Introduction

Advances in neurotechnology and artificial intelligence (AI) are challenging traditional boundaries of our brains and mental lives. Academic analyses of the ethical and legal implications of these advances in neurotechnology have now also spawned several initiatives at the national and international policymaking and lawmaking levels.

In the scholarly literature, discussions of rights to our brains and mental experiences in human rights mainly focus on the legal protection of mental integrity, mental privacy, and cognitive liberty by established human rights instruments such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), the American Convention on Human Rights (ACHR), the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), and the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union (CFR).Footnote 1 Meanwhile, the United Nations,Footnote 2 the Inter-American Juridical Committee,Footnote 3 the Committee on Bioethics of the Council of Europe,Footnote 4 UNESCO,Footnote 5 as well as the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)Footnote 6 have each initiated projects to ascertain the protective scope of established human rights in respect of thoughts, emotions, and other mental states, both now and in the future. For example, according to the Committee on Bioethics of the Council of Europe, there is a need to assess

whether these issues can be sufficiently addressed by the existing human rights framework or whether new human rights pertaining to cognitive liberty, mental privacy, and mental integrity and psychological continuity need to be entertained in order to govern neurotechnologies. Alternatively, other flexible forms of good governance may be better suited for regulating neurotechnologies.Footnote 7

Neurotechnologies have been scrutinized for raising human rights implications, in particular because neurotechnologies provide the capability to (1) access someone’s mental states, (2) verify subjective (or first-person) reports regarding the nature and content of those states, (3) contest first-person authority regarding mental states by overriding such introspective reports, and (4) control decoded mental states by providing input behaviorally or through direct brain stimulation. But how exactly might neurotechnologies present human rights challenges?

Ethical challenges have emerged in all domains of application, including the medical, the consumer domain, and the use of neurotechnologies by state actors such as in military and criminal justice contexts.Footnote 8 Let us look at this latter domain in greater detail.

Scholarly consideration has been given, for example, to the use of brain-reading neurotechnology in the context of criminal justice.Footnote 9 The primary, though still not practically applicable, ethical concern in this domain is the possibility that during the investigation of crimes, the police might employ some form of brain-reading neurotechnology to make inferences about the mental processes of suspects in order to advance their investigation. An even more speculative concern is that in the future, neurotechnologies might be employed as a sentencing option; for example, a closed-loop device could be used to monitor the brain of an offender and intervene upon it in order to avert an angry outburst that might precipitate an offense.Footnote 10 Such scenarios give rise to questions of mental privacy, cognitive liberty, and mental integrity, and it is not hard to imagine examples from the other domains mentioned in the last paragraph that might generate disquiet.

In view of the technological developments and emerging risk assessment evaluations, questions arise as to whether existing human rights are sufficient to protect our brains and minds. While some authors have argued so, others advocate for the introduction of novel brain-specific rights, so-called “neurorights.”Footnote 11

Whether or not neurorights are needed is a question currently being addressed by academics as well as national legislators and intergovernmental organizations. For example, national legislators in Chile have been working on the implementation of neurorights into their national legal systems within the framework of a constitutional reform.Footnote 12 At the level of human rights, the United Nations, the Inter-American Juridical Committee, and the Council of Europe are exploring whether the established scope of existing rights and freedoms provides sustainable legal protection to our brains and minds in view of emerging neurotechnologies.Footnote 13 Recently, UNESCO, too, contributed to a report on the risks and challenges of neurotechnologies for human rights.Footnote 14

While these policy initiatives are still in the making, central notions in this area, such as “mental privacy,” “mental integrity,” and “cognitive liberty,” are not subject to consensus. Notably, there is a relative paucity of interdisciplinary theorizing and conceptualization, integrating perspectives from science and technology (neuroscience, neuroengineering, and computer science), philosophy, ethics, legal philosophy, and law.

This paper constitutes a concerted interdisciplinary effort by a group of scholars from different academic fields—inter alia philosophy, biomedical ethics, law, neuroscience, cognitive science, medicine—in mapping the ethical and legal foundations of neurorights with the purpose to facilitate international discussions and policy initiatives at various levels.Footnote 15

To this end, we first briefly introduce the notion of neurotechnology and its current applications. We then map the current state of the ethical and legal debate on the relation between neurotechnologies and human rights and critically appraise the notion of neurorights. In the second part, we will provide a philosophical and ethical analysis of three key notions in the neurorights debate, namely mental privacy, cognitive liberty, and mental integrity. Finally, in the third part, we will examine the potential legal implications of this integrated conceptual understanding, particularly regarding current rights-based policy approaches to “neuroprotection.” We will focus on three main areas of human rights significance: mental privacy, mental integrity, and cognitive liberty.Footnote 16

Neurotechnologies and Their Applications

Currently, several types of neurotechnologies are under development. While there are many ways in which we can intervene in the brain through pharmaceuticals, psychotherapy, and other means, the term “neurotechnology” denotes devices that measure brain structure or function (particularly brain activity) or intervene into brain activity (e.g., through electrical stimulation). Typical examples of neurotechnology are brain–computer interfaces (BCIs), that is, systems that measure and analyze brain activity to control an “effector” (such as a robotic arm or a software for text generation).

