INTRODUCTION

Globally, the burden of cardiovascular disease is extremely high, 1 and with the aging of the population, the prevalence is projected to increase substantially in the coming decades.Reference Heidenreich, Trogdon and Khavjou 2 - 4 The diagnosis might be made in the emergency department (ED), where patients often seek care for some of the symptoms of these diseases, such as an abnormally fast heart rate because of atrial fibrillation, an elevated reading on a pharmacy blood pressure machine, or shortness of breath because of heart failure. Depending on illness acuity, these patients may be discharged to their home once an emergency is ruled out.

Most emergency physicians advise such patients to seek follow-up care with their primary care provider (PCP) within a week.Reference Cho, Austin and Atzema 5 Because of a lack of evidence to support a specific follow-up period, guidelines for atrial fibrillation, hypertension, and heart failure vary in their recommendations, but all strongly recommend follow-up care.Reference Stiell and Macle 6 , Reference Wolf, Lo, Shih, Smith and Fesmire 7 In addition to diagnostic testing and counselling on their diagnosis and prognosis, evidence-based medications are often required: for hypertension, this means antihypertensive medicationReference Daskalopoulou, Rabi and Zarnke 8 , Reference James, Oparil and Carter 9 ; for atrial fibrillation, an anticoagulant to prevent strokes and potentially a rate-control agentReference Camm, Kirchhof and Lip 10 - Reference Verma, Cairns and Mitchell 12 ; and for heart failure, several classes of evidence-based medications.Reference McKelvie, Moe and Ezekowitz 13 , Reference Yancy, Jessup and Bozkurt 14 Even if a medication is initiated in the ED, it is the follow-up visit with the PCP that will ensure that the dosage is appropriate and effective in the long-term. 15

At the turn of this century, primary care underwent substantial reform in Ontario, the most populous province in Canada. Several primary care models were introduced into a landscape of almost entirely simple fee-for-service remuneration.Reference Glazier, Zagorski and Rayner 16 These included two mostly capitation-based reimbursement models (“Family Health Network” or “Organization,” the latter offering a slightly larger basket of services to patients than the former) and two enhanced fee-for-service models (“Family Health Group” if three or more physicians or “Comprehensive Care Model” if fewer physicians). All models require the physicians to enrol patients formally (i.e., patient rostering 17 ) and to offer after-hours care (Box 1). The “Family Health Team” was also introduced, but it is not a reimbursement model: it is meant to facilitate the development of a patient-centred medical home, with funding for an interdisciplinary team, an executive director, and electronic medical records. It is only available to physicians in capitation-based reimbursement models.

The new primary care models were introduced to improve access to care and reduce ED utilization, among other reasons, but relatively few studies have rigorously evaluated outcomes such as access to care for specific patient groups.Reference Glazier, Klein-Geltink, Kopp and Sibley 18 - Reference Kiran, Kopp, Moineddin and Glazier 20 In this study, we examined the frequency of follow-up care after an ED visit for a new diagnosis of atrial fibrillation, heart failure, or hypertension and whether such follow-up was associated with the patient, emergency physician, and family physician, and the health care system characteristics, including the family physician’s remuneration method. We hypothesized that the remuneration method would have the strongest association with obtaining follow-up care.

METHODS

Study design

This retrospective cohort study using administrative health datasets was approved by the Research Ethics Board of Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre.

Data sources

Ontario has an ethnically diverse population of 13 million. Eligible patients were identified from the Canadian Institute of Health Information’s (CIHI) National Ambulatory Care Reporting System (NACRS), a dataset that contains abstracted data on all ED visits in Ontario (hospital reporting has been mandatory in Ontario since 2002). 21 NACRS abstractors work at each hospital; they receive standardized CIHI training on how to abstract ED charts. The NACRS dataset holds over 300 data points (some mandatory, some optional); diagnoses are listed using the International Classification of Diseases, Version 10 (ICD 10) codes. Submitted data are reviewed by CIHI (>750 automatic checks), and errors, missing data, or both are identified and returned to the submitting hospital as necessary for resubmission; therefore, missing data for mandatory variables in the NACRS are very low. We have validated the ICD 10 code for atrial fibrillation (I480) in NACRS using ED charts from nine teaching, community, and small hospitals in Ontario (positive predictive value [PPV] 93.0%, 95% confidence interval [CI] 91.6-94.2),Reference Atzema, Austin and Miller 22 as well as codes for hypertension (I10-13) using five teaching and community sites (PPV 95.7%, 95% CI 94.6-96.7).Reference Masood, Austin and Atzema 23

Patients were linked to other administrative health datasets held at the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences using unique, encoded identifiers. These datasets included CIHI’s Discharge Abstract Database (contains all hospitalizations in Ontario, including comorbidities and up to 25 hospital diagnoses); the Registered Persons Database, which contains accurate mortality data (including out of hospital deaths)Reference Iron, Zagorski, Sykora and Manuel 24 ; and the Ontario Health Insurance Plan (contains all physician billings for visits and procedures for medically necessary care in any setting, including home visits and long-term care institutions). Physician specialties were determined from the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences Physician Database, which is derived from information in the Ontario Health Insurance Plan’s Corporate Provider Database, the Ontario Physician Human Resource Data Centre database, 25 and the Ontario Health Insurance Plan. Ontario provides universal healthcare coverage for its residents; therefore, the databases contain the large majority of health care visits in the province.

