1. Introduction

This article provides the first detailed linguistic description of motion verbs in the Kainaa dialect of Blackfoot, a Plains Algonquian language spoken in Southern Alberta and North-western Montana.Footnote 1 The particular focus of this article is twofold. One is to describe how an inherent endpoint of a motion event can be expressed in Blackfoot; this endpoint will be shown to be associated with the presence of a certain type of an external argument, that is, a sentient DP that is an agent. The other is to provide a formal analysis of the association between a sentient external argument and an inherent endpoint of the motion verbs.

Lexical aspect (henceforth, aspect) refers to the internal temporal properties of the event described, where the properties of an event are determined not by a verb alone, but by the verb and its internal argument, that is, a VP (Verkuyl Reference Verkuyl1972, Dowty Reference Dowty1979, van Voorst Reference van Voorst1988, Tenny Reference Tenny1994). An event can be minimally described in terms of whether or not it has a distinct or inherent endpoint. Following Tenny (Reference Tenny1994), I refer to this property of an event as delimitedness.Footnote 2 For instance, a goal PP of a motion event can indicate that an event is delimited (Dowty Reference Dowty1979, Jackendoff Reference Jackendoff1990, Pustejovsky Reference Pustejovsky1991, Smith Reference Smith1991, Tenny Reference Tenny1994, Borer Reference Borer2005, Ramchand Reference Ramchand2007, MacDonald Reference MacDonald2008a, Travis Reference Travis2010 among many others). Consider the English examples in (1). The sentence in (1a) expresses an event of ‘the ball rolling’. The event in (1a) is considered to be non-delimited without an endpoint; it is not specified when the event of rolling finished, that is, was completed. However, the event can become delimited by the addition of a goal PP such as ‘into the river’ as shown in (1b): the event of the ball rolling was completed by the time the ball reached the river. Although the details differ, this type of a goal PP that marks an endpoint has been proposed to be VP-internal (e.g., Borer Reference Borer2005, Ramchand Reference Ramchand2007, MacDonald Reference MacDonald2008a, Tungseth Reference Tungseth2008, Travis, Reference Travis2010). Following these previous studies, I assume that a goal PP that marks an endpoint belongs to a VP-internal position.

(1)

a. The ball rolled.

b. The ball rolled into the river.

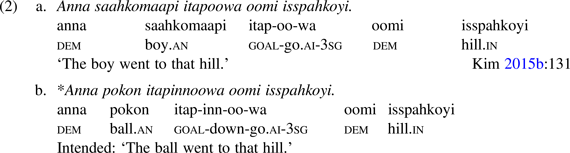

The data in (1) shows that an internal argument such as a goal PP (1b) alone can be associated with event delimitedness of the VP. However, as will be shown in this article, an internal-goal PP in Blackfoot cannot appear without a certain type of a subject, namely a sentient DP, and it is further shown that the sentient subject in question has to be an agent (not a theme). Sentience refers to real-world or semantic animacy, or the ability to sense or perceive (Speas and Tenny 2003). To illustrate, some of the core data of Blackfoot are provided in (2) (see section 4 for details, and Table 3 for a summary).Footnote 3, Footnote 4 The goal PP ‘to that hill’ is allowed with the sentient subject anna ssahkomaapi ‘the boy’ as shown in (2a), but it cannot appear when the subject is non-sentient anna pokon ‘the ball’ as the ungrammaticality of the sentence in (2b) suggests. This article demonstrates that a sentient subject such as ‘the boy’ in (2a) has to be an agent to delimit the event by allowing a goal PP.

Building on this type of data, I propose that in Blackfoot, event delimitedness is associated with a sentient external argument. I further propose that such a sentient external argument is an event initiator (initiator, henceforth), and as such it has a determining role in the delimitedness of VP, as in Ritter and Rosen (Reference Ritter, Rosen, Tenny and Pustejovsky2000). Under the proposed account, aspect in Blackfoot is initiation-oriented with a language-specific requirement that an initiator be sentient. The association between a sentient subject and event delimitedness in Blackfoot is not exactly the same as in English, where an event can be delimited by adding a direct object (e.g., ‘John painted’ vs. ‘John painted a portrait’). As will be shown in section 4 (also, see section 2), event delimitedness in Blackfoot can be understood as being less direct than in English, as pointed out by an anonymous reviewer: the delimitedness interpretation of the VP indicated by a goal PP is visible only when a particular type of a subject, a sentient agent, is present.Footnote 5

My proposal that Blackfoot aspect is sentient initiator-oriented constitutes strong empirical support for the prevailing view in which grammar of Blackfoot is sentience-dominant (e.g., Frantz Reference Frantz2009, Johansson Reference Johansson2009, Meadows Reference Meadows2010, Ritter and Rosen Reference Ritter, Rosen, Rappaport-Hovav, Doron and Sichel2010, Bliss Reference Bliss2013, Kim Reference Kim2014b, Ritter Reference Ritter2015, Wiltschko and Ritter Reference Wiltschko and Ritter2015). Regarding the theoretical perspective, a major contribution of the current study is to detail how an external argument is associated with the delimitedness of VP, a property which has previously been viewed as linked with the internal argument only (Tenny Reference Tenny1987; MacDonald Reference MacDonald2008a, Reference MacDonaldb).

This article is structured as follows. Section 2 discusses the proposal of Ritter and Rosen (Reference Ritter, Rosen, Tenny and Pustejovsky2000), who argue that in some languages an event can be delimited only in the presence of an event initiator. This section thus provides an important foundation for the central claim of this article that aspect in Blackfoot is event-initiator oriented. Section 3 provides background on Blackfoot. Section 4 proposes a formal analysis that captures the sentient initiator-oriented event structure of motion verbs in Blackfoot. Section 5 concludes the article.

2. Initiation and delimitedness in event structure

One dominant view of event structure is that events are represented in functional projections (FPs) and that event descriptions are compositionally determined by certain eventive contents or features of these FPs (e.g., Borer Reference Borer, Benedicto and Runner1994, Reference Borer2005; Ritter and Rosen Reference Ritter, Rosen, Tenny and Pustejovsky2000; van Hout Reference van Hout, Alexiadou and Everaert2004; Thompson Reference Thompson2006; Ramchand Reference Ramchand2007; MacDonald Reference MacDonald2008a, Reference MacDonaldb; Travis Reference Travis2010). In particular, the relevant features of these FPs are identified by certain arguments when those arguments occupy the specifier of the FPs. Although the particular event features in question differ across studies, two event features appear to be generally recognized in the studies of event structure: initiation and delimitation. The initiation point is identified with an argument that launches or initiates the event, while the delimitation point is identified with an argument that terminates or completes the event.

To illustrate, consider the schematic event structure in (3) adopted from Ritter and Rosen (Reference Ritter, Rosen, Tenny and Pustejovsky2000). Note that the structure in (3) is a simplified schematic without bar levels. For reasons of space, structures discussed in this article are illustrated this way. In (3), the head of FPinit has the feature [initiation], and appears above an external argument introducing a head such as v. The head of FPdelim has feature [delimited(ness)] and appears between v and VP.