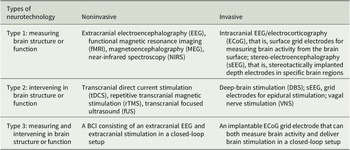

Three central types of neurotechnology are to be distinguished (see Table 1):

-

1. Devices that can monitor brain activity, that is, neural correlates of mental states and behavior

-

2. Devices that can intervene into brain activity, for example, through electrical stimulation

-

3. Bimodal devices that combine types 1 and 2

Table 1. Three central types of neurotechnology

Apart from their use in medicine, neurotechnologies can be used in other domains such as the consumer market (e.g., BCIs for gaming, education, or meditation),Footnote 17 criminal justice (e.g., potentially as tools for lie detection),Footnote 18 and the military (e.g., potentially for cognitive enhancement or covert brain-to-brain communication).Footnote 19 Examples of type 1 include passive BCIs for device control (with no stimulation capacity),Footnote 20 neuroprediction systems,Footnote 21 and fMRI-based techniques.Footnote 22 Examples of type 2 include invasiveFootnote 23 and noninvasiveFootnote 24 brain stimulation, for example, to treat neurological or psychiatric disorders. An example of type 3 is closed-loop neuroadaptive brain stimulation via implants that monitor brain activity and deliver stimulation based on these measurements (thereby “closing the loop”) with the aim to modulate brain activity (e.g., in treating Parkinson’s disease).Footnote 25 While neurotechnologies today are mostly developed for use within individual brains, there are already proof-of-concept studies that demonstrate the possibility of brain-to-brain interaction mediated by neurotechnology.Footnote 26

Neurotechnologies and Human Rights: The Current State of the Legal Debate

The ethical and legal implications of neuroscience research, as well as the regulation and use of neurotechnologies, have received attention since the 1990s. This decade was often referred to as the “decade of the brain”Footnote 27 as it witnessed a substantial boost in funding for neuroscience and neurotechnology research. This trend was subsequently amplified by the later emergence of large-scale research projects such as the EU’s Human Brain Project and the US BRAIN Initiative in the 2000s and 2010s.Footnote 28 Since the inception of these large-scale projects, a crucial societal topic has been the legal protection of the human person against misuses of neurotechnology by governments or private actors (such as individual users, user groups, but also companies that develop and/or manufacture neurotechnological devices).

It is beyond question that a set of established human rights applies to many conceivable scenarios of neurotechnological use. They include the rights to bodily integrity, privacy, personal identity, freedom of thought, and autonomy. However, a need for a widening of existing rights has been examined through discussions of the idea of “cognitive liberty” since the turn of the millennium.Footnote 29 This debate has recently received renewed interest under the heading of “neurorights,” an umbrella term used to encompass the set of rights that should guarantee adequate protection of the mind and brain of the human person. Although the terminology sometimes diverges, three neurorights families appear central to the present debate: a right to mental privacy, a right to mental integrity, and a right to cognitive liberty.Footnote 30

From the current debate, it seems that legal protection of the mind might be pursued in the following ways: (1) under international and supranational human rights law,Footnote 31 (2) under domestic constitutions, (3) under ordinary domestic laws (including, e.g., applied areas such as consumer protection law), and (4) by some combinations of 1, 2, 3 in a multilevel legal approach or framework. As previously mentioned, this paper focuses on human rights at the level of international and supranational law.

In the discussion on human rights protection of the brain and mind, three main positions can be distinguished.

1. Novel rights for specifically protecting the brain and mind (“neurorights”) are necessary. According to this position, the scope of protection of existing rights and freedoms is insufficient to offer adequate legal protection from misuse of emerging neurotechnologies. At the time these rights were introduced, no one could have foreseen the possibilities neurotechnology offers today to monitor and intervene in our brains and, ultimately, in our mental states and behaviors. Hence, in the development of existing rights, the intricacies of game-changing neurotechnologies have not been considered. Even though it might be possible to broaden their protective scope during their application, ultimately, by court decisions, new neurorights must be introduced in order to fill the current gap in legal protection in a swift manner.Footnote 32

2. Adaptive interpretations and applications of existing rights are necessary, but novel neurorights are not. Scholars defending this position agree with advocates of position 1 that the scope of protection offered by established rights and freedoms is insufficient to offer adequate protection with respect to emerging neurotechnologies. However, instead of advocating the introduction of novel rights and freedoms, they hold that it would be sufficient to update our interpretations of existing human rights.Footnote 33 Ultimately, the precise level of legal protection will depend on how we specify the protective scope of existing rights through interpretation and application and what kind of positive obligations can be derived from them for state actors to ensure their enjoyment in the context of emerging neurotechnologies. Current rights that are prima facie well positioned to ensure legal protections for minds and brains include the right to privacy, the right to freedom of thought, and the right to mental integrity. Apart from human rights, derived (individual-subjective) rights should be taken into account as well, such as those defined on the national or supranational level by the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in the European legal context.Footnote 34

3. No novel rights, reforms, or new interpretations are necessary. The third position argues that the existing human rights suffice to offer effective legal protection from the misuse of emerging neurotechnologies. Therefore, both novel rights and evolutionary interpretations of existing rights are unnecessary. This type of argument, as of now, is not very prevalent in the current academic literature on the topic, but, in the experience of the authors, is often invoked in discussions in legal and policy fora on neurorights.Footnote 35

In discussing these positions, much emphasis is given to contingent technological considerations of the current capabilities of neurotechnologies to enable inferences on internal mental states from brain measurements, or to interfere with brains and mental states. However, regardless of the contingent state of neurotechnology at any given time, the analytic question of whether we should develop specific protections for the brain and mind has critical importance.Footnote 36 Comparing and critically evaluating the various normative and conceptual stances at a high level are essential to advance the debate on “neurorights,” identify both conceptual divergences and areas of common ground, as well as provide policymakers with a conceptually solid foundation for present and future policy work in this area.

