The complex constructions of the ‘figure’ of Sappho have enjoyed remarkable scholarly attention in recent years: this is due in part to the extraordinary capacity that Sappho's texts and her later recreations had to resonate within a lively and diverse reception, and, on the other hand, to an important increase of our knowledge of her texts, thanks to the publication of new papyrus fragments. And yet Sappho's ‘constellation’Footnote 1 remains as problematic and elusive as it is productive. To a degree even more marked than for most other archaic authors, we are faced with a strong divergence between the tradition that underlies the formation of a corpus of poems attributed to ‘Sappho’ – which finds a fundamental systematisation in the Alexandrian period in what we can define as the ‘standard’ edition – and the tradition of ‘Sappho’ as a cultural icon, which goes back to a very early period as witnessed by a surprisingly rich group of representations on vase paintings, starting from the late-sixth century.Footnote 2 It would be a mistake to consider the latter simply a deformed reception of the ‘scholarly’ textual tradition, which in its turn is the result of a still largely obscure development. It is this second tradition, in fact, that has arguably had the stronger impact in Sappho's reception and for rather more than a millennium contributed to the construction of the various ‘Sapphos’ who have populated Western culture.

When, in 1816, Friedrich G. Welcker published his little book on Sappho Rescued from a Dominant Prejudice,Footnote 3 he had among his avowed purposes exactly that of clarifying the distinction between the two traditions, by applying the groundbreaking scholarly method of Quellenkritik of the new ‘philology’. In this context Welcker attributed a fundamental role in the development of the Sapphic tradition to the deformations that her character suffered within Attic comedy. Since then comedy continues to occupy a conspicuous role within treatments of the figure of Sappho. And yet the evidence actually provided by extant comic texts is very exiguous indeed. With a single possible, rather evanescent, exception (Amipsias, with a play that could be dated in the late-fifth century), we are dealing with fourth-century texts, mainly attributable to Middle and New Comedy.Footnote 4 Only for very few of these can we gather anything more than an extremely vague idea. This is the case with Antiphanes, where Sappho appears as the creator of riddles, and with Diphilus, where she is anachronistically wooed by Archilochus and Hipponax. It is possible that Sappho may have appeared in a fifth-century comedy of Cratinus (fr. 370 K.–A.) where an allusion is documented to Phaon, the mythical and elusive ferryman loved by Sappho in later traditions but never attested in actual Sapphic texts.Footnote 5 Even in the case of Cratinus, however, where Phaon appears as loved by Aphrodite, as well as in the later Phaons of the comic poets Plato and Antiphanes, there is no evidence that Sappho was even mentioned, let alone that she appeared as a character.Footnote 6

There is, however, an important piece of evidence for Sappho's presence in (or, at the very least, influence on) in a text belonging to the period of Old Comedy, to be dated possibly to the 420s, which seems to have escaped critical attention so far. If my argument is correct, this would allow us to reconstruct a key role for Sappho in a comedy with an eschatological focus, and to show how at this stage ‘Sappho’ had become part of a representation of the underworld for which we only have few and highly debated clues in her ‘textual’ tradition.

1. The leap, and beyond

We know rather little of Pherecrates’ Miners. All we can say about its plot derives from its title and two textual fragments, even if one of them, with its thirty-three iambic trimeters, is in fact the longest verbatim quotation we have from its author.Footnote 7 It is a detailed description of the Underworld as the Land of Cockaigne, where rivers flow rich in food, where roasted birds fly directly in people's mouths, where beautiful fruit grows by itself, and fragrant wines are served by girls blooming in their youth, wearing thin veils. This passage belongs within a chain of variations on a topos of Old Comedy documented by Athenaeus, within his survey, accompanied by ample quotations, in chronological order, of instances of the automatos bios (6.267e–270a).Footnote 8 The sequence includes Cratinus’ Ploutoi, Crates’ Theria, Telecleides’ Amphictyones, Pherecrates’ Miners and Persians, and Aristophanes’ Tagenistai (Roasters), with mentions of Nicophon's Sirens and of Metagenes’ Thouriopersai. The evidence points to the conclusion that these comedies were all composed during the Peloponnesian War. In the case of the long quotation from the Miners a striking effect would have arguably been produced by the stark contrast between the idealised blessed life of the Underworld and the horrible, hellish working conditions of Laurion's silver mines, the most likely location for an Attic chorus of miners. A most peculiar element is provided by the interruption of this long description by a second character at lines 20–1:

This second character (‘character B’) expresses in a rather colourful way his or her impatience. From his/her words we understand that the dialogue takes place in the world of the living (ἐνταυ̑θα) and that the character who delivers the long description (‘character A’) is a woman (as implied by the feminine participle (διατρίβουσ(α)) who has come back from the Underworld, and whose leisurely description of its wonderful joys is contrasted by ‘character B’ with the possibility of ‘diving into Tartarus’ immediately.Footnote 9 The identity of ‘character A’, who has experienced the pleasures of the Underworld, and who could dive into Tartarus, has remained so far an unsolved riddle.Footnote 10 There are, however, some important clues that can help us to get closer to the solution. In the first place, the image used to describe ‘character A’'s potential access to Tartarus deserves particular attention. There is, in fact, a famous female character well known for her fatal leap into the sea, and to whom abundant, if controversial evidence, attributes a privileged position in the kingdom of the dead. One of my aims in this paper is to argue for the identification of ‘character A’ with Sappho (or, at least, for a very strong link between them).

The image of the dive into Tartarus, as noted by all commentators, evokes Anacreon's representation of his crazy dive from the Rock of Leucas (376 PMG = 94 Gentili, 23 Leo):Footnote 11

The story of Sappho's leap from the Rock of Leucas is developed in full, among the sources available to us, in Sappho's Epistle to Phaon attributed to Ovid,Footnote 12 but is attested for the first time in Menander's Leucadia (fr. 1 Austin, Blanchard, 258 K.–T.),Footnote 13 a passage quoted by Strabo (10.2.9, 452c) as evidence that the poetess was the first one to threw herself from the promontory occupied by the famous temple of Apollo:Footnote 14

From what we know of the remnants of Menander's play, Sappho's story was not properly part of the plot, which, as usual in his comedies, dealt with contemporary events. It is clear that the story belonged to the traditional repertoire of tales on the poetess. Anacreon's image plays on the topical repetition (δηὖτε, ‘look, once again’) of a situation that is naturally extreme, and, one can imagine, hardly likely to be repeated.Footnote 16 The usual and very reasonable assumption is that Anacreon's image is inspired by the use of a similar image (a metaphor or a simile) already in Sappho that would be at the origin of the biographical tradition,Footnote 17 one of the several tesserae of the complex and creative intertextual link between Anacreon and Sappho. The use of the verb κολυμβάω in Pherecrates is also of some interest: it is rarely found in poetry and the passage in Anacreon is likely to be its earliest attestation (as a simple or compound verb) before the later-fifth century.Footnote 18 It occurs also in the title of a mysterious work of Alcman, Κολυμβῶσαι, The Women Who Dive, which (according to a very dubious source) would have been found buried by the head of the otherwise unknown Tyronichos (Tynnichos?) of Chalcis.Footnote 19 This too may point to an act of diving connected with radical changes of state, metaphorical or not.Footnote 20 There are, however, serious doubts regarding the actual existence of such a work.Footnote 21 The fact that in this title, too, we are dealing with female divers suggests, at any rate, that this might also be relevant to the constellation of passages we are examining here.Footnote 22 And, of course, the piece of information about the funerary use of a roll with this work – be it real or fictional – does evoke interesting eschatological implications.

