Introduction

This paper takes a theoretical approach to investigating the encounter with foreign things within local landscapes. Human thoughts and identities are in part constructed by relational interactions with material culture. Thus, while it is true that humans make things, it is also true that the knowledge of how to make things (e.g. in what form, what type, what functions are necessary) is based on a familiarity with the already existing things in the world to which individuals within a particular group are exposed. This predisposition to a particular material reality affects the way people conceptualize the world and moulds the perception of what types of things—old and new—one has the potential to produce. When people become entangled with new things that are introduced into their lived environment, the picture becomes more complex. The potential arises for adaptation or alteration of human behaviours and social practices. In the study that follows, the recently discovered imported Cypriot pithoi from the Late Bronze Age (LB, hereafter) site of Tel Burna in the southern Levant will serve as a case study, and the concepts of object biography and agency as explanatory models, for investigating the effects that the encounter with foreign things could have on local traditions.

Tel Burna and the southern Levant in the LB

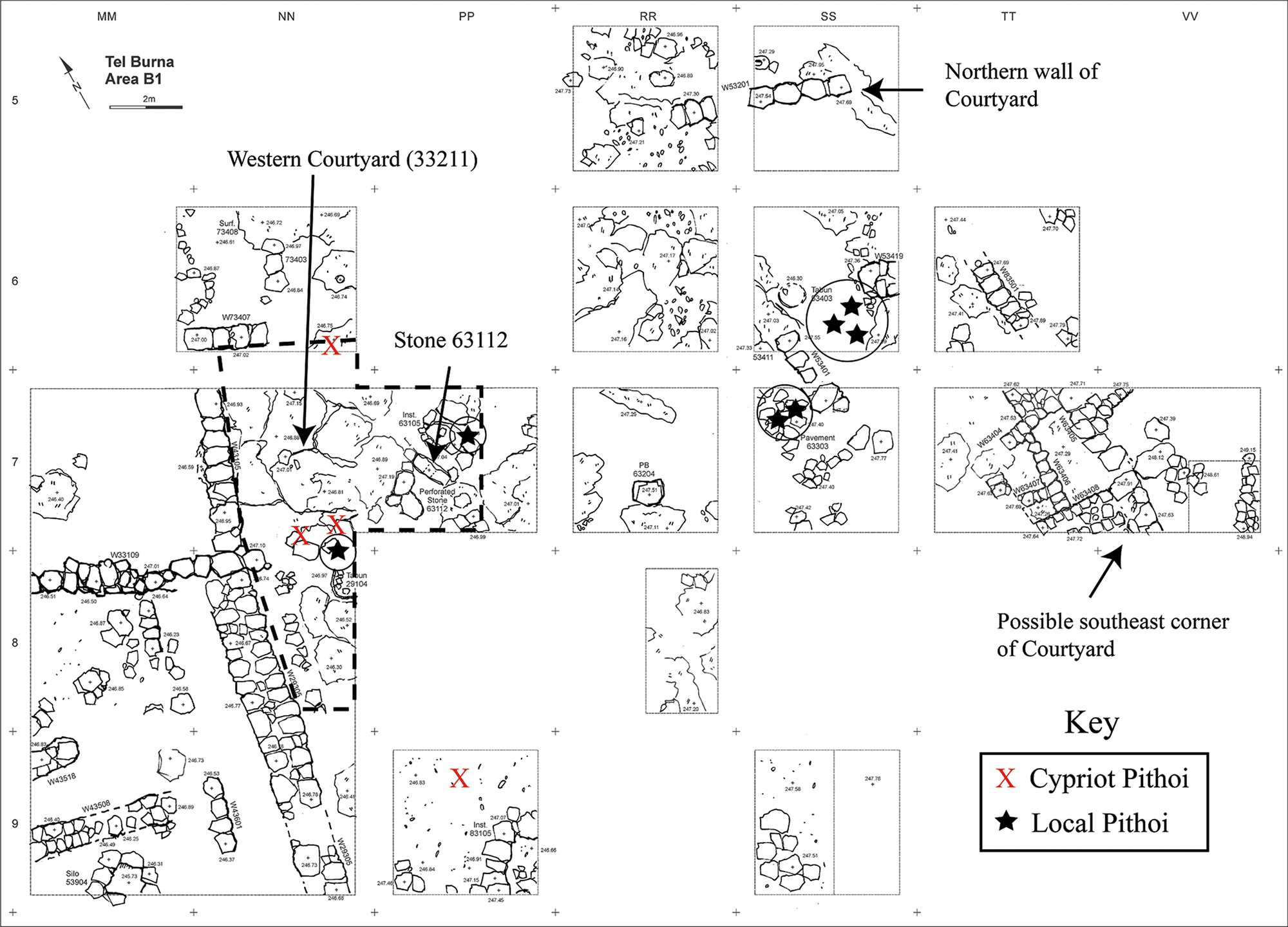

Tel Burna, located in the Shephelah region of the southern Levant, was a small 6 ha site geographically situated between the coastal plain to the west and the inland mountains to the east (Fig. 1). The site was inhabited from the Early Bronze Age through the Persian period (Uziel & Shai Reference Uziel and Shai2010). The LB settlement, initially founded in the fourteenth century bce, reached its peak in the thirteenth century bce, as attested to by the fact that the majority of the LB finds date to that time (see McKinny et al. Reference McKinny, Tavger, Shai, Maeir, Shai and McKinny2019). LB occupation at the site has primarily been uncovered in Area B1, located just to the west and below the summit of the tell (Fig. 2).

Figure 1. The Shephelah region in the southern Levant and the location of the site, Tel Burna. (Map: Jane Gaastra.)

Figure 2. Plan of Area B1 at Tel Burna, the location of the courtyard within which the pithoi were retrieved.

Compared to other nearby LB sites of the Shephelah which functioned as important inland centres (e.g. Lachish, Tell-es-Safi/Gath, Gezer), Tel Burna does not stand out as being particularly significant, likely neither a first- nor second-order site (Uziel et al. Reference Uziel, Shai, Cassuto, Spencer, Mullins and Brody2014, 300, table 1). Yet, while it may not have had substantial socio-political status or power in the region, nor was it located near the coast, the large quantity of seaborne imports that were found at Tel Burna, mainly from Cyprus, indicate it was well connected to the eastern Mediterranean coastal networks.Footnote 1 Among the site's many Cypriot imports were four imported Cypriot pithoi (Shai et al. Reference Shai, McKinny and Spigelman2019). In addition to these pithoi, another eight locally manufactured pithoi were identified during the ongoing analysis of the excavated LB material from Area B1. The relationship between these local and imported pithoi will be the focus of this study.

