Clinician's Capsule

What is known about the topic?

Fentanyl and ultra-potent opioid prevalence are increasing in North America; however, optimal naloxone dosing for toxicity reversal remains unknown.

What did this study ask?

What is the relationship between naloxone dose (initial and cumulative) and toxicity reversal and adverse events in suspected fentanyl and ultra-potent opioid toxicity?

What did this study find?

Higher initial and cumulative naloxone doses have been used and may be necessary for adequate toxicity reversal.

Why does this study matter to clinicians?

Naloxone titration to response may be needed; however, association of dose with adverse events remains unanswered in this population.

INTRODUCTION

The ongoing opioid epidemic in North America has decreased life expectancy in the United States and Canada.1–Reference Allen8 National strategies aim to expand naloxone access to prevent opioid-related deaths.9,10 Since 2013, fentanyl and ultra-potent opioids, (≥50–100 times more potent than morphine), are increasingly prevalent in North America.11–15 In 2015, the United States issued a nationwide alert on fentanyl, yet overdose deaths from fentanyl/ultra-potent opioids doubled from 2015–2016.11,16 British Columbia, the province at the epicenter of the Canadian epidemic, declared “fentanyl emergence” in the illicit drug supply in 2015 due to increased fentanyl detection in urine drug screens among people unaware of their fentanyl exposure.17,Reference Amlani, McKee, Khamis, Raghukumar, Tsang and Buxton18 By 2018, fentanyl/ultra-potent opioids were detected in 85% of illicit overdoses in British Columbia.19

Naloxone is a competitive opioid antagonist that reverses opioid toxicity.Reference Trescot, Datta, Lee and Hansen20–Reference Boyer22 However, it may have harmful effects in opioid-tolerant patients, if administered in higher doses than required. These include withdrawal (e.g., agitation, diaphoresis, vomiting) and other serious effects (e.g., pulmonary edema, seizures, dysrhythmias).Reference Buajordet, Naess, Jacobsen and Brors23–Reference Andree30 The optimal dose likely differs by opioid type.Reference van Dorp, Yassen and Dahan24,Reference Evans, Hogg, Lunn and Rosen31 Emerging evidence suggests that higher doses may be required in fentanyl/ultra-potent opioid toxicity.Reference Schumann, Erickson, Thompson, Zautcke and Denton32,Reference Sutter, Gerona and Davis33 Despite an urgent need to update current guidelines to reflect changing epidemiology, the optimal naloxone dosing for fentanyl/ultra-potent opioid overdoses remains unknown.Reference Lavonas, Drennan and Gabrielli34,Reference Connors and Nelson35 Existing reviews on naloxone dosing have not specifically examined data from presumed fentanyl/ultra-potent opioid overdoses, and, therefore, are not generalizable to jurisdictions with high fentanyl/ultra-potent opioid prevalence.Reference Boyer22,Reference Chou, Korthuis and McCarty36–Reference Clarke, Dargan and Jones38

Our main objective was to synthesize evidence on the relationship between initial naloxone dose and toxicity reversal among patients with undifferentiated and presumed fentanyl/ultra-potent opioid toxicity. Secondary objectives were to assess the relationship between cumulative naloxone dose and toxicity reversal, and between dose and adverse events.

METHODS

This systematic review was registered in PROSPERO (CRD42018096612), and follows Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines.Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman39 Details are available in a submitted protocol.

Eligibility criteria

We included studies examining people >12 years who received naloxone (any route, lay or health care responders) for toxicity from nonmedical opioid use. We chose this age cutoff because we hypothesized that adolescents respond similarly to adults. No comparator group was necessary. Included studies needed to document dose (initial and/or cumulative), and response and/or adverse events.

We included interventional and observational studies, and case reports/series to capture the most up-to-date evidence, given the novelty of fentanyl/ultra-potent opioid exposures, and the paucity of formal studies.