Interdisciplinary discussions on neurorights require clarity about rights. Moral values are often couched in the language of rights, since rights have become a key currency in which societal conflicts are addressed and resolved. But many do not demand legal rights in a strict sense. Rather, the ethical debate around neurorights wishes to affirm moral interests or values, and many derive claims for stronger legal protection from these ethical considerations. It is important to bear in mind that legal rights are not merely the legal variations of moral claims or interests. They are technical entities interwoven with the legal frameworks in which they are embedded and interrelated to other rights and norms.Footnote 37

A further important point about legal rightsFootnote 38 is that they can be situated at different levels: in regulations or statutes of ordinary positive law or in constitutional or even international law. At these levels, legal rights are abstract and general, albeit to varying degrees, and apply to innumerable situations. Because of this, they often have to be more precisely defined by the law and courts so that they can be applied in specific cases. In addition, rights at the latter two levels have been argued to be either more or less powerful than rights at the former levels. It should be noted, however, that it seems debatable how powerful international rights are because in many countries international law generally has no effect in the courts unless a parliament has chosen to give effect to it through legislation.

In this paper, we will not take a position about the need for specific neurorights to protect the core subject matter identified in Section “Conceptual and ethical foundations of mental integrity, mental privacy, and cognitive liberty.” Rather, we aim to advance the debate by considering the extent to which mental integrity, mental privacy, and cognitive liberty enjoy protection under the established framework of human rights law (Section “Legal foundations of mental integrity, mental privacy, and cognitive liberty”). This systematic analysis based on the normative foundations discussed in Section “Conceptual and ethical foundations of mental integrity, mental privacy, and cognitive liberty” will be relevant to all three central positions regarding the development of specific neurorights on the international and regional levels.

Conceptual and Ethical Foundations of Mental Integrity, Mental Privacy, and Cognitive Liberty

We recognize three core families of ethical and legal entitlements that can be construed as so-called neurorights. These are mental integrity, mental privacy, and cognitive liberty. It should be noted that whereas mental integrity and mental privacy have been established as predominantly negative rights, as they are meant to ensure a freedom from external coercion or interference with agents’ brains and minds, cognitive liberty, however, has been interpreted more broadly to include both negative freedom from coercion or interference and positive freedom to control one’s own brain and mind.

Mental Integrity

Conceptually, mental integrity can be understood as an analog of the better-understood and more widely recognized notion of bodily integrity. From a moral perspective, in a minimalist conception, the right to bodily integrity protects against certain forms of interference with one’s body. By analogy, the right to mental integrity, on a minimalist conception, would protect against certain forms of interference with one’s mind.

We suggest that a moral right to mental integrity can coherently be endorsed and distinguished from a moral right to bodily integrity, even if the mind is merely part of, or wholly resides in, the body. On these views, the right to mental integrity could be understood as a right over certain parts or functions of the body, that is, the brain.Footnote 39

As well as mirroring the right to bodily integrity in its content, the right to mental integrity might be thought to share its justification with the right to bodily integrity. The right to bodily integrity is often thought to be grounded in rights of self-ownership or personal sovereignty.Footnote 40 Since the mind is enabled by the body (the central nervous system, in particular) and the self and personhood are functions of the mind, it is plausible that if self-ownership and personal sovereignty ground a right to bodily integrity, they also ground a right to mental integrity.Footnote 41

Some might argue, given that the mind is part of and enabled by the body, and that the body already enjoys the established protection of an integrity right, a right to mental integrity would be superfluous. However, this objection does not consider that the kinds of bodily interference that infringe the right to bodily integrity do not necessarily correspond to the kinds of mental interference that infringe a right to mental integrity. Consider, for example, so-called “non-invasive” brain stimulation (NIBS), such as transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) and transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), which stimulate the brain via electrodes or electromagnets placed on the scalp. Nonconsensual NIBS could amount to a severe mental interference, and thus a serious violation of the right to mental integrity, even though, given the absence of significant changes in brain anatomy, they arguably might involve no or little interference with the body.

The idea of a right to mental integrity raises several questions. For example, which kinds of mental influence qualify as mental interference, and which mental interferences precisely infringe upon the right to mental integrity? Does the interference have to be harmful, for example, or at least significant in its effects? Given that in social dynamics every actor constantly influences other actors—including at the level of beliefs, desires, and feelings—the right to mental integrity threatens to be very expansive. Therefore, it would need to be specified in such a way that distinguishes violations of mental integrity from innocuous and inevitable forms of mental influence, such as bona fide argument-based persuasion.Footnote 42

Mental Privacy

Mental privacy has long been considered an important feature of human individuality and freedom. Several features of mental privacy can be distinguished.Footnote 43 Mental states can be incommunicable or inaccessible to others in the sense that people can experience insurmountable difficulties in adequately expressing their thoughts or feelings. That is, there can be a felt difference between the report and the experience of that which is reported, in part due to the special access one has to one’s own inner life. Mental states can also be taken to be unchallengeable. “That’s how I feel it” is a statement that in many cases invokes an unassailable authority regarding the knowledge about one’s mental life from the first-person perspective. Therefore, the potential implications of brain reading for a person’s privacy and authority regarding their mental life are substantial.

