In his 2007 book The Total Work of Art: from Bayreuth to Cyberspace, Matthew Wilson Smith compares two sites of nineteenth-century performance: Wagner’s timber-framed theatre in Bayreuth, which opened in 1876 for the premiere of the complete Ring cycle, and Joseph Paxton’s glass-and-iron Crystal Palace, erected in London’s Hyde Park to welcome over six million visitors to the Great Exhibition of 1851.Footnote 1 These competing festive spaces – one in a neglected German town and the other in a global hub of empire – point to what Smith calls the ‘divided form’ of the Gesamtkunstwerk (total work of art).Footnote 2 If the Great Exhibition projected a vision of totality through the outward celebration of technology and industry, Wagner’s Bayreuth theatre amounted to ‘a pseudo-organic form’ characterised by a concealment of the means of production in the service of an immersive theatre of illusion.Footnote 3 Smith uses these two competing sites to tell a story about the enduring legacy of the total work of art for modern and postmodern performance and mass media.Footnote 4 However, and as this article will demonstrate, the opposition between the Bayreuth Festspielhaus and the Crystal Palace also points to an alternative history of Wagnerian performance in the mid-nineteenth century, one in which the Romantic ideal of artistic integration in a provincial theatre was entangled with the rise of monumental buildings for orchestral music in an industrial city.

A year after the premiere of the Ring cycle, Wagner resumed his career as a touring composer-conductor and refashioned his Bühnenfestspiel (stage festival play) for Victorian concert life, preparing six programmes to be performed by a vast orchestra and guest singers at the Royal Albert Hall, newly opened in South Kensington near the original site of the Great Exhibition. Having previously appeared in the capital as guest conductor of the Philharmonic Society at the Hanover Square Rooms over two decades earlier, Wagner this time joined a troupe of celebrated Bayreuth musicians and singers, including conductor Hans Richter, violinist August Wilhelmj (concertmaster of the Bayreuth orchestra) and the star singers Amalie Materna, Carl Hill, Georg Unger and Friederike Sadler-Grün. Whereas the more modestly sized Hanover Square Rooms (constructed in 1776 with a capacity of five hundred) still reflected an economic model of elite subscription concerts, the Albert Hall boasted a volume of three million cubic feet and an initial capacity of at least 7,000, making it the largest auditorium in Europe at the time of its completion in 1871.

The transfer of the Ring from the specific conditions of the festival theatre to the resonant amphitheatre of the Albert Hall was an initiative born out of financial necessity in the aftermath of the long-awaited staging of the complete cycle. My intention here, however, is not to perpetuate a familiar image of Wagner’s London appearance as an unfortunate detour on the path towards realising his complete works on the Bayreuth stage.Footnote 5 Instead, I seek to re-evaluate the Victorian mass concert as a format for the remediation of music drama, emphasising the dependence of Wagnerism – and concomitant aesthetics of musical idealism – on industrial infrastructures and acoustic environments. While I return to Wagner’s London concerts in the final section of this article, I begin by tracing the origins of the Albert Hall in counterpoint with the evolution of the Festspielhaus. The focal point in the first section is the architect Gottfried Semper, a friend and collaborator of the composer from his Dresden days in the 1840s. Best known at that time as the architect behind the Dresden Hoftheater (1841), Semper played a leading role in the revolutionary uprising of 1849 (he designed the republican barricades), before escaping to London as a political exile.Footnote 6 Semper went on to work as part of the team of designers and architects behind the Great Exhibition and the subsequent South Kensington development, before joining Wagner once again in Zurich and producing plans for a proposed festival theatre in the Munich Glaspalast. Although Semper’s large-scale architectural plans of the 1850s and 1860s remained unrealised, his journey provides a prism through which to trace the shared genealogy of two very different musical buildings.Footnote 7

The second and third sections of the present article turn in more detail to the Albert Hall, focusing on the years surrounding its opening in 1871. In a quest to construct a civic space for public concerts and exhibitions on an unprecedented scale, Victorian engineers sought to recuperate an idealised vision of the classical amphitheatre for the imperial metropolis. Yet the opening ceremony was famously disturbed by loud echo effects, leading many writers to speculate about the need for a rigorous application of acoustic science to musical buildings. A significant voice in these discussions was Henry Heathcote Statham, a professional architect who also worked as music critic for the Edinburgh Review. In an 1872 address to the Royal Institute of British Architects – entitled ‘Buildings Practically Considered in Reference to Music’ – Statham criticised the multi-functional purpose of the Albert Hall and advocated a new kind of concert venue that would facilitate intimate listening to the intricacies of oratorio and symphonic music. Statham went on to intervene in the Wagner debate then dominating periodical discourse on music, countering contemporary writers who sought to promote the composer within the symphonic tradition as the natural heir to Beethoven.Footnote 8 The final section of this article hones in on these Victorian mediators of Wagner’s music and aesthetics, especially the music critic Francis Hueffer (born Franz Hüffer) and the conductor, pianist and writer Edward Dannreuther. During the 1870s these men combined the intellectual diffusion of German musical metaphysics with the practical work of concertising and fundraising, preparing the way for Wagner’s celebrity appearance at the Albert Hall with his Bayreuth entourage.Footnote 9 Much of the critical reception of this event (which was branded the London Wagner Festival) centred around the viability of experiencing the total work of art in concert form: for Wagner’s supporters the pared-back format facilitated an authentic appreciation of the musical drama free of visual accoutrements, while for detractors the concerts amounted to a miscellany of snippets that degraded aesthetic unity. Clearly the London Wagner Festival marked a pragmatic departure from the composer’s ideals about the exemplary performance of the Ring cycle; yet these concerts were also indicative of the emergent mobility of the work in the aftermath of the premiere. As I discuss in the coda, the London Wagner Festival anticipated later, more ambitious attempts to reproduce the Ring for audiences beyond Bayreuth, while the Albert Hall itself functioned as a medium of mass dissemination at the dawn of the recording era.

Wagner, Semper and legacies of the Great Exhibition

In January 1852, three years after fleeing to Zurich in the aftermath of his involvement in the Dresden uprising, Wagner wrote to Franz Liszt in despair at the bleak prospects of mounting a performance of his Siegfried drama. While he dispelled hopes of ever bringing the work to fruition if exiled from his native country, he also made some stipulations about conditions for its potential performance. Above all, he could no longer reconcile his latest work with the public culture of Europe’s industrial cities:

I do not expect its performance, at least not during my lifetime, and least of all in Berlin or Dresden. These and similar large towns, with their public, do not exist for me at all. As an audience I can only imagine an assembly of friends who have come together for the purpose of knowing my works somewhere or other, best of all in some beautiful solitude, far from the thick smoke and disgusting industrial stench of our urban civilization.Footnote 10

In imagining a performance of Siegfried in a secluded location, Wagner was alluding to a prospect already set out in letters to the conductor Theodor Uhlig. If only he could raise ‘10,000 thalers’, he wrote to Uhlig, he would perform Siegfried where he happened to be in Zurich, constructing a temporary theatre made of planks. He would engage the best singers and invite a dedicated audience to join him for this fleeting special occasion.Footnote 11

At the same moment Wagner was denouncing smoke-filled cities as antithetical to his festival concept, his future collaborator – Gottfried Semper – was rebuilding his career in London as a proponent of monumental public architecture.Footnote 12 Exiled in the British capital for five years, Semper published seminal texts in architectural theory and coordinated interior displays for the Great Exhibition. Alongside his practical involvement in the Exhibition, he emerged as a significant commentator on the event, contributing to debates about the legacy of the Crystal Palace with a report entitled Wissenschaft, Industrie und Kunst: Vorschläge zur Anregung nationalen Kunstgefühles bei dem Schlusse der Londoner Industrie-Ausstellung (Science, Industry and Art: Proposals for the Development of a National Taste in Art at the Closing the London Industrial Exhibition). Central to his outlook was the concept of permanent museum collections as a means of educating consumers. Adjoining the idea of the collection with lectures, workshops and awards, Semper envisaged Paxton’s temporary ‘glass-covered vacuum’ transformed into a permanent monument to artistic education in the capital.Footnote 13

