Introduction

The grassland habitats of Canada and their associated arthropod faunas have been dramatically altered since European settlement in the late 1800s. With <1000 non-indigenous people before 1870, estimated numbers on the Prairies Ecozone increased to 57 000 by 1881 and 99 000 by 1891 (Willms et al. Reference Willms, Adams and McKenzie2011). The population reached 3.5 million by 1981 and surpassed 4.5 million by 2006 (Statistics Canada 2006). With the increase in population, there has been a concurrent decrease in native habitats with at least 87% of the 443 000 km2 of the region now converted to farmland (Coristine and Kerr Reference Coristine and Kerr2011). Additional sources of disturbance include urban sprawl, water impoundments, drainage of natural wetlands, plus resource extraction, and its supporting infrastructure. Lands used to graze cattle have been fragmented by pipelines, railways, and roads, which has increased the invasion of native plant communities by exotic species (Vujnovic et al. Reference Vujnovic, Wein and Dale2002; Desserud et al. Reference Desserud, Gates, Adams and Revel2010) and has altered animal communities. About half of Canadian farms (and 80% of the farmland) occur in the prairies (Sauchyn and Kulshreshtha Reference Sauchyn and Kulshreshtha2008). Given this concentrated activity in a region that represents only 5% of the land base of Canada, it is not surprising that many of the native plant and animal species associated with the once vast prairies of Canada are now threatened and endangered (Coristine and Kerr Reference Coristine and Kerr2011; Hall et al. Reference Hall, Catling and Lafontaine2011).

In 1979, the Biological Survey of Canada (BSC) initiated a project to collect and synthesise information on the native arthropod fauna of undisturbed grassland habitats before these habitats were forever lost (Danks Reference Danks2016, Reference Danks2017). Over nearly 40 years, the BSC has promoted research on grassland habitats through newsletters, special symposia, and BioBlitzes (field collecting trips to document regional faunas). These activities culminated in the publication of four volumes of the BSC’s Arthropods of Canadian Grasslands series (Shorthouse and Floate Reference Shorthouse and Floate2010; Floate Reference Floate2011b; Cárcamo and Giberson Reference Cárcamo and Giberson2014; Giberson and Cárcamo Reference Giberson and Cárcamo2014). This retrospective is provided to increase awareness of the grasslands project, record some of the “lessons learned”, identify knowledge gaps, and facilitate future progress on this initiative.

