Introduction

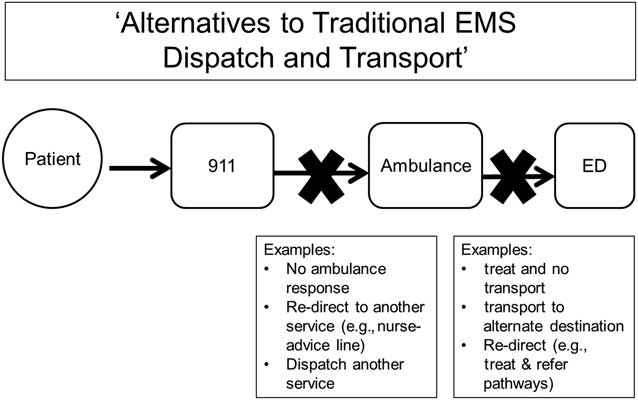

In recent years, there has been an increase in emergency medical services (EMS) services that are alternatives to EMS dispatch or EMS transport to the emergency department (ED). Traditionally, ambulances are dispatched for all 911 callers. All patients are transported to the ED, unless the patient or decision maker refuses transport. A “multiple option decision point” has been previously described as an alternative, in which a decision on the need for EMS transport could be made at two points: at the EMS dispatch centre and on scene,Reference Gratton, Ellison and Hunt 1 , Reference Neely 2 in an attempt to “get the right patient to the right place at the right time” (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Alternatives to Traditional EMS Dispatch and EMS Transport to the ED.

Emergency medical dispatching conceptually consists of two major tasks: call processing and dispatching of EMS resources. Call processing can be further broken down into: 1) triage (deciding whether to send emergency resources or not); 2) prioritization (how quickly to send resources; and 3) choosing the level of resources required.Reference Farand, Leprohon and Kalina 3 Alternatives to EMS dispatch may be decided during the triage or choosing resources stages. On-scene alternatives to EMS transport to the ED include protocols to treat the patient and leave them on scene (“treat and release”), or to treat and refer to other parts of the healthcare system. These types of alternatives have been included in the expanding scope of “community paramedicine,” also more recently described as “mobile integrated healthcare” and “patient-centered EMS.”Reference Morganti, Alpert and Margolis 4

A narrative literature review of on-scene alternatives to ED transport conducted by Snooks and colleagues 10 years ago found that there were few comparative studies and that data were too scarce to determine the safety of such programs.Reference Snooks, Dale and Hartley-Sharpe 5 More recently, a community paramedicine systematic review drew similar findings.Reference Bigham, Kennedy and Drennan 6 This variance in the interventions studied, methods used, and outcomes measured led to a body of knowledge that is difficult to synthesize and interpret, and nearly impossible to generalize to local settings.

To aid future researchers and those measuring quality and safety in such alternative EMS programs, this broad scoping review sought to identify, catalogue, and describe the outcome measures reported by such programs.

Methods

Study design

This scoping review was based on Arksey and O’Malley’s methodological framework,Reference Arksey and O'Malley 7 and consisted of three searching techniques: 1) a systematic search of bibliographic databases for research literature on the topic; 2) a hand search of websites for grey literature; and 3) a snowball search of the reference lists of articles that met the inclusion criteria. The bibliographic and grey literature searches were purposefully broad in order to capture as much of the research conducted in this field as possible.

Data source

The bibliographic database search was developed using a pearl growing search strategy, in which key articles identified by the investigators were mined for index terms and keywords.Reference Schlosser, Wendt and Bhavnani 8 - Reference Papaioannou, Sutton and Carroll 11 Seven articles were used for this purpose.Reference Dale, Higgins and Williams 12 - Reference Studnek, Thestrup and Blackwell 18 The database search was conducted in PubMed, EMBASE, CINAHL and the Cochrane Library in 2012 and repeated on May 19, 2014. The search was created using a combination of Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and keywords in PubMed, and mapped to the other databases using their designated thesauri. The three main concepts of interest in this search were: 1) 911 callers/EMS patients; 2) interventions and services provided by EMS; and 3) decision making. These were combined with “AND,” and “OR” (Appendix A). English and human subject limiters were applied.