Data sources and searches

A professional librarian developed a primary search strategy in Embase using EMTREE subject headings and keywords from >90 relevant papers. We included all pertinent ultra-potent opioid indexing terms and synonyms. Our search included concepts naloxone AND drug overdose AND (adverse effects OR emergency care OR drug administration), and concepts naloxone AND (dosage OR administration OR adverse drug effects OR ultra-potent opioids). We searched for systematic reviews to October 3, 2018. We adapted subsequent searches to MEDLINE(Ovid), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, and Science Citation Index (Web of Science). We applied searches from 1972 to 2018 and limited to human studies with no language restrictions during title/abstract screening. Our full text review included relevant English citations, and French and German articles from Embase and MEDLINE(Ovid).

To identify grey literature, we searched Google using terms “naloxone,” “opioid,” “fentanyl,” and “ultra-potent opioid.” We searched websites and conference proceedings of professional toxicology organizations, harm reduction initiatives, opioid overdose guidelines, reference lists, and table of contents of prespecified journals.

Study selection

Two investigators assessed abstracts and full-text articles independently and in duplicate using a pilot-tested standardized form. We resolved disagreements through discussion or arbitration.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Two reviewers extracted data independently and in duplicate. Where reported, we extracted information on proportion of patients responding to specified doses. We attempted to email studies’ authors twice for missing information.

Two independent investigators appraised English studies for risk of bias using an adapted Downs & Black tool for observational and case studies/seriesReference Downs and Black40 and Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool for randomized controlled trials.41 One reviewer assessed French and German studies for inclusion, risk of bias, and extracted data.

Definitions

Dosing

We defined initial dose as the first naloxone dose administered. We stratified initial doses as ≤0.4 mg (low) and >0.4 mg (high).

We defined cumulative dose as the sum of naloxone bolus doses. We excluded infusions, which are typically initiated after reversal to maintain ventilation and level of consciousness.

Response

We defined response to an initial dose if no additional doses were administered and patients remained alive. Due to inconsistent reporting, we were unable to specify a timeframe for response. We defined response to a cumulative dose if the patient remained alive after the overdose, regardless of additional treatments (e.g., infusions, intubation, other resuscitation).

Data synthesis and analysis

Due to high clinical/methodological heterogeneity, we did not meta-analyze results and instead synthesized them descriptively.

For each study, we abstracted total subjects, and number responding and/or experiencing an adverse event. If results were presented by dose received, we abstracted information for each dose level, and proportion responding. We performed subgroup analyses by confirmed or suspected opioid, study year, region, and location of administration (i.e., community, prehospital, or emergency department <ED>).

For studies reporting response after presumed fentanyl/ultra-potent opioid toxicity, we plotted cumulative response probability against cumulative dose to identify variability in this association, and to assess whether we could recommend a uniform naloxone dose.