Despite calls for the Crystal Palace to remain in Hyde Park, Paxton’s pre-fabricated glass-and-iron structure was dismantled soon after the exhibition ended, and resurrected in Sydenham as an enlarged complex for recreation, entertainment and concerts, opening in 1854. Semper designed the Woollen and Mixed Fabric Court for the Sydenham site and drew up plans for an unrealised Roman-style amphitheatre – originally intended to stand within the central transept as a complement to Matthew Digby Wyatt’s Pompeii court.Footnote 14 In 1853 he was appointed Professor of Metal Manufactures at the School of Design, a position that cemented his professional allegiance with the influential designer and civil reformer Henry Cole. Cole had been instrumental in organising and promoting the Great Exhibition as part of a long-standing paternalistic effort on behalf of the Society of Arts to boost the quality of British manufacturing and reform public taste. In his role as public spokesperson for the Exhibition, he attributed the origins and success of the event to what he saw as Britain’s unique cosmopolitan character, and its new commercial conditions of international free trade. In so doing, he helped to craft an image of the Exhibition as a triumphant display of British exceptionalism on the world stage, an image sustained through much of the official and popular commentary surrounding the event.Footnote 15

The official promotion of the Great Exhibition as a historical watershed on the way to peaceful relations and productive competition has of course given way to divergent contemporary narratives of the event as a political display of British imperialism and globalisation; as a catalyst for Victorian commodity culture; and a glistening allegory for the experience of modernity at large.Footnote 16 Looking beyond the meanings of the Crystal Palace itself, meanwhile, the Exhibition and its contents were instrumental in the development of state-sponsored museums, galleries and expositions as open and public spaces of regulated spectatorship.Footnote 17 Despite the transient nature of the event, it led to a drive among government reformers to build civilising public arenas, collections and institutions within the South Kensington cultural quarter that later came to be known popularly as ‘Albertopolis’. Shortly after the closing ceremony, Cole oversaw the building of a new museum of practical arts, which later became the South Kensington Museum.Footnote 18 Meanwhile, Prince Albert (in his capacity as president of the Royal Commission) proposed investing the approximately £186,000 profit from admission tickets in twenty-two acres on Kensington Gore for the purpose of developing his vision of a complex of cultural institutions dedicated to the public cultivation of the arts and sciences. His concept of such a complex later included a central hall suitable for musical performances and exhibitions, surrounded by shops and flats with museums and art galleries. Initially, Albert’s favoured architect for implementing this grand scheme was Semper. In June 1855, the architect met Cole and the Prince Consort to present elaborate plans and a cardboard model for the proposed School of Design, the South Kensington Museum and a Hall of Arts and Sciences. However, the Board of Trade rejected Semper’s designs as too extravagant, and the concept was set aside in favour of concentrating on the School of Design and the first wing of the South Kensington Museum, designed by the Royal engineer Francis Fowke and opened in 1857.Footnote 19

Following the rejection of both his theatre for the Crystal Palace and his plans for the South Kensington complex, Semper departed London to accept a position as professor at the new Polytechnic Institute in Zurich, from where he began working with Wagner on designs for his festival theatre.Footnote 20 If Wagner had initially conceived of a rudimentary festival site away from encroaching urbanisation, the patronage of Ludwig II in the 1860s resulted in a very different scheme to build a monumental public theatre dedicated to his operas in Munich.Footnote 21 Initially, Ludwig engaged Semper to design a vast permanent theatre in stone. At the same time, a compromise was reached with plans for an amphitheatre to be erected temporarily within the Munich Glass Palace (Glaspalast), an exhibition hall modelled on the Crystal Palace and opened for the First General German Industrial Exhibition in 1854.Footnote 22 But with spiralling costs and growing government controversy over the scale of Ludwig’s investment, the Munich designs never materialised, and Wagner was forced to return to Switzerland. Despite Semper’s extensive efforts to meet the conflicting demands of both composer and patron, his contribution went largely unacknowledged; the project was eventually taken up and reimagined by Otto Brückwald.Footnote 23 By finally settling in Bayreuth, Wagner sought to renew his protest against metropolitan concert life and opera houses as products of bourgeois leisure time, projecting an image of a neglected German town as a renewed site of national heritage and artistic devotion. But while he clung to a Romantic vision of his Ring cycle as recuperating a lost state of nature, the realisation of this experience was conditioned by modern infrastructures and technologies of staging, instrumentation, print media and tourism.Footnote 24 Indeed, the premiere of the Ring in Bayreuth would attract substantial interest from English visitors, prompting press coverage and critical commentary from both sides of the channel about the inaugural festival as a site of cultural consumption for metropolitan tourists.

In London, meanwhile, the prospect of a monumental exhibition hall on the South Kensington estate eventually progressed first under the auspices of the second international exhibition of 1862 and then as a memorial to Prince Albert. Initially, Cole and Fowke imagined a vast, multi-purpose auditorium and exhibition space to accommodate 30,000 people, inspired by Cole’s tours of Roman amphitheatres at Arles and Nîmes in Southern France. After the death of Albert at the end of 1861, plans resurfaced in the somewhat more economical form of a commemorative Hall of Arts and Science.Footnote 25 While the commissioners had put forward a grant of £50,000 towards the building, the absence of parliamentary funds led Cole to initiate a private investor scheme intended to canvass funding from wealthy patrons interested in furthering the arts and sciences, with the added incentive of making a substantial return on their investment. By 1865, having secured the backing of the Prince of Wales, the committee had sold 1,300 advance seats at £100 each to individual patrons for the duration of the 999-year lease. When Fowke died suddenly the same year, the commissioners discussed appointing an architect to take over the design of the building and Cole suggested inviting Semper, whose Dresden theatre had been a source of inspiration.Footnote 26 But once again the commissioners rejected the prospect of a foreign architect, preferring a team of Royal engineers led by Lieutenant-Colonel Henry Scott. On 20 May 1867, a crowd of 6,000 assembled for the laying of the foundation in the presence of Queen Victoria; she announced her wish that the hall should be renamed ‘The Royal Albert Hall of Arts and Sciences’.Footnote 27

Although the Albert Hall originated in proceeds from the Great Exhibition, its elliptical shape and brick-and-terracotta heaviness were far removed from the ethereal fragility and transparent airiness invoked by the original Crystal Palace. And whereas the image of Paxton’s precarious yet imposing glass structure has been lauded as an exceptional anticipation of modernist industrial architecture, the Italianate façade of the Albert Hall is clearly more in keeping with the familiar historicism of Victorian public monuments. According to Marshall Bermann, who interprets the Crystal Palace as an exhilarating symbol of progressive modernity, ‘the bourgeoisie enjoyed the Exhibition, but rejected the building, and went back to building Arthurian railroad stations and Hellenistic banks; in fact, no more genuinely modern buildings would be built in England for another fifty years.’Footnote 28

‘An engineer’s rather than an architect’s building’

Though the differences between the Albert Hall and the Crystal Palace were obvious on the surface, contemporary critics immediately drew parallels between the two buildings in terms of the multiple aims and uses of these glass-covered public arenas of rational recreation and improvement. Several newspapers expressed political concerns about the vested interests involved in erecting another monumental hall with a vague and miscellaneous purpose to rival the palace on Sydenham Hill. The Pall Mall Gazette took aim at the commissioner’s reinvestment of public money from the 1851 Exhibition in the acquisition of private land and property essentially of long-term gain to the aristocracy. That the construction of the Albert Hall had been enabled by a corporate investor scheme – one explicitly promoted by the commissioners on the promise of a handsome return – was a clear indication that the whole design was ‘a little more fit for the Stock Exchange than for the patronage of the heir apparent’.Footnote 29 Meanwhile, a letter to the Daily News voiced scepticism about the epithet ‘Hall of Sciences’, suggesting that the building would more likely amount to a hall of entertainment, ‘nothing more than a Chartered Crystal Palace’. The author of a similar letter to The Times (reprinted in the Musical World) made a further swipe at the aristocratic and corporate interests behind the projected Hall, claiming that ‘one of the 1,000l. purchasers of boxes assured me that he made the investment in the expectation that the Hall would become a fashionable West-end opera, and would ultimately turn out a good speculation’.Footnote 30

The proposed Hall was further reminiscent of Paxton’s structure in as much as it was, in the words of the Pall Mall Gazette, an ‘engineer’s rather than an architect’s building’, reflecting the new means of construction of the industrial age.Footnote 31 The bold vaulted roof (the largest unsupported dome at the time of construction) consisted of two layers of glazing held together by wrought iron arched trusses and supported by girders, enabling both structural stability and a ventilation and heating system. Modelled on the immense single-supported glazed roofs of the recently completed Charing Cross and St Pancras railway terminals, the wrought iron structure of the dome was prefabricated and tested by the Fairbairn Engineering Company near Manchester before being dismantled and transported to London for its dramatic installation (Figure 1).Footnote 32 Seen in this context, the building not only mirrored the aesthetics of the Crystal Palace and other expansive glass-covered public enclosures in mid-Victorian London, but epitomised the acceleration of iron construction and the dominance of engineering over architecture that Walter Benjamin memorably associated with the capitalist modernity of the Paris Arcades. In short, the Albert Hall combined a recuperation of the imperial amphitheatre with the urban transience of the exhibition hall and railway station.Footnote 33

Figure 1. Test construction of the Royal Albert Hall roof in Ardwick near Manchester, 1870. Courtesy of the Royal Albert Hall Archives.