The grey literature search was conducted from November 4, 2012 to December 4, 2012 by two investigators and a paramedic, who hand-searched a list of websites (Appendix B). This list was generated from suggestions made by investigators, as well as an exploratory search of government and health association websites for possible sites of interest. 19 , Reference Giustini 20 The searches and findings were documented, along with any links followed. The snowball search was conducted by reviewing the titles of articles in the reference lists of included articles.

Study selection

For a record to be included, it had to contain each of the following: a) the population was 911 callers or EMS patients, b) it described an alternative to traditional EMS dispatch OR to transport to the ED, and c) it reported an outcome measure. Abstracts were excluded. Reviews were not included, although reference lists were hand-searched for primary reports.

Review for inclusion of the bibliographic database search was first conducted by title by a single author. Review for inclusion by abstract, full text article, and retrieved grey literature was conducted by two independent authors with a third author serving as adjudicator.

Data extraction

The intervention described in each report was categorized as either an alternative to EMS dispatch or alternative to EMS transport to ED. Each outcome reported in the included reports was categorized into one of the following categories, which were determined a priori by study team knowledge of the literature and consensus: 1) clinical, 2) safety, 3) service utilization, 4) patient satisfaction, 5) cost, 6) accuracy of decision, 7) process outcome, and 8) other. The included reports were divided among team members for abstraction. Study team members determined the Level of Evidence (Table 1), Direction of Evidence and outcome category for each study through discussion and consensus. The Direction of Evidence for each study was based on the results of the primary outcome (adapted from the Canadian Prehospital Evidence-based Practice Project). 40

Table 1 Level of evidence scale (adapted from the International Liaison Committee on ResuscitationReference Sayre, O'Connor and Atkins 39

