1. Introduction

A growing body of work explores the role of information structure on word order variation and change.Footnote 1 Information structure refers to the way languages structure discourse information like topic and focus. The cartographic approach to syntactic structures (e.g., Rizzi Reference Rizzi and Haegeman1997, Reference Rizzi2004; Cinque Reference Cinque2002, Reference Cinque2006; Cinque and Rizzi Reference Cinque and Rizzi2008), despite its shortcomings (van Craenenbroeck Reference van Craenenbroeck and van Craenenbroeck2009), has shown that specific positions in the clause appear to be dedicated to topic and focus elements (Benincà Reference Benincà, Cinque and Salvi1999, Reference Benincà, Zanuttini, Campos, Herberger and Portner2006; Belletti Reference Belletti and Rizzi2004; Benincà and Poletto Reference Benincà, Poletto and Rizzi2004; Benincà and Munaro Reference Benincà and Munaro2010), and a number of authors argue that changes in word order reflect changes in the way a language expresses these notions (e.g., Benincà Reference Benincà, Zanuttini, Campos, Herberger and Portner2006; Laenzlinger Reference Laenzlinger2006; Hinterhölzl Reference Hinterhölzl, Hinterhölzl and Petrova2009; Hinterhölzl and Petrova Reference Hinterhölzl and Petrova2009, Reference Hinterhölzl and Petrova2010; Kroch and Santorini Reference Kroch and Santorini2009; and the various papers in Batllori and Hernanz Reference Batllori and Hernanz2011).

The present article was spurred by Rinke and Meisel's (Reference Rinke, Meisel, Kaiser and Remberger2009) claim that Old French is not a V2 language, and more specifically, that it differs from German in the structuring of information structure. These authors develop an analysis in which Old French, contrary to German, is a topic-initial language. We undertook the task of verifying their claims by studying the informational role of preverbal elements and postverbal subjects in Old French V1 and V2 structures. Our research refutes Rinke and Meisel's analysis. We show that the distribution of Old French preverbal elements is similar to that of typical V2 languages like German. However, as discussed in section 7, we observed an evolution in the statistical distribution of preverbal constituents which suggests that the use of the left periphery changed during the period considered.

2. The Corpus

The data are extracted from 19 parsed Old French texts of the MCVF corpus (Martineau et al. Reference Martineau, Hirschbühler, Kroch and Morin2010) and the Penn supplement to this corpus (Kroch and Santorini Reference Kroch and Santorini2012) (see Appendix). In order to be able to create tables and figures, a date of composition was assigned to each text, ensuring that no two texts had the same date. These dates should, of course, be taken only as an approximation of the year the text was written.

We used Corpus Search (Randall Reference Randall2005) to automatically extract all positive declarative matrix clauses with a full subject (i.e., excluding null and clitic subjects) and to code the data. We report here our analysis of V1 and V2 clauses only. V ≥ 3 clauses were kept for later investigation.

One characteristic of the corpus used is that the 12th-century texts are all in verse except for those of Li Quatre Livre des Reis, 1170 (henceforth QLR). This is due to the lack of 12th-century prose texts, all surviving texts of some length being in verse. Conversely, all of the 13th-century texts in the corpus are in prose, with the unfortunate consequence of a near conflation of text genre and time variables.Footnote 2 In the figures to be presented, both the date and the genre are indicated.

3. Operational Definitions Relative to Information Structure

The following operational definitions of topic and focus are adopted:

Information topic: The information topic, or I-topic, also called aboutness topic (Reinhart Reference Reinhart1981), is the subject of discourse, the entity on which the comment is predicated. It corresponds to “the entity or set of entities under which the information expressed in the comment constituent should be stored in the [common ground] content” (Krifka Reference Krifka2008), the common ground being the information shared by the discourse participants. The I-topic is a discourse-old entity, already present in the discourse or accessible in the common ground, and it is therefore typically a definite constituent. This notion corresponds to Vallduví’s (Reference Vallduví1993) link.

Information focus: The notion of information focus, or I-focus, is linked to the pragmatic principle of Progression (e.g., Charolles Reference Charolles1978) stating that if a sentence is to be informative, it must contain new material. The I-focus of the sentence is brand-new information that enriches the common ground. It is both discourse-new and hearer-new. Thetic sentences are all-focus sentences, that is, sentences containing only new information. In the dialogue in (1), the answer is all-focus.

(1) What happened?

The telephone rang.

An I-focus is not necessarily a contrastive focus, which corresponds to “material which the speaker calls to the addressee's attention, thereby often evoking a contrast with other entities that might fill the same position” (Gundel and Fretheim Reference Gundel, Fretheim, Horn and Ward2004; Krifka Reference Krifka2008). A contrastive focus may be marked by position, by prosody, or by expressions like even, only, and also.

According to Gundel and Fretheim (Reference Gundel, Fretheim, Horn and Ward2004), the notions of I-topic and I-focus correspond to relationally given/new information respectively, and are equivalent to the notions of theme/rheme, or topic/comment. This is largely correct, with some caveats: the comment may contain background, discourse-old, information (shared information that is already in the common ground) in addition to new information (the I-focus per se). For example, in (2), taken from Krifka (Reference Krifka2008: 42, ex. 41), married her in (2b) is background information within the comment (Büring Reference Büring, Ramchand and Reiss2007: 5; Vallduví’s Reference Vallduví1993 tail).