RESULTS

Study characteristics

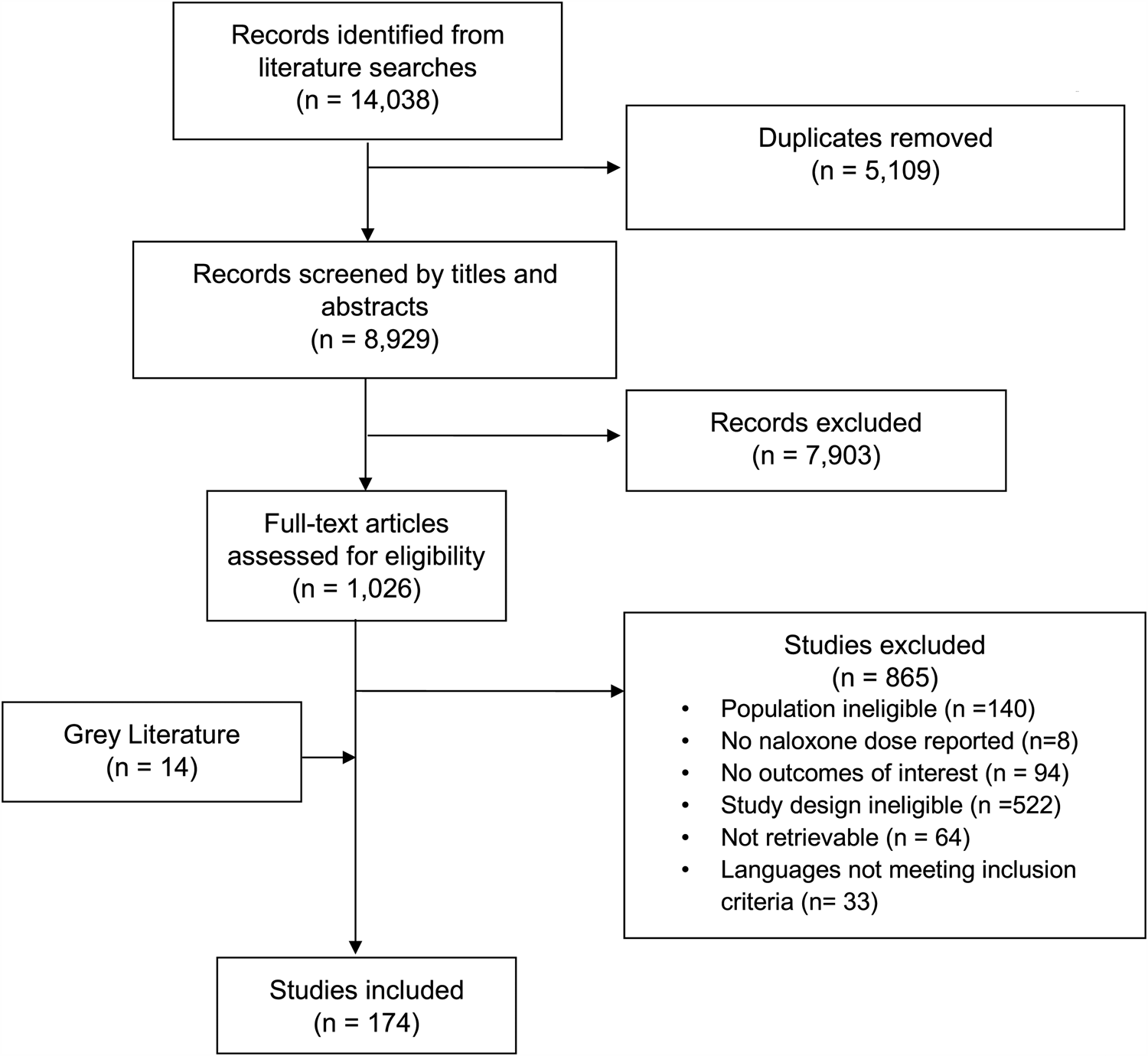

We identified 14,038 citations; 174 met inclusion criteria (Figure 1). There were 110 case reports/series, 57 observational studies, 6 randomized controlled trials, and 1 nonrandomized controlled trial. Publication dates ranged from 1972 to 2018, with 45 studies published after 2015, when North American sites started reporting increasing fentanyl/ultra-potent opioid prevalence.16,17 Included studies reported on 26,660 cases of opioid intoxication treated with naloxone. Geographically, 107 studies (n = 16,574) were completed in North America and 49 in Europe (n = 8,066; Supplemental Online Appendix Table 1).

Figure 1. Evidence search and selection.

Median age was 35 years (interquartile interval [IQI], 25–41); 74% were male. Forty studies reported heroin exposure, and 25 reported presumed fentanyl/ultra-potent opioid toxicity. Naloxone administration occurred in the community or prehospital in 55 studies, and in ED or hospital in 57 studies. Studies most commonly reported intravenous (n = 119 [60%]), then intramuscular/subcutaneous (n = 48 [24%]), and intranasal (n = 24 [12%]) administration. Many reported multiple routes.

