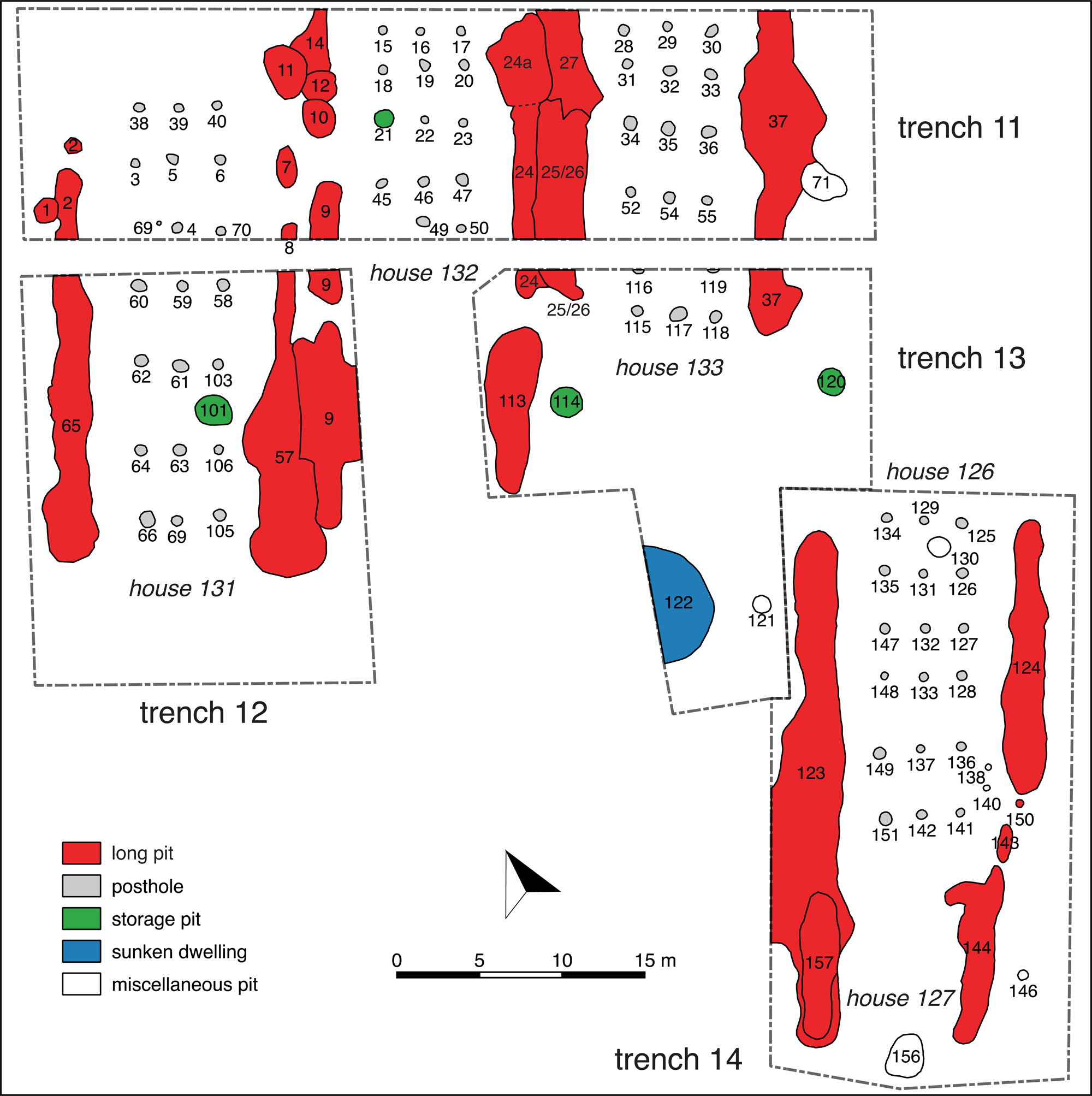

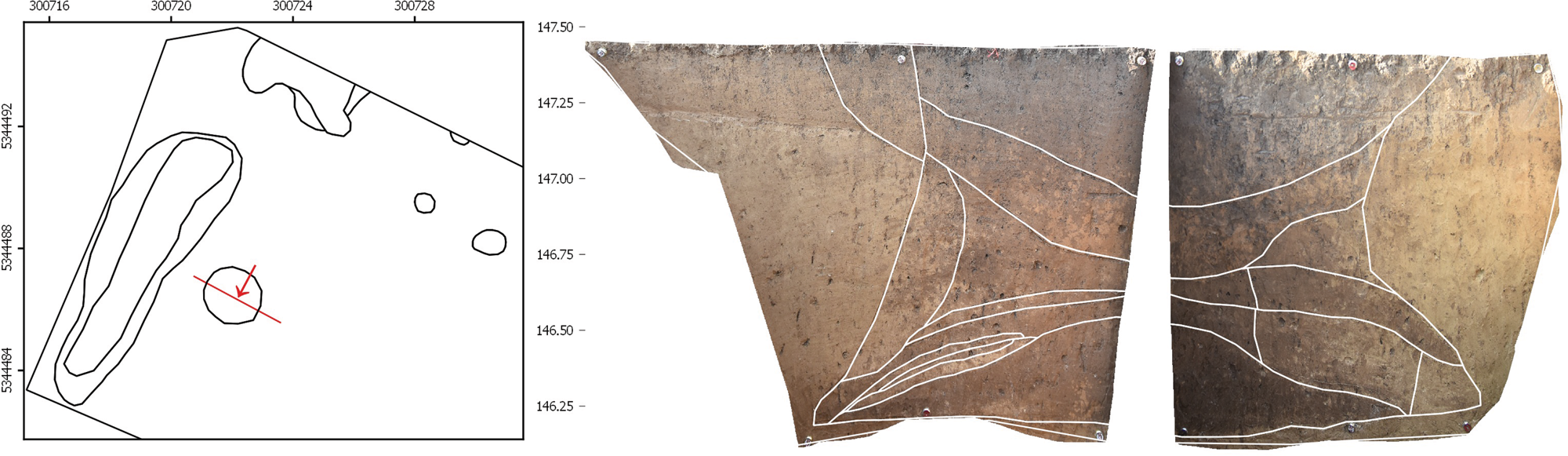

The chronology is additionally informed by our excavation results. In the 2016 campaign, we excavated a house group, consisting of five houses (Fig. 3) which were clearly clustering together, while at the same time being spatially separated from other houses (Müller-Scheeßel et al. Reference Müller-Scheeßel, Cheben, Filipović, Hukel'ová and Furholt2020a). In the 2014 campaign we excavated a row of five parallel houses, three of them standing close together. Both these house groups were chosen as they potentially represented contemporaneous social sub-units within the settlement communities, be it a household cluster (e.g. Czerniak Reference Czerniak, Amkreutz, Haack and Hofmann2016) or a row of contemporary houses. However, after the excavation and in the light of stratigraphy and 14C dates, it became clear that these houses in both groups were in fact not contemporary, but rather represented several hundreds of years of successive occupation (Müller-Scheeßel et al. Reference Müller-Scheeßel, Cheben, Filipović, Hukel'ová and Furholt2020a; Staniuk et al. Reference Staniuk, Furholt, Müller-Scheeßel, Cheben, Furholt, Cheben, Müller, Bistáková, Wunderlich and Müller-Scheeßelin press).