(2) a. When did [Aristotle Onassis]I-topic marry Jacqueline Kennedy?

b. [He]I-topic [married her [in 1968]I-focus]]Comment

4. Old French Information Structure and the Verb Second (V2) Problem

Since the end of the 19th century, it has been observed that the Old French finite verb tends to be found in the second position in main clauses: when an element precedes the verb, the subject is postverbal (Thurneysen Reference Thurneysen1892, Foulet Reference Foulet1928, Skårup Reference Skårup1975). Accordingly, many authors analyze the Old French clause with the V2 structure typical of Germanic languages, as shown in (4) (e.g., Adams Reference Adams1987, Reference Adams1988; Roberts Reference Roberts1993; Platzack Reference Platzack, Battye and Roberts1995; Vance Reference Vance, Battye and Roberts1995). In the Government and Binding framework, the verb was assumed to occupy C and the preverbal constituent [Spec,CP]. With the development of an articulated left periphery (Rizzi Reference Rizzi and Haegeman1997), the verb tends to be analyzed as filling Fin, with the preverbal constituent occupying [Spec,FinP] or a higher position (see Holmberg Reference Holmberg, Kiss and Alexiadou2015 for a review; see also Ledgeway Reference Ledgeway2008, Labelle and Hirschbühler Reference Labelle, Hirschbühler, Mathieu and Truswell2017, Zaring Reference Zaringthis issue). [Spec,CP] (or [Spec,FinP]) corresponds to Skårup's (Reference Skårup1975) place du fondement, or the Vorfeld in German.

(3) messe e matines ad li reis escultet

mass and matins has the king heard

‘The king has attended mass and matins.’ (1100, Roland 11;139)Footnote 3

(4) [CP/FinP messe e matines ad [TP li reis ad escultet messe e matines]

This V2 analysis has been challenged by a number of authors, in part because V1 and V3 constructions are more frequent in Old French than in either modern German (Kaiser Reference Kaiser2000, Reference Kaiser2002; Ferraresi and Goldbach Reference Ferraresi and Goldbach2002; Rinke and Meisel Reference Rinke, Meisel, Kaiser and Remberger2009; Kaiser and Zimmermann Reference Kaiser, Zimmermann, Rinke and Kupisch2011) or Middle High German (1050–1350) (Elsig Reference Elsig2009). Rinke and Meisel (Reference Rinke, Meisel, Kaiser and Remberger2009), for instance, argue, on the basis of a study of two early 13th century texts (Villehardouin and Les 7 sages de Rome), that Old French is not a V2 language but a topic-initial language. They derive Old French matrix clauses within TP, with [Spec,TP] a topic position. The main claim of Rinke and Meisel is that the preverbal position hosts the aboutness topic – I-topic in our terms – and the verb phrase contains the I-focus portion of the clause. Old French is said to differ from contemporary German, where the preverbal position is not restricted to topics but may also host an I-focus or an adverb that is neither a topic nor (part of the) I-focus. If their analysis proves correct, Old French would be similar to Old High German, given Hinterhölzl and Petrova's (Reference Hinterhölzl and Petrova2010, Reference Hinterhölzl, Petrova, Chiarcos, Claus and Grabski2011) claim that the Old High German verb served to separate the I-topic from the comment.

For Rinke and Meisel (Reference Rinke, Meisel, Kaiser and Remberger2009: 109), subjects move to the preverbal position to avoid being interpreted as I-focus: “An incompatibility of the post-verbal subject with an interpretation as information focus or as part of a thetic sentence would cause the subject to move to the pre-verbal position.” This claim would be disproved if the I-topic of the clause may appear postverbally; this is the subject of sections 5 and 6, where postverbal I-topics are shown to be frequent in the corpus.Footnote 4

Scene-setting elements, namely, elements specifying the time and location of the situation under which the proposition is evaluated, are often considered to be types of topics (Speyer Reference Speyer, Shaer, Frey and Maienborn2004: 534–535). Their discourse role, however, differs from that of I-topics, and the two types of elements may co-occur in a clause (Nikolaeva Reference Nikolaeva2001; Andréasson Reference Andréasson, Butt and King2007), as (5) illustrates.

(5) John had a busy day. At twelve[Scene-setting], he[I-topic] was eating pizza with his brother…

In the following quote, Rinke and Meisel suggest that, in Old French, scene-setting adverbials fill the preverbal position only when no I-topic is overtly realized:

In addition, sentence-initial (scene setting) adverbial phrases may serve a special discourse function. According to Reinhart (Reference Reinhart1981), they can establish discourse cohesion by linking the sentence to the previous discourse. Preverbal adverbial phrases thus fulfill the same discourse function as preverbal topics. These adverbial expressions are therefore frequently found in sentences in which no topic is present that would normally assume the discourse-linking function.

