INTRODUCTION

Across Canada and the United States, an increasing number of children and youth seek care for mental health (MH) crises in the emergency department (ED).Reference Simon and Schoendorf1–Reference Baren, Mace and Hendry5 EDs are often the first point of contact between children, youth, their families, and the MH system,Reference Sadka6–9 where approximately 50% of children and youth in Ontario sought care for MH in the ED because they lacked an outpatient provider.Reference Gill, Saunders and Gandhi8, 9 To date, limited research has examined the clinical management and care received in the ED and the associated outcomes.Reference Hamm, Osmond and Curran10–Reference Grupp-Phelan, Mahajan and Foltin12 Models of care for pediatric MH emergencies are few,Reference Hamm, Osmond and Curran10, Reference Newton, Ali and Hamm11, Reference Leon, Cappelli and Ali13 clinical practice guidelines for general clinical management do not exist, and, subsequently, the range of emergency MH services that are provided during the visit varies considerably.Reference Leon, Cappelli and Ali13

The decision to admit or discharge a child following a MH crisis and the recommendations associated with this decision are of utmost importance. Most children and youth presenting to the ED with a MH emergency are discharged home.Reference Mapelli, Black and Doan4, Reference Santiago, Tunik and Foltin14–Reference Kennedy, Cloutier and Glennie19 Research suggests that 32% to 48% of youth do not receive discharge instructions,Reference Newton, Ali and Hamm11, Reference Cappelli, Glennie and Cloutier20 and between 21% and 46% of patients return to the ED after their initial visit for additional crisis care,Reference Newton, Ali and Johnson21–Reference Cloutier, Thibedeau and Barrowman24 which is not always due to increasing clinical acuity.Reference Yu, Rosychuk and Newton25 Furthermore, many discharged youth do not receive urgent outpatient MH care or physician-based outpatient care within 60 days following their ED visit.Reference Sobolewski, Richey and Kowatch23, Reference Bridge, Marcus and Olfson26 Among specific high-risk clinical presentations of suicidal behaviour (ideation, self-harm, or overdose), patients are 5.8 times at risk for suicide mortality after discharge compared to non-suicidal behaviour presentations.Reference Crandall, Fullerton-Gleason and Aguero27

Despite the commonality of discharge following ED pediatric MH care and the known importance of the recommendations that accompany this disposition decision, little is known about post discharge health care access. Objectives were to identify pediatric MH needs at the time of ED presentation, variation between sites in terms of patient needs, and the follow-up MH services accessed by children and their families.

METHODS

This prospective cohort study was conducted in three Canadian pediatric EDs and one general ED with a pediatric MH team, with a 1-month follow-up post discharge. The sites consisted of the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario (CHEO; Ottawa, ON), IWK Health Centre (IWK; Halifax, NS), Stollery Children’s Hospital (SCH; Edmonton, AB), and the Royal Alexandra Hospital (RAH; Edmonton, AB). The EDs differed on MH censuses (CHEO=1,512; IWK=853; SCH=431; RAH=953) and MH care providers (e.g., nurses, emergentologists, psychologists, social workers, psychiatrists). The study was conducted between June 2010 and September 2011. Research assistants (RAs) were available during weekday shifts, Monday to Friday, 0800 to 2300 hours, with some variability. Research ethics approval was received for all sites.

Participant population

Children and youth ages 6 to 18 years who presented to the ED with MH complaints (i.e., primary complaints identified by triage as MH [psychosocial, behavioural]) were approached for recruitment. Patients were excluded if they 1) did not have the capacity to consent; 2) presented with an overdose requiring medical intervention, or with severe self-harm (e.g., self-harm that required medical treatment), or referred for medical treatment and admitted directly to the hospital; and 3) triaged with Resuscitation (level 1) and Emergent (level 2) levels [REUSN (Resuscitation, Emergent, Semi-urgent, Urgent, Non-urgent) Triage Category; CHEO] or resuscitation or emergent levels (Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale [CTAS] scores 1 and 2, IWK, SCH, RAH). Patients were eligible once they were stabilized and were approached for the study at the discretion of the ED clinicians. Two disposition pathways were defined based on initial triage: 1) triaged to specialized MH services (SMHS; e.g., crisis worker, psychiatrist, psychologist) directly by the emergency triage nurse or referred by the ED physician; and 2) seen by the ED physician and then discharged to the community. Direction toward SMHS or the ED physician was determined by a need for medical attention, SMHS availability, and/or site resources.