An initiating event can be identified by an argument that is capable of launching or initiating the event, the initiator. For example, an argument such as an agent (DPag) in the specifier of vP receives an event role of initiator by occupying the specifier of FPinit; for example, by raising to the specifier of FPinit. A delimited event can be identified by a certain type of an internal argument (e.g., a goal PP or a quantized object) that occupies the specifier of FPdelim; for example, a goal PP in VP raises into the specifier of FPdelim.

An event initiator is responsible for launching or initiating the event, but it is compatible with a range of thematic roles that conform to this property of initiator: a (volitional) agent, cause, or instrument. The range of thematic roles that an initiator may have is not the same across languages; for example, in some languages, but not in others, a cause or an instrument is allowed as an event initiator. Note that there is no assumption in either this article or in Ritter and Rosen (Reference Ritter, Rosen, Tenny and Pustejovsky2000) that an initiator or an agent has to be sentient. In Ritter and Rosen (Reference Ritter, Rosen, Tenny and Pustejovsky2000), not all initiators are agents and an initiator need not be sentient; for example, an instrument can act in this role. Languages differ as to which thematic roles can be an initiator and as to whether sentience is required or not. In section 4, I show that Blackfoot is a language that requires the agent to be an initiator. Moreover, sentience is shown to be a language-specific property of initiators.

Under the event structure discussed above, it has been proposed that languages can vary as to whether initiation, or delimitedness, is the more active (Ritter and Rosen Reference Ritter, Rosen, Tenny and Pustejovsky2000): I (initiation) languages vs. D (delimitation) languages. Under this view of variation, languages can have only one functional head specified for the relevant feature, either [initiation] on Finit or [delimited] on Fdelim. In a D-language such as English, the feature [delimited] is specified on Fdelim, but the feature [initiation] on Finit is not. Thus, a delimited event in a D-language is available without an initiator as long as an internal argument that satisfies the feature [delimited] on Fdelim exists. For example, the goal PP ‘into the river’ in (1) delimits the event, even though the subject ‘the ball’ is not an initiator.

In an I-language, on the other hand, Ritter and Rosen (Reference Ritter, Rosen, Tenny and Pustejovsky2000) proposed that FPdelim lacks an inherent [delimited] feature, and thus, Fdelim alone cannot indicate that an event is delimited. Instead, an event can be delimited only if an initiator licensed by the feature [initiation] on Finit is present (though note that it is not the case that the presence of an initiator always induces a delimited event).Footnote 6 Thus, in an I-language, it is predicted that the presence of a delimiting phrase such as a goal PP is not sufficient to delimit an event; an initiator has to be present. I will show that this prediction is borne out by the data from Blackfoot. According to Ritter and Rosen (Reference Ritter, Rosen, Tenny and Pustejovsky2000), in an I-language where agency is a factor for an initiator, only an agent (DPag) can raise to the specifier of FPinit to obtain an event role of initiator. A non-agentive DP cannot raise to the specifier of FPinit and thus cannot be an initiator; a non-initiator remains below in vP.

I argue that Blackfoot is an I-language, since aspect, in Blackfoot, is initiator-oriented; that is, the feature [initiation] is active, but not the feature [delimited]. Thus, the delimitedness interpretation of a goal PP of a motion event in the language can be visible only when a sentient initiator is present (see (2a) vs. (2b)). Just as only certain kinds of internal arguments delimit events in D-languages (e.g., goal PPs in English), only certain types of external arguments initiate events in I-languages. Specifically for Blackfoot, event initiators must be sentient and have an agent role.

I would now like to briefly discuss proposals that distinguish between the external argument introducing heads Voice and v, (Alexiadou et al. Reference Alexiadou, Anagnostopoulou and Schäfer2015, Tollan and Oxford Reference Tollan, Oxford, Bennett, Hracs and Storoshenko2018). The core proposal of these studies is that an agent appears in a structurally higher position than a causer or a doer does. Specifically, an agent appears in the specifier of VoiceP, and a causer or a doer appears in the specifier of vP. Regarding an event initiator in an I-language, which allows only an agent argument to be an initiator, these proposals predict that an agent introduced by VoiceP can be an event initiator, but that a non-agent introduced by vP cannot. Interestingly, Tollan and Oxford (Reference Tollan, Oxford, Bennett, Hracs and Storoshenko2018) proposed that the distinction between Voice and v is supported by data from Plains Cree and Oji-Cree, two Algonquian languages. As Blackfoot is also part of this family, it is reasonable to think that it may also have a similar distinction between Voice and v. If so, event initiators in Blackfoot originate from agents in the specifier of VoiceP, but those in the specifier of vP cannot be event initiators. I agree that the distinction between an agent and a non-agent occurs in Algonquian languages; this distinction is visible in Blackfoot, as suggested by the data shown here, but at this stage it is unclear whether the heads Voice and v are the relevant heads for agent and non-agents in Blackfoot in the same way as proposed in Tollan and Oxford (Reference Tollan, Oxford, Bennett, Hracs and Storoshenko2018). This is because the core evidence for the distinction between Voice and v in Algonquian provided in Tollan and Oxford (Reference Tollan, Oxford, Bennett, Hracs and Storoshenko2018) does not fit with the Blackfoot data discussed in this article (see footnote 7 in the next section). Thus, I leave this issue for further research.

3. Background on Blackfoot

This section discusses some properties of Blackfoot grammar that will provide a basis for the understanding of the discussion in the rest of the article. The focus is on animacy and verb classification.

Blackfoot grammar distinguishes two types of animacy (e.g., Bliss Reference Bliss and Christoph Wolfart2007; Frantz Reference Frantz2009; Ritter and Rosen Reference Ritter, Rosen, Rappaport-Hovav, Doron and Sichel2010; Wiltschko and Ritter Reference Wiltschko and Ritter2015; Kim Reference Kim2014b, Reference Kim, Macaulay and Noodin2018), namely grammatical animacy and semantic animacy. Grammatical animacy determines noun class and is morphologically reflected on agreement, for example, on a verb (see the discussion on verb classification below). Nouns are categorized into two grammatical classes: animate and inanimate. Nouns in the grammatically inanimate class are ontologically inanimate objects or things. Nouns in the grammatically animate class may be humans or animals such as saahkomaapi ‘boy’, but may also be certain inanimate things. For instance, nouns such as ainaka'si ‘wagon’ belong to the grammatically animate noun class. All grammatically animate nouns use the same plural marking –iksi, as in saahkomaapi-iksi ‘boy-s’ and ainaka'si-iksi ‘wagon-s’. Grammatically inanimate nouns such as napioyis ‘house’ use a different plural marking from grammatically animate nouns; that is, -istsi, as in napioyis-istsi ‘house-es’.

Unlike grammatical animacy, semantic animacy refers to real-world animacy. A human or animal is viewed as semantically animate, but an object or a thing is not. Among the semantically animate nouns, those that have the ability to sense or perceive (Speas and Tenny 2003) are referred as sentient nouns in the literature on Blackfoot, as mentioned in section 1. In previous studies, only sentient nouns are shown to play important roles in various parts of Blackfoot syntax (e.g., Bliss Reference Bliss and Christoph Wolfart2007; Meadows Reference Meadows2010; Ritter and Rosen Reference Ritter, Rosen, Rappaport-Hovav, Doron and Sichel2010; Kim Reference Kim2014b, Reference Kim2015b, Reference Kim and Macaulay2017, Reference Kim, Macaulay and Noodin2018; Wiltschko and Ritter Reference Wiltschko and Ritter2015). Wiltschko and Ritter (Reference Wiltschko and Ritter2015) suggest that the aforementioned studies show that only sentient arguments are visible to narrow syntax. By providing novel evidence from motion verbs, the present article makes the significant contribution that event delimitedness in the Blackfoot language is also sentient-oriented.