In Ontario, primary care is mostly provided by family physicians, whom patients can choose without restriction (although some do not take new patients because of a full roster). To access specialist care (such as an internist or cardiologist), the patient must first obtain a referral from another physician. The patient’s family physician was determined using the Client Agency Program Enrolment tables, and that physician’s primary care remuneration model type was determined from the Corporate Provider Database (each physician can belong to only one type). If a patient was not enrolled with a family physician during the year of the ED visit (<10% of patients in Ontario), we employed a virtual rostering method to assign the patient to a family physician; the patient was assigned to the family physician with whom they had the majority of their primary care services in the two years prior to the emergency visit. If a patient was not enrolled with a family physician or could not be assigned using virtual rostering (i.e., no primary care visits in the prior two years), the patient was considered to have no family physician. As a sensitivity analysis, we also examined the results if all patients were simply assigned using the virtual rostering method, an approach that tends to assign healthy patients to the “no family physician” group because they have not seen a family physician in several years, when in fact, they may have a family physician.

Study population

We included patients aged 18-105 who were seen in an Ontario ED between April 1, 2007, and March 31, 2014, for whom the first-listed diagnosis was one of three ambulatory-sensitive cardiovascular conditions: atrial fibrillation (ICD-10 code I480), hypertension (I10-I13), and heart failure (I50). Subjects had to have a valid Ontario Health Card number to be included, and repeat visits by the same patient during the study period were excluded. We also excluded patients who received a low ED acuity triage score (four or five out of five),Reference Beveridge, Clarke and Janes 26 those who died in the ED, and those who were admitted to the hospital (as we were assessing follow-up care after an ED visit, not following an in-hospital stay). We excluded specialty EDs (i.e., solely pediatric, mental health, or cancer) and those that were not open 24 hours a day. To create an incident cohort, among patients with an ED diagnosis for each disease, we excluded those with a history of that disease defined as an ED visit, hospitalization, or outpatient visit for that disease in the five years prior to the index date (e.g., for patients with an ED visit for heart failure, we excluded those with any such visit/hospitalization for heart failure, while a prior visit for atrial fibrillation would not remove them from the heart failure cohort).

We divided the patients into income categories based on the median household income of their neighbourhood, using Statistics Canada Census data; postal codes were used to form quintiles based on average income in the dissemination area. Rural residence was defined using the Statistics Canada definition of fewer than 10,000 residents. If available, patient comorbidities were determined using validated algorithmsReference Gershon, Wang and Guan 27 - Reference Tu, Campbell, Chen, Cauch-Dudek and McAlister 31 or using either one hospitalization code or two outpatient visits with that comorbidity in the five years prior to the index visit (similar to many of the validated algorithms).

Outcome measures

The primary outcome measure was receipt of outpatient follow-up care with a family physician, an internist, or a cardiologist within seven days of discharge. Seven days was selected based on emergency physician requests for post-ED follow-up care and cardiovascular disease recommendations.Reference Cho, Austin and Atzema 5 , Reference Hernandez, Greiner and Fonarow 32 The secondary outcome measure was receipt of outpatient follow-up care within 30 days.

Data analysis

We used descriptive statistics to report the percentage of patients who obtained 7-day and 30-day follow-up care. Next, we regressed the cause-specific hazard of receiving follow-up care on patient-, provider-, and systems-level characteristics using a cause-specific hazard model that accounted for the competing risks of death or hospitalization. Subjects were censored after 7 days if they were event-free (had not yet received follow-up care, died, or been hospitalized). The cause-specific hazard model formally accounts for these competing risks and does not assume that competing events are independent of the event of interest. To assess the association of specific family physician characteristics with the cause-specific hazard of receiving follow-up care, we also created a model excluding patients who did not have a family physician (as inclusion of these patients would result in family physician characteristics that appear to be “missing” for those patients, when in fact, there was no such physician). The process was repeated for patients who obtained follow-up care for 30 days, instead of 7 days (or for corresponding competing risks). To account for clustering of patients within EDs, we employed robust sandwich-type variance estimates. For ED visits that could not be linked to an emergency physician billing code (academic EDs used shadow-billing prior to 2007, and uptake was gradual thereafter because of reduced billing rates at those sites), emergency physician characteristics were imputed using multiple imputation (8.7%).

As a sensitivity analysis, we examined the results of the seven-day model if patients were assigned to family physicians solely based on the virtual rostering method. All analyses were performed using SAS software (Version 9.3, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

There were 41,485 eligible visits to 157 EDs in Ontario (Table 1). The median patient age was 64.0 years; 49.9% of the visits were made by females; and 92.6% of the patients had a family doctor. Just under one-half (47.0%; 95% CI 46.5-47.5) had obtained care with a family physician, a cardiologist, or an internist within a week of discharge, with 78.7% (95% CI 78.3-79.1) obtaining care within 30 days. The majority of the follow-up care was provided by the family physician (Table 2). There were 141 (0.3%) deaths within 7 days of discharge and 490 (1.2%) deaths within 30 days; 1,694 (4.1%) patients were admitted to the hospital (for any reason) within 7 days, and 3,509 (8.9%) patients were admitted within 30 days.