MEASURES

A study RA obtained demographic information from the caregiver or patient, identified MH needs, and recorded discharge recommendations from the medical record (e.g., hospitalization, outpatient services, community services, family physician). At 1-month post-ED discharge, unaccompanied patients or caregivers who attended the ED were contacted by telephone for a follow-up interview. The interview was designed to elicit descriptions of MH service experiences (i.e., course of action, services obtained or booked, and community service satisfaction) and on satisfaction with ED care.

Mental health needs

RAs at each site were trained to observe the clinical assessment of the patient by the SMHS or ED physician and complete the Child and Adolescent Needs and Strengths-Mental Health (CANS-MH 3.0)Reference Lyons, Bisnaire and Greenham28 sections regarding MH and risky behaviours. The CANS-MH 3.0 tool integrates information concerning individual needs and strengths of children and youth with MH challenges. The tool is a communimetric measure,Reference Lyons29 where individual items use anchors that define levels of action: “0” – no evidence: no action needed; “1” – watchful waiting/prevention: need should be monitored, or efforts to prevent it from returning or worsening should be initiated; “2” – action: intervention required because the need is interfering with individual, family, or community functioning; “3” – immediate/intensive action: need is dangerous or disabling. The CANS-MH 3.0 is reliable at the item level and is unaffected by selecting a subset of target items.Reference Anderson, Lyons and Giles30 The tool has demonstrated validity,Reference Anderson, Lyons and Giles30 and total scores have reliably distinguished the level of care received.Reference Lyons31

Behaviour problems

Caregivers completed the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL)Reference Achenbach and Rescorla32 for youth ages 6 to 18 to evaluate behavioural problems and social competencies. A standardized score of≥64 indicates concern in the wider areas of internalizing (e.g., anxiety, depression, social withdrawal), externalizing (e.g., conduct, aggression, rule-breaking), and total problems, whereas≥70 indicates areas of clinical concern for specific psychiatric conditions found in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders IV (e.g., anxiety, conduct). Psychometric properties of this instrument are well-established.Reference Achenbach and Rescorla32

Satisfaction

The Client Satisfaction Questionnaire (CSQ-8©)Reference Attkisson and Greenfield33 was administered at the baseline ED visit and during the 1-month follow-up telephone interview. The CSQ-8 has eight questions designed as a global measure of a patient’s satisfaction of their ED visit. Total scores range from 8 to 32; higher scores indicate greater satisfaction with ED services. This tool has established psychometrics and has been used extensively in evaluation studies.Reference Attkisson and Zwick34, Reference LeVois, Nguyen and Attkisson35

Mental health services use

The first eight questions of the Services for Children and Adolescents-Parent Interview (SCA-PI)Reference Jensen, Eaton Hoagwood and Roper36 were asked during the follow-up interview to assess number and type of MH services received within the 1-month post-ED visit. The SCA-PI has good reliabilityReference Hoagwood, Jensen and Arnold37 and face validity with appropriate differences in service reporting.Reference Jensen, Eaton Hoagwood and Roper36

Recommendations

Youth or caregivers were asked open-ended questions to elicit ratings of recommendations received during the ED visit. Individuals were asked the following questions: Were you given any recommendations for follow-up care? How were the recommendations given to you? What were the recommendations? Respondents could provide up to four recommendations and rate each as to its usefulness (1=“not at all” to 4=“very”), practicality (1=“definitely not” to 4=“very”), openness to the recommendation (1=“definitely open” to 4=“definitely not open” [reverse scored]), whether action was taken related to recommendation (1=yes, 2=no), whether the recommendation was obtained (1=yes, 2=no), and waitlist status of the recommendation (1=yes, 2=no). Four-point scale scores were dichotomized (scales of 1 or 2 were categorized as negative ratings [no], and 3 or 4 were categorized as positive ratings [yes]).