(Rinke and Meisel Reference Rinke, Meisel, Kaiser and Remberger2009: 115)If this is correct, Old French differs significantly from German. In German, a sentence may contain both a scene-setting element and an I-topic, and Speyer (Reference Speyer, Shaer, Frey and Maienborn2004, Reference Speyer, Benz and Kühnlein2008, Reference Speyer, Tanskanen, Helasvuo, Johansson and Raitaniemi2010) established that, in a sentence where both are present, the scene-setting element preferentially occupies the Vorfeld, while the I-topic remains postverbal. Consequently, in section 6.2, we study the informational role of postverbal subjects when a scene-setting element is preverbal. We will see that there are many V2 sentences with a preverbal scene-setting element and a postverbal I-topic subject.

Both in Old French and in German, I-topics are often preverbal. This is expected because they are cohesive devices linking with the previous discourse. According to Speyer's (Reference Speyer, Shaer, Frey and Maienborn2004, Reference Speyer, Benz and Kühnlein2008, Reference Speyer, Tanskanen, Helasvuo, Johansson and Raitaniemi2010) research on German, about 82% of the referential elements filling the Vorfeld in written German are elements establishing a link with the preceding discourse (scene-setting, I-topics, and elements anaphoric with a discourse-old set). The remaining cases include brand-new elements (i.e., I-focus in our terms). Hence, placing the I-focus in clause-initial position is not the dominant option in German, although it is grammatical. We will see that I-focus elements may fill the preverbal position in Old French as well. This evidence goes against the hypothesis that Old French is a topic-initial language.

Finally, if the Vorfeld in Germanic V2 languages is the host of various types of informational elements, including those pertaining to the I-Focus of the clause, but the preverbal field in Old French is a Topic position (holding I-Topics and scene-setting elements), we would expect the statistical distribution of preverbal elements to differ when the two are compared. The comparisons discussed in Section 7 do not bear out this prediction.

Our conclusion will be that, from the informational point of view, Old French does not appear to differ markedly from standard Germanic V2 languages.

5. Verb-initial (V1) Clauses

We begin with V1 clauses. If the Old French postverbal field is interpreted as the I-focus of the clause, V1 clauses should be thetic (all-focus). In other words, if subjects must move to the preverbal position in order to avoid being interpreted as part of the I-focus, the postverbal subjects of V1 clauses should be construed as belonging to the I-focus portion of the clause. To verify this prediction, we first considered sentences other than those where the verb introduces direct discourse (section 5.1), and then turned our attention to verbs of saying (section 5.2).

5.1 Verbs other than those introducing direct discourse

We extracted the strict V1 clauses of the corpus (i.e., those not introduced by a coordinator) having a full subject and a verb distinct from those introducing direct discourse. Taking the context into account, we hand-coded the subjects as being I-topic, I-focus, or UnclearFootnote 5. Table 1 shows that, while there is a dominance of I-focus subjects, over a third of the postverbal subjects were coded as I-topic. Examples (6) and (7) illustrate postverbal subjects coded as I-topics.

(6) (The Philistines ask a question of the Jews and the answer doesn't please them.)

Curecerent s’ en les princes des Philistiens

got-angry refl gen the princes of.the Philistines

‘The princes of the Philistians got angry at this.’ (1170; QLR, 1–2; 1332)

(7) (Brendan is the main protagonist. He and his followers land, and hope to relax after a long journey. However, a tempest approaches.)

Cunuit Brandans a l’ air pluius/Que li tens ert mult annüus.

knew Brendan from the air rainy/that the weather was very worrisome

‘Brendan knew from the wet wind that the weather was worrisome’ (1120; Brendan, 56; 675)

Table 1: Informational role of postverbal subjects in V1 declaratives.

The results in Table 1 counter Rinke and Meisel's claim that, in Old French, postverbal subjects are internal to the verb phrase and interpreted as part of the I-focus. Rather, they confirm Rouveret's (Reference Rouveret2004: 196) comment that “It does not seem that the postverbal position in [Old French] V1 sentences is pragmatically specialized.”

