1 Introduction and results

Let f be a holomorphic function on the unit disk

![]() $\mathbb {D} = \{z \in \mathbb {C} : |z| < 1 \}$

, and let

$\mathbb {D} = \{z \in \mathbb {C} : |z| < 1 \}$

, and let

![]() $\mathbb {T} =\partial \mathbb {D}$

be the unit circle. In [Reference Pólya and Szegő21, p. 165, Problem 309], Pólya and Szegő observed that if

$\mathbb {T} =\partial \mathbb {D}$

be the unit circle. In [Reference Pólya and Szegő21, p. 165, Problem 309], Pólya and Szegő observed that if

![]() $\mathrm {L}_{\mathrm {e}}$

denotes the euclidean length of a curve, the function

$\mathrm {L}_{\mathrm {e}}$

denotes the euclidean length of a curve, the function

$$ \begin{align} r \mapsto \frac{\mathrm{L}_{\mathrm{e}} (f (r \mathbb{T}))}{ \mathrm{L}_{\mathrm{e}} (r \mathbb{T})}= \frac{1}{2 \pi} \int\limits_{0}^{2\pi} \left| f^{\prime}(r e^{it}) \right| dt \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} r \mapsto \frac{\mathrm{L}_{\mathrm{e}} (f (r \mathbb{T}))}{ \mathrm{L}_{\mathrm{e}} (r \mathbb{T})}= \frac{1}{2 \pi} \int\limits_{0}^{2\pi} \left| f^{\prime}(r e^{it}) \right| dt \end{align} $$

is increasing on the interval

![]() $(0,1)$

. Much more recently, it was proved by Aulaskari and Chen [Reference Aulaskari and Chen1] and Burckel et al. [Reference Burckel, Marshall, Minda, Poggi-Corradini and Ransford5] that if

$(0,1)$

. Much more recently, it was proved by Aulaskari and Chen [Reference Aulaskari and Chen1] and Burckel et al. [Reference Burckel, Marshall, Minda, Poggi-Corradini and Ransford5] that if

![]() $\mathrm {A}_{\mathrm {e}}$

denotes the euclidean area of a domain, the function

$\mathrm {A}_{\mathrm {e}}$

denotes the euclidean area of a domain, the function

$$ \begin{align} r \mapsto \frac{\mathrm{A}_{\mathrm{e}} (f(r \mathbb{D}))}{\mathrm{A}_{\mathrm{e}} (r\mathbb{D})}=\frac{1}{\pi r^2} \mathrm{A}_{\mathrm{e}} f(r \mathbb{D}) \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} r \mapsto \frac{\mathrm{A}_{\mathrm{e}} (f(r \mathbb{D}))}{\mathrm{A}_{\mathrm{e}} (r\mathbb{D})}=\frac{1}{\pi r^2} \mathrm{A}_{\mathrm{e}} f(r \mathbb{D}) \end{align} $$

is also monotonically increasing. These investigations have since then led to a series of monotonicity results comparing other euclidean geometric and euclidean potential theoretic quantities of the image

![]() $f(r \mathbb {D})$

with those corresponding to

$f(r \mathbb {D})$

with those corresponding to

![]() $r\mathbb {D}$

. This way, quantitative bounds on the growth behavior of the image

$r\mathbb {D}$

. This way, quantitative bounds on the growth behavior of the image

![]() $f(r \mathbb {D})$

have been established, leading to several distortion theorems. Examples of such euclidean geometric and potential theoretic quantities are the diameter, nth diameter, logarithmic capacity, inner radius, and total curvature (see [Reference Betsakos2, Reference Betsakos3, Reference Burckel, Marshall, Minda, Poggi-Corradini and Ransford5, Reference Kourou11]).

$f(r \mathbb {D})$

have been established, leading to several distortion theorems. Examples of such euclidean geometric and potential theoretic quantities are the diameter, nth diameter, logarithmic capacity, inner radius, and total curvature (see [Reference Betsakos2, Reference Betsakos3, Reference Burckel, Marshall, Minda, Poggi-Corradini and Ransford5, Reference Kourou11]).

Even more recently, starting with the work of Betsakos [Reference Betsakos4], many of these euclidean geometric Schwarz-type lemmas have been carried over to the hyperbolic setting. For instance, in [Reference Betsakos4], results are proved concerning the hyperbolic area radius of

![]() $f(r \mathbb {D})$

and its hyperbolic capacity. Furthermore, the notion of hyperbolic convexity has led to corresponding monotonicity theorems regarding total hyperbolic curvature, hyperbolic length, and area (see [Reference Kourou12]).

$f(r \mathbb {D})$

and its hyperbolic capacity. Furthermore, the notion of hyperbolic convexity has led to corresponding monotonicity theorems regarding total hyperbolic curvature, hyperbolic length, and area (see [Reference Kourou12]).

The purpose of the present work is to establish sharp estimates and monotonicity results for geometric quantities such as spherical length, spherical area, and total spherical curvature for spherically convex functions on the unit disk. Spherically convex functions have been investigated by many authors, including Wirths, Kühnau, Ma, Minda, Mejía, Pommerenke, and others (see [Reference Kühnau13–Reference Mejía and Pommerenke16, Reference Wirths25] and the references therein). In studying spherical analogs of the aforementioned euclidean and hyperbolic monotonicity results and geometric Schwarz’s lemmas, one faces a number of difficulties caused by effects of positive curvature as well as several phenomena which are not present at all in the euclidean and hyperbolic situation, and hence a different approach and different tools are required. This paper addresses these issues.

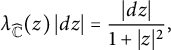

In order to state our results, we first need to recall some basic concepts from spherical geometry. For more details, the reader might consult Section 2 and also [Reference Minda17, Reference Minda18], for instance. We equip the Riemann sphere

![]() $\widehat {\mathbb {C}}=\mathbb {C} \cup \{\infty \}$

with the spherical metric

$\widehat {\mathbb {C}}=\mathbb {C} \cup \{\infty \}$

with the spherical metric

$$ \begin{align*}\lambda_{\widehat{\mathbb{C}}}(z) \, |dz|=\frac{|dz|}{1+|z|^2} ,\end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*}\lambda_{\widehat{\mathbb{C}}}(z) \, |dz|=\frac{|dz|}{1+|z|^2} ,\end{align*} $$

the canonical conformal Riemannian metric on

![]() $\widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

with constant Gaussian curvature

$\widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

with constant Gaussian curvature

![]() $+4$

. For two points

$+4$

. For two points

![]() $a,b \in \widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

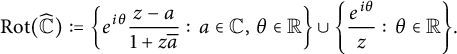

which are not antipodal, the unique spherical geodesic joining a and b is the smaller arc of the great circle through a and b. The meromorphic spherical isometries form the group of rotations of

$a,b \in \widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

which are not antipodal, the unique spherical geodesic joining a and b is the smaller arc of the great circle through a and b. The meromorphic spherical isometries form the group of rotations of

![]() $\widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

which is explicitly given by

$\widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

which is explicitly given by

$$ \begin{align*}\operatorname{\mathrm{Rot}}(\widehat{\mathbb{C}}) := \left\{ e^{ i \theta} \frac{z-a }{1+z \overline{a}} : \, a \in \mathbb{C}, \, \theta \in \mathbb{R} \right\} \cup \left\{ \frac{e^{i \theta}}{z} : \, \theta \in \mathbb{R} \right\}\!.\end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*}\operatorname{\mathrm{Rot}}(\widehat{\mathbb{C}}) := \left\{ e^{ i \theta} \frac{z-a }{1+z \overline{a}} : \, a \in \mathbb{C}, \, \theta \in \mathbb{R} \right\} \cup \left\{ \frac{e^{i \theta}}{z} : \, \theta \in \mathbb{R} \right\}\!.\end{align*} $$

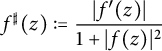

For a meromorphic function

![]() $f : \mathbb {D} \to \widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

, the spherical derivative

$f : \mathbb {D} \to \widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

, the spherical derivative

$$ \begin{align*}f^{\sharp}(z):=\frac{|f'(z)|}{1+|f(z)|^2}\end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*}f^{\sharp}(z):=\frac{|f'(z)|}{1+|f(z)|^2}\end{align*} $$

is invariant under postcomposition with any

![]() $T \in \operatorname {\mathrm {Rot}}(\widehat {\mathbb {C}})$

, that is,

$T \in \operatorname {\mathrm {Rot}}(\widehat {\mathbb {C}})$

, that is,

![]() $(T \circ f)^{\sharp }(z)=f^{\sharp }(z)$

.

$(T \circ f)^{\sharp }(z)=f^{\sharp }(z)$

.

A domain

![]() $\Omega $

on the Riemann sphere

$\Omega $

on the Riemann sphere

![]() $\widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

is called spherically convex if for any two points

$\widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

is called spherically convex if for any two points

![]() $a,b \in \Omega $

that are not antipodal, the spherical geodesic joining a and b lies entirely in

$a,b \in \Omega $

that are not antipodal, the spherical geodesic joining a and b lies entirely in

![]() $\Omega $

. A meromorphic univalent map

$\Omega $

. A meromorphic univalent map

![]() $f: \mathbb {D} \to \widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

is called spherically convex if

$f: \mathbb {D} \to \widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

is called spherically convex if

![]() $f(\mathbb {D})$

is a spherically convex domain in

$f(\mathbb {D})$

is a spherically convex domain in

![]() $\widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

.