Table 1 Baseline characteristics of 41,485 patients discharged from the ED with a new diagnosis of hypertension, atrial fibrillation, or heart failure

ADG=Adjusted Diagnosis Group 56 ; CCM=Comprehensive Care Model; CI=confidence interval; ED =Emergency Department; EM=emergency medicine; FFS=fee-for-service; FHG=Family Health Group; FHN=Family Health Network; FHO=Family Health Organization; FHT=Family Health Team; Family med=family medicine; LTC=long-term care.

Table 2 Follow-up care among 41,485 patients discharged from the ED with a new diagnosis of a cardiovascular disease

* N/A=not applicable (if death occurred by day 7, then no additional follow-up visits could occur between days 8 and 30)

† Cannot be reported because of small cell sizes (≤5), in agreement with Canadian Institute for Health Information

Box 1 Description of primary care model types in OntarioReference Glazier, Klein-Geltink, Kopp and Sibley 18

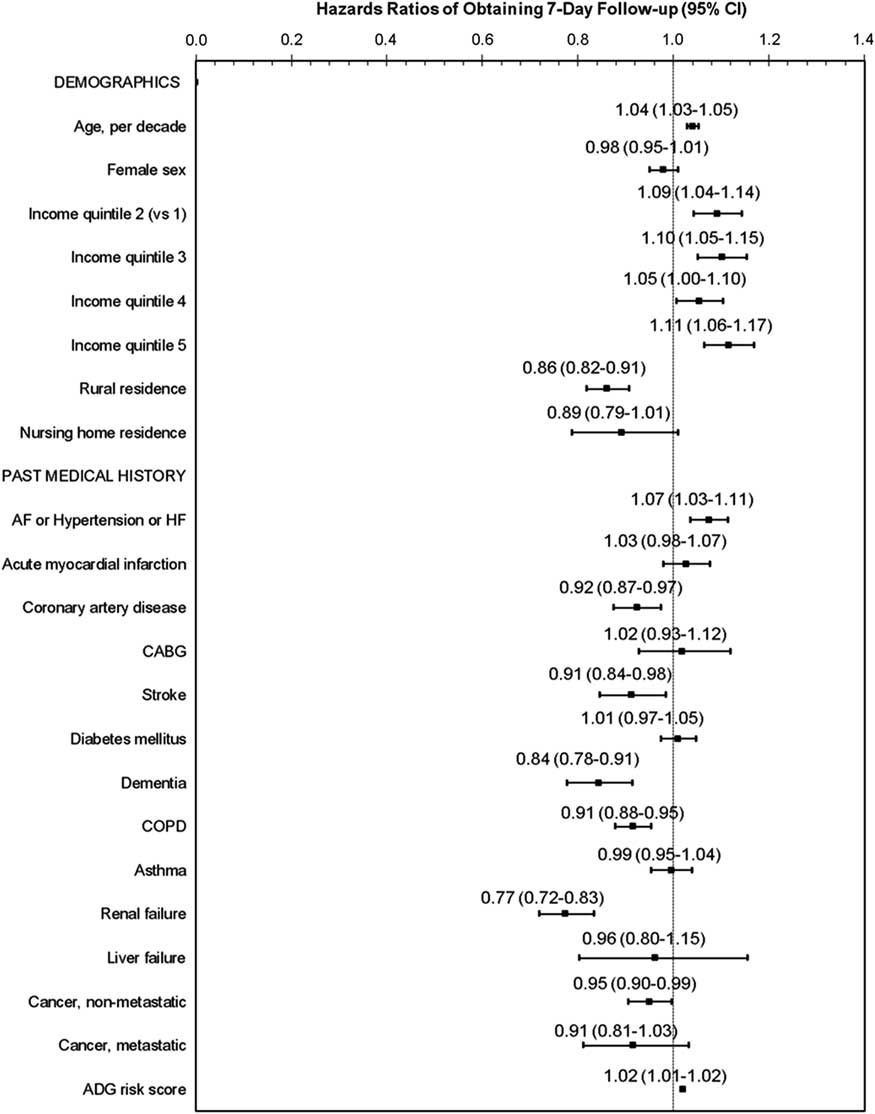

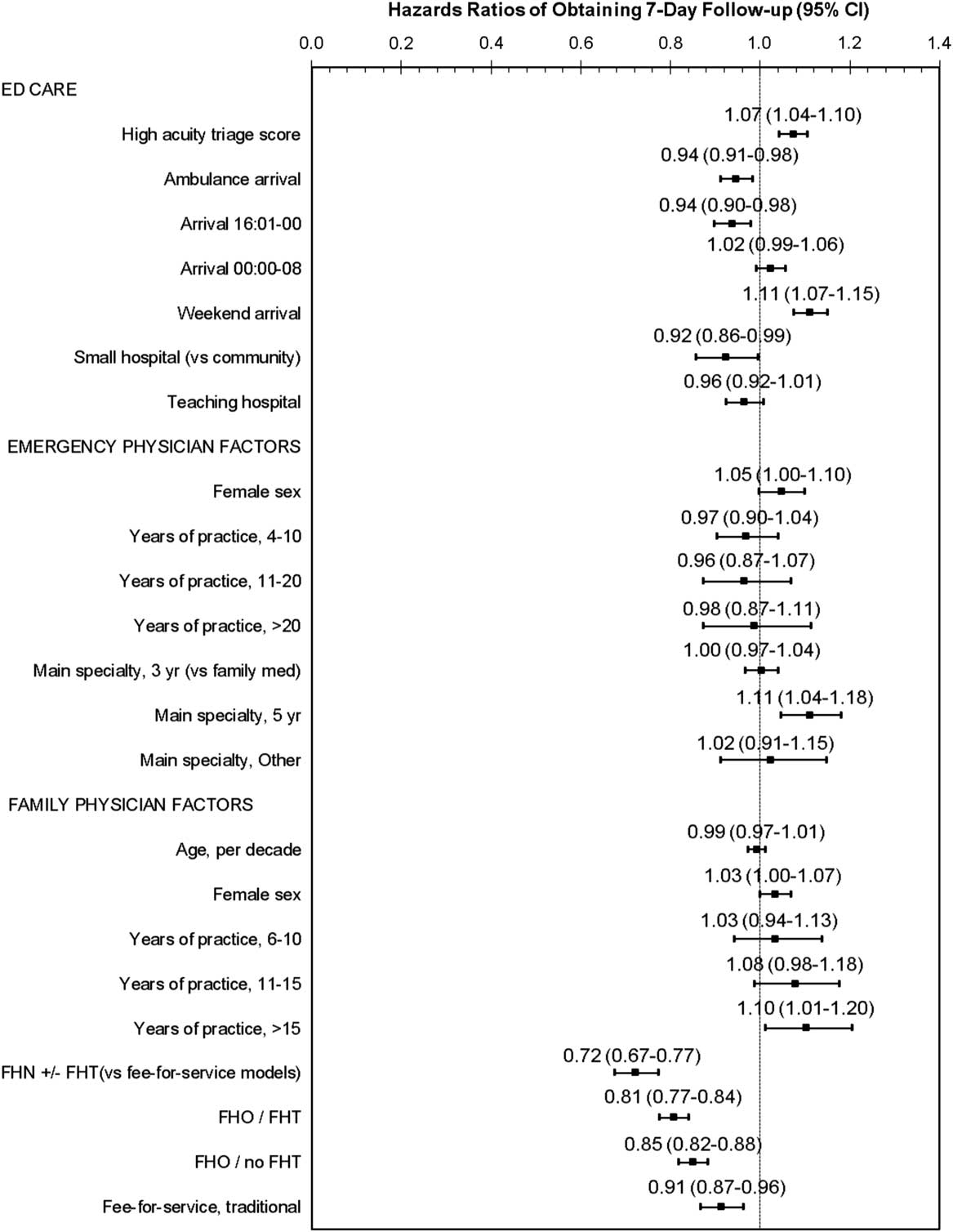

In the seven-day follow-up care model, the lack of a family physician had the strongest association with obtaining follow-up care, with an adjusted hazard ratio (HR) of 0.58 (95% CI 0.54-0.63). In the model that was limited to patients who had a family physician (shown in Figure 1), patients with a history of renal failure, dementia, stroke, coronary artery disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and cancer had a lower association with obtaining follow-up care within a week, as did patients with a rural residence and low socioeconomic status. Older age, higher income status, and a history of one of the ambulatory-sensitive cardiovascular conditions were associated with improved frequency of follow-up care.