First, the possibility that thoughts and feelings could be observed indirectly not only through behavior but also through multimodal data analysis in which data about brain states play a substantial role may have significant consequences for the individual, their social interactions, and political freedoms. Privacy as “the right to be let alone”Footnote 44 can be considered an important precondition for human freedom and dignity.Footnote 45 The decoding of brain data may one day reveal mental information such as someone’s sexual preferences and political orientation, potentially leading to discrimination and prejudicial treatment. Knowing a person’s preferences and emotions (e.g., fears) could enable another actor to control that person’s behavior.Footnote 46 Obviously, human rights law recognizes a right to respect for private life, the protection of personal data, the right to freedom of thought, and the freedom to hold opinions. However, one could argue that there are important aspects regarding the relation of the right to mental privacy and the freedom of thought that need to be considered from an ethical and legal perspective; for example, having free thoughts that are nevertheless monitored continuously could be seen as a violation of mental privacy under certain circumstances (e.g., in the absence of ongoing consent).

On the positive side, the possibility of effectively “reading” the mind would be of paramount importance in aiding patients who, for whatever reason, may have lost their capacity to communicate and/or move (e.g., patients with severe motor impairment or disorders of consciousnessFootnote 47) as well as helping them to protect their own rights. For example, such technology can be used to allow people with communication disabilities to express their voluntary and informed consent.Footnote 48 Similarly, it can help people with physical disabilities or psychological problems to allow themselves to be helped.Footnote 49 In cases where someone’s self-understanding or self-control diminishes or is failing, accessing their brain states and making them available to the person in question through processes of neurofeedbackFootnote 50 may lead to behavioral and cognitive improvements.

Second, being able to access the neural bases of mental states implies that one can evaluate the veracity of an individual’s reports. This may have important consequences in legal contexts, for example, in criminal law concerning the truthfulness of suspects’ or witnesses’ statements (lie detection, brain fingerprinting).Footnote 51

Third, by examining an individual’s brain, it is possible to attempt to override and correct their reports about thoughts and feelings. One could advocate (or contest), for instance, the use of brain reading in tort law for an objective assessment of the validity of claims about damage (e.g., pain) resulting from an incident.Footnote 52 In a psychotherapeutic context, one can also consider utilizing the more profound knowledge of brain states to aid patients.Footnote 53

When considering mental privacy in the face of neurotechnologies, it is useful to make some clarifications with respect to the different levels at which interference with the personal sphere of the individual can occur. This allows us to better qualify the kind, content, and ranking of rights that are relevant to potential violations of mental privacy.

It is often claimed that a great deal of personal information is disseminated by individuals either voluntarily (e.g., through social media interactions) or unintentionally, through the many electronic tracking and logging systems that we implicitly or explicitly consent to, are unaware of, or do not care about at all. However, it appears that it is difficult to propose a rigid application of mental privacy in a context in which information circulates in large quantities and at great speed. The type of information that can be collected, thanks to digital profiling (either lawfully or unlawfully), makes it possible to track, analyze, and predict many attitudes and behaviors of individuals, even those that are more sensitive and relating to sexual orientation, political leaning, or health status.

It can therefore be inferred that the information residing in an individual’s mind and brain is potentially more sensitive and subjectively relevant to them compared to non-mental information, as it is otherwise inaccessible to others. The mind and the brain are thus, even in comparison with the difficulty in keeping other data confidential, the ultimate seats of personal information and the individual’s refuge of privacy, to which special protection is to be attributed.

Cognitive Liberty

If the right to mental privacy may help protect the mind from external access and inspection, the principle of cognitive liberty has been invoked to protect mental states from external influence and interference. This human right candidate has been defined as a person’s autonomous, unhindered control or mastery over their mind. For example, Bublitz has described cognitive liberty as a synonym for “mental self-determination.”Footnote 54 In his account, this right comprises, among others, two fundamental and intimately related principles: (1) the right of individuals to freely use emerging neurotechnologies and (2) the protection of individuals from coercive or unconsented use of such technologies. In other words, cognitive liberty is a principle that guarantees “the right to alter one’s mental states with the help of neurotools as well as to refuse to do so.”Footnote 55 A similar account is provided by Farahany, who defines cognitive liberty as “the right to self-determination over our brains and mental experiences.”Footnote 56 She advances cognitive liberty as an updated concept of liberty for the digital age, rather than as a neurorights concept limited to neurotechnologies. In this view, the right to cognitive liberty encompasses a broad spectrum of freedoms and rights such as the “freedom of thought and rumination, the right to self-access and self-alteration, and to consent to or refuse changes to our brains and our mental experiences” (p. 98). In Farahany’s view, the right to cognitive liberty “is not absolute, but must be balanced against the societal costs it introduces.” Ienca and Andorno have also recognized the dual nature of cognitive liberty by arguing that it constitutes a “complex right which involves the prerequisites of both negative and positive liberties in the sense of Isaiah Berlin” (Berlin, 1969).Footnote 57 In its negative sense, cognitive liberty describes making choices about one’s own cognitive domain in the absence of external obstacles, barriers, or prohibitions, as well as exercising one’s own right to mental integrity in the absence of external constraints or violations. In its positive sense, it involves the capability and right of acting in such a way as to take control of one’s mental life. They also acknowledge the non-absolute nature of this right.