Figure 3. Plan of the excavation area of 2016. The house group excavated turned out to represent a sequence of non-contemporary houses, in accordance with the ‘yard model’.

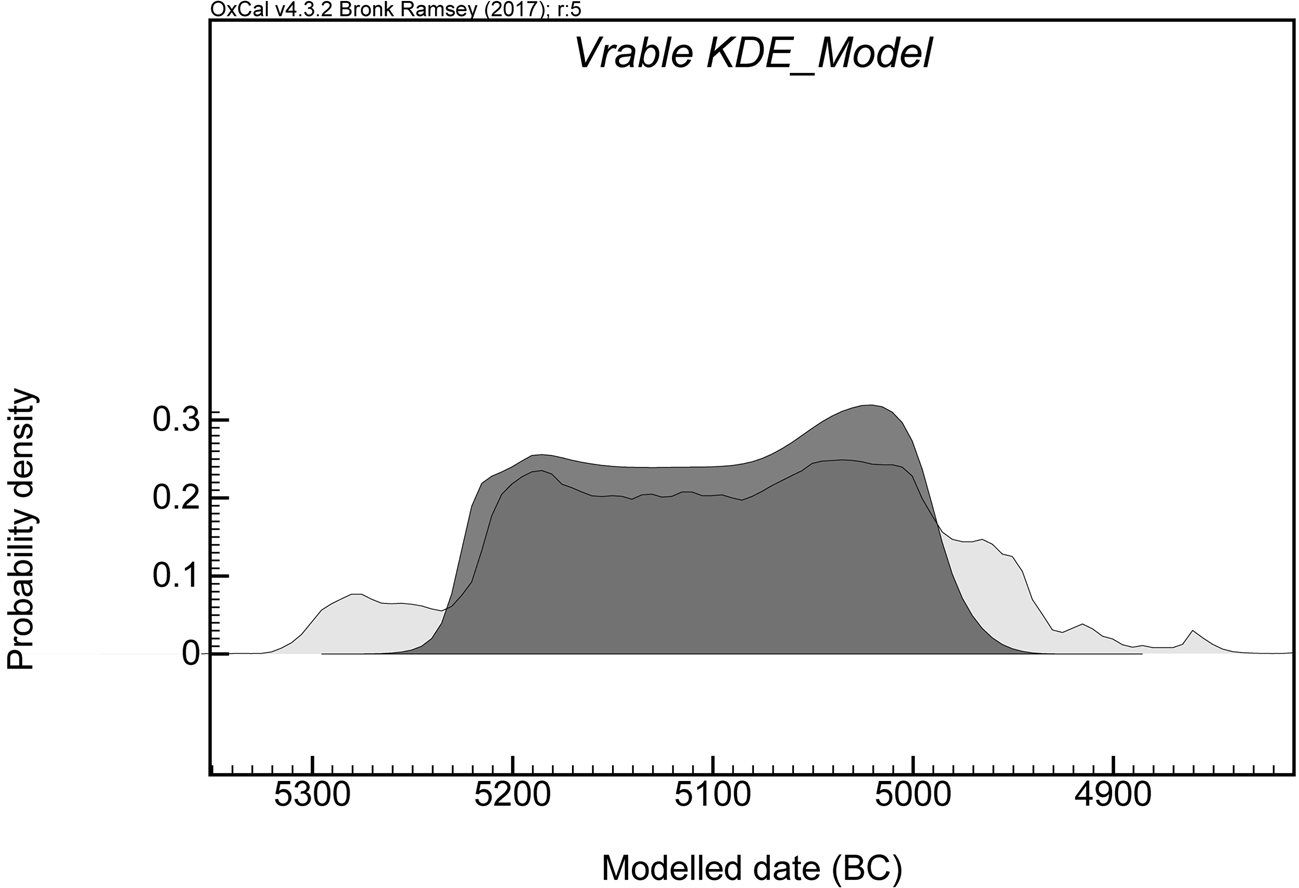

The duration of individual houses is a much-debated topic in LBK research. The modelled durations calculated for the dated Vráble houses are variable (Meadows et al. Reference Meadows, Müller-Scheeßel, Cheben, Agerskov Rose and Furholt2019). And these time-spans represent the period in which the lateral long pits were filled up, rather than the real house durations. If we assume an average house duration of 40 years, and a total time-span of 250 years for the whole settlement, an average of 50 contemporaneous houses would have been present in Vráble at any given time. This calculation could be modified by inserting shorter or longer average house durations. If we assume these 50 houses to be evenly spread out in the settled area of Vráble, each house gets an area of about 0.7 ha, which is surprisingly close to the space assumed in the classic yard model of the Rhineland area (Zimmermann Reference Zimmermann, Cladders, Stäuble, Tischendorf and Wolfram2012). From the opposite starting point, if we assume a yard size of 0.5 ha, the built area in Vráble would have had space for a maximum of 68 yards. This seems consistent with an average number of 50, assuming some dynamics in the settlement development. Indeed, as shown in Figure 4, assuming that the Kernel Density Estimation (KDE) of the house-related 14C dates represents settlement activities, it seems that there is a an increase in activities in the later period 5100–5000 bc, after which the curve shows a rapid decline, leading to abandonment around 4950 bc. We can even go one step further, as we found a significant correlation between house orientations, which vary between a northeastern and northern direction, and the 14C-dated age of a house. Müller-Scheeßel et al. (Reference Müller-Scheeßel, Müller and Cheben2020b) explain this finding with the neurological phenomenon of ‘pseudoneglect’, which causes a systematic deviation towards the left, whenever humans try to reproduce a specific direction, for example through comparison with an already existing house. If we use house orientation as a basis for chronological differentiation, and compare the distances of nearest neighbours of any given time (that is of houses with similar orientation), we find two clear mean values, of about 70 and 150 metres (Müller-Scheeßel et al. Reference Müller-Scheeßel, Müller and Cheben2020b), which indicates that there is a standard space allocated to each house, which is about 0.5 ha, and thus close to the space calculated above, using a different approach. The difference (between 0.7 and 0.5 ha) is explained by the fact that the first calculations assumed a constant number of houses at any given time, which is unrealistic. From the orientation of houses, as well as from the 14C dates, it seems far more likely that Vráble started with a smaller number of houses, slowly grew until it peaked around 5100 bc, and that the building density decreased towards the end of the settlement.