If this reconstruction of the play is correct, Pherecrates may be our earliest evidence for an evolution in the reception of Sappho which was eventually to give her story a special prominence in relation to ideas about the Underworld and more specifically about the fate of the soul after death, which will be the focus of the next section of this study. The leap into sea from the White Rock/ the Rock of Leucas indeed can be easily read as a metaphor of the passage to the afterlife.Footnote 23 This is image has been detected, more or less convincingly, also in funerary iconography starting from the late-sixth century: in the so called Tomb of Hunting and Fishing (Tarquinia, around 520 BCE), and, more convincingly, in the Tomb of the Diver (Paestum, around 500–475 BCE).Footnote 24 In the case of the latter, the presence of a sympotic setting in other sections of the tomb has suggested the possibility that the dive might have been connected with mystery rites linked with the representation of the afterlife as involving the banquet of the blessed ones.Footnote 25 Some scholars, on independent grounds, have argued that the description of the Underworld Land of Cockaigne in Pherecrates might also be read as a parody of such expectations, though this too remains uncertain.Footnote 26

In any case, an eschatological reading of Sappho's leap is definitely attested some centuries later in the complex iconographic apparatus of one of the most impressive and enigmatic monuments of early Julio-Claudian Rome, the so-called Basilica near Porta Maggiore. This fascinating underground building was discovered by chance a little more than a century ago during repair works on the Rome-Cassino railway in 1917. It is dated to the late-first century BCE or the early-first century CE: it was built several metres below the level of the road in a zone of the city that hosted the funerary ground of the influential family of the Statilii Tauri and close to the horti Tauriani. The building, which has the structure of later basilicas, and in many respects anticipates features of the much later Christian ‘churches’, is richly decorated in various ways, most remarkably with stuccoes (originally partly painted), as part of an ambitious iconographic project. Following its discovery and publication it sparked a lively debate, especially among archaeologists and scholars of ancient religions. And while it continues to attract attention in these fields, it hardly features (beyond relatively few bare mentions in lists of images and footnotes) in the flourishing recent (and less recent) studies on Sappho's reception.Footnote 27

The interpretation of the building's general iconographic project is difficult. Some of the images seem to belong to an ‘Orphic-Dionysiac’ background;Footnote 28 others are less clearly defined but do lend themselves to a reading as representations of (symbolic) death and new birth; others still feature scenes of life in the world of the living and – it has been argued – in the Underworld. The series includes mythical scenes such as the abduction of the Leucippids and of Ganymede, Pentheus torn apart by the Bacchae and the punishment of Marsyas. The most influential reading of the complex, which with some divergences of detail is still generally accepted by most scholars, is that developed by François Cumont and later by Jérôme Carcopino, who proposed a religious interpretation of the building as related to a mystery sect, even though their specific identification of this sect with the ‘Neopythagoreans’ has been variously qualified or rejected.

The topographic location of the building, near the cemetery of the gens Statilia and the horti Tauriani, is one of the grounds that have led to posit of a link with the family of the Statilii Tauri. Titus Statilius Taurius, consul in 26 and in 7 BCE, had been at the command of the land forces of Augustus’ army at the battle of Actium. Α few decades later, in 53 CE, under Claudius, his grandson, consul in 44 CE, was accused of being embroiled in magicae superstitiones (Tac. Ann. 12.59.2) and committed suicide before the process took place. The properties of the family seem to have been requisitioned by the state following his suicide (but the family did not suddenly disappear: his daughter, or niece, Statilia Messalina, was to become Nero's third wife).Footnote 29

A key argument for the Neopythagorean hypothesis was provided by the impressive scene depicted in the Basilica's apse (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. The apse of the underground Basilica near Porta Maggiore after the most recent restoration. © Soprintendenza Speciale Archeologia Belle Arti e Paesaggio di Roma

The scene represents on the right side a female character, holding with her right hand her veil filled by the wind and in her left hand a seven-stringed lyre, and stepping beyond the edge of a rocky cliff, accompanied, or pushed, by a little Eros. Before her is the sea, from which a muscular figure, apparently a Triton,Footnote 30 emerges from the waist upward spreading a textile to welcome the arrival of the woman, the tip of whose right foot seems already to touch his left hand. To his right a further marine figure might be another Triton, holding an oar and a trumpet.Footnote 31 Above him, on the summit of an isolated, higher, rock, Apollo faces towards the woman, holding a bow in his left hand, and stretching his right arm towards her. After a few uncertain attempts at making sense of it, the scene was brilliantly interpreted by Densmore Curtis in Reference Densmore Curtis1920 as a representation of Sappho's leap from the Leucadian Rock, in the presence of Apollo, the patron deity not only of the local temple but also of the nearby sanctuary of Actium (which is arguably important with regard to the possible role played by Titus Statilius Statius).Footnote 32 After a few marginal hesitations, this interpretation has established itself, and is now generally accepted.

Carcopino found in this representation of Sappho's fatal leap an important clue for a ‘Neopythagorean’ reading of the Basilica, connecting the scene to Pliny, HN 22.20, a passage illustrating the magical properties of the eryngx or eryngium, a herb considered responsible for Sappho's falling in love with Phaon, and apparently much appreciated by Pythagoreans (test. 211b Voigt (only up to the word Sappho): portentosum est quod de ea [sc. erynge] traditur, radicem eius alterutrius sexus similitudinem referre, raro inuenta, set si uiris contigerit mas, amabiles fieri; ob hoc et Phaonem Lesbium dilectum a Sappho, multa circa hoc non Magorum solum uanitate, sed etiam Pythagoricorum).Footnote 33 The connection in itself is far from cogent, as Pliny only implies that the Pythagoreans had something to say on the herb, but does not state that they mentioned it in connection to Sappho. Carcopino also pointed to the important role played by Nigidius Figulus in the formulation of ‘Neopythagoreanism’ in late Republican Rome, suggesting that his theories may have influenced the iconographic programme of the building. Some progress on this front was made by more recent scholars (especially Sauron (Reference Sauron1994)), but a precise identification of the religious background of this extraordinary monument cannot be made with any certainty. It will probably be safer to define it as eclectic, or syncretistic.Footnote 34 In any case, whatever label we wish to impose on these images, one can hardly doubt the central role of an allegorical/eschatological interpretation of Sappho's leap as representing the passage of the soul to a better life.