The grammatically animate class in Blackfoot includes both sentient nouns and some non-sentient ones, while the grammatically inanimate class includes non-sentient nouns only. For instance, in Blackfoot, the noun ainaka'si ‘wagon’ is semantically inanimate and non-sentient, but it is grammatically animate.

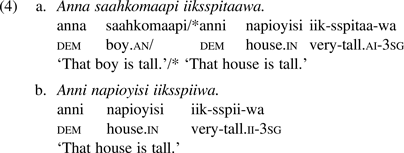

Grammatical animacy of a subject or an object in Blackfoot is morphologically reflected in a verbal suffix called a final. Final morphemes in Blackfoot are suffixes to a root verb; they indicate the grammatical animacy of the subject (S) or the object (O) as well as the transitivity of the verb (Frantz Reference Frantz2009). Throughout this article, (in)animate refers to grammatical (in)animacy (as opposed to non-sentience). The forms of the finals vary according to the verb that they attach to and are often not easily separable from a verb. In many cases, the forms of the finals are suppletive. To illustrate, consider the data in (4). The verb sspitta ‘tall’ in (4a) is in an Animate Intransitive (henceforth AI) final form, which indicates that the verb is intransitive and the subject noun is animate. The animate DP ‘that boy’ in (4a) can appear as a subject, but the inanimate DP ‘that house’ is not allowed as the subject of the AI verb. A grammatical example of the inanimate DP ‘that house’ as a subject is shown in (4b) with a corresponding Inanimate Intransitive (henceforth II) verb sspii.

There are four types of finals in Blackfoot (Frantz Reference Frantz2009) including AI and II forms, like other Algonquian languages (see Bloomfield Reference Bloomfield, Hoijer and Osgood1946). As motion verbs in Blackfoot discussed in this article are all AI verbs (see section 4), I do not discuss the other two types of finals: finals that indicate that the verb is transitive, and those who indicate the grammatical animacy of the object.Footnote 7

The number and person suffixes on the verb in Blackfoot cross-reference arguments of the verb. For example, in (4), the suffix –wa on the AI verb ‘tall’ indexes the third person singular subject. Furthermore, for intransitive verbs such as AI or II verbs, only a 3rd person subject is indexed on the verb as a suffix; for instance, first person is not indexed on the verb as a suffix. This article does not discuss these suffixes or the differences between 3rd and other persons with respect to the indexing on the verb, as they are not relevant to the issues, such as delimitedness or VP, that are discussed in this article.

4. Sentience, delimitedness, and motion events

In this section, I demonstrate that a goal PP in Blackfoot only occurs when an initiator is present, supporting the proposal that aspect in Blackfoot is initiator-oriented. I show that Blackfoot is a type of I-language where an initiator is an agent, and that this initiator must be sentient.

4.1 Inherently directed vs. manner of motion verbs with a PP

The central proposals discussed in this article stem from the existence of two types of motion verbs in Blackfoot: a) inherently-directed motion verbs such as ‘go’, ‘descend’, or ‘climb’ and b) manner-of-motion verbs such as ‘roll’ (in the sense of Levin Reference Levin1993). The main goal of this section is to establish basic properties and structures of those two types of motion verbs along with verbal prefixes associated those verb types, building on the works of Kim (Reference Kim, Iyer and Kusmer2014a, Reference Kim2015a, Reference Kimb). In the discussion to follow, inherently-directed motion verbs are referred as go-type verbs, and the manner verbs are referred to as roll-type verbs. In Blackfoot, go-type verbs such as ‘come’, ‘descend’, ‘ascend’ or ‘climb’ are expressed by the root verb oo ‘go’ prefixed with a direction prefix; for example, waamis-oo (up-go) ‘ascend/climb’ (see (4a)) or sainnis-oo (down-go) ‘descend’. In this article, I illustrate examples of go-type verbs with the verb oo ‘go’.

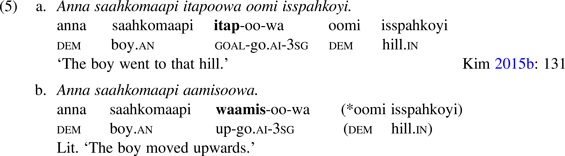

Before discussing the go- and roll-type motion verbs central to the analysis, I discuss the use of two different types of verbal prefixes that appear with these motion verbs (Frantz and Russell Reference Frantz and Russell1995; Kim Reference Kim2015a, b). The first is a goal prefix itap- ‘to’ and the second is one of a large set of direction prefixes. The goal introduces a goal DP only when it is prefixed to a go-type verb (so not with a roll-type verb; see discussion of example (6b)). By contrast, a direction prefix indicates only a direction and cannot introduce a goal DP. An example of each type is illustrated in (5a) and (5b) respectively, with the go-type verb oo ‘go’:

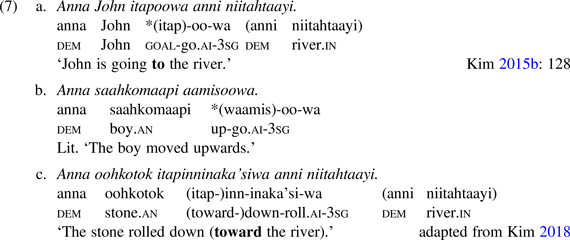

In (5a), the prefix itap- has a goal meaning ‘to’ and introduces the endpoint oomi isspahkoyi ‘that hill’ to the motion event.Footnote 8 An endpoint introduced by the prefix itap- can be omitted (see (7)). In contrast, in (5b), a direction prefix waamis- ‘up’ appears on the verb, and as indicated in the example, it cannot introduce a goal of the direction such as ‘that hill’. Following the previous literature, I assume that the prefixes like those in (5) appearing with motion verbs instantiate a P head (Frantz Reference Frantz2009, Kim Reference Kim, Iyer and Kusmer2014a).

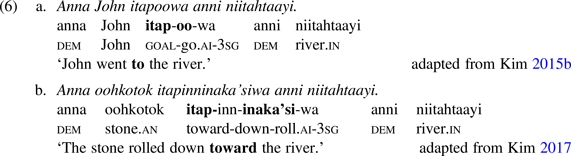

As discussed earlier, the P itap- has a goal meaning when it is prefixed to a go-type verb. However, when prefixed to a roll-type verb, it is shown to have a direction (‘toward’) meaning, but not a goal meaning (Kim Reference Kim2015b), similar to ‘toward’ in English (Jackendoff Reference Jackendoff1983). For example, in a go-type motion verb (6a), an itap PP indicates a goal, giving rise to a delimited meaning of the event: the event ‘going to the river’ is completed when John has reached ‘the river’.