Many authors have emphasized the conceptual proximity between cognitive liberty and the right to freedom of thought. Some of them, such as Lavazza,Footnote 58 have argued that the existing right to freedom of thought is normatively well suited to address all human rights challenges raised by neurotechnology and other emerging technologies. Other authors, such as Ienca,Footnote 59 have argued that the primary scope of the right to freedom of thought did not concern cognitive and affective processes (forum internum). In contrast, it concerned societally embedded entitlements such as the freedom of conscience and religion. According to this view, although cognitive liberty and freedom of thought are intimately intertwined, they are better understood as distinct rights. Similarly, Farahany has argued that cognitive liberty is broader than the freedom of thought because it also includes the right to self-determination (self-access and self-alteration), the right to consent to or refuse changes to our brains and mental experiences, and the right to mental privacy as three overlapping but necessary components to cognitive liberty.Footnote 60

Legal Foundations of Mental Integrity, Mental Privacy, and Cognitive Liberty

It should be noted that the three notions described above are not to be seen as standalone normative principles. For example, to influence someone’s mental states, it is necessary to have access to their mental information in the first place. In those cases, both mental privacy and cognitive liberty are inevitably at stake. Similarly, unauthorized modification of a person’s mental state may qualify as a violation not only of cognitive liberty but also of mental integrity. Therefore, the triadic classification above should be seen as purely taxonomical, not as indicative of (an absence of) relational dynamics.

Taxonomic considerations aside, one crucial question is how the protection of mental integrity, mental privacy, and cognitive liberty could be anchored in established human rights. Therefore, in the next section, we will attempt to point to legal foundations of these prima facie rights and map their relationship to established human rights. Generally, we will take the right to mental integrity to refer to the protection from certain forms of unwanted or unwarranted interference with one’s mind, the right to mental privacy to the protection against certain forms of access to one’s mind, and the right to cognitive liberty to the protection of one’s mental self-determination.

The Right to Mental Integrity

Presently, a right to mental integrity has been recognized under different international and regional human rights instruments. At the international level, neither the UDHR nor the ICCPR guarantees an explicit right to mental integrity. However, Article 17 of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) prescribes that “every person with disabilities has a right to respect for his or her physical and mental integrity on an equal basis with others.”

Within the inter-American context, Article 5(1) of the ACHR states that “every person has the right to have his physical, mental, and moral integrity respected.” The different dimensions of integrity described by Article 5 ACHR are associated with health, understood in a wide sense that encompasses complete physical, mental, and social well-being. However, in the Declaration of the Interamerican Juridical Committee on Neuroscience, Neurotechnologies, and Human Rights, some worries have been raised about the scope of this right. Although the enforceable contents of the right are clear within the medical context (e.g., the right to informed consent and to medical confidentiality), they are less clear for neurotechnologies with nonmedical purposes.Footnote 61

In the European context, the right to mental integrity has been recognized in the jurisprudence of the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR), alongside the right to bodily integrity. Both are part of the right to respect for private life, guaranteed by Article 8 of the ECHR.Footnote 62 Sometimes, the ECtHR also refers to the right to “moral” and “psychological” integrity, but the case law suggests that mental, psychological, and moral integrity are interchangeable terms.Footnote 63 The recognition of the right to mental integrity by the ECtHR is also reflected in the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union (CFR), aiming to provide comprehensive protection of the person, especially against novel technologies.Footnote 64 According to Article 3(1) CFR, “everyone has the right to respect for his or her physical and mental integrity.”

Although the right to mental integrity has an explicit basis in established human rights law, the exact scope and limits of this right have not yet been clarified.Footnote 65 Accordingly, its implications with respect to neurotechnology are still unclear.Footnote 66 Meanwhile, in the European context, some contours of the right to mental integrity have been sketched. This could provide helpful directions in the debate about neurotechnology and mental integrity. For example, case law on Article 8 ECHR illustrates that mental health is to be considered a crucial part of private life associated with mental integrity.Footnote 67 Furthermore, the right to mental integrity appears to cover complaints about bullying at school,Footnote 68 well-founded fear of physical abuse,Footnote 69 and loss of honor and reputation.Footnote 70 In addition, the ECtHR considers that, together with the notion of physical integrity, a person’s mental integrity embraces multiple aspects of their identity, such as gender identification, sexual orientation, name, and elements relating to their right to be imaged.Footnote 71

Furthermore, the EU Network of Independent Experts on Fundamental Rights, set up by the European Commission, considers that the right to mental integrity pursuant to Article 3(1) CFR “is a fairly broad right.”Footnote 72 It not only includes the prohibition of mental torture, inhuman and degrading treatment, and punishment but also covers a broad range of less serious forms of interference with a person’s mind, which have traditionally been covered by the right to privacy. Examples concern mandatory treatment with psychoactive drugs, forced psychiatric interventions, strong noise, and “brainwashing.”Footnote 73 Interferences with the mind through neurotechnology may well fit within this series of mind-altering interventions that are covered by the right to mental integrity in the meaning of Article 3 CFR.