$\widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

.

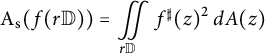

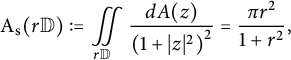

Our first result provides a sharp upper bound for the spherical area

$$ \begin{align*}\mathrm{A}_{\mathrm{s}} (f(r \mathbb{D}))=\iint \limits_{r \mathbb{D}} f^{\sharp}(z)^2 \, dA(z)\end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*}\mathrm{A}_{\mathrm{s}} (f(r \mathbb{D}))=\iint \limits_{r \mathbb{D}} f^{\sharp}(z)^2 \, dA(z)\end{align*} $$

of the image

![]() $f(r \mathbb {D})$

of any spherically convex function

$f(r \mathbb {D})$

of any spherically convex function

![]() $f: \mathbb {D} \to \widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

in terms of

$f: \mathbb {D} \to \widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

in terms of

$$ \begin{align*}\mathrm{A}_{\mathrm{s}} (r\mathbb{D}):=\iint \limits_{r \mathbb{D}} \frac{dA(z)}{\left(1+|z|^2\right)^2}=\frac{\pi r^2}{1+r^2} ,\end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*}\mathrm{A}_{\mathrm{s}} (r\mathbb{D}):=\iint \limits_{r \mathbb{D}} \frac{dA(z)}{\left(1+|z|^2\right)^2}=\frac{\pi r^2}{1+r^2} ,\end{align*} $$

the spherical area of the disk

![]() $r \mathbb {D}$

.

$r \mathbb {D}$

.

Theorem 1.1 (Area Schwarz’s lemma for spherically convex functions)

Let

![]() $f : \mathbb {D} \to \widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

be spherically convex. Then

$f : \mathbb {D} \to \widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

be spherically convex. Then

Moreover, equality holds for some

![]() $0<r<1$

if and only if f is a spherical isometry.

$0<r<1$

if and only if f is a spherical isometry.

Theorem 1.1 raises the problem whether there exists a corresponding lower bound for the ratio

$$ \begin{align} \mathcal{A}_{\mathrm{s}}(r) : = \frac{\mathrm{A}_{\mathrm{s}} (f(r \mathbb{D}))}{ \mathrm{A}_{\mathrm{s}} (r \mathbb{D})}, \quad r \in (0,1) . \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \mathcal{A}_{\mathrm{s}}(r) : = \frac{\mathrm{A}_{\mathrm{s}} (f(r \mathbb{D}))}{ \mathrm{A}_{\mathrm{s}} (r \mathbb{D})}, \quad r \in (0,1) . \end{align} $$

Note that (1.3) is the spherical analog of the euclidean quantity (1.2). Since

a lower bound for

![]() $\mathcal {A}_{\mathrm {s}}(r)$

would follow, provided one could prove that

$\mathcal {A}_{\mathrm {s}}(r)$

would follow, provided one could prove that

![]() $\mathcal {A}_{\mathrm {s}}(r)$

is increasing as a function of r.

$\mathcal {A}_{\mathrm {s}}(r)$

is increasing as a function of r.

Theorem 1.2 Let

![]() $f : \mathbb {D} \to \widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

be spherically convex. Then

$f : \mathbb {D} \to \widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

be spherically convex. Then

![]() $\mathcal {A}_{\mathrm {s}}(r)$

is a strictly increasing function of

$\mathcal {A}_{\mathrm {s}}(r)$

is a strictly increasing function of

![]() $r \in (0,1)$

, unless f is a spherical isometry in which case

$r \in (0,1)$

, unless f is a spherical isometry in which case

![]() $\mathcal {A}_{\mathrm {s}}(r) \equiv 1$

.

$\mathcal {A}_{\mathrm {s}}(r) \equiv 1$

.

Theorem 1.2 is a spherical analog of the previously known monotonicity results for euclidean and hyperbolic area [Reference Aulaskari and Chen1, Reference Burckel, Marshall, Minda, Poggi-Corradini and Ransford5, Reference Kourou12] mentioned at the beginning.

Corollary 1.1 Let

![]() $f : \mathbb {D} \to \widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

be a spherically convex function. Then

$f : \mathbb {D} \to \widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

be a spherically convex function. Then

Moreover, equality holds in (1.4) for some

![]() $0<r<1$

if and only if

$0<r<1$

if and only if

![]() $f $

is a spherical isometry.

$f $

is a spherical isometry.

Remark 1.1 (Theorem 1.2 vs. Theorem 1.1)

Clearly,

![]() $\mathrm {A}_{\mathrm {s}} (f(r \mathbb {D})) \le \pi /2$

for any spherically convex function

$\mathrm {A}_{\mathrm {s}} (f(r \mathbb {D})) \le \pi /2$

for any spherically convex function

![]() $f: \mathbb {D} \to \widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

, so Theorem 1.2 easily implies

$f: \mathbb {D} \to \widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

, so Theorem 1.2 easily implies

$$ \begin{align*}\frac{\mathrm{A}_{\mathrm{s}} (f(r \mathbb{D}))}{\mathrm{A}_{\mathrm{s}} (r\mathbb{D})}=\mathcal{A}_{\mathrm{s}}(r) \le \limsup \limits_{\rho \to 1-} \mathcal{A}_{\mathrm{s}}(\rho) \le \lim \limits_{\rho \to 1-} \frac{\pi/2}{\mathrm{A}_{\mathrm{s}} (\rho \mathbb{D})}=\lim \limits_{\rho \to 1-} \frac{1+\rho^2}{2 \rho^2}=1,\end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*}\frac{\mathrm{A}_{\mathrm{s}} (f(r \mathbb{D}))}{\mathrm{A}_{\mathrm{s}} (r\mathbb{D})}=\mathcal{A}_{\mathrm{s}}(r) \le \limsup \limits_{\rho \to 1-} \mathcal{A}_{\mathrm{s}}(\rho) \le \lim \limits_{\rho \to 1-} \frac{\pi/2}{\mathrm{A}_{\mathrm{s}} (\rho \mathbb{D})}=\lim \limits_{\rho \to 1-} \frac{1+\rho^2}{2 \rho^2}=1,\end{align*} $$

for every

![]() $0<r<1$

. In this sense, Theorem 1.1 appears as an easy corollary of Theorem 1.2. However, the proof of Theorem 1.2 we give below depends in an essential way on Theorem 1.1, so the apparently stronger statement of Theorem 1.2 is in fact equivalent to Theorem 1.1.

$0<r<1$

. In this sense, Theorem 1.1 appears as an easy corollary of Theorem 1.2. However, the proof of Theorem 1.2 we give below depends in an essential way on Theorem 1.1, so the apparently stronger statement of Theorem 1.2 is in fact equivalent to Theorem 1.1.

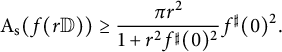

In passing, we note that the proof of Theorem 1.2 leads to another sharp lower bound for the spherical area

![]() $\mathrm {A}_{\mathrm {s}} (f(r \mathbb {D}))$

, which is more precise than the one provided by the sharp inequality (1.4), but geometrically less pleasing.

$\mathrm {A}_{\mathrm {s}} (f(r \mathbb {D}))$

, which is more precise than the one provided by the sharp inequality (1.4), but geometrically less pleasing.

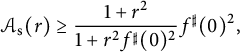

Corollary 1.2 Let

![]() $f : \mathbb {D} \to \widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

be a spherically convex function. Then

$f : \mathbb {D} \to \widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

be a spherically convex function. Then

$$ \begin{align*}\mathrm{A}_{\mathrm{s}} (f(r \mathbb{D})) \geq\frac{\pi r^2}{1+r^2 f^{\sharp}(0)^2} f^{\sharp}(0)^2 \quad \text{ for every } 0<r<1 .\end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*}\mathrm{A}_{\mathrm{s}} (f(r \mathbb{D})) \geq\frac{\pi r^2}{1+r^2 f^{\sharp}(0)^2} f^{\sharp}(0)^2 \quad \text{ for every } 0<r<1 .\end{align*} $$

Moreover, equality holds for any

![]() $0<r<1$

if f has the form

$0<r<1$

if f has the form

![]() $f(z)=T (\eta z)$

with

$f(z)=T (\eta z)$

with

![]() $T \in \operatorname {\mathrm {Rot}}(\widehat {\mathbb {C}})$

and

$T \in \operatorname {\mathrm {Rot}}(\widehat {\mathbb {C}})$

and

![]() $0<|\eta |\le 1$

.

$0<|\eta |\le 1$

.

