Introduction

There is a great duality to the humble human hand in rock art. In one way, it is deeply personal, a kind of memorialization of the individual. Yet in another way it is one of the very few ‘universal symbols’ in rock art, being found in many parts of the world, spanning vast time periods and cultural contexts, representing our shared humanity. The human hand has been added to rock surfaces in Australia for tens of thousands of years, primarily in the form of prints and, more commonly, stencils which seem to appear in the earliest as well as the more recent rock-art traditions (e.g. Chaloupka Reference Chaloupka1993; Layton Reference Layton1992; Morwood Reference Morwood2002; Veth et al. Reference Veth, Myers, Heaney and Ouzman2018). While rock-art styles and certain depicted subject matter came and went, the human hand figure held its ground. Then, sometime during the late nineteenth or early twentieth century in the midst of dramatic changes to Aboriginal life in western Arnhem Land, something changed. While the standard hand stencilling continued as before, a new style of highly decorated and elaborated hand figures emerged and multiplied for a short period of time—the Painted Hand style (Fig. 1). In this paper, we explore these changes and the possible motivations behind them.

Figure 1. One of the Painted Hands at Awunbarna. (Photograph: Paul S.C. Taçon, 2018.)

Artefacts have the remarkable ability to not only reflect periods of stress within and between different societies, but to also play an active role in assisting these groups actively to navigate these experiences. As Hodder (Reference Hodder1979, 450) suggests, ‘When tensions exist between groups, specific artifacts may be used as part of the expression of within-group corporateness and “belongingness” in reference to outsiders’. If we accept the premise that, in times of stress, we may see an increase in the production of symbols of identity, then it follows that sudden, obvious shifts in style evidenced in the archaeological record may indicate such traumatic episodes.

In this paper, we argue that a new style of rock art (Painted Hands) emerged in response to contact, and specifically to changes occurring in Aboriginal life as a result of new interactions in the historical period. This suggests that the Painted Hands are more than simply hand stencils or markers of individuality (Fig. 1). As we will argue and demonstrate, they represent stylized and intensely encoded motifs with the power to communicate a high level of personal, clan and ceremonial identity at a time when all aspects of Aboriginal cultural identity were under threat.

Innovation in rock art

This study builds upon the vast literature surrounding archaeology, art and the impetus for change. For example, Wiessner (Reference Wiessner1983) argues that situations likely to invoke a strong sense of group identity are those where people are fearful, where there is inter-group competition, or situations where there is a need for co-operation to attain social or political or economic goals. Colonialism, invasion, dispossession and war dominate such discussions (e.g. Dowson Reference Dowson1994; Troncoso & Vergara Reference Troncoso and Vergara2013).

Patricia Crown's (Reference Crown1994) study of the emergence of polychrome Salado pottery in the American southwest during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries ad offers a somewhat contrasting but still related example. This period saw considerable migration events, possibly due to warfare and drought, leading to the breakdown of kin networks and associated ritual structures. She argues that the polychrome decorative tradition emerged as part of a broader hybrid identity, perhaps consciously adopted by migrants as a strategy to develop worthwhile materials or skills in order to fit better into new communities and supplement farming as a source of subsistence, since farm land available to migrants was probably poor (Crown Reference Crown1994, 213). In other words, in a context of demographic pressure and cultural breakdown, new styles were operationalized to promote peaceful co-existence among newly adjacent populations.

Innovation in an archaeological context, like our Painted Hands, is regularly framed as a quasi-automatic, functionalist or evolutionary process through which less efficient or adapted materials, ideas or technological systems are replaced by more efficient or better suited ones. However, this process is actually deeply embedded in social interactions and tied to larger social and material spheres (Bijker Reference Bijker1995; Lemonnier Reference Lemonnier1992; Pfaffenberger Reference Pfaffenberger1992; Rogers Reference Rogers2003; Torrence & van der Leeuw Reference Torrence, van der Leeuw, van der Leeuw and Torrence1989). Not only is the impulse to innovate or to accept an innovation socially conditioned, but the desire for a new object, practice or technology develops out of a pre-existing process of learning about and testing it (Rogers Reference Rogers2003; Rogers & Shoemaker Reference Rogers and Shoemaker1971).

The emergence of new rock-art styles in western Arnhem Land has commonly been associated with changes in environmental conditions. This is most obvious in the overarching chronology developed by George Chaloupka (Reference Chaloupka1993), who directly links rock-art styles to environmental transformations (for example, X-ray art is placed within the Freshwater period, Dynamic Figure rock art within the Pre-estuarine). Indeed, archaeologist Rhys Jones suggested in the 1980s that competition for resources led to an increased marking of territory and differentiation between groups evident in aspects of cultural life (Jones Reference Jones and Jones1985, 293–4).

Of the more recent rock art, Chaloupka (Reference Chaloupka and Jones1985) and Jones (Reference Jones and Jones1985, 291–4) argue that Complex X-Ray rock art was produced as a response to an increase in population size which itself was the result of environmental change. Over the last two decades, demographic pressure has become a central focus of evolutionary archaeological models of innovation and technological change (e.g. French Reference French2016; Powell et al. Reference Powell, Shennan and Thomas2009; Shennan Reference Shennan2001). These models view increasing population size and connectivity as key causal factors in the development of new and more complex technologies, which themselves are understood to help human populations relieve and respond to demographic pressure and environmental constraints. As June Ross (Reference Ross2013, 165) notes in her pan-Australian study of regionally distinct rock-art styles, ‘alterations noted in the archaeological record such as the introduction of a new art style are viewed as adaptive strategies aimed at ameliorating changing ecological conditions’. These models have, however, come under increasingly heated critique, particularly from Australian archaeologists, as many are premised on outdated and colonialist understandings of Aboriginal Australian (and particularly Tasmanian) society and material culture (Collard et al. Reference Collard, Vaesen, Cosgrove and Roebroeks2016; Frieman Reference Friemanin prep; Henrich Reference Henrich2004; Vaesen et al. Reference Vaesen, Collard, Cosgrove and Roebroeks2016).

Indeed, Ross (Reference Ross2013, 165) also suggests there is more to this story than just adaptation to environmental change. She argues that:

each of the varied art assemblages were introduced at a time when the relationship between people and place was under pressure, whether the pressure came from outside intruders, rising sea levels, population increase or the introduction of more intense interaction in the form of trade networks, or a combination of these factors.

Likewise, others, such as Bruno David and colleagues (David & Chant Reference David and Chant1995; David & Lourandos Reference David and Lourandos1998; Reference David and Lourandos1999) have also argued for a primarily socio-cultural context influencing change in the archaeological record.

How, then, may this be reflected in rock art produced during the recent past in Australia? Colonialism impacted upon existing rock-art traditions Australia-wide in various ways. Some groups were so impacted by violence, incursions into their land and forced movement that they all but ceased rock-art production (Mulvaney Reference Mulvaney2018; Taçon et al. Reference Taçon, Paterson, Ross and May2012, 428), while others were drawn to connect with their rock-art traditions in new ways, such as by re-working earlier rock-art imagery (Taçon et al. Reference Taçon, Kelleher, King, Brennan, Domingo Sanz, Fiore and May2008). Still others engaged with the new subject matter, depicting introduced material culture and animals, as though reflecting on its significance (May et al. Reference May, Wesley, Goldhahn, Litster and Manera2017b); while, at the same time, they continued to produce more traditional motifs long after the novelty of these new subjects had run its course in rock art (Frieman & May Reference Frieman and May2019; May et al. Reference May, Taçon, Guse and Travers2010; Reference May, Maralngurra and Johnston2019).