Results

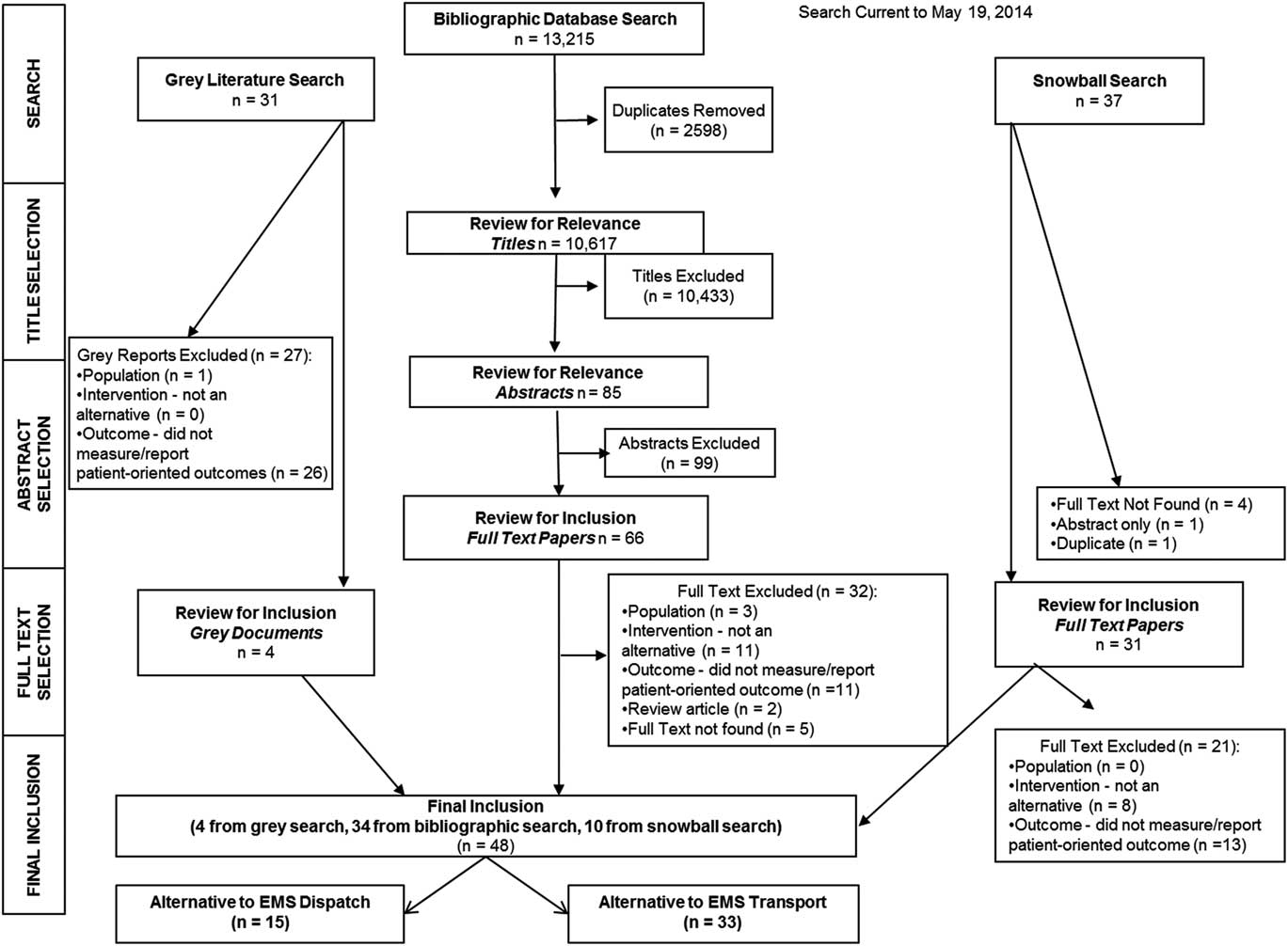

In total, 13,215 records were retrieved through the bibliographic database searches, including the seven pearl articles. These were imported into the reference management citation software Refworks (Proquest, Bethesda, MD, USA); 2,598 duplicates were then eliminated, leaving 10,617 unique records. Thirty-seven websites were hand-searched for grey literature, in which 31 records of interest were identified. A total of 48 records met the inclusion criteria: 34 from the bibliographic search, four from the grey literature search, and 10 from the snowball search (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Scoping review flow diagram.

Outcome measures reported on alternatives to EMS dispatch

Fifteen reports were categorized as alternatives to EMS dispatch (Table 2). One report described two separate studies.Reference Turner, Snooks and Youren 25 Articles were from the UK (n=6), the United States (n=6), Canada (n=2), and Iran (n=1). Eleven of these EMS systems were paramedic-based,Reference Dale, Higgins and Williams 12 , Reference Dale, Williams and Foster 13 , Reference Schmidt, Neely and Adams 15 , Reference Smith, Culley and Plorde 16 , Reference Studnek, Thestrup and Blackwell 18 , 21 - Reference Infinger, Studnek and Hawkins 26 two were physician-based with basic emergency medical technicians,Reference Farand, Leprohon and Kalina 3 , Reference Leprohon and Patel 27 and in one report the type of EMS system was unclear.Reference Alizadeh, Panahi and Saghafinia 28 The following interventions were studied: transferring 911 callers to nurse-advice lines (n=6), EMS dispatch providing advice or self-care instructions (n=4), alternative EMS response being dispatched (n=3), and identification of low acuity calls that do not require EMS response (n=2). Studies were most commonly those without a comparison group (6/16), and studies with alternative designs, such as patient surveys or models (4/16). There were two uncontrolled designs with a comparison group, three studies with a retrospective comparison group and one controlled trial. The results of five studies were considered supportive of the intervention, 10 studies had neutral results and one study had opposing results. The outcome categories, reported by the greatest number of reports, were service utilization (n=12) and decision accuracy (n=7) (Table 2). In total, there were 24 unique outcomes reported. The outcome categories with the greatest number of specific different outcomes were service utilization (n=8), accuracy of decision (n=4), safety (n=3), call times (n=3), cost (n=3), patient satisfaction (n=2), and process outcomes (n=1).

Table 2 Characteristics and outcomes reported: alternatives to EMS dispatch

* total greater than number of included reports because Turner 2006 report contained two studies with different patient samplesReference Turner, Snooks and Youren 25