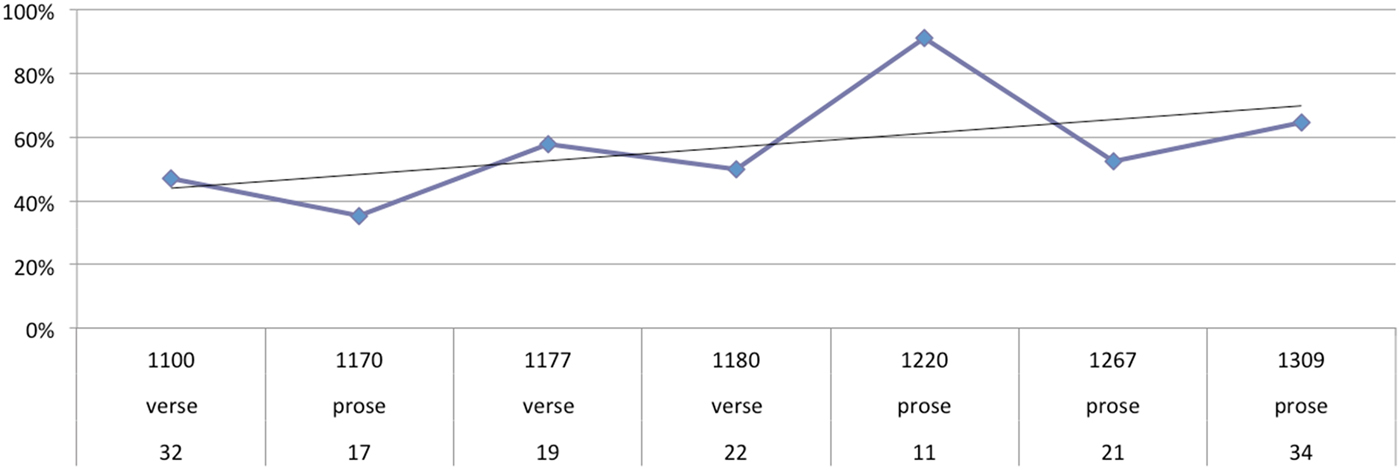

Figure 1 illustrates the evolution of V1 declaratives over time. In Roland (1100), the vast majority of postverbal subjects were coded as being I-focus, whereas in Brendan (1120) and the QLR (1170), they were more often I-topics. The V1 construction dropped out of the language at the beginning of the 13th century, when the language became more strictly V2. This is why there are few examples of V1 declaratives after 1170; three texts dated between 1205 and 1267 contain no V1 declaratives. After 1267, V1 declaratives reappear. They contain no clear I-topic subject, but there are only seven examples. Thus, at least for the period before the 13th century, when V1 declaratives were productively used, I-topic subjects did not need to move to the left of the verb; they could remain postverbal in V1 declaratives.

Figure 1: V1 declaratives–Informational nature of subjects: Number of postverbal subjects that are I-topic, I-focus or Unclear. The numbers at the bottom indicate the total number of relevant examples.

The postverbal position of I-topic subjects in V1 sentences is not compatible with the hypothesis that Old French sentences are dominated by TP, with the verb under T and the postverbal field expressing the comment and containing the I-focus portion of the clause. The facts are explained if we assume, following Labelle and Hirschbühler (Reference Labelle, Hirschbuhler, Batllori, Hernanz, Picallo and Roca2005), that, in V1 constructions, the emphasis is on the verb, which moves to a discourse-related position within the left periphery. Labelle and Hirschbühler propose that the verb in V1 clauses first moves to Fin, then, in a second step, to a higher discourse-related head, which they label ‘Z’, and which could correspond to focus in the articulated structure of the left periphery proposed by Benincà and Poletto (Reference Benincà, Poletto and Rizzi2004), shown in (8).

(8) [ HT [ Scene setting [ Force [ topic [ focus [ WH [ Fin ]]]]]]]

Under Labelle and Hirschbühler's analysis, postverbal subjects could occupy either [Spec,vP] or [Spec,TP], and one could explore the hypothesis that I-focus subjects occupy [Spec,vP] while I-topic subjects occupy [Spec,TP], as proposed by Rinke and Meisel.

(9) a. [FocP Cunuit [FinP cunuit [TP cunuit [vP Brandans cunuit …] (=(6))

b. [FocP Cunuit [FinP cunuit [TP Brandans cunuit [vP Brandans cunuit …]

But to account for the fact that postverbal subjects could be I-topics, we need to assume a derivation of V1 clauses that involves the left periphery in a manner similar to what happens in V2 sentences. Such a structure is compatible with the V2 nature of Old French if we assume, with Ledgeway (Reference Ledgeway2008: 439), that V2 is not a surface linear constraint, but a syntactic requirement that the verb raise to the C-domain in general, though not necessarily, with fronting of a pragmatically salient constituent to its left.

5.2 Verbs introducing direct discourse

Let us now turn to verbs introducing direct discourse. As schematized in (10)–(12), with these verbs, V1 declaratives (10) alternate with V2 declaratives, some of the SV(X) type (11), and some of the XVS type (12), where the preverbal element is either a cataphoric object or an adverb.

(10) Dit Roland: “ … ” = VS

‘Says Roland: ….’

(11) Roland dit: “ … ” = SV

‘Roland says: ….’

(12) a. Ço dit Roland: “ … ” = Cataphoric object VS

‘This says Roland: ….’

b. Donc dit Roland: “ … ” = Adverb VS

‘Thus says Roland: ….’

We did not consider verbs of saying in parentheticals, nor cases where the verb of saying follows the direct discourse, because there is no word order variation in these cases: the subject is always postverbal.

As far as we could see, the informational role of the subject is the same in examples (10)–(12). If this is correct, the preverbal or postverbal position of the subject is not dictated exclusively by its informational role. The following analysis attempts to verify this by focusing on the following question: with the disappearance of VS declaratives at the beginning of the 13th century, which construction replaces VS declaratives? If the postverbal position of the subject in VS declaratives was dictated by Information Structure, VS sentences are expected to be replaced by XVS sentences, to keep the subject postverbal. However, Figure 2 shows that, when the rate of VS sentences dropped dramatically (between 1177 and 1225), the proportion of SV(X) sentences increased, but not that of XVS sentences.