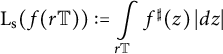

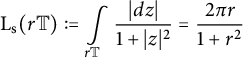

Our next results deal with the spherical length

$$ \begin{align*}\mathrm{L}_{\mathrm{s}} (f(r \mathbb{T})):= \int \limits_{r \mathbb{T}} f^{\sharp}(z) \, |dz|\end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*}\mathrm{L}_{\mathrm{s}} (f(r \mathbb{T})):= \int \limits_{r \mathbb{T}} f^{\sharp}(z) \, |dz|\end{align*} $$

of the image

![]() $f(r \mathbb {T})$

of the circle

$f(r \mathbb {T})$

of the circle

![]() $r \mathbb {T}$

under a meromorphic map

$r \mathbb {T}$

under a meromorphic map

![]() $f : \mathbb {D} \to \widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

. We denote by

$f : \mathbb {D} \to \widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

. We denote by

$$ \begin{align*}\mathrm{L}_{\mathrm{s}} (r\mathbb{T}):=\int \limits_{r \mathbb{T}} \frac{|dz|}{1+|z|^2}=\frac{2 \pi r}{1+r^2}\end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*}\mathrm{L}_{\mathrm{s}} (r\mathbb{T}):=\int \limits_{r \mathbb{T}} \frac{|dz|}{1+|z|^2}=\frac{2 \pi r}{1+r^2}\end{align*} $$

the spherical length of the circle

![]() $r \mathbb {T}$

.

$r \mathbb {T}$

.

Theorem 1.3 (Length Schwarz’s lemma for spherically convex functions)

Let

![]() $f{\kern-1.2pt}:{\kern-1.2pt}\mathbb {D} {\kern-1.2pt}\to{\kern-1.2pt} \widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

be a spherically convex function. Then

$f{\kern-1.2pt}:{\kern-1.2pt}\mathbb {D} {\kern-1.2pt}\to{\kern-1.2pt} \widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

be a spherically convex function. Then

Moreover, equality holds for some

![]() $0<r<1$

if and only if f is a spherical isometry.

$0<r<1$

if and only if f is a spherical isometry.

Remark 1.2 An upper bound for

![]() $\mathrm {L}_{\mathrm {s}} (f(r \mathbb {T}))$

for spherically convex functions

$\mathrm {L}_{\mathrm {s}} (f(r \mathbb {T}))$

for spherically convex functions

![]() $f : \mathbb {D} \to \widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

is

$f : \mathbb {D} \to \widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

is

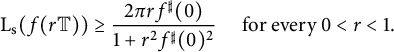

Similar to Corollary 1.2, there is also a more precise, but geometrically less natural lower bound for spherical length, which follows from Corollary 1.2 in conjunction with the isoperimetric inequality.

Theorem 1.4 Let

![]() $f:\mathbb {D} \to \widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

be spherically convex. Then

$f:\mathbb {D} \to \widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

be spherically convex. Then

$$ \begin{align*}\mathrm{L}_{\mathrm{s}} (f(r \mathbb{T})) \ge \frac{2\pi r f^{\sharp}(0)}{1+r^2 f^{\sharp }(0)^2} \quad \text{ for every } 0<r<1 .\end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*}\mathrm{L}_{\mathrm{s}} (f(r \mathbb{T})) \ge \frac{2\pi r f^{\sharp}(0)}{1+r^2 f^{\sharp }(0)^2} \quad \text{ for every } 0<r<1 .\end{align*} $$

Moreover, equality holds for any

![]() $0<r<1$

if f has the form

$0<r<1$

if f has the form

![]() $f(z)=T( \eta z)$

with

$f(z)=T( \eta z)$

with

![]() $T \in \operatorname {\mathrm {Rot}}(\widehat {\mathbb {C}})$

and

$T \in \operatorname {\mathrm {Rot}}(\widehat {\mathbb {C}})$

and

![]() $0<|\eta |\le 1$

.

$0<|\eta |\le 1$

.

Theorem 1.2 raises the question whether the ratio

$$ \begin{align} \mathcal{L}_{\mathrm{s}}(r) : = \frac{\mathrm{L}_{\mathrm{s}} (f(r \mathbb{T}))}{ \mathrm{L}_{\mathrm{s}} (r \mathbb{T})} \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \mathcal{L}_{\mathrm{s}}(r) : = \frac{\mathrm{L}_{\mathrm{s}} (f(r \mathbb{T}))}{ \mathrm{L}_{\mathrm{s}} (r \mathbb{T})} \end{align} $$

is monotonically increasing as a function of r. Note that (1.5) is the spherical analog of the quantity (1.1). While we cannot offer a full answer, we shall now show that such a monotonicity result does hold for spherically convex functions

![]() $f : \mathbb {D} \to \widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

which are centrally normalized:

$f : \mathbb {D} \to \widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

which are centrally normalized:

where

The important additional assumption is that

![]() $f"(0) = 0$

. The notion of central normalization and the insight of its relevance in the study of spherically convex function is due to Mejía and Pommerenke [Reference Mejía and Pommerenke16] building on earlier work of Minda and Wright [Reference Minda and Wright19], Chuaqui and Osgood [Reference Chuaqui and Osgood6], and Chuaqui, Osgood, and Pommerenke [Reference Chuaqui, Osgood and Pommerenke7]. According to [Reference Mejía and Pommerenke16, Theorem 4], for any spherically convex function f, there is always a unit disk automorphism

$f"(0) = 0$

. The notion of central normalization and the insight of its relevance in the study of spherically convex function is due to Mejía and Pommerenke [Reference Mejía and Pommerenke16] building on earlier work of Minda and Wright [Reference Minda and Wright19], Chuaqui and Osgood [Reference Chuaqui and Osgood6], and Chuaqui, Osgood, and Pommerenke [Reference Chuaqui, Osgood and Pommerenke7]. According to [Reference Mejía and Pommerenke16, Theorem 4], for any spherically convex function f, there is always a unit disk automorphism

![]() $\psi $

and a rotation

$\psi $

and a rotation

![]() $T \in \operatorname {\mathrm {Rot}}(\widehat {\mathbb {C}})$

such that

$T \in \operatorname {\mathrm {Rot}}(\widehat {\mathbb {C}})$

such that

![]() $T \circ f \circ \psi $

is centrally normalized.

$T \circ f \circ \psi $

is centrally normalized.

Theorem 1.5 Let

![]() $f: \mathbb {D} \to \widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

be a centrally normalized spherically convex function. Then

$f: \mathbb {D} \to \widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

be a centrally normalized spherically convex function. Then

![]() $\mathcal {L}_{\mathrm {s}}(r)$

is a strictly increasing function of

$\mathcal {L}_{\mathrm {s}}(r)$

is a strictly increasing function of

![]() $r \in (0,1)$

, unless f is a spherical isometry in which case

$r \in (0,1)$

, unless f is a spherical isometry in which case

![]() $\mathcal {L}_{\mathrm {s}}(r) \equiv 1$

.

$\mathcal {L}_{\mathrm {s}}(r) \equiv 1$

.

Theorem 1.5 is a spherical analog of the previously known monotonicity results for euclidean and hyperbolic length [Reference Kourou12, Reference Pólya and Szegő21].

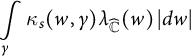

In addition to spherical length and spherical area, another important geometric quantity in spherical geometry is the total spherical curvature

$$ \begin{align*}\int \limits_{\gamma} \kappa_s(w,\gamma) \lambda_{\widehat{\mathbb{C}}}(w) \, |dw|\end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*}\int \limits_{\gamma} \kappa_s(w,\gamma) \lambda_{\widehat{\mathbb{C}}}(w) \, |dw|\end{align*} $$

of a curve

![]() $\gamma $

(see Section 2 and [Reference Minda18]). Roughly speaking, total spherical curvature measures how much the curve

$\gamma $

(see Section 2 and [Reference Minda18]). Roughly speaking, total spherical curvature measures how much the curve

![]() $\gamma $

diverges from being a spherical geodesic. We consider the ratio

$\gamma $

diverges from being a spherical geodesic. We consider the ratio

$$ \begin{align*}\Phi_s(r) : = \frac{\displaystyle\int\limits_{f(r \mathbb{T})} \kappa_s (w, f(r \mathbb{T}))\, |dw|}{\displaystyle\int\limits_{r \mathbb{T}} \kappa_s (z, r \mathbb{T}) \, |dz|}\end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*}\Phi_s(r) : = \frac{\displaystyle\int\limits_{f(r \mathbb{T})} \kappa_s (w, f(r \mathbb{T}))\, |dw|}{\displaystyle\int\limits_{r \mathbb{T}} \kappa_s (z, r \mathbb{T}) \, |dz|}\end{align*} $$

and prove the following monotonicity property.

Theorem 1.6 Let

![]() $f : \mathbb {D} \to \widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

be a centrally normalized spherically convex function. Then

$f : \mathbb {D} \to \widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

be a centrally normalized spherically convex function. Then

![]() $\Phi _s(r)$

is a strictly increasing function of

$\Phi _s(r)$

is a strictly increasing function of

![]() $r \in (0,1)$

, unless f is a spherical isometry in which case

$r \in (0,1)$

, unless f is a spherical isometry in which case

![]() $\Phi _s(r) \equiv 1$

.

$\Phi _s(r) \equiv 1$

.