The Prairies Ecozone and its constituent ecoregions

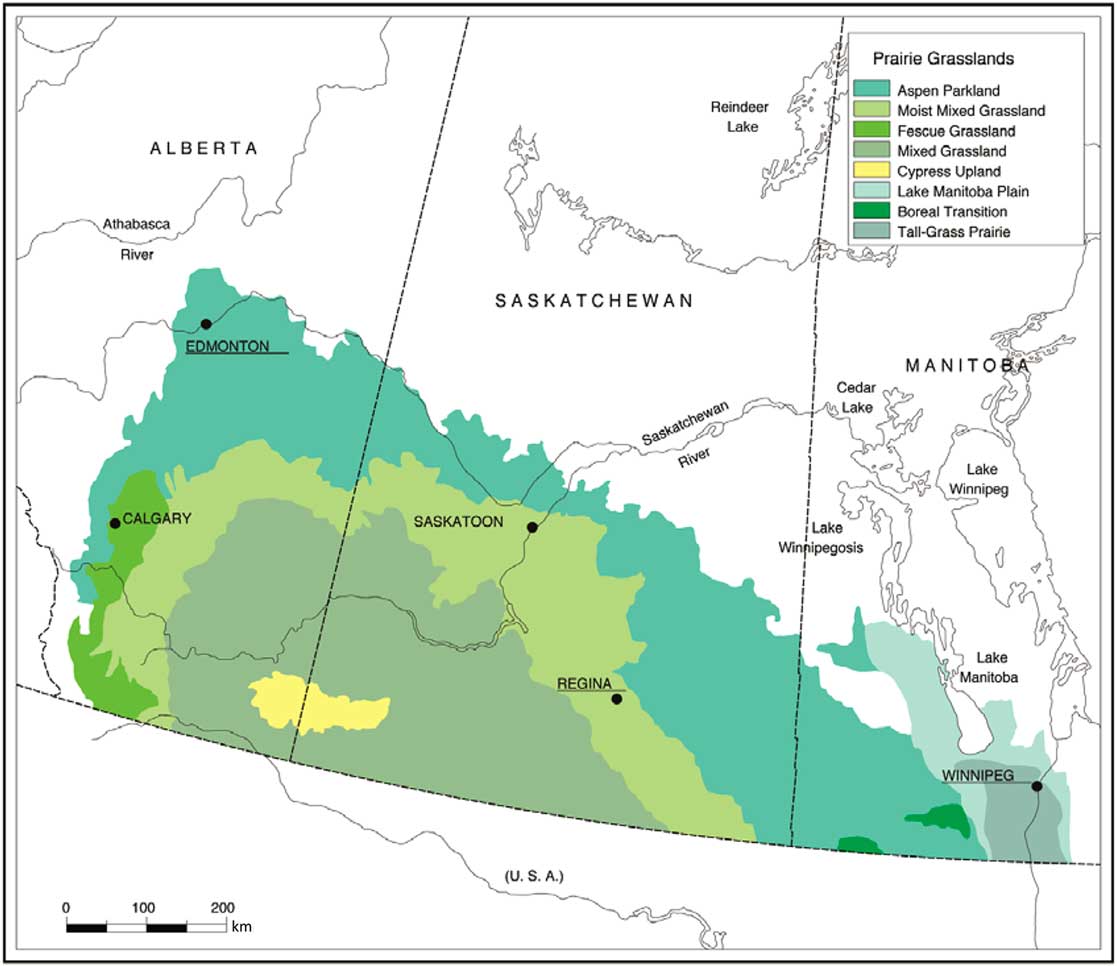

Grasslands are open expanses dominated by graminoids and forbs, where trees or shrubs comprise <10% of the ground cover (White Reference White1983). The grasslands of Canada occur mainly in the Prairies Ecozone, which encompasses the south-central portions of Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba, Canada; i.e., the Prairie Provinces (Fig. 1) (Shorthouse Reference Shorthouse2010b). This ecozone is the northernmost extension of the Great Plains of North America, which extends from the Rocky Mountains east to the Mississippi River in the United States of America and south into northern Mexico (Pieper Reference Pieper2005). Lesser and scattered expanses of Canadian grasslands occur in interior valleys of British Columbia and the Yukon, and in southern Ontario (Shorthouse Reference Shorthouse2010c).

Fig. 1 Map of Canada showing the location of ecoregions within the Prairies Ecozone. Reprinted with permission from Shorthouse (Reference Shorthouse2010b).

The Canadian Prairies Ecozone has a generally flat topography with a continental climate; i.e., long and cold winters with hot and short summers (Ecological Stratification Working Group 1995). The Rocky Mountains to the west deplete moisture-bearing air-masses from the Pacific Ocean resulting in a subhumid to semiarid climate. Climate change predictions are for increased aridity following greater numbers of dry years (Sauchyn and Kulshreshtha Reference Sauchyn and Kulshreshtha2008). An overview of the climate of the ecozone and climate change is provided by McGinn (Reference McGinn2010). A more recent summary of climate change for Canada is provided by Bush et al. (Reference Bush, Loder, James, Mortsch and Cohen2014). They report that average annual surface air temperature has increased by 1.5 °C from 1950 to 2010, with particularly strong trends during winter and spring seasons in the western part of the country. For example, mean maximum and mean minimum temperatures during spring on the prairies from 1950 to 1989 have increased by 3.8 °C and 2.8 °C, respectively (Skinner and Gullett Reference Skinner and Gullett1993). In combination with killing frosts occurring later in the fall, this has resulted in a general trend towards a longer growing season (Qian et al. Reference Qian, Zhang, Chen, Feng and O’Brien2010) with endemic species experiencing milder winters.

Climate change directly and indirectly affects arthropod populations, but studies of direct effects in the Canadian Prairies Ecozone have been largely limited to exotic species that are pests of crops (Olfert and Weiss Reference Olfert and Weiss2006; Olfert et al. Reference Olfert, Weiss and Kriticos2011, Reference Olfert, Weiss and Elliott2016). One probable impact is changes in the ranges of grassland species (Scudder Reference Scudder2010a), though these changes are not straightforward, since species of arthropod in Canadian grasslands are adapted to cold and dry winters, and are not just extensions of the fauna from grasslands further south (Scudder Reference Scudder2014b). Further, changes in the phenology of flowering plants may disrupt plant–pollinator interactions to the detriment of some species (Memmott et al. Reference Memmott, Craze, Waser and Price2007). An overview of climate change and its effects on biodiversity in Canada is provided by Coristine and Kerr (Reference Coristine and Kerr2011) and Nantel et al. (Reference Nantel, Pellatt, Keenleyside and Gray2014).

The Prairies Ecozone extends over a wide geographical area and shows considerable variation in major landforms, climate, soils, precipitation, vegetation, and human activity patterns/uses. This variation is captured by the separation of the ecozone into eight ecoregions: Aspen Parkland, Moist Mixed Grassland, Fescue Grassland, Mixed Grassland, Cypress Upland, Lake Manitoba Plain, Tall-Grass Prairie, and Boreal Transition (Fig. 1) (Ecological Stratification Working Group 1995).

Variation in annual precipitation in the Prairies Ecozone (which increases from west to east) also results in three types of prairie grassland, distinguished by the height of the dominant grass species: western shortgrass prairie (0.3–0.5 m height, 260–375 mm average annual precipitation), a central midgrass or mixedgrass prairie (0.8–1.2 m height, 375–625 mm), and an eastern tallgrass prairie (1.8–2.4 m height, 625–1200 mm) (Anderson Reference Anderson2006). Tall-grass prairie is the least protected type of grassland habitat with <1% remaining in an undisturbed state (Pearn and Hamel Reference Pearn and Hamel2014). More detailed synopses on features of the Prairies Ecozone and its ecoregions are provided in Shorthouse (Reference Shorthouse2010a, Reference Shorthouse2010b).

Arthropod diversity on the Canadian prairies

Danks (Reference Danks1979, Reference Danks1988) reported 34 000 known species of terrestrial arthropods in Canada, but estimated that ~66 000 species occur in the country, including ~54 000 insect species (~30 000 currently known), 11 000 species of arachnid (3000 known) and ~900 species of other terrestrial arthropods. Diverse groups thought to contain many undescribed or unrecorded species included Acari, Hemiptera, Coleoptera (especially Staphylinidae), Lepidoptera (especially Tineoidea), and particularly Diptera and Hymenoptera. The question of arthropod diversity in Canada was revisited by Hebert et al. (Reference Hebert, Ratnasingham, Zakharov, Telfer, Levesque-Beaudin and Milton2016), who used results of DNA barcoding to reassess these earlier estimates. They concluded that there may be more than 100 000 species of insects in Canada, including as many as 50 000 species of Diptera and 30 000 species of Hymenoptera. Similarly, Blagoev et al. (Reference Blagoev, deWaard, Ratnasingham, deWaard, Lu and Robertson2016) used DNA barcoding to conclude that the number of species of spiders in Canada (~1460) may be underestimated by 30–50%.