Figure 2: Verbs introducing direct discourse: Rates of SVX sentences as compared to VS and XVS sentences. The numbers at the bottom correspond to the number of relevant examples.

The fact that SV sentences are replacing VS sentences casts serious doubts on the idea that the subject's informational role dictates its position. Moreover, there is no support for the hypothesis that I-topic subjects could not remain postverbal. The vast majority of the subjects are definite and discourse-old both in SV and in VS sentences. In 99% (573/580) of the examples containing a verb of saying, the subject is definite.Footnote 6 As definite subjects correspond to known information, they tend to represent the I-topic, particularly in the discourse context of verbs of saying.

Figure 2 suggests that VS order in declaratives resulted from a desire to place the verb first, and not from the need to leave the subject in a postverbal I-focus position. When speakers started to avoid placing emphasis on the verb in declaratives, a V2 construction was used instead, with the verb remaining under Fin and some constituent filling [Spec,FinP]. The fact that I-topic subjects were largely preferred over either objects or adverbs to fill the preverbal position is coherent with the distribution of preverbal elements in V2 sentences (see section 7, table 4).

To summarize this section, the hypothesis that subjects need to move to the preverbal position to avoid being interpreted as I-focus is refuted. Postverbal subjects in V1 clauses are often the I-topic of the clause. It could very well be that subjects move to [Spec,TP] in order to be interpreted as I-topics. However, we must conclude that the Old French clause structure projects higher up than [Spec,TP] and that the Old French verb moves to the left periphery in V1 main clauses. This movement to the left periphery is in line with the standard V2 analysis of Old French.

6. V2 Clauses

Let us now turn to V2 clauses. Two questions are addressed in this section: First, what is the informational role of the postverbal subjects in V2 clauses? Second, what is the informational role of the preverbal constituents?

6.1 Subjects

Because definite subjects tend to be I-topics, whereas indefinite subjects make bad I-topics and are often found in thetic sentences, we asked ourselves whether, in V2 sentences, there is a marked tendency to find definite subjects preverbally and indefinite subjects postverbally. To answer this question, we automatically coded the nature of subjects in the 4397 non-coordinated V2 sentences. Subjects coded as “definite” include those introduced by a definite, possessive or demonstrative determiner, DPs headed by a demonstrative or other referential pronoun, and proper nouns; “indefinite” subjects include DPs headed by a partitive or indefinite determiner. Bare NPs and DPs headed by a quantifier (like tous ‘all’, plusieurs ‘many’), which could be definite or indefinite, were counted separately. Figures 3a and 3b show that subjects are overwhelmingly definite, both preverbally and postverbally. Given that definite subjects mostly introduce known or retrievable information, and rarely new information, the large number of postverbal definite subjects casts serious doubt on the idea that postverbal subjects could not be I-topics.

Figure 3a: Preverbal subject types: Rates of subject types in preverbal position.

Figure 3b: Postverbal subject types: Rates of subject types in postverbal position.

Preverbal definite subjects are expected to be I-topics. Because this would be compatible with Rinke and Meisel's claims, we did not study them further, but rather focused our attention on the 192 indefinite subjects. We found a small tendency to place indefinite subjects postverbally, but clearly no exclusion of indefinite subjects from the preverbal position: 44.7% of indefinite subjects are preverbal in verse texts (12th century) and 43% in prose texts (1170 and 13th century). Examples (13) and (14) show that these indefinite preverbal subjects may be the I-focus of the clause; the contexts should make clear that the indefinite subjects carry brand new information. We conclude from this that the preverbal position may host informationally new, I-focus, elements.Footnote 7, Footnote 8

(13) (Eliduc is looking for a burial place for his love. He remembers that near his domain there is a large forest. A holy hermit lived there, and there was a chapel there. He had talked to him many times. He will bring his love to him, for him to bury her in his chapel.)

Un seinz hermites i maneit et une chapele i aveit

A holy hermit loc lived and a chapel loc had

‘A holy hermit lived there and there was a chapel there.’

(1180; Marie de France, Eliduc 182;3715)

(14) (While Eliduc's wife is crying next to a dead girl, a weasel comes running out from under the altar and passes over the corpse. The valet kills it and throws its corpse in a corner.)

Une musteile vint curant, desuz l’ auter esteit eissue

A weasel came running, under the altar was come.out

‘A weasel came running out from under the altar.’

(1180; Marie de France, Eliduc 187;3815)

Considering only texts containing more than ten indefinite subjects, we observe a small increase in the tendency to place indefinite subjects in postverbal position (Figure 4), but the percentage of preverbal indefinite subjects at the end of the period is still 35%. Thus, there does not seem to be any constraint against preverbal I-focus subjects during the period under investigation.

Figure 4: Postverbal indefinite subjects over total indefinite subjects (in text with more than 10 indefinite subjects): Rates of postverbal indefinite subjects. The numbers at the bottom correspond to the total number of relevant examples.

To summarize this subsection, the distribution of definite vs indefinite subjects in V2 clauses does not support the hypothesis that subjects move to the preverbal position to avoid being interpreted as I-focus. This conclusion will be supported in Section 6.2.3, which presents a quantitative analysis of the informational role of postverbal subjects in sentences containing a preverbal adverbial.