Overall, the southern Levant during the LB was well integrated into the international maritime trade networks of the eastern Mediterranean. The many Cypriot and later Mycenaean imports to the Levant are a product of this, and the typical maritime transport container for international commerce of the LB was of a Levantine form, many of which were produced locally on southern Levantine soil (Broodbank Reference Broodbank2013, 379–80; Demesticha & Knapp Reference Demesticha and Knapp2016; Knapp Reference Knapp2018a, 135–8; Pedrazzi Reference Pedrazzi, Demesticha and Knapp2016, 57–77).Footnote 2 Relevant for this study, LB sites in the southern Levant are typified by a lack of pithoi (Bonfil Reference Bonfil, Stern and Levy1992, 31; Raban Reference Raban and Wolff2001; Shalvi et al. Reference Shalvi, Bar, Shoval and Gilboa2019), excluding perhaps the northern inland valley region of the Jordan River Valley, where the site of Hazor had many very large pithoi in use throughout the LB (Bechar Reference Bechar, Ben-Tor, Zuckerman, Bechar and Sandhaus2017, 222–3). This is in stark contrast to the Middle Bronze Age (MB, hereafter), when there is evidence for their widespread use throughout the region. How can it be explained that Tel Burna not only had rare, imported pithoi from Cyprus, but alongside those imported vessels, the site also yielded locally produced pithoi, a vessel type that was otherwise extremely rare in the region?

Through the lens of the Tel Burna pithoi, this study will focus on what a material agency approach to the pithoi can tell us about the unique archaeological record at the site and the broader socio-cultural landscape of the period. The idea that both humans and objects can each imprint themselves upon the other and induce change will be developed below, and it will be demonstrated that the imported Cypriot pithoi played active roles in the potters of Tel Burna producing local pithoi during a period when other sites in the region did not generally have pithoi.

Theory

This study begins with the following inquiry: do thingsFootnote 3 have agency? To what extent can it be said that objects act, or at least impact the way in which humans act? Taken at face value, it is easy to suggest that objects—especially inanimate ones—do not act; they are things that are made, moved and used by human subjects. Indeed, traditional approaches to material culture have tended to associate agency with active human actors (subjects with subjectivities) who act upon passive things (artefacts, objects, etc.). The past few decades, however, have witnessed more nuanced approaches to the issue of agency, what exactly objects are (in terms of their materiality and are they really just passive?), and if the fact that something is generally considered inanimate—for example, a stone, a tool, or a pot—necessarily precludes it from the possibility of having a unique biography or some form of agency.

Object biographies and human–thing relations

Research dealing with material-culture studies, which includes scholars from a broad scope of disciplines including archaeology, anthropology and sociology, has been heavily influenced by the concepts posited by Kopytoff (Reference Kopytoff and Appadurai1986) and others in The Social Life of Things (Appadurai Reference Appadurai1986) on the relationship between people and things. In essence, things can be said to have social lives or cultural biographies, as they are successfully moved about and recontextualized, coming into contact with new objects in new scenarios (Hoskins Reference Hoskins, Tilley, Keane, Küchler, Rowlands and Spyer2006; Knappett Reference Knappett2002). These ideas have been expanded in various directions, with subsequent research emphasizing notions such as object agency (Gosden Reference Gosden2005; Jones & Boivin Reference Jones, Boivin, Hicks and Beaudry2010; Knappet Reference Knappett2002; Robb Reference Robb2010; Tilley Reference Tilley, Tilley, Keane, Kuechler-Fogden, Rowlands and Spyer2006) and relatedly, actor-network-theory (Latour Reference Latour1999; Reference Latour2005).Footnote 4 Accordingly, scholars today will agree with the idea that things are not simply passive objects, but have embedded within them complex stories—social lives or biographies (Joy Reference Joy2009)—and that furthermore, objects have some form of agency, in that the material itself affects the way humans live their lives.Footnote 5

A particularly useful interpretative approach to material culture takes its cue from structuralism and the linguistic turn through comparison with language.Footnote 6 Contrasting with the processual, functionalist views on material culture (e.g. Stockhammer Reference Stockhammer2012, 7–8), this more semiotic approach understands material culture, like language, as meaningful and symbolic (e.g. Hodder Reference Hodder2013; Hodder & Hutson Reference Hodder and Hutson2003), not solely as a natural consequence of human action, but rather as a key way through which the social world is constructed (Jones & Boivin Reference Jones, Boivin, Hicks and Beaudry2010, 335–6). In this way, material culture not only presents itself as being ‘open for interpretation’ (for example, an object's function is never set in stone), but it is an active vehicle affecting and imprinting itself upon the various components of society. Thus, here too it is observed that material culture is not simply a passive, reflective aspect of social actors and realities; things are not only props, stages and backdrops for human action, they are integral to and play active roles in constituting it (so Gosden & Marshall Reference Gosden and Marshall1999, 169).

This two-way street—that material culture is both a framework for and is shaped by social action—provides an important basis in this study for understanding what happens to local traditions of a group when foreign, unfamiliar things are introduced into the local landscape. This particularly pertains to the LB Levant, which, as noted, witnessed immense cultural intermingling and the circulation of large quantities of imported ceramics from around the eastern Mediterranean. As this study is interested in the effects that the exposure to foreign elements have on the local way of doing things, it is important not only to reflect upon how we, as humans and social actors, make things, but also to acknowledge that things contribute to making us. Things are not only a part of human life; they affect and change it.Footnote 7 Since the very make-up of the things in the world is inseparable from the way individuals are moulded to think and act, it is only natural to inquire about what happens when new objects are introduced into a group's material world.

Object agency

If objects can be seen as social actors in that they construct and influence social actions that would otherwise not occur if those objects did not exist (e.g. Gell Reference Gell1998; Gosden & Marshall Reference Gosden and Marshall1999), one is compelled to ask whether this can be considered agency, and how much power do things really have over humans. Many scholars have grappled with what object agency might mean (Hoskins Reference Hoskins, Tilley, Keane, Küchler, Rowlands and Spyer2006; Joyce Reference Joyce and Shankland2012; Knappett & Malafouris Reference Knappet and Malafouris2008; Marshall Reference Marshall2008). Some see it related but inherently inferior to human agency. Thus, Gell, dealing with art and artefacts as social agents, distinguishes between primary agency (of humans) and secondary agency (of objects). In this sense, objects are an extension of personhood, and thus, according to Gell, can be conceptualized as the media through which human-derived agency is distributed (Gell Reference Gell1998; cf. Knappett Reference Knappett2002, 99). At the same time, a number of archaeologists have recently pushed back against the notion of ‘object agency’ altogether, suggesting that agency must be grounded in intentionality (e.g. Johannsen Reference Johannsen, Johannsen, Jessen and Jensen2012; Knapp Reference Knapp, Knodell and Leppard2018b, 293–4; Lindstrøm Reference Lindstrøm2015; Robb Reference Robb, Demarrais, Gosden and Renfew2004; Reference Robb2010, 504–5).