On the other hand, the prefix itap- merely indicates a direction ‘toward’ when it appears with a roll-type such as inaka'si ‘roll’, as illustrated in (6b). In this case, itap- introduces a DP ‘the river’ which indicates only a direction of the motion denoted by the verb, supported by the fact that the event of ‘rolling’ in (6b) is considered to be non-delimited. The event took place ‘toward’ the river, but it is not specified whether the event has been completed there. Kim (Reference Kim2015b) proposes that this difference in delimitedness arises from two different meanings of itap-, modelled on the differences between ‘to’ (delimited) and ‘toward’ (non-delimited) proposed for English in Jackendoff (Reference Jackendoff1983). For now, I adopt this proposal. In section 4.3, however, I show that the difference in delimitedness between the two different meanings of itap- is borne out by Blackfoot-specific evidence, providing language-specific diagnostics to determine whether an itap-PP denotes a goal or a direction. Importantly, building on the results of diagnostics, I demonstrate in section 4.4 that only a goal itap-PP such as in (6a) contributes to event delimitation, and only when a sentient initiator is present.

Another thing to note is that to a roll-type verb as in (6b) obligatorily requires a direction prefix such as inn- ‘down’ that cannot introduce a DP, the locus of the direction, like waamis- ‘up’ in (5b). The sentence is ungrammatical without this type of direction prefix, even if the direction P itap- is present (*itap-inaka'si-wa anni niitahtaayi.).

The two types of motion verbs also differ in that go-type motion verbs require either a goal itap-P, as shown in (7a), or a direction prefix, as in (7b). This is true even when the goal DP introduced by the itap prefix is omitted, as in (7a). In contrast, with roll-type motion verbs, a direction itap-PP (both the prefix and DP) is optional, as shown in (7c) (Kim Reference Kim2015b).

Following Kim (Reference Kim, Iyer and Kusmer2014a, Reference Kim2015b) and as also assumed for similar types of PPs in other languages (Baker Reference Baker1996, Tungseth Reference Tungseth2008), I assume that obligatory goal PPs are internal to the VP (similar to an object), while optional goal PPs are adjuncts.Footnote 9 Thus, the itap-PP can be treated as an argument of the go-type motion verb in (7a), but an adjunct to the roll-type motion verb in (7c). Note that this distinction does not mean that an itap-PP has the same syntactic properties (such as an agreement) as the object of a transitive verb in the language (see relevant discussion in section 4.4).

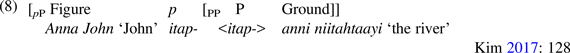

The proposals made later in this section are built on the structure of itap-PP as proposed in Kim (Reference Kim, Iyer and Kusmer2014a) whose analysis adopts the widely held proposal that a spatial P has an extended projection such as p (e.g., van Riemsdijk Reference van Riemsdijk, Pinkster and Genee1990, Rooryck Reference Rooryck, Thráinsson, Epstein and Peter1996, Svenonius Reference Svenonius2003 among others). The structure is illustrated in (8).

In (8), itap- instantiates P which moves to a functional p. The head p introduces a Figure in its specifier, and a Ground as a complement PP. A Figure is an entity in motion or an entity that is located with respect to the Ground (Talmy Reference Talmy and Shopen1985). The Ground is a location of the Figure. For instance, in (8), ‘John’ is a Figure in motion occupying the specifier of pP. The DP ‘the river’ is the Ground where the Figure ‘John’ is located, and it occupies the complement of P.

Table 1 summarizes the distribution of the two different types of motion verbs with respect to the verbal prefixes discussed in this section. There are two types of prefixes: (i) an itap- prefix that can indicate either a goal or a direction and (ii) a direction prefix. The former introduces a DP of goal or direction, while the latter cannot introduce a DP goal or direction (not indicated in the Table below). Regarding the obligatoriness of these prefixes, go-type verbs require one of the two, but not both.

Table 1: Two types of AI motion verbs with respect to verbal prefixes

4.2 Sentience, a goal phrase, and feature [m(ental state)]

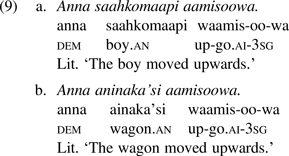

The motion verbs in Blackfoot discussed in this article belong to the AI class, meaning that the subjects of the motion verbs are animate but can be either sentient or non-sentient (see section 3).Footnote 10 This is illustrated in (9a) and (9b): the animate subject, saahkomaapi ‘boy’, in (9a) is sentient, and the animate subject, ainaka'si ‘wagon’, in (9b) is non-sentient. Note that go-type motion verb oo ‘go’ is prefixed with direction prefix waamis ‘up’ in both cases of (9). These examples show that with a direction prefix, a go-type verb can appear with either a sentient or non-sentient subject.

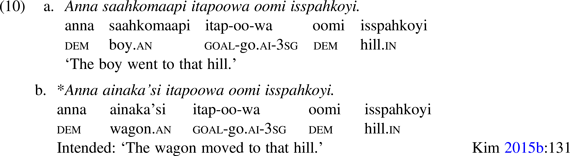

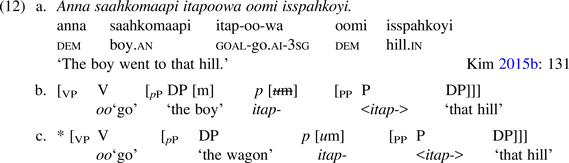

On the other hand, go-type motion verbs impose a sentience restriction on their subjects when they appear with a goal prefix itap- (Kim Reference Kim2015b), as shown in (10). In (10a), the subject is a sentient DP ‘the boy’ and the goal is ‘that hill’ introduced by itap-. However, the utterance becomes ungrammatical when the subject is switched to a non-sentient but animate DP ‘that wagon’ as in (10b).

Building on Kim (Reference Kim, Iyer and Kusmer2014a, Reference Kim2015a, Reference Kimb), this article shows that the sentience restriction exhibited by go-type motion verbs as in (10) is required only when a goal pP appears, as shown by the fact that the non-sentient subject ‘wagon’ is grammatical with the same type of motion verb in the absence of a goal pP, as illustrated in (9b). The contrast between (9) and (10) suggests that a go-type motion verb requires a sentient subject in order to indicate an endpoint of an event, that is, a goal of motion.

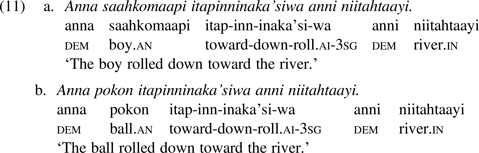

The current article further provides new data on roll-type motion verbs. The properties of roll-type motion verbs are significant to the core proposal of this article, as a roll-type verb shows a contrast from a go-type verb with respect to sentient subjects. With a roll-type motion verb, subjects are not required to be sentient, in contrast to a go-type motion verb. As illustrated in (11), for instance, either a sentient DP ‘the boy’ (11a) or a non-sentient DP ‘the ball’ (11b), both of which are animate, can appear as a subject of the AI verb ‘roll’ (the meaning of the subject of a roll-type verb will be shown in section 4.4). Note that without direction itap-pP, optional with a roll-type verb, the sentences in (11) are grammatical.