Figure 4. A chronological model of Vráble, derived from Meadows et al. (Reference Meadows, Müller-Scheeßel, Cheben, Agerskov Rose and Furholt2019), plus additions. The KDE of all available 14C dates indicates a slow increase of activities until 5050, the time when the enclosure was erected.

These calculations come with large uncertainties, where average house durations, average numbers of coexisting houses and yard sizes are mutually related. Moreover, as the dating of houses relies on the material from the lateral long pits, the taphonomy of their filling process is crucial (Květina Reference Květina2010; Stäuble Reference Stäuble and Lüning1997) and could skew our dating results for each individual house by up to a generation.

However, when it comes to our main question about the internal social organization of the site, we can at least conclude that the chronological models of Vráble, as well as the excavation results in single houses and house clusters/house rows, unanimously point towards a settlement structure which is made up of individual, spatially isolated farmsteads, with one or two contemporary houses, instead of house groups, or contemporary rows of houses. This is a pattern that corresponds well with the yard model, as discussed above. While other sites have shown conclusive evidence for contemporary house clusters (Czerniak Reference Czerniak, Amkreutz, Haack and Hofmann2016), and compelling cases have been made for house rows (Bánffy & Oross Reference Bánffy, Oross, Gronenborn and Petrasch2010; Jakucs et al. Reference Jakucs, Bánffy and Oross2016), in the case of Vráble, individual farmsteads seem to dominate the picture. House clusters or rows of houses visible in the settlement plan represent sequences, intergenerational continuity of farmsteads, within spatially relatively autonomous yards. This implies a marked autonomy of households.

Characterizing farmsteads

The six farmsteads we have excavated—we count here both the house-groups and the individual houses at different places on the site—show distinct differences in their access to raw materials, interregional contacts, subsistence strategies and material culture styles. As is not uncommon in southwest Slovakian LBK sites, stone tools are generally infrequent, most excavation trenches yielding 5–15 chipped stone tools. Yet in the 2016 excavation trenches we found 267 chipped stone artefacts, 105 of which were obsidian, including one blade core, and two core rejuvenation pieces (Müller-Scheeßel et al. Reference Müller-Scheeßel, Cheben, Filipović, Hukel'ová and Furholt2020a). In all the other trenches combined we had found eight pieces of obsidian. The closest source for obsidian is the eastern Slovakian Carpathians, about 200 km distant (Přichystal & Škrdla Reference Přichystal and Škrdla2014). XRF analyses (conducted with pXRF-device Niton XL3t900 Goldd+) confirmed this source (Müller-Scheeßel et al. Reference Müller-Scheeßel, Cheben, Filipović, Hukel'ová and Furholt2020a). In addition to the abundance of obsidian, we also found sherds of Bükk pottery, which is most commonly found in the region of obsidian sources. A co-occurrence of obsidian and Bükk pottery in southwest Slovakian Neolithic sites has been reported before (Šiška Reference Šiška1995). It seems that the access to obsidian was connected to closer social relations with the eastern Slovakian regions, which probably also involved an exchange of at least individual people.

Within the house-group excavated in 2016, obsidian (and Bükk-style pottery) was very unevenly distributed (Fig. 3). While the oldest house 132 contained a large number of stone tools and a high proportion of obsidian, this was also true for one of the two successor houses (131), while the other successor house (133) also contained a large number of stone tools, only 30 per cent of which were, however, obsidian. Also, when comparing the two assemblages from the contemporary houses 131 and 133, there was a clear concentration of specialized tools—mainly sickles, borers and scrapers—in 131, while 133 contained mainly knapping debitage, and only few tools. We interpret this as an indication for a division of labour concerning certain activities involving those specialized tools within one economic household unit. In the later phase (houses 126 and 127) stone tool quantity is very low and thus more like in the rest of Vráble. Nevertheless, differences in access to resources and social networks between farmsteads—and the continuity of these differences over generations—are obvious when comparing the lithic artefact data from the area excavated in 2016 with that of the others.

Concerning pottery, beyond the overall Younger LBK–Želiezovce-style sequence, which represents a regional trend, a correspondence analysis of the fine ware decoration patterns reveals house-group, in the 2016 trench even house-specific, patterns (Müller-Scheeßel et al. Reference Müller-Scheeßel, Cheben, Filipović, Hukel'ová and Furholt2020a). This is consistent with earlier observations about household-based self-supplying pottery production and house-styles being established in the LBK (Frirdich Reference Frirdich, Lüning and Stehli1994; Pechtl Reference Pechtl, Fowler, Harding and Hofmann2015; Strien Reference Strien, Lüning and Frirdich2005).