Actor network theory resonates particularly well here, which perceives humans and things as being relationally attached to and co-dependent on one another (Latour Reference Latour1999; van Oyen Reference van Oyen2015). Society, in other words, is not made up of people alone, but of collectives of people and things (Robb Reference Robb2010, 504–5), and while things act as intermediaries for human action, human action also imprints itself on those things. It is within this human–thing network that agency is produced and distributed (Jones & Boivin Reference Jones, Boivin, Hicks and Beaudry2010; Knappett Reference Knappett2002; see further Ingold Reference Ingold2013, 132, who prefers ‘meshwork’ over ‘network’).

Indeed, scholarship over the past decade (e.g. Knappett & Malafouris Reference Knappet and Malafouris2008) has shifted away from earlier anthropocentric views of agency (Sørensen Reference Sørensen2016; cf. Chua & Elliot Reference Chua and Elliott2015, 13–15), exploring whether material agency is really something secondary to the agency of humans. Studies have focused on how agency emerges from a coalescence of both human and non-human elements, and therefore, it is both that share responsibility for action (Knappett & Malafouris Reference Knappet and Malafouris2008, xii). These recent approaches do not necessarily aim to extend subjectivity or intentionality to the material world, nor do they consider humans to be objects; rather, they signal a shift away from trying to locate agency within either a subject or object (Jones & Cloke Reference Jones, Cloke, Knappet and Malafouris2008, 93; Knappett Reference Knappett, Knappett and Malafouris2008). Agency is thus distributed, emergent and interactive; it is a process in which material culture is entangled (Jones & Cloke Reference Jones, Cloke, Knappet and Malafouris2008, 93; Knappett Reference Knappett, Knappett and Malafouris2008; Malafouris Reference Malafouris, Knappet and Malafouris2008). Furthermore, agency is not absolute; it is not an ever-present, ‘one-size-fits-all’ property that all objects embody at all times or in all situations. Agency emerges in specific contexts, having particular consequences (Sørensen Reference Sørensen2016, 116; Reference Sørensen2018, 96–7). It is not as simple, then, as saying that agency is there and is an inherent attribute of objects. In this light, it is not that objects have agency—objects produce agency (Malafouris Reference Malafouris, Knappet and Malafouris2008).

As networks are dynamic, when new foreign elements—whether human or non-human in form—are introduced into the environment, networks have the potential to evolve and become more complex. This new material order, which Van Wijngaarden (Reference Van Wijngaarden, Maran and Stockhammer2012, 61) refers to as a crisis, can elicit further potential for change as new ideas, and possibly new material forms, are produced. Foreign and exotic objects therefore do not simply disrupt existing material relations and human-thing networks, they can enable creating new ones (Van Wijngaarden Reference Van Wijngaarden, Maran and Stockhammer2012, 61).Footnote 8 Accordingly, if a new object becomes integrated into the local repertoire of ‘things’, social actors may be compelled to modify their social practices, and as a result, their perception of the material world (e.g. Stockhammer Reference Stockhammer2012, 16).Footnote 9

Pertinent to the present study, one way in which agency can be produced is through captivation. The mere act of visualizing an object can have a profound impact on the viewer. In Gell's discussion of darshan, he develops the idea that the visual act of seeing creates a relationship and bridge between the seer and that which is seen (Gell Reference Gell1998, 116–18).Footnote 10 Captivation (Gell Reference Gell1998, 69–72) arises when a spectator becomes trapped within a visually observed object because the object embodies something that is unfamiliar, essentially indecipherable, to the observer. It is precisely this type of captivating human–object interaction that can create a sense of curiosity and emotions within the observer; when considering foreign commodities emerging in new contexts, it can spark new ideas and even elicit a desire to produce imitations (on imitations, see below). Studies on feasting have similarly emphasized that displaying prestige goods by placing them in clear view of observers is a mechanism of asserting elite authority over and identification with that object type to which other, less-privileged individuals do not regularly have access (Dietler Reference Dietler, Dietler and Hayden2001). Thus, beyond objects of art captivating viewers (as discussed by Gell), very functional commodities can do so as well.

Intent, functionality and potentiality: between objects, their producers and their users

Related to a number of the above ideas, Ingold (Reference Ingold2013) recently adopted an approach that sees making as a process of growth, one in which the makers of things learn from being situated within the world, acquiring knowledge through experiential, hands-on engagement with their material surroundings (2013, 21). Given a familiarity that makers have with their material world, individuals within a particular group may have certain intuitions regarding how things should be made and how they potentially should or could be used. But if objects are in some sense produced so as to influence people's actions and thoughts (e.g. Gell Reference Gell1998), to what extent can the outcome of this influence be predicted by the producer? Ingold eloquently argues that artefacts are not simply things that begin with an idea and end with fixed material forms. They are fluid and embody multifunctionality, and in their final material form, their meaning and use may be very far from final (Ingold Reference Ingold2013, 39). Object meaning therefore cannot adequately be explained as simple subordination to the maker's intentions (Knapp Reference Knapp, Knodell and Leppard2018b, 299–301; Olsen et al. Reference Olsen, Shanks, Webmoor and Witmore2012, 186, 189).

Indeed, in a modern consumer market, it is quite easy to imagine a situation in which a product—for example, a handmade ceramic bowl—can be used differently from the original intent of producer. Regardless of the maker's intent, objects are more often than not polycausal. Embedded within them, a world of possible functions and meanings exists (Stockhammer Reference Stockhammer2012, 8). Mackenzie's study of string bags in Papua New Guinea demonstrates this idea well (Mackenzie Reference MacKenzie1991; cf. Hoskins Reference Hoskins, Tilley, Keane, Küchler, Rowlands and Spyer2006, 79). This specific bag type was used so diversely, one could hardly say these bags were produced, or were intended to be produced, for a single reason. For example, they could be used for carrying young children, vegetables, fish or firewood, and while they were carried by both men and women, women tended to carry them from the head while men carried them from the shoulder. Precisely because of this object type's potential use in so many different ways, it mediates a plurality of complex social relationships and as a result, it takes on a multiplicity of variegated cultural connotations (Hoskins Reference Hoskins, Tilley, Keane, Küchler, Rowlands and Spyer2006, 79). Thus, the use and meaning of these bags is beyond the makers’ control.

This example demonstrates that the life that an object takes on is not necessarily the life that the object's maker intended for it; its biography and meaning cannot be predetermined. Objects, their functions and their meanings are not static. This is precisely what creates a dynamic situation of cultural intercourse in which new objects that are introduced into a social landscape can have an impact—and an unpredictable one for that matter—on the local group. Specifically related to the importation of exotic commodities, even inexpensive objects that are not considered ‘luxurious’ by the manufacturers can be transformed into ‘exotic’ and ‘special’ in a new, foreign context, for example as can be witnessed in the special consumption of Coca-Cola and the prestige associated with Coca-Cola bottles in rural east Africa (Dietler Reference Dietler and Twiss2007, 228–9) and similarly, the use of red Fanta as daily food offerings for statues of deities in present-day Thailand (Ferguson & Ayuttacorn Reference Ferguson and Ayuttacorn2021, 658).Footnote 11 Disassociated from their makers’ intent and their original contexts, the potential for new meanings and uses is apparent.