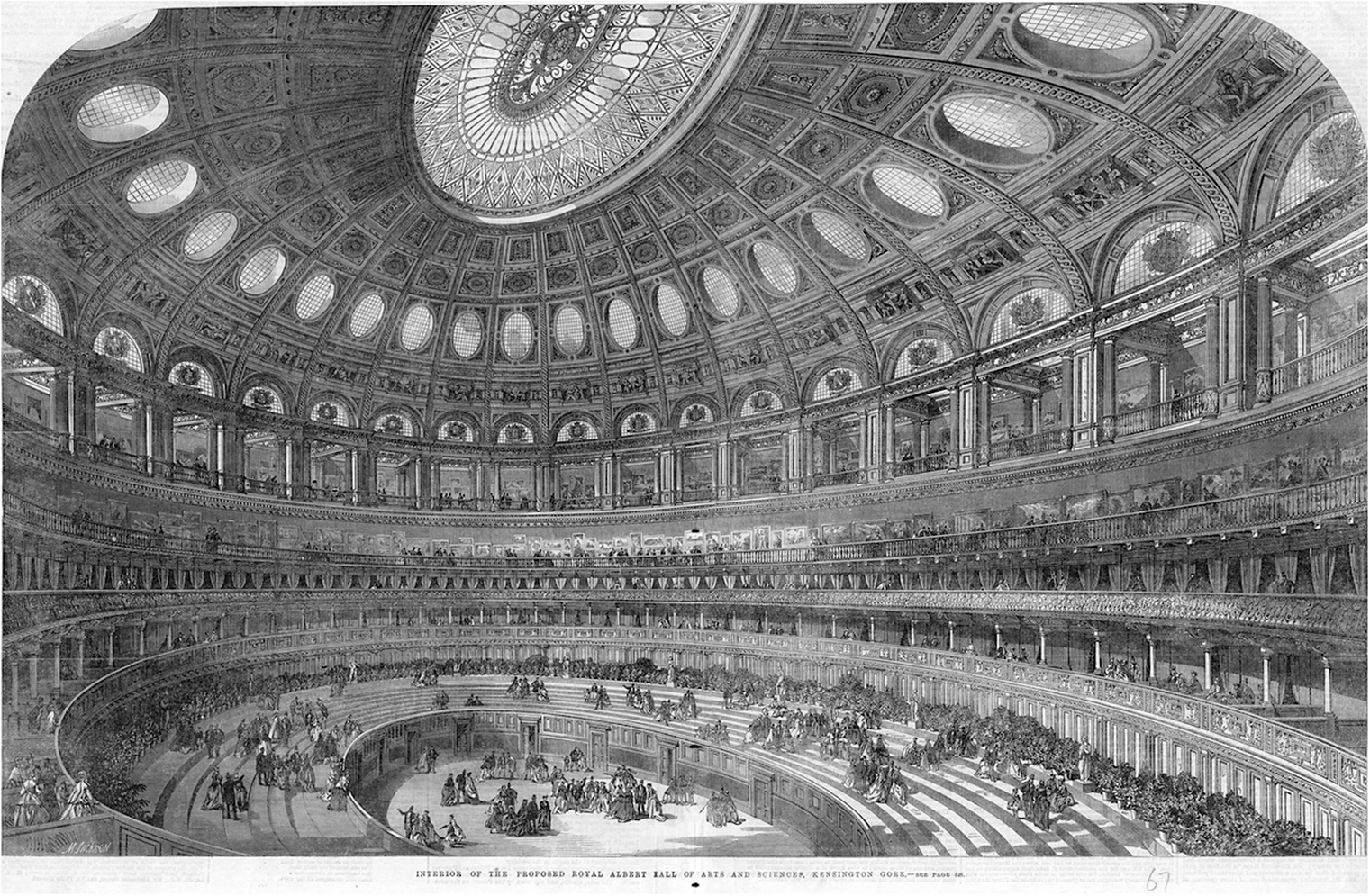

The aspiration to connect an idealised classical past with urban cultural improvement in the present was captured in a full-page engraving of the projected interior of the Hall in the Illustrated London News on the occasion of the laying of the foundation stone (Figure 2).Footnote 34 Viewed from the perspective of the orchestra looking out from the top of the choir stalls, the engraving gives a panoramic view of the interior as a whole, an exaggerated simulacrum of civilised order as perceived from the kind of detached perspective that Michel de Certeau would define as the ‘celestial eye’ of the space planner.Footnote 35 The image encompasses an airy interior illuminated by natural light from above, leading the eye upwards to the glazed roof as the centrepiece of an extravagant and ornate dome. Within this panoramic ideal the well-dressed figures below are not seated or standing still in attendance but are comfortably crossing through the space. In imagining the interior of the Hall prior to the completion of the building, the artist is preoccupied with the ordered movement of spectators as integral to the architecture. In a similar way, the accompanying report is less concerned with acoustic or scenic features than with a quantifiable capacity to traffic large moving crowds while adapting to a range of functions:

The centre of the building is occupied by a spacious arena, 102 ft. by 68 ft., capable of accommodating 1000 people … The southern extremity of the hall is occupied by a spacious orchestra, with places for 1000 performers, the seats of which are so arranged that the lower rows for instrumentalists take up the same lines as the amphitheatre seats. Thus, when the hall is not in use for musical purposes, by removing the inclosing rails of the orchestra a perfect amphitheatrical form is obtained … Each box will have a retiring-room at the back, which will communicate with a corridor running round the building at the level of each tier … The whole of these passages and approaches combine every facility for the ready ingress and egress of crowds of visitors to all parts of the building.Footnote 36

Figure 2. Imagined interior of the Royal Albert Hall prior to construction, Illustrated London News, 25 May 1867. Courtesy of the Mary Evans Picture Library.

Here the ideal of the classical amphitheatre – with its elliptical shape and open-air atmosphere – merges with the rhetoric of circulation and hygiene central to urban improvement.Footnote 37 Indeed, if the Illustrated London News was especially taken with the efficiency of the building’s symmetrical lines, curved corridors, passageways and multiple staircases, its emphasis on the ‘ingress and egress of crowds’ found a parallel in accounts of the building’s innovative ventilation and heating system. In the architectural journal The Builder, the engineer Gilbert Redgrave described an intricate network of steam-powered boilers, coiled pipes, fans, inlets and exits, all carefully designed to regulate the circulation of fresh air and facilitate a sanitised environment.Footnote 38