Summarizing the data thus far, the sentences in (9)–(10) show that a go-type motion verb can indicate a goal of motion via itap-pP only when its subject is a sentient DP. With a roll-type motion verb as in (11), itap-pP indicates direction of motion, and there is no sentience restriction on the subject. The sentience restriction on the subject imposed by different motion verbs is summarized in Table 2 below.

Table 2: Sentience restriction in the motion verbs

I propose that the sentient property of an argument in Blackfoot is represented by the feature [m(ental state)] (Reinhart Reference Reinhart2002) in line with Ritter (Reference Ritter2015) and Wiltschko and Ritter (Reference Wiltschko and Ritter2015).Footnote 11 In Reinhart (Reference Reinhart2002), the feature [m] represents a sentient participant whose mental state is relevant to the event such as those indicated by VPs, which can be either agentive or non-agentive (e.g., an experiencer). It is important to keep in mind that sentience represented by an [m] feature indicates that an argument it indexes is a mental state holder; but the feature itself does not imply agency.Footnote 12 A DP with [m] feature in Blackfoot is indexed as a sentient DP, not necessarily as an agent DP. In the next section, a sentient subject that licenses a goal pP (e.g., a subject of a go-type verb) is shown to be an agent, in contrast to a sentient subject that cannot license a goal pP (e.g., a subject of a roll-type verb).

In Blackfoot, as shown by the contrast between (9) and (10), only a sentient subject of a go-type motion verb allows a goal pP; a non-sentient subject does not. I propose that a goal p requires a sentient argument in its specifier; that is, in terms of the feature [m], the specifiers of goal p require a DP that bears the feature [m]. The current proposal on the sentience restriction of goal pP shown with the motion verbs is in line with the configurational property of Blackfoot proposed in Wiltschko and Ritter (Reference Wiltschko and Ritter2015) in which a certain set of functional heads in the language requires a sentient argument in its specifiers.

In the domain of the motion verbs discussed in this section, the relevant functional head that requires a sentient DP is a goal p, and the p required by a go-type motion verb imposes a restriction on its specifier to be filled with a DP, that is, a DP with the [m] feature. Following Ritter (Reference Ritter2015), I assume that a sentient DP is in a selectional relationship with a relevant functional head in terms of a feature-checking relation, as schematically illustrated in (12b) below.Footnote 13 Implementing this assumption for go-type motion verbs, I propose that a head p realized by itap- bears an uninterpretable [m] feature, [um], which is in feature-checking relation with [m] on a sentient DP that merges in its specifier, as illustrated in (12b). If, instead of a sentient DP ‘that boy’, a non-sentient DP such as ‘the wagon’ appears in the specifier of pP, as in (12c), the derivation crashes, as it does not have the feature [m] to check [um] on p. The contrast between the derivations in (12b) and (12c) captures the fact that with go-type motion verbs, only a sentient argument allows a goal pP.

In the next two sections, I further develop the proposed structure of the go-type motion verbs in (12b). I demonstrate that this structure is associated with delimitedness, made available by a sentient initiator, in contrast to the structure of roll-type motion verbs.

4.3 Delimitedness in motion verbs

In this section, I provide Blackfoot-specific evidence to show that an itap-pP yields a delimitedness interpretation of a motion event when it expresses a goal meaning, but not when it expresses a directional meaning. That is, an itap-pP that expresses a goal meaning can indicate that an event has reached a final point such that the event is completed, unlike an itap-pP that expresses a directional meaning. It is important to keep in mind that the delimitedness interpretation of itap-pP is visible only when a sentient initiator is present, as will be shown in section 4.4. The difference in meaning between the itap-pPs has been assumed in |Kim (Reference Kim2015b, Reference Kim and Macaulay2017) relying on English data in Jackendoff (Reference Jackendoff1983).

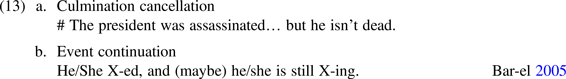

Novel evidence for Blackfoot provided in this section builds on two diagnostics that identify whether an endpoint of a predicate is semantically present or not, like the diagnostics used in previous studies (e.g., Matthewson Reference Matthewson2004, Bar-el Reference Bar-el2005, Bar-el et al. Reference Bar-el, Davis, Matthewson, Bateman and Ussery2005, Travis Reference Travis2010). Before the discussion of new evidence from Blackfoot that is the central part of this article, I provide some background on these diagnostics from the previous studies. The two tests are: (i) culmination cancellation, and (ii) event continuation, from Bar-el (Reference Bar-el2005). These tests are illustrated in (13a) and (13b) respectively.

A culminated event has an inherent endpoint, which suggests that it is delimited. For example, in (13a), the first conjunct expresses a culminated event, assassination of the president. If the culminated portion of the event is an entailment, cancelling the portion results in a contradiction, as shown by the second conjunct in (13a), which cancels the assassination of the president, resulting in a contradiction (indicated by #). In this way, the culmination cancellation test shows whether the event in question has an endpoint. The event continuation test in (13b) indicates whether the event in question is ongoing or not. An ongoing event can be continued with a progressive phrase, while a delimited event is incompatible with such a continuation, suggesting that it has an endpoint. For these diagnostics to work, the event in question (in the first conjunct, as in (13)) should be expressed as a perfective (e.g., see Bar-el Reference Bar-el2005). Following Dunham (Reference Dunham and Deal2007) and Armoskaite (Reference Armoskaite, Hele and Darnell2008), I assume that bare forms or past tense forms (as identified in Frantz Reference Frantz2009) in Blackfoot have perfective interpretations. Thus, the verbs used to set up the tests (i.e., the verbs in the first conjuncts) in Blackfoot are expressed in one of these forms.Footnote 14

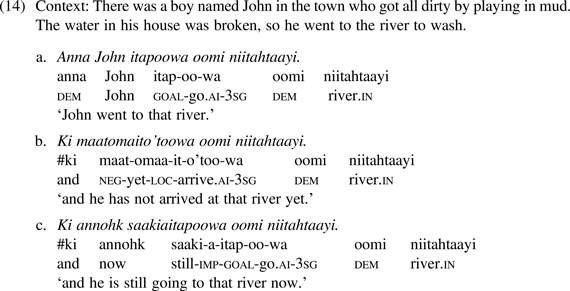

In what follows, I provide novel evidence from Blackfoot by discussing how diagnostics such as those in (13) figure when applied to the motion verbs discussed in the previous sections. The results of the tests show that delimitedness interpretation of an itap-pP is possible only when it appears with go-type, but not with roll-type motion verbs. First, consider the results of the two tests applied to a go-type motion verb, as in (14). In the examples to follow in this section (and the rest of the article), a relevant context for the examples is provided as a non-aligned first line in each of the examples.

Given the context in (14), consultants were asked whether (14b) or (14c) can follow the sentence in (14a). An event associated with go-type motion verbs with an obligatory goal pP is compatible with neither culmination cancellation (14b) nor event continuation (14c). In particular, note that the sentence in (14c) includes the adverb annohk ‘now’ which supports the ongoing reading of the imperfective a-, but rules out a habitual reading of the imperfective, as proposed for Blackfoot in Dunham (Reference Dunham and Deal2007). Moreover, the provided context also rules out a habitual reading of (14c). The incompatibility indicates that an event associated with the go-type motion verb cannot be understood as ongoing, having an inherent endpoint indicated by an itap-pP. Taking the result of these tests as evidence, I propose that the itap-pP that appears with this type of the verb indicates a goal meaning. It will be shown in the next section that a goal meaning of itap-pP is visible only when an initiator is available.

