Impact statement

Global plastic pollution has been shown to have nefarious effects on biodiversity, the environment and human health. Waste pickers play a key role in mitigating global plastic pollution by recovering, classifying and processing an array of plastics that would otherwise end up in the environment. Simultaneously, they suffer from the adverse effects of plastic pollution in their working lives and communities and are potentially vulnerable to the control measures being discussed as part of negotiations to develop an international legally binding instrument to end plastic pollution. This article documents and analyses the ways that waste pickers have succeeded in becoming a “human face” of the global plastics treaty and the strategies they have employed to influence and gain prominence in treaty proceedings, events and draft text. The authors expect that the analysis will be helpful to environmental and social justice groups seeking to influence global environmental governance (GEG), such as waste pickers and their organisations. It is among the first pieces of research exploring the role of waste pickers in the global policy arena, complementing research on waste picker advocacy at national and regional scales and that on Indigenous Peoples’ role in GEG.

Introduction

Global waste generation has doubled over the past two decades, reaching an estimated 353 million tonnes (Mt) in 2019 (OECD, 2022). Seventy percent of this waste ends up in landfills and uncontrolled dumpsites, while 117 Mt has leaked into aquatic, marine and riverine environments (ibid). The transboundary and unequally distributed impacts of plastic pollution (Lau et al., Reference Lau, Shiran, Bailey, Cook, Stutchey, Koskella, Velis, Godfrey, Boucher, Murphy, Thompson, Janokwska, Castillo, Pilditch, Dixon, Koerselman, Kosior, Favoino, Gutberlet, Baulch, Atreya, Fischer, He, Petit, Sumaila, Neil, Berhofen, Lawrence and Palardy2020; Bennett et al., Reference Bennett, Alava, Ferguson, Blythe, Morgera, Boyd and Côte2022) have been shown to adversely affect socio-economically disadvantaged and/or politically marginalised individuals and communities (Orellana, Reference Orellana2021; Owens and Conlon, Reference Owens and Conlon2021; Karasik et al., Reference Karasik, Lauer, Baker, Lisi, Somarelli, Eward, Fürst and Dunphy-Daly2023). Environmental injustices occur from upstream to downstream in the lifecycle of plastics. Communities and individuals face displacement and/or exposure from extractive petrochemical industries (UNEP, 2021; Terrell and St Julien, Reference Terrell and St Julien2022), mismanaged plastic waste and pollution affect coastal communities dependent on aquatic resources (English et al., Reference English, Holmes and Wagner2019; Fuller et al., Reference Fuller, Ngata, Borelle and Farrelly2022) and mismanaged waste impacts waste workers and communities living in and/or working in near proximity to areas where waste is dumped and/or processed (Human Rights Watch, 2022; Cook et al., Reference Cook, Cano and Velis2024). The systemic changes required to address the root causes of plastic pollution across scales are likely to impact some communities, industries and livelihoods more than others (Mekaoui et al., Reference Mekaoui2021; Nagarajan, Reference Nagarajan2022; Nøklebye et al., Reference Nøklebye2023). Enabling a just transition towards ending plastic pollution is thus key to protecting the rights of individuals, workers and communities who continue to bear the inequitably distributed impacts of plastic pollution and corresponding control measures (Stoett, Reference Stoett2022; ILO, 2023).

The just transition concept emerged from labour and environmental justice movements in the late 1960s. Since then, it has emerged to encompass impacts on individuals, communities, ecosystems and the climate, including for future generations, uniting the multiple dimensions of justice (distributional, procedural and restorative) (McCauley and Heffron, Reference McCauley and Heffron2019). It has been linked to green transitions away from coal and other environmentally damaging fossil fuel energy sources (Morena et al., Reference Morena, Krause and Stevis2019; Stevis and Felli, Reference Stevis and Felli2020) and was placed on the global environmental governance (GEG) agenda through the Copenhagen Summit (COP15) and the Paris Agreement (COP21) (Schroeder, Reference Schroeder2020), thus effectively straddling policy and scholarship on climate, energy and environmental justice. More recently, the concept has been brought into discussions around safeguarding affected communities and workers in the ongoing negotiations towards an international legally binding instrument to end plastic pollution, including the marine environment (henceforth, plastics treaty) (Dauvergne, Reference Dauvergne2023). In the negotiations, just transition has gone from being understood primarily as a workers’ rights issue (loss of jobs), towards recognising the broader implications for people and communities of the transition towards ending plastic pollution (including direct and indirect impacts of pollution and control measures) (Annex 1), even if the multiple dimensions of justice are arguably not currently reflected in the negotiations in the room and in the draft treaty texts. Here, a just transition has been understood as “ensuring that measures taken to end plastic pollution are fair, equitable and inclusive for all stakeholders across the plastic lifespan by safeguarding livelihoods and communities impacted by plastic pollution and corresponding control measures” (O’Hare et al., Reference O’Hare, Nøklebye, Stoett and Korsten2023). Such definitions are admittedly broad, and the popularity of the concept within plastic pollution governance is also partly based on its ambiguity. Different meanings can be grasped by different actors, ranging from a just transition away from plastic production altogether, to a transition away from single-use applications. One aspect of a nascent procedural justice that can already be identified, however, is the inclusion and recognition given to waste pickers as a key stakeholder that is both vulnerable to and helps to combat plastic pollution (GRID-Arendal, 2022; UN-Habitat and NIVA, 2022; Gutberlet, Reference Gutberlet2023).