For the Canadian Prairies, early knowledge of arthropod diversity was spurred by the efforts of Edgar Strickland (1889–1962) (Hocking Reference Hocking1963; Byers and Cárcamo Reference Byers and Cárcamo2013) and Norman Criddle (1875–1933) (Holliday Reference Holliday2006). These two English immigrants are pioneers of entomology in Alberta and Manitoba, respectively. In 1913, Strickland founded the Dominion Entomological Laboratory in Lethbridge, Alberta, and Norman Criddle was appointed Entomological Field Officer in Manitoba. Their main activities focussed on finding ways to help farmers deal with serious pest outbreaks, including grasshoppers (Orthoptera: Acrididae), click beetles/wireworms (Coleoptera: Elateridae), and cutworms (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). However, they were both avid collectors and contributed significant knowledge on a wide array of arthropods that provided baseline data for future studies. Strickland produced checklists for click beetles, biting flies, parasitic wasps, Hemiptera, and leafhoppers (Hemiptera: Cicadellidae) and many other publications (Hocking Reference Hocking1963). Criddle published at least 65 articles with entomological content, with particular focus on the presence, ecology, and control of grasshoppers (Gibson and Crawford Reference Gibson and Crawford1933). He also contributed countless first records for the prairies. His systematic and thorough collecting near his home at Aweme in southwestern Manitoba has allowed for valuable historical analyses for selected taxa; e.g., Coleoptera: Carabidae (Holliday et al. Reference Holliday, Floate, Cárcamo, Pollock, Stjernberg and Roughley2014).

The Arthropods of Canadian grasslands initiative

The BSC was initiated in 1977 to “establish the basic inventory and natural history of the Canadian insect fauna, through collection and research on a comprehensive geographical scale and a publication programme for a series of identification and reference volumes” (Danks Reference Danks2016). The Arthropods of Canadian Grasslands was one of several BSC projects, each targeting a different region or habitat of the country. The Arthropods of Canadian Grasslands project officially started in 1979 with a focus on the faunas of undisturbed grasslands (this was later expanded to include disturbed areas as well) and the development of a network of arthropod workers interested in grassland habitats. A Grasslands Arthropods Newsletter was established to facilitate communication among researchers with 11 issues published; i.e., 1983–1990, 2000–2005 (http://biologicalsurvey.ca/pages/read/arthropods-of-canadian-grasslands-index). The publication gap between 1990 and 2000 was a period of lower interest in the project, which triggered a concerted effort to rejuvenate the project in 1999. The BSC organised a series of intensive collecting events (BioBlitzes) to various grassland sites; e.g., Onefour, Alberta, 2001; Dunvegan, Alberta, 2003, Aweme, Manitoba, 2004; Waterton Lakes National Park, Alberta, 2005; Riding Mountain National Park, Manitoba, 2007; Peace River Valley, British Columbia, 2015; and Carmacks, Yukon, 2016 (Danks Reference Danks2016). The objectives of the project were formalised in a grasslands “prospectus” in 2002, and formal symposia were held at national meetings of the Entomological Society of Canada (2002, 2010). Results of this activity have been published by the BSC in a monograph series titled Arthropods of Canadian Grasslands. Four volumes (totalling 1621 pages) have been published thus far (Shorthouse and Floate Reference Shorthouse and Floate2010; Floate Reference Floate2011b; Cárcamo and Giberson Reference Cárcamo and Giberson2014; Giberson and Cárcamo Reference Giberson and Cárcamo2014).

Several challenges were overcome to produce the monograph series. Potential contributors voiced different concerns regarding the scope and content of submissions. Some taxonomists felt the need for more study before undertaking a grasslands review, ecologists felt excluded from what they perceived to be primarily a taxonomic project, and applied entomologists felt a focus on undisturbed grasslands was too narrow. Thus, the objectives of the Arthropods of Canadian Grasslands project were expanded while maintaining its underlying objectives; i.e., to increase awareness of the vanishing grasslands in Canada and their associated arthropods, and to provide baseline references for future studies of arthropods in these habitats. As a result, submissions highlighting arthropod ecology, different habitats (including agroecosystems), specific grassland sites, species summaries and species checklists were all encouraged. Contributors also were encouraged to target a broad audience, including teachers, farmers, ranchers, naturalists, and researchers interested in the Prairies Ecozone. To make the products more attractive to this audience, contributors were encouraged to make liberal use of colour photographs, maps, images, and easily understood summary tables. The use of colour images was made practical by advances in print technology over the period that the BSC has been operating, which dramatically reduced the cost of colour plates.

The format in which the books were published was affected by recent advances in publishing, since the books could be produced (including professional copy-editing and page layout) as high-quality PDF files made available on the BSC website for free download (http://biologicalsurvey.ca/monographs/read/17). This reduced costs by eliminating the need to print and store quantities of books. Authors and other grassland workers pushed strongly for availability of hard-copy books, leading to the decision by the not-for-profit BSC to provide the option of hard-copy publication through a “print-on-demand” service. To reduce costs for the authors, page charges were at least partially subsidised by the BSC’s publishing arm for authors with limited funds. This hybrid model of free PDFs with the option to purchase print copies has since been adopted for other BSC monographs (e.g., Lindquist et al. Reference Lindquist, Galloway, Artsob, Lindsay, Drebot, Wood and Robbins2016).