While in no way all-encompassing, this brief investigation of object biographies and agency will dictate the discussion of Tel Burna pithoi below. The study will first proceed with the presentation of the data on the pithoi.

Data

During the 2012 season, two Cypriot pithoi were discovered, in situ, standing on a prominent high place in the western part of the open-air courtyard of Building 29305 in Area B1, a complex which dates to the thirteenth century bce. These pithoi have been thoroughly analysed and published elsewhere (Shai et al. Reference Shai, McKinny and Spigelman2019). In addition, two other Cypriot pithoi were found in the courtyard. Subsequently, at least eight locally produced pithoi have been identified within the same context as well.Footnote 12

Cypriot pithoi

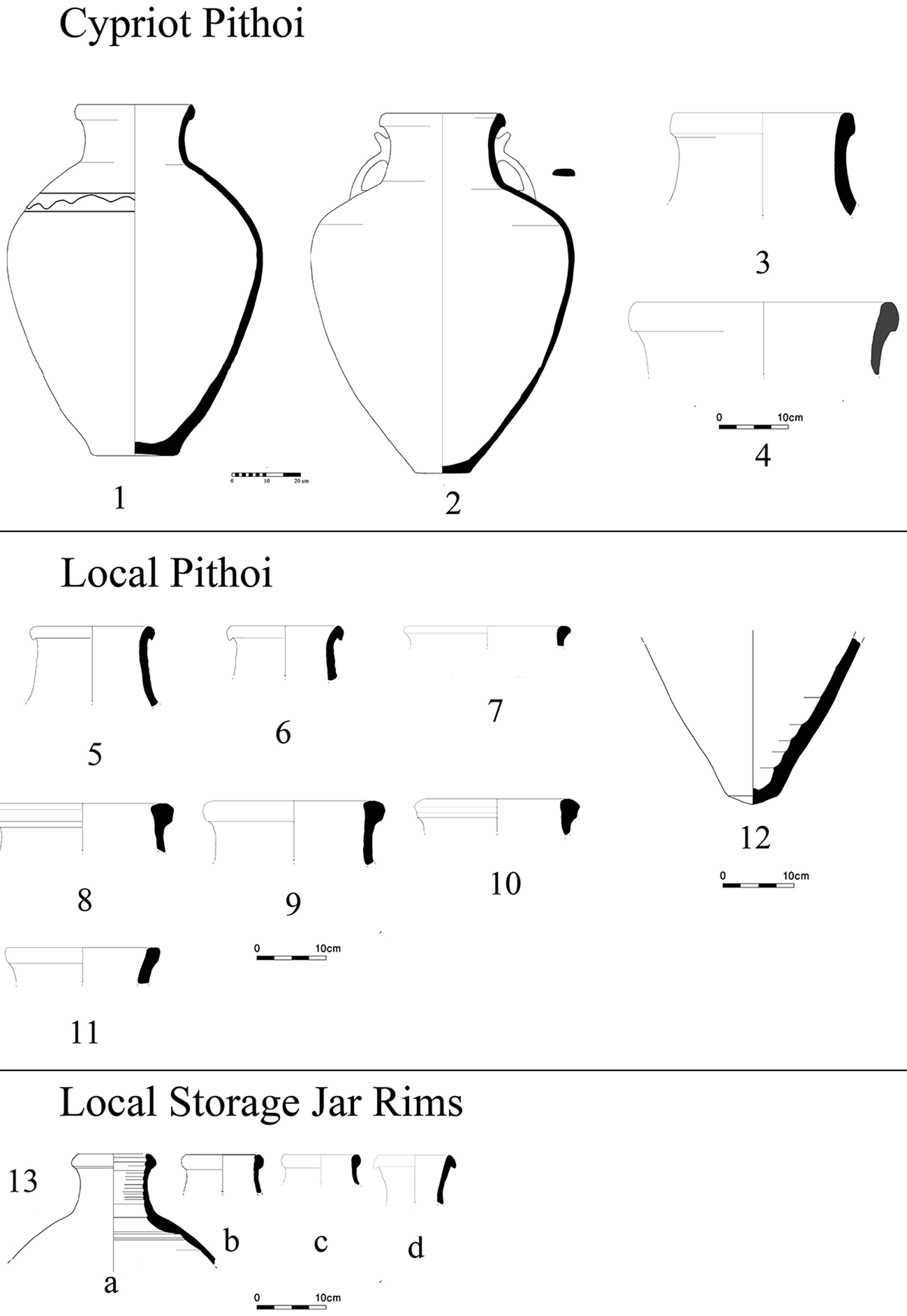

Two of the Cypriot pithoi were reconstructed in full (Fig. 3.1, 3.2), allowing for a robust typological and morphological analysis of their forms (Shai et al. Reference Shai, McKinny and Spigelman2019). These two (Pithos 432000 and Pithos 332081) were found in locus 33207 (Square NN7), with the bases having been placed inside the natural fissure of the bedrock. Due to their prominent location above the high bedrock, they would have been highly visible, possibly from afar. One other wavy-band style Cypriot pithos likely stood just north of the other two Cypriot pithoi near the northern wall of the enclosure (B1, L73406). While only body sherds were identified in the field, subsequently the rim was found by one of the authors (M.S.) when the material from Area B1 was being analysed in the lab in preparation for publication (Fig. 3.3). A nearly identical rim (Fig. 3.4) and associated body sherds were found about 7 m south-southeast of these pithoi (L83104, Square PP9).Footnote 13

Figure 3. LB Pithoi and storage jars from Area B1. Cypriot pithoi: (1) Pithos 432000 (NN7); (2) Pithos 332081 (NN7); (3) Pithos #734027 (NN6); (4) Pithos #831025 (PP9). Local pithoi: (5) Pithos #633005 (SS7); (6) Pithos #633011 (SS7); (7) Pithos #534028 (SS6); (8) Pithos #534025 (SS6); (9) Pithos #432018 (NN7); (10) Pithos #631061 (PP7); (11) Pithos #534002 (SS6); (12) Base of pithos #432018 (NN7); (13a–d) local storage jars.