Recent scholarship has placed waste pickers at the centre of achieving social and environmental outcomes within a circular plastics economy (Gutberlet and Carenzo, Reference Gutberlet and Carenzo2020; Barford and Ahmad, Reference Barford and Ahmad2021; Hartmann et al., Reference Hartmann, Hegel and Boampong2022; Velis et al., Reference Velis, Hardesty, Cottom and Wilcox2022). It is estimated that waste pickers collect 58% of all post-consumer plastic waste recovered for recycling worldwide (Lau et al., Reference Lau, Shiran, Bailey, Cook, Stutchey, Koskella, Velis, Godfrey, Boucher, Murphy, Thompson, Janokwska, Castillo, Pilditch, Dixon, Koerselman, Kosior, Favoino, Gutberlet, Baulch, Atreya, Fischer, He, Petit, Sumaila, Neil, Berhofen, Lawrence and Palardy2020). Commonly, it is estimated that waste pickers constitute a significant workforce of 15–20 million people globally (see, e.g., ILO, 2018; Morais et al., Reference Morais, Corder, Golev, Lawson and Ali2022). However, by scaling up uncertain estimates to account for development patterns, it is plausible that 34 million people around the world could be involved in this type of work (UNCTAD, 2022; see Cook et al. (Reference Cook, Derks and Velis2023, Reference Cook, Cano and Velis2024) for a recent discussion of different estimates).Footnote 1 Waste pickers play an indispensable role as service providers, contributing to urban sustainability and economies (Dias, Reference Dias2016), saving municipalities’ significant waste management costs (Kaza et al., Reference Kaza, Yao, Bhada-Tata and Van Woerden2018) and reducing climate emissions (WIEGO, 2021). Despite being the “backbone of collection and recycling systems in the world” (Chweya, in Laville, Reference Laville2023), waste pickers are particularly vulnerable to the adverse impacts of plastic pollution and associated chemicals; they often work in direct contact with contaminated waste materials under hazardous and sometimes exploitative working conditions, with limited access to social protection (WIEGO, 2018; Ferronato and Torretta, Reference Ferronato and Torretta2019; Harriss-White, Reference Harriss-White2020). Although the formalisation of waste work can improve waste picker conditions and income as part of a just transition (Pereira, Reference Pereira2010; Serrona et al., Reference Serrona, Yu, Aguinaldo and Florece2014), it can also threaten their jobs, diminish income and increase precarity (O’Hare, Reference O’Hare2020), particularly if waste pickers are not included in the design and implementation of the policies that affect them (Samson, Reference Samson2020; Parra and Vanek, Reference Parra and Vanek2023).

The scholarly attention paid to waste pickers’ role in the plastics treaty (Dauvergne, Reference Dauvergne2023; Velis et al., Reference Velis, Hardesty, Cottom and Wilcox2022 and Gutberlet, Reference Gutberlet2023) has been complemented by suggested measures aiming for a just transition (GRID-Arendal, 2022; UN-Habitat and NIVA, 2022; IAWP, 2023). Yet to date, there has been limited attention paid to the dynamics influencing the ways waste pickers have engaged and become visible in the plastics treaty process. As with biodiversity and conservation (Brosius and Campbell, Reference Brosius and Campbell2010: 247), ethnographic research has been conducted with waste pickers as they work in situ (e.g. Millar, Reference Millar2018; O’Hare, Reference O’Hare2022; Butt, Reference Butt2023) but much less as they intercede in spaces of negotiation. This article offers a preliminary analysis of how and why waste pickers have managed to achieve such prominence in plastics treaty negotiations. In setting out the tripartite schema of naming, performance and scale, we adapt Campbell et al. (Reference Campbell, Corson, Gray, MacDonald and Brosius2014)’s attention to translation, performance and scale as a key analytic for understanding GEG, recognising that the influence of civil society organisations (CSOs) can be evidenced in the written and oral statements made during the negotiation process and in draft as well as final text (Betsill and Corell, Reference Betsill and Corell2001: 76). By participating in the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INC) and engaging with a broad range of stakeholders involved in the process, we contextualise how waste pickers are named and framed across official, informal and draft documents and statements; analyse the performative aspects of waste picker advocacy; and point to the “scale work” they engage in to leverage influence across national, regional and international levels.