Outcome measures reported on alternatives to EMS transport

Thirty-three reports were categorized as alternatives to EMS transport to the ED, all of which were from paramedic-based systems (Table 3). Sixteen studies were from the UK, 13 were from the US, two from Australia, one from Sweden and one from Canada. Twelve reported on expanded-scope EMS programs (such as the UK emergency care practitioner), 10 reported on EMS-initiated non-transport, six described programs in which calls were referred to another health service, three were of treat-and-release protocols, one assessed using telemedicine to expand consults by EMS for non-transport, and one studied providing patients with an alternative mode of transport to the ED (via taxi). The majority of study designs were those without a comparison group (n=14), followed by studies with a retrospective comparison group (n=6). There were three randomized controlled trials, three studies with a non-randomized comparison group, and three studies from another population or simulation. There were four protocols of controlled trials. The outcome categories most reported were service utilization (n=14), safety (n=12), patient satisfaction (n=10), accuracy of decision (n=9), and clinical outcomes (n=9) (Table 3). In total, there were 50 different unique outcomes reported. The outcome categories with the greatest number of specific different outcomes were service utilization (n=8), accuracy of decision (n=7), clinical outcomes (n=7), call times (n=7), process outcomes (n=6), safety (n=6), cost (n=5), patient satisfaction (n=2), and other (n=2).

Table 3 Characteristics and outcomes reported: alternatives to EMS transport studies

Discussion

The purpose of this broad scoping literature review was to identify and catalogue the outcome measures used to study and report on alternatives to EMS. Scoping reviews are valuable for mapping complex topics to increase understanding.Reference Arksey and O'Malley 7 As we sought to identify all outcome measures used in any type of “alternative to traditional EMS dispatch or transport” program, this approach was most suitable. Forty-eight publications of over 1,000,000 patients for a wide variety of programs and interventions were located and included. These publications were very heterogeneous in design, population, and outcomes. The categories of outcomes most reported in the alternatives to traditional EMS dispatch reports were service utilization and accuracy of decisions, with 12 different sub-categories. In the alternatives to traditional EMS transport reports, the outcome categories with the most reported outcomes were service utilization, safety, clinical outcomes, and call times, with 29 sub-categories. This review revealed that similar outcomes are measured in many different ways. For example, adverse events have been examined by asking patients directly, through retrospective examination of health records, and through panel assessments of whether decisions were safe.Reference Dale, Williams and Foster 13 , Reference Smith, Culley and Plorde 16 , Reference Turner, Snooks and Youren 25 This variance was also identified in a recent focus group study of US EMS services, in which safety was assessed in multiple ways, including by retrospective chart reviews and follow-up phone calls with patients.Reference Morganti, Alpert and Margolis 4

Just as this review was useful for identifying outcomes that are used frequently, it is also valuable to shed light on under-reported outcome categories. In the alternatives to dispatch studies, clinical outcomes were not reported, and process outcomes were only reported in one study. The least-used outcome category in the “alternatives to transport” studies was the “other” outcomes to identify a potential target program population, reported in two studies,Reference Haskins, Ellis and Mayrose 29 , Reference Kamper, Mahoney and Nelson 30 and uptake of advice by patients was even more infrequent, studied in just one publication.Reference Mikolaizak, Simpson and Tiedemann 31 There are additional outcomes that could be of great value but that have not been used in any of these studies. For example, it would be of great value to assess the effect of such services on the response times of other EMS units as a times outcome.

Alternative to dispatch

As noted in a recent systematic review, ambulance-dispatch-based secondary triage has been implemented in many locations, as a strategy to avoid dispatching ambulances to low-priority calls, which may also help with ED overcrowding challenges.Reference Eastwood, Morgans and Smith 32 Our scoping review captured the same articles included in this review by Eastwood et al, with the exception of a descriptive publication that did not report on outcomes.Reference Fox, Rodriguez and McSwain 33 Our review located 15 publications (16 studies), of which the majority reported on EMS dispatch programs that diverted callers to either nurse-advice lines or alternate EMS services (other than standard emergency ambulance dispatch). The remaining programs provided advice or self-care instructions, or identified low-acuity patients who did not require an EMS response. To fully understand the effect of all of these programs that are alternatives to EMS dispatch, uniform outcome measures need to be employed across studies. This review examined the structure, safety, and success of such systems, and found evidence from six studies that the services were safe and patients were satisfied. Success of referrals, an outcome of the review, was not well-addressed in the results. Recent studies with supportive results were of low quality and with small- to moderate-sized samples. These studies focused on reporting outcomes on service utilization.