Interestingly, apart from the right to mental integrity, changing people’s minds (without consent) through means such as brainwashing is covered by the existing right to freedom of thought as well, at least to some extent.Footnote 74 The inner part of this right—the freedom to have, adopt, and change thoughts, conscience, and religion—seeks at its most basic level “to prevent state indoctrination of individuals by permitting the holding, development, and refinement and ultimately change of personal thought, conscience and religion.”Footnote 75 This internal dimension of freedom of thought is absolute. It protects the freedom of thought unconditionally.Footnote 76 The scope of the right to freedom of thought is considered to be broad, as it not only covers the protection of religious thoughts and convictions.Footnote 77 In addition, it pertains to the freedom of thought “on all matters,” encompassing a whole range of personal and collective convictions in the political, economic, social, scientific, and intellectual spheres.Footnote 78

Meanwhile, the exact scope of the right to freedom of thought is as yet unclear. Some have defended a broad scope so as to cover a wide range of neurotechnologies that affect mental properties such as thoughts, memories, and, possibly, emotions.Footnote 79 Others have suggested a somewhat restricted understanding,Footnote 80 which might not cover just any mind-altering technique and would thus arguably put more emphasis on the right to mental integrity to protect against unwanted mental interference.Footnote 81 How exactly the qualified right to mental integrity relates to the absolute right to freedom of thought is however an open question.Footnote 82

The Right to Mental Privacy

Unlike the right to mental integrity, the right to mental privacy has not yet been recognized as a specific human right, at least not explicitly. However, the privacy of our thoughts, emotions, and other mental states seems to gain at least some implicit legal protection under three distinctive human rights and freedoms. These are (1) the right to privacy, (2) the right to freedom of thought, and (3) the right to freedom of expression. Mental privacy as a specific right vis-à-vis neurotechnology is characterized differently by its kind and content and, consequently, is a potential candidate for a right with an especially high priority. This is justified by the fact that the tools capable of brain reading can access personal information (thoughts, judgments, desires, intentions) an individual has never or could never manifest externally.Footnote 83 This can actually happen today, for instance, with communication neurotechnology based on detecting and interpreting neural signals to produce intelligible speech, writing, or typing.Footnote 84 Let us consider current human rights protection of mental privacy in some more detail below.

The right to privacy

Article 12 UDHR prescribes that “no one shall be subjected to arbitrary interference with his privacy, family, home or correspondence, nor to attacks upon his honor and reputation. Everyone has the right to the protection of the law against such interference or attacks.” A similar right is guaranteed by Article 17 ICCPR. According to the UN Human Rights Council (HRC), privacy presumes that individuals should have an area of autonomous development, interaction, and liberty. People should have a “private sphere” with or without interaction with others, free from state intervention as well as excessive unsolicited interventions from other uninvited individuals.Footnote 85 Article 17 ICCPR pertains to all interferences with a person’s privacy, regardless of whether they emerge from state officials or natural or legal persons. States must adopt legislative and other measures to give effect to the prohibition against privacy interferences under Article 17 ICCPR.Footnote 86 In the age of technology and digital environments, the HRC considers informational privacy of particular importance, covering information about a person or her life and decisions based on that information.Footnote 87

The scope of the international human right to privacy is broad and able to adapt to modern means of privacy interference, such as through neurotechnology. For example, it already covers the protection of metadata, as such data, when analyzed and aggregated, “may give an insight into an individual’s behavior, social relationship, private preference and identity.”Footnote 88 Furthermore, the HRC refers to data-driven technologies, which “increasingly enable States and business enterprises to obtain fine-grained information about people’s lives, make inferences about their physical and mental characteristics and create detailed personality profiles.”Footnote 89

Within the inter-American context, Article 11 of the ACHR recognizes the right to privacy. Mirroring the UDHR and the ICCPR, it articulates the right to protection from arbitrary or abusive interferences with private life and unlawful attacks on honor or reputation. Interestingly, a detailed account of informational privacy has also been provided by the Inter-American Juridical Committee (CJI). The 2021 Updated Principles of the Inter-American Juridical Committee on Privacy and Personal Data Protection present a specific set of rules for data protection. These include transparency, consent, justification of the relevance and necessity of data processing, the restriction of data retention and processing, data confidentiality, security and accuracy, and the facilitation to data owners of access, rectification, erasure, and portability of data. Regarding mental privacy, it is worth mentioning the definition of sensitive personal data provided by these Updated Principles, which affirm that some types of personal data “are especially likely to cause material harm to individuals if misused [and] [d]ata controllers should adopt reinforced privacy and security measures that are commensurate with the sensitivity of the data and its capacity to harm the data subjects.”

The recent Declaration of the Inter-American Juridical Committee on Neuroscience, Neurotechnologies, and Human Rights specifically refers to this principle in its justification of the idea that neural data protection may require updating traditional formulas for the protection of privacy in other to prevent different ways in which its collection, processing, and application could affect the autonomy and personality of individuals.

The Declaration suggests that the special protection required by neural data is grounded in how the revelation of such data could affect a person’s identity and autonomy, highlighting that neural data could be used to manipulate mental processes and, ultimately, behavior: the “development of neurotechnologies can lead to the conditioning of personality and the loss of autonomy of individuals, and in this context one of the most pressing concerns has to do with the malicious behavior of those who access the people’s brain activity data in order to penetrate their minds, condition them, or take advantage of such knowledge.”