Despite the evident capacity of Australian rock art to reflect major changes—both social and environmental—impacting on human society, the production of rock art is typically discussed in the context of the maintenance of traditional practices with emphasis on the continuity of long-term trends (i.e. Chaloupka Reference Chaloupka1993). In fact, as recent research on contact rock art has shown (see Goldhahn & May Reference Goldhahn and May2019 for an overview) and as argued by Frieman and May (Reference Frieman and May2019), Australian historical-period rock art reveals a dynamic, socially embedded series of practices which allowed new ideas, new materials and new ways of seeing the world to be examined, interrogated and selectively adopted into pre-existing social structures and practices.

The Painted Hands of western Arnhem Land

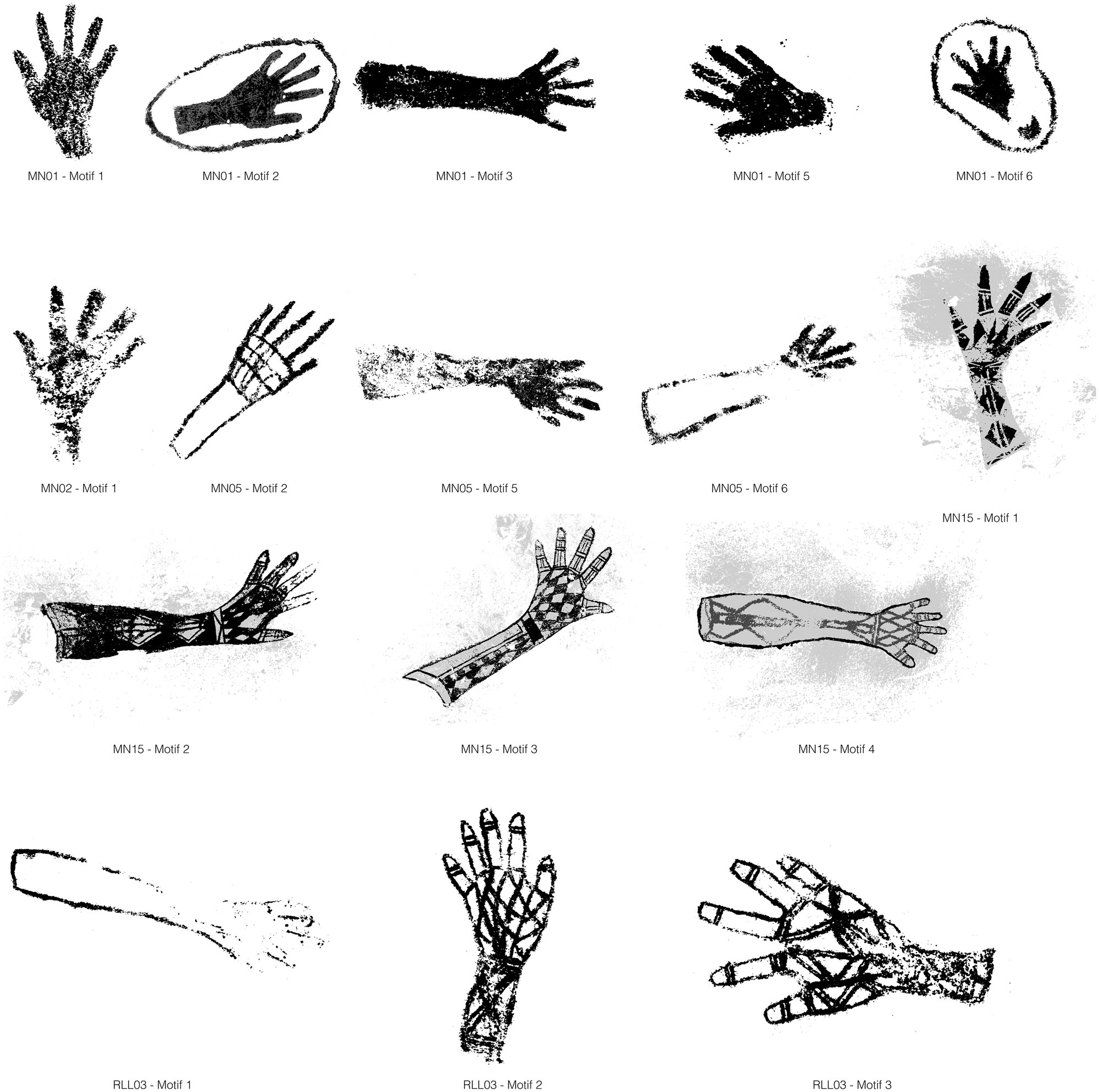

Painted Hand rock art has attracted the attention of researchers for some time due to its vividness at particular sites. Many Painted Hands have complex design elements not seen in other rock art. For this study, we define Painted Hand rock art as:

• The representation of an anatomically correct human hand, wrist and, sometimes, forearm by stencil, outlining or painting of the shape.

• These figures are then infilled with painted design features of varying complexity (e.g. Figs. 1 and 2).

• Some figures are also encircled by a line (e.g. Figs. 1 and 3).

Figure 2. Digital tracings of some of the Painted Hands from Minjnymirnjdawabu. (Photographs: Tristen Jones. Tracings: Meg Walker.)

Figure 3. Examples of encircled Painted Hands from Awunbarna. (Photographs: (left) Paul S.C. Taçon, 2018; (right) Sally K. May, 2019.)

Previous research

Painted Hands often feature in illustrations relating to western Arnhem Land rock art (e.g. Brandl Reference Brandl1973, 169, fig. 63; Mountford Reference Mountford1956, 178, pl. 48), but have rarely been the topic of any deeper analysis. We focus here on the authors who attempted to interpret this unique rock art, rather than the many times Painted Hand figures were used for illustrative purposes only.

Jan Jelínek deserves special mention for his documentation of many Painted Hands and brief discussions of them in his many publications relating to Arnhem Land (e.g. Jelínek Reference Jelínek1976; Reference Jelínek1977; Reference Jelínek1989). Yet it was George Chaloupka (Reference Chaloupka1993) who offered the first detailed interpretation of their emergence. He also defined their geographical distribution, arguing that they were found from ‘the northern outliers of the Wellington Range at the base of the Cobourg Peninsula to the Oenpelli and Ubirr-Canon Hill region, with occasional individual representations being found elsewhere along the northern and western margins of the plateau’ (Chaloupka Reference Chaloupka1993, 214). In terms of clan lands, he states they are found predominantly in the estates of the Amurdak-speaking groups, who had ritual ties to the Iwaidja and Garrig people to the north on the Cobourg Peninsula.

Chaloupka argues that this type of rock art was originally inspired by the gloves worn by European women at the Victoria Settlement in the early 1800s. He claims that he was told this by Galardju elder Namadbarra (Paddy Compass Namatbara) (Chaloupka Reference Chaloupka1993, 214). Variations in the design elements were argued to reflect the design of the original glove with some featuring ‘lace-like quality’ and others representing ‘pieces of leather forming a glove’. In other cases, he argues the designs represent the anatomy of the actual hands with life-lines and nails depicted (Chaloupka Reference Chaloupka1993, 214).