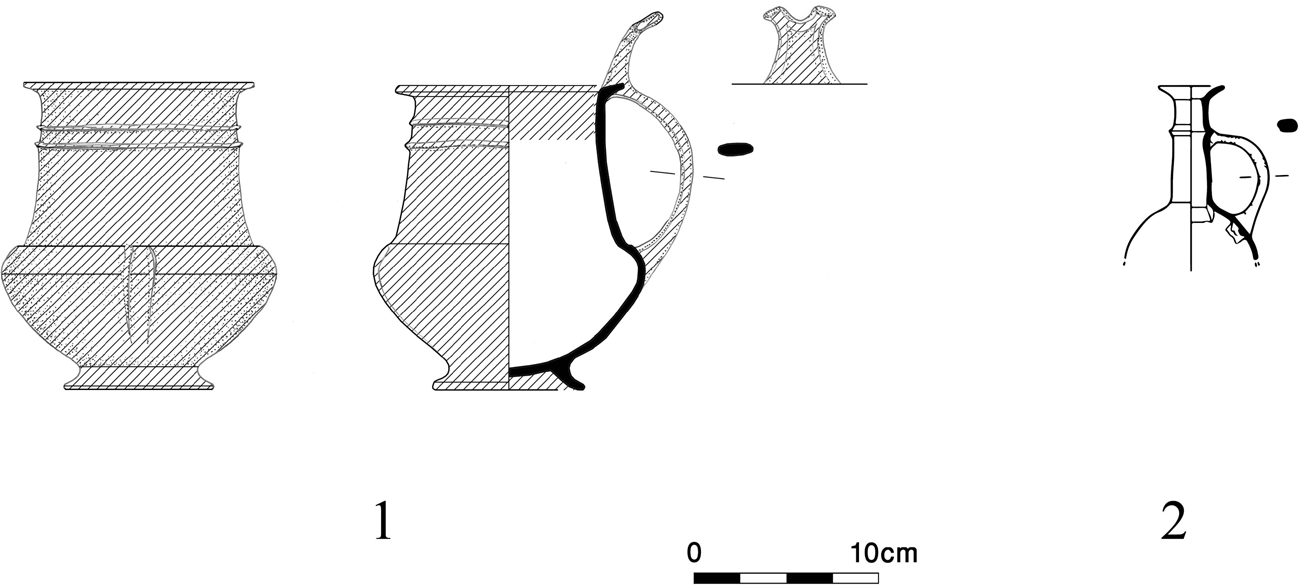

The two reconstructed pithoi show that, although the vessels were not identical, they seem to belong to the same general type (Shai et al. Reference Shai, McKinny and Spigelman2019, 67), sharing certain morphological traits; for example, the bases are flat and the rims are somewhat everted (not upright) and are thickened externally while also having a slight ‘gutter’ on the rim interior (see in particular Fig. 3.1). They also have similar rim diameters (c. 35 cm) and neck diameters (c. 26 cm). As reported elsewhere (Shai et al. Reference Shai, McKinny and Spigelman2019), residue analysis produced inconclusive details regarding organic contents that the pithoi may have contained. However, an additional piece of information potentially contributes to understanding how the pithoi may have been used in their final moments: pithos 332081 was found filled with stacked bowls (Fig. 4), and within pithos 432000, a complete tankard made of Base Ring I ware (Fig. 5.1) was yielded, in addition to a Base Ring I juglet (Fig. 5.2). While the bowls within pithos 332081 resemble local morphologies, petrographic studies on two samples showed they were actually made from clay originating further north along the Lebanese coast (Kleiman Reference Kleiman2020, 125, 147, 243), and thus, were imported to the site. It can therefore be concluded that the pithoi were storing small vessels, some of which were not local.

Figure 4. Bowls found stacked within a Cypriot pithos (332081), in situ, excavated as Locus 33204 in Square NN7. (Photograph: Chris McKinny.)

Figure 5. Cypriot vessels. (1) Cypriot tankard (Base Ring I), #332082; (2) Base Ring I juglet, #332045.

The distribution of the Cypriot pithoi shows they were all situated in the western portion of the courtyard, mainly around the high bedrock, with an additional one standing at the southwestern corner (Fig. 2).

The local pithoi

The local pithoi (Fig. 3.5–3.11) were concentrated further to the east, near the eastern extent of the courtyard (3 in SS6, 2 in SS7),Footnote 14 although two were recovered near the Cypriot pithoi: 1 immediately adjacent to the two Cypriot pithoi in NN7 and another a few metres to the east in PP7 near stone 63112, a possible standing stone.Footnote 15 At least one other pithos was found further south of the courtyard amongst local pottery.Footnote 16

Local pithoi were categorized as such based on a combination of the following factors: 1) they have very large rim and neck diameters; 2) their rims resemble local storage jar forms; 3) the vessels’ walls are significantly thicker than normal storage jars; 4) when preserved, their bases resemble local storage jar stump-base forms (Fig. 3.12); and 5) the vessels were made of local (not Cypriot) fabric. Factors 1 and 3, specifically, relate to the fact that these vessels are much larger than the site's typical storage jars. Factors 2 and 4 suggest that, although these vessels were much larger than local storage jars, certain aspects of those local jars (the rim typologies, form of the bases) were retained and reproduced. Factor 5 serves as an indication that these vessels were made locally.

In preparation of the final report for Area B1, a sample of 93 storage jar rims which were yielded from the same courtyard context as the pithoi had their rim and neck diameters measured. Based on these samples, the average rim diameter of Tel Burna's LB storage jars is 10.5 cm, while the average neck diameter is 8.3 cm (Fig. 3.13). Furthermore, the predominant base form of the Tel Burna storage jars is that of the stump-base type, typical for transport amphora of the period. Upon comparison to the local pithoi, one can clearly discern how much larger in size the group of vessels under investigation was. In fact, the local pithoi appear to fall into two different groups according to rim and neck diameters.