STATISTICAL AND QUALITATIVE ANALYSES

The data were analysed with SPSS version 24.0.38 Frequencies described the data by site. An analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted to compare the means (Ms) and standard deviations (SDs), which described the differences in participant age among sites. The equality of proportions across sites was assessed by Fisher’s exact tests on non-missing data. Crosstabs were used to examine the frequencies of follow-up recommendations between sites and for those who were admitted versus discharged with identified needs in the clinical ranges on the CBCL and CANS-MH 3.0. A paired samples t-test was used to examine change in mean differences of satisfaction over a 1-month period following ED discharge. All tests were two-tailed and a p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Qualitative data on care recommendations were synthesized by finding common recommendation types, and multiple response crosstabs were used.

RESULTS

Sample demographics

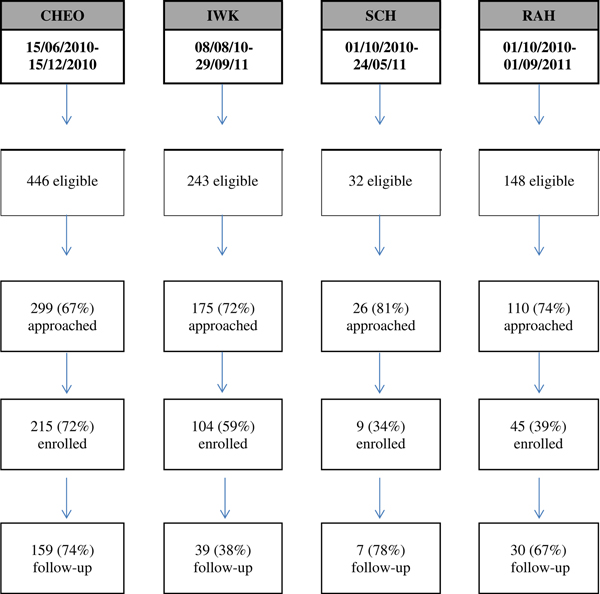

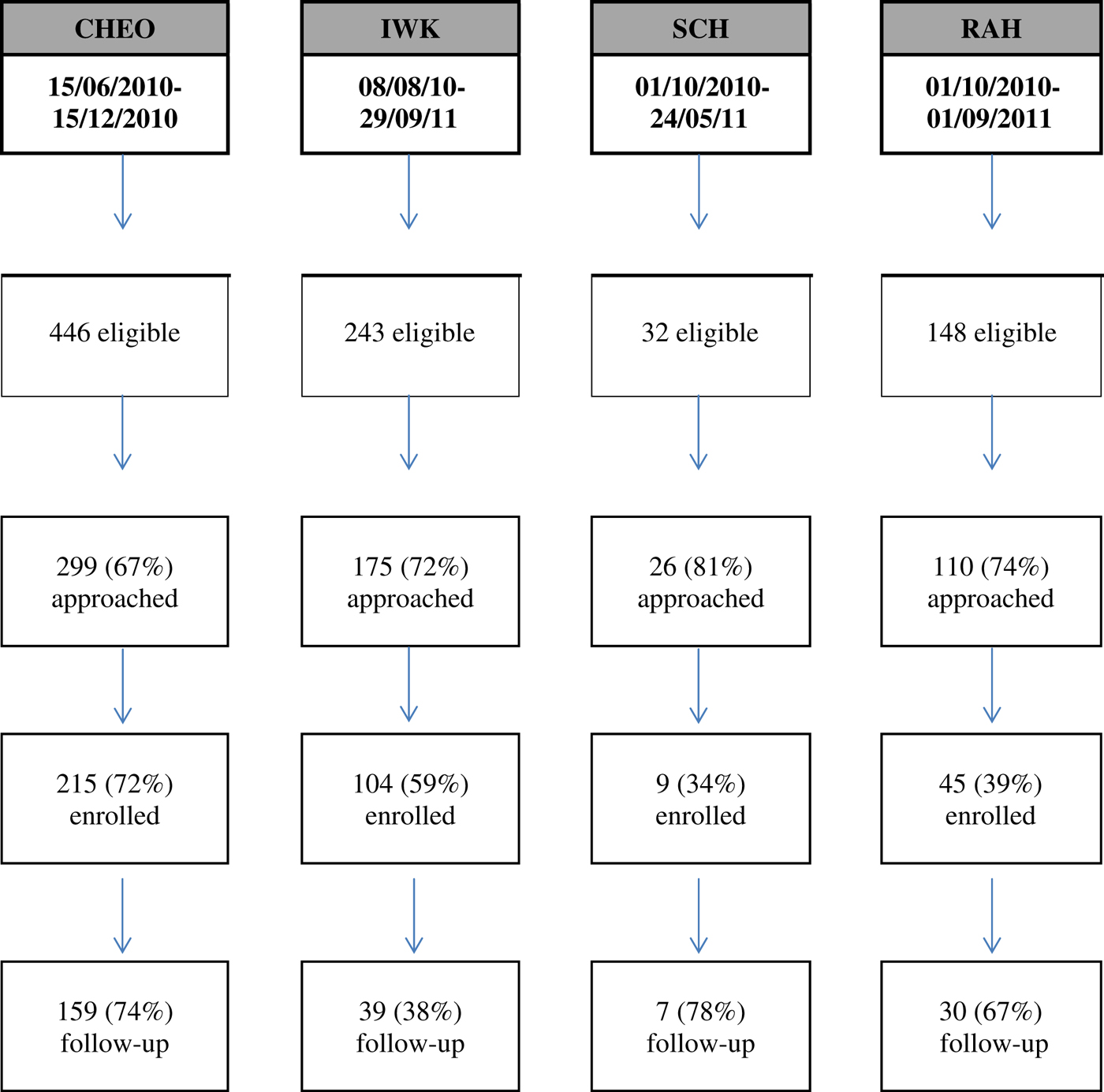

A total of 373 patients (M age=15.1 years; SD=1.51; 61% female) consented to participate (Table 1). Figure 1 illustrates the breakdown of presentations, uptake and attrition rates across sites. At the time of the ED visit, 63.5% had existing MH resources, 47.4% were taking psychotropic medication, and 88.4% were attending school. One quarter (24.2%) were actively involved in the child welfare system. Significant differences among sites were found in the proportion of those involved in the child welfare system, on an assessment order, and those currently attending school (see Table 1).