The books cover an extensive array of topics relating to grassland arthropods. The first volume provides a general description of the biological and climatic aspects of the Prairies Ecozone and broad ecological factors that influence diversity of arthropods and their life histories (Shorthouse and Floate Reference Shorthouse and Floate2010). Topics in specific chapters range from summaries of arthropods from specific habitat types (e.g., soils, rose or cottonwood galls, tallgrass prairie) or taxonomic groups. The second volume is an examination of the arthropod fauna in modified habitats of the Prairies Ecozone, almost all of which has been converted into agroecosystems (Floate Reference Floate2011b). Topics begin with a review of the effects of European settlement on the habitat, then cover arthropod relationships (species patterns, species at risk, control strategies, and habitats such as ponds and streams, crops, livestock systems, and stored grains). The most recent two volumes (Cárcamo and Giberson Reference Cárcamo and Giberson2014; Giberson and Cárcamo Reference Giberson and Cárcamo2014) provide checklists and ecological, distributional/biogeographical, and/or habitat information for 24 higher level taxa (from family to class) represented in the Prairies Ecozone. These are in addition to the five species lists or summaries published in volumes 1 and 2 (see Table 1 for a summary of species diversity information from these books).

Table 1 Arthropod diversity recorded for the Prairies Ecozone of Canada (or for the Prairie Provinces – bold font).

Note: Unless otherwise stated, the information was taken from the publications of the Biological Survey of Canada as given in the reference column.

The success of the Arthropods of Canadian Grasslands initiative can be partially assessed by awareness of the grassland publications among the target audience; i.e., students, researchers, and the general public. Awareness was initially examined using Google with individual searches performed by chapter title on 26–28 March 2017. A total of 602 results were identified, spanning a wide range of sources; e.g., personal webpages, online industry magazines, online identification guides, and sources more specifically academic in nature.

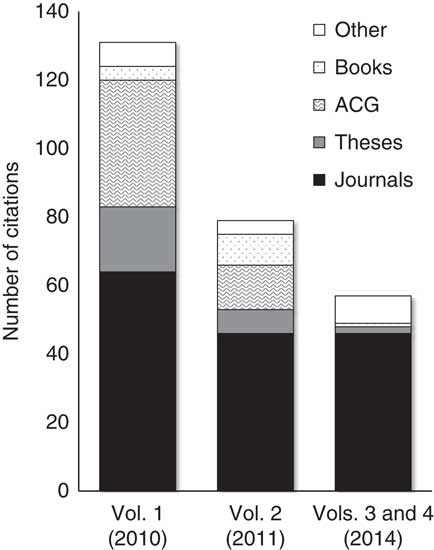

To assess more precisely the uptake of these chapters by the academic community, we then repeated these searches in Google Scholar during this same time frame and classified results by source; i.e., scientific journals, graduate student theses, Arthropods of Canadian Grasslands chapters, books (and book chapters), and “other” (Fig. 2). Citations from other Arthropods of Canadian Grasslands chapters were excluded from the “book” category to avoid overestimating awareness of the Arthropods of Canadian Grasslands series. The “other” category included government reports, reference guides, or sources that did not clearly fall into the remaining categories. A total of 268 citations to the 53 chapters in the Arthropods of Canadian Grasslands series were identified, of which 19 were self-citations. Excluding self-citations and citations in Arthropods of Canadian Grasslands chapters, the most cited chapters were reviews of taxonomic groups that included key pest species (Hamilton and Whitcomb Reference Hamilton and Whitcomb2010; van Herk and Vernon Reference van Herk and Vernon2014) or topics of broader interest; e.g., weather (McGinn Reference McGinn2010), arthropods of cattle dung (Floate Reference Floate2011a), and arthropods introduced as biocontrol agents (De Clerck-Floate and Cárcamo Reference De Clerck-Floate and Cárcamo2011). Examination of journal titles and the thesis granting universities identified many located outside of North America.

Fig. 2 Sources identified using Google Scholar that cite chapters in the Arthropods of Canadian Grasslands monograph series. The Arthropods of Canadian Grasslands (ACG) category identifies self-citations, i.e., citations to other chapters in the Arthropods of Canadian Grasslands monograph series. The “other” category includes government reports, reference guides, or sources that do not clearly fall into the remaining categories.

As of 31 March 2017, only about 17 hard copies have been sold for each volume of the Arthropods of Canadian Grasslands series via the print-on-demand option. Thus, providing this option appears to have provided little tangible benefit for dissemination of the series. Uptake of the print-on-demand option has been greater for other BSC monographs; e.g., 70 copies of A Handbook to the Ticks of Canada (Ixodida: Ixodidae, Argasidae) (Lindquist et al. Reference Lindquist, Galloway, Artsob, Lindsay, Drebot, Wood and Robbins2016) have been sold in the first four months since its release (D. Langor, personal communication). However, linking to the chapters through online sites shows that chapters are being downloaded and viewed. A paper on stoneflies (Plecoptera) of the Prairie Provinces in volume 3 (Dosdall and Giberson Reference Dosdall and Giberson2014) was downloaded through ResearchGate (www.researchgate.net) more than 100 times between 5 January 2016 and 20 April 2017. Since 1 January 2017, the Arthropods of Canadian Grasslands webpage (http://biologicalsurvey.ca/monographs/read/17) has been accessed 383 times (J. Elofson, personal communication).

What have we learned from the grassland arthropods initiative?