6.2 Preverbal nonsubject constituents

Rinke and Meisel (Reference Rinke, Meisel, Kaiser and Remberger2009) claim that, while in German the preverbal constituent may be a topic, an I-focus, or an element that is neither topic nor focus, the preverbal constituent in Old French is always a topic (an I-topic, or an adverb with topical properties). In this section, we consider XVS sentences with the aim of determining whether the preverbal position is a topic position, and whether postverbal subjects are interpreted as being part of the I-focus portion of the clause.

Since clause-initial contrastive elements could result from movement to a dedicated contrastive focus projection within the left periphery (Rizzi's Reference Rizzi and Haegeman1997 FocP), we will set aside examples like (15) containing an overtly contrastive preverbal constituent.

(15) Meïsmes a l' empereour sont les lermes venues aus yex,

even to the emperor are the tears come-ptcp to-the eyes

‘Even to the emperor, the tears came to the eyes.’ (1267; Cassidorus, 664;4447)

6.2.1 Preverbal objects.

The OVS word order in 13th century texts has been studied by Rickard (Reference Rickard1962), who shows that, in addition to establishing a link with the previous discourse, the preverbal position may also be a prominence position serving to convey a brand-new and affectively important idea. Marchello-Nizia (Reference Marchello-Nizia1995, Reference Marchello-Nizia1999), who studied the role of preverbal direct objects in two texts, Roland (1100) and La Queste del Saint Graal (1225), noticed a change in the informational role of preverbal objects. In Roland, there is no restriction on the informational role of preverbal objects, but they tend to be, in her terms, more often rhematic (I-focus) than thematic (I-topic) (Marchello-Nizia Reference Marchello-Nizia1995: 99–100). By contrast, the OV(S) order is more restricted in the Queste, where, according to Marchello-Nizia, it serves mainly to thematize the object. When the object is rhematic, the OVS order is marked and is found mainly in idioms of type mander saluz ‘send greetings’, as in (16), or when O is either strongly focused or cataphorically linked to the discourse.Footnote 9

(16) Saluz vos mande li bons chevaliers

Greetings you send the good knight

‘The good knight sends you his greetings’ (Queste, p. 30, cited in Marchello-Nizia Reference Marchello-Nizia1999: 44)

Our corpus study confirms the change in the informational role of preverbal objects. Taking context into account, we coded all preverbal objects in V2 sentences as I-topic, I-focus, or unclear. As shown in Figure 5, a preverbal object tended to be the I-focus of the clause before 1205, but the I-topic of the clause, after 1225.

Figure 5: Informational status of preverbal objects: Rates of preverbal objects that are I-focus, I-topic, or Unclear. The numbers at the bottom correspond to the total number of relevant examples.

The examples in (17)–(20) contain preverbal objects analyzed as part of the I-focus:

(17) (Marsile comes through a valley with the great army he had assembled)

.XX. escheles ad li reis anumbrees.

twenty columns has the king counted

‘The King has organized them in twenty divisions.’Footnote 10 (1100; Roland, 112;1459)

(18) (After the storm, a large quantity of birds assembled on the pine tree, they all sang with perfect harmony.)

et divers chanz chantoit chascuns;

and various songs sang each.one’

‘and they all sang a different song’ (1177; Yvain, 15;453)

(19) (Lunete asks the lady to swear that she will help the knight)

La main destre leva adonques la dame,

The hand right raised then the lady

‘Then the lady raised the right hand’ (1177; Yvain, 202;7065)

(20) (While the king fortified Sayete, merchants arrived and told us that the king of the Tartars had taken the city of Baudas.)

La maniere comment il pristrent la cité de Baudas et le calife nous conterent

The manner how they took.pl the city of Baudas and the caliph us told

les marcheans;

the merchants

‘The merchants told us how they took the city of Baudas and the caliph’

(1309; de Joinville 289; 3370.Footnote 11)

It can be seen that the postverbal definite subjects are not part of the comment or I-focus of the clause, but constitute the old information of the clause and its I-topic (the entity under which the comment must be stored in the common ground).

A change in the informational ordering of constituents seems to have happened at the beginning of the 13th century. This change led to a tendency to leave I-focus objects in postverbal position. This trend could suggest that the language changed from having a preverbal position unrestricted with respect to information role, towards a situation where the preverbal position tends to be restricted to I-topics. However, since the OVS order with a preverbal I-focus object counts for twenty to forty percent of preverbal objects until the end of the period, one cannot say that the language becomes a topic-initial language at the beginning of the 13th century. The detailed analysis of the OV order carried out by de Andrade (this issue) confirms this finding. De Andrade shows, among other things, that it is only in the 15th century (that is, in Middle French) that informational focus objects become rare in preverbal position.Footnote 12 We will come back to the change that affected preverbal objects in section 7 below.

We conclude that, in Old French, the preverbal position may be occupied by an I-focus, in which case a postverbal subject may be the I-topic.