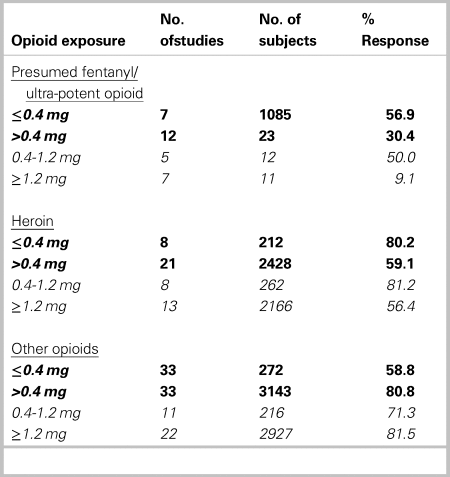

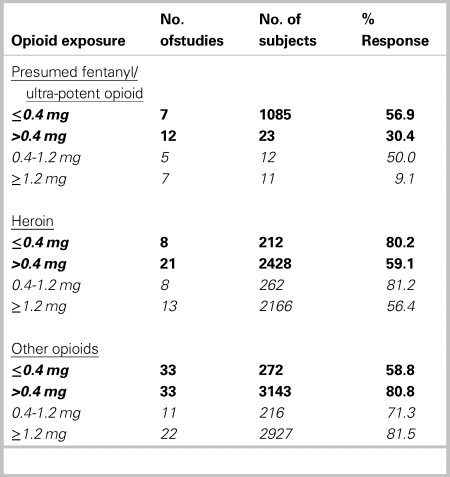

Initial naloxone dosing

Among studies reporting proportional response to initial naloxone dose, 60.3% (n = 48) responded in studies reporting doses ≤0.4 mg, and 70.1% (n = 66) in studies reporting initial doses >0.4 mg. Some of these studies reported providing initial doses both ≤0.4 mg and >0.4 mg to different groups. Where studies reported a low initial dose, 56.9% (617/1,085) of patients with presumed fentanyl/ultra-potent opioid exposure responded, v. 80.2% (170/212) of patients exposed to heroin. Where studies reported a high initial dose, 30.4% (7/23) of patients with presumed fentanyl/ultra-potent opioid exposure responded, compared with 59.1% (1,434/2,428) of patients exposed to heroin (Table 1). When we examined initial doses ≥1.2 mg, 9.1% (1/11) and 56.4% (1,221/2,166) of patients with presumed fentanyl/ultra-potent opioid v. heroin exposure responded, respectively (Table 1). Among patients administered a higher initial dose, response rates were similar for different routes of administration. Initial doses administered increased over time. When studies were compared by publication year, fewer patients responded to low doses in more recent studies (72.1% [n = 36] in studies before 2015, v. 56.6% [n = 12] in studies in 2015 and later).

Table 1. Proportion of patient response to initial naloxone dose, by opioid exposure*

The boldfaced data are the main dosing categories. The non-boldfaced data (0.4–1.2 mg, and ≥ 1.2 mg) refer to subcategories of the main category >0.4 mg.

Our subgroup analysis by location indicated lower responses to any initial dose administered in EDs (42.9% [70/163]) v. community (60.0% [945/1574]) or prehospital (68.7% [2983/4343]).

Cumulative naloxone dosing

Seventy-five studies reported cumulative naloxone dose and proportion responding. Cumulative doses ranged from 0.04 mg to 44 mg among responders. Median cumulative dose among responders was higher for patients with presumed fentanyl/ultra-potent opioid exposure than heroin/other opioids in North America. Furthermore, median cumulative doses for all opioids increased in nearly all regions over time (Table 2).

Table 2. Cumulative naloxone dose among responders by opioid exposure, region and publication year

By location, we found lower median cumulative doses in EDs (0.4 mg [IQI 0.08–1.6 mg]), v. community (0.8 mg [IQI 0.2–1.6 mg]) or prehospital (2.0 mg [IQI 2.0–2.0 mg]).