It is less certain how we should read the lower left portion of the decoration of the apse, representing a male figure wearing a short mantle, facing right, sitting on a rock by the sea in a pose of mourning (his cheek leaning on the palm of his hand). His interpretation as a repentant Phaon has no support in extant texts. M. Detienne (Reference Detienne1958) read the figure as Odysseus on the island of Calypso, proposing a link to a Neoplatonic allegorical reading of the episode. More recently an identification with Philoctetes has been proposed (Cruciani (Reference Cruciani2000)). None of these seems compelling, but Detienne's remains in my opinion the most attractive.

Within the very rich iconographic project of the Basilica there is another image that might be relevant to our argument. On the ceiling of the right (south) nave several scenes have been identified as representations of the blessed afterlife, along with mythological ones that can be read with varying degrees of certainty as exemplary for the various destinies of the soul. Among these scenes there is one depicting three wreathed female characters (Figs. 2a and 2b). The one to the left, entirely wrapped in her garments, is sitting facing the other two characters and is playing a musical instrument, identified by Carcopino as a lyre, and more precisely, by Bendinelli, as a triangular harp: he calls it a τρίγωνον, but given its shape it could be rather a πηκτίς, especially if one thinks, with West and others, that the term τρίγωνον referred more particularly to the right-angled ‘spindle harp’.Footnote 35 The second character, to the right of a small altar placed before a pillar,Footnote 36 stands facing a female figure (with bare shoulders, i.e. younger?) seated to her left, to whom she seems to be giving an object which has been very dubiously interpreted as a plectron (Carcopino (Reference Carcopino1926) 143). To judge from the most recent available image (Fig. 2a), it looks more as if she is a holding an ampoule with a long neck and a single handle (a small lekythos?), while the woman in front of her is extending a small cup (?) in her right hand (in any case, the kind of harp represented in the same scene was not played with a plectron). Strong and Jolliffe (who label this a ‘Group of Muses (?) or of initiates’) compare the scene to the ‘sacred conversations’ of Renaissance painting ((Reference Strong and Jolliffe1924) 94 n. 81), Carcopino gives it the vaguely suggestive label of ‘mystic concert’, while Bendinelli, with some reservations, interprets it as a music lesson. If we should indeed imagine that the scene takes place in the Underworld (as all scholars seem to do), it would be very attractive to link the wreathed female figure playing the string instrument with Sappho, to whose underworld performances we shall have occasion to return.Footnote 37

Figure 2a. Detail of a panel from the vault of the right nave of the underground Basilica near Porta Maggiore. © Soprintendenza Speciale Archeologia Belle Arti e Paesaggio di Roma

Figure 2b. A drawing of the detail in Fig. 2a. Source: Bendinelli (Reference Bendinelli1926), Table xxvi

2. Sappho rediuiua?

It is of course not necessary to suppose that the character who has just returned from the Underworld in the Miners was represented as an ‘initiate’, since Pherecrates’ parody focuses on other aspects. There are, however, several good reasons to think that this character is likely to have been Sappho herself. We have examined above the evidence for her presence on the Athenian stage in the fourth century, and the clues pointing to possible earlier comic Sapphic links already in the fifth century. There are other reasons for proposing this identification. An important recurring theme in Old Comedy is that of bringing back to life on stage ancient characters either through a visit to the Underworld (katabasis) or by having them return to the upper world (anabasis). Examples of this include Cratinus’ Archilochoi and Cheirones (and perhaps also Laws, according to Bergk's reconstruction), Telecleides’ Hesiodoi, Aristophanes’ Gerytades and Frogs, and Pherecrates’ Krapatalaoi (besides, of course, his Miners).Footnote 38 In some of these plays, known through a number of fragments and quotations (twenty or more) far greater than is the case of the Miners, we can reconstruct the presence and the identity of the revenant only on the basis of a single piece of evidence. In the Cheirones we can recognise Solon as a persona loquens only because of a quotation of a line in Diogenes Laertius (fr. 246 K.–A.). In Pherecrates’ Krapataloi we know about Aeschylus’ presence thanks to a single witness, a scholion on Aristophanes’ Peace (fr. 100 K.–A.). The fact that no witness mentions Sappho's presence in the Miners (a play of which we have just two substantial fragments) cannot therefore be considered as a cogent objection to the identification proposed here.

The identification of ‘character A’ with Sappho, rather than with some figure influenced by the Sapphic tradition, seems compelling. Not only is Sappho very well known for her fatal dive into Tartarus. Several of her fragments suggest a vision of the poetess's privileged position in the Underworld. Moreover, almost all of the revenants of Old Comedy are, in fact, poets (with a very small minority of politicians, as in Eupolis’ Demoi and, perhaps, Taxiarchoi).Footnote 39 And in this category it would be very difficult to find a better alternative to Sappho.

3. Acherusian vegetation

The content of the two lines uttered by ‘character B’ in fr. 113 is not the only clue suggesting a link with Sappho in what remains of the comedy.Footnote 40 The only other fragment of this comedy containing more than a single word, fr. 114 K.–A., from a lyric portion of the play, provides a description of individuals walking within a landscape of blooming vegetation:

These words were probably sung by the chorus, and it has been very reasonably assumed that the landscape described here was the place where the blessed dwell, where flowering meadows are a common topos in literary representations.Footnote 42 Within these topical coordinates, however, two elements point decidedly towards Sappho. The first is the mention of the ‘chervil’ (ἄνθρυσκον/ἔνθρυσκον), a very rare term in poetry that, apart from an occurrence (with the spelling ἔνθρυσκον) in Pherecrates himself (fr. 14 K.–A.) and, probably, in Cratinus fr. 105.6 K.–A. (within a list of flowers used for crowns), has a precedent only in Sappho fr. 96, in the famous description of the moonlit landscape within a simile (ll. 12–14):Footnote 43

Even more interesting is the presence in this context of the terms (not reciprocally linked, but in close proximity) λωτοφόρῳ (‘rich in lotus’) and δροσώδη (‘dewy’), which can be read as an echo of the λωτίνοις δροσόεντας [ὄ]χ[θ]οις, the ‘the dewy banks, covered in lotus’, of Acheron, that Sappho, in her desire to die, longs to see in fr. 95 (transmitted by the same parchment as fr. 96):Footnote 44

This is yet another tessera contributing to my argument that ‘Sappho’ in this play was not just an intertextual reference but a central topic and, arguably, a stage character, playing an important role in the construction of the image of the Underworld.

4. Sappho in the Underworld

Even allowing that most of the elements of the description of the Land of Cockaigne in the Pherecrates’ passage are to be read as variations on a well-established comic topos, we should pay due attention to the fact that there are, in our extremely lacunose corpus, several elements in Sappho's own texts that may contribute to understand the reasons of her choice as a herald of a blessed afterlife.