In the European context, the right to respect for private life has been recognized by Article 8 ECHR. When interpreting this right, the ECtHR considers the notion of personal autonomy as an important principle.Footnote 90 It argues that the protection of personal data is of fundamental importance to the enjoyment of the right to respect for private life pursuant to Article 8 ECHR. Accordingly, the domestic laws “must afford appropriate safeguards to prevent any such use of personal data as may be inconsistent with the guarantees of this provision. Article 8 ECHR thus provides for the right to a form of informational self-determination, allowing individuals to rely on their right to privacy as regards data which, albeit neutral, are collected, processed and disseminated collectively and in such a form or manner that their Article 8 rights may be engaged.”Footnote 91 In considering whether personal data relate to “private life” in the meaning of Article 8 ECHR, and whether the collection, storage, or use of that information will infringe this right, the ECtHR takes account of the specific context in which the data have been recorded and retained, the nature of the data, the way in which they are used and processed, the results that may be obtained, and, sometimes, the reasonable expectations of a person’s privacy.Footnote 92

Similar to the ICCPR, Article 8 ECHR has the ability to adapt to current developments in society, including developments in technology and bioethics.Footnote 93 Furthermore, in the European context, Article 7 CFR guarantees the right to respect for one’s private life, and Article 8 CFR covers the protection of personal data, discussed in much detail in the GDPR of EU secondary law. In this regard, personal data have been defined as “information relating to an identified or identifiable natural person (‘data subject’); an identifiable natural person is one who can be identified, directly or indirectly, in particular by reference to an identifier such as a name, an identification number, location data, an online identifier or to one or more factors specific to the physical, physiological, genetic, mental, economic, cultural or social identity of that natural person.”Footnote 94

In sum, it is clear that people’s privacy and, more specifically, their personal data deserve considerable legal protection. It is also clear that brain-derived data will, in most cases, qualify as protected “personal data,” as they often relate to an identified or identifiable individual.Footnote 95

The right to freedom of thought

Another human right of relevance to the protection of mental privacy is the right to freedom of thought (briefly discussed in Section “The right to mental integrity”).Footnote 96 The absolute, inner part of this right guarantees, amongst other things, that no one can be compelled to reveal one’s thoughts or adherence to a religion.Footnote 97 According to the UN Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Religion or Belief, this implies that mental privacy “is a core attribute of freedom of thought. The right not to reveal one’s thoughts against one’s will arguably includes ‘the right to remain silent,’ without explaining such silence.”Footnote 98

Similar to the right to privacy, it is clear that established human rights law guarantees robust legal protection to the freedom of thought. Meanwhile, the extent to which the right to freedom of thought protects brain-derived data that enable drawing inferences about a variety of mental properties is yet an open question. Much of the answer to this question will depend on how one understands the right to freedom of thought, having either a broad or a narrow scope.Footnote 99 A further question would be how the protection of mental privacy through the absolute right to freedom of thought would relate to the typically qualified protection of privacy rights, allowing for exceptions in certain situations. If mental privacy would be covered by both rights, there is a need to develop a theory that clarifies when information about the mind deserves absolute legal protection of the right to freedom of thought, over and above the qualified protection of the general right to privacy.Footnote 100

The right to freedom of expression

Interestingly, Article 13 ACHR assures the right to freedom of thought in conjunction with the freedom of expression: “Everyone has the right to freedom of thought and expression. This right includes freedom to seek, receive, and impart information and ideas of all kinds, regardless of frontiers, either orally, in writing, in print, in the form of art, or through any other medium of one’s choice.” Although formulations and levels of legal protection vary across different human rights instruments, the freedom of expression receives considerable protection under established human rights law, inter alia by Article 19 ICCPR, Article 13 ACHR, Article 10 ECHR, and Article 11 CFR. The scope of this right is conceived to be “extremely broad.”Footnote 101 It extends to all forms of expression that impart or convey opinions, ideas, or information of any kind. Moreover, it not only protects the substance of ideas and information that are expressed but also covers the means by which they are manifested, transmitted, and received, ranging from speech, sign language, and nonverbal expression through images and objects, to film, radio, and internet-based modes of expression.Footnote 102

The relevance of the freedom of expression to the protection of mental privacy lies in the fact that this freedom implies a negative aspect—a freedom not to express oneself. As one general comment to Article 19 ICCPR puts it: “Freedom to express one’s opinion necessarily includes freedom not to express one’s opinion.”Footnote 103 Regarding Article 10 ECHR, Harris et al. signal that “albeit sparse in the case law, Article 10 guarantees to some extent the negative aspect of freedom of expression, namely the right not to be compelled to express oneself. One notable example is the right to remain silent.”Footnote 104

This negative freedom has the potential to embrace the liberty not to express or transmit by any—such as through BCIs or other neurotechnologies—brain-related information that enables the drawing of inferences about a variety of mental states, irrespective of their content.Footnote 105 However, both in theory and in practice, the freedom of nonexpression has only received little attention so far. Although it seems clear that the scope of this right is broad, its exact meaning and normative implications are to a large extent unexplored. This lack of well-defined doctrine entails uncertainties regarding the exact kind and level of legal protection the right to freedom of nonexpression would offer to the notion of mental privacy. At the same time, the undeveloped nature of the freedom of nonexpression can also offer opportunities. The precise scope and implications of this right are yet to be defined, as are the weight and importance of all kinds of competing interests in the balancing of this right. In developing a legal doctrine on the freedom of nonexpression, scholars, judges, legislators, and policymakers can take into account the particularities neurotechnologies raise to the personal interest of mental privacy.Footnote 106

To summarize, the notion of mental privacy receives some protection in the established systems of human rights, most notably by the right to privacy, the right to freedom of expression, and the right to freedom of thought. Thus, the general framework to protect mental privacy is provided by established human rights. Now there is a need to specify this framework and clarify how the different rights within that framework complement and relate to each other.