Methodology

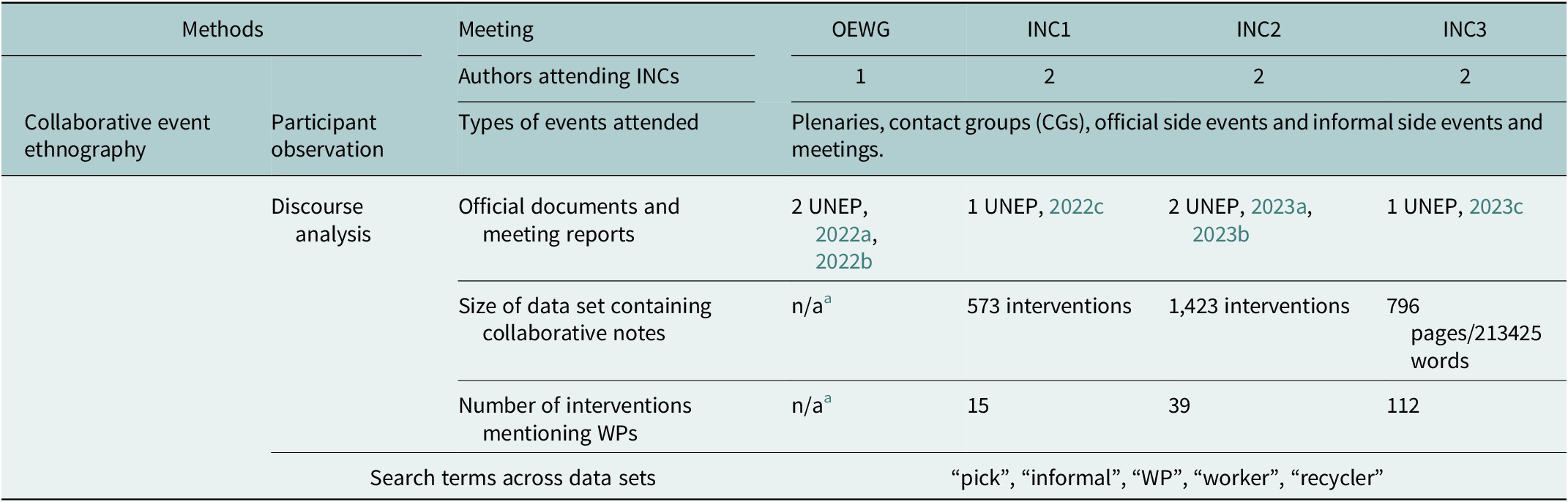

This article draws on a range of social science methods, including participant observation, collaborative event ethnography (CEE) and discourse analysis (Table 1). By analysing official documents and meeting reports alongside collaborative note sets of Member State (MS) and observer interventions from INC1 to INC3 (Cowan and Tiller, Reference Cowan and Tillerforthcoming), we gain a greater understanding of the prevailing narratives and terminologies throughout the plastics treaty process. While interventions from plenary sessions are streamed online, interventions in contact groups (CGs) are restricted to in-person attendees and specific content from these cannot be publicly shared. Thus, below, we refer to MS interventions in plenary followed by session, date and/or meeting, while from CGs, we do not specifically quote MSs. CEE was carried out following the tradition of researchers like Campbell et al. (Reference Campbell, Corson, Gray, MacDonald and Brosius2014), Brosius and Campbell (Reference Brosius and Campbell2010), Mendenhall et al. (Reference Mendenhall, Tiller and Nyman2023) and Cowan et al. (Reference Cowan, Holmberg, Nøklebye, Rognerud and Tiller2024) who have employed such methods at GEG meetings.

Table 1. Methodologies and data sets

a n/a, not enough data.

Although the plastics treaty INCs are slightly smaller than some UN Conference of the Parties (COPs), they are of significant size, with thousands of attendees engaging in hundreds of meetings. As a small team with multiple responsibilities, we were under no illusion that we could attend or capture every interaction, even those restricted to waste pickers. Further, for some bilateral meetings between waste pickers and MSs or the INC Secretariat, the presence of additional researchers would have been burdensome. Our presence at different waste picker interactions was measured and methodological, involving attendance at open fora and selective participant observation in more closed spaces. The active, participatory nature of involvement should also be stressed – rather than detached observation, we often advised waste pickers and even provided informal translation services. This was part of a reciprocal relationship where we sought to make ourselves useful, and our research beneficial, to our research participants. To a certain extent, we also let ourselves be led by waste pickers: meetings and activities that were important to them also became important for us, and conversely, we did not have much to do with actors whom waste pickers did not seek to influence or create alliances with. Close engagement with waste pickers before and during the INC process may have influenced our analysis, although we were able to conserve a critical distance as independent researchers. Our status as researchers from the United Kingdom and NorwayFootnote 2 may also have influenced the framing of the research and the information shared with the authors.

By focusing on one specific stakeholder, cross-checking each other’s notes and triangulating these with CSOs’ notes and official meeting proceedings, we hope to offer a thorough, if not exhaustive, account of waste picker engagement in the plastics treaty process up to and including INC3. In spreading our focus over consecutive INCs, we “reveal critical relationships and individual agency within a meeting” and “illuminate…changes in governance over time and space” (Corson et al., Reference Corson, Campbell and MacDonald2014:31). In the spirit of O’Neill et al. (Reference O’Neill, Suiseeya, Bernstein, Cohn, Stone and Cashore2013), we use CEE to track the processes by which waste pickers have gained prominence as an important stakeholder in plastics treaty discussions.

Recognising the importance of community peer review (Liboiron, Reference Liboiron2022: 138), we invited technical staff from the International Alliance of Waste Pickers (IAWP) to review this article.

Waste pickers’ engagement in the plastics treaty process

Waste pickers’ involvement in the plastics treaty negotiations began at the United Nations Environment Assembly (UNEA) 5.2 in Nairobi in February/March 2022, building on waste pickers’ participation in climate change negotiations from 2009 (COP15) onwards. The UNEA 5.2 resolution 5/14 does not specifically mention waste pickers or just transition but recognises “the significant contribution made by workers in informal and cooperative settings to the collecting, sorting and recycling of plastics in many countries” and recommends that the INC “consider lessons learned and best practices, including those from informal and cooperative settings” (UNEP, 2022a) (Annex 1). This was partly a result of the IAWP lobbying at UNEA 5.2, where nine waste pickers and their associated technical team put forward a series of demands and suggestions surrounding waste picker involvement in the plastics treaty.

The IAWP is a relatively new organisation that nevertheless builds on decades of transnational waste picker organising. The First International (and Third Latin American) Conference of Waste Pickers was held in Bogotá in 2008. During subsequent years, meetings of an Interim Steering Committee for a nascent international waste pickers’ organisation were held in Durban (2009), Belo Horizonte (2010) and Bangkok (2011). In 2009, waste pickers sent an observer delegation to the COP15 Climate Change Conference in Copenhagen under the banner of the “Global Alliance of Waste Pickers”, as the IAWP was initially known. This was the first organised involvement of waste pickers at a GEG forum and set a precedent for attendance at subsequent climate change COPs and other international environmental events.