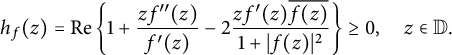

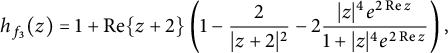

One of the crucial ingredients of the proofs of the above theorems is a basic result from [Reference Ma and Minda14, Theorem 4] which guarantees that a meromorphic univalent function f in

![]() $\mathbb {D}$

is spherically convex if and only if the auxiliary function

$\mathbb {D}$

is spherically convex if and only if the auxiliary function

$$ \begin{align} h_f(z):= \operatorname{\mathrm{Re}} \left\{ 1 + \frac{z f^{\prime \prime }(z)}{f^{\prime}(z)}-\frac{2z f^{\prime}(z) \overline{f(z)}}{1+\left| f(z) \right|{}^2} \right\} \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} h_f(z):= \operatorname{\mathrm{Re}} \left\{ 1 + \frac{z f^{\prime \prime }(z)}{f^{\prime}(z)}-\frac{2z f^{\prime}(z) \overline{f(z)}}{1+\left| f(z) \right|{}^2} \right\} \end{align} $$

has the property that

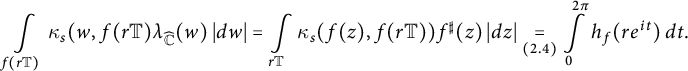

This characterization of spherical convexity has an elegant geometric interpretation in terms of the spherical curvature

![]() $\kappa _s(f(z), f(r \mathbb {T}))$

of the curve

$\kappa _s(f(z), f(r \mathbb {T}))$

of the curve

![]() $f(r \mathbb {T})$

at the point

$f(r \mathbb {T})$

at the point

![]() $f(z)$

,

$f(z)$

,

![]() $|z|=r$

, since

$|z|=r$

, since

(see (2.4)), so a meromorphic univalent function f in

![]() $\mathbb {D}$

is spherically convex if and only if

$\mathbb {D}$

is spherically convex if and only if

For further information on spherical convexity and spherically convex functions, we refer to Section 2 and also [Reference Kim and Minda10, Reference Ma and Minda14–Reference Mejía and Pommerenke16, Reference Minda18, Reference Sugawa24], as well as the recent work [Reference Kelgiannis9], where monotonicity results are proved regarding the elliptic area radius of

![]() $f( r \mathbb {D})$

and condenser capacity. Other variants of the Schwarz lemma for meromorphic functions can be found, e.g., in [Reference Dubinin8, Reference Solynin22].

$f( r \mathbb {D})$

and condenser capacity. Other variants of the Schwarz lemma for meromorphic functions can be found, e.g., in [Reference Dubinin8, Reference Solynin22].

The paper is structured in the following way. In Section 2, we recall a number of basic facts about spherical geometry and spherical convexity which are necessary for our investigations, including the spherical Gauss–Bonnet theorem and the spherical isoperimetric inequality. In Section 3, we study the auxiliary function

![]() $h_f$

defined in (1.6) and give a new characterization of spherical convexity as well as establish a sharp lower bound for the integral means of

$h_f$

defined in (1.6) and give a new characterization of spherical convexity as well as establish a sharp lower bound for the integral means of

![]() $h_f$

. A corresponding pointwise sharp lower estimate for

$h_f$

. A corresponding pointwise sharp lower estimate for

![]() $h_f$

has been given by Mejía and Pommerenke in their important work [Reference Mejía and Pommerenke16] on the Schwarzian derivative for spherically convex functions. While the estimate of Mejía and Pommerenke is valid only for centrally normalized functions, our “integrated” version does hold for any spherically convex function and possesses a natural geometric significance in terms of total geodesic curvature. The spherical Schwarz-type lemmas, Theorems 1.1 and 1.3, and Remark 1.2 are proved in Section 4. Then attention shifts to monotonicity results for spherically convex functions. In Section 5, we consider spherical area and prove Theorem 1.2 as well as Corollary 1.2 and Theorem 1.4. The monotonicity of spherical length (Theorem 1.5) and of total spherical curvature (Theorem 1.6) for centrally normalized spherically convex functions is established in Section 6. In a final Section 7, we illustrate by examples that spherical convexity is a basic requirement for Theorems 1.2, 1.5, and 1.6 and that central normalization is a necessary hypothesis for Theorem 1.6.

$h_f$

has been given by Mejía and Pommerenke in their important work [Reference Mejía and Pommerenke16] on the Schwarzian derivative for spherically convex functions. While the estimate of Mejía and Pommerenke is valid only for centrally normalized functions, our “integrated” version does hold for any spherically convex function and possesses a natural geometric significance in terms of total geodesic curvature. The spherical Schwarz-type lemmas, Theorems 1.1 and 1.3, and Remark 1.2 are proved in Section 4. Then attention shifts to monotonicity results for spherically convex functions. In Section 5, we consider spherical area and prove Theorem 1.2 as well as Corollary 1.2 and Theorem 1.4. The monotonicity of spherical length (Theorem 1.5) and of total spherical curvature (Theorem 1.6) for centrally normalized spherically convex functions is established in Section 6. In a final Section 7, we illustrate by examples that spherical convexity is a basic requirement for Theorems 1.2, 1.5, and 1.6 and that central normalization is a necessary hypothesis for Theorem 1.6.

2 Spherical convexity—Gauss–Bonnet formula—isoperimetric inequality

Suppose

![]() $f: \mathbb {D} \to \widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

is a meromorphic univalent function and

$f: \mathbb {D} \to \widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

is a meromorphic univalent function and

![]() $f(\mathbb {D})$

is a hyperbolic domain in

$f(\mathbb {D})$

is a hyperbolic domain in

![]() $\widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

.

$\widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

.

Lemma 2.1 [Reference Kim and Minda10, Theorem 1]

The spherical density

![]() $\left (1-|z|^2\right ) f^{\sharp }(z)$

is a superharmonic function on

$\left (1-|z|^2\right ) f^{\sharp }(z)$

is a superharmonic function on

![]() $\mathbb {D}$

if and only if

$\mathbb {D}$

if and only if

![]() $f(\mathbb {D})$

is a spherically convex domain.

$f(\mathbb {D})$

is a spherically convex domain.

Lemma 2.2 [Reference Kim and Minda10, p. 288]

If f is spherically convex on

![]() $\mathbb {D}$

, then

$\mathbb {D}$

, then

![]() $\left (1-|z|^2\right ) f^{\sharp }(z) \leq 1$

for every

$\left (1-|z|^2\right ) f^{\sharp }(z) \leq 1$

for every

![]() $z \in \mathbb {D}$

. Equality holds for some

$z \in \mathbb {D}$

. Equality holds for some

![]() $z \in \mathbb {D}$

if and only if f maps

$z \in \mathbb {D}$

if and only if f maps

![]() $\mathbb {D}$

onto a hemisphere and

$\mathbb {D}$

onto a hemisphere and

![]() $f(z)$

is the spherical center of the hemisphere.

$f(z)$

is the spherical center of the hemisphere.

Proposition 2.1 [Reference Ma and Minda14, Theorem 4]

Let

![]() $f :\mathbb {D} \to \widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

be a meromorphic univalent function. Then f is spherically convex if and only if

$f :\mathbb {D} \to \widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

be a meromorphic univalent function. Then f is spherically convex if and only if

$$ \begin{align*}h_f(z) = \operatorname{\mathrm{Re}} \left\{ 1 + \frac{z f^{\prime \prime}(z)}{f^{\prime}(z)} - 2 \frac{z f^{\prime}(z) \overline{f(z)}}{1+|f(z)|^2} \right\} \geq 0, \quad z \in \mathbb{D}.\end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*}h_f(z) = \operatorname{\mathrm{Re}} \left\{ 1 + \frac{z f^{\prime \prime}(z)}{f^{\prime}(z)} - 2 \frac{z f^{\prime}(z) \overline{f(z)}}{1+|f(z)|^2} \right\} \geq 0, \quad z \in \mathbb{D}.\end{align*} $$

Mejía and Pommerenke (see [Reference Mejía and Pommerenke16, equation (3.14)]) have proved that for any centrally normalized spherically convex function f,

$$ \begin{align} h_f(z) \geq \frac{1-|z|^2}{1+|z|^2} . \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} h_f(z) \geq \frac{1-|z|^2}{1+|z|^2} . \end{align} $$

In fact, it is not difficult for the reader to convince himself that equality can hold in (2.1) for some

![]() $z \in \mathbb {D}$

if and only if f is a spherical isometry.

$z \in \mathbb {D}$

if and only if f is a spherical isometry.

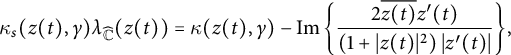

For a geometric interpretation of spherical convexity, we briefly discuss the notion of spherical curvature. A curve

![]() $\gamma $

on

$\gamma $

on

![]() $\widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

is said to have spherical curvature

$\widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

is said to have spherical curvature

![]() $\kappa _s(z, \gamma ) $

equal to

$\kappa _s(z, \gamma ) $

equal to

![]() $0$

at any of its points if and only if it is a spherical geodesic.

$0$

at any of its points if and only if it is a spherical geodesic.