Figure 1 Flow diagram showing participant recruitment and retention rates per site. CHEO=Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario; IWK=IWK Health Centre; SCH=Stollery Children’s Hospital; RAH=Royal Alexandra Hospital.

Table 1 Demographics and clinical descriptions collected in the ED by site, n (%)

Note: Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used for age. Fisher’s exact test was used to compare the proportion of responses by site.

CHEO=Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario; IWK=IWK Health Centre; RAH=Royal Alexandra Hospital; SCH=Stollery Children’s Hospital; SD=standard deviation.

Clinical demographics

The top three areas of need requiring action (item score of 2 or 3 on the CANS-MH 3.0) were mood, suicide risk, and parent-child relational problems (Table 2). A higher proportion of psychiatric admissions occurred when needs were identified as requiring immediate action in the areas of psychosis, mood, adjustment to trauma, and suicide risk. Significant differences among actionable ratings were found among sites for a number of symptoms and risky behaviours.

Table 2 Mental health needs (using the CANS MH 3.0) rated as actionable by disposition, site, and total sample, n (%)

CHEO=Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario; IWK=IWK Health Centre; RAH=Royal Alexandra Hospital; SCH=Stollery Children’s Hospital.

Note: Fisher’s exact test used to compare the proportion of responses by site, actionable CANS items were combined as 2 (interfering with functioning) or 3(dangerous or disabling); N=371 for admit and discharge.