Figure 1 Patient factors: Adjusted hazard of obtaining follow-up care by a family physician, cardiologist, or internist, within 7 days of emergency department discharge, among patients who had a family physician ADG=Adjusted Diagnostic Group 56 ; AF=atrial fibrillation; CABG=coronary artery bypass graft; CI=confidence interval; COPD=chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; HF=heart failure.

The only emergency physician characteristic that was independently associated with follow-up care was emergency physician specialty: patients who saw emergency physicians with five years of specialty training in emergency medicine were 11% more likely to obtain seven-day follow-up care than those who were seen by a physician with family medicine training (Figure 2). Among family physician characteristics, the only significant characteristic was more years in practice (>15 years), with a 10% higher adjusted association with obtaining follow-up care, as compared with those whose family physician had been in practice for five years or less.

Figure 2 Physician and visit factors: Adjusted hazard of obtaining follow-up care by a family physician, cardiologist, or internist, within 7 days of emergency department discharge, among patients who had a family physician CCM=Comprehensive Care Model; CI=confidence interval; FHG=Family Health Group; FFS=fee-for-service; FHO=Family Health Organization; FHN=Family Health Network; FHT=family health team.

Significant systems factors included the remuneration method (Figure 2); patients whose family physician was remunerated primarily through a capitation model had a 15%-28% lower hazard of obtaining follow-up care within a week, as compared with those whose family physician was remunerated through enhanced fee-for-service models. Patients whose family physicians were remunerated through simple fee-for-service had a 9% lower risk of obtaining seven-day care than those whose physicians had enhanced fee-for-service models. Patients seen at small hospitals had a slightly (8%) lower hazard of receiving seven-day follow-up care, as compared with community hospitals.