One epidemiological study42 described naloxone doses required to reverse overdoses in Pittsburgh from 2013 to 2016 (n = 225, 165, 236, 446 per year), over which time there was increasing fentanyl prevalence in overdose deaths (3.5%, 25.0%, 32.8%, and 68.7%).42 We generated annual dose-response curves using the 4 study years: a total dose of 0.8 mg generated 89% reversal, and 1.6 mg achieved 100% reversal. Annual dose-response curves were similar (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Cumulative dose-response curve for studies reporting presumed fentanyl/ultra-potent opioid exposures.

We combined data from remaining observational and case studies/series reporting presumed fentanyl/ultra-potent opioid toxicity in another dose-response curve (combined n = 182). This indicated marked variability in cumulative dosing among patients responding, and higher overall doses than Bell42: 0.8 mg generated 11% reversal, and 4 mg achieved 97% cumulative reversal (Figure 2).

Adverse effects

Adverse events reporting was inconsistent. Studies rarely specified events of interest a priori, and few reported dose received by individual patients experiencing adverse events. Therefore, we could not associate event occurrence with dose. Among 86 studies reporting adverse events, 41 described withdrawal, 17 pulmonary edema, and 11 seizures. It was often unclear if events were due to naloxone, or to the overdose. Among studies reporting adverse events, 11% (n = 490/4414) and 1% (n = 52/4414) of participants experienced withdrawal and pulmonary edema, respectively.

DISCUSSION

Interpretation of findings

We aimed to synthesize evidence on naloxone dosing and reversal in undifferentiated and presumed fentanyl/ultra-potent opioid toxicity, given the urgent need to expand naloxone use to reduce opioid-related deaths. Our review suggests that lay and health care providers are using higher initial doses, and in some cases higher cumulative doses to reverse presumed fentanyl/ultra-potent opioid toxicity, v. other opioids. Fewer patients responded to both low and high initial doses in presumed fentanyl/ultra-potent opioid overdoses v. heroin. In our analysis of cumulative dosing among patients responding, median doses for presumed fentanyl/ultra-potent opioid exposures were higher than for heroin/other opioids in North America, and increased over time. Our dose-response analysis indicated wide variability, and that a 4 mg cumulative dose correlated with 97% reversal of presumed fentanyl/ultra-potent opioid toxicity.

Importantly, we evaluated response among noncomparator studies. Therefore, response rates likely reflected differences among baseline populations (e.g., individual tolerance, co-morbidity), illness severity, or intoxicating opioid(s) (e.g., type, dose, route, potency). Lower response rates observed for higher v. lower initial doses in both presumed fentanyl/ultra-potent opioid and heroin exposures may be due to higher doses administered to patients with more severe toxicity (e.g., severe respiratory depression, or greater intoxicating dose). Similarly, lower responses to naloxone administered in EDs v. community/prehospital likely reflects that patients with more severe presentations are more likely transported to EDs. Our observations may also reflect provider behavior or clinical practice/protocols favoring higher doses over time and/or in North America. Alternatively, our findings may indicate that higher doses were required to reverse toxicity in settings with higher fentanyl/ultra-potent opioid prevalence (e.g., North America v. Europe/other regions).43,44

Our finding of lower median cumulative doses in ED v. community/prehospital settings may reflect different dosing protocols or administration routes (e.g., intranasal v. intravenous). Higher variability in cumulative doses in EDs likely indicates less protocol standardization compared with community/prehospital.

Strengths and limitations

This study is the most comprehensive systematic review to-date on naloxone dosing and the first to focus specifically on presumed fentanyl/ultra-potent opioid exposure. Compared with previous reviews, we have intentionally included nontraditional evidence sources (case reports/series) to capture recent fentanyl/ultra-potent opioid studies and ensure that our synthesis can inform urgently needed dosing protocols in areas with high fentanyl/ultra-potent opioid prevalence.

Our study is limited by inconsistent reporting. The specific rationale for initial and subsequent naloxone doses or routes were rarely provided. Therefore, we could not determine whether doses administered were necessary for reversal or driven by clinical practice/protocols. Parameters defining response were rarely outlined a priori, and timeframes were seldom clear. We therefore applied a simplified response definition (no additional doses, and patient remained alive) that we could uniformly apply. However, our definition may have misclassified patients who did not respond to a first dose, but whose ventilation was supported (e.g., intubation/noninvasive ventilation), who were administered additional dose(s) prematurely, or who initially responded, but required additional doses due to the intoxicating opioid's half-life.