Caregiver CBCL ratings of their child’s behaviour (Table 3) indicated that 85.5% were at a level of clinical concern for internalizing behaviour and 60.2% for externalizing behaviour. The majority of patients were in the clinical range for affect problems, followed by anxiety, somatic, conduct, oppositional, and attention problems. A larger proportion of children were admitted to hospital when CBCL internalizing scores, total scores, and affect were in the clinical range. Those with conduct problems in the clinical range had fewer admissions than those without.

Table 3 Percentage of patients identified with the CBCL as having mental health concerns in the clinical range by total sample, disposition, and by site, n (%)

CBCL=Child Behavior Checklist; CHEO=Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario; IWK=IWK Health Centre; RAH=Royal Alexandra Hospital; SCH=Stollery Children’s Hospital.

* Clinical range for Total, Internalizing, and Externalizing scales score≥64.

† Clinical range for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) scales≥70. Note: Fisher’s exact test was used to compare the proportion of responses by site. N Total=249; Total missing 33.2% (N=124/373); CHEO 27% (N=58/215); IWK 55.7% (58/104); SCH 11.1% (N=1/9); RAH 15.6% (N=7/45). Completed CBCL (N=247) for admit and discharge.

PATIENT MANAGEMENT WITHIN THE ED

During the ED visit, patients were seen by a crisis worker (73.2%; n=271/370), ED physician (11.4%; n=42/370), ED physician and an MH professional (8.9%; n=33/370), psychiatrist (4.9%; n=18/370), psychiatric nurse (1.4%; n=5/370), and psychologist (0.3%; n=1/370). Acute medical care (e.g., suturing, medical observation, treatment for overdose) and MH care were required for 21.6% (n=80/370) of patients. A psychiatrist was consulted for 40.9% of patients (n=128/313) by phone (20.1%; n=63/313) or in person (20.8%; n=65/313). Lastly, 19.4% (n=72/371) were admitted to inpatient psychiatric care for stabilization.

FOLLOW-UP SERVICES

At 1-month follow-up, 84.3% of patients had received follow-up services, which included any of the following: individual therapy, group therapy, family therapy, school services, overnight treatment, or parent counselling (Table 4). Excluding school and parent counselling, 69.9% patients received either individual, group, in-home, family, or overnight treatment. The most common follow-up service recommendations were secondary care providers (e.g., psychologist, psychiatrist) followed by home/community care, provision of information, primary care, and tertiary care.

Table 4 Follow-up SCA-PI mental health use at 1-month post-ED and follow-up care recommendations by site, n (%)

CHEO=Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario; ED=emergency department; IWK=IWK Health Centre; RAH=Royal Alexandra Hospital; SCH=Stollery Children’s Hospital.

Note: A valid percent was reported for percentages in the table; percentages may not add up to 100% due to rounding. Fisher’s exact test was used to compare the proportion of responses by site. Statistical comparisons by site were not reported because class of care was based on multiple responses.

* Includes psychologists, psychiatrists, counsellors, and social workers.

† Includes pediatricians, family doctors, and nurses.

‡ Examples: psychiatrist, psychologist, hospital outpatient clinics, partial hospitalization.

§ Examples: crisis lines, drug rehabilitation services in community, community mental health counselling/support.

¶ Examples: workbooks, safety plans, websites, advice, behavioural strategies.

** Examples: family doctors, health clinics.

†† Examples: hospitalization other than admission from emergency department.

HEALTH CARE SATISFACTION

At 1-month follow-up, satisfaction scores across sites increased for 30.1% (n=46/153), remained the same for 11.1% (n=17/153), and decreased for 58.8% (n=90/153) of youth and caregivers. Overall, ED satisfaction was high (M=26.5; SD=5.5) but dropped slightly (M=24.2; SD=6.5) at follow-up (Mdiff=2.3, SD=5.0, p<0.001). Satisfaction with the ED visit was higher when patients were connected with any recommendation at 1-month post-ED visit (M=25.9; SD=5.3), than those who were not (M=21.2, SD=7.2), p<0.001, Mdiff=4.72, p=0.000, and when patients were admitted (n=43; M=27.4; SD=5.0) versus discharged (n=183; M=23.7; SD=6.4), Mdiff=3.70, p=0.000. No significant differences in mean satisfaction were found at 1-month post-ED visit between those already connected to services at the time of the ED visit (M=23.7; SD=6.5) and those without services (M=25.2; SD=6.0).