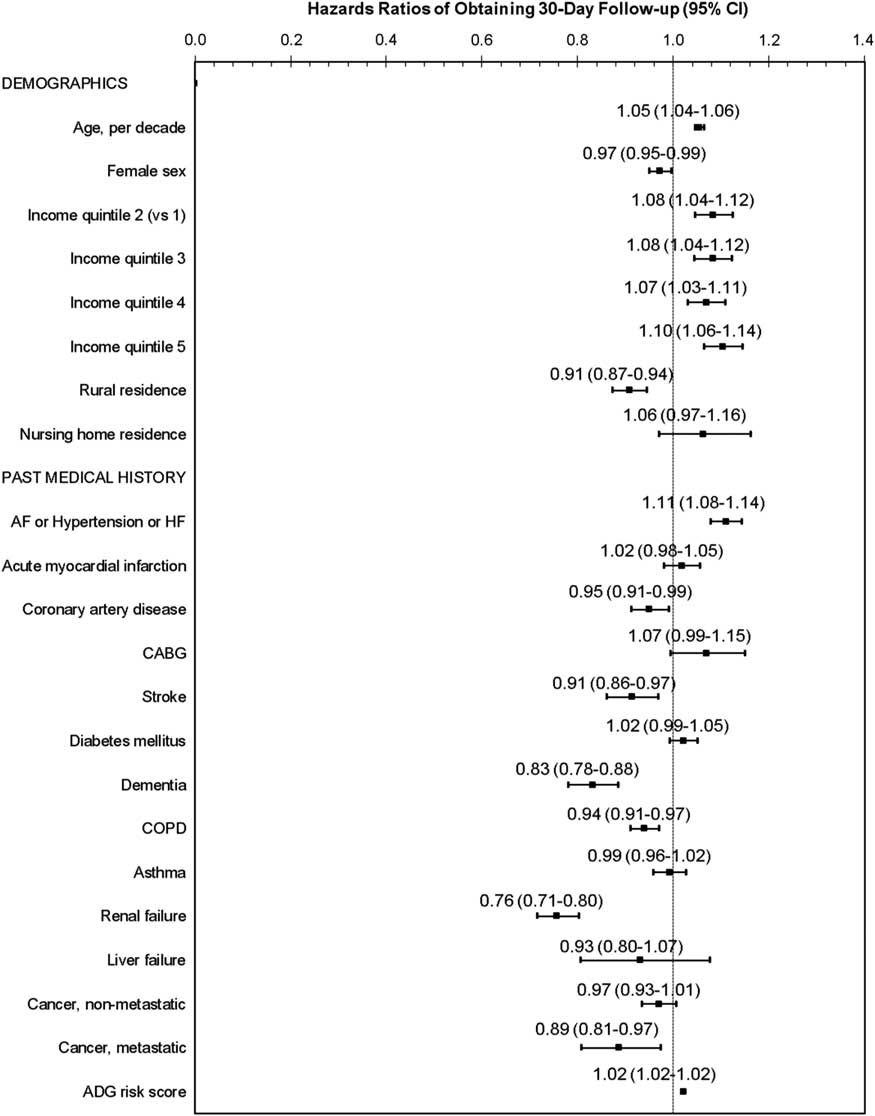

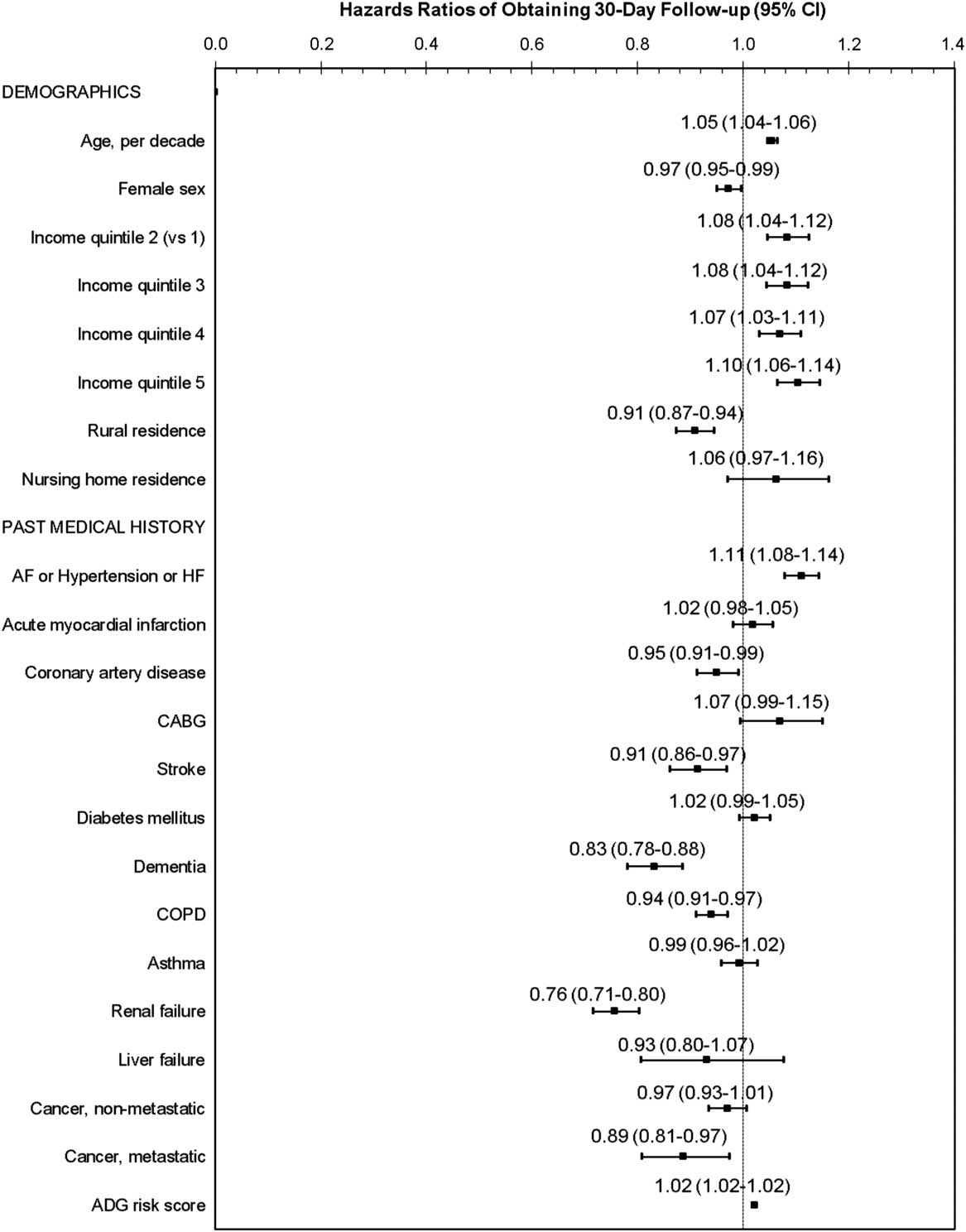

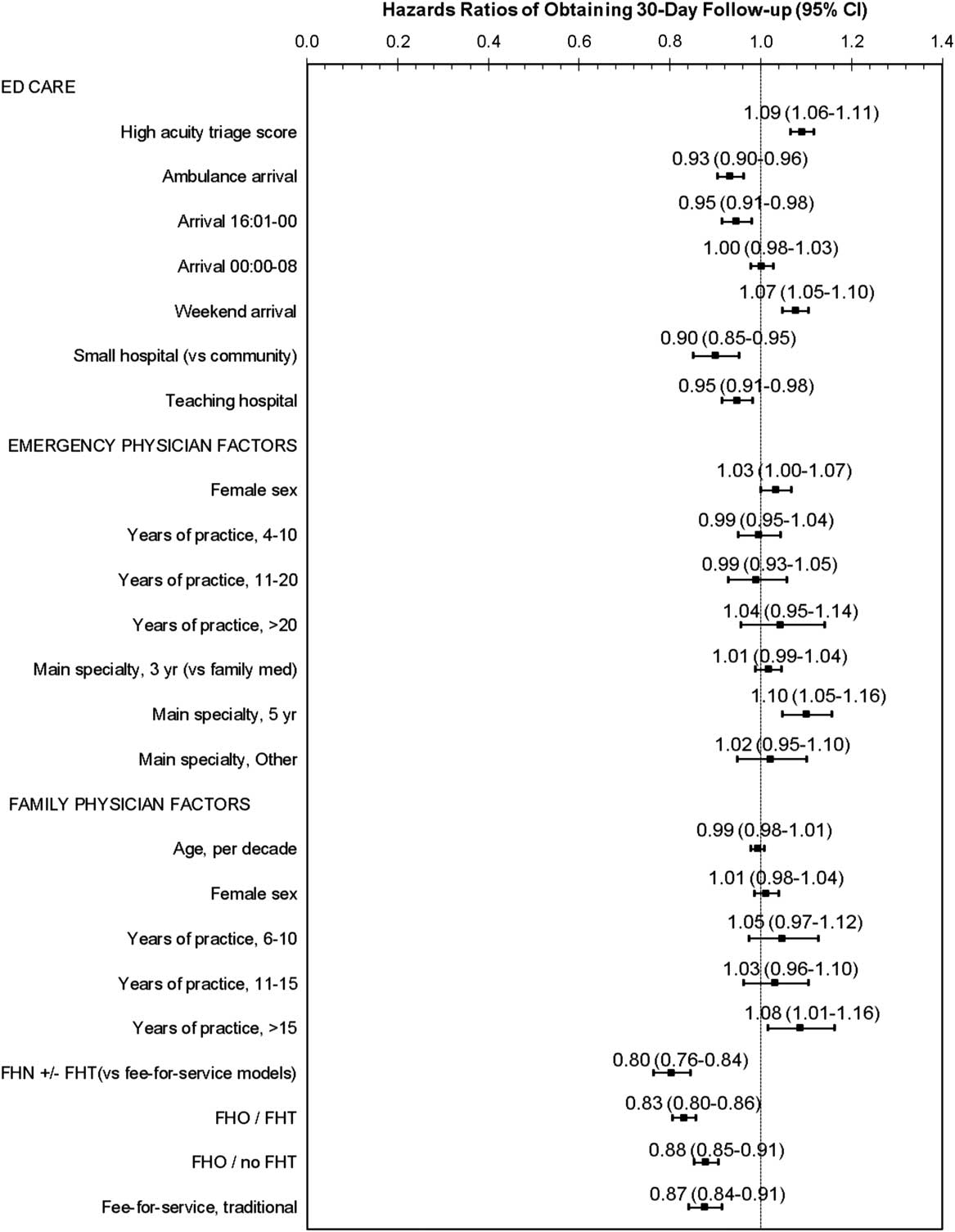

The findings were similar for the 30-day models (Figures 3 and 4). The factor with the strongest association with follow-up care was again a lack of a family physician (HR 0.61, 95% CI 0.58-0.65). In the patient-level variables, obtaining 30-day follow-up care was significantly lower for patients with metastatic cancer, in addition to the same patient-level variables that were associated with seven-day follow-up care. Primary care model type remained associated with 30-day follow-up care, but the hazards were slightly attenuated, with a 12% to 20% lower risk of obtaining follow-up care, as compared with patients who had a family physician remunerated through an enhanced fee-for-service model. In the sensitivity analysis in which patients were assigned to a family physician using solely virtual rostering, the results were similar.