Tellingly, Roberts and Parker (Reference Roberts and Parker2003) do not reiterate this interpretation in their book focusing on the rock art of Awunbarna (Mt Borradaile), the area Chaloupka (Reference Chaloupka1993, 214) suggests is the epicentre for this type of painting. Instead, they present photographs of key examples of the main shelters where Painted Hand figures occur and offer occasional information on their design. For example, in the caption to one photograph they state:

Decorated hand stencils, one with Reckitt's Blue, overlying layers of figurative art in the Major Art habitation shelter. A number of the hand stencils have borders around them in what is possibly an attempt to distinguish them from their immediate environment. Unusually, the hand stencil on the bottom left has two borders around it. (Roberts & Parker Reference Roberts and Parker2003, 32)

They offer no further attempt at interpretation. Their use of the term ‘frame’ in the caption to another photograph (Roberts & Parker Reference Roberts and Parker2003, 33) is perhaps inspired by Chaloupka's (Reference Chaloupka1993, 214) discussion of this design element, where he argues that this design feature focuses attention on the image, just as a European picture frame would, and that the artists may have been inspired by framed pictures seen at nearby settlements. Furthermore, Chaloupka (Reference Chaloupka1993, 214) suggests that the frame may compensate for the loss of the ‘distinguishing contours’ of the artist's hand as the stencils were infilled with design elements. The frame, he argues, could be an attempt to retain individual identity and ‘emphasised the artist's presence and identified his work’ (Chaloupka Reference Chaloupka1993, 214).

It is worth noting that a number of researchers have associated the Painted Hands with broader styles. This includes ‘Complex x-ray’ (Brandl Reference Brandl1973, 168–9), ‘Decorative X-ray’ (e.g. Chaloupka Reference Chaloupka1983, 14) and ‘X-ray II’ (Haskovec & Sullivan Reference Haskovec and Sullivan1986, 30). Chaloupka (Reference Chaloupka1983, 13) suggests that the Decorative X-ray style followed the Descriptive X-ray style, moving away from a focus on internal elements of the subject-matter and more towards ‘decorative expression’ (see also Haskovec & Sullivan Reference Haskovec and Sullivan1986, 29). As discussed below, we do not believe the Painted Hands incorporate X-ray design elements and we therefore argue that they have been misplaced in these broader stylistic categories.

Paul S.C. Taçon recorded a fascinating discussion with Bill Neidji regarding Painted Hands during his 1980s fieldwork. He states that ‘Some stencils have been painted with clan designs and x-ray features, such as finger bones, to produce striking images by which to honour and remember particular individuals’ (Taçon Reference Taçon1989a, 138). Neidji informed him that after people die their spirits watch over their ‘finger prints’ (hand or hand-arm stencils); and, if someone paints the stencils, the spirits will say you are a good man. Likewise, if someone were to rub the stencil off the wall, the spirit might make you sick (Taçon Reference Taçon1989a, 138). As discussed below, Neidji himself was responsible for the design elements within an existing hand and arm stencil made at Amarrkanangka (Cannon Hill) in the 1930s (Taçon Reference Taçon1989b, 25, fig. 34).

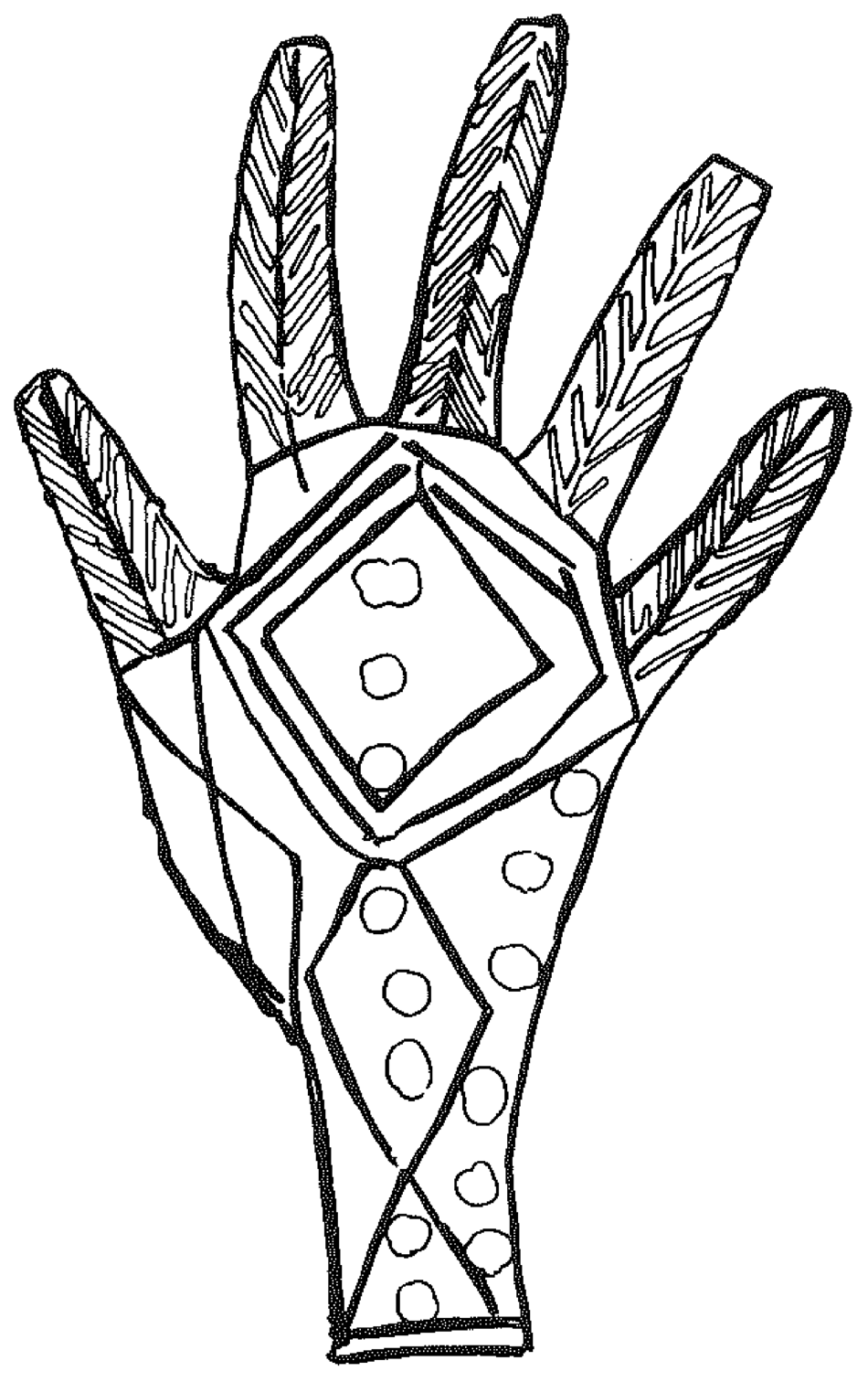

Charles Mountford, visiting in 1948, also describes a stencil of the hand of a small girl who had since died at Amarrkanangka (Fig. 4). He states that ‘It has been decorated with attractive herring-bone designs’ (Mountford Reference Mountford1956, 178, pl. 48G). While it is unclear if the designs were added later, it does appear to be further evidence of the original stencil and designs occurring at different times for some Painted Hands.

Figure 4. Painted Hand at Amarrkanangka. (After Mountford 1956, 178, pl. 48G.)

It is worth noting Chaloupka's discussion of the significance of hand stencils generally, as it relates to ideas of personal identity touched upon in this paper. He states: ‘Almost every person of that generation knew the localities of their own hand stencils and could identify those belonging to others. Some people made stencils of their hand a number of times during their lifetime, in many instances in estates other than their own’ (Chaloupka Reference Chaloupka1993, 232).

Chaloupka argues that the main function of stencils was to record a visit to or association with a particular place, but they were also used to ‘sign’ other paintings. He gives the example of Narlim, a Mengerrdji man who painted a sailing vessel at Warlkarr shelter (Aamarrkananga) and signed his name across the hull of the ship. In addition, Narlim ‘also left a stencil of his hand by which he was remembered by those who could not read’ (Chaloupka Reference Chaloupka1993, 232–3). These examples illustrate the very personal and individual nature of hands in rock art in western Arnhem Land.