The Right to Cognitive Liberty

At present, the legal protection of cognitive liberty has no explicit basis in established human rights law. However, it has been argued that the right to cognitive liberty could be seen as an extension or conceptual update of the existing right to freedom of thought (discussed in Sections “The right to mental integrity” and “The right to mental privacy”).Footnote 107 According to Farahany, cognitive liberty encompasses the freedom of thought and rumination, the right to self-access and self-alteration, and the freedom to either consent to or refuse changes to our brains and our mental experiences. These concepts make up the “bundle of rights” of cognitive liberty, which translate to human rights to freedom of thought, to self-determination, and to mental privacy. Farahany advocated cognitive liberty be recognized as a new human right, directing the updating of the three existing human rights the “bundle” implicates—the freedom of thought, the collective right to self-determination, and privacy.Footnote 108 She suggests cognitive liberty as a whole be balanced against other societal interests, while certain aspects of the bundle of rights, namely the freedom of thought, are absolute.

Sometimes, the right to cognitive liberty is also referred to as the right to “mental self-determination.”Footnote 109 That is, our control over our own mental lives—a right to self-determine what is in or on your mind. Regarding the European context, it seems plausible that the right to mental self-determination could receive increased support in the near future—not necessarily as an extension or update of the absolute freedom of thought, but possibly also as a specification of the qualified right to respect for private life.Footnote 110 For example, the Committee on Bioethics of the Council of Europe remarked in its Strategic Action Plan on Human Rights and Technologies in Biomedicine (2020–2025):

Technological developments in the field of biomedicine create new possibilities for intervention in individual behavior. For instance, certain technologies raise the prospect of increased understanding, monitoring, and control of the human brain, while other developments allow for the permanent health monitoring of individuals. These developments raise novel questions relating to autonomy, privacy, and even freedom of thought. … In the light of these developments, the third pillar of the Strategic Action Plan addresses concerns for physical and mental integrity. Guaranteeing respect for a person’s integrity in the sphere of biomedicine is one of the central tenets of the Oviedo Convention. This is understood as the ability of individuals to exercise control over what happens to them with regard to, inter alia, their body, their mental state, and the related personal data. Footnote 111

According to the committee, the notion of “mental integrity”—protected as part of private life under Article 8 ECHR—embraces the ability to control our own mental states. Within that approach, the right to mental integrity comes down to the freedom to exercise control over what is in or on our minds. In other words, in this conception, the right to mental integrity could comprise the right to mental self-determination and the right to cognitive liberty.Footnote 112

Whether the ECtHR would be inclined to follow a similar, broad interpretation of the right to respect for private life is an open question. To date, it has accepted “private life” to cover a right to mental integrity,Footnote 113 a generic right to self-determination,Footnote 114 as well as a specified right to informational self-determination. Footnote 115 Perhaps, an explicit recognition of the right to mental self-determination Footnote 116 may well fit within the court’s conception of the right to respect for private life under Article 8 ECHR.Footnote 117

Concluding Remarks

Advances in neurotechnology and AI are not only challenging traditional boundaries of our brains and mental lives, but they also challenge our traditional ways of thinking about human rights. More specifically, as our analysis has shown, there is an agreement that mental privacy, mental integrity, and cognitive liberty are discernible notions of morality that need to be considered in legal response to advances in neurotechnology. Both ethical and legal scholarship have highlighted the relevance of these concepts.

However, there are substantial differences in terms of how the philosophical and ethical foundations of these “neurorights” are understood by scholars within and across academic fields. Since these notions can be conceptualized differently in terms of their philosophical and ethical foundations, it is debatable to what extent it is desirable and necessary to translate and condense them into specific legal rights at the international level as well as to integrate them into the existing human rights system. Therefore, to facilitate international debates on human rights protection of the mind, the ethical and philosophical understandings of neurorights need to be at least made transparent and explicit and, ideally, be harmonized across different fields and perspectives.

To this end, our paper—a concerted interdisciplinary effort by scholars from a variety of academic fields—mapped the ethical and legal foundations of central neurorights. The minimalist conceptual understandings of the key notions provided here could, we hope, facilitate further discussion and help improve legal and policy initiatives in this area, which will in turn enable the implementation of legal protections not only at the international human rights level but also in regional or national contexts.

Acknowledgments

S.L. and G.M. are funded by the Dutch Research Council (NWO Vici grant VI.C.201.067). The work of P.K. was partly funded by a grant from the Klaus Tschira Foundation (grant no. 00.001.2019). A.W.P. is funded by Agencia Nacional de Investigación y Desarrollo, Chile (FONDECYT INICIACIÓN 11220327).

Competing Interest

The authors declare none.