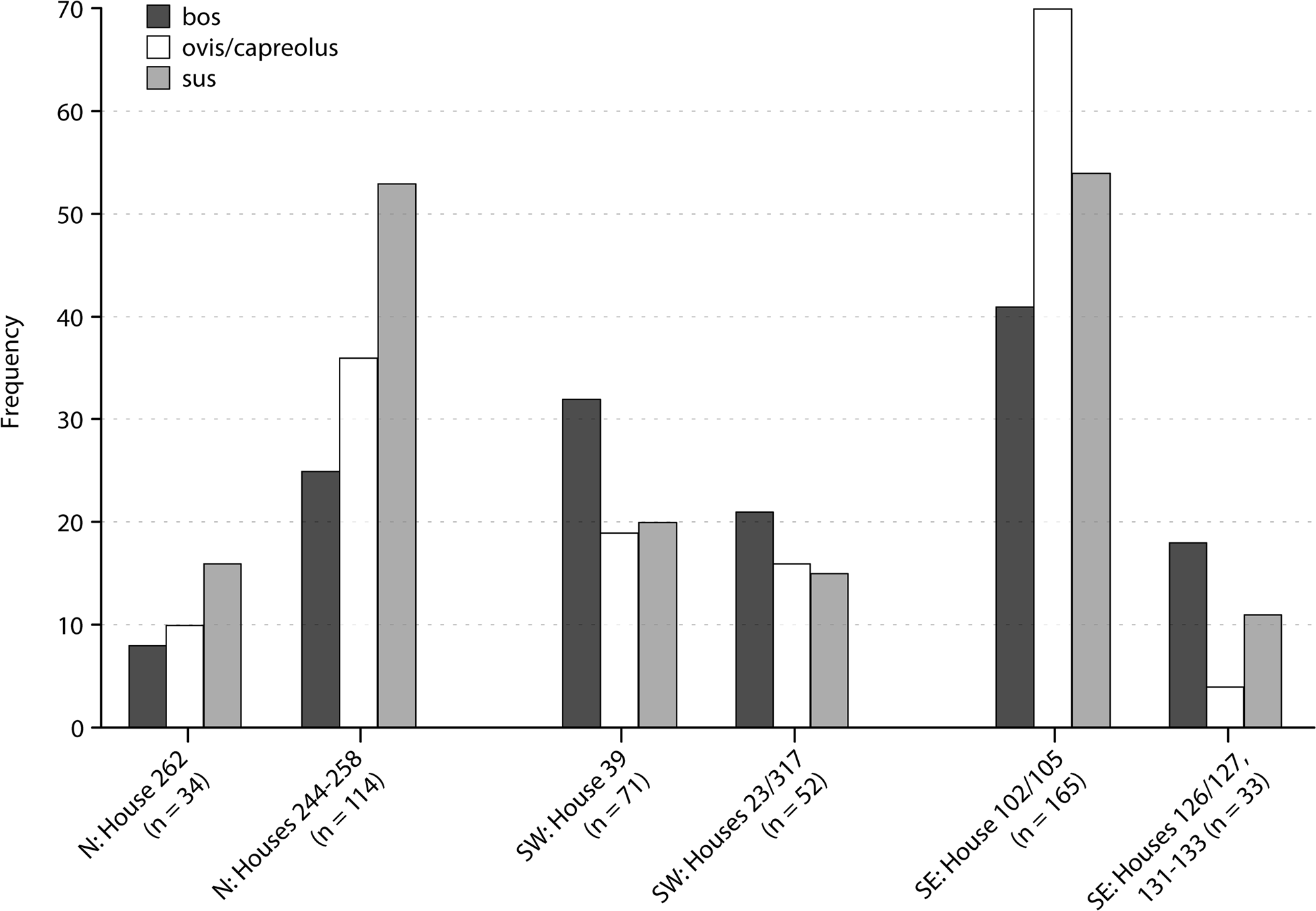

Concerning subsistence practices, both plant and animal bone remains show a corresponding variability between yards, and at the same time homogeneity within houses belonging to one house group. The faunal remains show clear differences between the house-groups excavated (Eckelmann et al. Reference Eckelmann, Schmölcke, Makarewicz, Furholt, Cheben, Müller, Bistáková, Wunderlich and Müller-Scheeßelin press), while the three settlement parts (that is the north, southwest and southeast parts) show different main domestic animal species (Fig. 5). With their faunal spectra, the yards belonging to the same settlement part are more similar to each other than to those from the other settlement parts. For example, in both house-groups uncovered by the 2014 excavation of the northern settlement, pig is the most frequent species, while in all houses in the southwestern settlement part, cattle predominates. In the southeast, sheep and goat are dominant, with the exception of houses 126/127/131–133, which however share the elevated proportion of pigs with the other houses in the southeast settlement part (Eckelmann et al. Reference Eckelmann, Schmölcke, Makarewicz, Furholt, Cheben, Müller, Bistáková, Wunderlich and Müller-Scheeßelin press). While the count of discernable bones is relatively low, there is consistency in the pattern when broken down on the level of individual houses within a house group. A similar pattern is to be seen when it comes to plant remains (Filipović et al. Reference Filipović, Kroll, Kirleis, Furholt, Cheben, Müller, Bistáková, Wunderlich and Müller-Scheeßelin press). Emmer and Einkorn are the most frequent cereals found, but their proportion differs greatly between house-groups, while being stable within them (Mueller-Scheeßel et al. Reference Müller-Scheeßel, Cheben, Filipović, Hukel'ová and Furholt2020a).

Figure 5. NISP numbers for animal bones in the different house groups of Vráble.

While all these datasets just discussed could, each on its own, be disputed, they all show at the current state a consistent pattern, indicating a strong social and economic autonomy of the farmsteads in Vráble, expressed through farmstead-specific access-patterns to raw materials, crop-breeding strategies and traditions of pottery decoration. Only when it comes to animal-exploitation strategies does there seem to be some form of integration between farmsteads in the same settlement part. This overall autonomy in economic practices and material production is consistent with the spatially isolated position of each farmstead in relation to the others, suggested by the dating results (see above).

Communality in Vráble: neighbourhood and village communities

After highlighting the strength of household or farmstead autonomy in Vráble, we will examine indications for more collective social institutions at the level of the village or settlement part (that is, the southwestern, the northern and the southeastern) communities. We will first discuss indications for institutions of communal sharing, and then examine collective action, as it is visible in the construction of the enclosure surrounding the southwest settlement part.

First, we would like to argue that the three spatially separate but equally shaped and sized contemporary settlement parts of Vráble refer to an intermediate level of social organization between the households, below the whole settlement. The three settlement parts can probably best be characterized as ‘neighbourhoods’ within an overall settlement community, as they are tied together by their spatial proximity, and a common concept of space, but still spatially separated, most visibly by the enclosure in the later phase. The concept of ‘clustered neighbourhoods’ has been used to characterize central Anatolian Neolithic settlements, where it refers to spatially bounded areas of more intense social interaction, within larger settlements (e.g. Düring Reference Düring2011, 116–18). While neighbourhoods are defined as co-habitation groups, they are probably knitted together, or separated by other kinds of social ties. Lineages have traditionally been highlighted as a main principle of social organization in the European and southwest Asian Neolithic. While this principle is easily associated with the southwest Asian and the Balkanic Tell settlements, they also seem to be visible in the farmstead structure found in Vráble, if materialized in different ways. Here, analogous to the tell settlements, a specific area, the yard, is kept by one social group—with similar preferences towards pottery style, subsistence pattern and raw-material supply—over several generations, which indicates a lineage-based inheritance system at the level of the farmstead.

The existence of neighbourhoods in LBK contexts has been suggested by Czerniak (Reference Czerniak, Amkreutz, Haack and Hofmann2016) for the site of Targowisko in Poland, and by Hofmann (Reference Hofmann2016) and, though not explicitly, by Bogaard et al. (Reference Bogaard, Krause and Strien2011) for Vaihingen/Enz, Germany. Vráble does provide another, very visible example of a division of the settlement into neighbourhoods, which are clustered spatially, show signs of an alignment of practices within, indicated by the faunal spectra (see above) and collective action in the form of enclosure construction.