The IAWP’s 460,000-strong membership is spread across Africa (65,625), Asia Pacific (292,094), Europe (5,200), Latin America (94,208) and North America (623). It launched its constitution in October 2022 and hosted its first elective congress in May 2024. According to its constitution, the IAWP is a “representative structure and mouthpiece for waste pickers” that “will defend their work and its recognition, in pursuit of public policies that improve the working and living conditions of the recyclers of the world”. It is effectively a “trade union of waste pickers” whose “scope covers the waste pickers represented in the organisations that act in the defence of subsets of waste pickers…throughout the world”. Its member organisations can be of local, national or regional scope and must meet a set of criteria, including that they principally represent informal waste pickers, be democratic and accountable and be membership-based organisations (cooperatives, trade unions and associations). The Congress is the Alliance’s highest decision-making body with affiliates apportioned voting delegates based on the size of their memberships. At least 50% of the Congress delegates should be women, non-binary or trans workers. The Congress elects an Executive Council (President, Vice President and Treasurer), which is geographically balanced and hires and oversees a General Secretary and Secretariat.

The IAWP has sent sizeable and geographically representative observer delegations to the INCs in Uruguay, France and Kenya, including two democratically selected representatives per region. Some of these waste pickers have been financed by United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), and others have formed part of national delegations (Argentina, South Africa and Brazil). The increasing visibility and importance of waste pickers at the plastics treaty negotiations have been remarked upon; in the words of one MS in their intervention during the INC3, “waste pickers give the plastics treaty a human face” (MS, CG1, INC3). In the following sections, we examine the influence of naming, performance and scale as waste pickers have gained increasing prominence as the human face of the plastics treaty.

Naming

This section documents the changing ways that waste pickers have been referred to in official documents and interventions in the plastics treaty negotiations up to and including INC3. As we shall see, the terminology used to describe waste pickers has evolved in a non-linear fashion. There has been slippage between explicit mentioning of waste pickers as “stakeholders” who are key to achieving a just transition and the subsumption of waste pickers into broader groupings of “waste workers” and “workers in informal and cooperative settings”. Waste pickers have also been mentioned with reference to ensuring a just transition across the plastics lifecycle, for workers, communities, Indigenous Peoples, women, children and people in vulnerable situations. However, what is clear is the way that waste pickers themselves have increasingly focused their efforts on the inclusion of the word “waste picker”, even to the exclusion of other language alternatives and translations, the most common of which being the Spanish reciclador. This is partly due to the confusion generated by the latter term, which translators unversed in the nuances of waste politics often translate simply as “recyclers”, a misleadingly broad term that can include a wide range of actors, from waste pickers to multinational companies.

“Waste pickers” are defined by the IAWP as individuals involved in the collection, segregation, sorting, transportation and sale of recyclables in an informal or semiformal capacity as own account workers, within the informal or semi-formal sector for sorting, recovery and recycling, and any of the above who have been integrated in municipal waste management or occupy new roles in recycling organisations (IAWP, 2022a, 2022b). Various terms exist across geographies and languages to describe individuals engaged in extracting materials from waste streams for personal use or sale. Some terms specify the type of material collected, while others are preferred for how they frame the activity. Context-dependent examples include “rag picker”, “reclaimer”, “recycler”, “salvager”, “canner”, “waste collector” and “waste picker” in English; “cartonero”, “clasificador”, “trapero”, “minador” and “reciclador” in Spanish; and “catador de materiais recicláveis” in Portuguese. Other terms, such as “scavenger” and “rummager” (hurgador), have been considered pejorative and rejected by some involved in this activity (Samson, Reference Samson and Samson2009). In cities and countries worldwide, there have been discussions among individuals performing this vital labour about what to call themselves. The term “waste picker” was officially adopted by waste pickers from over 30 countries at the First World Conference of Waste Pickers in Bogotá in 2008 to strengthen regional and global networks under a unified umbrella terminology (WIEGO, 2023).

Prior to INC1, an open-ended working group (OEWG) preparatory meeting was hosted in Senegal, during which the need for a future instrument to specifically and adequately reflect the role of waste pickers and informal workers in the fight against plastic pollution was underlined (UNEP, 2022b). Subsequently, INC1 in Uruguay showed widespread support for recognising and including all relevant stakeholders in the negotiations, with a specific emphasis on “informal waste pickers”, Indigenous Peoples and other disadvantaged groups (UNEP, 2022c). The significance of waste picker inclusion and participation to ensuring a just transition was emphasised in MS interventions with relation to opening statements (8),Footnote 3 scope and objective (3), stakeholder engagement (2) and sequencing and recommended further work (2). Importantly, it was recognised that waste pickers are one of the stakeholder groups most vulnerable to policy changes stemming from the plastics treaty (Kenya, Plenary, 01.12.22). Several MSs called for specific measures to foster the inclusion of waste pickers across plenary sessions, including finance and capacity building (Chile and Columbia, 28.11.22; Uruguay 30.11.22), ensuring decent working conditions (Burkina Faso, 02.12.22), participating in the negotiations (Kenya, 01.12.22) and establishing a “fund to manage legacy plastics (…) available to all waste pickers” (Ghana, Plenary, 01.12.22).

An Options Paper released ahead of INC2 presented a range of options related to “facilitating a just transition, including an inclusive transition of the informal waste sector” under possible core obligation 11 (UNEP, 2023a) (Annex 1). It reflected an inconsistency in terminology used by the MS, ranging from broadly enabling a fair and equitable transition for industries and affected workers to specifically improving working conditions for waste pickers, integrating the informal waste sector and funding infrastructure and skills for informal waste pickers through the operationalisation of extended producer responsibility (EPR) schemes. On the second day of INC2, the IAWP outlined what a just transition meant for them: “You must integrate (…) and work with us to design and add value to recyclables. We need fair prices, environmental fees (…), access to materials and infrastructure, and social welfare and security, both in the treaty and nationally”, ending their intervention with the slogan “Without waste pickers, a treaty is rubbish” (IAWP, 31.05.23, Plenary). In CG1, discussion about waste pickers revolved around protecting human and workers’ rights, with several MSs from the African Group, Group of Latin American and Caribbean Countries (GRULAC) and Western Europe calling for integration guidelines, fair remuneration and ensuring that waste pickers are included in new systems, such as EPR.