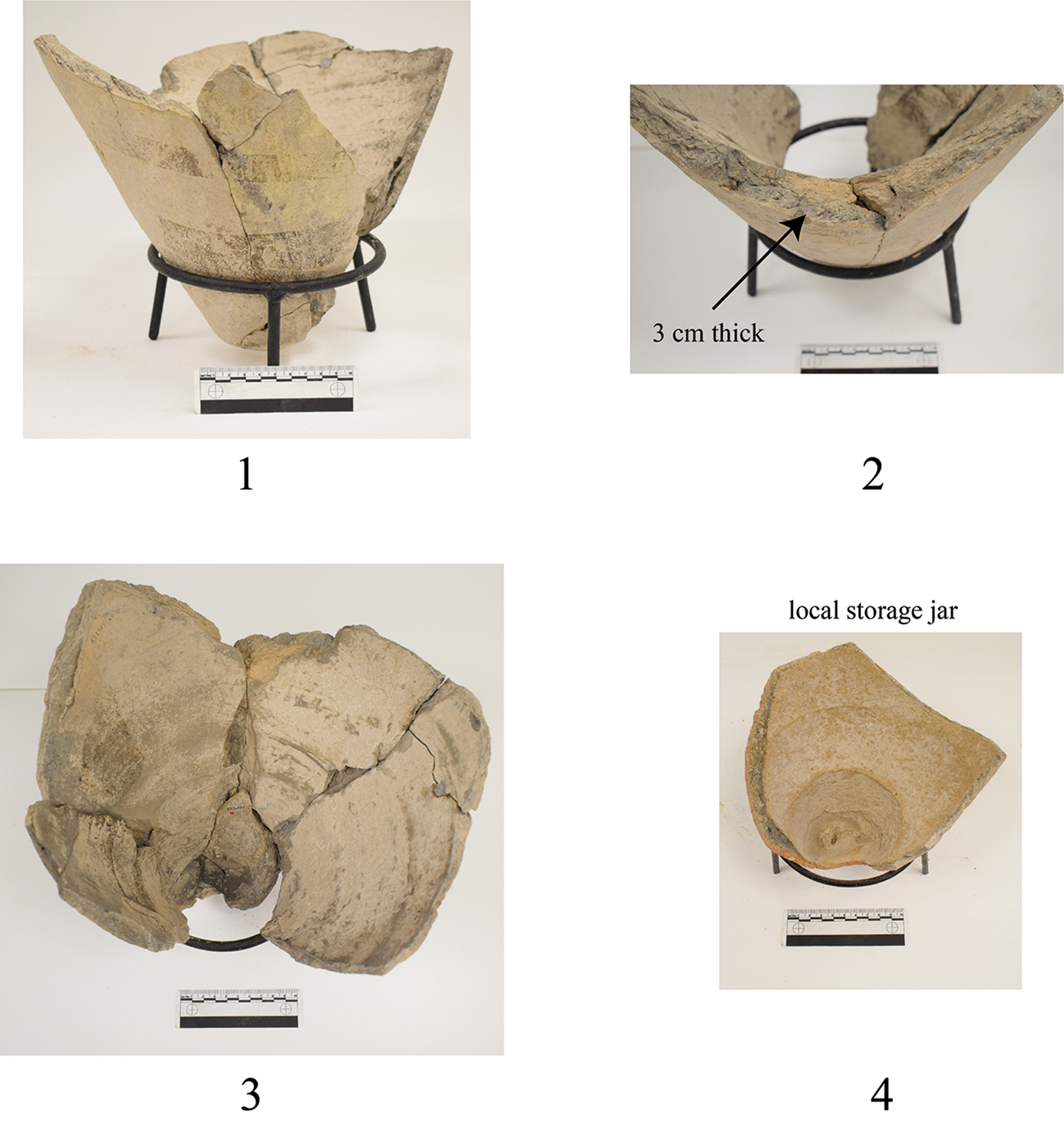

The pithoi from SS7 (Fig. 3.5–3.6) have rim diameters of 18.2 cm and 17.1 cm and neck diameters of 13.7 cm and 12 cm, respectively (633005 and 633011). A third pithos from further south has similar measurements (rim diameter is 17.2 cm, neck diameter is 12.5 cm). The other five pithos rims are all over 20 cm. Most significantly was a large pithos (Fig. 3.9; pithos 432018, Square NN7) found alongside the two Cypriot pithoi: its rim diameter is 26.6 cm and its internal neck diameter is 20 cm. The bulbous and upright form of the rim is that of the typical storage jar rim from the site, but larger. Moreover, its base is of the local storage jar stump-base type, but significantly thicker than the other stump bases from the site (Figs. 3.12, 6.1). In fact, technologically, a similar process was implemented in the forming of the bases and the bodies of the local storage jars and the locally made pithoi: an amorphous protruding blob of clay on the base interiors indicates the same procedure of the potter closing the base (see, for example, in Panitz-Cohen Reference Panitz-Cohen, Panitz-Cohen and Mazar2006, 79–80); and bands are visible in the wall interiors of both vessel types where coils were joined (Fig. 6.3–6.4). These observations indicate a similar process of production. The wall thickness of pithos body sherds varied, but was visibly thicker than standard storage jar wall thickness, measuring up to 3.2 cm (Fig. 6.2), compared to storage jars which range around 0.6–0.8 cm.

Figure 6. Local pithos base (1–3) and storage jar base (4). Note the thickness of wall in 2. Compare interior coiling of 3 and 4, and the remains of amorphous clay blob in the middle of the pithos and jar base interiors.

It should also be pointed out that some of the local pithos sherds have equally spaced, parallel concentric striations on the outer face, a phenomenon regularly observed on local pottery.Footnote 17 Additionally, although generally undecorated, one pithos is decorated with an incised wavy band; however, in contrast to the Cypriot tradition, it is vertical, not horizontal (Fig. 7.1).

Figure 7. (1) Restored local pithos from Tel Burna, Area B, with morphology resembling earlier MB pithoi; (2) An incised vertical wavy band decoration. Note the concentric striations. (Photograph: Benjamin Yang.)

Reviewing these data, it appears that some of the pithos rims resemble local forms from earlier periods (e.g. see the MB pithoi at Tel Kabri: Yasur-Landau et al. Reference Yasur-Landau, Cline and Koh2018, 317–21),Footnote 18 while the group of larger rims which were over double the size of the average local storage jar appear to conceptually be more along the lines of the enormous Cypriot pithoi—in terms of their large diameters. As noted, the rim forms and the bases, however, resemble local storage jar rims and bases, not those of the Cypriot vessels, and the one restored pithos does not morphologically resemble the Cypriot pithoi, but rather is more in line with earlier pithos traditions of the MB (Fig. 7.2).

Distribution

The overall distribution of the pithoi should be noted (see Figure 2). The Cypriot pithoi were concentrated in a highly visible location in the western part of the courtyard, and as published elsewhere, in association with many other special vessels and objects (Shai et al. Reference Shai, McKinny and Uziel2015). The local pithoi, on the other hand, were concentrated mainly to the east, in association with more mundane materials (mainly storage vessels, cooking pots and bowls; a tabun; with few vessels of special nature). There also seems to be a point of intersection where two of the larger locally produced pithoi were situated in close proximity to the Cypriot pithoi.

Discussion

The data on Tel Burna's pithoi will now be discussed in terms of object biographies, agency and related concepts in order to explore how human interaction with foreign materials can impact local practices and traditions. The importation of foreign vessels and their installation at an important and highly visible part of a multifunctional enclosure signals both an encounter with foreign traditions and the integration of a new type into local customs. Moreover, it is argued here that the presence of imported Cypriot pithoi at the site was intricately related to the process of local potters producing pithoi according to recognizably local morphologies (more below).

The following discussion focuses on 1) the effects the new context had upon the imported Cypriot pithoi (i.e. human agents manipulated and altered object biographies and functionality); and 2) how the encounter between local inhabitants and foreign commodities had an impact on the locals themselves (i.e. the human–object network was altered and adapted as a new object form was integrated into the network). Perhaps the local potters’ response to this encounter (i.e. the production of new vessels) can be viewed as expressions of identity negotiation.

Cypriot pithoi: biographies and recontextualization

As discussed above, much like humans, objects carry with them biographies. Sometimes these biographies are more predictable than others: for example, when an object produced for a specific purpose gets used throughout its ‘lifetime’ for that said specific purpose (e.g. a cereal bowl gets used for eating cereal). The material remains from Tel Burna suggest a much more complex situation.