In addition, we can expect communal sharing to be practised mainly within these neighbourhoods. In the 2016 excavation area, we found four beehive-shaped pits (Fig. 6). This specific type of storage container is known from ethnography for its specific function (Kriegler Reference Kriegler1929). Because of carbon dioxide forming during the anaerobic decomposition of the outermost layers of grain, such pits create a well-sealed environment in which cereals can be stored for many years (Bowen et al. Reference Bowen and Wood1968). Yet, once opened, these conservational properties are gone, and the whole volume of grains needs to be emptied and used (or it will otherwise perish). In the 2016 excavation area, we found one of these beehive-shaped pits per house, and the magnetic plan indicates a similar distribution of such pits evenly across the settlement.Footnote 3 So, while they seem to be associated with individual households, every opening must have been shared with other farmsteads, reinforcing a communal idea. In contrast, in the nearby Bronze Age settlement of Vráble-Fidvár there are areas with enormous concentrations of such pits (Bátora et al. Reference Bátora, Behrens, Gresky, Kneisel, Kirleis, Dal Corso, Taylor and Tiedtke2012, 114, fig. 5), indicating more centralized food storage, while in the Neolithic period in Vráble, storage is decentrally located, creating a link between farmstead autonomy and communal sharing. Similar arguments for the sharing of resources across farmstead boundaries have to be made for cattle, that, when slaughtered, provide too much meat for one farmstead to consume, unless cost-intensive preservation measures are applied (Russell Reference Russell and Bailey1998).

Figure 6. Profile through a beehive-shaped storage pit, from the excavation area of 2016.

The special significance of the enclosure

Within the history of Vráble, the construction of a ditched and palisaded enclosure around the southwest settlement took place towards its end. The enclosure is associated with depositions of human bodies, some of which were placed on the bottom of one of the ditches, and thus it was possible to determine a terminus ante quem for its filling. The human remains from the ditch date around 5075 bc, others, from burials placed beside yet clearly oriented along the ditch, date slightly later, around 5050–5000 bc (Müller-Scheeßel & Hukel'ová Reference Müller-Scheeßel, Hukel'ová, Furholt, Cheben, Müller, Bistáková, Wunderlich and Müller-Scheeßelin press).

The enclosure consists of a double ditch system with a palisade (see Fig. 1). It is 1.4 km long and thus probably constituted a community-wide group effort, at least encompassing those people living within the enclosed neighbourhood. It represents a complex structure with more layers of meaning than just being a physical barrier or fortification of a settlement. The outer ditch was about 2.5–3.5 m wide and its bottom is on average 1.5 m below the modern surface. In profile sections, a distinct re-cutting is visible which changed the profile of the ditch from a trough shape to a more V-shaped one. The inner ditch is much smaller and only 1.5 m wide and its bottom 0.7 m below today's surface. 14C dates from human bones in the filling of both ditches (see below) point towards their contemporaneity. In contrast, a burial disturbing the course of the palisade suggests—assuming the burial activities were all roughly contemporaneous, as indicated by the 14C dates—that the latter had already decayed or been removed when the deposition took place. Therefore, it seems likely that the palisade constituted the original demarcation of the settlement, which was replaced at a later stage by the two ditches.

The significance of the ditch system was marked by burials and depositions of human bodies and body parts within and beside it. In the 2017 campaign, we excavated two of the five entrance areas and found at least 16 individuals in the filling of the two parallel ditches as well as beside them (see Müller-Scheeßel & Hukel'ová Reference Müller-Scheeßel, Hukel'ová, Furholt, Cheben, Müller, Bistáková, Wunderlich and Müller-Scheeßelin press; Fig. 7). The patterns of body deposition reveal at least two clearly distinct categories of ritual treatment of human remains. The first (Fig. 7a–c) corresponds to the known LBK burial custom, that is, a crouched individual on its left side in a shallow burial pit with a few grave goods. Six of these typical LBK burials are distributed on both sides of the ditch. Instances of disarticulated parts of some of the bodies suggest that they were laid down on some kind of platform within the pit. Animal gnawing marks corroborate the fact that the bodies were not immediately covered. The second category consists of four headless individuals (Figs 7d–e & 8), who were laid in a stretched-out position on the very bottom of the ditch, without any grave goods. Their deposition coincides with the recutting of the ditch, or occurred not much later. While one of the four headless individuals was partly disarticulated, due to post-depositional disturbances, there is a pattern. In both entrance areas into the enclosure excavated in 2017, we found in the terminal part of the ditch to the west of the entrance two individuals stretched out, headless, with their feet directed to each other.

Figure 7. Burials and depositions found near the enclosure ditch: (a–c) regular LBK burials; (d–e) headless burials in the ditch; (f) burial in a long pit within the settlement.

Figure 8. Two headless burials in the western ditch, close to the second excavated entrance, seen in front of the ditch profile.

Furthermore, depositions of single human bones, and sometimes larger body parts, were found in the filling of the ditches. These finds are more complicated to classify, as they may represent potentially diverse depositional processes. For instance, they may represent older burials, disturbed and re-deposited during the digging of the ditch, or individuals that remained on the ditch bank for a longer period of time, so that only very few bones had the chance to be sedimented in the ditch filling and to survive. Or they may represent an alternative approach to deposition, or to disposing of human bodies.

Away from the area of the ditch, there are single human bones within the settlement, close to the houses, which are mixed into the usual settlement waste. We also found two human skeletons in long pits (Fig. 7f).

The physical anthropological examination of these human remains by Zusanna Hukel'ová (Müller-Scheeßel & Hukel'ová Reference Müller-Scheeßel, Hukel'ová, Furholt, Cheben, Müller, Bistáková, Wunderlich and Müller-Scheeßelin press) found the presence of all age groups and both sexes in all groups. Four individuals from Vráble showed signs of probable violence-induced trauma on the skeletal material, none of which was perimortal, indicating that conflict and violence were experienced by the inhabitants. The four headless individuals did not show any cut-marks on the remaining vertebra bones, but the upper atlas was missing, indicating that the heads were removed in a state of partial, not total decomposition. The anthropological study has shown that three of the four headless individuals showed spine deformations (Müller-Scheeßel & Hukel'ová Reference Müller-Scheeßel, Hukel'ová, Furholt, Cheben, Müller, Bistáková, Wunderlich and Müller-Scheeßelin press). The headless burials might thus represent a group of people set apart from the others by a different corporeal appearance.