The Zero Draft text released in advance of INC3 outlined options for improving working conditions for workers in waste management under provision 12 on “just transition” (UNEP, 2023c). Surprisingly, however, despite being mentioned by many MSs at INC2 (including interventions from 14 individual MSs and on behalf of three regional groups), there was no explicit reference made to waste pickers, marking an apparent weakening of language when compared with the Options Paper; in the just transition section, those singled out for special consideration were “women and vulnerable groups, including children and youth”. In the body of the provision, meanwhile, reference was made to “workers in the waste management sector”, “workers across the value chain” and “workers in informal and cooperative settings”, a return to the language used in UNEA Resolution 5/14. In response to the removal of specific references to waste pickers, the IAWP went into INC3 with three requests: the incorporation of the term “waste picker” into the treaty text; cross-referencing of just transition across other relevant provisions (e.g. EPR and waste management); and the inclusion of definitions of “waste pickers”, “just transition” and “workers in informal and cooperative settings”.

The importance that the IAWP placed on the inclusion of the term “waste picker” became clear in a pre-INC3 meeting of GRULAC, in which CSOs were invited to make interventions at the end. A waste picker leader lifted her hand to make an intervention:

“We have heard waste pickers mentioned many times in different speeches, plenaries, and other INC processes but today we are very worried that in the Zero Draft there is no mention of waste pickers, just informal, formal, and cooperativized workers, and we aren’t always included in these terms since we aren’t even recognised at the ILO” (IAWP, GRULAC Regional Meeting, 12.11.23, translation by author).

It is interesting to note here that although the intervention was made in Spanish, the English term “waste picker” was used, highlighting the linguistic hegemony that the English language term had come to assume for the IAWP, with equivalents in Spanish and other UN languages a secondary concern. In advocating for the use of an occupational term (waste picker) and arguing for the inclusion of the IAWP definition of such a term, waste pickers at the plastics treaty engage in “boundary work”, defined by Langley et al. (Reference Langley, Lindberg, Mork, Nicolini, Raviola and Walter2019) as “a purposeful individual and collective effort to influence the social, symbolic, material, or temporal boundaries, demarcations and distinctions affecting groups, occupations, and organisations”. The IAWP’s call for explicitly mentioning waste pickers across the treaty text was echoed by several MSs of the African Group and GRULAC in CG discussions related to provisions on just transition, waste management, EPR, chemicals and polymers of concern and problematic and avoidable plastic products. In the revised Zero Draft text that was released following INC3, we can see that the emphasis placed by the IAWP on specifically naming waste pickers bore fruit, with the group being mentioned in bracketed text seven times in the just transition provision as well as in the Preamble, Provision 7 (EPR), Provision 9 (Waste Management), Part III.1 (Financing), Part IV 1. (National Action Plans), Part IV 3. (Reporting on Progress), Part IV 6. (Information Exchange) and Part IV 8. (Stakeholder Engagement) (UNEP, 2023d).

Performance

The IAWP has co-organised several official and informal side events at the INCs in collaboration with other CSOs and MSs. In an informal side event at INC1, the IAWP launched the Group of Friends of Waste Pickers (inspired by the Groups of Friends of Indigenous Peoples established at the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation in 2019), while at INC2, the IAWP co-hosted an informal side event with Brazil, Kenya and South Africa focused on the broader aims of the Just Transition Initiative, launched by the latter two MSs. At INC3, the IAWP hosted an informal side event at the Brazilian Embassy in Nairobi, entitled “Uniting for a Just Transition”. Marking the one-year anniversary of the IAWP constitution (adopted 17 October 2022), the side event was an invitation both to celebrate and to hear the IAWP present its position paper on a Just Transition for Waste Pickers under the Plastics Treaty (IAWP, 2023). A theatrical performance entitled “Who knows it feels it: A waste picker’s perspective for a just transition” was also organised on three separate occasions prior to INC3 by researchers from the University of Portsmouth, a theatre for development specialist, Grid-Arendal, the Nairobi-based Social Justice Centre Travelling Theatre and the Kenyan National Waste Pickers Association. In the following sections, we draw on event ethnography conducted at the latter two events during INC3, on 13 and 19 November 2023, to explore the importance of performance for waste pickers as they advance their demands and strengthen their position in the plastics treaty process.

The Uniting for a Just Transition event at the Brazilian Embassy sheds light on the politics of performance and provided an opportunity to put waste pickers back at the centre stage of ensuring a just transition in the plastics treaty. Although representatives from the scientific, business, environmental and Indigenous Peoples’ communities were invited to the event, two groups were afforded priority in terms of spoken interventions and seating: waste pickers and MS delegates. It was symbolically important that waste pickers took centre stage at the embassy event. Indeed, one of the Kenyan waste picker leaders told us that normally a waste picker wandering around the UN district of Nairobi would likely be harassed by police and security, never mind being invited inside an embassy. It was particularly symbolic that the host of the event was a Brazilian waste picker who also formed part of the Brazilian MS delegation, and he made sure that the invitation to the event was extended not only to Kenyan waste picker observers at the INC3 but to “rank and file” waste pickers from the Kibera slum: thirty of them, clad in their trademark olive green uniforms, descended from a bus and found their names on the guest list. MS delegates were, meanwhile, given priority because they were those that the waste pickers needed to influence to get their messages across in the treaty negotiations and as a way of thanking those that had already voiced their support.