Links to ceremony

Taçon (Reference Taçon1989a, 339) associates Painted Hands with death rituals and the Lorrkon ceremony. He states that designs painted on log coffins, human skulls, and on hand or hand and arm stencils contain Rainbow Serpent power associated with Ancestors and help return the dead to clan wells. This corresponds with his example of Neidji painting the hand stencil of a recently deceased woman.

While each of the ceremonies in western Arnhem Land are distinct on the basis of their primary purpose, the link between an individual and their clan country is a common theme. For this reason, people see their multiple ceremonies to be linked into a set for initiation and mortuary purposes (Taylor Reference Taylor1996). For example, Lorrkon addresses the final reburial of a person's bones and the journey of their spirit to important sites in their country. The Mardayin ritual celebrates the spiritual connection of new initiates to their clan lands and to the sacred objects of the clan. As a related theme, Mardayin addresses the issue of the transmission of sacred objects owned by the deceased persons to new senior people. Thus, Lorrkon and Mardayin are considered to be linked in relation to mortuary issues and in respect of the journey of a human soul from the deceased to their clan waterhole where, in turn, the soul can be reborn to new members of the clan. Other features of Mardayin are concerned with the more general release of Ancestral power to ensure the replenishment of the multiple species of the world.

A core theme for all ceremonies is the enduring relationship between particular Ancestral beings, the country created by them and the spiritual connection of individuals to this Ancestral template. However, changes in ceremonial performance are also a feature of the internal dynamics of western Arnhem Land societies. Ceremonies of the same name may vary depending upon the context of where they are held and who is in attendance. Visiting groups may be incorporated, or the presence of new settling groups may lead to more permanent ceremonial change. Respected ceremonial leaders can work with their peers to vary performances to account for different circumstances and to incorporate ceremonial innovations.

The contention of this paper is that such internal processes of change were vastly exacerbated by historical changes wrought by culture contact and colonization processes. Ceremonial change is an important mechanism for adjusting the relationships between groups of people who are moving across the lands of others, or moving to live relatively permanently in new settlements. Changes in the relative importance of different ceremonies, introductions from other regions and the coalition of elements from distinct ceremonies into new amalgams have all been documented over the last 100 years in the region (e.g. Berndt & Berndt Reference Berndt and Berndt1970; Garde Reference Garde, Thomas and Neale2011; Taylor Reference Taylor1996). This is true even as the intimate spiritual links between people and the Ancestors that made the lands is a central concern. Over the generations, people can gain spiritual links with new lands through learning about them, having rights bestowed by landowners in ceremonial contexts, and through the life-cycle of death and conception of children in the new lands.

Transformation in ceremonial practice links with this wider incorporation of change. For example, major regional performances of Mardayin became less important by the late 1960s in western Arnhem Land, although the use of Mardayin body paintings continued in the context of circumcision ceremonies in some areas. Knowledge by artists of Mardayin body paintings and objects also stimulated much experimentation in bark paintings made for sale from the 1970s to the present (Taylor Reference Taylor, McGrath and Jebb2015; Reference Taylor2017).

We would argue that the Painted Hands represent a similar efflorescence, albeit at an earlier date and in a different context. The paintings are innovative productions as the artists respond to changed circumstance and the works create new meaning through the combination of elements that have established reference in other contexts of use.

Chronology

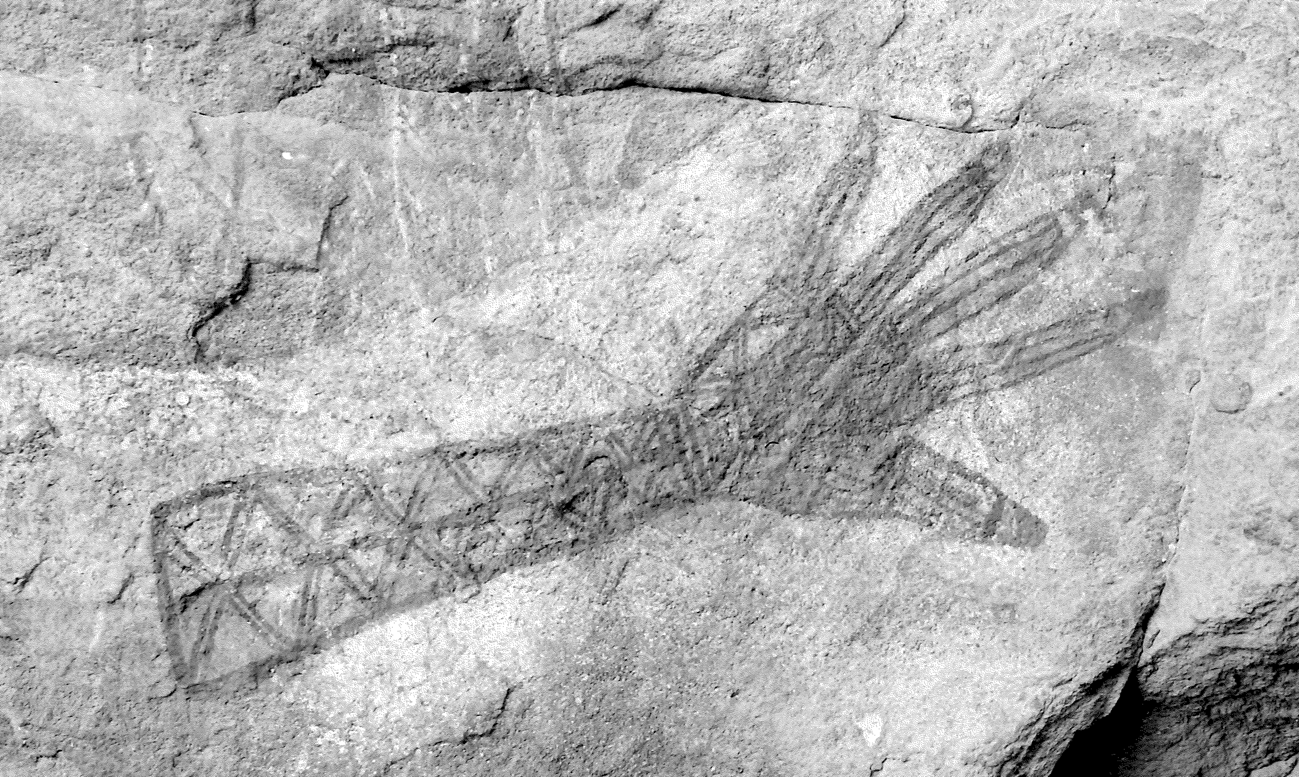

There are a number of factors that come together to suggest Painted Hands were produced in the historical period. First, we have four first-hand accounts of them being created. Famous rock painter Djimongurr (Old Nym) and his son Namandali (Young Nym) produced a painted hand in the Koongarra Saddle area of Kakadu in the late 1950s or early 1960s (Figs. 5 & 6). This evidence comes from Djimongurr's daughter Josie Maralngurra who was with him at the time and witnessed the event (May et al. Reference May, Maralngurra and Johnston2019). At Nanguluwurr, Josie's father also created a Painted Hand from her own hand stencil in early 1964 when she was about 12 or 13 years old (Josie Maralngurra pers. comm., 2019; Fig. 7), a date confirmed by earlier research of painting episodes at the site by Chaloupka (Reference Chaloupka1982, 27–30), Haskovec & Sullivan (Reference Haskovec and Sullivan1986) and Taçon (Reference Taçon1989a: 49).

Figure 5. The Painted Hand (red outlined with cross-pattern design) created by Djimongurr (Old Nym) and his son Namandali (Young Nym) near the Koongarra Saddle. (Photograph: Joakim Goldhahn.)