The BSC has been well positioned to lead an initiative assessing arthropod diversity in the prairie grasslands, due to its collaborative approach in bringing together researchers to synthesise known information and generate new data (Danks Reference Danks2016, Reference Danks2017). Through meetings organised by the BSC, entomologists from across the country met in Ottawa, Ontario at least annually to discuss knowledge gaps and propose solutions to fill them. These meetings, coupled with symposia at annual entomology meetings and organised field trips (BioBlitzes) to different habitats, engaged a broad community of researchers who ultimately contributed to the projects and their outputs, including monographs and newsletters (Danks Reference Danks2017). A broader understanding of the arthropod species composition of prairie grasslands has been achieved through the grasslands project, as well as information on the remaining gaps. In the sections below, we summarise some of the findings of the project and provide suggestions for future directions.

Diversity patterns

Summaries from the Arthropods of Canadian Grasslands monograph series (Shorthouse and Floate Reference Shorthouse and Floate2010; Floate Reference Floate2011b; Cárcamo and Giberson Reference Cárcamo and Giberson2014; Giberson and Cárcamo Reference Giberson and Cárcamo2014) show that taxonomic knowledge for the Prairies Ecozone varies markedly among arthropod groups, but is generally more complete for insects than for non-insects (see also Table 1 for additional references). Species lists are generally complete for grasslands Lepidoptera (Pohl et al. Reference Pohl, Schmidt, Lafontaine, Landry, Anweiler and Bird2014) and Orthoptera (Vickery and Kevan Reference Vickery and Kevan1985), but non-lepidopteran orders may have both well known or sparsely studied families, or species lists that are defined by political jurisdiction rather than by ecozone; e.g., Coleoptera (Bousquet et al. Reference Bousquet, Bouchard, Davies and Sikes2013). This latter deficiency has been partially addressed with the publication of Prairies Ecozone checklists (along with habitat and ecological information in many cases) for several families of beetles in the Arthropods of Canadian Grasslands series or other recent monographs. These include the Carabidae (Holliday et al. Reference Holliday, Floate, Cárcamo, Pollock, Stjernberg and Roughley2014), Elateridae (van Herk and Vernon Reference van Herk and Vernon2014), Tenebrionidae (Bouchard and Bousquet Reference Bouchard and Bousquet2014), Dytiscidae (Larson et al. Reference Larson, Alarie and Roughley2000), and families of the Curculionoidea (Anderson et al. Reference Anderson, Bouchard and Douglas2014). Staphylinidae (rove beetles) have been largely overlooked at the ecozone level, even though it is the most speciose beetle family in Canada; i.e., 1652 recorded species and subspecies (Klimaszewski et al. Reference Klimaszewski, Godin, Bourdon, Langor, Lee and Horwood2015). Ecozone synopses for Chrysomelidae, Scarabaeidae, and other groups of beetles have not yet been done. For Hemiptera, synopses are now available for Heteroptera (Scudder Reference Scudder2014a), Aphidoidea (Foottit and Maw Reference Foottit and Maw2014), and Cicadellidae (Hamilton and Whitcomb Reference Hamilton and Whitcomb2010; Hamilton Reference Hamilton2014). Within the Hymenoptera, there are extensive checklists for Apiformes (Sheffield et al. Reference Sheffield, Frier and Dumesh2014), Braconidae (Sharanowski et al. Reference Sharanowski, Zhang and Wanigasekara2014), Formicidae (Glasier and Acorn Reference Glasier and Acorn2014), and Ichneumonidae (Schwarzfeld Reference Schwarzfeld2014). Among families of Diptera, there are recent synopses for Asilidae (Cannings Reference Cannings2014b), and the biting flies (Simulidae – Currie (Reference Currie2014) and Ceratopogonidae, Culicidae, and Tabanidae – Lysyk and Galloway (Reference Lysyk and Galloway2014)). However, only 369 species of flies were reported in the Arthropods of Canadian Grasslands series (combined across families).

The prairies also support many species of aquatic insects that inhabit natural wetlands, ponds, and rivers (Wrubleski and Ross Reference Wrubleski and Ross2011). These aquatic groups are generally poorly known, with the exception of the biting flies mentioned above, primarily because there are few taxonomic keys for immature stages in most groups. Immature stages (which live in water) are commonly collected in aquatic surveys, and identification is usually to “lowest practical taxon”, which for most aquatic insect groups is to genus. The comprehensive Introduction to the aquatic insects of North America (Merritt et al. Reference Merritt, Cummins and Berg2008) provides genus-level keys for most groups, and lists regional species keys where available, but few of these target regions in Canada, including the Prairies Ecozone. There are many lists of taxa associated with specific prairie streams or ponds (e.g., Cobb and Flannagan Reference Cobb and Flannagan1990; Miyazaki and Lehmkuhl Reference Miyazaki and Lehmkuhl2011; Parker Reference Parker2017), but only a few of these lists identify the majority of taxa to species; e.g., Cobb and Flannagan (Reference Cobb and Flannagan1990). Therefore, there are few current synthetic treatments for aquatic insects of the Prairies Ecozone, though exceptions include the Odonata (Cannings Reference Cannings2014a), Plecoptera (Dosdall and Giberson Reference Dosdall and Giberson2014), and the Ephemeroptera in Saskatchewan (Webb Reference Webb2002). For some aquatic insect groups, up-to-date checklists for broad regions or jurisdictions are available online, but these do not allow for analyses at the ecozone level; e.g., Ephemeroptera (Jacobus and McCafferty Reference Jacobus and McCafferty2017), Plecoptera (DeWalt et al. Reference DeWalt, Maehr, Neu-Becker and Stueber2017), and Trichoptera (Rasmussen and Morse Reference Rasmussen and Morse2016).