The fragmentary nature of these texts requires, of course, some caution in their interpretation. However, notwithstanding some recent attempts at playing down their import,Footnote 46 I think that there should be no substantial doubt that they, at the very least, suggest Sappho's peculiar, positive vision of her destiny in the Underworld. This is not to say, however, that the surviving texts should be read as the expression of a group of initiates, or as reflecting mystery cultic practices.Footnote 47

In fr. 95, which we have just examined, a character (probably Sappho herself), persona loquens in the song, in a moment of discomfort expresses her wish ‘to see the dewy banks of Acheron, covered in lotus’, in terms that clearly present such vision as providing relief and consolation, thus innovating upon epic models.Footnote 48 In two other fragments, 55 and 65,Footnote 49 the text describes a condition of fame (of the poetess herself) or of lack of fame (of a woman she criticises) that is going to continue ‘even in Hades’ or ‘even on Acheron's banks’.Footnote 50 The clear implication is that Sappho reckons herself among the individuals who will enjoy the effect of fame even in the Underworld.Footnote 51 A situation in which Sappho enjoys even in Hades, along with Alcaeus, the admiration of her audience is indeed depicted by Horace in Carm. 2.13.29–30 utrumque sacro digna silentio | mirantur umbrae dicere, ‘the shades admire both of them while they recite poems worth of a sacred silence’. In a Sapphic fragment, which in a Ptolemaic papyrus precedes the poem beginning with lines 11ff. of fr. 58 (P.Köln. inv. 21351 + 21376), a badly damaged textual sequence suggests a comparison between the condition of the poetess ‘now on earth’ (l. 6) and that ‘under the earth’ (l. 4).Footnote 52 In the same context the text mentions the fact that ‘she enjoys a befitting privilege’ (ἔχοισαν γέρας ὤς ἔοικεν, l. 5). The fragmentary state of the text does not allow absolute certainty, but everything leads us to think that, as in Horace, the poetess did envisage a continuation of her musical and poetic practice in the Underworld.Footnote 53 A musical performance in the Underworld, or at least related to the Underworld, seems to be alluded to also in a late third-century epigram by Dioscorides, where Sappho is imagined as performing a thrēnos for Adonis together with Aphrodite: ‘or, while performing a dirge together with Aphrodite, who mourns the young offshoot of Kinyras, you look at the sacred grove of the blessed’ (ἢ Κινύρεω νέον ἔρνος ὀδυρομένῃ Ἀφροδίτῃ | σύνθρηνος μακάρων ἱερὸν ἄλσος ὁρῇ, AP 7.407.7–8 (epigr. 18 HE)).Footnote 54

The much-debated fr. 150, addressed by Sappho to her daughter, should be read against the background of the elements examined above:

To say that the funereal song should be banished from the house of the poets (in the sense, that is, that one should not sing such a song for them: the fact that on other occasions poets should or could compose funereal songs for others is not at issue here) is clearly a paradoxical statement that scholars have attempted to neutralise in various ways, adding more or less arbitrary qualifications (of mode, of time, of place) for the performance of such a funereal song,Footnote 55 qualifications, however, absent in the text, and whose casual omission is made unlikely by the context itself of the quotation.Footnote 56 Barring contrary evidence, our source attributes to Sappho an absolute refusal of a funereal song for the servants of the Muses. And this is clearly because, in contrast to what one can imagine for common mortals, for whom death is naturally evil,Footnote 57 the poetess envisages for herself (exactly qua poetess) a privileged existence in the Underworld, where she would have continued to compose and perform songs, enjoying the admiration of her audience, as suggested also by the fragments examined above, and by Horace's vision.

5. Returns of Sappho

With the exception of Pherecrates’ Miners (if my argument holds), and of the potential clues in the iconography of the Porta Maggiore hypogaeum, no ancient document offers glimpses on the ultimate fate of Sappho after her dive from the Rock of Leucas. Death or liberation from her sufferings? Sappho's Epistle, for obvious reasons, stops immediately before the last fatal decision. Ovid's friend, the poet Sabinus, author of the lost poetic replies to the Heroides, must have envisaged a happy ending, as testified by Ovid himself in a famous and tormented passage of his Amores (2.18.34 dat uotam Phoebo Lesbis amata lyram, ‘the Lesbian one, having become the object of love, gives to Phoebus the lyre she had promised as a vow’). The outcome here did not involve death, or deliverance from love, but Sappho's dedication of her lyre, ex uoto, to Apollo, out of gratitude for her now requited love with Phaon (cf. Rosati (Reference Rosati1996)). Her fatal leap, however, was to become the motif that more frequently marked Sappho's reception from the Renaissance onward. Even if only for the sake of providing a satisfying narratological denouement, the riddle of its outcome had to be faced and solved.

To my knowledge, one of the earliest modern representations of Sappho's suicide is that found among the illuminations (attributed to the circle of Jean Pichore) that adorn a copy of the late fifteenth-century French translation of the Heroides by Octovien de Saint-Gelais in fol. 197v of the manuscript Parisinus Fr. 874, produced towards the end of the first decade of the sixteenth century at Rouen, in the milieu of Cardinal Georges d'Amboise (Fig. 3). The image of the woman, chastely dressed from the top of her head to the tips of her feet, falling on the ground (not into the waves), with a rivulet of blood, leaves no doubt about the outcome of her decision. It would be hard to reconcile this iconography with the character of the sexually outspoken poetess in the Ovidian Epistle. This manuscript features some peculiar prose introductions to the Epistles, some of which situate the events in Normandy (cf. Durrieu and Marquet de Vasselot (Reference Durrieu and Marquet de Vasselot1894) 14–15; Brückner (Reference Brückner1989)). In the prose introduction to her Epistle, Sappho is presented as a 24-year-old widow, ‘royne de Pirnance’, discoverer of music and instruments, who falls in love with Phaon, the already-married 28-year-old son of a rich Sicilian merchant, who has arrived with his ship in her port, in a city called ‘Tollo’.Footnote 58 It does not seem to have been noticed that in this manuscript the French text of Sappho's Epistle all too significantly modifies the gist of the original translation of de Saint-Gelais, in a way that makes its character much more compatible with her visual representation. Its text, for example, has eliminated all references to Sappho's earlier homosexual loves. Lines 15–20 of the Latin Epistle refer to Sappho's rejection of her previous female loved ones after she fell in love with Phaon. In all the other manuscripts I have consulted,Footnote 59 and in the early printed editions which I was able to access, these lines are rendered, with a certain degree of looseness, and with several problems regarding the interpretation of the Greek proper names, but without altering their substance, in eleven French lines, including a mention of ‘les trois pucelles que j'ay si fort aimée’ and of ‘Atthis si belle et que tant fort valoit’, who ‘plus ne me plaist ainsi qu'elle souloit’. In Fr. 874, on the other hand, the whole section is rewritten and slightly abridged (it corresponds to only seven lines in the French text) in such a way as to delete any possible allusions to homosexual inclinations.Footnote 60

Figure 3. Parisinus Fr. 874, fol. 197v. Source: Bibliothèque national de France, Département des manuscrits