Figure 6. From left to right: Raburrabu (Mission Jack), Nayombolmi (Barramundi Charlie), Toby Gangale and Djimongurr (Old Nym), c. 1960. (Photograph: Judy Opitz Collection.)

Figure 7. Josie Maralngurra with her Painted Hand at Nanguluwurr. (Photograph: Paul S.C. Taçon, 2019.)

Djimongurr's long-time friend and artistic collaborator Nayombolmi (Fig. 6, also known as Barramundi Charlie) created a Painted Hand in the Balawurru area (Deaf Adder Gorge) with evidence coming from his cousin Nipper Kapirigi, who identified it as his work to Taçon in the 1980s (Fig. 8; see also Haskovec & Sullivan Reference Haskovec and Sullivan1986; Reference Haskovec, Sullivan and Morphy1989). The final (aforementioned) example was created by Bill Neidjie at Amarrkanangka in the 1940s (Taçon Reference Taçon1989b, 25, fig. 34 caption; Fig. 9).

Figure 8. Painted Hand by Nayombolmi, Deaf Adder Gorge, Kakadu. (Brandl Reference Brandl1973, 31, fig. 63.)

Figure 9. A Painted Hand at Amarrkanangka with infill design by Bill Neidjie. (Taçon Reference Taçon1989b, 25, fig. 34.)

Another insight into the age of Painted Hands comes from the incorporation of pigment made using laundry-whitening cubes such as Reckitt's Blue (Fig. 10). Reckitt's Blue was ‘borrowed’ from local settlements, such as Oenpelli, for use as a pigment for painting on rock, bark and a variety of objects (e.g. Chaloupka Reference Chaloupka1979; Reference Chaloupka1982; Reference Chaloupka1993; Haskovec & Sullivan Reference Haskovec and Sullivan1986; Roberts Reference Roberts2004; Taçon Reference Taçon1989a). It was most likely made available via the Kaparlgoo Native Industrial Mission (c. 1899–1903) or Oenpelli settlement (1910–present) and, as such, gives us a terminus post quem for these particular images.

Figure 10. Reckitt's Blue Painted Hand from Awunbarna. (Photograph: Paul S.C. Taçon, 2018.)

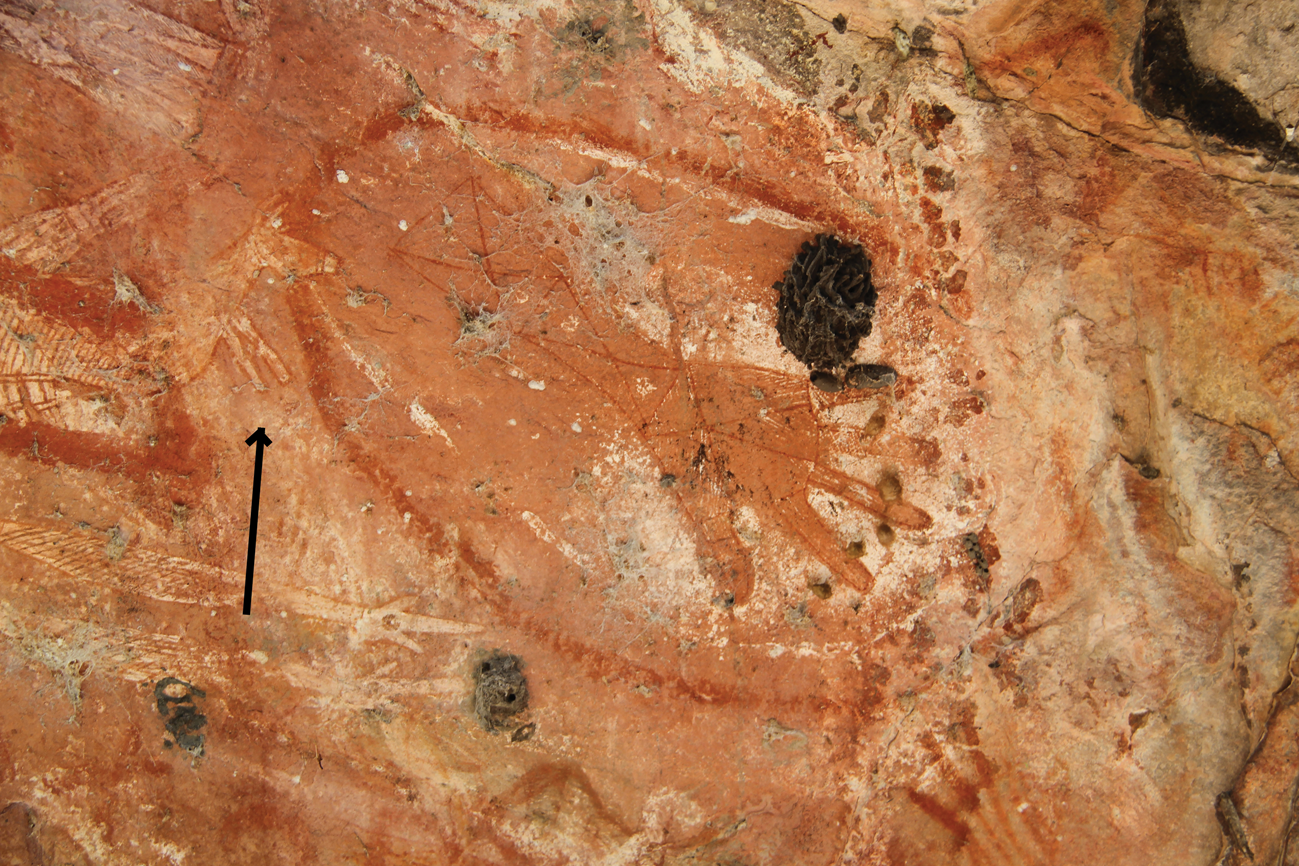

Moreover, Painted Hands are almost always the most recent layer of art at sites. Only three in our sample were overpainted—one by a horse (Fig. 11) and the other by a sailing vessel, and the third by a barramundi (Fig. 7). The later Painted Hand, however, was made by Djimongurr during the same visit to Nanguluwurr in early 1964 (Josie Maralngurra pers. comm., 2019).

Figure 11. Small painting of a horse over the circle surrounding a Painted Hand from Awunbarna. The black arrow points to the front legs of the horse. (Photograph: Paul S.C. Taçon, 2018.)

Finally, a number of bark paintings collected by Paddy Cahill and sent to Baldwin Spencer around 1916 include painted hands, arms and/or feet (Fig. 12). In a letter from Cahill to Spencer accompanying a shipment of barks, he says ‘I am sending you (64) sixty four copies of rock drawings, on bark, I have numbered them all, and written out their names as nearly phonetically as I can’ (Cahill [1914] Reference Cahill and Mulvaney2004; see also Spencer Reference Spencer1914, 432–3). This is important, as it tells us that there were Painted Hands in the rock art prior to 1916. The examples held today in Museum Victoria are wonderfully detailed images incorporating extensive ceremonial designs (Taylor Reference Taylor, McGrath and Jebb2015; Reference Taylor, Brady and Taçon2016; Fig. 12).

Figure 12. Bark painting collected about 1916 by Paddy Cahill in Oenpelli (Gunbalanya) and now held at Museum Victoria. (Photograph: Paul S.C. Taçon.)

With these many clues in mind, we suggest that Painted Hand rock art first emerged around 1900 with the establishment of more permanent settlements at Kaparlgoo and Oenpelli. The last rock-art example was most likely produced by Djimongurr in 1964, though they continue to be painted on art paper and bark by some artists today at Injalak Arts in Gunbalanya (Oenpelli). The date range for the rock art, therefore, is about 65 years, within a single generation. The timing of this rush of Painted Hands in rock art c. 1900 to c. 1964 is important in terms of the events taking place in western Arnhem Land at this time.