Let

![]() $\gamma :z=z(t)$

be a

$\gamma :z=z(t)$

be a

![]() $\mathcal{C}^2$

curve on

$\mathcal{C}^2$

curve on

![]() $\widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

with everywhere nonvanishing tangent. The spherical curvature of

$\widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

with everywhere nonvanishing tangent. The spherical curvature of

![]() $\gamma $

at

$\gamma $

at

![]() $z(t)$

is

$z(t)$

is

$$ \begin{align*}\kappa_s (z(t), \gamma) \lambda_{\widehat{\mathbb{C}}} (z(t))= \kappa (z(t), \gamma) - \operatorname{\mathrm{Im}} \left\{ \frac{2 \overline{z(t)} z^{\prime}(t)}{\left(1+|z(t)|^2\right) |z^{\prime}(t)|} \right\}\!,\end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*}\kappa_s (z(t), \gamma) \lambda_{\widehat{\mathbb{C}}} (z(t))= \kappa (z(t), \gamma) - \operatorname{\mathrm{Im}} \left\{ \frac{2 \overline{z(t)} z^{\prime}(t)}{\left(1+|z(t)|^2\right) |z^{\prime}(t)|} \right\}\!,\end{align*} $$

where

![]() $\kappa (z(t), \gamma ) $

is the euclidean curvature of

$\kappa (z(t), \gamma ) $

is the euclidean curvature of

![]() $\gamma $

at

$\gamma $

at

![]() $z(t)$

.

$z(t)$

.

It can easily be calculated that the spherical curvature of

![]() $r \mathbb {T}$

at a point

$r \mathbb {T}$

at a point

![]() $z\in r\mathbb {T}$

is equal to

$z\in r\mathbb {T}$

is equal to

Proposition 2.2 [Reference Ma and Minda14, Theorem 3]

If

![]() $\Omega \subset \widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

has

$\Omega \subset \widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

has

![]() $\mathcal {C}^2 $

smooth boundary and

$\mathcal {C}^2 $

smooth boundary and

![]() $\Omega $

is spherically convex, then for all

$\Omega $

is spherically convex, then for all

![]() $z \in \partial \Omega $

,

$z \in \partial \Omega $

,

![]() $\kappa _s(z, \partial \Omega ) \geq 0$

.

$\kappa _s(z, \partial \Omega ) \geq 0$

.

Proposition 2.3 [Reference Ma and Minda14, Theorem 2]

Suppose

![]() $f:\mathbb {D} \to \widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

is a meromorphic univalent function and

$f:\mathbb {D} \to \widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

is a meromorphic univalent function and

![]() $\gamma : z=z(t)$

is a

$\gamma : z=z(t)$

is a

![]() $\mathcal {C}^2$

curve in

$\mathcal {C}^2$

curve in

![]() $\mathbb {D}$

. Then

$\mathbb {D}$

. Then

$$ \begin{align} &\kappa_s(f(z), f \circ \gamma) \left(1-|z|^2\right) f^{\sharp}(z)\\& \quad = \kappa_h(z, \gamma) - \left(1-|z|^2\right) \operatorname{\mathrm{Im}} \left\{ \left(2\frac{\bar{z}}{1-|z|^2}- \frac{f^{\prime \prime }(z)}{f^{\prime }(z)} + \frac{ 2 f^{\prime }(z) \overline{f(z)}}{1+|f(z)|^2} \right) \frac{z^{\prime}(t)}{|z^{\prime}(t)|} \right\}\!,\nonumber \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} &\kappa_s(f(z), f \circ \gamma) \left(1-|z|^2\right) f^{\sharp}(z)\\& \quad = \kappa_h(z, \gamma) - \left(1-|z|^2\right) \operatorname{\mathrm{Im}} \left\{ \left(2\frac{\bar{z}}{1-|z|^2}- \frac{f^{\prime \prime }(z)}{f^{\prime }(z)} + \frac{ 2 f^{\prime }(z) \overline{f(z)}}{1+|f(z)|^2} \right) \frac{z^{\prime}(t)}{|z^{\prime}(t)|} \right\}\!,\nonumber \end{align} $$

where

![]() $ \kappa _h$

denotes the hyperbolic curvature and

$ \kappa _h$

denotes the hyperbolic curvature and

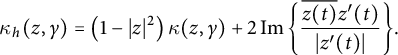

$$ \begin{align*}\kappa_h (z, \gamma) = \left(1-|z|^2\right) \kappa(z,\gamma) +2 \operatorname{\mathrm{Im}} \left\{ \frac{\overline{z(t)} z^{\prime }(t)}{|z^{\prime}(t)|}\right\}\!.\end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*}\kappa_h (z, \gamma) = \left(1-|z|^2\right) \kappa(z,\gamma) +2 \operatorname{\mathrm{Im}} \left\{ \frac{\overline{z(t)} z^{\prime }(t)}{|z^{\prime}(t)|}\right\}\!.\end{align*} $$

Let

![]() $f:\mathbb {D} \to \widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

be a meromorphic univalent function. For the definition of the function

$f:\mathbb {D} \to \widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

be a meromorphic univalent function. For the definition of the function

![]() $\Phi _s(r)$

, as stated in the Introduction, we will need the spherical curvature of

$\Phi _s(r)$

, as stated in the Introduction, we will need the spherical curvature of

![]() $f(r \mathbb {T})$

. Therefore, according to (2.3),

$f(r \mathbb {T})$

. Therefore, according to (2.3),

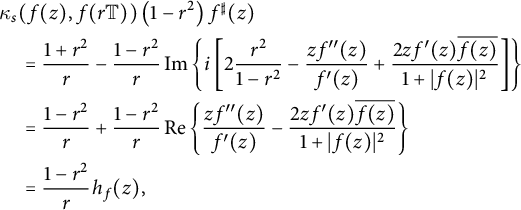

$$ \begin{align*} &\kappa_s(f(z), f(r \mathbb{T})) \left(1-r^2\right) f^{\sharp}(z)\\& \quad = \frac{1+r^2}{r} - \frac{1-r^2}{r} \operatorname{\mathrm{Im}} \left\{ i \left[ 2 \frac{r^2}{ 1-r^2} - \frac{z f^{\prime \prime }(z)}{f^{\prime }(z)} + \frac{ 2 z f^{\prime }(z) \overline{f(z)}}{1+|f(z)|^2} \right] \right\} \\& \quad = \frac{1-r^2}{r} + \frac{1-r^2}{r}\operatorname{\mathrm{Re}} \left\{ \frac{z f^{\prime \prime }(z)}{f^{\prime }(z)} - \frac{ 2 z f^{\prime }(z) \overline{f(z)}}{1+|f(z)|^2} \right\} \\& \quad =\frac{1-r^2}{r} h_f(z), \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} &\kappa_s(f(z), f(r \mathbb{T})) \left(1-r^2\right) f^{\sharp}(z)\\& \quad = \frac{1+r^2}{r} - \frac{1-r^2}{r} \operatorname{\mathrm{Im}} \left\{ i \left[ 2 \frac{r^2}{ 1-r^2} - \frac{z f^{\prime \prime }(z)}{f^{\prime }(z)} + \frac{ 2 z f^{\prime }(z) \overline{f(z)}}{1+|f(z)|^2} \right] \right\} \\& \quad = \frac{1-r^2}{r} + \frac{1-r^2}{r}\operatorname{\mathrm{Re}} \left\{ \frac{z f^{\prime \prime }(z)}{f^{\prime }(z)} - \frac{ 2 z f^{\prime }(z) \overline{f(z)}}{1+|f(z)|^2} \right\} \\& \quad =\frac{1-r^2}{r} h_f(z), \end{align*} $$

for

![]() $z=re^{it}, r \in (0,1), t \in [0,2\pi ]$

, and

$z=re^{it}, r \in (0,1), t \in [0,2\pi ]$

, and

![]() $\kappa (z,r\mathbb{T} ) = \frac {1}{r}$

. Hence,

$\kappa (z,r\mathbb{T} ) = \frac {1}{r}$

. Hence,

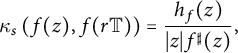

$$ \begin{align} \kappa_s\left(f(z), f(r \mathbb{T})\right) = \frac{h_f(z)}{|z|f^{\sharp}(z)}, \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \kappa_s\left(f(z), f(r \mathbb{T})\right) = \frac{h_f(z)}{|z|f^{\sharp}(z)}, \end{align} $$

where

![]() $z \in r \mathbb{T}$

. The total spherical curvature is a geometric quantity that measures how much a curve diverges from being spherically convex. From (2.2), the total spherical curvature of

$z \in r \mathbb{T}$

. The total spherical curvature is a geometric quantity that measures how much a curve diverges from being spherically convex. From (2.2), the total spherical curvature of

![]() $r \mathbb {T}$

is equal to

$r \mathbb {T}$

is equal to

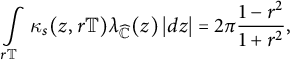

$$ \begin{align} \int\limits_{r \mathbb{T}} \kappa_s(z, r \mathbb{T}) \lambda_{\widehat{\mathbb{C}}}(z) \, |dz| =2 \pi \frac{1-r^2}{1+r^2}, \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \int\limits_{r \mathbb{T}} \kappa_s(z, r \mathbb{T}) \lambda_{\widehat{\mathbb{C}}}(z) \, |dz| =2 \pi \frac{1-r^2}{1+r^2}, \end{align} $$

and from (2.4), the total spherical curvature of

![]() $f(r \mathbb {T})$

is

$f(r \mathbb {T})$

is

$$ \begin{align} \int\limits_{f(r \mathbb{T})} \kappa_s(w, f(r \mathbb{T}) \lambda_{\widehat{\mathbb{C}}}(w) \, |dw| = \int\limits_{r \mathbb{T}} \kappa_s(f(z), f (r \mathbb{T})) f^{\sharp}(z) \, |dz| \underset{(2.4)}{=} \int\limits_{0}^{2 \pi} h_f(r e^{it}) \, dt. \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \int\limits_{f(r \mathbb{T})} \kappa_s(w, f(r \mathbb{T}) \lambda_{\widehat{\mathbb{C}}}(w) \, |dw| = \int\limits_{r \mathbb{T}} \kappa_s(f(z), f (r \mathbb{T})) f^{\sharp}(z) \, |dz| \underset{(2.4)}{=} \int\limits_{0}^{2 \pi} h_f(r e^{it}) \, dt. \end{align} $$

For more information on spherical convexity and spherical curvature, the reader may refer to [Reference Ma and Minda14, Reference Ma, Minda and Mejía15, Reference Minda18].