The regular burials were found beside the ditch, both outside and inside, and one especially richly equipped adult male individual (with six pottery vessels and one flint blade) was found in the middle of the largest entrance. From the 14C dates, it could very well be that this deposition represents the first of the regular burials. People literally had to step over his dead body to enter the settlement. This differential treatment of human remains suggests the existence of different categories of people within the settlement community. The social composition of LBK communities has been demonstrated to be variable (e.g. Bickle & Whittle Reference Bickle and Whittle2013). A more widely socially fluid setting of LBK communities is to be expected (Furholt Reference Furholt2018). Different relations between local and non-local individuals have been found using strontium isotope analyses (for a summary, Bickle & Whittle Reference Bickle and Whittle2013), and while patrilocal marriage patterns are often been postulated (Bentley et al. Reference Bentley, Bickle and Fibiger2012; Brandt et al. Reference Brandt, Knipper, Nicklisch, Ganslmeier, Klamm, Alt, Whittle and Bickle2014; Pavúk Reference Pavúk1972), a wider spectrum of factors influencing mobility patterns is to be expected (Bickle Reference Bickle2019; Bickle & Whittle Reference Bickle and Whittle2013; Gomart et al. Reference Gomart, Hachem, Hamon, Giligny and Ilett2015; Hofmann Reference Hofmann2016). This might include long-distance relocation of individuals, as indicated by the Bükk pottery referred to earlier. Nevertheless, the differential categorizations of people in Vráble could also stem from internal social mechanisms, without necessarily reflecting the relation between local and non-local individuals. Isotope and DNA studies of the individuals from Vráble are currently under way.

The human bodies and body parts from Vráble have to be seen in the context of contemporary features in other settlement sites. In Herxheim in southwestern Germany, more than 500 individuals found so far are mostly disarticulated and partly articulated body parts, found in the filling of the enclosure ditch (Orschiedt & Haidle Reference Orschiedt, Haidle, Schulting and Fibiger2012; Zeeb-Lanz Reference Zeeb-Lanz2016). A ritual background is likely, as specific body parts were more frequently represented than others, especially skulls and skull caps. There is currently a heated debate on the presence and interpretation of signs of physical violence visible on the bones (Orschiedt & Haidle Reference Orschiedt, Haidle, Schulting and Fibiger2012; Zeeb-Lanz Reference Zeeb-Lanz2019). However, both pottery style and stable isotope analyses (Turck et al. Reference Turck, Kober, Kontny, Haack, Zeeb-Lanz, Kaiser, Burger and Schier2012) strongly indicate that the Herxheim human remains do not reflect one village population; rather it served as a trans-regional place of gathering and ritual. In Asparn-Schletz, Austria, the ditch was filled with human remains (67 individuals excavated) that show clear signs of extensive violence, from arrowheads or blunt force applied towards the head. As these individuals have been dated as living towards the end of the settlement period, experts attribute the remains to a single massacre that ended village history (Teschler-Nicola Reference Teschler-Nicola, Schulting and Fibiger2012). However, neither the ritual sacrificial interpretation like the one in Herxheim, nor the massacre variant of Schletz, or similar places like Schöneck-Kilianstädten (Meyer et al. Reference Meyer, Lohr, Gronenborn and Alt2015), is applicable for the Vráble case, where we find a combination of conventional burials and other forms of (ritual) deposition, with no signs of deadly violence.

Discussion: household autonomy, village institutions and social conflict

The results of the chronological analyses, as well as the examinations of subsistence strategies, access to raw materials, material culture production patterns, and the evidence from the enclosure, all point in the direction of Vráble as a village made up of strongly independent, autonomous farmsteads, as proposed in the traditional yard model. Yet there are also several indications for the strength of community-wide institutions. Firstly, even if the dating results have adjusted the numbers of contemporary houses downwards towards lower numbers, Vráble is still an extraordinary concentration of population, especially when compared to the other LBK sites in the Žitava valley (Breitenfeld Reference Breitenfeld2019), in southwest Slovakia (Pavúk Reference Pavúk, Lukes and Zvelebil2004) and the whole LBK area (Petrasch Reference Petrasch, Cladders, Stäuble, Tischendorf, Wolfram, Cladders, Stäuble, Tischendorf and Wolfram2012). There is no obvious reason (ecological, strategic concerning traffic routes) that would explain why the largest settlement in the whole southern LBK area should be at this exact place. Also, as discussed above, the settlement space in Vráble is structured in what looks like three carbon copies of the same mental concept, with the same size, shape and orientation. Only during an advanced stage can a differentiation between the villages be seen in the form of the enclosure constructed around only one of the three neighbourhoods.

Within the system of social organization of Vráble, there are different, potentially contentious observations relating to social organization: the strong autonomy of the household, the importance of communal sharing, neighbourhood grouping and overall concentrated cohabitation. In line with expectations for agricultural societies (Carsten & Hugh-Jones Reference Carsten, Hugh-Jones, Carsten and Hugh-Jones1995, 4; Ensor Reference Ensor2011, 213–16), the case study of Vráble shows both the social and economic importance of farmsteads as single households. In economic terms, we see a high degree of independence and also exclusionary strategies (cf. Blanton et al. Reference Blanton, Feinman, Kowalewski and Peregrine1996) among the individual household units (access to and use of resources, animals, crops). While we can see a clear emphasis on the individuality and singularity of the farmsteads in Vráble, the overarching social organization is contrarily marked by an emphasis of communal strategies and the importance of overarching social groups (compare Blanton et al. Reference Blanton, Feinman, Kowalewski and Peregrine1996; Saitta Reference Saitta1997). The storage pits and presumably collective consumption of slaughtered animals indicate the importance of resources and land connected to the social institutions above household-level, which were bound together by sharing activities. Both a shared claim to land and resources as well as sharing economies were repeatedly described as being of high importance within the maintenance of socially bound groups (for example, clans; e.g. Godelier Reference Godelier2012; Leach Reference Leach2004; Strathern et al. Reference Strathern, Stewart and Shapiro2018). In Vráble this sharing most probably was practised within each neighbourhood. One of the main responsibilities of broader larger social units, e.g. kin-groups such as lineages or clans, is the provision of social security and cohesion among its members. Cooperative action and the establishment of commemorative places (the enclosure) are all well-known examples of the manifold strategies to create communal institutions and/or kinship structures such as clans and lineages (e.g. Gunawan Reference Gunawan2000; Sahlins Reference Sahlins2013).

The presence of collective storage pits among, presumably, each household could represent the joint and interconnected efforts of the otherwise independent farmsteads to provide economic security. The erection of long houses (possibly communal building activities) and the construction of a ditch system all point towards an enduring performative creation and maintenance of larger social units, perhaps constituted by unilineal descent groups (compare Souvatzi Reference Souvatzi2017). The spatial separation of the different neigbourhoods also points towards a social differentiation within or between these units, which might hint towards the presence of either sub-divisions of one descent group, or several descent groups being present in Vráble.

Despite these hints on the importance of communal frameworks, the fact that only one of the three neighbourhoods is enclosed, although they were all still occupied at the time of its construction (5075 bc), makes the enclosure a complicated issue when it comes to its relation to group identities. While the whole enclosure has five entrances, they are all facing away from the two other contemporary neighbourhoods (Fig. 1), and there is no entrance at all along the eastern and northern parts of the enclosures, where it is close to these settlements. Clearly the enclosure is constructed to block off one neighbourhood from the two others. So, if it is to be seen as a sign of multi-farmstead cooperation and higher-level (i.e. neighbourhood- or settlement-wide) identity formation, this is probably only relating to the inhabitants of the southwest neighbourhood. Thus, the enclosure can be interpreted as a sign of marked tension between the three neighbourhoods.