In general, it is widely acknowledged that Cypriot pithoi primarily functioned as long-term and short-term storage vessels used for storing produce or liquids (Keswani Reference Keswani, South, Russel and Keswani1989; Knapp & Demesticha Reference Knapp and Demesticha2017, 88; Pilides Reference Pilides2000; Reference Pilides, Karageorghis, Matthäus and Rogge2005, 171).Footnote 19 On Cyprus, these vessels have been found in various settlement contexts such as households, elite residences, workshops and large-scale administrative buildings (e.g. Keswani Reference Keswani and Hein2009; Pilides Reference Pilides2000), often set or sunk into floors (e.g. Pilides Reference Pilides2000, 15–16, 34). During the LB, Cypriot pithoi began to play a role in the domain of long-distance exchange, when it is well documented that they were occasionally used in maritime transport to ship various commodities throughout the eastern Mediterranean (Keswani Reference Keswani and Hein2009, 107, fn. 1; Knapp Reference Knapp2018a, 148).Footnote 20 In fact, one of the Cypriot pithoi from the Uluburun shipwreck was used to store and transport smaller Cypriot vessels, including White Slip II and Base Ring bowls, among other forms (Knapp & Demesticha Reference Knapp and Demesticha2017, 90). It therefore appears that while Cypriot pithoi were not specifically manufactured or well designed for seaborne transportation (Knapp & Demesticha Reference Knapp and Demesticha2017, 89), they could be used in maritime trade when market conditions were favourable—such as during the period of interconnected maritime networks of the LB.

Although the original functions, or original intended functions, of Tel Burna's Cypriot pithoi cannot be positively discerned, they were in all probability used for storage of produce within a local Cypriot context. One wonders whether the fact that one pithos has two handles, while the others are handleless, may be an indication of different intended uses altogether. Regardless, it seems likely that they were not originally intended by their makers to end up at an inland Levantine site serving some form of ceremonial function (Shai et al. Reference Shai, McKinny and Uziel2015).Footnote 21 Indeed, in addition to the pithoi being in a permanent and visible place, associated finds from the vicinity include decorated goblets, a decorated krater, ceramic masks, zoomorphic figurines and many Cypriot imports (some of which are very rare), thus underscoring the special, ceremonial nature of the context.

Accordingly, while pithoi were primarily used for stationary storage and were not easily movable,Footnote 22 when the circumstances were suitable, they had the potential to be used as ‘transportable vessels’ (although not as mobile as the smaller transport amphora of the period).Footnote 23 The biographies of Cypriot pithoi were therefore dynamic, responsive to their specific circumstances. In fact, while it is generally assumed that upon arriving at their destination most of these pithoi remained on their ships for storing and transporting other commodities (Knapp & Demesticha Reference Knapp and Demesticha2017, 93), those found at Tel Burna clearly had a divergent story. Whatever the reason for transporting the Cypriot pithoi from the sea to this inland site,Footnote 24 upon arrival at Tel Burna, the pithoi—unaltered in form—were recontextualized. They were given a new meaning within their new context, and accordingly, the vessels were transformed into permanent and highly visible installations, set into the floor in an open public space.

This recontextualization of foreign objects created a new material reality for the local social group. With the introduction and integration of Cypriot pithoi into the Tel Burna landscape, the human–object network evolved and became more complex as the knowledge of what types of things exist in the world was altered. The result was that the encounter between the Cypriot pithoi and the inland inhabitants of Tel Burna created a state of entanglement (e.g. Stockhammer Reference Stockhammer2012), the type of relationship discussed above in which foreign objects can influence humans to modify their social practices.Footnote 25 The inhabitants from Tel Burna, based on the things and practices they knew of within their local environment, therefore turned the Cypriot pithoi into something other than what the pithoi previously were; the pithoi were given new life trajectories that diverged from their biographies up until their arrival at the site. There certainly was a southern Levantine predisposition of associating large vessels with the potential to serve as permanent fixtures for storage. While in a sense this is not far removed from the original Cypriot functions, at Tel Burna the pithoi were no longer ‘transport vessels’, nor were they simply used for storing local produce; now, they were permanently installed in a public, highly visible location within a ceremonial context, to be viewed as exotic with connotations of luxury (see Van Wijngaarden Reference Van Wijngaarden, Maran and Stockhammer2012, 63). This recalls, for example, the redefined function of imported Mycenaean kraters found in southern Levantine contexts—unaltered in form but provided with a new use and social meaning (Stockhammer Reference Stockhammer2012, 25).

As argued above, the integration of new objects into the local repertoire of things has the potential to precipitate new ideas and can lead to producing new material forms. It is suggested that displaying the Cypriot pithoi in a highly visible and communal context had a fundamental impact on social actors at the site and is directly connected to the production of the local pithoi. The exotic nature and prestige of the imported pithoi would have captivated a population unfamiliar with such vessels. The objects themselves therefore impacted the people—they produced agency. In some instances, the presence of exotic goods elicits a desire amongst the viewers to acquire more of that exotic commodity.Footnote 26 The case at Tel Burna, however, is different. The encounter with foreign goods educed local potters to go to action and produce new objects, the local pithoi (more below). Object agency has become a real factor.

Imitations and the imported and local pithoi from Tel Burna

In terms of material culture, the impact of foreign objects on local customs can often be identified within the material record when imitations are encountered. The human behaviour of producing objects that mimic other forms is quite common and serves as an indication of the importance and perceived value of the object being mimicked.Footnote 27 Numerous examples of imitations throughout the ancient Mediterranean demonstrate the cross-cultural nature of this phenomenon.Footnote 28 Specifically during the LB in the southern Levant, local imitations of foreign forms were well attested and include imitations of Cypriot, Mycenaean and Egyptian imports (Amiran Reference Amiran1970, 182–8; Bergoffen Reference Bergoffen, Czerny, Hein, Hunger, Melman and Schwab2006; Martin Reference Martin2011; Van Wijngaarden Reference Van Wijngaarden, Maran and Stockhammer2012, 63). Within the Cypriot repertoire, the prevalent imitations are of White Slip II bowls and Base Ring jugs and juglets; these imitations generally mimic the original form of the vessels, although they are manufactured with local clay and techniques (e.g. use of wheel versus by hand; Amiran Reference Amiran1970, 182). Sometimes local decorations were added as well. This demonstrates that at a fundamental level, the importation of foreign items impacted the local landscape not only by serving as exotic goods and symbols of prestige, but by actually imprinting foreign material concepts upon the local ceramic repertoire.

Regarding pithoi, in only a few cases have LB pithoi that were produced in and imported from Cyprus been found in the Levant (Shai et al. Reference Shai, McKinny and Spigelman2019, 77–8; Shalvi et al. Reference Shalvi, Bar, Shoval and Gilboa2019, 129–30, 136), and these mainly from Ugarit and Minet el-Beida.Footnote 29 The fact that at least four made their way to Tel Burna is quite remarkable in this light. Furthermore, imitations of Cypriot pithoi in which potters in the southern Levant used local clay to make pithoi mimicking the morphology of the Cypriot forms have occasionally been found, but in general were rare (e.g. at Tel Esur; Shalvi et al. Reference Shalvi, Bar, Shoval and Gilboa2019).