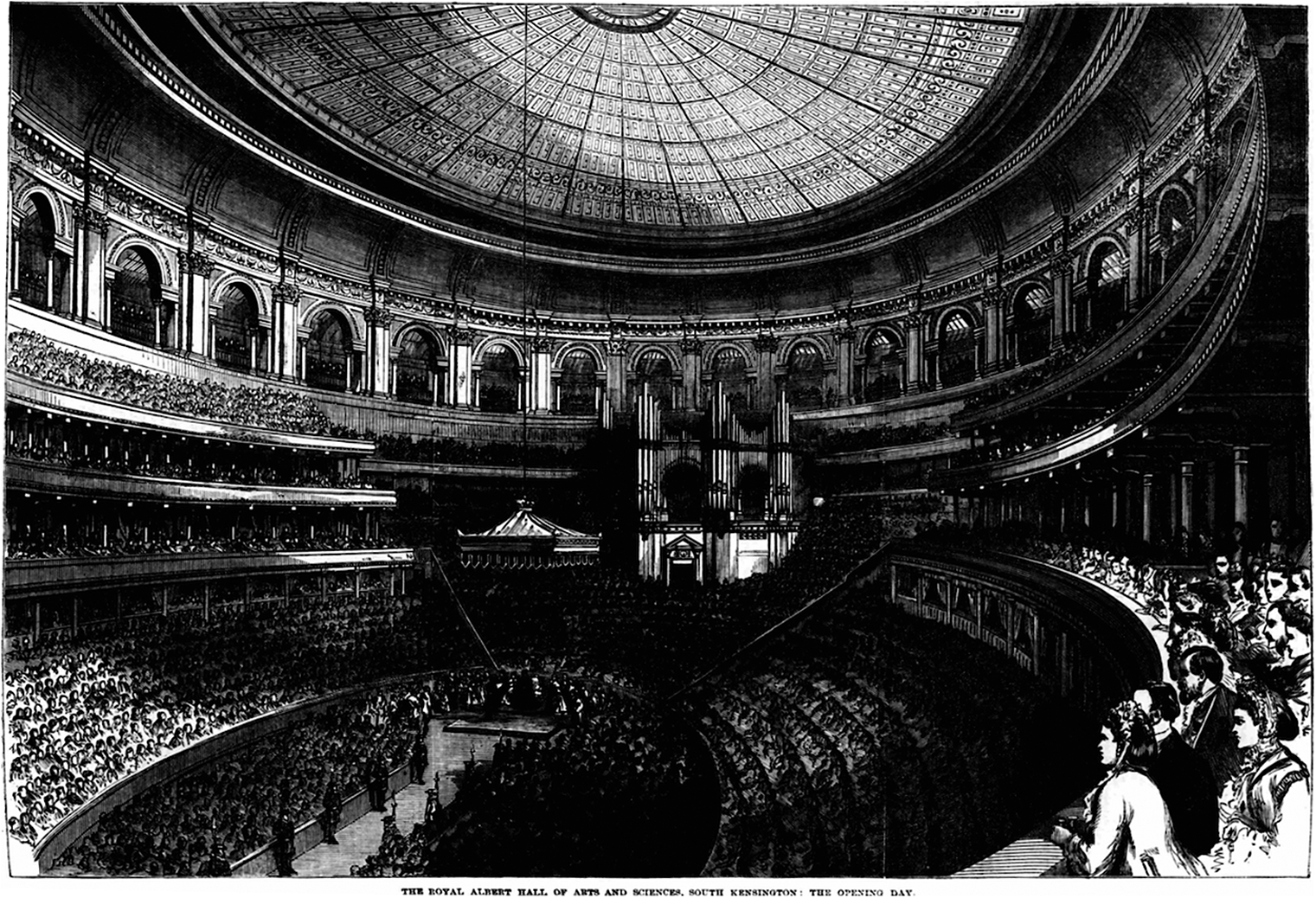

The opening ceremony on 29 March 1871 was an occasion of state pageantry intended to evoke memories of the Great Exhibition twenty years earlier, while replicating the scale of massed orchestral concerts and choral festivals that had since come to define the musical afterlife of the Crystal Palace at Sydenham. Following a formal address by the Prince of Wales and prayers led by the Bishop of London, Michael Costa conducted an orchestra of 500 instrumentalists and 1,200 singers from the Sacred Harmonic Society, the Handel Festival and Crystal Palace chorus (Figure 3). Yet the speeches and singing were notoriously marred by echo. If Henry Cole and his committee had intended to construct a perfectly controlled civic space for seeing on a grand scale, responses in the London press were dominated by debates over the building’s problematic acoustics. While some reports were more favourable than others, there was general agreement that the Hall would be suitable primarily for large-scale orchestral and choral forces, and that its future musical success would depend at the very least on judicious programming.Footnote 39

Figure 3. Opening of the Royal Albert Hall on 29 March 1871, Illustrated Times, 8 April 1871. The image shows the glazed roof, which was in reality shielded by the calico velarium designed to prevent glare and dampen resonance. Newspaper image © The British Library Board. All rights reserved. With thanks to The British Newspaper Archive (www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk).

Even before the official opening, concerns had emerged about problems of projection in such an enormous auditorium; the acclaimed actor and theatre manager Dion Boucicault, for instance, argued in a letter to the Pall Mall Gazette that the vast proportions of the Hall would not accommodate the human voice and would be unfit even for a large chorus.Footnote 40 As the building neared completion, Queen Victoria visited in December 1870 and listened to sound tests from various points in the Hall with the wooden scaffolding still in place.Footnote 41 By the time of opening, the scaffolding was removed and interior furnishings were installed, including a large calico velarium designed to prevent glare from the glass roof and reduce excessive resonance. Yet adjustments to the interior did not prevent damning criticism of the design from within the architectural community: Building News concluded that ‘in acoustic qualities the hall is undoubtedly deficient’ and that ‘compositions which depend for their effect on elaborate detail had better be left unattempted’.Footnote 42 Even the building’s chief engineer, Henry Scott, was prompted to justify his errors in a letter to The Times, remarking that ‘the principles of acoustics, like the principles of strategy and tactics, are in themselves not difficult to understand, but their application in practice is quite another affair’.Footnote 43

Acoustic failure and the concert hall of the future

There is clearly an irony embedded here: the acoustic deficiencies of a building explicitly intended to symbolise progress in science and technology emerged at a time when modes of knowing and quantifying sound, as well as attitudes to musical listening, were becoming increasingly important to the Victorians. While the origins of acoustics as a field of specialist mathematical enquiry can be traced to the publication of Lord Rayleigh’s magisterial academic treatise The Theory of Sound (1877), a longer tradition of popular science writing on experimental acoustics in Britain dates back to publications such as John Herschel’s article on ‘Sound’ for the Encyclopedia Metropolitana (1830) and Mary Somerville’s On the Connexion of the Physical Sciences (1834).Footnote 44 In 1867, the same year as the release of the architectural plans for the Albert Hall, John Tyndall delivered his series of lectures on sound at the Royal Institution in Mayfair, gaining recognition as an authority in experimental acoustics grounded in Helmholtz’s physiological approach to hearing.Footnote 45

If the drive to visualise and decipher the properties of sound acquired a tangible presence within London’s scientific culture, efforts to control sound as an audible experience within particular spaces and environments proved altogether more elusive.Footnote 46 The well-documented sensory overload experienced by visitors to the Great Exhibition at Crystal Palace in 1851 is a case in point. Here musical performers competed with the din of mechanisation and crowds, while sounds made by the mass orchestral forces on show for the opening ceremony disappeared into the vast crystalline transept.Footnote 47 Even after relocation to Syndenham and the establishment of more formal music making at the Crystal Palace, the problem of acoustics persisted. The famous mass Handel Festivals, often seen as quintessential symbols of Victorian nationalism and middle-class cultivation, were also a testing ground for pragmatic experiments in sound projection, raising concerns about the need for a more systematic convergence of science and performance.Footnote 48 In a piece aptly headed ‘The Power of Sound’, published soon after the Handel Commemoration Festival of 1859, an anonymous writer to the Musical Times lamented the inconsistent acoustic effects of such a large orchestra. That the combined forces of 2,765 voices and 456 instruments should have failed to match up to the grandeur of the Crystal Palace in volume and precision was not just a matter for musical judgment, but an impetus for scientific progress: ‘there have been very few buildings ever constructed that appear to fulfil all the requisites for the proper conveyance of sound, and it would be very desirable if the knowledge of acoustics were better understood’.Footnote 49

While Victorian commentators acknowledged the limitations of architectural acoustics as an emerging field, they also attempted to address the relationship between listening and building design based on empirical observation and experiment. As the historian of science Graeme Gooday has argued, nineteenth-century approaches to architectural acoustics emphasised the value of instinctive or experiential approaches, even while they lacked the exacting science of successive generations.Footnote 50 In 1839 the engineer John Scott Russell had proposed a theory of ‘isoacoustics’, a democratic principle of angles for seating design allowing unobstructed hearing for all listeners in a large building.Footnote 51 The architect Thomas Roger Smith later incorporated the principle into his Rudimentary Treatise on the Acoustics of Public Buildings (1861), a text that Gooday interprets as both a significant precursor to twentieth-century pioneers such as Wallace Sabine, and as an alternative approach to acoustics based on personal experience rather than abstract formulas.Footnote 52 Smith grounded his recommendations in an aspiration to curb all obstructions to sound, using the language of efficiency in a manner in keeping with Redgrave’s account of circulating air in the Albert Hall. ‘An obstruction to the free passage of sound’, he declared, ‘is presented by every adverse current of air and every variation in the quality of the atmosphere or its temperature, by every sudden contraction of the space through which sound has to travel, and by some, if not all sudden enlargements of space.’Footnote 53 Defending the acoustic design of the Hall to the Royal Institute of British Architects in January 1872, Scott acknowledged Smith as an important interlocutor, particularly in the decision to fit resonant wooden soundboards modelled on the success of the Surrey Music Hall and the Free Trade Hall in Manchester. After treating the calico velarium to prevent sound escaping into the domed roof, however, both admitted that echoes were still detectable in some parts of the building, while Smith later concluded that the acoustic defects were an inevitable outcome of the cove between the domed roof and the elliptical walls.Footnote 54

In the aftermath of the Albert Hall’s completion, one contributor to the RIBA went beyond the analysis of defects in the building’s acoustics to offer some broader insights into the relationship between instrumental music and architecture in modern times. Henry Heathcote Statham responded to the acoustics of the Hall by pointing to a disparity between aesthetic form and practical purpose in buildings for music, stressing a conflict between the architectural vogue for classical revivalism and a sense of the new in contemporary musical life:

A building for musical performances on a large scale is one of those things for which there really is no precedent previous to our own architectural dispensation. Music is pre-eminently the modern art, the only form of high art which has, practically, had its rise during the era of modern life, and the grandest results of which have been realized almost within our generation, in those choral and orchestral performances on a large scale, which are becoming year by year more frequent and more frequented among us.Footnote 55

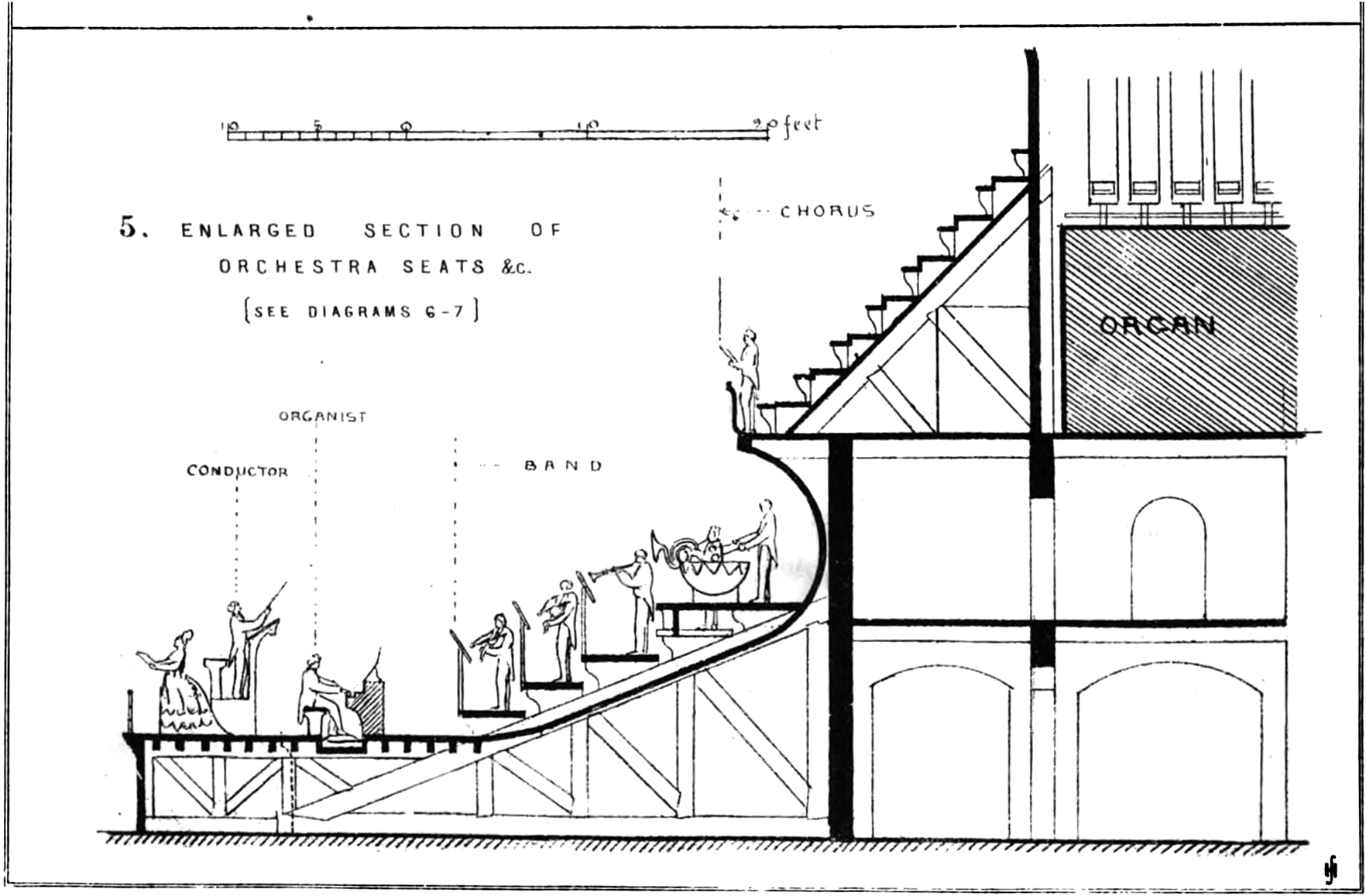

Statham went on to distinguish between the ear of the acoustician and the ear of the musician, with only the latter capable of discerning expressive intricacies of harmony and phrasing in the moment.Footnote 56 As he saw it, the building’s compromised acoustics were ‘the inevitable result of applying to a building for music an arrangement originally intended for a spectacle’.Footnote 57 Particularly striking is that Statham proceeded to offer recommendations for an imagined concert hall of the future, one that would meet the demands of instrumental performance and attentive listening in the modern age (Figure 4). This ideal concert hall would be rectangular with a flat roof; it would allow a consistent listening experience for each audience member; it would follow tried and tested guidance on proper materials for resonance, avoiding glass, iron, canvas and cloth in favour of timber and brick; and it would provide a spacious, semi-enclosed platform for the orchestra beneath the choir and organ. In visualising an improved placement of musicians, Statham suggested enclosing the orchestra within ‘a kind of wooden shell or sound-board bending round them in the rear, and coming under their feet to the front’. The integrated soundboard would extend as a covering over the louder brass and percussion sections at the back, allowing the sound to be reflected efficiently and cleanly into the room while veiling excess noise for the singers and providing a ‘consentaneous union of instruments’.Footnote 58

Figure 4. Henry Heathcote Statham, part of a sketch of a semi-enclosed orchestra platform for an imagined concert hall, in ‘Architecture Practically Considered in Reference to Music’, Transactions of the Royal Institute of British Architects (20 January 1873), 81–99 (85). Courtesy of the RIBA Library.

Statham’s close attention to the placement of musicians for the purposes of acoustic control suggests on the surface a striking resemblance to Wagner’s proposals for controlling the projection and balance of instruments through encasing the orchestra within a wooden sounding board. Just as Wagner had envisaged a theatre made from locally sourced materials in opposition to industrial mass production, so Statham campaigned against the dominance of iron construction in favour of a musical building that would ‘combine utility and character’ through the use of resonant oak. Taking as his model the provisional structure erected for the first commemorative Beethoven festival at Bonn in 1845, Statham in 1873 imagined an organic building specifically for hearing instrumental music, a model auditorium that would be stripped of unnecessary ornament to expose its entire construction – including supports and framing – as integral to acoustic effect.Footnote 59 While this insistence on the regulation of orchestral sound certainly points to Wagnerian concerns about acoustic control; however, Statham would also make clear his discrepancies with Wagner from both an architectural and a musical perspective.

In his capacity as a music critic, Statham penned a lengthy critique of Wagner’s stance on opera reform. Published in January 1876, in anticipation of the upcoming Bayreuth festival, Statham’s essay on ‘Wagner and the modern theory of music’ reflects his engagement with the scores of Tristan and the Ring, as well as his critical reading of Wagner’s aesthetics.Footnote 60 His objections to Wagner stem in large part from his implicit preference for the value of instrumental music over opera, which Statham associated with elite entertainment and privilege. Approaching Wagner through the common binary between ‘art’ music and theatrical ‘entertainment’, he turns the composer’s own critique of opera against him, criticising his reiteration of orchestral ‘tricks’ in Das Rheingold and his use of instrumental music to illustrate ‘glorified pantomimes’.Footnote 61 Indeed, Statham opposed Wagnerian music drama in much the same terms as he objected to the acoustics of the Albert Hall. He argued that Wagner taints instrumental music through a union with spectacle, suggesting that the composer’s aesthetics of music drama amount to a ‘preference for impulse and sentiment before form, colour before outline’.Footnote 62 Above all, he objected to Wagner’s appropriation of Beethoven, and alluded to a ‘clique of critics’ intent on promoting the Gesamtkunstwerk as the logical endpoint in the modern history of symphonic music.Footnote 63