Alternatives to transport

Previous authors have noted that determining the need for EMS transport cannot be solely based on the medical necessity for the patient to be seen in the ED.Reference Brown, Hubble and Cone 34 As noted by Chu et al, any tools to evaluate eligibly of low-acuity patients for an alternative to ambulance transport must include assessing patient ability to ambulate.Reference Chu, Gregor and Maio 35 Some studies have explored the complexity of transport decisions and the many factors that must be considered by EMS responders.Reference Porter, Snooks and Youren 36 , Reference Jensen, Travers and Marshall 37 Many of the 33 studies included in this review include strategies within the programs reported to provide patients with access to other services, expanded care on scene, or other means of transport to the ED. The body of knowledge related to “mobile integrated healthcare” or “community paramedicine” has become multi-faceted and complex, with many services tailored specifically for the population or community they are aiming to better serve. This reinforces the need for consistent outcome measures for evidence-users to increase their understanding of the effects of such programs. In our review, recent supportive studies included a randomized controlled trial and a large comparison study, both of which reported on service utilization outcomes, and a cost analysis based on a large sample.Reference Alpert, Morganti and Margolis 42 , Reference Halter and Ellison 52 , Reference Mason, Knowles and Colwell 59 There were four studies included that contained opposing evidence, all of which were studies without a comparison group. Also included were four protocol manuscripts, which describe upcoming randomized trials, which will add valuable high-quality evidence.

Next steps

Two key challenges have been identified that impede further evidence synthesis in this body of literature. 1) The programs or interventions studied are extremely heterogeneous. We appreciate the importance of developing programs that meet specific community needs. However, these programs or interventions should be grouped into main categories that will facilitate comparison and pooling of findings. For example, studies should first be categorized according to whether they were an alternative to EMS dispatch or transport. If it is an alternative to EMS dispatch, the intervention service may be categorized as: to nurse-advice line, to referral pathway (such as family practice clinic), to alternative EMS response, given advice or self-care instructions, or other. If it is an alternative to EMS transport, the intervention service may be categorized as: paramedic treat and release, EMS-initiated non-transport, call or refer to another health service or referral pathway, consult with a physician or other provider, expanded scope EMS delivery, alternative mode of transport to the ED, or other. 2) Many different approaches have been used to measure similar outcomes. What is now required is to carry out a consensus project to determine which outcomes are most important to use. A taxonomy of standard terms as well as outcome definitions would allow valid comparisons across systems. In the US, a consensus session led to the publication of a National Agenda for Community Paramedicine Research,Reference Patterson and Skillman 38 which determined research priorities, but did not give direction on which are the ideal outcomes to use, and what method(s) to use. Categorizing outcomes into type by process (measures of actions or functions), system (measures of how the system works), and outcome (patient-related changes in outcome that are attributable to care received) would further harmonize research comparisons (Table 4).

Table 4 Outcome categories, specific options and measurement considerations

Limitations

A scoping review was determined to be an appropriate evidence synthesis strategy for this topic, as opposed to a structured systematic review, as the topic was multi-faceted, the question could not be narrowly defined, and it was important to map all studies conducted and include all levels of evidence, all of which are key strengths of the scoping review approach.Reference Arksey and O'Malley 7 There are many different types of alternative EMS programs included in this body of literature, which spans over two decades, during which time EMS has changed significantly, all of which may affect the suitability of the outcome measures collected. These alternative EMS programs have often developed out of local needs in attempts to better serve their patient population with the resources that are available.Reference Eastwood, Morgans and Smith 32 While appropriate, this leads to difficulty in understanding what the findings mean in aggregate, and certainly prohibits quantitative pooling in a systematic review. This heterogeneity can also significantly limit the generalizability of the findings to contemporary EMS systems; however, the outcomes used can still be considered for use in modern research and quality projects. Some publications provided limited information on their EMS settings or programs.

Conclusion

In this broad scoping review on alternatives to traditional EMS dispatch and transport, numerous outcome measures used to measure and report on these interventions and programs were identified and catalogued. Researchers and program leaders should achieve consensus on the most important outcome measures to be used in future research studies, program evaluations and quality assessments of these programs.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Peter Rose, ACP, who assisted with the grey literature search, and to Fahd Al-Dhalaan, Dalhousie University medical student, who assisted with data abstraction.

Competing interests: The authors would like to declare funding information: Emergency Health Services provided funding for the MLIS candidate to design and conduct bibliographic searches. EHS Operations Management provided in-kind support.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/cem.2014.59