In the event, waste pickers from the United States, Italy, Bangladesh, Brazil and Senegal delivered key points from the IAWP position paper with which they particularly identified, each intervention involving a slightly different combination of rehearsed and improvised speech. This meant that each speaker could play to their strengths: some were comfortable giving long, rousing political speeches, while other presentations were more technical or got to the point, and indeed to the heartstrings, in just a few words. Full copies and executive summaries of the official IAWP position paper on just transition were then distributed to delegates. This format facilitated two important aspects of waste picker claims to be legitimate (local) knowledge holders: they could speak from the heart about their lived experiences and provide a fleshed-out, technical, fully referenced paper on just transition that could inform MS positions. The role of waste pickers as important knowledge holders was highlighted as O’Hare shared the authors’ policy brief on just transition but emphasised that most of what he had learned from working with waste pickers had indeed come from waste pickers, as co-participants in the creation of research and, in some cases, now university researchers themselves.

The purpose of the theatrical performance, entitled “Who knows it feels it: A waste picker’s perspective for a just transition”, was to “amplify the voices of waste pickers to the policy- and decision-makers who have the power to bring about systemic change”.Footnote 4 The theatre troupe and researchers spent a week at Nairobi’s Dandora landfill developing a series of skits with the waste pickers, inspired by, and recreating, the types of situations that they find themselves in during their everyday lives. These included instances at the landfill where waste pickers were injured because of a lack of personal protective equipment, an attempt to negotiate a sale of plastic with a recycling intermediary, a confrontation with a homeowner who renegades on payment for their door-to-door collection and a frustrating attempt to obtain a meeting with a municipal official.

The theatre piece invited the audience to participate by intervening as waste pickers in scenes if they thought that they could induce a different ending. In this, the performance partly followed the script of “legislative theatre”, a concept coined by Brazilian dramaturg Augusto Boal, composed of four parts: watching an original play based on community members’ lived experiences and problems, acting on stage to intervene in the play, testing ways to address the problems and then proposing and voting on policy changes. To a certain extent, the play bridged theatrical performance and what sociologist Jeff Alexander has called “cultural performance”, defined as “the social process by which actors, individually or in concert, display for others the meaning of their social situation” (2006:32). An effective performance, Alexander argues, should be a plausible one, thus depending “on the ability to convince others that one’s performance is true, with all the ambiguities that the notion of aesthetic truth implies” (ibid).

Alexander’s analogical model relies on a separation between theatrical and cultural performance in what he calls “complex societies”. In “Who knows it, feels it”, both types of performance are merged, and the authenticity, success and truth of the performance rely not only on waste pickers’ ability as actors but also on their ability to faithfully reproduce their own life experiences. Alexander’s framework can also be useful for understanding the efficacy of the performance, particularly the aspect of psychological identification, whereby the audience identified with and acted out the role of waste pickers when taking the stage. One of the authors experienced this himself, when he trialled an alternative method of gaining a meeting with the municipal official: staging a peaceful protest involving the singing of the Kenyan waste picker anthem to attract attention. This was then met with an improvised response from the waste pickers, some of whom turned into convincing security forces who arrived to violently break up the demonstration, thus giving the audience an insight into the challenges of using protest as a method of advancing demands in Kenya.

Alexander’s framework of cultural performance points to some of the performative aspects of waste picker interventions in the treaty process more broadly. We agree with Jeff Juris in his work on the Occupy movement that social movement practices might be thought of as operating along a continuum from more to less performative, with cultural performance a means through which “alternative meanings, values, and identities are produced, embodied and publicly communicated” (2015, 82). Campbell et al. (Reference Campbell, Corson, Gray, MacDonald and Brosius2014), meanwhile, have drawn attention to the dramaturgical aspects of GEG, through their event ethnography of COP10 of the Convention on Biological Diversity. As they conceive it, “a dramaturgical perspective directs us to analyse how meeting sites are managed and roles performed, in ways that are not only constitutive of the subject identity of participants, but shape the legitimation of knowledge” (Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Corson, Gray, MacDonald and Brosius2014, 7). Understanding the “politics of performance” involves examining which actors can speak in what setting, how events are staged and when aspects of the spectacular are present (ibid) and it is not only in strictly theatrical performances, that “different actors perform their policy preferences in front of an audience” (ibid).

Multi-scalar alliances

We have earlier noted how waste pickers engage in “boundary work” to influence occupational categorisations and definitions. In this final section, we discuss the importance of “scale work” as waste pickers seek to influence the plastics treaty through multi-scalar alliances. With this term, we denote, first, the way that the IAWP has effectively “scaled up” organising tactics that they have already finessed at national and regional levels, such as strategic alliances with CSOs, MSs and industry actors. Second, waste pickers also “scale down”, which involves both taking the matters discussed at the plastics treaty negotiations back to their grassroots for input and consultation and attempting to leverage progress in the treaty negotiations into tangible gains at a national level. We will thus address the way that waste pickers engage these different scales simultaneously to their advantage.

As part of the plastics treaty process, waste pickers engage in a range of strategic alliances with other CSOs. Joint interventions have, for example, been made with trade union representatives, stating the importance of a just transition for all plastics workers (Figure 1). Multinational companies involved in the Business Coalition for a Global Plastics Treaty have meanwhile launched the Fair Circularity Initiative. The initiative is rooted in the IAWP’s EPR position and articulates a commitment to improving the human rights for workers like waste pickers that are indirectly involved in their supply chains through the recovery of recyclable packaging and its reincorporation into new products. The IAWP’s engagement in the plastics treaty process builds on the consultative work leading up to their EPR position (Cass Talbott et al., Reference Cass Talbott, Chandran, Allen, Narayan and Boampong2022).

Figure 1. IAWP aligning with other civil society actors to amplify shared priorities.