Disseminating music drama: from theatre to concert hall

In this last broadside, Statham was responding to prominent Anglo-German supporters of Wagner in the English periodical press, who sought to reconcile the promotion of his operas with the moral and aesthetic value attached to instrumental music. Shortly following the publication of Wagner’s Beethoven (1870), the musical critic Francis Hueffer had penned an extended defence of the composer’s Schopenhauerian aesthetics of music drama for The Fortnightly Review. Footnote 64 Whereas Hueffer interpreted Wagner primarily through his allegiance to Schopenhauer, Edward Dannreuther offered more in-depth readings of Wagner’s music philosophy, readings that were inspired in part by Friedrich Nietzsche’s recent eulogising of music drama as a revival of the Dionysian musical spirit of tragedy.Footnote 65 In a series of articles for the specialist journal The Monthly Musical Record, Dannreuther followed late Wagner and early Nietzsche in emphasising the redemptive power of German music after Beethoven to bypass the rational intellect and speak directly to the emotions, thereby transforming the conditions of art in contemporary life.Footnote 66 Employing a dual concept of music as both sounding reality and as a metaphorical undercurrent to poetry and myth, he regarded all aspects of Wagner’s approach to drama as ‘imbued with the spirit of music’.Footnote 67 When Dannreuther was later invited to publish further articles for Macmillan’s Magazine (edited at that time by George Grove), he lauded Wagner’s music for its affective immediacy, its ability to express and evoke emotion ‘with a minimum of logical mediation’.Footnote 68 Extending the composer’s own aspirations for instinctive musical communication, and anticipating an argument that would later become central to Bernard Shaw’s promotion of the Ring, Dannreuther implied that the intricate and detailed web of musical themes running across the entire drama would speak as much to the ‘layman’ as to the musical ‘connoisseur’.Footnote 69

Dannreuther’s writings – with their insistence on the expressive immediacy of Wagner’s melodies – coincided (ironically) with the emergence of explanatory programmes designed to mediate performances of instrumental music for listeners in both Britain and Germany. As Christian Thorau and Christina Bashford have shown, the advent of the annotated programme or listening guide was initially a distinguishing feature of concert life in Britain, beginning with John Ella’s chamber music series and Grove’s Saturday concerts at the Crystal Palace.Footnote 70 The tradition of the synoptic programme book was later continued and expanded with the publication of Hans von Wolzogen’s Thematischer Leitfaden durch die Musik zu Richard Wagners Festspiel ‘Der Ring des Nibelungen’ (Thematic guide through the music of Richard Wagner’s festival drama The Ring of the Nibelungen), a systematic commentary on the work published in advance of the Bayreuth festival and available for purchase during the event. Intended as a supplement for Wagnerian listeners, the leitmotivic guide functioned – in Thorau’s terms – as a touristic ‘marker’ for the performance of the Ring cycle: it served to guide listeners through an unfamiliar and challenging sound world and helped to assimilate the work into a bourgeois canon of classical works.Footnote 71

It is no coincidence, then, that Dannreuther sought to emphasise the democratic appeal of Wagner’s melodies for the ‘layman’ within the context of Grove’s Macmillan’s Magazine, which aimed at educating a broad readership and concert-going public beyond professional musicians. While Hueffer’s and Dannreuther’s extensive dissemination of German musical metaphysics was unusual for English periodical criticism at this time, they voiced underlying philosophies that clearly spoke to a growing fascination with musical meaning and appreciation. As Ruth Solie has shown through her analysis of music’s wider recurrence in Macmillan’s during the Grove years, Dannreuther’s Wagnerian panegyric was consistent with a tendency for authors to treat Austro-German instrumental music as the cultivated art of a progressive modern age.Footnote 72 But if these musical writers advanced philosophical discourses about the power of instrumental music within the colloquial format of the periodical press, their aesthetic values were also entangled with the built environment, and with practical considerations about music’s sounding presence.

The intersection of music criticism and concert reform was clearly exemplified in the anti-Wagnerism of the musician–architect Statham, whose thoughts on the virtues of reverent listening to the inner unfolding of musical form coincided with his campaign for a self-conscious ‘modern architecture’ based on functional principles grounded in acoustic science. Even for Hueffer and Dannreuther, though, the production of philosophical and ideological tracts about the transformative musical spirit of Wagnerian opera coincided with practical initiatives in arts fundraising, concert programming and conducting. Indeed, the concert dissemination of Wagner’s music dramas in London owed much to the activities of these émigré musicians and intellectuals, who went on to establish the first London Wagner Society.Footnote 73 Between February 1873 and May 1874, Dannreuther directed nine fundraising concerts at the Hanover Square Rooms and St James’s Hall with programmes consisting of music by Wagner, Liszt and Berlioz. To a certain extent, these programmes continued an established practice of performing orchestral excerpts from Wagner’s ‘Romantic’ operas, a practice associated particularly with August Manns’ popular Saturday Concerts at the Crystal Palace. But the idea of dedicating entire concerts to the music of living composers was nonetheless a novelty within London concert life, reflecting the wider specialisation of classical music programmes and the ‘new seriousness’ that accompanied the gradual move away from miscellaneous concert programming.Footnote 74 By presenting Wagnerian excerpts self-consciously as ‘new music’ in a symphonic tradition, Dannreuther’s concerts were explicitly designed to distance Wagner from Italian opera and erase any negative associations with an older tradition of programming operatic excerpts. In this respect, he took inspiration from a practice initiated by Wagner himself, who (with the assistance of a team of copyists) first began arranging orchestral excerpts from the Ring for a series of seminal concerts in Vienna in 1862–3.Footnote 75

The Albert Hall concerts of 1877 thus built on an established tradition of promotional Wagner concerts, which were becoming a fixture of urban performance culture by the 1870s. Capitalising on the high-profile media attention that surrounded the Bayreuth Festival the previous year, the concerts were marketed as an alternative Wagner Festival with programmes dedicated exclusively to the performance of scenes and excerpts from Rienzi to Götterdämmerung. If pre-Bayreuth concert performances of the Ring provided a ‘preview of coming attractions’, the Albert Hall series commemorated the premiere by attempting a fuller musical reproduction.Footnote 76 Indeed, the London Wagner Festival marked a new departure in so far as it advertised the programming of lengthy scenes and complete acts as a novel feature of the series. Each concert was to comprise a first half showcasing segments from Wagner’s operas and occasional pieces up to Die Meistersinger, followed by a second half featuring large chunks from the Ring cycle.Footnote 77 Wagner directed the first half of each programme, while Hans Richter stepped in to conduct the performances of the Ring, leaving the composer to listen conspicuously from the front of the orchestra.