From existing checklists, we can conclude that the Prairies Ecozone supports at least 25% of the ~34 000 species of arthropods so far recorded in Canada (Danks Reference Danks1988). This estimate derives from a compilation of taxa reported from the Prairie Provinces, in most cases specific to the Prairies Ecozone (Table 1). These lists, taken from the Arthropods of Canadian Grassland series, identify about 8200 species, representing 2518 genera in 309 families, or 22 orders in nine classes. Extrapolating from the findings for well-studied groups, this percentage is expected to increase with further taxonomic studies. Among speciose insect orders, our taxonomic knowledge for the Prairies Ecozone is perhaps most complete for Lepidoptera (2232 species, representing 43% of the Canadian total – Pohl et al. Reference Pohl, Schmidt, Lafontaine, Landry, Anweiler and Bird2014), Hemiptera (Heteroptera) (41% of the known Canadian fauna – Scudder Reference Scudder2014a), and Odonata (59% of the known Canadian fauna – Cannings Reference Cannings2014a). For Coleoptera, Diptera, and Hymenoptera, knowledge of the fauna varies widely by family. Ground beetles (Coleoptera: Carabidae) have been extensively studied in Canada (Lindroth 1961–Reference Lindroth1969) so few additional species are expected, and 44% (398 species) of the Canadian total occurs in the Prairies Ecozone (Holliday et al. Reference Holliday, Floate, Cárcamo, Pollock, Stjernberg and Roughley2014). This compares to only 22% and 34% (respectively) of the Canadian darkling beetles (Tenebrionidae – 31 species) and weevils (Dryophthoridae – nine species, Brachyceridae – 13 species, Curculionidae – 273 species) found in the Prairies Ecozone (Anderson et al. Reference Anderson, Bouchard and Douglas2014; Bouchard and Bousquet Reference Bouchard and Bousquet2014). The reported 387 species of bees (Hymenoptera: Apoidea, Apiformes) in the Ecozone represents 48% of the Canadian fauna (Sheffield et al. Reference Sheffield, Frier and Dumesh2014). Among the well-known biting Diptera, only 11% (18 species) of the Canadian total for Simuliidae (black flies) are considered Prairies Ecozone residents (Currie Reference Currie2014), and 30% (25 species) of Culicidae (mosquitoes) are found in the zone (Lysyk and Galloway Reference Lysyk and Galloway2014).

Groups dominated by grassland specialists predictably have a high proportion of their Canadian species resident in the Prairies Ecozone. Orthoptera (grasshoppers) have been well studied in Canada (Vickery and Kevan Reference Vickery and Kevan1985). Grassland habitats in British Columbia and the Yukon support 87 species, representing 57% of the Canadian fauna (Miskelly Reference Miskelly2014). The species richness of the Prairies Ecozone may represent 65% of the Canadian fauna (Miskelly Reference Miskelly2014).

The taxonomy of non-insect terrestrial arthropods is generally unresolved (Table 1), leading to difficulties in predicting diversity patterns for these groups. For Acari, perhaps 70% or more of the estimated 10 000–15 000 species in Canada are undescribed (Lindquist et al. Reference Lindquist, Ainscough, Clulow, Funk, Marshall and Nesbitt1979; Lumley et al. Reference Lumley, Beaulieu, Behan-Pelletier, Knee, Lindquist and Mark2013). A square metre of grassland soil may contain up to 250 species and 150 000 mites (Behan-Pelletier Reference Behan-Pelletier2003). In addition, studies of grassland soils have generally focussed on Oribatidae mites, even though Prostigmatidae mites may be numerically more dominant (Behan-Pelletier and Kanashiro Reference Behan-Pelletier and Kanashiro2010). About 200 species of mites that feed above-ground on plants (Beaulieu and Knee Reference Beaulieu and Knee2014) are expected in the Prairies Ecozone. Interestingly, there appears to be little faunistic overlap between above-ground plant mites and soil mites. The two groups share 14 families and seven genera, but only two species (Beaulieu and Knee Reference Beaulieu and Knee2014; Galloway et al. Reference Galloway, Proctor and Mironov2014). About 200 species of mites are parasites of birds of the Prairies Ecozone (Galloway et al. Reference Galloway, Proctor and Mironov2014). If these estimates of species richness are correct, then 50% of plant feeding and 80% of parasitic species are known. In contrast, our taxonomic knowledge of ticks (Acari: Ixodida) is essentially complete. A recent synthesis reviews each of the 40 species (10 genera) reported in Canada (Lindquist et al. Reference Lindquist, Galloway, Artsob, Lindsay, Drebot, Wood and Robbins2016).

The taxonomy of Collembola (class Entognatha) is better known than that of mites, with a North American species key provided by Christiansen and Bellinger (Reference Christiansen and Bellinger1998). Skidmore (Reference Skidmore1995) provides a checklist for 412 species in Canada of an estimated total number of roughly 520 species expected (Danks Reference Danks1988). We are aware of only three studies from the Prairie Provinces that report on the diversity of Collembola, and only two of these report on the Prairies Ecozone. Ten species were reported from seven sites in the Boreal Ecozone in northcentral Alberta (Berg and Pawluk Reference Berg and Pawluk1984). A total of 12 species were reported from a site in southern Alberta (Scheffczyk et al. Reference Scheffczyk, Floate, Blanckenhorn, Düring, Klockner and Lahr2016). In all, 16 species were identified from tallgrass prairie, although species richness was likely underestimated due to methodology (Aitchison Reference Aitchison1979). Using results of Skidmore (Reference Skidmore1995) and diversity studies for grasslands in the United States of America, Lindo (Reference Lindo2014) provides a checklist of 69 species of Collembola known or likely to occur in the Prairies Ecozone.