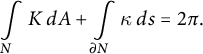

In the proof of Theorem 1.6, we will use the Gauss–Bonnet formula in the following form (see [Reference Spivak23, Theorem 6.5]). Let M be an oriented two-dimensional Riemannian manifold with Gaussian curvature K and volume element

![]() $d A$

. Let

$d A$

. Let

![]() $N \subset M $

be a compact two-dimensional manifold with boundary which is diffeomorphic to a subset of

$N \subset M $

be a compact two-dimensional manifold with boundary which is diffeomorphic to a subset of

![]() $\mathbb {R}^2$

and whose boundary is connected. Let

$\mathbb {R}^2$

and whose boundary is connected. Let

![]() $ds$

be the volume element of

$ds$

be the volume element of

![]() $\partial N $

, and let

$\partial N $

, and let

![]() $\kappa $

be the signed geodesic curvature of

$\kappa $

be the signed geodesic curvature of

![]() $\partial N$

. Then

$\partial N$

. Then

$$ \begin{align} \int\limits_{N} K \, dA + \int\limits_{\partial N} \kappa \, ds = 2 \pi. \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \int\limits_{N} K \, dA + \int\limits_{\partial N} \kappa \, ds = 2 \pi. \end{align} $$

The Riemann sphere

![]() $\widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

endowed with the spherical metric is a two-dimensional Riemannian manifold of constant Gaussian curvature equal to

$\widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

endowed with the spherical metric is a two-dimensional Riemannian manifold of constant Gaussian curvature equal to

![]() $4$

. If

$4$

. If

![]() $\Omega $

is a hyperbolic domain in

$\Omega $

is a hyperbolic domain in

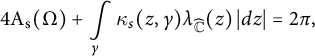

![]() $\widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

, the Gauss–Bonnet formula (2.7) takes the form

$\widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

, the Gauss–Bonnet formula (2.7) takes the form

$$ \begin{align} 4 \mathrm{A}_{\mathrm{s}} (\Omega) + \int\limits_{\gamma} \kappa_s (z, \gamma) \lambda_{\widehat{\mathbb{C}}}(z) \, |dz| = 2 \pi, \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} 4 \mathrm{A}_{\mathrm{s}} (\Omega) + \int\limits_{\gamma} \kappa_s (z, \gamma) \lambda_{\widehat{\mathbb{C}}}(z) \, |dz| = 2 \pi, \end{align} $$

where

![]() $\gamma $

is the boundary of

$\gamma $

is the boundary of

![]() $\Omega $

assuming that it is a smooth, simple, and closed curve in

$\Omega $

assuming that it is a smooth, simple, and closed curve in

![]() $\widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

.

$\widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

.

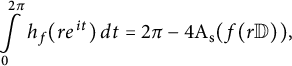

Applying the Gauss–Bonnet formula (2.8) to

![]() $f( r \mathbb {D})$

viewed as a two-dimensional manifold with boundary on the Riemann surface of f, we obtain

$f( r \mathbb {D})$

viewed as a two-dimensional manifold with boundary on the Riemann surface of f, we obtain

$$ \begin{align} \int\limits_0^{2 \pi} h_f(r e^{it}) \, dt = 2 \pi - 4 \mathrm{A}_{\mathrm{s}} (f(r \mathbb{D})), \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \int\limits_0^{2 \pi} h_f(r e^{it}) \, dt = 2 \pi - 4 \mathrm{A}_{\mathrm{s}} (f(r \mathbb{D})), \end{align} $$

where

![]() $\mathrm {A}_{\mathrm {s}} (f(r \mathbb {D}) )$

is the spherical area of

$\mathrm {A}_{\mathrm {s}} (f(r \mathbb {D}) )$

is the spherical area of

![]() $f(r \mathbb {D})$

.

$f(r \mathbb {D})$

.

Last but not least, in order to prove lower bounds for the spherical length, we use the isoperimetric inequality of spherical geometry (see [Reference Osserman20]). Suppose D is a simply connected smooth subdomain of

![]() $\widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

. Then

$\widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

. Then

3 The function

$h_f$

$h_f$

For our purposes, the following characterization of spherically convex functions in terms of the function

$$ \begin{align*}h_f(z) = \operatorname{\mathrm{Re}} \left\{ 1+ z \frac{f^{\prime \prime }(z)}{f^{\prime}(z)} - \frac{2z \overline{f(z)} f^{\prime}(z)}{1+|f(z)|^2} \right\}\end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*}h_f(z) = \operatorname{\mathrm{Re}} \left\{ 1+ z \frac{f^{\prime \prime }(z)}{f^{\prime}(z)} - \frac{2z \overline{f(z)} f^{\prime}(z)}{1+|f(z)|^2} \right\}\end{align*} $$

turns out to be useful.

Theorem 3.1 Let

![]() $f: \mathbb {D} \to \widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

be a meromorphic univalent function. Then

$f: \mathbb {D} \to \widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

be a meromorphic univalent function. Then

In particular, f is spherically convex if and only if

![]() $h_f$

is superharmonic on

$h_f$

is superharmonic on

![]() $\mathbb {D}$

. In this case,

$\mathbb {D}$

. In this case,

![]() $h_f$

is strictly superharmonic, so

$h_f$

is strictly superharmonic, so

![]() $\Delta h_f<0$

in

$\Delta h_f<0$

in

![]() $\mathbb {D}$

.

$\mathbb {D}$

.

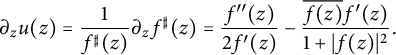

Proof Let

![]() $u(z): =\log f^{\sharp } (z)$

, so

$u(z): =\log f^{\sharp } (z)$

, so

![]() $f^{\sharp } (z)= e^{u(z)}$

. Taking the derivative of u with respect to z, we obtain

$f^{\sharp } (z)= e^{u(z)}$

. Taking the derivative of u with respect to z, we obtain

$$ \begin{align*}\partial_z u(z) = \frac{1}{f^{\sharp} (z)} \partial_z f^{\sharp} (z)= \frac{f^{\prime \prime }(z)}{2 f^{\prime}(z)} - \frac{ \overline{f(z)} f^{\prime}(z)}{1+|f(z)|^2} .\end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*}\partial_z u(z) = \frac{1}{f^{\sharp} (z)} \partial_z f^{\sharp} (z)= \frac{f^{\prime \prime }(z)}{2 f^{\prime}(z)} - \frac{ \overline{f(z)} f^{\prime}(z)}{1+|f(z)|^2} .\end{align*} $$

This implies that the real part of

![]() $v(z) : = 1+2z \partial _z u(z)$

is exactly

$v(z) : = 1+2z \partial _z u(z)$

is exactly

![]() $h_f$

. Now, u is a solution of the Liouville equation

$h_f$

. Now, u is a solution of the Liouville equation

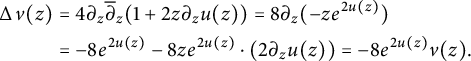

Hence, the Laplacian of v is given by

$$ \begin{align*} \operatorname{\mathrm{\Delta}} v(z) &= 4 \partial_z \overline{\partial}_z (1+2 z \partial_z u(z)) = 8 \partial_z (-z e^{2u(z)}) \\ &= -8 e^{2u(z)} -8z e^{2u(z)} \cdot \left(2 \partial_z u(z)\right) = -8 e^{2 u(z)} v(z) . \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} \operatorname{\mathrm{\Delta}} v(z) &= 4 \partial_z \overline{\partial}_z (1+2 z \partial_z u(z)) = 8 \partial_z (-z e^{2u(z)}) \\ &= -8 e^{2u(z)} -8z e^{2u(z)} \cdot \left(2 \partial_z u(z)\right) = -8 e^{2 u(z)} v(z) . \end{align*} $$

Taking the real part gives (3.1). In particular,

![]() $\operatorname {\mathrm {\Delta }} h_f(z) \leq 0$

if and only if

$\operatorname {\mathrm {\Delta }} h_f(z) \leq 0$

if and only if

![]() $h_f(z) \ge 0$

, so f is a spherically convex function if and only if

$h_f(z) \ge 0$

, so f is a spherically convex function if and only if

![]() $h_f$

is superharmonic. Suppose f is spherically convex. If

$h_f$

is superharmonic. Suppose f is spherically convex. If

![]() $h_f(z_0)=0$

for some

$h_f(z_0)=0$

for some

![]() $z_0 \in \mathbb {D}$

, then

$z_0 \in \mathbb {D}$

, then

![]() $h_f$

would attain its global minimum at

$h_f$

would attain its global minimum at

![]() $z_0$

and hence would be constant

$z_0$

and hence would be constant

![]() $0$

by the minimum principle for superharmonic functions. However,

$0$

by the minimum principle for superharmonic functions. However,

![]() $h_f(0)=1$

. This contradiction shows that

$h_f(0)=1$

. This contradiction shows that

![]() $h_f$

is strictly positive on

$h_f$

is strictly positive on

![]() $\mathbb {D}$

. Since f is univalent,

$\mathbb {D}$

. Since f is univalent,

![]() $f^{\sharp }$

never vanishes, and hence

$f^{\sharp }$

never vanishes, and hence

![]() $h_f$

is strictly superharmonic.