Contact and colonial histories

It is important to consider the historical context of this new art style. Aboriginal engagement and cultural entanglements with outsiders in western Arnhem Land has had a long and varied history. Archaeological evidence has been growing to support a long period of engagement between local Aboriginal clan groups and maritime communities from island Southeast Asia from the early to mid seventeenth century (e.g. Theden-Ringl et al. Reference Theden-Ringl, Fenner, Wesley and Lamilami2011; Wesley et al. Reference Wesley, O'Connor and Fenner2016). This long model of interaction is supported by radiocarbon dating of Macassan burials, beeswax dates over images of Macassan praus and the Anuru Bay Macassan trepang-processing site that revealed several phases of use (e.g. Taçon et al. Reference Taçon, May, Fallon, Travers, Wesley and Lamilami2010; Theden Ringl et al. Reference Theden-Ringl, Fenner, Wesley and Lamilami2011; Wesley et al. Reference Wesley, O'Connor and Fenner2016). Macassan trepang (sea slug) processing proliferates in the latter half of the eighteenth century, continuing through to 1907 (Macknight Reference Macknight1976; Reference Macknight2011; Máñez & Ferse Reference Máñez and Ferse2010). Numerous ethno-historic accounts attest to substantial interaction with Aboriginal people working on praus, assisting with trepang fishing and diving, accompanied by the introduction of new materials and substantial changes in social customs and language (cf. Berndt & Berndt Reference Berndt and Berndt1954; Clarke Reference Clarke1994; Evans Reference Evans1992; Ganter et al. Reference Ganter, Martinez and Lee2006; Macknight Reference Macknight1986; Reference Macknight2011; McIntosh Reference McIntosh1996; Reference McIntosh2006; Reference McIntosh, Veth, Sutton and Neale2008; Reference McIntosh, Thomas and Neale2011; Reference McIntosh, Clark and May2013; Mitchell Reference Mitchell1996; Reference Mitchell, Torrence and Clarke2000; Morphy Reference Morphy1991; Russell Reference Russell2004; Warner Reference Warner1932).

Following these early encounters, British attempts to colonize the north coast of Australia began in the early nineteenth century. European settlements such as Fort Wellington (1827-–29) and Port Essington (1838–49) on the Cobourg Peninsula to the north and the later Escape Cliffs (1864–67) to the west of Arnhem Land all had lasting impacts on local Aboriginal populations and customary systems (e.g. Allen Reference Allen1972; Evans Reference Evans2000). The establishment of Port Darwin in 1869 created a nexus for incoming pastoral selectors, mining prospectors and a variety of entrepreneurs that began to exert pressure on and create conflict for Aboriginal groups in the wider region (Powell Reference Powell1988; Robinson Reference Robinson2005; Wells Reference Wells2003). This signalled the beginning of the sustained momentum of European settlement and economic development.

The European economic and social history of the Arnhem Land region is largely defined by hardship and isolation, with mining prospection, pastoral stations, buffalo-shooting enterprises, pearling, dingo scalping, crocodile hunting and timber milling predominant (e.g. Levitus Reference Levitus1982; Reference Levitus, Press, Lea, Webb and Graham1995). Aboriginal labour was incorporated into these European enterprises (Robinson Reference Robinson2005). At the same time, diseases such as influenza, malaria and whooping cough (to name a few) were devastating local communities (e.g. Harris Reference Harris1998, 191; Spillett Reference Spillett1972, 145). In short, Aboriginal people experienced regular and sustained encounters and engagement with all these European enterprises throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, thereby creating multiple modes of influence, stress and conflict.

These events naturally had a severe impact on cultural practices. With the loss of life and the movement of people across the region, people were forced to re-evaluate their priorities, including commitments to ceremonial life. For example, particular ceremonies seemed to have been abandoned and new ones introduced (Berndt & Berndt Reference Berndt and Berndt1970, 124; Garde Reference Garde, Thomas and Neale2011; Thomson Reference Thomson1949).