Other non-insect arthropods and their relatives are even less known. There have been no studies in the Prairies Ecozone to assess species richness in Pauropoda (pauropods), Symphyla (garden centipedes), or terrestrial Crustacea (i.e., terrestrial Isopoda; wood lice, and pill bugs or sow bugs) (Snyder Reference Snyder2014). Only 10 species of Myriapoda (millipedes, centipedes) have been documented for the prairies (Snyder Reference Snyder2014), although 200 species were estimated to occur in Canada (Danks Reference Danks1988). Given the generally dry climate of the Ecozone, the diversity of these groups is expected to be low. Tardigrades (water bears or moss piglets) were included as members of Arthropoda by Danks (Reference Danks1988) with an estimated Canadian total of 210 species. Tardigrades are no longer considered arthropods, although their phylogenetic relationships remain somewhat contentious (Giribet and Edgecombe Reference Giribet and Edgecombe2012). They may have a rich diversity in the Prairies Ecozone given their remarkable ability to survive extreme temperatures and desiccation (Horikawa Reference Horikawa2012). In a recent survey in three southern Alberta sites, an average of 20 tardigrades was collected per gram of moss, but these were not identified to species (Sorensen and Goater Reference Sorensen and Goater2016). A total of 12 species or species groups of tardigrades were collected in an urban park in Calgary, Alberta, for which eight were first reports for the province and two were new records for Canada (Grothman Reference Grothman2011).

Our knowledge of speciose groups of non-insect arthropods is most complete for spiders, but knowledge gaps remain, and a grassland synthesis is still lacking. Danks (Reference Danks1988) and Bennett (Reference Bennett1999), respectively, estimated a total of 1400 and 1500 described and undescribed species of spiders in Canada; Paquin et al. (Reference Paquin, Buckle, Dupérré and Dondale2010) provide a species list of 1413 species for Canada and Alaska. Assuming a Canadian total of 1500 species, 94% of the spider species in Canada should have been described. However, recent results obtained with DNA barcoding indicate that the total number of species in Canada may range from 1900–2200, in which case 30–50% remain undiscovered (Blagoev et al. Reference Blagoev, deWaard, Ratnasingham, deWaard, Lu and Robertson2016). A complete synthesis for spiders of the Prairies Ecozone is not available. However, 767 species were recorded from all Ecozones in the Canadian Prairie Provinces (Cárcamo et al. Reference Cárcamo, Pinzón, Leech and Spence2014), and 356 species are known from the grasslands and parkland areas of Alberta and Saskatchewan (Holmberg and Buckle Reference Holmberg and Buckle2002). Extrapolating from the insect taxa mentioned above, 40% or more of the national diversity for many groups occurs in the Prairies Ecozone. If there is a similar relationship for spiders, and assuming a total fauna of 1900–2200 species (Blagoev et al. Reference Blagoev, deWaard, Ratnasingham, deWaard, Lu and Robertson2016), then there are perhaps 760–880 species in the Prairies Ecozone.

The need for long-term and/or broad-scale studies

Comparison of the available checklists with predictions of total species richness from DNA barcoding studies (e.g., Hebert et al. Reference Hebert, Ratnasingham, Zakharov, Telfer, Levesque-Beaudin and Milton2016, Sheffield et al. Reference Sheffield, Heron, Gibbs, Onuferko, Oram and Best2017) shows that our knowledge of grassland arthropods is incomplete, except in the best-known taxonomic groups. Many checklists, including some of those summarised above, result from sampling brief windows of opportunity during the collecting season, perhaps as little as a few hours on one day of the year. A combination of factors, including weather, time of day, and phenology of component species, will affect the number of species collected, but the total will be less than the total species actually present. One solution is more intensive sampling throughout a season and in multiple habitats, and more ideally, over several years in succession. Some examples of long-term studies in grassland areas include the Ojibway Prairie in southwestern Ontario (Paiero et al. Reference Paiero, Marshall, Pratt and Buck2010), the St. Charles Rifle Range near Winnipeg Manitoba (Roughley et al. Reference Roughley, Pollock and Wade2010; Wade and Roughley Reference Wade and Roughley2010), the Criddle/Vane homestead at Aweme, Manitoba (Holliday et al. Reference Holliday, Floate, Cárcamo, Pollock, Stjernberg and Roughley2014), aquatic insects of the Saskatchewan River near Saskatoon (Miyazaki and Lehmkuhl Reference Miyazaki and Lehmkuhl2011), the wildlife reserve at Suffield Canadian Forces Base in Alberta (Finnamore and Buckle Reference Finnamore and Buckle1999), and the antelope brush grasslands near Osoyoos, British Columbia (Scudder Reference Scudder2000).

One of the most noteworthy of these locations has been the Criddle/Vane homestead at Aweme, located southeast of Brandon, Manitoba (Holliday et al. Reference Holliday, Floate, Cárcamo, Pollock, Stjernberg and Roughley2014). Arthropods have been collected sporadically at the site for over 115 years starting with Norman Criddle and his family (Holliday Reference Holliday2006). Representatives of the Moist Mixed Grassland and Lake Manitoba Plains Ecoregions are within a few kilometres of the homestead, along with remnant patches of tallgrass prairie. Records for carabid beetles collected at the site illustrate the value of such long-term data sets. Nearly 200 species have been collected at Aweme since 1900, representing 54% of all species known from Manitoba (Holliday et al. Reference Holliday, Floate, Cárcamo, Pollock, Stjernberg and Roughley2014). The long-term record has also allowed researchers to track changes in species composition in recent studies compared with the 1900s. The introduction of crop monocultures and the use of insecticides are the main factors influencing ground beetle diversity (Holliday et al. Reference Holliday, Floate, Cárcamo, Pollock, Stjernberg and Roughley2014); not surprisingly, carabid diversity is low in agroecosystems.