Inconsistent reporting precluded us from adequately controlling for confounders (e.g., severity of toxicity) in our outcomes analysis. Additionally, our subgroup analyses of specific opioid exposures (e.g., fentanyl/ultra-potent opioids) relied on authors’ classifications (suspected or confirmed). We likely missed or misclassified cases where the specific opioid type was unknown or unsuspected.

Our subgroup analysis based on location is limited because most studies reported multiple settings and, therefore, were not included. Furthermore, due to small denominators, we could not stratify results by presumed opioid exposure and specific dose administered.

Due to limited adverse events reporting, we were unable to summarize evidence regarding association of dose with adverse events. This prevents us from recommending dose and titration strategies that would maximize effectiveness while avoiding adverse events. Nonetheless, our finding that 11% of patients experienced withdrawal and 1% experienced pulmonary edema where reported indicates that these events are not rare and require specific consideration in future studies. Our findings align with existing reported rates of approximately 10–20% for minor events, and 1% for serious/life-threatening events.Reference Buajordet, Naess, Jacobsen and Brors23,Reference van Dorp, Yassen and Dahan24,Reference Chou, Korthuis and McCarty36

Finally, our systematic review is limited by overall poor study quality. We deliberately decided to include case studies/reports to ensure comprehensiveness. While this gives our study breadth, our results are limited by selection bias in these studies.

Clinical and research implications

Clinically, our results indicate that higher naloxone doses have been used in presumed fentanyl/ultra-potent opioid overdoses, suggesting a need to titrate naloxone to response. However, given the lack of high-quality comparative studies, we have not answered whether higher naloxone doses are effective and safe. Therefore, our results do not support changing current standard of practice, where health care providers administer an initial naloxone dose, concurrently support ventilation, and provide additional doses as needed. Our results have important implications in bystander settings where titrating naloxone to effect is limited by amount available to lay responders. Jurisdictions should carefully consider amount of naloxone available in take-home kits, although limitations of available evidence prevent us from recommending a specific dose. Current take-home naloxone kits in British Columbia contain three 0.4-mg doses. Instructions direct bystanders to provide ventilations, and administer additional doses in 3–5 minutes if no response (or sooner if rigidity). We recommend that other jurisdictions with increasing fentanyl/ultra-potent opioid prevalence consider similar approaches.

Our results should inform robust comparator studies evaluating different dosing strategies. High-quality prospective studies are needed to compare effectiveness and safety of low v. high initial and cumulative doses in this new fentanyl/ultra-potent opioid era. Future studies should analyze primary data from prehospital (ambulance), bystander, and ED settings to evaluate different dosing strategies. Additionally, our review highlights a need to standardize response definitions. Clearly time-stamped vital signs and level of consciousness, before and after naloxone administration, would assist our understanding of clinical response to doses provided. Additionally, robust outcome measures would help to advance this field, by guiding future data collection, standardized registries, and allowing reliable analyses of pooled results in future systematic reviews.

CONCLUSION

In summary, in opioid toxicity due to presumed fentanyl/ultra-potent opioid exposure v. other opioids, higher initial doses, and in some cases higher cumulative naloxone doses have been used by providers to achieve adequate reversal. Due to limitations of the available data, the relationship between naloxone dose and adverse events could not be answered.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the Centre for Clinical Epidemiology and Evaluation for providing space and in-kind support for this research.

Supplemental material

The supplemental material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/cem.2019.471.

Financial support

This project was funded by a grant from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (CIHR) for urgent Opioid Crisis Knowledge Synthesis (No. 397977), and a CIHR Foundation grant. Dr. Hohl's salary is supported by the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research through the Health Professional Investigator Award.

Competing interests

None.