6.2.2 Preverbal predicates and quantifiers

In Old French, the preverbal position may be filled by constituents that are not good candidates for topic-hood. These include quantifiers, non-finite verbs, adjectives and other predicates.

In (21), the preverbal predicate is known information. It establishes a link with the previous chapter and introduces a contrast with the second clause. It is neither the I-topic nor the I-focus of the discourse.

(21) (Beginning of the section on rebellion, after a section on the sin of grumbling [murmuring against an authority].)

Male chose est murmure, mes trop vaut pis rebellion.

bad thing is grumble but too.much be.worth worse rebellion

‘Grumbling is a bad thing, but rebellion is much worse.’ (1279; Somme, 1,64; 1758)

However, in general, preverbal predicates and quantifiers are interpreted as part of the I-focus. When that is the case, subject may appear postverbally and be construed as I-topics. Examples (22)–(24) illustrate this situation.

(22) (Lanval leaves his hosts, rides towards the town. He often looks behind him.)

Mut est Lanval en grant esfrei!

much is Lanval in great fear

‘Lanval is greatly afraid.’ (1180; Marie de France, Lanval, 196; 78.1592)

(23) (Count Roland says to Marsile “…today you'll learn my sword's name”. He goes to strike him.)

Trenchet li ad li quens le destre poign

cut-ptcp him has the count the right hand

‘The count has cut his right hand.’ (1100; Roland, 142; 1926)

(24) (The girl, hiding in a shelter, disinherited and disconsolate, becomes full of joy upon hearing that the Lion Knight is coming (to defend her). She thinks that, now, her sister will give her part of her inheritance.)

Malade ot geü longuemant la pucele

sick has laid a.long.time the girl

‘The girl had been sick for a long time.’ (1177; Yvain, 177; 6235)

Preverbal predicates and quantifiers were always rare in preverbal position compared to adverbials and PPs. Table 2 shows that their percentage is higher in verse texts (12th century) than in prose texts (mainly 13th century). It could be that versification constraints favored the use of an atypical word order. It might also be that after the 12th century, speakers were less likely to place I-focus elements in preverbal position, echoing what was found with objects.

Table 2: Distribution of adjectives, predicative NPs and non finite verbs in preverbal position.

6.2.3 Adverbials

We coded the informational status of postverbal subjects in V2 sentences introduced by an adverbial, or a scene-setting temporal DP like le lendemain ‘the next day’. There were about 9% of cases that we were unable to code (86 cases out of 975); these were removed from the analysis. The majority of the postverbal subjects (71%) were coded as I-topic. Only 29% of the postverbal subjects were coded as new information, that is, as I-focus. Figure 6, illustrating only the texts for which we had at least nine relevant examples, demonstrates that no observable change is apparent within the period considered.

Figure 6: Information function of postverbal subjets in Adv-V-S clauses: Percentage of postverbal subjects that are coded as I-focus or I-topic in texts containing more than nine relevant examples.

In the majority of cases, the preverbal adverb is a short temporal adverbial like lors, puis, après, donc, adont, or the particle si. In these cases, the preverbal element is neither a topic nor an I-focus, but a cohesive element, linking to the previous discourse. When such an element is preverbal, the I-topic appears postverbally. The postverbal placement of I-topics is expected in a V2 system, and it is observed in German.

(25) (Ydoines asks Helcanor if he prayed God to give him his hands back; Helcanor answers “Yes I did.”)

Dont sot Ydoines vraiement que Diex l’ amoit,

Then knew Ydoine truly that God her loved

‘Then Ydoine truly knew that God loved her.’ (1267; Cassidorus, 351; 3031)

(26) (Perceval wants to leave immediately, but his aunt refuses to give him leave, saying that he should stay overnight and leave after hearing mass in the morning. Perceval stays. The servants install the table. Perceval and his aunt eat the meal prepared for them.)

Si demora laienz Perceval avec s’ antain.

thus stayed therein Perceval with his aunt

‘Thus, Perceval stayed there with his aunt.’ (1225; Queste, 107; 2806)

A second category of preverbial adverbials includes locative or temporal scene-setting elements. Here again, the postverbal subject is usually interpreted as the I-topic of the clause. The examples in (27) and (28) illustrate this type of situation. These examples show that in Old French, scene-setting adverbs do not necessarily occupy the preverbal position when no I-topic is available to fill it. On the contrary, Old French appears to function like German, where, according to Speyer (Reference Speyer, Benz and Kühnlein2008), when a clause contains both a scene-setting element and an I-topic, the scene-setting element has priority for filling the Vorfeld.

(27) (Cassidorus takes his spear and runs towards Lapsus to fight.)

La fist Cassidorus plus d’ armes

There made Cassidorus more (feats) of arms

que onques Achilles ne fist devant Troies.

than ever Achilles neg made in.front.of Troy

‘There, Cassidorus made more feats of arms than Achilles ever made in front of Troy.’

(1267; Cassidorus, 26; 627)

(28) (During Lent, the king had his boats prepared to go back to France. On the eve of Saint Mark's day, after Easter, the king and the queen prayed on their boats; they set sail with fair winds.)