$h_f$

is strictly superharmonic.

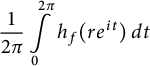

Theorem 3.1 implies that for any spherically convex function

![]() $f : \mathbb {D} \to \widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

, the integral means

$f : \mathbb {D} \to \widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

, the integral means

$$ \begin{align*}\frac{1}{2\pi}\int\limits_0^{2 \pi} h_f(r e^{it}) \, dt\end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*}\frac{1}{2\pi}\int\limits_0^{2 \pi} h_f(r e^{it}) \, dt\end{align*} $$

are strictly decreasing and log-concave. The following result provides the sharp lower bound for these integral means.

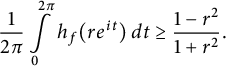

Theorem 3.2 Let

![]() $f: \mathbb {D} \to \widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

be spherically convex. Then, for any

$f: \mathbb {D} \to \widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

be spherically convex. Then, for any

![]() $r \in (0,1)$

,

$r \in (0,1)$

,

$$ \begin{align} \frac{1}{2\pi}\int\limits_0^{2 \pi} h_f(r e^{it}) \, dt \ge \frac{1-r^2}{1+r^2}. \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \frac{1}{2\pi}\int\limits_0^{2 \pi} h_f(r e^{it}) \, dt \ge \frac{1-r^2}{1+r^2}. \end{align} $$

For fixed

![]() $r \in (0,1)$

, equality holds in (3.2) if and only if f is a spherical isometry.

$r \in (0,1)$

, equality holds in (3.2) if and only if f is a spherical isometry.

Theorem 3.2 is an integrated version of the Mejía–Pommerenke inequality (2.1), but with the additional benefit that we do not need to assume central normalization. The estimate (3.2) has a natural geometric interpretation by observing that the integral expression is precisely the normalized total spherical curvature of

![]() $f(r \mathbb {T})$

, whereas the right-hand side is the normalized total spherical curvature of the circle

$f(r \mathbb {T})$

, whereas the right-hand side is the normalized total spherical curvature of the circle

![]() $r \mathbb {T}$

(see Section 2).

$r \mathbb {T}$

(see Section 2).

Proof Since

![]() $h_{T \circ f}=h_f$

for any

$h_{T \circ f}=h_f$

for any

![]() $T \in \operatorname {\mathrm {Rot}}(\widehat {\mathbb {C}})$

, we may assume

$T \in \operatorname {\mathrm {Rot}}(\widehat {\mathbb {C}})$

, we may assume

![]() $f(0)=0$

. Fix

$f(0)=0$

. Fix

![]() $t \in [0,2 \pi ]$

. We apply a beautiful idea from [Reference Mejía and Pommerenke16, Theorem 1 and equation (3.13)], namely that the function

$t \in [0,2 \pi ]$

. We apply a beautiful idea from [Reference Mejía and Pommerenke16, Theorem 1 and equation (3.13)], namely that the function

$$ \begin{align*}p_t(z): = 1 + z\frac{f^{\prime \prime}(z)}{f^{\prime}(z)} -2 \frac{z f^{\prime}(z) \overline{f(e^{2it}\bar{z})}}{1+f(z) \overline{f(e^{2it}\bar{z})}}\end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*}p_t(z): = 1 + z\frac{f^{\prime \prime}(z)}{f^{\prime}(z)} -2 \frac{z f^{\prime}(z) \overline{f(e^{2it}\bar{z})}}{1+f(z) \overline{f(e^{2it}\bar{z})}}\end{align*} $$

belongs to the Carathéodory class

since

![]() $\operatorname {\mathrm {Re}} p_t(r e^{it}) = h_f(r e^{it})$

. Hence,

$\operatorname {\mathrm {Re}} p_t(r e^{it}) = h_f(r e^{it})$

. Hence,

![]() $p_t(e^{it} z)$

also belongs to

$p_t(e^{it} z)$

also belongs to

![]() $\mathcal {P}$

. In view of the convexity and compactness of

$\mathcal {P}$

. In view of the convexity and compactness of

![]() $\mathcal {P}$

, the function

$\mathcal {P}$

, the function

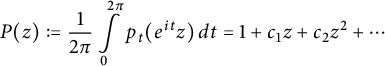

$$ \begin{align*}P(z): =\frac{1}{2\pi} \int\limits_0^{2 \pi} p_t(e^{it}z) \, dt= 1 + c_1 z+ c_2 z^2+ \cdots\end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*}P(z): =\frac{1}{2\pi} \int\limits_0^{2 \pi} p_t(e^{it}z) \, dt= 1 + c_1 z+ c_2 z^2+ \cdots\end{align*} $$

also lies in

![]() $\mathcal {P}$

. We claim that

$\mathcal {P}$

. We claim that

![]() $c_1=0$

. In order to see this, recall that by assumption

$c_1=0$

. In order to see this, recall that by assumption

![]() $f(0)=0$

, so f is holomorphic in

$f(0)=0$

, so f is holomorphic in

![]() $\mathbb {D}$

with

$\mathbb {D}$

with

![]() $f'\not =0$

. Then

$f'\not =0$

. Then

![]() $z w f"(zw)/f'(zw)$

is a holomorphic function of w in a neighborhood of the closed unit disk, so the mean value property implies

$z w f"(zw)/f'(zw)$

is a holomorphic function of w in a neighborhood of the closed unit disk, so the mean value property implies

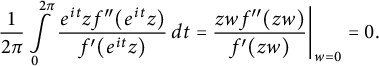

$$ \begin{align*}\frac{1}{2\pi} \int\limits_{0}^{2 \pi} \frac{e^{it} z f^{\prime \prime}(e^{it}z) }{f^{\prime} ( e^{it}z)} \, dt = \frac{zw f^{\prime \prime}(zw) }{f^{\prime}(zw) } \bigg|_{w=0} =0 .\end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*}\frac{1}{2\pi} \int\limits_{0}^{2 \pi} \frac{e^{it} z f^{\prime \prime}(e^{it}z) }{f^{\prime} ( e^{it}z)} \, dt = \frac{zw f^{\prime \prime}(zw) }{f^{\prime}(zw) } \bigg|_{w=0} =0 .\end{align*} $$

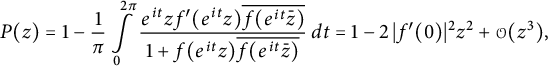

Hence,

using once more that

![]() $f(0)=0$

. Thus, the function

$f(0)=0$

. Thus, the function

![]() $(P-1)/(P+1) : \mathbb {D} \to \mathbb {D}$

has a zero of order at least 2 at

$(P-1)/(P+1) : \mathbb {D} \to \mathbb {D}$

has a zero of order at least 2 at

![]() $z=0$

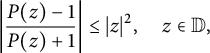

, so the Schwarz lemma implies

$z=0$

, so the Schwarz lemma implies

$$ \begin{align*}\left| \frac{P(z)-1}{P(z)+1} \right| \leq |z|^2, \quad z \in \mathbb{D} ,\end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*}\left| \frac{P(z)-1}{P(z)+1} \right| \leq |z|^2, \quad z \in \mathbb{D} ,\end{align*} $$

with equality at one point if and only if P has the form

for some

![]() $|\omega |=1$

. We conclude that

$|\omega |=1$

. We conclude that

Equality for the left inequality holds if and only if

![]() $\omega =-1$

(resp.

$\omega =-1$

(resp.

![]() $|f'(0)|=1$

). By Lemma 2.2, this is the case if and only if

$|f'(0)|=1$

). By Lemma 2.2, this is the case if and only if

![]() $f(z)=\eta z$

for some

$f(z)=\eta z$

for some

![]() $|\eta |=1$

.

$|\eta |=1$

.

The Gauss–Bonnet formula (2.9) provides us with the following result.