Distribution

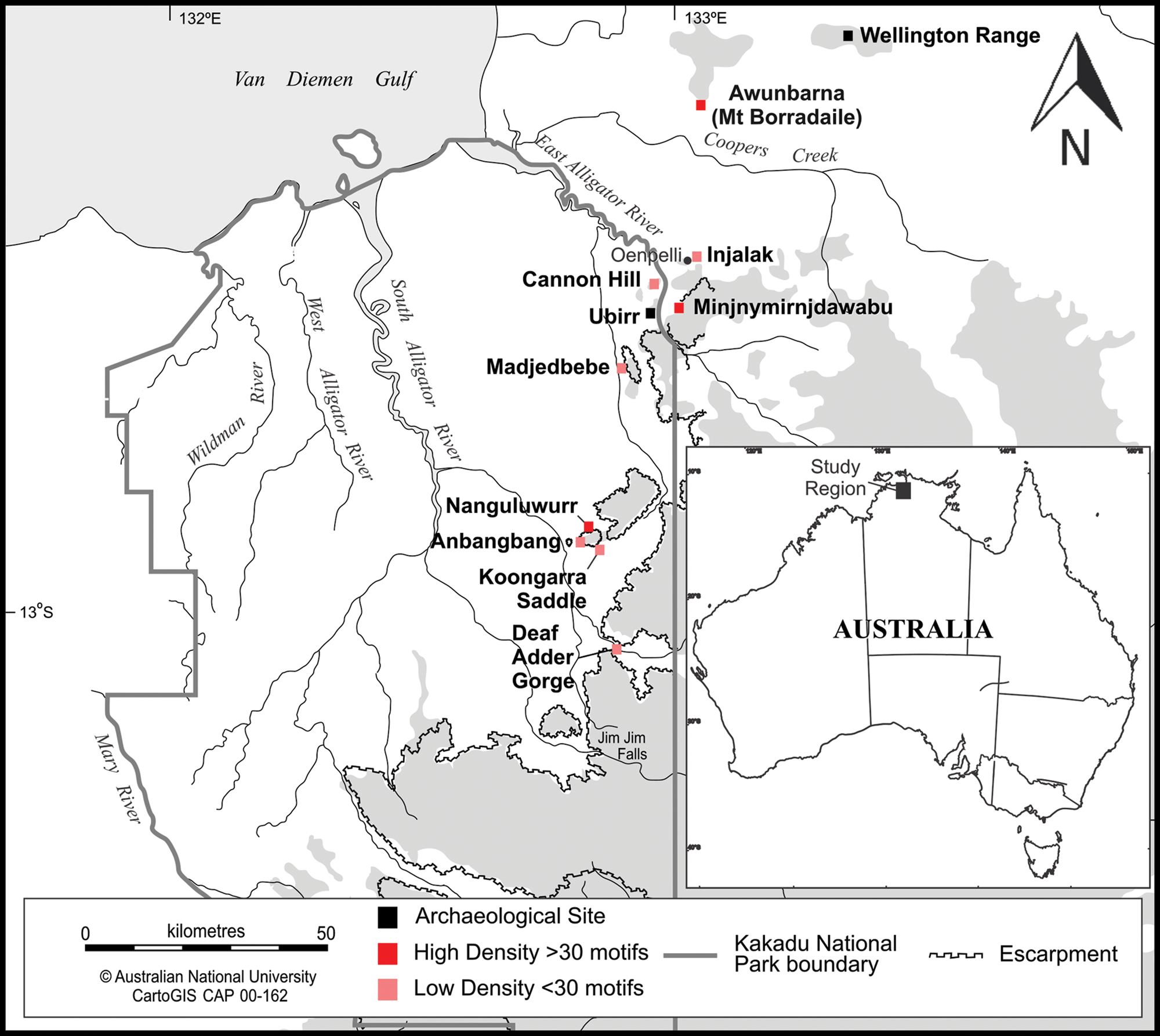

There is no doubt that Awunbarna is the epicentre for Painted Hand rock art, as also noted by Chaloupka (Reference Chaloupka1993, 214) (Fig. 13). Our team has to date documented over 200 such paintings in the Awunbarna area, with many others yet to be properly recorded. Interestingly, despite over a decade of rock-art survey in the Wellington Range (to the north of Awunbarna), no Painted Hands have been recorded in this northern region. This is despite extensive historical-period rock art known to exist in the area (e.g. May et al. Reference May, Taçon, Guse and Travers2010; Reference May, Taçon, Paterson and Travers2013; Taçon et al. Reference Taçon, May, Fallon, Travers, Wesley and Lamilami2010). To the south of Awunbarna, Minjnymirnjdawabu is home to over 40 examples recorded to date, and Nanguluwurr (Nangalore/Nangalawur) in Kakadu has 35 surviving examples (see also Jelínek Reference Jelínek1977; Reference Jelínek1989; Fig. 14). Outside these hot spots, other examples have been noted on Injalak Hill near Gunbalanya as well as Burrungkuy, Koongarra, Madjedbebe (May et al. Reference May, Taçon, Wright, Marshall, Goldhahn, Domingo Sanz, David, Taçon, Delannoy and Geneste2017a), Balawurru (Deaf Adder Gorge) (Brandl Reference Brandl1973; Haskovec & Sullivan Reference Haskovec and Sullivan1986; Jelínek Reference Jelínek1989) and Amarrkanangka (Jelínek Reference Jelínek1989; Taçon Reference Taçon1989b) in Kakadu.

Figure 13. Location of known key Painted Hand sites. (Map: Daryl Wesley.)

Figure 14. A selection of the Painted Hands from Nanguluwurr. (Photograph: Sally K. May, 2018.)

Chaloupka (Reference Chaloupka1993, 214) argues that, because Awunbarna is the epicentre, it must have been the Victoria Settlement (Port Essington) that inspired the Painted Hand style. While we agree that Awunbarna is the key to the story, we believe the spread of the Painted Hands tells a slightly different tale. This north–south axis of key sites suggest that no single historic place influenced the emergence of this style.

Most of the Painted Hands appear at a few key sites within these larger areas. As argued by May et al. (Reference May, Wesley, Goldhahn, Litster and Manera2017b) and Gunn et al. (Reference Gunn, David, Whear, David, Taçon, Delannoy and Geneste2017a), historical rock art in Arnhem Land tends to cluster at key sites in the landscape. This is also true for the Painted Hands, with Madjedbebe, Nanguluwur, Minjnymirnjdawabu and Awunbarna having a significantly higher number of individual Painted Hands than anywhere else. They are all located along known historic walking routes that extend much further north towards the Cobourg Peninsula and the early British settlements in that area (e.g. Chaloupka Reference Chaloupka and Stokes1981; Gunn et al. Reference Gunn, Douglas and Whear2017b; Layton Reference Layton1981). These historic routes must have been essential for communicating information relating to this turbulent period in history (May et al. Reference May, Taçon, Wright, Marshall, Goldhahn, Domingo Sanz, David, Taçon, Delannoy and Geneste2017a). The clusters of Painted Hands also align with other clusters of introduced imagery in rock art, such as firearms at Madjedbebe (May et al. Reference May, Wesley, Goldhahn, Litster and Manera2017b) and sailing vessels at Awunbarna (Roberts & Parker Reference Roberts and Parker2003). The Painted Hands are, therefore, part of an important communication pathway and central to the contact narrative of the time.

Discussion

The original and widely accepted interpretation of the Painted Hands is Chaloupka's (Reference Chaloupka1993, 214) argument, discussed above, that they imitated the gloves worn by Europeans at early British settlements. We would argue that this interpretation is far from the truth and is, most likely, a story made up to deflect attention away from these highly significant motifs (cf. Brady et al. Reference Brady, May, Goldhahn and Taçonin press). Indeed, we are unable to share certain aspects of the interpretation due to restrictions on cultural knowledge. However, it is clear that many of the Painted Hands include designs relating directly to ceremonial activities. These designs are embedded with cultural meaning that can only be fully understood or interpreted by someone who has passed through a particular ceremony (see Taylor Reference Taylor1996). In this way, rock art and other forms of art from western Arnhem Land have many layers of meaning depending on who is viewing them. Figures 15 and 16 are good examples of these ceremonial designs. The designs on both the Painted Hand (Fig. 15) and the bark painting of the yam (Fig. 16) relate to ceremonial designs; initiated individuals would read into these designs far greater detail of place, person, clan, moiety and more (see Taylor Reference Taylor1996).

Figure 15. A Painted Hand from Minjnymirnjdawabu. (Photograph: Paul S.C. Taçon.)

Figure 16. Bark painting by an unknown artist from the Oenpelli (Gunbalanya) area collected by Paddy Cahill c. 1916 and now held at Museum Victoria. (Photograph: Paul S.C. Taçon.)

The Mardayin ceremony was one of the most important in western Arnhem Land in the early twentieth century (Berndt & Berndt Reference Berndt and Berndt1970). As mentioned previously, performances were strongly interlinked with other regional ceremonies in terms of initiation and mortuary cycles. Today, Mardayin is not performed as a separate ceremony, but some of its components have been melded with new, and more popular, ceremonies introduced from southern Arnhem Land. Artists continue to use imagery relating to this ceremony in their art today (Taylor Reference Taylor2008). As Taylor (Reference Taylor, Brady and Taçon2016, 314) describes, Mardayin celebrates the spiritual links between people and their originating Ancestral beings through the painting of designs called rarrk on their bodies and through being shown the sacred objects for the clan that are painted with similar designs. The designs represent important Ancestral sites in their clan lands and the act of being painted effects the physical union of the initiate with the Ancestral powers of their country. The dotted diagonal cross-shaped motifs featured on some Painted Hands echo body painting of the Mardayin ceremony, as also seen on other material culture such as men's baskets (Taylor Reference Taylor, Brady and Taçon2016, 314–15):

The geometric frameworks of these designs include variations of diagonally crossed squares, rectangles, or triangular forms, with the inclusion of circular elements. The designs vary for different clans and the reference is a matter of ceremonial revelation. (Taylor Reference Taylor2008, 874).

We are using the Mardayin Painted Hands as an example—other Painted Hands include cultural and ceremonial design elements from other ceremonies, such as Wubarr and Lorrkon, which are linked with Mardayin. We are still exploring these connections with Senior Aboriginal Traditional Owners. Our point here is to emphasize that many of these Painted Hands were deliberately used during the recent past as a method for communicating inside ceremonial knowledge across a broad landscape. The use of the human hand to achieve this was particularly innovative: nothing like this existed before in the rock art from western Arnhem Land. The new creativity rests on combining, for the first time, a depicted hand figure, which is seen as the bodily trace of individual people who have visited a site, with geometric elaborations that identify spiritual connections between individuals and specific Ancestral country.