Le jour de la saint Marc me dit le roy que a celi jour il avoit esté né;

The day of the Saint Marc me told the king that at that day he had been born

‘On Saint Marc's day, the king told me that he was born that day;’

(1309; de Joinville, 305; 3574)

Our results can be summarized as follows. In the preverbal position of V2 sentences, we observed not only elements treated as topics by Rinke and Meisel (I-topics and scene-setting adverbials), but also elements that were the I-focus of the clause as well as adverbs that are neither topics nor focus. In postverbal position, we counted a large number of definite subjects interpreted as the I-topic of their clause. We conclude that Old French was not a topic-initial language and that subjects could remain postverbal without being interpreted as part of the I-focus. Therefore, from the informational point of view, Old French resembles German. The standard analysis whereby the verb moves to the left periphery in main clauses accounts adequately, not only for the V2 examples, but also for the V1 examples.

7. Comparison with Germanic Languages

In this section, we compare the distribution of preverbal constituents in Old French and in Germanic languages. If the information role of the preverbal constituent in Old French is similar to what is observed in Germanic V2 languages, we expect the distributions to be similar. If, however, Old French is not V2 but is a topic-initial language, we expect this fact to be reflected in the distribution. We base our comparison on the study by Bohnacker and Rosén (Reference Bohnacker, Rosén, Anderssen and Westergaard2007).

Bohnacker and Rosén (Reference Bohnacker, Rosén, Anderssen and Westergaard2007) compare the prefields in German and Swedish, and they arrive at the figures in Table 3 (which combines their Tables 1–3, pages 34 and 36). Table 3 can be compared with our results for Old French in Table 4. The percentages of the various types of preverbal constituents are of the same order of magnitude in Old French and in the two Germanic languages. This comparison reinforces our claim that during the 12th and 13th centuries, Old French was not a topic-initial language, but, rather, a V2 language similar in the relevant respects to German and Swedish.

Table 3: Constituents in the prefield in German and Swedish (from Bohnacker and Rosén Reference Bohnacker, Rosén, Anderssen and Westergaard2007).

Table 4: Constituents in the prefield in Old French.

Commenting on the figures in Table 3, Bohnacker and Rosén explain the difference in the percentages of fronted objects in German (about 7%) as compared to Swedish (about 3%) as follows: both Swedish and German tend to start declaratives with a subject coinciding with the theme and topic, and to place the theme before the rheme. However, Swedish has a stronger tendency to place the rheme after the verb, to start with a light element or one of low informational value (e.g., an expletive, det, så), and to use few fronted objects. Although the constructions with a heavy rhematic (i.e., I-focus) object found in German are considered grammatical in Swedish, they are dispreferred. Swedish typically fronts objects that are themes (i.e., I-topics).

Turning to Old French, Table 4 shows that the percentage of preverbal objects in verse texts (12th century) is similar to what is found in German, while the corresponding percentage in prose texts (mainly13th century) is similar to what is found in Swedish. If we add to this observation the decrease of I-focus preverbal objects in prose texts (section 6.2.1), the lower percentage of preverbal predicates and non-finite verbs in prose texts (section 6.2.2), and the small increase in the proportion of postverbal indefinite subjects (section 6.1), we are tempted to conclude (if the differences are not exclusively due to text genre) that the use of the prefield during the period considered evolved from one similar to that of contemporary German to one similar to that of contemporary Swedish. These changes might indicate a change towards a preference for keeping I-focus constituents within the VP. It is clear, nonetheless, that I-topics are not restricted to the preverbal position during the period considered, contrary to what was argued by Rinke and Meisel (Reference Rinke, Meisel, Kaiser and Remberger2009). Moreover, as German and Swedish are both V2 languages, the shift observed in Old French cannot be taken as an argument against the analysis of Old French as a V2 language.

8. Conclusion

We have argued that, from an information-structure viewpoint, Old French was essentially a V2 language of the Germanic type until the end of the 13th century. Just as in German, the preverbal position of an Old French sentence could be filled by an I-focus, by an I-topic, by a scene-setting topic, or by an adverb that was neither a topic nor part of the I-focus. Moreover, postverbal subjects were frequently interpreted as I-topics; therefore, subjects did not need to move to the preverbal position to avoid being interpreted as part of the I-focus. This is what is expected of a language in which the verb moves to a position within the left periphery (FinP or higher) with some constituent merged to its left in V2 sentences. If the verb occupies a position within the left periphery, postverbal subjects in SpecTP may be construed as I-topics.

Our research allowed us to advance in the description of the evolution of Old French, in that we noticed a slight change in the use of the left periphery. The 12th-century grammar is statistically closer to that of German, while the 13th-century grammar is similar to that of Swedish. This shift appears to reflect a change in progress towards a grammar where new information preferentially occurs in postverbal position. Specifically, noncontrastive elements carrying the I-focus of the clause are less frequently preverbal at the end of the period, compared to what was found at the beginning. If the differences are not exclusively due to text genre, they reflect one of the first steps towards the loss of the V2 grammar and the emergence of an SVO grammar, as argued by Marchello-Nizia (Reference Marchello-Nizia1995). It would be interesting to study Middle French V2 sentences to better understand this evolution.

List of Old French texts studied, by date