Social organization in a wider context

Overall, there seems to be a tension between the household, or farmstead, as an economically independent unit, and higher-level institutions, probably on two scales, namely the neighbourhood, and the overall village community. This does not seem exceptional; in fact such tensions are widely believed to have driven much of the early Neolithic social dynamics in southeastern Europe. For example, Halstead (Reference Halstead2006) discusses a constant tension between household autonomy and community solidarity, between sharing and hoarding in the Aegean. Leppard (Reference Leppard2014), dealing with the same region, makes use of the old idea of the effects of Neolithic delayed return economies in a contextual background governed by ideologies of sharing and communality (Peterson Reference Peterson1993; Widlok Reference Widlok2016; Woodburn Reference Woodburn1982), and argues that the Neolithic subsistence economy must have led to the emergence of and conflicts over systems of ownership of resources, in which small-group or household interest might not have been easily brought in accordance with the interests of the whole community, and that ‘the contradiction between imperatives to share and a desire to reap benefits from delayed-return food production could potentially have rendered Early Neolithic societies … fragile with intra- … community tension a possible outcome’ (Leppard Reference Leppard2014, 492).

In Vráble, we could make this explicit. Early on, some farmsteads start monopolizing supra-regional resources like the acquisition of obsidian and trans-regional contacts with communities with Bükk pottery. At the height of the agglomeration process, around 5075 bc, the southwest part of the settlement started to identify itself as in opposition to the other neighbourhoods, the enclosure marking this. The setting of formal burials, which is not observed in the other parts of the settlement, makes the statement of being different from the others even more pronounced. These burials in turn also indicate the development of some form of social inequalities between inhabitants of that part of the settlement. Probably this development was triggered by the increasing population and challenged the originally primarily acephalous way of life, which might be harder to maintain with a growing population number.

It seems reasonable to assume such a conflict brooding in other Neolithic village communities in southeastern and central Europe as well. Looking at the archaeological evidence, the relation between different social units within Neolithic village communities shows a high degree of variability, but also certain trends that are of importance for our understanding of the Vráble community. During the establishment of Neolithic economies in southwest Asia, large agglomerations of settlement appeared, some of which showed strong settlement-wide social institutions, visibly standardized house forms, building techniques, internal organization, etc. (e.g. Düring Reference Düring2011). In central Anatolia, for example, we find a threefold hierarchical structure of social organizational units, namely the household (identified with the individual house), the house-group, or neighbourhood, and the whole village community (Düring Reference Düring2011, 116). In the following pottery Neolithic, during which the expansion of Neolithic ways of life into Europe was triggered, the role of the household is believed to have been strengthened at the cost of the two other institutional levels (Furholt Reference Furholt, Gori and Ivanova2017; Marciniak et al. Reference Marciniak, Barański, Bayliss and Czerniak2015). There seems to be a spatial southeast–northwest as well as a temporal trajectory with an increasing household autonomy the further northwest we go, and stronger community-wide institutions in the southeast and in earlier settlements (Furholt Reference Furholt2016). Still, apart from this overall tendency, the constant tension Halstead and Leppard refer to might have played out in different ways in different periods. In the early Neolithic of the Balkans, Starčevo settlement plans show little signs of any overall order, while in the Balkan Late Neolithic, larger and more orderly arranged villages appear, connected, among others, to Vinča materials (Draşovean & Schier Reference Draşovean, Schier and Hansen2010; Hansen et al. Reference Hansen, Reingruber and Toderaş2009; Lichardus Reference Lichardus1996; Mischka Reference Mischka2009). While the actual settlement layouts are variable, there are often settlement-wide patterns determining the position of each house, indicating strong village-wide institutions, at the cost of household autonomy. In the Butmir site of Okolište, house groups are postulated that show division of labour (Arponen et al. Reference Arponen, Müller and Hofmann2015; Müller et al. Reference Müller, Hofmann, Müller-Scheeßel, Rassmann and Anders2013a). In the LBK area, contemporary to Vinča and Butmir further south, patterned structures of house placement are much less frequent, and strongly debated—see the yard-model versus rows-of-houses-model referred to above. In any case, regular village shapes, like the linear variant in Okolište (Hofmann Reference Hofmann2013; Müller et al. Reference Müller, Rassmann, Kujundzic-Vejzagic, Müller, Rassmann and Hofmann2013b), or circular arrangements of houses (Hofmann et al. Reference Hofmann, Medović and Furholt2019), are extremely rare in the LBK area, Vráble with its three similar trapezoid shapes probably being one of the best examples. Also neighbourhoods are not often identified in LBK settlements, except for a few striking cases. They take very different forms. In Cuiry-Les Chaudardes, France, two groups of houses, which are spatially separated and have different house types (small versus larger ones), are associated with different subsistence patterns (hunting versus domesticated resource exploitation: Gomart et al. Reference Gomart, Hachem, Hamon, Giligny and Ilett2015). They are also differentiated via different pottery manufacture techniques. These two groups are interpreted by Gomart et al. (Reference Gomart, Hachem, Hamon, Giligny and Ilett2015) as representing newcomers versus more established households, who engage in reciprocal exchange of their respective surplus production. A very different system of intra-site subgroups is postulated in the LBK settlement of Vaihingen/Enz in southwestern Germany (Bogaard et al. Reference Bogaard, Krause and Strien2011), where specific traditions of pottery decoration can be associated with differential access to different fields. These ‘clans’ are shown to occupy different areas in the settlement, with some overlap. They are supposed to have come to and left the community in Vaihingen at different times and are also associated with different regional LBK pottery sub-styles. Such a translocal pattern of clans or lineage groups could be present in Vráble too, but they have not yet been detected in the pottery styles, as in southwest Slovakia the late LBK and Želiezovce is regionally rather uniform.