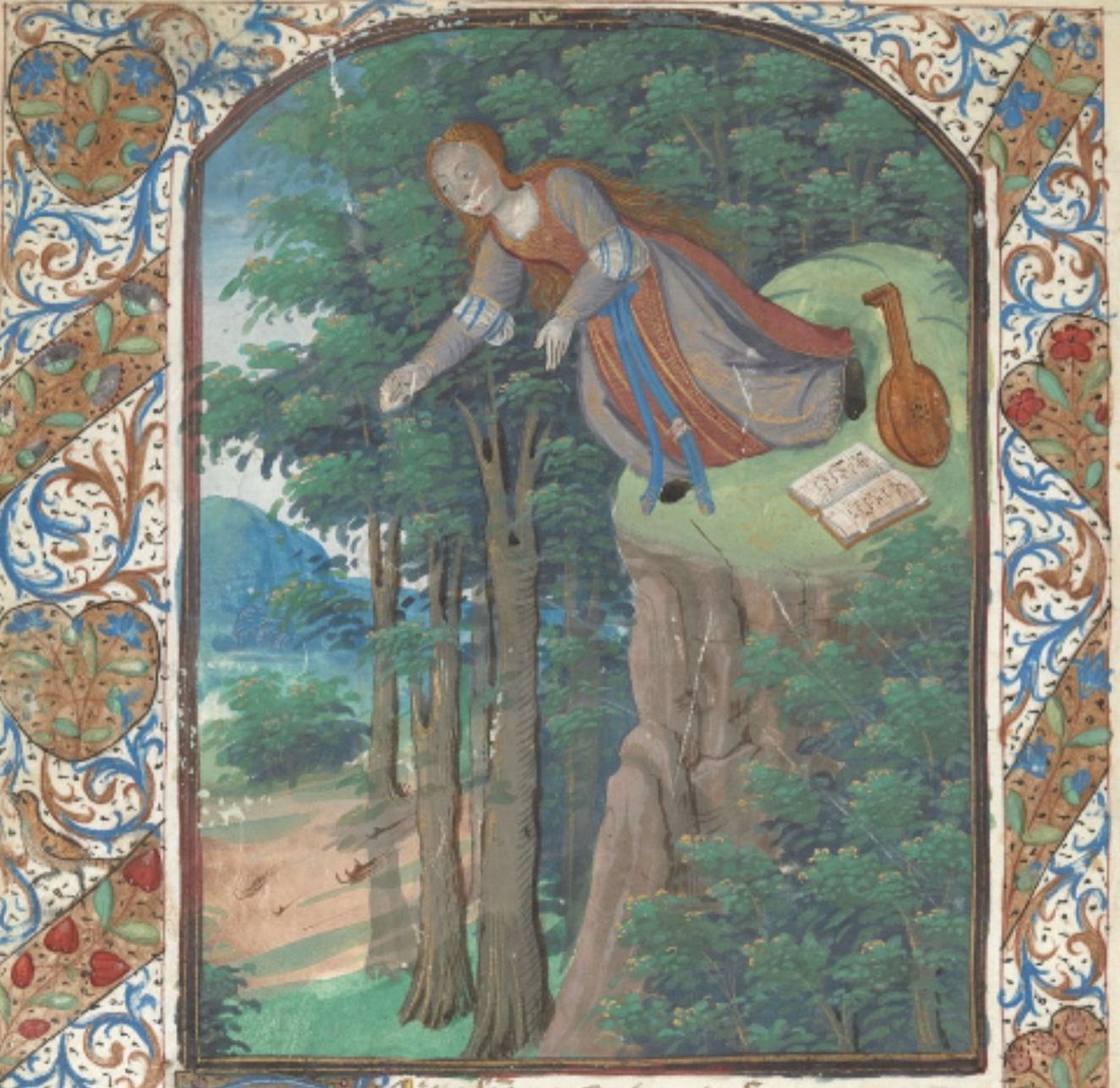

Two other manuscripts of the translation, London, British Libr., Harley 4867 and Oxford, Balliol College Libr., 383 offer a (slightly earlier, probably late fifteenth-century) representation of Sappho immediately before her leap (the Balliol manuscript, Fig. 4) or in the act itself of leaping (the Harley manuscript, Fig. 5).Footnote 61 In both cases the image is remarkably different from that of Paris, BnF, Fr. 874: Sappho is not veiled and has with her signs of her poetic/music activity (a lute and a book in the Harley manuscript; a lute and a harp in the Balliol manuscript, which also features a stream of water – a river, apparently, not the sea – under the rock). In neither case is there any hint at the final outcome of her leap. The representations in these manuscriptsFootnote 62 precede by very few years the entirely different Sappho of Raphael's Parnassus in the Stanza della Segnatura (1510–11), which also (albeit in a very different way) reflects the legacy of the Ovidian Epistle if, as it has been convincingly assumed, the roll with her name the poetess holds in her left hand is to be interpreted as the famous signature/name of the Epistle itself.Footnote 63

Figure 4. Oxford, Balliol College Libr., 383, fol. 167v. Reproduced by permission of the Master and Fellows of Balliol College, Oxford

Figure 5. British Library, Harley 4867, fol. 177v. Reproduced by permission of the British Library

The difference from the illumination of the French Heroides is not only a matter of classical sensuousness: in representing Sappho on his Parnassus, Raphael effectively anticipates the sublimation of her worldly suffering resulting in the triumph of poetry. When, in fact, Sappho entered the narratological engine of more complex constructions, the suspended outcome of the Heroides tradition was bound to become a problematic dénouement, and the heroine's reaching a state of liberation or even apotheosis is revealed as an almost unavoidable solution allowing the granting of a happy ending to the story.

The first ‘literary’ work, to my knowledge, that moves clearly in this direction is the opéra-ballet Le triomphe des arts, with a libretto by Antoine Houdar de la Motte and music by Michel de la Barre, performed at the Académie Royale de Musique on 16 May 1700.Footnote 64 Its second entrée has as its theme the Triumph of Poetry exemplified by Sappho who, made desperate by Phaon's rejection, reacts, once again, with her suicidal move, jumping down from the Rock. In Scene vi a repenting Phaon mourns her fate and asks the music to cease, but Neptune informs him that the poetess has become a goddess, one of the Muses: ‘Cesse de plaindre une déesse: | Sapho prend sa place en ce jour | entre les filles de mémoire. | Le Ciel qui prend soin de sa gloire | veut l’égaler a son amour.’ Houdar de la Motte had no ancient precedent for this narratological solution (the only parallel being the Greek epigrams where Sappho is presented as the tenth Muse), and in his introductory notes defends the innovative character of his choice, even regretting that he did not give more space to a proper representation of the welcome of Sappho on Parnassus.Footnote 65 This absence of precedent is made good for in Vénard de la Jonchère's Sapho (1772), where the poetess is the victim not only of Phaon's fickle behaviour but also of Venus’ scheming against her. In Act ii, Scene vii, in her despair Sapho throws herself from the Rock of Leucas, with an address to Apollo. The god rescues the poetess, bringing her to Parnassus, where she is welcomed by the Muses and rescued, once again by Apollo, also from the menace of Time.