RECOMMENDATIONS

Open-ended discharge recommendations were provided and rated by 12.8% of youth (n=30/234) and 87.2% of caregivers (n=204/234). Recommendations were categorized by level of care (Table 5). Secondary care recommendations were rated as most useful and practical, caregivers and youth were more open to receiving secondary care, and they were more likely to take action and obtain the secondary care recommendation. No significant difference emerged in obtaining any recommended MH service (excluding information strategies) for those already connected with professional services at the time of the ED visit (73.5%, n=75/102), versus those without (62.3%, n=43/69, 95% confidence interval [CI]=– 3.7 to 26.2).

Table 5 Comparison of favoured recommended service ratings by level of care after 1 month follow-up, n (%)

* Number of respondents indicating “Yes” to a recommendation.

† Number of total respondents; percentages and totals vary based upon multiple responses indicating “Yes” for each individual. Percentage calculations of service ratings were based upon positive ratings of “Yes.”

‡ Examples: psychiatrist, psychologist, hospital outpatient clinics, partial hospitalization.

§ Examples: crisis lines, drug rehabilitation services in community, community mental health counselling/support.

¶ Examples: workbooks, safety plans, websites, advice, behavioural strategies.

** Examples: family physicians, health clinics.

†† Examples: hospitalization other than admission from emergency department.

DISCUSSION

Current literature identifies the ED as the first point of contact for many patients and the MH system.Reference Sadka6–9 However, this study demonstrated that the majority (63%) of patients presenting to the four ED sites were in fact connected to existing resources. These results are consistent with recent U.S. literature where patients connected to services ranged between 61% and 83%.Reference Sobolewski, Richey and Kowatch23, Reference Frosch, McCulloch and Yoon39–Reference Frosch, DosReis and Maloney40 Overall, it appears that the ED plays an important role in the continuum of care for pediatric patients and their caregivers, despite accessing other MH services.

Results from this study point to several areas of patient need, including affect and emotional regulation, suicide risk, and parent-child relationship problems. The parent-child relationship has been scarcely investigated or considered in previous ED researchReference Leon, Cloutier and Polihronis41 and highlights the need for relational support for families in times of crisis. Given that the ED’s role is to provide immediate assistance in an emergency, to address non-urgent patient needs, pathways from the ED to appropriate outpatient and community MH services should be clearly developed and evaluated.Reference Jabbour, Reid and Polihronis42 ED clinicians can play an important role in educating patients and their caregivers about accessing appropriate resources to best meet their MH needs, including crisis lines, MH walk-in clinics, and requesting urgent follow-up with existing MH providers. Tools to quickly and easily access information about local resources should also be available in the ED so that providers can direct patients to appropriate community resources.Reference Cappelli, Zemek and Polihronis43

Variation between the study EDs, in terms of who uses them and why, points to the necessity of providing a variety of resources to meet variation in population and patient need. Clinical management across sites indicated significant differences for medical care and psychiatric consultations. These differences are consistent with previous Canadian literatureReference Newton, Ali and Hamm11, Reference Leon, Cappelli and Ali13 and reinforce the need for national policies to guide service development, evaluation, and to promote resource allocation.Reference Shatkin and Belfer44 Our study adds a unique perspective by including caregiver ratings of child/youth needs, as solely discharge diagnoses at the ED visit and presenting complaints have been examined previously.Reference Lehman and Zastowny45 Including both caregiver and clinician perspectives as part of standard care can indicate areas of agreement and discrepancy and help the clinician to tailor services and recommendations to meet their patient needs. Allowing caregivers to voice their concerns and expectations may facilitate identifying precipitating stressors related to the ED presentation and improve family-centred care and intervention.Reference Cloutier, Kennedy and Maysenhoelder7