One challenge to filling the knowledge gap about arthropods in the Prairie Ecozone is that some existing data and studies are in formats or collections that are not easily accessible to other researchers. Many lists and associated ecological information have been published in government or agency reports (e.g., Finnamore and Buckle Reference Finnamore and Buckle1999; Scudder Reference Scudder2000), and some of these are difficult to access. In other cases, amateur or retired entomologists have amassed collections or data that reside with the collector. Retired Memorial University entomology professor David Larson currently lives on a ranch south of Maple Creek, Saskatchewan on the southern slope of the Cypress Hills. His study of grassland arthropod diversity over the past 20 years has produced many new records and a wealth of collected material, but recent additions to the list are so far unpublished. Larson’s working dataset updating the checklist of Saskatchewan Coleoptera (D. Larson, personal communication) lists about 2700 species, which dramatically increases the number of known species for Saskatchewan (compare to 2312 species in Hooper and Larson (Reference Hooper and Larson2012) and 2679 species in Bousquet et al. (Reference Bousquet, Bouchard, Davies and Sikes2013)). For the rove beetles alone (Staphylinidae), his sampling produced 12 new species and 50 new records for Saskatchewan (Klimaszewski et al. Reference Klimaszewski, Larson, Labrecque and Bourdon2016). Larson’s collections have also increased the known number of species of Lygaeoidea (Hemiptera) from the Prairie Provinces from 48 (Maw et al. Reference Maw, Foottit, Hamilton and Scudder2000) to 68, including 50 species from southwestern Saskatchewan (most records published in Scudder Reference Scudder2009, Reference Scudder2010b, Reference Scudder2012, Reference Scudder2014a).

The need for more studies, especially for underrepresented taxa and habitats

Throughout its history, the BSC has worked to identify and fill knowledge gaps by encouraging researchers and interested amateurs to study poorly known taxa and regions. One objective of the Arthropods of Canadian Grasslands monograph series is to identify where information is lacking and direct study to those areas. For example, 398 species of carabids are known from the Prairies Ecozone, but no studies of this group have been done thus far in the Fescue Grassland, Cypress Upland, or the Boreal Transition Ecoregions (Holliday et al. Reference Holliday, Floate, Cárcamo, Pollock, Stjernberg and Roughley2014).

The BSC has sponsored BioBlitzes and curation blitzes to fill some of these gaps. Bioblitzes in the Prairies Ecozone contribute to the deposition of numerous specimens in the Canadian National Collection, regional collections at Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada research centres, and in university collections across the country. They have also introduced researchers and other interested collectors to one another and to new habitats that then become the focus of further study. However, specimens collected during these events can result in large numbers of unidentified specimens being deposited in museum collections due to a lack of taxonomic expertise. Thus, the BSC arranges curation blitzes that bring together taxonomists with diverse expertise to examine and identify this material. These, coupled with “citizen science” initiatives that include public participation, can help to fill in knowledge gaps in a cost-effective manner, especially for charismatic taxa such as butterflies, ladybird beetles (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae), bumble bees (Hymenoptera: Apidae), and dragonflies (Odonata). For example, an estimated 1.3 million volunteers recently participated in 388 biodiversity research projects in different locations around the world, reflecting an annual in-kind labour contribution of US $2.5 billion (Theobald et al. Reference Theobald, Ettinger, Burgess, DeBey, Schmidt and Froehlich2015). Citizen scientists are an untapped resource of high potential for understanding species response to habitat loss and fragmentation, biological invasions, and the effects of climate change on grassland arthropods. Another advantage to launching citizen science projects within grasslands of Canada is that they have the potential to promote the public’s understanding of the role of insects in ecosystems including aquatic ecosystems, agroecosystems, and urban ecosystems.

Summary

The Arthropods of Canadian Grasslands monograph series is the culmination of a near 40-year project that reflects the efforts of a network of individuals working under the loose direction of the BSC. The initial objectives were to increase awareness of the vanishing grasslands of Canada and their associated arthropods, identify knowledge gaps, and provide direction for future studies of arthropods in these habitats. These objectives had to be expanded to increase the collaborator network. Thus, contributions to the series include general descriptions of the ecoregions that comprise the Prairies Ecozone, climate, a history of European colonisation, synopses of arthropod taxonomic groups, and studies of arthropod diversity in both select habitats (including agroecosystems) and specific grassland sites. The health of the network is fostered through newsletters, field trips, and conference symposia. To highlight the plight of native grasslands in Canada to a broad audience, contributors to the series are encouraged to write not just for an academic audience, but in a manner that also will engage teachers, students, farmers, ranchers, naturalists, and other individuals interested in the Prairies Ecozone. Contributors also are encouraged to make use of colour images when possible for the same reason. This strategy of engaging researchers through activities sponsored by the BSC has thus far resulted in four volumes of Arthropods of Canadian Grasslands monograph series, has built a strong research network, and has fostered numerous collaborations. These collaborations have resulted in dozens of articles in scientific journals and newsletters, and book chapters, most of which are freely available online; e.g., see appendix 4.5 in Danks (Reference Danks2016) and references cited in this article. However, there remains a need for further study to better capture the diversity and ecology of Canadian grasslands arthropods, and to assess the effects of human activities in the Prairies Ecozone.

Acknowledgements

This is Lethbridge Research and Development Centre publication number 38717040.