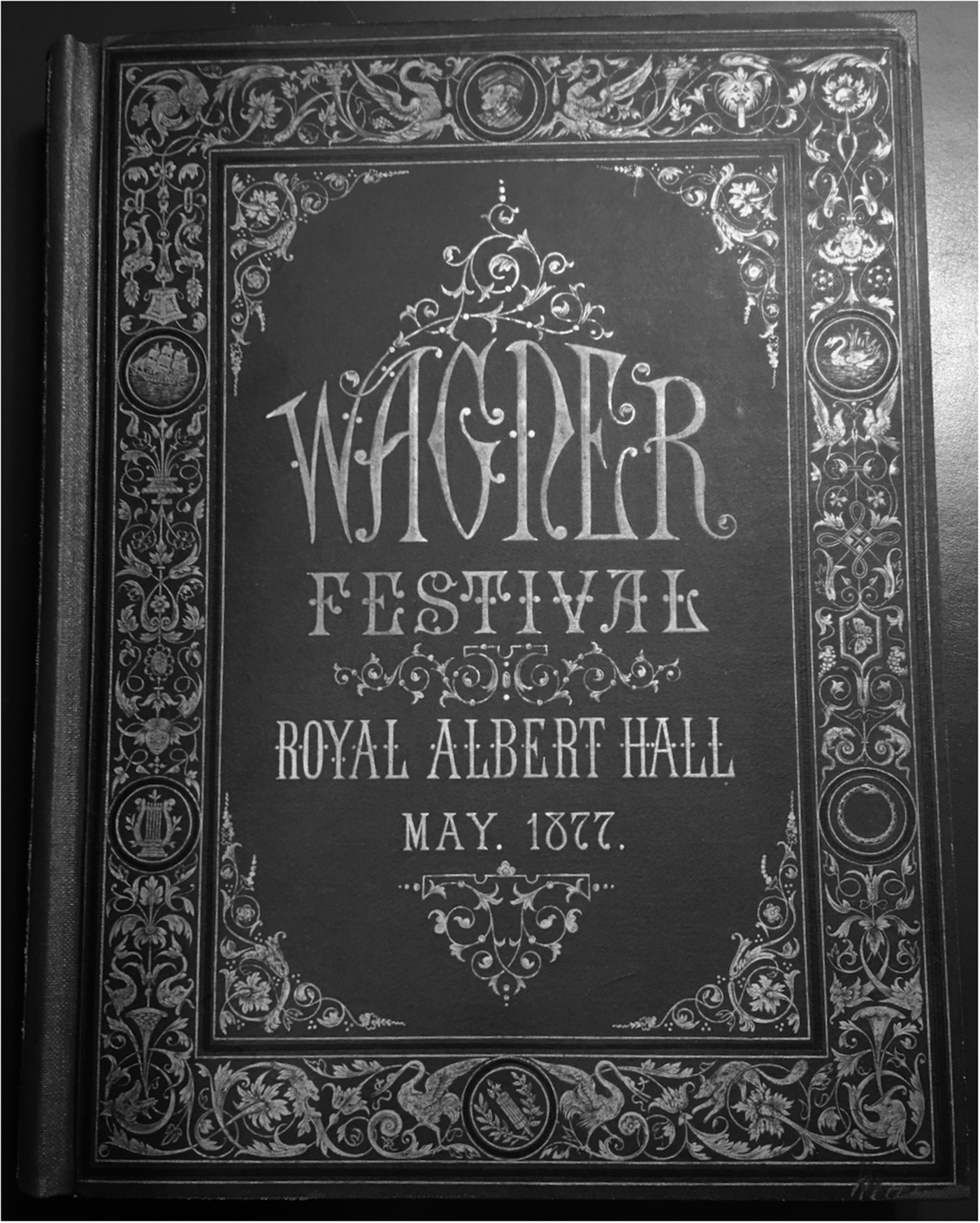

The aesthetic implications of Wagner’s programming decisions were by no means lost on his supporters, who extolled in advance the opportunity for thousands of concert-goers to experience large parts of Tristan and the Ring for the first time. Writing in The Academy prior to Wagner’s arrival, the critic Ebenezer Prout emphasised the uniqueness of the six anticipated programmes, which he described as ‘one long crescendo’, giving ‘a complete epitome of Wagner’s works’.Footnote 78 The impression of an integrated œuvre and unified compositional method was further emphasised within the lavish bound programme book that accompanied the series (Figure 5a). Owing to the absence of visual scenery and the omission of sections of the drama, the physical programme took on added significance as a tool for the uninitiated listener. In this respect, it contributed in a distinctive way to the aforementioned ‘leitmotivic reception’ of Wagner’s works that did much to domesticate his operas as products for bourgeois listeners.Footnote 79 As an early imitation of Wolzogen’s Thematic Guide, the London programme gave an abridged catalogue of selected ‘leading themes’, interspersed with plot synopses and relevant extracts from the libretti. In addition, it displayed principal motifs from the Ring alongside musical examples from Wagner’s earlier operas (Figure 5b). By presenting musical motifs in this way, the programme was designed to orient the listener within the sonic architecture of Wagner’s operas, providing an aide for appreciating his musical dramas at the level of discrete melodic units. It also provided concert-goers with a luxury souvenir, one that complemented other official merchandise advertised by Schott, including Karl Klindworth’s piano-vocal scores of the Ring cycle. Blending the format of the taxonomic listening guide with that of the exhibition catalogue, the hefty programme book even participated more widely in the burgeoning culture of Victorian advertising by including a supplementary ‘Wagner Festival Advertiser’, illustrating the latest desirable commodities and branded goods.Footnote 80

Figure 5a. Programme for the London Wagner Festival, Royal Albert Hall, 1877. RAHE/1/1877/2. Courtesy of the Royal Albert Hall Archive.

Figure 5b. Page from the London Wagner Festival programme (1877), showing the incorporation of notated musical examples to guide the listener. RAHE/1/1877/2. Courtesy of the Royal Albert Hall Archive.

For all its ambitious programming, the reality of the London Wagner Festival ultimately fell short of expectation, not least because of the unsustainable demands placed upon the principal singers. By the fourth concert, Unger and Hill suffered severe hoarseness, prompting a succession of last-minute changes to the final three concerts, including the omission of much of the planned second act of Tristan and all of the proposed scenes from Siegfried. Meanwhile, reports of the acoustic idiosyncrasies of the capacious arena inevitably resurfaced as the singers sought to project against the massed orchestral forces. Prout expressed anxieties about the inconsistencies of the Hall’s acoustics for comprehending the more delicate orchestral effects,Footnote 81 while a critic for The Musical Standard confirmed that, from their position near the orchestra, the first performance was ‘very much interfered with by echo, which, although not directly audible, made itself felt by confusing everything and rendering many passages mere noise’.Footnote 82 Similarly, Cosima Wagner reported that even from her seat in the grand tier – where she was joined by George Eliot and George Henry Lewes – she was ‘horrified by the sound’, experiencing a ‘double echo’ that drowned out the singers.Footnote 83

In the end, the Albert Hall series did much to disseminate repeatable highlights from the Ring, with the ‘Ride of the Valkyries’ proving a predictable hit.Footnote 84 Even Wagner’s sympathisers admitted that the anticipation of musical completeness had descended into the presentation of miscellaneous excerpts.Footnote 85 Still, this did not prevent his more enthusiastic supporters from advocating the ‘purely musical’ value of these selections outside the theatre. In a series of reviews for The Examiner, Hueffer would go furthest in justifying concert performances of Wagner as part of a broader conviction in music drama as an essentially acoustic phenomenon. As he saw it, the success of Wagner’s operas in the concert hall helped to disprove a belief that his musical dramas relied on extraneous theatrical machinery and visual effects. Instead, the Albert Hall concerts showed how the immaterial essence of the drama could be conveyed to a varied listening public as something intrinsic to the music alone:

Here was no darkened theatre, no invisible orchestra, no elaborate machinery – merely a few ladies and gentlemen, in ordinary evening dress, and in ordinary concert-room surroundings. And the rushing and gushing of the mighty river, enlivened by the merry gambols of the water-maidens, was placed before the imagination with a distinctness, perhaps all the more vivid as the ear alone conveyed the charm to the mind.Footnote 86

By portraying an opposition between the ‘elaborate machinery’ of the theatre and the ordinary surroundings of the concert hall, Hueffer upheld a Romantic belief in the power of Wagner’s melodies to bypass the other senses and convey meaning to the ear and mind directly.

From the other side of the debate, prominent anti-Wagnerians were quick to parody the reversion to operatic excerpts in concert form as symptomatic of the fallacy of the total work of art. Following the musician–architect Statham, Joseph Bennett (music critic for The Daily Telegraph) satirised Wagner’s dismemberment of the Ring as a concession to the market, one that went against the serious aspirations of the modern symphonic concert, and undermined the composer’s own supposed conviction in the unbreakable wholeness of the integrated work of art.Footnote 87 In stressing Wagner’s mass commercial appeal, Statham and Bennett anticipated the tendency of later philosophical critics to target Wagner’s apparent exploitation of the orchestra as a technology for integrating theatrical effects. Theodor Adorno would extend established nineteenth-century complaints to portray Wagner’s techniques as marking the demise of ‘genuine’ musical development (which he associated with Viennese classicism) in favour of musical tableaux that would sustain the attention of great numbers of inexpert listeners at a distance. Adorno believed that the commodity character of Wagner’s works was rooted above all in the ‘primacy of harmonic and instrumental sound in his music’, lending his operas a quality of magical artifice reminiscent of the phantasmagoria.Footnote 88 Adorno’s critique of Wagnerian phantasmagoria is often equated with the architectural conditions of the Bayreuth theatre, and with the innovation of its ‘invisible orchestra’ in particular. Yet the ‘great phantasmagorias’ that Adorno identified – the Venusberg music from Tannhäuser, the Magic Fire music from Die Walküre and the closing scene from Götterdämmerung – were also chief among the popular highlights that Wagner extracted for presentation in concert form.Footnote 89 The performance of operatic scenes and orchestral highlights in the heart of London’s burgeoning museum district brought Wagner’s music directly into the orbit of modern consumption practices in such a way as to literalise the analogy between musical technique and commodity fetishism. If the Festspielhaus enacted a separation between hearing and seeing in the service of musical transcendence, the London Wagner Festival rematerialised the orchestral machine as an emblem of industrial progress within the arena of Victorian spectacle.