It is against the background of this well-established eighteenth-century tradition of Sappho's apotheosis, which did not entail a properly tragic twist, that in the nineteenth a tradition emerges which attributes to Sappho a self-consciously heroic dramatic character, with F. Grillparzer's Sappho (performed on stage in 1818). In this play, the superhuman poetess, yet again disappointed by Phaon, moves from a Medea-like revengeful fury to the realisation that she does not in fact belong to the human world, where she will never be able to find happiness, but to that of the gods. This is a recurrent motif in the whole drama, whose final consequence is Sappho's leap from the Rock of Leucas, as a return to her divine status: Act iii, Scene ii, ll. 947–54 ‘Hier ist kein Ort für mich als nur das Grab. | Wen Götter sich zum Eigentum erlesen | Geselle sich zu Erdenbürgern nicht … Von beiden Welten eine muss du wählen. | Hast du gewählt, dann ist kein Rücktritt mehr’; Act v, Scene iii, l. 1722 (Phaon) ‘Zeig dich als Göttin! Segne, Sappho! segne!’; ll. 1727–9 ‘Mit Höhern, Sappho, halte du Gemeinschaft | Man steigt nicht unbestraft von Göttermahle | Herunter in den Kreis der Sterblichen’; l. 1783 ‘Den Menschen Lieb, und den Göttern Ehrfuhrcht’ (a line repeated by Sappho in her very last words, Act v, Scene vi, ll. 2025–8); Act v, Scene vi, ll. 2041–2 (Rhamnes) ‘Es war auf Erde ihre Heimat nicht | Sie ist zurückgekehret zu den Ihren’ (the drama's last words).Footnote 66 Along similar lines we should read also the interpretation of Sappho proposed in J. J. Bachofen's Mutterrecht (1861), where Sappho is seen as the priestess of the great mother-goddess, identified with Aphrodite: ‘So … umschliesst Sappho in der Welt ihrer Gefühle alle Seiten der Göttin, der sie dient, mit welcher sie daher auch in der Volkstradition von dem jetzt menschlich gedachtet Phaon und dem Leukadischen Sprung zu Einer Gestalt verschmolzen erscheint.’Footnote 67

This is not, however, the only way in which Sappho's fate was presented in the nineteenth century. It is easy to compare and contrast Grillparzer's apotheosis with the stark refusal of any possible consolation in Leopardi's Ultimo canto di Saffo (1822), where the poetess imagines herself in a bleak Underworld (‘rifuggirà l’ignudo animo a Dite’, l. 56; ‘e il prode ingegno | Han la tenaria Diva | E l’atra notte, e la silente riva’, ll. 71–2, the poem's final lines). All of this reflects Leopardi's own outlook and can be contrasted with Sappho's actual terms of representation of the Underworld, described above (pp. 15–17). In particular it radically reverses the description of the dreary destiny of the soul of the woman who does not partake in the roses of Pieria (fr. 55).Footnote 68 In this Leopardi had an interesting antecedent in Vincenzo Maria Imperiali's Faoniade, a collection of hymns and odes of ‘Saffo’ (presented as ‘translated’ from Sappho) arranged as part of a biographical trajectory and published for the first time in Venice in 1780, and then several times well into the nineteenth century. In the last ode of the second part, titled A Vow to Apollo, Imperiali's Sappho envisages two possible outcomes of her leap. The first one is explicitly based on what is now our fr. 55, but transforms Sappho's address to another woman into a self-address:

This is followed by an alternative of salvation, even if Imperiali notes that one should believe that in Sappho the fear of death prevailed over the hope of salvation. The latter option is not even envisaged by Leopardi,Footnote 70 who, by contrast, anticipates a theme that was to emerge from a later papyrus discovery, i.e. that of Sappho's longing for her own death as an escape from her suffering (which we examined above with regard to fr. 95).

In any case, Sappho's apotheosis and the recognition of her divine nature as envisaged by Grillparzer show obvious limits if we are to move from the development of an (almost mythological) character to that of the reception of a poetic tradition. In later tradition Sappho comes back from her suicidal leap as the ambiguous image of a corpse, or as the symbol of a failure. In Lesbos, a poem first published in 1850Footnote 71 before briefly finding place within Les Fleurs du mal in 1857, soon to be expelled from the collection in the same year as one of the ‘damned poems’, Baudelaire offers an idealised vision of the island, as a land of full love not subject to the judgement of human or divine morality, and imagines the poet as charged with the mission to wait for the return of Sappho's corpse (ll. 46–55, 71–5):

Lesbos and the poet wait for Sappho's return, in the expectation that it may bring again to the island the miracle of the arrival of Orpheus’ severed head.Footnote 72 This image contributes to the reincarnation of an ambiguous poetic tradition where the object of adoration is, in fact, not a goddess but a corpse. It is a very powerful image whose profound ambiguity affects not only Baudelaire's attitude towards female homosexuality (as shown, among others, also by two other poems of the series Femmes damnées – both originally in the section Fleurs du mal together with Lesbos, and with one of them, Delphine et Hippolyte, also ‘damned’ and ejected from the first edition of the collection – that represent it under a strongly negative perspective), but also his vision of the relationship with the ancient, classical tradition. Between Lesbos’ first publication and that of Les Fleurs du mal Baudelaire had published the essay L’école païenne (in La semaine théâtrale, January 1853) with its resounding rhetorical question: ‘Qui nous délivrera des Grecs et des Romains?’ There, exalting a collection of cartoons by H. Daumier titled Histoire ancienne, Baudelaire comments:

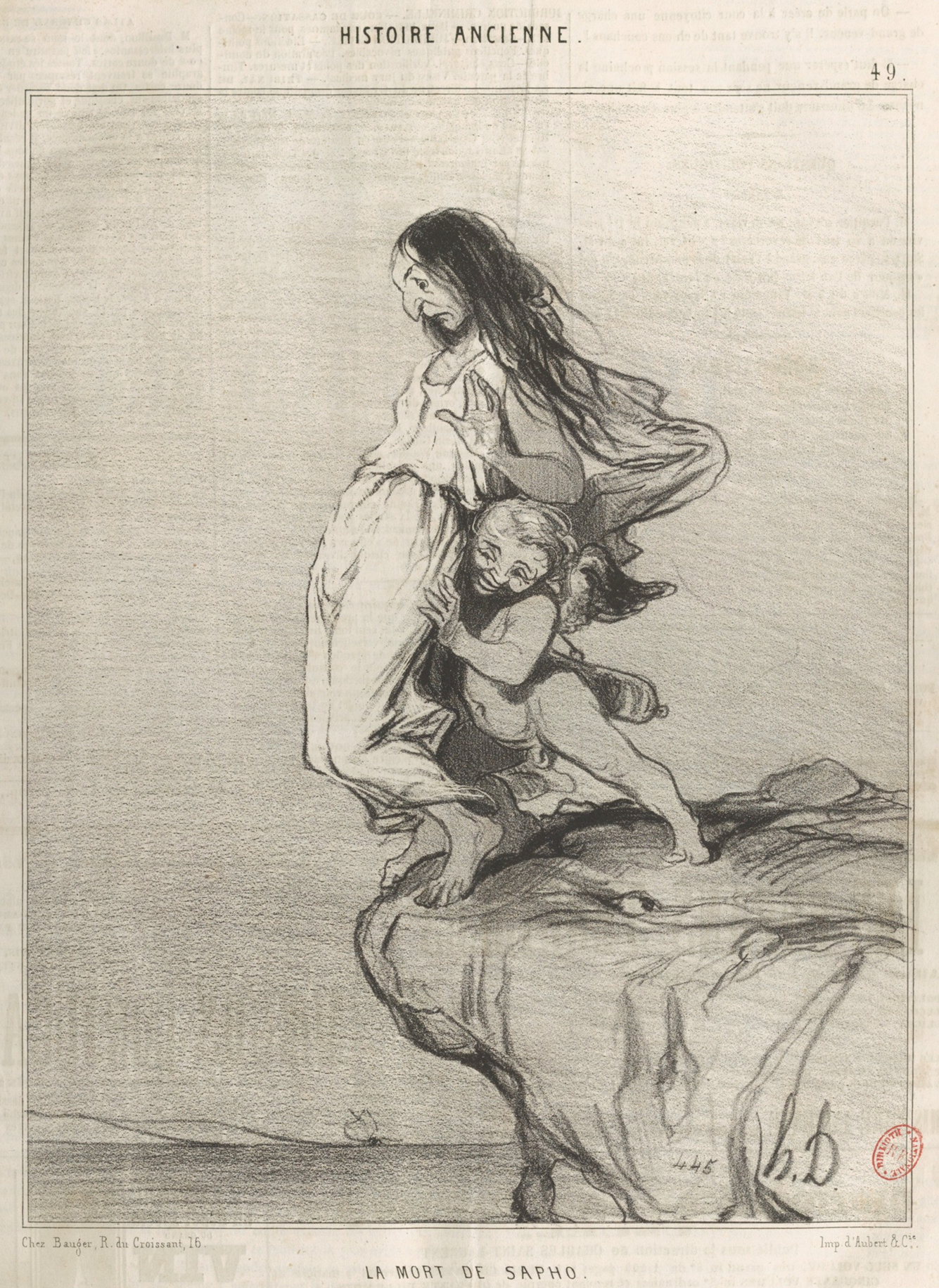

Daumier s'est abattu brutalement sur l'antiquité et la mythologie, et a craché dessus. Et le bouillant Achille, et le prudent Ulysse, et la sage Pénélope, et Télémaque, ce grand dadais, et la belle Hélène, qui perdit Troie, et la brûlante Sapho, cette patronne des hystériques, et tous enfin nous apparurent dans une laideur bouffonne qui rappelait ces vieilles carcasses d'acteurs classiques qui prennent une prise de tabac dans les coulisses. Eh bien! j'ai vu un écrivain de talent pleurer devant ces estampes, devant ce blasphème amusant et utile. Il était indigné, il appelait cela une impiété. Le malheureux avait encore besoin d'une religion. [Emphasis added]

The reference to Sappho in L’école païenne was inspired by a cartoon where the poetess, aged, unattractive and with almost masculine traits, is pushed, obviously against her will, down from a rock by a little Cupid (Fig. 6). The inverted similarity with the scene in the apse of the Porta Maggiore Basilica (obviously unknown to Daumier: Fig. 1) is remarkable.Footnote 73 The use of the terms ‘old carcasses’ and ‘blasphemy’ establishes a clear potential link (with a radical inversion of meaning) to the ‘adored corpse’ of Sappho, and the ‘blasphemy’ that caused her death in Lesbos (‘celle qui mourut le jour de son blasphème’, l. 70; cf. also l. 66).

Figure 6. H. Daumier, La mort de Sappho, published in Le Charivari, 4 January 1843. Source: Bibliothèque national de France

This is a very good example of the ‘contradiction’ typical of the ideology of the Second Empire, which Walter Benjamin saw as one of Baudelaire's key traits: ‘The same traits are found in Baudelaire's theoretical writings. He usually presents his views apodictically. Discussion is not his style; he avoids it even when the glaring contradictions in the theses he continually appropriates require discussion.’Footnote 74 DeJean ((Reference DeJean1989) 270–1) reads this contradiction (without exploring the parallels I have highlighted in the text above) as a sort of marketing strategy to mark a difference from other contemporary literary and dramatic Sapphic creations. This, however, runs the risk of concealing the importance of the profound contradiction we find inside Baudelaire's own work (note that he published Lesbos both before and after his 1853 essay). The essay's formulation subverts in a very conspicuous way that of Baudelaire himself in his earlier poem.

The ambiguity of the figure of the corpse/carcass intersects in many ways with the figure of Sappho in Baudelaire. It will be useful to follow it by taking into account Lesbos (now usually read as the second poem of Les épaves) in its original and intended relationship with other poems that appeared in the same section of the first edition of Les Fleurs du mal in 1857. The poem, number lxxx in the whole collection, was the third in its second section, also called Fleurs du mal. In the original sequence of this section, it was preceded by the poem Une martyre – whose title would have reflected on Lesbos’ ‘eternal martyre’ (ll. 26, 30) – prominently featuring the voyeuristic description of a female corpse, that of a woman beheaded in her apartment by an unknown lover/murderer. Her ‘cadavre impur’ (l. 49) thus originally immediately preceded Sappho's ‘cadavre adoré’ (Lesbos v. 54). Even more crucially linked to Lesbos is another poem, Un voyage à Cythére, number lxxxviii in the 1857 edition, and the penultimate in the same section. This poem, which survives also in two manuscript versions, one of which dated January 1852, was first published in 1855 but probably goes back, like Lesbos, to the 1840s. It was inspired by an 1844 prose piece of Gérard de Nerval, taking the cue from his journey in the region, with an imaginative description of the abysmal gap separating the fantasy of the classicising journey to Cythera from the grim reality of Cerigo (the island's modern, Venetian, name), a barren land whose sight is for the narrator dominated by an imposing tripartite gallows from which a human corpse hangs.Footnote 75 The contrast between idealising classical memory and the rotting carcass is graphically intensified in Baudelaire's poem, in a way that makes its parallelism to Lesbos’ Sappho unmistakeable. Lines 9–16, a hymn-like address to the island of Venus, and lines 21–4, evoking (in contrast) the image of a temple scene, recall in their topicality analogous sections of the address to the island in Lesbos:

The longing for the ancient, feminine ritual scene, however, is substituted in this poem by the spectacle of the hanged corpse of an inhabitant of the island (ll. 41–4):