However, in the great majority of LBK settlements spatial subgroups, neighbourhoods, are not visible in the archaeological material. We would like to argue that this reflects a broader socio-historical setting, and that in the period 5350–5000 bc the main difference between the Balkans (Vinča) and central Europe (LBK), is that household autonomy is decidedly stronger in the northwest, while community-wide institutions are more visible in the southeast. Taking into account a tension between household autonomy and village solidarity as inherent in Neolithic economies, Vráble constitutes an example in which the latter is more marked than in most other LBK settlements, but less so than in the Balkanic tradition. While the unusually large settlement concentration, as well as the separation into neighbourhoods, reflects the strength of southern traditions, the spatial isolation and differentiation of subsistence practices and material production between the farmsteads within these neighbourhoods accentuates the strength of small-scale autonomy, which is more similar to the central European patterns. The negotiation of particularist farmstead interests and communal institutions and village solidarity is probably more antagonistic, less resolvable than in other places, where one or the other eventually gets an upper hand, or settlements break up. A way to mitigate the tension could be the promotion of neighbourhood identity, as a smaller social unit, substituting for the larger overall village community. It is at the neighbourhood level, where communality and sharing—exemplified by beehive storage pits, by the construction of a complex enclosure system—are acted out. But in Vráble the development of these neighborhood-ties obviously is also linked to a contradictory social differentiation within the neighbourhoods. As described, the people buried or deposited in and along the enclosure are categorized differently, maybe according to their physical appearance, or capacities. In addition, the monopolization of trans-regional contacts and sought-after exotic resources by single farmsteads will have undermined neighbourhood solidarity. Thus the new neighbourhood ideology failed as the social contradictions increased: around 4950 bc, Vráble was abandoned.

The antagonism between the three neighbourhoods in Vráble becomes most visible in the late phase, when the enclosure around the southwest part of settlement is clearly directed against the two other neighbourhoods. This might be a strategy to avoid the social fission most other LBK communities chose, alongside restriction to a smaller village population sizes in the first place. Overall, the increase in settlement enclosures as well as their association with violence, or ritual practices involving dead human bodies in the late LBK, could thus also be ascribed to rising intra-community tensions rather than the inter-community conflict that is usually assumed (e.g. Golitko & Keeley Reference Golitko and Keeley2007). There were, however, different ways of reconciling the tension between communality and particularist interests of individual farmsteads. In Vráble, the inhabitants chose to retain the overall concentration of settlement, but to mark or differentiate communities more strongly at a lower level. There is not only the clear fencing-off of one settlement part (or neighbourhood); in addition, the symbolic charging of the neighbourhood demarcation with dead human bodies is connected to social differentiation. The different categories of burials/deposition of human bodies and body parts reflect the definition of different kinds of people, with regular burials with burial goods as opposed to headless people at the bottom of the trench, and perhaps a third category being people treated like settlement debris (or alternatively, deliberately fragmented and distributed in the ditch).

This represents a situation that is historically specific for the communities in Vráble. However, it cannot be overlooked that there are parallels to developments in other places. It is puzzling that there is such a recurrent association of enclosure ditches and human bodies in the later LBK period. Yet, while there is evidence for physical violence being associated with these enclosures, as in Schletz (Teschler-Nicola Reference Teschler-Nicola, Schulting and Fibiger2012) and Kilianstädten (Meyer et al. Reference Meyer, Lohr, Gronenborn and Alt2015), there is definitely more to their interpretation than a suddenly emerging need for fortification against an outside enemy because of a rising degree of conflict and violence. As Herxheim (Zeeb-Lanz Reference Zeeb-Lanz2016) and Vráble show, the phenomenon of bodies in enclosure ditches is too complex to be explained by the theory of emerging warfare (Golitko & Keeley Reference Golitko and Keeley2007).

Instead, we would argue that there were overall structural settings in Early Neolithic LBK settlements which created parallel sets of social conflict, like the one discussed here, between household, village communities and intermediate social groups, most virulent probably in the larger settlement agglomerations. And there might have been a set of ideas, which facilitated recurring associations between physical entities—for example settlement space, human bodies, etc.—which then could play out in very different ways in different contexts.

Thus it seems that the late LBK enclosures were associated with death and human bodies more generally, while the individual manifestations of this association are variable. So while the depositions in and near the Vráble enclosure clearly represent a symbolical charging of the physical construction, they also evoke a categorization of humans into at least two different categories. In other places, much more complex port-mortem manipulations of bodies (Herxheim), or mutilations (Kilianstädten), represent different manifestations of the same overall theme. This is not to say that inter-group violence did not exist, as shown by the cases of Talheim (Bentley et al. Reference Bentley, Wahl, Price and Atkinson2008), Halberstadt-Sonntagsfeld (Meyer et al. Reference Meyer, Knipper and Nicklisch2018) and Schletz. However, only in Schletz is this associated with an enclosure. Overall, none of these phenomena seem to have been especially long-lasting, or successful when it comes to resolving any kind of underlying social tension, as they mark the late phase of LBK-style settlement. In many regions, this is followed by much more dispersed settlement structures; in others transformed versions of relatively similar patterns continued to exist for some time (e.g. Eythra: Stäuble & Veit Reference Stäuble and Veit2016). In the Žitava valley, Lengyel settlement is in general much less concentrated than during the LBK period: for example, close to Vráble a loose cluster of four Lengyel houses is visible in the magnetic plan.

Conclusion

Vráble is an early Neolithic settlement, dated to 5250–4950 cal. bc, associated with the Younger LBK and Želiezovce pottery styles. The available 14C dates indicate a gradual increase in house numbers until 5050 bc, followed by a steep decline and abandonment of the site around 4950 bc. At its peak, we assume the presence of about 70 longhouses. Vráble consists of three settlement parts, which we interpret as contemporary neighbourhoods within one community. In its LBK context, Vráble represents an extraordinarily concentrated village, even if it is made up of economically autonomous farmsteads. The elements of settlement size, non-random settlement shape and the presence of neighbourhoods show a more important role of southern, Balkanic or Near Eastern traditions that more strongly emphasize village communality than is visible in most other LBK sites. Assuming a general tension between household autonomy and village communality in Neolithic economies, Vráble potentially represents a stronger variant of such tensions, which might have unfolded over its 300 years of history with different strategies of reconciliation. One such strategy could have been a stronger neighbourhood demarcation through an enclosure directed against the other inhabitants of the village. A second strategy visible in Vráble is a social categorization of its inhabitants through differential body treatments in depositions. Other strategies, less visible in the archaeological material, are to be assumed.

Different phases of Vráble settlement development could be identified. First, the foundation of the settlement around 5250 bc; second, the increase in population contrasting the decrease of other smaller domestic sites in the Žitava valley; third, during this agglomeration process the separation of and internal differentiation and conflict within one of the neighborhoods of Vráble that we interpret as being driven by growing particularist social interests; and fourth, the social collapse and abandonment of the site, probably as a consequence of rising social tension between and within the Vráble neighbourhoods.

Eventually, social fission and socially driven particularization of an individual neighbourhood signal the end of settlement in Vráble. Later on, after a period of dispersed Lengyel settlement patterns, new forms of communal institutions might again be seen in the circular enclosures of the Lengyel period around 4750 bc (Řídký et al. Reference Řídký, Květina, Limburský, Končelová, Burgert and Šumberová2019).

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge funding of CRC1266 by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation, Project 2901391021) and the VEGA-Project 2/0107/17.