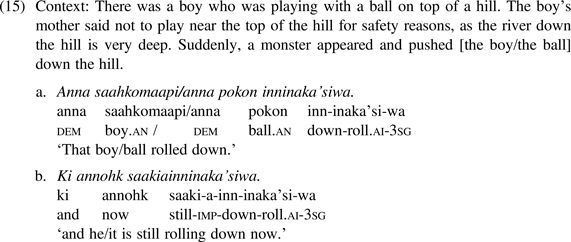

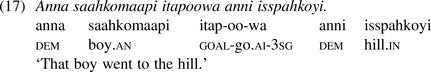

With respect to the same tests, roll-type motion verbs show contrast with the go-type in (14). Consider first the result of the tests with the roll-type motion verb. Recall that this type of verb allows an optional itap- phrase with directional meaning. When a direction itap- phrase is not present, as in (15a), an event indicated by this type of verb can be continued with a sentence such as in (15b) indicating that the event is ongoing. The presence of the adverb annohk ‘now’ in (15b) also confirms the ongoing interpretation of (15b).

When an itap- direction phrase is present as in (16) below (where the same context as (15) was provided), the event can also be followed by a sentence that indicates event continuation (16c), which contrasts with the go-type motion verb tested using the same test as in (14c). This contrast between the two types of the verbs suggests that the meaning indicated by an itap- phrase that appears with a roll-type motion verb is not the same as that indicated by go-type motion verb, namely that the event does not include an endpoint. Otherwise, we would observe similar results of the test with both types of verbs. This is further supported by a culmination cancellation test with the roll-type motion verb, shown in (16b) below. This test does not entail a contradiction, in contrast to that of the go-type motion verb shown in (14b). Building on these results, I conclude that the event associated with a roll-type motion verb lacks an inherent endpoint, and that an itap- phrase that appears with this type of the verb indicates a directional rather than a goal meaning.

The data provided in this section suggests that the presence of an itap- goal pP alone is able to delimit an event similar to a goal PP in a D-language such as English (see sections 1 and 2). However, in the next section, I show that an itap- goal pP cannot be treated in the same way as a goal PP in a D-language. I demonstrate that the event delimitedness indicated by a goal pP in Blackfoot is visible only when a sentient DP that is an initiator is present. Importantly, this constitutes strong evidence for Blackfoot being an I-language.

4.4 A delimited event via an initiator

As we saw in section 2, in an event, an I-language can be delimited only when an initiator is available. For instance, since goal pPs can indicate delimitedness of motion events, a prediction is that goal pPs will only be available if the sentence contains a volitional agent who initiates the event. In Blackfoot, a language-specific sentience restriction on external arguments (e.g., Frantz Reference Frantz2009, Johansson Reference Johansson2009) rules out other potential non-sentient candidates for an initiator, such as cause or instrument (see more discussion at the end of this section). If aspect in Blackfoot is sentient initiator-oriented as proposed in this article, a sentient argument with an [m] feature can be the type of agentive DP that can become an initiator.

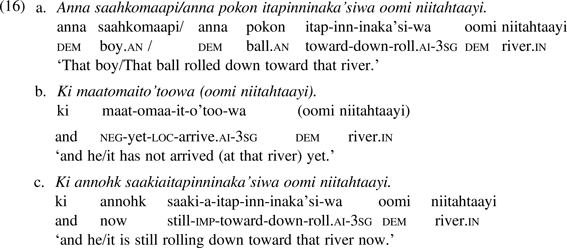

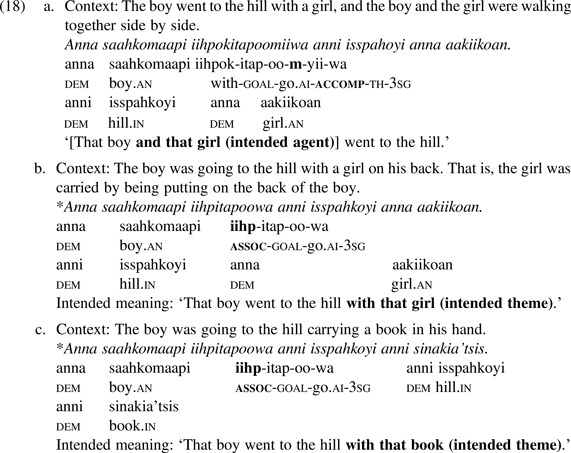

In this section, I show that this prediction is borne out by the contrast between go- and roll-type motion verbs. Specifically, I show that a sentient subject of a go-type motion verb in Blackfoot is interpreted as an agent, which is eligible to be an initiator in the language. In contrast, a sentient subject of a roll-type motion verb can only be interpreted as a non-agent, such as a theme; thus, there cannot be an initiator with this type of verb.Footnote 15 This contrast captures the facts that events associated with go-type motion verbs can license a goal pP, but events associated with roll-type motion verbs cannot. Evidence comes from the fact that a Figure argument of p, a sentient DP, is interpreted as an agent with go-type motion verbs only, but not with roll-type motion verbs. Meadows (Reference Meadows2010) identifies two different morphemes that introduce an argument with a specific role (i.e., either an agent or a theme) in Blackfoot. One is an accompaniment suffix (-m) that introduces a sentient entity that is interpreted as a companion of the agent argument in the sentence.Footnote 16 The other morpheme is an associative prefix (iihp-/ohp- ‘with’) that introduces an entity that is interpreted as an associate of a theme. Unlike an accompaniment suffix, an associate prefix does not impose a sentience restriction on its argument.Footnote 17 As shown by Meadows (Reference Meadows2010) and as will be shown by the data below, a companion and an associate are different in their thematic roles: agent vs. theme. Consider the go-type motion verb that requires a goal pP in (17), and the results of the tests applied to (17) are shown in (18).

I employ the two affixes as tests to identify whether the subject of a motion verb is an agent or a theme.Footnote 18

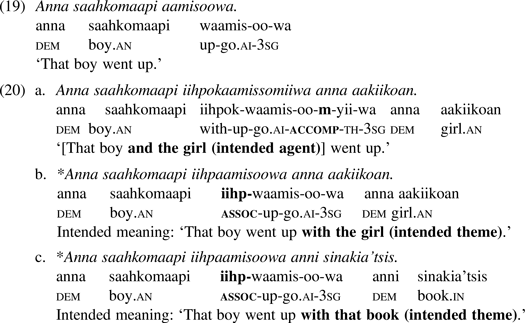

The results of the tests support the hypothesis that the subject of the verb ‘go’ is an agent, as shown by the contrast in grammaticality between (18a) and (18b–c). go-type motion verbs with a goal pP are grammatical with an agent-identifying accompaniment suffix as shown in (18a), but ungrammatical with a theme-identifying associative prefix as in (18b–c). The companion ‘that girl’ in (18a) is an agent, as indicated in the context provided, and in this case, the sentence in (18a) is grammatical, which suggests that the sentient subject ‘that boy’ must be an agent. In (18b–c), the added associates (either sentient ‘that girl’ (18b) or non-sentient ‘that book’ (18c)) are themes in the sense that they were carried by the subject ‘that boy’. In these cases, the sentences in (18b–c) are ungrammatical, which suggests that the sentient subject ‘that boy’ in (18b–c) cannot be a theme.