An important detail here is that many of the Painted Hands are encircled by single or double lines, particularly around Awunbarna. Taylor (Reference Taylor1996) demonstrates the significance of encircling of a figure in western Arnhem Land art, in this case a bark painting produced in 1975 by artist Milaybuma:

Many paintings of fish are suggested to be ‘just a fish’, a fish you can find in any waterhole. However, some Kunwinjku can paint the barramundi djang associated with Born clan lands and such works are associated with the fertilizing power of this original being. One way of indicating that the fish is djang is to include rarrk infill. Another way is to depict the fish inside a circular line as represented in the example by Milaybuma … This line represents the fish inside the rock at the site. Kunwinjku commonly use this means to show the djang species inside the waterhole or rock at a site. The painting of this barramundi associates the subject with ideas concerning the power of the site and the potential to use this power to ensure the increase of the species as the djang for barramundi is associated with increase rituals to ensure the renewal and plentiful supply of barramundi. (Taylor Reference Taylor1996, 157)

The ritual significance of encircling a figure is clearly articulated in this example and emphasizes that it is far more than a simple framing device inspired by Europeans (cf. Chaloupka Reference Chaloupka1993, 214). It is interesting to consider, then, how this might apply to Painted Hands and why this became a key component in this design. While the barramundi painting discussed by Taylor (Reference Taylor1996, 157) is linked to increase rituals, Kuninjku use circles around a figure to indicate that the subject is djang (Ancestral creator beings) inside a particular creation site. In such cases, the circle can be read as the outline of a waterhole wherein the spiritual essence of the djang creator being still resides (see Taylor Reference Taylor2017, 36). Circles incorporated in Mardayin designs are usually interpreted this way by Kuninjku: they are important waterholes created by Ancestral beings where the unborn spirits of the clan reside. The souls of deceased members of the clan return here when they die and may eventually be reborn. These sites are associated with the fertilizing essence of Ancestral beings that may be released in ceremony to ensure the fertility of natural species. However, this same power can be drawn into ceremonial processes that ensure the continued rejuvenation of the clan. The Rainbow Serpent, Ngalyod, protects such places. Occasionally, in Kuninjku bark paintings and drawings, the circle can be replaced with the circular form of the Rainbow Serpent, highlighting its ubiquitous relationship with Ancestral transformation, specific clan country, site creation and sacred waters.

Frames placed around many of the Painted Hands may refer to this sacred country. The image as a whole may indicate the spiritual essence of individuals inside their sacred waters. This reading would accord with the use of frames/circles, at least by Kuninjku. As such, it could be indicating a range of ritual roles for the art and the creators of the art. Were the artists trying to indicate the ritual significance of the individual whose hand was represented? Was the production of the image intended to affect the return of their spirit to their country? Are these hands related to the rejuvenation of their clan spirit? Following his own words, Neidji's hand painting at Amarrkanangka appears to have this mortuary element. Thus, an artist who knows the identity of the creator of the original hand stencil modifies the image upon their death. The addition of the circle and geometric infill may cleanse the shelter of the deceased's lingering spirit, encouraging it to return to clan waters.

Painted Hands may be related to the dramatic loss of life in this region around 1900, a point in time when disease and murder wiped out a large proportion of the population. Indeed, Ian Keen (Reference Keen1980, 171) estimates the population was only 3–4 per cent of what it had been before ‘contact’. At this time there were active travel routes, that incorporated rock-shelters as stopping points, to newly established settlements, as well as enhanced population movements by people from the north, east, and south into depopulated lands.

Overall, it would seem that the Painted Hands are a very particular and very recent creation consistent with the themes expressed in ceremonies such as Mardayin and likely triggered by enhanced individual mobility as well as broad-based population movements post contact. It is clear that contact with balanda (non-Indigenous people) was a key motivation in the emergence of the Painted Hands. The invasion of Aboriginal lands—from missionaries, to miners, buffalo shooters and more—presented new challenges to and caused immense stress for local Aboriginal people. So are the Painted Hands a direct result of this stress? We would argue that they are, but in a more indirect way.

As discussed earlier, rock art has the remarkable ability not only to reflect periods of stress within and between different societies but also to play an active role in assisting these groups in navigating these experiences (e.g. Frieman & May Reference Frieman and May2019). It should follow that sudden, obvious shifts in style evidenced in the archaeological record may be indicating such episodes. In the case of the Painted Hands, we would argue that they also represent a way for the moving Aboriginal families and, ultimately, populations to form attachments to new places. Just as hand stencils sometimes marked a visit to a different clan estate (e.g. Chaloupka Reference Chaloupka1993, 232), Painted Hands may reflect an attempt by visitors to establish amicable, exchange-based relationships with the Aboriginal landowners of the territory in which they found themselves post contact. In this way, the Painted Hands may have also helped to create amicable relations with neighbouring clan groups during times of population movement across the landscape.

The movement of people and ceremonies into and out of western Arnhem Land throughout the historical period is well documented (e.g. Berndt & Berndt Reference Berndt and Berndt1970, 124; Garde Reference Garde, Thomas and Neale2011, 20; Keen Reference Keen1994). The exchange of ceremonies, including associated iconography, likely played a role in these movements, helping to establish these new relationships. As Garde (Reference Garde, Thomas and Neale2011, 420) states:

Across much of Arnhem Land today, large regional ceremonial rites are regarded as important contributors to social cohesion. In my experience, such ceremonies represent important occasions for people from many disparate groups to work together for the purpose of achieving a sense of the ‘corporate good’.

This idea of ceremony contributing to social cohesion is central to our argument for the emergence of the Painted Hands. Arising as an innovative rock-art style around 1900, the Painted Hands played a key role in the sharing of ceremonial knowledge, connecting with Ancestral beings, and the establishment of new relationships during a period of intense change.

Conclusion

The emergence of the Painted Hand rock-art style is a surprisingly recent phenomenon and reflects the experiences of Aboriginal people across western Arnhem Land from the early to mid 1900s. The humble human hand with, often, elaborate design elements represented a dialogue that would have been largely invisible to, and uninterpretable by, non-Aboriginal people. The Painted Hands represent a safe space in which to grapple with the realities of a rapidly shifting world and way of life. They were not stagnant, redundant images, but rather they played an active role in helping communities to navigate their lived experiences by constantly creating a connection between living communities and place as well as between the living, the Ancestral world and the dead. Anyone visiting these rock-shelters engaged with this imagery and re-activated their varied messages. While the original painting event or events formed a crucial aspect of their story, the cultural knowledge and personal links associated with the Painted Hands ensured they continued to play an active role in society. As one of the last major rock-art styles introduced into the rock art of western Arnhem Land, the Painted Hands represent the complexity of Australian rock art and its role in helping people to navigate the most challenging of times.

Acknowledgements

We thank the following people and organizations for sharing their time and knowledge with us: J. Galareya Namarnyilk (dec.), T. Yulidjirri (dec.), Bardayal Nadjamerrek (dec.), Donna Nadjamerrek, J. Nayinggul (dec.), Alfred Nayinggul, Connie Nayinggul and family, Jeffrey Lee, Josie Maralngurra, Christine Nabbobob, Kadeem May, Gabrielle O'Loughlin, Parks Australia, Injalak Arts, Bridget Thomson, Ray Curry, Lee Davidson, Davidson's Safari Camp and the Northern Land Council. We are grateful to Iain Johnston, John Hayward, Liam Brady, Samuel Dix, Andrea Jalandoni, Fiona McKeague and Roxanne Tsang for collaborating on fieldwork and for inspiring discussions. Thanks to John Hayward for providing the count of painted hands at Nanguluwurr and Murray Garde for advice on Aboriginal place names. SKM and PT's research is funded by the ARC grant FL160100123 ‘Australian rock art history, conservation and Indigenous well-being’, part of Paul Taçon's ARC Laureate Project. The new recordings from Nanguluwurr, Koongarra and Burrungkuy were made as part of the ‘Pathways: people, landscape and rock art’ project, a collaboration with Senior Traditional Owner Jeffrey Lee, Josie Maralngurra, Christine Nabobbob and Parks Australia. Many thanks to Judy Opitz for allowing us to use her photo. CJF's participation was supported by ARC DECRA Project DE170100464. DW was supported by ARC DECRA Project DE170101447.