In contrast to the examples of imitations discussed above, it appears that at Tel Burna, while the local potters were, in a way, making imitations of the Cypriot pithoi, these imitations were not intended to mimic the form, but rather, the concept. They reinterpreted the form to produce items according to the local way of doing things. As observed above, the locally produced pithoi resembled the forms and morphologies of local storage jars, just much larger. They also display ceramic techniques evident in local storage-jar production (e.g. base formation, concentric striations), and the decorated sherd—a single vertical wavy band—suggests a local potter was aware of the Cypriot horizontal wavy bands but executed it in a different manner.

Becoming entangled with the Cypriot pithoi on site, the local potters were captivated by something new; their material surroundings and relational network with things expanded, causing their mental template of a ceramic repertoire to include the production of pithoi.Footnote 30 In this way, one can perceive that local identities and practices were altered, or adapted, via the encounter with the foreign objects. Following Ingold, the makers of things (here, potters) are not separate from their material surroundings; they are participants within it. The new things (the Cypriot pithoi) introduced into the world of the maker open up the potential for the maker to create new forms (local pithoi). It seems the local potters were not simply engaging in new productive practices, though; they were actively navigating a new identity (at least, with a new understanding of the material world) since the production of the new material form was not strictly mimicking the foreign form, but was of local morphology. In other words, the idea of the Cypriot pithoi was not adopted to make exact imitations; rather, it was adapted to produce a similar conceptual object, but according to local normative forms.

Revisiting the human–object relational interactions at Tel Burna

A dynamic picture of human–object interactions at Tel Burna has therefore emerged, and specifically in Locus 33207, there is a palpable convergence of concepts such as object biographies, agency, captivation, entanglement, and processes of making things. Tracing the unique pithos biographies enables a series of dynamic human–object relationships to be discerned. A suggested chain of relational interactions is as follows. During the LB, there was a substantial amount of international interconnectivity throughout the eastern Mediterranean. Large quantities of imported vessels appear during this period at sites throughout the southern Levant. At Tel Burna, this is true as well, where 1–2 per cent of the overall LB assemblage was composed of Cypriot imports (mainly White Slip II and Base Ring II).

These interactions with the maritime trade networks led to a number of Cypriot pithoi arriving at the site of Tel Burna at some point during the LB II, the reasons unclear. Pithoi, like other vessels, have the potential to be used in different ways (storage, transport). Upon arrival at Tel Burna, they were placed in a prominent location above the high bedrock. While their previous context as cargo had them placed out of sight and used essentially for transporting commodities, their new context transformed them into viewable and permanent fixtures, perhaps as prized objects to be showcased or possibly to be used for storage or depositing various organic or inorganic commodities within a ceremonial setting. As noted above, at least two of the Cypriot pithoi were found with other vessels inside them, including local bowls, bowls likely imported from the Lebanese coast, and an imported Cypriot tankard and juglet, both of Base Ring I ware. The latter observation is quite striking, as Base Ring I ware was generally circulated at a date earlier than the thirteenth-century occupation at Tel Burna, and thus signifies these were viewed as valuable objects that were kept for an extensive period of time. This indicates that, although the pithoi were recontextualized with a new function and meaning, there still remained some memory (perhaps coincidental) that they could be used for storing smaller vessels, and at least in their final moments, as receptacles for depositing exotic, even imported, goods.

It follows that while the pithoi were recontextualized by the inhabitants of Tel Burna, the vessels themselves, being placed on display,Footnote 31 captivated locals and impacted their traditions. This is evident in the appearance of locally produced pithoi at the site, precisely during a period when large pithoi are largely absent from sites in the southern Levant. Yet, these were not mere imitations. While the Cypriot pithoi may have captivated local potters of the site and served as a stimulus to produce pithoi of their own, the potters themselves did not respond by mimicking the morphology of the imported forms, but rather, maintained an adherence to the ceramic forms and techniques with which they were more familiar.

When considering the distribution of the finds within the courtyard, a most interesting pattern is observed. Looking solely at the pithoi, there is a clear division between ‘local’ and ‘foreign’ within two different functional contexts: the Cypriot pithoi were all concentrated on the high bedrock in the most important and special part of the courtyard—associated with many special and exotic objects and a perforated stone 63112—while the local pithoi were mainly concentrated on the eastern side of the courtyard where the assemblage appears much more mundane in nature (serving functional, not symbolic, purposes).Footnote 32 Perhaps this was an expression of the efforts of the site's inhabitants to maintain a sense of controlled distinction as they navigated their evolving identities and changing understandings of the material world around them. Yet, when considering the courtyard assemblage as a whole, Locus 33207 has the appearance of a small microcosm of the international interconnectivity of the period, displaying an intermingling of concepts of ‘foreign’ and ‘local’. Imports were in use alongside local types, highly integrated into the typical LB repertoire of things. Most of these foreign objects may ultimately not have been truly perceived as foreign or exotic as much as regular parts of the LB Levantine material reality. However, the rarity of the Cypriot pithoi left a different imprint on the Levantine population, not only captivating them, but consequentially producing agency and the circumstances within which local makers were inspired to make new things.

Conclusions

This paper set out to investigate how objects can impact the way humans behave, compel them to alter certain practices and, under certain circumstances, lead them to generate new types of things. Within the dynamics of human–object networks, it has been argued that objects can produce some form of agency. If the Cypriot pithoi had not been brought to Tel Burna, it seems very unlikely that local potters at the site would have produced pithoi of their own. Yet this form of agency cannot solely be considered an extension of the objects’ makers. No matter what intention the Cypriot potters may have had for their product, it is difficult to imagine a scenario in which they had in mind that not only would the pithoi be moved from a ship to an inland Levantine site, but that the interaction between the Cypriot pithoi and the local inhabitants of the Levant would subsequently have compelled the local potters to produce conceptual imitations of those very vessels.

Thus, the application of the concepts of object biographies and object agency has proven to be especially constructive for the analysis of the Tel Burna pithoi. Humans and things are indeed in a dynamic relationship with one another; both impact one another. As this study has shown, while objects have biographies, their biographies may ultimately be disassociated from whatever intentions the original maker may have had. As objects are moved about and recontextualized, coming into contact with new objects in new scenarios, unpredictable results can occur. Under the right conditions, agency can be produced. These lessons can be of utility to archaeologists focusing on regions throughout the world. As a discipline, we regularly investigate the relationship between people and things. Furthermore, it is quite common for people to encounter new things, and as shown here, these new relationships can produce different outcomes. In some cases, foreign objects become associated with prestige, while in other situations, they intrigue people to make imitations. At Tel Burna, they did something different: they inspired local potters to use the concept of a Cypriot pithos, but to produce pithoi in morphological accordance with the local normative forms.

Acknowledgements

The excavations of Tel Burna are supported by an Israel Science Foundation grant (grant no. 257/19, I.S.). M.S. would like to thank Prof. A. Bernard Knapp for his kind guidance by providing some of his insights—and a robust bibliography—on the theoretical and Cypriot aspects of this study. We are also very grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their constructive feedback and critical comments which unquestionably improved the overall quality and clarity of the article and its arguments.