Recall that go-type motion verbs without a goal pP allow either a sentient or non-sentient subject (see Table 2). Interestingly, go-type motion verbs without an overt goal pP exhibit different behaviour with respect to the two affixes, depending on whether the subject is sentient or non-sentient. An example of a sentient subject with no goal phrase is illustrated in (19); the result of the two tests with (19) is shown in (20). An example of a non-sentient subject with no goal phrase is illustrated in (21a) and the result of the two tests with (21a) is shown in (21b–d). For the sentences in (20), the contexts given were the same ones used for the sentences in (18).

The sentient subject in (19) is compatible with an accompaniment suffix, as shown in (20a), but is incompatible with an associate prefix that identifies a theme, as shown in (20b–c). The grammaticality with an accompaniment suffix as in (20a) suggests that a sentient subject of go-type motion verbs without a goal pP must be an agent. The ungrammaticality with an associate prefix as shown in (20b–c) further supports this conclusion: regardless of the sentient status of the associates (20b) or (20c), the sentences remain ungrammatical. That is, a sentient subject of go-type motion verbs without a goal pP cannot be a theme.

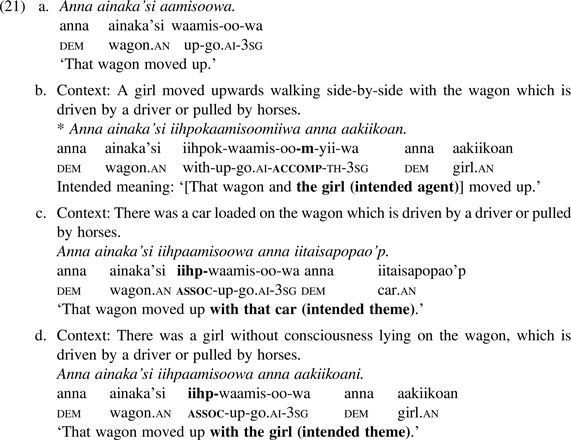

In contrast, the same verb without a goal phrase but with a non-sentient subject in (21a) shows the opposite, with respect to the two affixes. It is incompatible with an agent-identifying accompaniment suffix (21b), but is compatible with a theme-identifying associate prefix (21c). In (21b), ‘the girl’ is an agent, as indicated by the context. However, as the ungrammaticality with accompaniment suffix in (21b) shows, a non-sentient subject ‘that wagon’ cannot be treated as an agent.

In (21c), with a non-sentient associate ‘that car’, the sentence is grammatical in the context provided, where the car is treated as a theme, confirming that a non-sentient subject of a sentence such as in (21a) is a theme. As for a sentient associate such as ‘that girl’ in (21d), a similar result was observed. The associate ‘that girl’ is understood to be non-conscious (e.g., being unconscious or dead (an extreme case)), as suggested by the provided context. In this context, ‘the girl’ and ‘that wagon’ are moved together (i.e., themes). Thus, ‘the girl’ in this case is treated as a non-sentient entity just like ‘that car’. The result of the test in (21) supports the proposal that a non-sentient subject of a go-type motion verb without a goal pP must be a theme, not an agent.

The following table summarizes the role of a subject of a go-type motion verb. It also shows the result of the tests with roll-type motion verbs that is discussed below. Regarding the go-type verbs, a fourth logical possibility would be a case of a non-sentient subject with a goal pP. However, as we have seen, this possibility is ruled out by the sentience restriction on this type of verb, and for this reason it is not included in Table 3.

Table 3: Summary of the agent- and theme-identifying tests

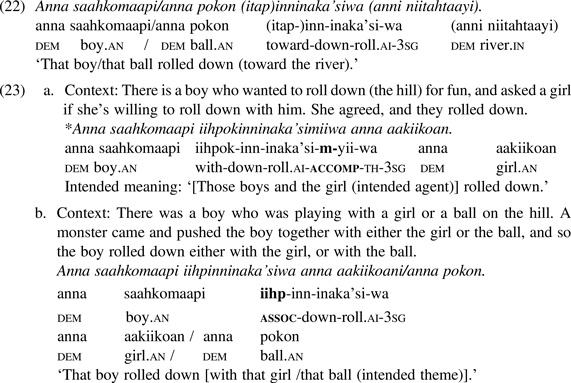

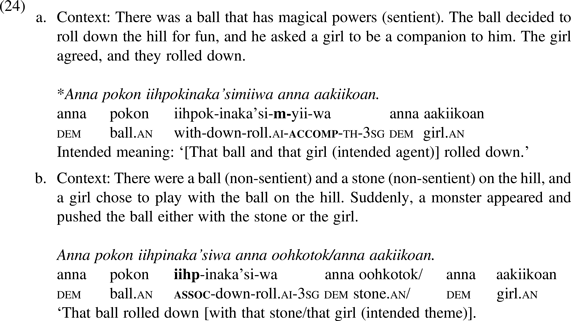

When the same tests are applied, a roll-type motion verb contrasts with the go-type, as indicated in Table 3. The verb behaves in the same way with the two morphemes, regardless of sentient status of the subject or of the presence of optional pP indicated by brackets: the subject of a roll-type verb is always a theme. Evidence is provided in data (23)–(24) below based on the sentence in (22). As shown in (22), the verb ‘roll’ allows either a sentient ‘that boy’ or non-sentient subject DP ‘that ball’, and itap- on the verb can indicate direction optionally. Regardless of the sentience of the subject, this verb is incompatible with an accompaniment suffix that introduces an agent companion, but compatible with an associate prefix that introduces a theme associate. This is shown in (23) with a sentient subject, and in (24) with a non-sentient subject.

The ungrammaticality with accompaniment suffix as in (23a) suggests that the sentient subject of roll-type verb such as ‘that boy’ cannot be interpreted as an agent. In (23a), as indicated by the context, the added companion ‘that girl’ is an agent. However, even in this context, the sentence in (23a) was rejected by the consultants. In contrast, the sentence in (22) is grammatical when it appears with an associate prefix as shown in (23b), which suggests that a sentient subject of the roll-type verb must be a theme. In (23b), unlike in (23a), ‘that girl’ is a theme, as indicated in the context.

With respect to a non-sentient subject ‘that ball’ of the verb ‘roll’ in (22), the same result was observed. With an accompaniment suffix, the result was ungrammatical as illustrated in (24a), just as with a sentient subject of the same verb (23a). In (24a), as indicated in the context, ‘that ball’ was treated as a sentient being having magical powers. However, a sentence such as (24a) was judged to be ungrammatical even in this type of context.

As for (24b) with an associate prefix, a theme context was provided similar to the one given for (23b). In (24b), ‘that ball’ is an ordinary non-sentient ball, as illustrated in the context. The sentence was judged to be grammatical in this type of context. In sum, the result of the tests indicates that the subject of roll-type motion verbs is a theme, regardless of the sentience of the subject without a goal pP endpoint. Although I cannot provide relevant data for reasons of space, the same result is observed when an optional direction pP, itap- ‘toward’, appears with this type of verb.