The IAWP often treads a fine line in manoeuvring between actors with different interests in the treaty process but builds on decades of experience working with different actors and potential allies. For instance, the Latin American and Caribbean Waste Pickers Network (Red LACRE) was a founding member of the Regional Recycling Initiative (now Latitude R), joining companies and organisations like the World Bank, Coca-Cola and PepsiCo to promote examples of “inclusive recycling”. Since these actors can, in other circumstances, be locked in more agonistic relationships with waste pickers, Zapata Campos et al. (Reference Zapata Campos, Carenzo, Kain, Oloko, Reynosa and Zapata2021) see such alliances as an example of what Gibson-Graham et al. (Reference Gibson-Graham, Hill and Law2016) have called “multispecies communities”, in which “organisations with antagonistic interests converge temporarily” (2020: 593). As Zapata Campos et al. write, Red Lacre has been able to channel the work carried out in the Latitude R partnership, such as reports and best inclusive recycling practices supported by big business, into more inclusive recycling policies in a host of countries (ibid). Waste picker organisations are both wary that such companies may be engaging in “greenwashing” and think that it is only right that waste pickers should receive funds and support, however limited, from companies for whom they have for decades delivered an environmental cleanup service free of charge. Alliances with environmental groups can also be tense, since not all are favourable to recycling nor demand that the phase-out of plastics be contingent on a just transition for impacted workers. These are the kinds of tensions that the IAWP negotiates as they scale up alliance strategies. We would suggest that waste pickers maintain what Zapata Campos et al. (Reference Zapata Campos, Carenzo, Kain, Oloko, Reynosa and Zapata2021) have described as a policy of establishing open and diverse relationships with a range of different actors as part of a “grassroots governmentality”.

Building alliances with CSOs and industry actors can amplify shared priorities in the plastics treaty negotiations. Yet perhaps even more influential in the negotiations are alliances with MSs. Our analysis shows that some of the most supportive MSs often comes from groups of countries where waste pickers have strong organisations, such as within the GRULAC and the African Group. This can be seen as a result of waste pickers’ work over decades, where local and national relationship building, as well as participation in developing national waste management and environmental legislations, is scaled up to the global level. Strong sub-national and city-based achievements for waste pickers do not always scale up to favourable national MS positions, however. This is the case for India, for example, where the campaigning of waste picker organisations such as the KKPKP, Hasiru Dala and SWaCH in cities like Pune and Bangalore has resulted in inclusive legislation and the participation of waste picker cooperatives in municipal solid waste management systems (Chikarmane, Reference Chikarmane2012; Shankar and Sahni, Reference Shankar and Sahni2018). However, India has yet to emerge as a strong supporter of waste picker inclusion in the plastics treaty negotiations. As indicated by the hosting of an IAWP event in the Brazilian Embassy, Brazil, on the other hand, has been supportive of waste pickers in the treaty process, a fact not unrelated to the inclusive waste management legislation passed by various Workers’ Party (PT)-led governments and the strong personal relationship between President Lula da Silva and Brazil’s thousands-strong waste pickers (catador) movement.Footnote 5 Nationally, recent waste picker campaigns have focused on the inclusion of waste pickers in EPR legislation in various countries (e.g. Najib and Patil, Reference Najib and Patil2023), something with relevance for the plastics treaty given the likely inclusion of an article on EPR.

At the same time, as waste pickers scale up existing regional organisation strategies, waste pickers also “scale down”, returning to their grassroots for updates and consultations and attempting to transform international advances into local gains. Waste pickers attending the INCs were encouraged to report back findings to their home country organisations and gather input and advice for further negotiations (Figure 2). This was an important step for maintaining a link with the grassroots and strengthening the democratic and representative character of waste picker participation in the plastics treaty process. At monthly online plastics working group meetings with simultaneous translation for the IAWP and their allies, IAWP representatives were asked to report back any conversations that they had with their national membership on plastics treaty developments. Such a modality of virtual work had grown out of the pandemic and enabled more inclusive organising and regular communication between waste pickers dispersed all over the world.

Figure 2. Senegalese waste picker leader Harouna Niass reporting back to Senegalese waste pickers following INC3. Photograph: Amira El Halabi.

Waste pickers also attempted to lobby at a national level to secure improvements, leveraging their prominence and alliances at the INCs as they had previously tried to scale down regional partnerships like Latitude R. In Uruguay, host to INC1, an obvious disconnect emerged between the position of Uruguay in the plastics treaty negotiations (where it was and continues to be an important supporter) and the direction in which national waste policy was moving: away from inclusive recycling, towards more pro-business schemes. Whereas the current Uruguayan EPR scheme involves waste picker cooperatives but has low levels of recovery, Plan Vale, a new scheme launched by the Uruguayan Producer Organisation, the Chamber of Industry, involves siphoning off the most valuable materials to a semi-automatic Deposit Return Scheme (DRS) run by a multinational company (Matonte-Silva and O’Hare, Reference Matonte-Silva and O’Hare2022).

In an official side event at INC1, hosted by the Uruguay Environment Ministry, a Latin American waste picker leader made an intervention from the floor, pointing out how the plan stood to dispossess and negatively impact Uruguayan waste pickers. Several inconsistencies were pointed out in a subsequent meeting between the Uruguayan waste pickers, IAWP colleagues, allies and public and private sector actors involved in Plan Vale; while Uruguay had just agreed to join the Group of Friends of Waste Pickers, waste pickers had not been consulted or involved in the Plan Vale policy process. Moreover, as waste pickers were gaining recognition and influence in the plastics treaty negotiations, several multinational companies that would be making contributions to the Uruguayan EPR scheme had also signed up to the abovementioned Fair Circularity Initiative. While representatives from Plan Vale seemed to take on board the spirit of these comments, Uruguayan waste pickers told the authors that no substantive changes were subsequently made to Plan Vale nor had waste pickers been meaningfully consulted by the time of this article’s submission. Meanwhile, in Chile, attempts to scale down international treaty advances fared somewhat better. The national leadership used contacts established with companies signed up to the Fair Circularity Initiative to press for improvements in a new legal EPR programme to make it more inclusive and responsive to waste picker needs. As a result, the EPR law stipulated that waste pickers would receive a minimum payment per kilo of packaging waste recovered. The contrast between the two cases demonstrates that waste pickers are not always successful in scaling down agreements and precedents established at an international level to national contexts. Strong leadership at the national level and the openness of national governments to including waste pickers in policy design are two important factors that can determine positive or negative outcomes of such “scale work”.