Figure 3 Patient factors: Adjusted hazard of obtaining follow-up care by a family physician, cardiologist, or internist, within 30 days of emergency department discharge, among patients who had a family physician ADG=Adjusted Diagnostic Group 56 ; AF=atrial fibrillation; CABG=coronary artery bypass graft; CI=confidence interval; COPD=chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; HF=heart failure.

Figure 4 Physician and visit factors: Adjusted hazard of obtaining follow-up care by a family physician, cardiologist, or internist, within 30 days of emergency department discharge, among patients who had a family physician CCM=Comprehensive Care Model; CI=confidence interval; FHG=Family Health Group; FFS=fee-for-service; FHO=Family Health Organization; FHN=Family Health Network; FHT=family health team.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we found that less than one-half of patients who were newly diagnosed with a chronic cardiovascular disease were seen within a week of being discharged from an ED in the province of Ontario. A month later, 21% of these patients still had not seen an appropriate physician to either initiate or continue/modify disease management. This is important because a previous study found that a lack of follow-up care was associated with higher mortality at 90 days for ED patients discharged with atrial fibrillation,Reference Atzema, Austin, Chong and Dorian 33 and another demonstrated higher mortality for patients with heart failure who were not seen within 30 days.Reference Lee, Stukel and Austin 34 In a randomized controlled trial of outpatients who had extremely high blood pressure (e.g., diastolic 115-130 mm Hg) without any signs of accelerated hypertension, subjects who did not receive antihypertensive therapy had a higher frequency of death and hospitalization for hypertensive complications, as compared with treated subjects.Reference Freis, Arias and Armstrong 35 Atrial fibrillation is associated with worse quality of life following ED discharge,Reference Ballard, Reed and Singh 36 and lack of follow-up care decreases the opportunity to manage symptoms; in turn, this may result in more return visits to the ED.Reference Ivers and Dorian 37 Indeed, we have previously found that follow-up care with a cardiologist was associated with fewer return ED visits for atrial fibrillation within 14 days of ED discharge.Reference Atzema, Dorian, Ivers, Chong and Austin 38 Lastly, for patients who are not given a prescription in the ED, the wait until further evaluation and initiation of medication might decrease the sense of urgency for the patient to take chronic medications (particularly if no adverse outcome occurs during that time period, such as a stroke for patients with atrial fibrillation), potentially resulting in decreased long-term medication adherence.Reference Atzema, Austin, Chong, Dorian and Jackevicius 39 Therefore, patients discharged from an ED with a new cardiovascular disease constitute a preselected group who need to be prioritized for an early follow-up assessment that only one-half are receiving.

While our results suggest that both patient- and systems-level factors are at play, the most influential factor in our study was having a family physician. This is an intuitive finding, which has been demonstrated in other patient groups who were discharged from an ED,Reference Dinh, Chu and Zhang 40 , Reference Qureshi, Asha, Zahra and Howell 41 and lends face validity to our study findings. With the establishment of the Affordable Care Act in the United States, many more Americans now have access to health insurance,Reference Blumenthal, Abrams and Nuzum 42 and with it, a PCP, suggesting that ED follow-up care is likely to improve in that country if the legislation remains in place.

Similar to previous work, a rural address and lower socioeconomic status were associated with less follow-up careReference Withy and Davis 43 , Reference Weissman, Stern, Fielding and Epstein 44 ; this is despite universal health care that is provided in Ontario. Other studies have also demonstrated the inability of universal health care to negate the impact of socioeconomic status on health,Reference Fein 45 , Reference Olah, Gaisano and Hwang 46 although others have shown that insurance is an important predictor of obtaining follow-up care after an ED visit.Reference Qureshi, Asha, Zahra and Howell 41 , Reference Milano, Carden and Jackman 47 , Reference Mouton, Beaudouin, Troutman and Johnson 48 Therefore, it appears that insurance is a necessary but not a sufficient criterion for obtaining timely ED follow-up care.

After having a PCP, the next most important factors were not related to patients themselves but to the remuneration model of their PCP. Patients with physicians who were remunerated through enhanced fee-for-service models were substantially more likely to be seen within both a week and a month of discharge with a new diagnosis of heart failure, atrial fibrillation, or hypertension, as compared with those with a physician who was remunerated through primarily capitation-based models. Another study demonstrated that patients who were enrolled with a physician who was remunerated through primarily capitation-based models had less after-hours care and higher ED visit rates compared with those seen in primarily fee-for-service models,Reference Glazier, Klein-Geltink, Kopp and Sibley 18 which might partly explain the lower access to timely follow-up care. We speculate that the difference in model types could also be because of tighter schedules in primarily capitation-based offices, which is meant to encourage physicians to spend more time with patients. Practices using these models have been shown to have better disease screening than those that use enhanced fee-for-service modelsReference Kiran, Victor, Kopp, Shah and Glazier 19 , Reference Kiran, Kopp, Moineddin and Glazier 20 ; however, our results suggest that this may be at the cost of providing early access to care. The enhanced feefor-service model may also provide a financial incentive to squeeze another patient into an already full schedule.