Coda

By the time Wagner left London and returned to Bayreuth in June 1877, his conception of the Ring in performance had come a long way from the idea of a radically transitory event as sketched in his correspondence of the 1850s. The failure of the Albert Hall concerts to make a profit and help resolve the deficit arising from the production costs of the Bayreuth Festival only added to his sense of disappointment that the much-anticipated premiere had fallen short of his ideal. As is well known, the prospect of a repeat performance of the Ring in Bayreuth proved unviable during Wagner’s lifetime and he soon agreed to transfer rights to the impresario Angelo Neumann, a devoted Wagnerian whose sold-out productions of the Ring in Leipzig (1878) and Berlin (1881) led to the establishment of the travelling ‘Richard Wagner Theater’ in 1882. It was in London that Neumann launched his international touring Ring cycle, bringing together a mobile orchestra led by the conductor Anton Seidl, a chorus and cast of Wagnerian singers, and a technical team dedicated to installing the disassembled Bayreuth décor and machinery as a model production in theatres across Europe. Early in 1882, he and his team of technicians transferred to Her Majesty’s Theatre the ‘appurtenances’ which had ‘lain for six years in the storehouses of the Bayreuth theatre’, while Seidl – as Wagner’s approved conductor – drilled the orchestra in preparation for the first of four instalments of the complete cycle.Footnote 90 On the back of the London premiere in May, the company spent the next year crossing continental Europe on a chartered train, mounting over twenty productions of the Ring, as well as promotional concerts, in theatres and concert venues throughout Europe. As Gundula Kreuzer has suggested in her post-Kittlerian reading of Wagner’s staging of the Ring and its translocation beyond the Festspielhaus, Neumann’s operatic assemblage emphasised fidelity to Wagner’s musical and directorial intentions by using original materials and artifacts from the Festspielhaus, in addition to performers (Seidl in particular) as agents of the ‘faithful’ rendition. ‘If the Bayreuth Festspielhaus functioned as a stationary machine with recording and playback functions,’ she writes, ‘the touring production was its itinerant amplifier, designed to extend both reach and shelf life of Bayreuth’s inaugural staging.’Footnote 91

In comparison to the elaborate technological production of the Ring on stage, Wagner’s journey to London in 1877 has been overlooked as a desperate attempt to reap back profits by reverting to ordinary concertising. Yet for all its flaws, the London Wagner Festival continued an established practice of performing concert arrangements of the Ring and provided a precedent for Neumann’s fully staged touring production five years later. It is tempting in this respect to extend Kreuzer’s media interpretation of Neumann’s touring Wagner Theatre to include the earlier London initiative. Whereas Neumann presented his touring Ring as a trademark reproduction on stage, the London Wagner Festival marketed fidelity by engaging an approved cast of Wagnerian singers, players and conductors. In the absence of stage décor, the orchestra – which was led by Wilhelmj, disciplined under Dannreuther and conducted from memory by Richter – operated as a playback mechanism in full view of the audience and under the eye of the composer, his celebrity endorsement bestowing the ultimate seal of approval.

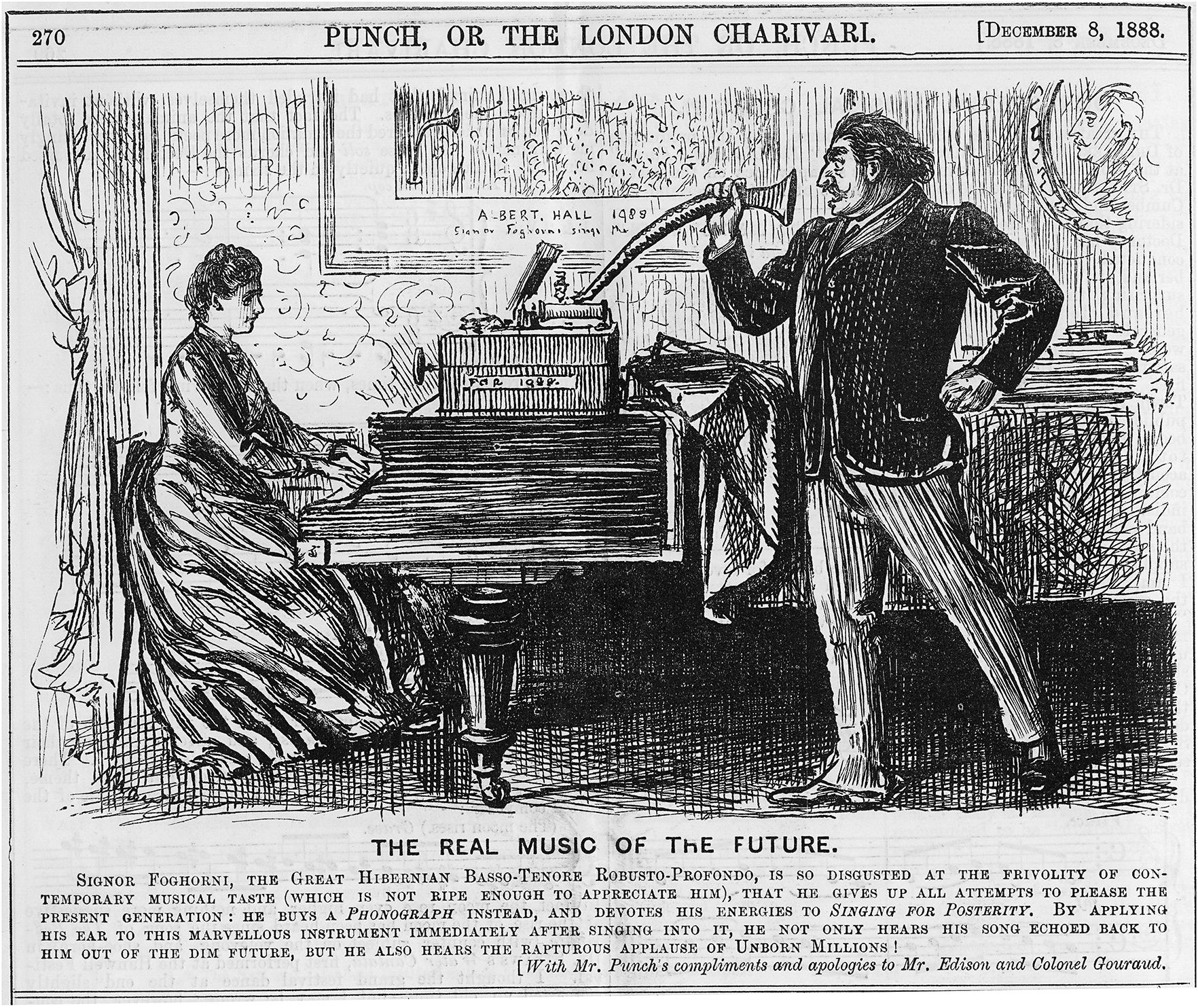

More than a decade after Wagner’s final visit to London, the association between Wagnerism, mass listening and sound technology was captured in a popular caricature for Punch by the prolific illustrator and chronicler of the Victorian middlebrow, George du Maurier (Figure 6). One of many visual parodies of Wagnerian aestheticism and ‘the music of the future’ to be found within the pages of the magazine, ‘The Real Music of the Future’ features an imaginary Wagnerian performer who is ‘so disgusted at the frivolity of contemporary musical taste’ that he ‘buys a phonograph instead, and devotes his energies to singing for posterity’.

Figure 6. George du Maurier, ‘The Real Music of the Future’, Punch, 8 December 1888, 270. Courtesy of Senate House Library, University of London.

Du Maurier’s musician is seen posing within a traditional Victorian drawing room turned home recording studio, wherein the phonograph appears domesticated as an instrumental extension of the piano (operated by the ubiquitous woman at the keyboard). In the background hangs a picture of the Royal Albert Hall, re-imagined as a futuristic shrine to mechanical playback and mass consumption. Next to it is a portrait of Colonel Gouraud, the American Civil War veteran who assumed responsibility for marketing Thomas Edison’s latest phonograph in Britain by recording illustrious voices and musical occasions, including the first known reproduction of a live concert: a mass performance of Handel’s Israel in Egypt performed at the Crystal Palace on 29 June 1888.Footnote 92 Coinciding with Edison’s re-launch and marketing of his new and improved phonograph the same year, du Maurier’s cartoon juxtaposes old and new modes of musical performance and reproduction to imagine the future potential of sound archiving and long-range communication as a feature of everyday life. It also combines Victorian fantasies of a technological future with anxieties about Wagnerian modernity, hinting at a parallel between the archival capacities of the phonograph, and the preservationist impulse underpinning the production of high art.Footnote 93

Victorian spectacles of mass listening (of which the London Wagner Festival of 1877 was a prime example) may seem divorced from opera’s entwinement with media history, its multisensory wholeness as a ‘massive techno-cultural complex’.Footnote 94 However, this separation – between the audiovisual mechanisms of opera in the theatre and the ‘purely musical’ arena of the concert hall – was also one that nineteenth-century critics and concert reformers actively sought to foster. The Albert Hall’s acoustic limitations and miscellaneous purpose contrast sharply with the much-lauded innovations of the Bayreuth Festspielhaus; yet this heavy monument, with its roots in the Great Exhibition and imperial visions of European progress in science and industry, also stands as an enduring reminder of the technological conditions underpinning the loftiest musical ideals.

Acknowledgements

The completion of this article was made possible thanks to support from the ERC-funded ‘Sound and Materialism in the 19th Century’ project, principal investigator David Trippett at the University of Cambridge. I am grateful for the assistance of Elizabeth Harper and Suzanne Keyte at the Royal Albert Hall archives and Kristina Unger at the National Archives of the Richard Wagner Foundation, Bayreuth. Special thanks to Roger Parker, Laura Vasilyeva and Francesca Vella for comments on earlier drafts, and two anonymous peer reviewers for their constructive feedback.