Concluding remarks

Past the midway point of the plastics treaty negotiations, this article has offered a preliminary analysis of the ways in which waste pickers have influenced the plastics treaty negotiations. While being active and visible at the INCs does not automatically translate into influence (Betsill and Corell, Reference Betsill and Corell2001), we have shown that waste pickers have engaged in boundary and scale work to form strategic alliances with CSOs and MSs to ensure that their interests are placed and remain on the negotiating agenda. Their influence becomes visible as MSs repeatedly and passionately call for the inclusion and explicit mention of waste pickers across the treaty text. The recognition of waste pickers has been non-linear across official INC documents, with a notable weakening of the negotiated language in the Zero Draft text as compared to the Options Paper. Yet it becomes evident that MS interventions have largely gone from portraying waste pickers as “merely” vulnerable workers to having specific rights as human beings, workers and local communities with global reach, whose participation as key knowledge holders is an essential element of developing and implementing a treaty which enables a just transition towards ending plastic pollution.

As argued by Ciplet (Reference Ciplet2014) in the climate negotiation space, recognition in negotiated text can be leveraged to put pressure on governments and businesses at local and national levels. We observe that waste pickers do this by scaling down the matters discussed at the plastics treaty negotiations to their grassroots communities for consultation and leveraging tangible gains at national levels. However, international commitments to ensuring a just transition for waste pickers do not always reflect national action, as illustrated by the example of Uruguayan waste pickers being excluded from a privately run DRS system. At the same time, multinational companies are agreeing on principles for fair circularity that are strongly influenced by waste picker positions, which could provide a starting point for co-developing guidelines for a just transition for waste pickers in the plastics treaty. Looking ahead, to ensure a just transition in the plastics treaty, waste pickers must be recognised as key stakeholders in the development and implementation of strategies to reduce plastic pollution, prioritising meaningful participation, social protection, decent work and safeguarding measures to avoid negatively affecting waste pickers’ livelihoods when moving towards safe and equitable zero waste systems, involving reuse, refill and recycling (O’Hare et al., Reference O’Hare, Nøklebye, Stoett and Korsten2023). It is yet to be seen how a just transition will be addressed in the final treaty text. Its impacts on people and communities involved in waste picking will thus largely depend on whether the treaty and its provisions will be legally binding based on globally agreed goals or based around voluntary and nationally determined targets, as well as MSs and local municipalities’ capacities to implement and monitor these.

This article has engaged with how waste pickers have worked to place their demands for a just transition on the plastics treaty agenda, by focusing on being cross-referenced across the plastics treaty text, positioning themselves front and centre stage in effective performances in parallel to the negotiations and scaling up and down their alliances and strategies simultaneously to work towards a just transition at local, national and international levels. By doing so, we have explored some of the processes through which waste pickers have become the human face of the plastics treaty and reiterated their role as an important stakeholder group whose rights and knowledge must be included and protected. The evidence of waste picker influence that we demonstrate in this article can also be used to justify the resources that the IAWP have sunk into the plastics treaty process, the fruits of which might take years to trickle down into the lives of many individual waste pickers. We hope that the conceptual triad of naming, performance and scale that we have developed can be useful for analysing the actions, strategies and influence of other groups involved in GEG advocacy, including Indigenous Peoples, trade unions and environmental groups. As we move towards the crucial final stages of the plastics treaty negotiations with ambitions to reach an agreement by the end of 2024, other avenues for future research include monitoring waste pickers’ role and influence in the plastics treaty process, as well as identifying how proposed control measures and means and mechanisms of implementation may influence the multiple dimensions of just transition for waste pickers and other peoples and communities in the transition towards ending plastic pollution.

Open peer review

To view the open peer review materials for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/plc.2024.12.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the UNEP, but restrictions apply to the availability of some of these data, which were used for the current study and so are not publicly available. Some of the data are, however, available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request and with the permission of UNEP.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the International Alliance of Waste Pickers for their collaboration with this article. We would also like to thank María José Zapata Campos, Taylor Cass Talbott, Aase Jeanette Kvanneid and Marianne Mosberg for initial input or critical readings.

Author contribution

P.O. and E.N. conceptualised the article; P.O. and E.N. collected the data and prepared the original draft; P.O. and E.N. contributed to formal analysis; and P.O. and E.N contributed to the writing, reviewing and editing of the article. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Financial support

This work was supported by the Norwegian Development Assistance Program Against Marine Litter and Microplastics and the Royal Norwegian Embassy in New Delhi (E.N., grant number IND-22/0007); the Research Council of Norway (E.N., grant number 302575); and a UKRI Future Leaders Fellowship (grant number MR/S03501X/1).

Competing interest

The authors declare no competing interests exist.

Ethics statement

This research has been conducted in line with the Norwegian research ethics guidelines of the National Committee for Research Ethics in Science and Technology (NENT) and the research ethics guidelines of the National Committee for Research Ethics in the Social Sciences and the Humanities (NESH). Research ethics approval for the UKRI Future Leaders Fellowship (grant number MR/S03501X/1) was sought and approved by the School of Philosophical, Anthropological and Film Studies Ethics Committee, acting on behalf of the University Teaching and Research Ethics Committee of the University of St Andrews, under approval code SA15058.

Annexes

Annex 1. Terminology related to waste pickers in key INC documents

Sources: UNEP (2022) UNEP/PP/OEWG/1/INF/1. pp. 3–4; UNEP (2023) UNEP/PP/INC.2/4. p. 12; UNEP (2023) UNEP/PP/INC.3/4. p. 19.

Comments

No accompanying comment.