The insult of the capital execution and the public display of the rotting carcass hanging from the gallows is here explained as an expiation for the island's ‘infamous cults’,Footnote 76 in a way that clearly is meant to mirror the representation of Sappho's impiety (‘impiété’, Lesbos l. 69) as the cause of her death: ‘qui mourut le jour de son blasphème … insultant le rite et le culte inventé’ (Lesbos ll. 66–7).Footnote 77 The narrating voice of the ‘poet’ closes the poem by fully identifying himself with this rotting carcass: the vision of the ancient ritual is cancelled by ‘un gibet symbolique ou pendait mon image …’ (l. 58).Footnote 78 Here we find, again, the contrast between the mirage of the fullness of lost, sensuous, feminine rituals and its transformation, as the result of an act of impiety, into the vision of a corpse. The corpse survives, therefore, both as longed-for ‘cadavre adoré’ and as a rotting carcass (with which nevertheless the narrating voice of the modern poet of Un voyage à Cythére identifies).Footnote 79 The ambiguity of the two sides of Sappho's reception shows how her fatal leap can shift, once again, from being the symbol of a promise to that of a failure.

The two themes, that of the corpse of the drowned poetess, and that of her rejection in favour of a poetry not bound anymore by the constraints of the past, emerge with clarity in one of the first poems of the American poet Muriel Rukeyser, Poem out of Childhood, published in her first book, Theory of Flight (1935). It will be useful to quote the end of its first stanza:

Sappho becomes here the image of death by drowning, of a floating corpse that will not land anywhere,Footnote 81 ‘trailing along Greek waters’, while innumerable seas open themselves to the eye of new generations. In the following year, 1936, Rukeyser would leave the United States for the Spain of civil war.

That same year, 1936 (the book had been completed already in 1935), saw the publication of one of the greatest and subtle re-creations of Sappho in modern and contemporary literature, within the collection Feux of Marguerite Yourcenar (who in 1939 will travel in the opposite direction, towards the United States, leaving Europe on the brink of a war).Footnote 82 The short prose poem that closes the collection (Yourcenar (Reference Yourcenar1936)) bears the title Sappho ou le suicide. It is a text too rich to be more than very lightly touched upon here. Yourcenar's Sappho is a contemporary character, a circus acrobat ‘comme aux temps antiques elle était poétesse, parce que la forme particulière de ses poumons l'oblige à choisir un métier qui s'exerce à mi-ciel’, and belongs to ‘ce group de fantômes en vogue qui planent sur le villes grises. Créature aimantée, trop ailée pur le soil, trop charnelle pour le ciel.’ As noted by DeJean ((Reference DeJean1989) 295–6), here Baudelaire is a crucial reference point: in the scene Le vieux saltimbanque, in his collection of prose poems Le spleen de Paris (1863), Baudelaire sees an old derelict acrobat as the figura/figure of the old ‘man of letters who survived his generation, for whom he was a brilliant entertainer; of the old poet, without friends, without family, without sons, degraded by his misery and by his audience's ingratitude’.Footnote 83

Yourcenar's Sappho, just as that of Grillparzer, is trapped between two worlds, heaven and earth, but, in contrast to her Romantic incarnation, she will not have the consolation of a final redeeming apotheosis. Her suicide itself is destined to failure. ‘Mais ceux qui manquent leur vie courent aussi le risque de rater leur suicide.’ The acrobat's fall is intercepted by the machineries of the circus. ‘Étourdie, mais intacte, le choc rejette l'inutile suicidée vers les filets où se déprennent des écumes de lumière; les mailles ploient sans céder sous le poids de cette statue repêchée des profondeurs du ciel. Et bientôt les manœuvres n'auront plus qu’à haler sur les sable ce corps de marbre pâle, ruisselant de sueur comme un noyée d'eau de mer.’ Not an apotheosis, but not even a corpse: a statue condemned to go on living.Footnote 84

6. Conclusions

Among the texts we have examined above only one, that of Yourcenar, might have been composed in awareness of the representation of Sappho's leap in the Porta Maggiore Basilica. It is not at all inconceivable that, trained as a classicist as she was, Yourcenar might well have been familiar at least with Carcopino's monograph. It is possible that another source of influence for her would have been Strabo's passage, where, after a list of the famous and less famous characters who dived from Cape Leucas, we find the description of a local rite in which the leap involves real scapegoats (10.2.9):

ἦν δὲ καὶ πάτριον τοῖς Λευκαδίοις κατ' ἐνιαυτὸν ἐν τῇ θυσίᾳ τοῦ Ἀπόλλωνος ἀπὸ τῆς σκοπῆς ῥιπτεῖσθαί τινα τῶν ἐν αἰτίαις ὄντων ἀποτροπῆς χάριν, ἐξαπτομένων ἐξ αὐτοῦ παντοδαπῶν πτερῶν καὶ ὀρνέων ἀνακουφίζειν δυναμένων τῇ πτήσει τὸ ἅλμα, ὑποδέχεσθαι δὲ κάτω μικραῖς ἁλιάσι κύκλῳ περιεστῶτας πολλοὺς καὶ περισώζειν εἰς δύναμιν τῶν ὅρων ἔξω τὸν ἀναληφθέντα.

It was an ancestral custom among the Leucadians, every year at the sacrifice performed in honour of Apollo, for some criminal to be flung from this rocky lookout for the sake of averting evil, wings and birds of all kind being fastened to him, since by their fluttering they could lighten the leap, and also for a number of men, stationed all round below the rock in small fishing boats, to take the victim in, and, when he had been taken on board, to do all in their power to get him safely outside their borders.Footnote 85

Just as the ‘victims’ in Strabo's rite face the leap tying to themselves wings and birds, so Yourcenar's acrobat is ‘drapée de longs peignoirs qui lui restituent ses ailes’ and keeps in her chests ‘de débris d'oiseaux’. And, just as the indicted individuals forced to jump in Strabo (but, according to Photius, Lex. s.v. Λευκάτης, those who threw themselves down from the Rock were actually priests, ἱερεῖς; Servius on Aen. 3.279 uses the expression se auctorare suggesting the activity of individuals who would endanger their life for a wage, just as gladiators, or acrobats),Footnote 86 Yourcenar's Sappho is eventually rescued as a drowned body, but her destiny is unavoidably to go on living, as a pariah/outsider, ‘beyond borders’ (τῶν ὅρων ἔξω).Footnote 87

Several of the options we have examined derive from the necessity to find narratological solutions to events developed around an iconic character who is the object of continuous reshaping, in ways that are sometimes close to stereotypes, but often reveal previously unsuspected potentialities. This has been Sappho's destiny since even before there was an ‘edition’ of her songs. This urge to reimagine Sappho's ‘afterlife’ opened the path, in antiquity and beyond, to a series of visions of the poetess as harbinger of an eschatological message, or as an exemplary failure, an image variously transformed, deformed and simplified, but returning, again and again, in new creative incarnations of one of the most powerful icons of ancient Greek poetry's legacy.