Patients with PCPs who were remunerated by simple fee-for-service billings were slightly less likely to obtain seven-day follow-up care than those with formal fee-for-service models. The latter finding is likely explained by the improved access to after-hours care that is mandatory in enhanced fee-for-service models. Future studies are needed to assess these factors, as well as the impact of primary care office scheduling practices.Reference Fournier, Heale and Rietze 49

It is concerning that patients with serious comorbidities such as renal failure, dementia, COPD, stroke, cancer, and coronary artery disease were less likely to obtain follow-up care within a week or month of discharge. One might expect that these patients have better linkage within the healthcare system because of their comorbidities and therefore better access to follow-up care. In addition, patients with these comorbidities represent a higher-risk group for poor outcomes and therefore require early follow-up care. We hypothesize that these patients are either less able to pursue follow-up care because of their illness burden (i.e., less access to transportation and too sick to make multiple phone calls to book the appointment),Reference Naderi, Barnett and Hoffman 50 - Reference Smith, Highstein, Jaffe, Fisher and Strunk 52 and/or are desensitized to the risks of a poor outcome, secondary to already living with a serious disease. Alternatively, these patients might prioritize other diseases over their new diagnosis. Two other studies found that patients with comorbidities were more likely to obtain follow-up care, but the results were unadjustedReference McCarthy, Hirshon and Ruggles 53 , Reference Scherer and Lewis 54 and therefore might be confounded by other factors. Future research is needed to determine the specific links between comorbidity burden and lack of follow-up for these higher-risk patients.

LIMITATIONS

The Client Agency Program Enrolment tables are updated annually; however, their size (~13 million Ontarians) leads to some delay in capturing patients who change doctors. We assessed the potential impact by performing a sensitivity analysis that assigned patients to the doctor whom they saw most frequently; our results did not change substantially. Bias is possible because of potential under-billing in capitation-based practices. For example, nurses might provide care in practices that are a part of Family Health Teams; however, as the findings were the same for capitation-based practices that were not part of a Team, this is unlikely to account for the differences observed. Capitated providers have incentives to conduct follow-up through phone or email, which would not result in billing; however, a new diagnosis of a cardiovascular disease should include a physical examination,Reference Daskalopoulou, Rabi and Zarnke 8 , Reference January, Wann and Alpert 11 , Reference McKelvie, Moe and Ezekowitz 13 , Reference Yancy, Jessup and Bozkurt 14 , Reference Chobanian, Bakris and Black 55 which would not be possible with these communication methods.

We included visits to only family physicians, internists, and cardiologists, assuming that during any visits to orthopedic surgeons, sports medicine physicians, etc., following discharge, the cardiovascular disease was not managed by these practitioners. Moreover, even if the patient sees a subspecialist (e.g., a respirologist), the baton of care has not been effectively passed because even if that specialist provides the patient with a prescription renewal (e.g., an anticoagulant for patients newly diagnosed with atrial fibrillation), it is unlikely that they will provide ongoing disease management (e.g., future prescription renewals, scheduling of an echocardiogram, etc.). Therefore, continuity of care has likely not been achieved during subspecialist visits; thus, we did not count such a visit as true follow-up care. However, certain subspecialists might be more likely to assume ongoing cardiovascular disease management (e.g., hypertension by a nephrologist); these visits were rare (<0.5% additional follow-up visits made within 30 days) and therefore are unlikely to alter our results.

CONCLUSIONS

In this population-based study, less than one-half of patients who were discharged from an ED with a new diagnosis of atrial fibrillation, heart failure, or hypertension had follow-up care within a week. Among patient and provider variables, having a PCP had the greatest impact on receipt of follow-up care, and the remuneration model of that physician was the next most important factor. One-week and one-month follow-up care were less likely to occur if the patient’s PCP was remunerated through primarily capitation, as compared with patients whose provider was reimbursed using an enhanced fee-for-service model. In general, patients with serious comorbidities were less likely to obtain timely follow-up care. Systems-wide solutions are needed to target these variables so patients discharged from an ED with a new diagnosis of an ambulatory-sensitive cardiovascular disease transition to ongoing care in a safe and timely way.

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) grant. CLA was supported by a New Investigator Award from the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Ontario, DSL was supported by a mid-career investigator award from the Heart and Stroke Foundation and is the Ted Rogers Chair in Heart Function Outcomes, NMI was supported by a New Investigator Award from CIHR, MJS was supported by Applied Chair in Health Services and Policy Research from CIHR, and PCA was supported by a Career Investigator Award from the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Ontario.

Competing interests: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The University of Toronto was not involved in the design or conduct of the study; data management or analysis; or manuscript preparation, review, or authorization for submission. Parts of this material are based on data and information compiled and provided by CIHI. However, the analyses, conclusions, opinions, and statements expressed herein are those of the author and not necessarily those of CIHI. This study was supported by the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES), which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC). The opinions, results, and conclusions reported in this paper are those of the authors and are independent of the funding sources. No endorsement by ICES or the Ontario MOHLTC is intended or should be inferred.