In this study, the majority of follow-up resources recommended at discharge were secondary care and home/community care. Patients and caregivers perceived these recommendations as most useful, practical, and obtainable as opposed to primary and tertiary care. To our knowledge, this is the only study to comprehensively investigate discharge planning in a non-suicide specific sample from the perspective of the caregiver. At 1-month follow-up, almost three quarters of patients reported having received some form of MH-specific post-ED care. Slightly lower rates have been reported by recent U.S. studies, where two thirds of psychiatric and suicidal youth indicated post-ED connections to community services.Reference Sobolewski, Richey and Kowatch23, Reference Frosch, DosReis and Maloney40 It remains unclear in these studies, however, what percentage of pediatric patients who presented to the ED with no prior MH connections were successful at obtaining services post-ED visit. Frosh and colleaguesReference Frosch, DosReis and Maloney40 have reported that the likelihood of being connected to outpatient services was nearly five times higher at a second ED visit if the youth was already connected at the index visit. This would imply that it may be difficult to initially gain access to services, but, once connected, rates with outpatient providers remain high. It also suggests that the ED may have a useful role at identifying and facilitating initial contact with services in the hopes of improving access to care and decreasing return visits to the ED.

There is little research exploring patient satisfaction with MH services received in the ED. Overall satisfaction ratings obtained in this study are consistent with existing research indicating a high rate of patient satisfaction.Reference Lehman and Zastowny45, Reference Lebow46 In this study, patients were more satisfied with their ED visit when they received services (e.g., if they were admitted and if they received any recommended service at 1-month post-ED visit). Previous research has identified several health service variables correlated with satisfaction, including perceived choice in service seeking, expectations about services, duration of treatment, provision of information regarding services, and service site.Reference Garland, Aarons and Saltzman47, Reference O’Regan and Ryan48 Despite a statistically significant drop in total satisfaction ratings at 1-month follow-up, the mean drop in ratings was modest and remained in the satisfied range. Changes in scores at follow-up may have been influenced by experiences with obtaining post-ED care, but we did not test this hypothesis.

There are several limitations to this study. There were differences in the percentage of children/youth enrolled across study sites and in follow-up rates. The smaller number of children/youth approached at SCH was anticipated, as current practice at the time was to send patients to the RAH, which had in-house pediatric MH resources. Thus, both sites were included to increase the representativeness of the target population. However, the low participation rates at both the SCH and IWK, and modest participation rates at other sites, introduce the possibility of selection bias. Furthermore, low follow-up rates at IWK may reflect attrition bias; however, this bias was unavoidable due to IWK site research ethics board requirements that limited the number of attempted telephone contacts for each participant. Future studies should also examine satisfaction related to repeat ED visits and the longitudinal MH care access trajectories past 1 month. Ratings may have suffered from recall bias or social desirability bias. We reduced the risk of social desirability bias by having RAs indicate that they were not part of the ED clinical team and reiterated that survey responses were confidential and would not be shared with the ED staff or physicians.

CONCLUSION

Pediatric MH presentations to the ED had significant clinical morbidity. The majority of patients presenting to the ED were connected with services, satisfied with their ED visit, and able to access follow-up care. Clinical trends pointed to high area needs – affect and emotional regulation, suicide risk, and parent-child relations – for ED clinical management. Furthermore, differences in clinical management across study sites point to an important need to standardize clinical approaches. Two areas that can help with clinical management of this patient population include 1) clinical pathways using a set of evidence-based standards to facilitate the management and transition of care from EDs to outpatient and community resourcesReference Jabbour, Reid and Polihronis42, Reference Barwick, Boydell and Horning49, 50; and 2) an integrated system linking EDs, primary care, and community MH agencies.Reference Cappelli and Leon51 Future research should investigate the barriers to community care that encourage patients to continue using the ED as a point of access to MH care.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Rebecca Gokiert, Patrick McGrath, Doug Sinclair, and Elizabeth Glennie for their contribution to this study. This work was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (grant #103646), The RBC Foundation, and the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario Foundation. Dr. Newton is salary supported as a CIHR New Investigator. Dr. Rosychuk was salary supported as an Alberta Innovates – Health Solutions (AI-HS, Edmonton) Health Scholar during the work.

Competing interests

None declared.