The data presented in this section demonstrates that subjects of the go-type motion verbs are interpreted as agents only when the subject is sentient, but those with roll-type verbs are interpreted as themes regardless of sentience of the subject.

Moreover, the data in this section shows that only agentive sentient arguments are compatible with a delimited event expressed by a goal pP, while theme sentient arguments are not. Implementing this result into the proposed structure of go-type motion verb in section 4.2 (see (11b)), I propose that an agentive v is projected above the proposed structure of go-type motion verb, as illustrated in (25). In particular, this v has a language-specific property of bearing an [um] feature, supported by the fact that only a sentient argument interpreted as an agent can appear with this type of verb, as shown by the data in (18), and the contrast between (20) and (21).Footnote 19 In (25), thus, v with an [um] feature hosts in its specifier a sentient agent.Footnote 20

I propose that the head v is the locus of initiation in Blackfoot and carries an [initiation] feature (see section 2).Footnote 21 In Blackfoot (an I-language), unlike in an English-type language (a D-language), the delimited interpretation of a goal pP can be activated only when a language-specific initiator appears. I implement this constraint of activating event delimitedness in Blackfoot into the feature [initiation] on a functional head that hosts a language-specific initiator, namely, v[um], as in (25). In other words, in order for the delimitedness interpretation of a goal pP to be visible, the head v has to bear the feature [initiation] so that its sentient-agent argument becomes an initiator.

The relevant derivation in (25) proceeds as follows: a sentient DP in the specifier of pP is interpreted as an agent when it occupies the specifier of vP via movement, to check the feature [um].Footnote 22 Subsequent to this movement, the DP obtains an initiator role via the [initiation] feature on v, and consequently, the delimiting interpretation of the event becomes possible. I assume that the projection goal pP is functionally equivalent to a projection such as FPdelim without invoking a separate FPdelim.Footnote 23

The examples of roll-type motion verbs shown in (22)–(24) suggest that this type of verb does not project an agentive v that hosts a sentient initiator in its specifier, as illustrated in (26).

The lack of such v captures the fact that the subject of a roll-type verb is not an agent, and thus cannot be an initiator, in contrast to that of the go-type motion verb in (25). Lacking an initiator, the event structure associated with roll-type verbs as in (26) cannot license a delimiting phrase such as itap-pP that is a goal.Footnote 24 Even if an itap goal pP were present with roll-type verbs, the derivation would crash as there is no initiator available, as shown by (23a).

Lastly, I would like to discuss an important implication of this article: that aspect, in Blackfoot, is sentience-oriented. It is possible that the association between a sentient subject and a delimited event proposed in this article follows from two factors summarized as follows: (i) AI motion verbs with itap- goal pP have a transitive structure in the sense of Ritter and Rosen (Reference Ritter, Rosen, Rappaport-Hovav, Doron and Sichel2010), and (ii) a sentient subject is required for a transitive structure in Blackfoot. Under this view, a sentient external argument may play no role in event delimitedness, but rather it is a goal pP that delimits an event, similar to English. Thus, the association between a sentient subject and delimitedness of event is coincidence, and aspect in Blackfoot has no difference from aspect of other well-documented languages such as English.Footnote 25

However, this view requires careful examination. Consider factor (i). In Ritter and Rosen (Reference Ritter, Rosen, Rappaport-Hovav, Doron and Sichel2010), transitive verbs in Blackfoot all have a transitive structure in which v has a sentient restriction and licenses a nominal object (e.g., a DP). In particular, the v head in their transitive structure is the locus of the transitive final morpheme, differing in form depending on the grammatical animacy of an object that it licenses; that is, v shows animacy agreement with an object. By contrast, I show that an AI final morpheme on the motion verbs does not have such a relation with an itap- goal pP, although it has sentience restriction. Furthermore, it has been shown that the argument introduced by an itap- type prefix in Blackfoot lacks typical properties of grammatical objects licensed by a transitive final morpheme such as agreement (e.g., Frantz Reference Frantz2009, Kim Reference Kim2020), and the study in Kim (Reference Kim2020) shows that it cannot be treated as an object of transitive verbs. Thus, I conclude that AI motion verbs do not have a transitive structure in the sense of Ritter and Rosen (Reference Ritter, Rosen, Rappaport-Hovav, Doron and Sichel2010). Hence, the sentience restriction on motion AI verbs with itap- goal pP shown in this article does not follow from the second factor in (ii), that is, for sentience requirement for a transitive structure in Blackfoot.

With this conclusion, it cannot be said that the association between sentience restriction and event delimitedness proposed for AI motion verbs is a coincidence. Neither can it be concluded that event delimitedness in Blackfoot is expressed by a goal pP as is the case in English.

If so, what we are left with is the data of motion AI verbs and their implications. In particular, as shown in this section, all inherently-directed motion verbs – go-type verbs with a goal pP – show this type of association. In contrast, roll-type motion verbs cannot be delimited, as they do not have an agent that can be an initiator. With this type of verb, even if a sentient argument merges in the specifier of pP, the sentient argument fails to be an initiator; that is, the presence of a goal pP with a sentient argument is not sufficient for event delimitedness. This contrast between go-type and roll-type motion verbs is accounted for by the proposed structural differences between the two types of verbs (see (25) vs. (26)): the presence and absence of v[um]. These differences between the two types of verb indicate that a sentient subject plays an important role in Blackfoot aspect, which in turn suggests that aspect in Blackfoot cannot pattern the same way as English-type aspect. Although a delimitedness interpretation may be indicated by a goal pP, the interpretation can be visible only when an initiator is present (via v[um]).

5. Conclusion

I have provided a detailed linguistic description of how delimitedness of a motion event is associated with a sentient external argument in Blackfoot, and demonstrated that such a sentient argument is an agent that can be an event initiator. I have also provided a formal analysis of the association between a sentient initiator and event delimitedness. That Blackfoot has a sentient initiator-oriented aspect thus offers novel support to the current view in the literature about Blackfoot wherein Blackfoot grammar is sentience-dominant (e.g., Louie Reference Louie2008, Frantz Reference Frantz2009, Johansson Reference Johansson2009, Meadows Reference Meadows2010, Ritter and Rosen Reference Ritter, Rosen, Rappaport-Hovav, Doron and Sichel2010, Bliss Reference Bliss2013, Kim Reference Kim2014b, Ritter Reference Ritter2015, Wiltschko and Ritter Reference Wiltschko and Ritter2015).Footnote 26

The result emerging from this study indicates that initiation is not merely a component of event structure, but can have a more dynamic role in some languages, as shown by Blackfoot. For example, an initiator in Blackfoot is involved in the determination of event delimitedness, which has traditionally been considered as being affected only by certain types of internal arguments such as a goal PP or an incremental theme object (e.g., Vendler Reference Vendler1967; Dowty Reference Dowty1979; Tenny Reference Tenny1987; Borer Reference Borer2005; Ramchand Reference Ramchand2007; MacDonald Reference MacDonald2008a, Reference MacDonaldb). Thus, the present article provides a crucial step toward understanding the organization of an initiation-oriented aspect, which paves the way for further study on related issues dealing with aspect.