Proposition 3.1 Let

![]() $f:\mathbb {D} \to \widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

be a meromorphic univalent function. Then

$f:\mathbb {D} \to \widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

be a meromorphic univalent function. Then

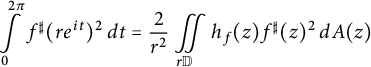

$$ \begin{align} \int\limits_{0}^{2 \pi} f^{\sharp}(re^{it})^2 \,dt = \frac{2}{r^2} \iint\limits_{r \mathbb{D}} h_f(z) f^{\sharp}(z)^2 \,dA(z) \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \int\limits_{0}^{2 \pi} f^{\sharp}(re^{it})^2 \,dt = \frac{2}{r^2} \iint\limits_{r \mathbb{D}} h_f(z) f^{\sharp}(z)^2 \,dA(z) \end{align} $$

for any

![]() $r \in (0,1)$

.

$r \in (0,1)$

.

Proof Taking the derivative w.r.t. r in the Gauss–Bonnet formula (2.9), we obtain

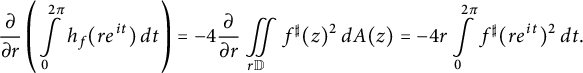

$$ \begin{align} \frac{\partial}{\partial r} \left( \int\limits_0^{2\pi} h_f(r e^{it}) \, dt \right)= -4 \frac{\partial}{\partial r} \iint\limits_{r \mathbb{D}} f^{\sharp}(z)^2 \, dA(z) = -4 r \int\limits_{0}^{2 \pi} f^{\sharp}(re^{it})^2 \, dt . \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \frac{\partial}{\partial r} \left( \int\limits_0^{2\pi} h_f(r e^{it}) \, dt \right)= -4 \frac{\partial}{\partial r} \iint\limits_{r \mathbb{D}} f^{\sharp}(z)^2 \, dA(z) = -4 r \int\limits_{0}^{2 \pi} f^{\sharp}(re^{it})^2 \, dt . \end{align} $$

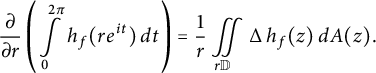

By Green’s formula, we also see that

$$ \begin{align*}\frac{\partial}{\partial r} \left( \int\limits_{0}^{2\pi} h_f(r e^{it}) \, dt \right) = \frac{1}{r} \iint\limits_{r \mathbb{D}} \operatorname{\mathrm{\Delta}} h_f(z) \, dA(z).\end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*}\frac{\partial}{\partial r} \left( \int\limits_{0}^{2\pi} h_f(r e^{it}) \, dt \right) = \frac{1}{r} \iint\limits_{r \mathbb{D}} \operatorname{\mathrm{\Delta}} h_f(z) \, dA(z).\end{align*} $$

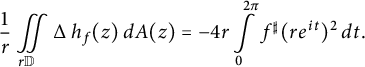

Together with (3.4), this yields

$$ \begin{align*}\frac{1}{r} \iint\limits_{r \mathbb{D}} \operatorname{\mathrm{\Delta}} h_f(z) \, dA(z) = -4 r \int\limits_{0}^{2 \pi} f^{\sharp}(re^{it})^2 \, dt . \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*}\frac{1}{r} \iint\limits_{r \mathbb{D}} \operatorname{\mathrm{\Delta}} h_f(z) \, dA(z) = -4 r \int\limits_{0}^{2 \pi} f^{\sharp}(re^{it})^2 \, dt . \end{align*} $$

Since

![]() $\Delta h_f=-8 (f^{\sharp })^2 h_f$

by Theorem 3.1, we see that (3.3) holds.

$\Delta h_f=-8 (f^{\sharp })^2 h_f$

by Theorem 3.1, we see that (3.3) holds.

4 Proofs of the spherical Schwarz lemmas

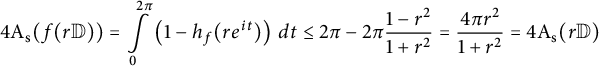

Proof of Theorem 1.1

Let

![]() $f : \mathbb {D} \to \widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

be a spherically convex function, and let

$f : \mathbb {D} \to \widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

be a spherically convex function, and let

![]() $0<r<1$

. The Gauss–Bonnet formula (2.9) and Theorem 3.2 imply

$0<r<1$

. The Gauss–Bonnet formula (2.9) and Theorem 3.2 imply

$$ \begin{align*}4 \mathrm{A}_{\mathrm{s}} (f(r \mathbb{D}))=\int \limits_{0}^{2\pi} \left(1- h_f(r e^{it}) \right) \, dt \le 2\pi -2 \pi \frac{1-r^2}{1+r^2} = \frac{4\pi r^2}{1+r^2} = 4 \mathrm{A}_{\mathrm{s}} (r \mathbb{D})\end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*}4 \mathrm{A}_{\mathrm{s}} (f(r \mathbb{D}))=\int \limits_{0}^{2\pi} \left(1- h_f(r e^{it}) \right) \, dt \le 2\pi -2 \pi \frac{1-r^2}{1+r^2} = \frac{4\pi r^2}{1+r^2} = 4 \mathrm{A}_{\mathrm{s}} (r \mathbb{D})\end{align*} $$

with equality for some

![]() $r \in (0,1)$

if and only if

$r \in (0,1)$

if and only if

![]() $f \in \operatorname {\mathrm {Rot}}(\widehat {\mathbb {C}})$

.

$f \in \operatorname {\mathrm {Rot}}(\widehat {\mathbb {C}})$

.

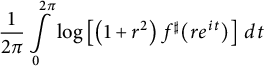

For the proof of Theorem 1.3, we first derive an auxiliary lemma.

Lemma 4.1 Let

![]() $f : \mathbb {D} \to \widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

be a spherically convex function. Then the integral mean

$f : \mathbb {D} \to \widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

be a spherically convex function. Then the integral mean

$$ \begin{align*}\frac{1}{2\pi} \int \limits_0^{2\pi} \log \left[ \left(1+r^2\right) f^{\sharp}(r e^{it})\right] \, dt\end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*}\frac{1}{2\pi} \int \limits_0^{2\pi} \log \left[ \left(1+r^2\right) f^{\sharp}(r e^{it})\right] \, dt\end{align*} $$

is strictly increasing as a function of r unless

![]() $f \in \operatorname {\mathrm {Rot}}(\widehat {\mathbb {C}})$

.

$f \in \operatorname {\mathrm {Rot}}(\widehat {\mathbb {C}})$

.

Proof It is easy to prove that

The result therefore follows from Theorem 3.2.

Proof of Theorem 1.3

Let

![]() $f : \mathbb {D} \to \widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

be a spherically convex function, and let

$f : \mathbb {D} \to \widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

be a spherically convex function, and let

![]() $0<r<1$

. Then

$0<r<1$

. Then

$$ \begin{align*} \frac{1}{2\pi} \mathrm{L}_{\mathrm{s}} (f(r \mathbb{T})) (1+r^2) &= r \left(1+r^2\right) \frac{1}{2\pi} \int \limits_{0}^{2\pi} f^{\sharp}(r e^{it}) \, dt \\ &= \frac{r}{2\pi} \int \limits_0^{2\pi} \exp \left( \log \left[ \left(1+r^2\right) f^{\sharp}(r e^{it}) \right] \right) \, dt \\ & \ge r \cdot \exp \left( \frac{1}{2\pi} \int \limits_{0}^{2\pi} \log \left[ \left(1+r^2\right) f^{\sharp}(r e^{it}) \right] \, dt \right) \\ & \ge r \cdot\exp \left( \frac{1}{2\pi} \int \limits_{0}^{2\pi} \log \left[ f^{\sharp}(0) \right] \, dt \right)\\ &= r f^{\sharp}(0) , \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} \frac{1}{2\pi} \mathrm{L}_{\mathrm{s}} (f(r \mathbb{T})) (1+r^2) &= r \left(1+r^2\right) \frac{1}{2\pi} \int \limits_{0}^{2\pi} f^{\sharp}(r e^{it}) \, dt \\ &= \frac{r}{2\pi} \int \limits_0^{2\pi} \exp \left( \log \left[ \left(1+r^2\right) f^{\sharp}(r e^{it}) \right] \right) \, dt \\ & \ge r \cdot \exp \left( \frac{1}{2\pi} \int \limits_{0}^{2\pi} \log \left[ \left(1+r^2\right) f^{\sharp}(r e^{it}) \right] \, dt \right) \\ & \ge r \cdot\exp \left( \frac{1}{2\pi} \int \limits_{0}^{2\pi} \log \left[ f^{\sharp}(0) \right] \, dt \right)\\ &= r f^{\sharp}(0) , \end{align*} $$

where we have first used Jensen’s inequality and then Lemma 4.1. Equality holds if and only if

![]() $f \in \operatorname {\mathrm {Rot}}(\widehat {\mathbb {C}})$

. Hence,

$f \in \operatorname {\mathrm {Rot}}(\widehat {\mathbb {C}})$

. Hence,

and equality holds if and only if

![]() $f \in \operatorname {\mathrm {Rot}}(\widehat {\mathbb {C}})$

.

$f \in \operatorname {\mathrm {Rot}}(\widehat {\mathbb {C}})$

.

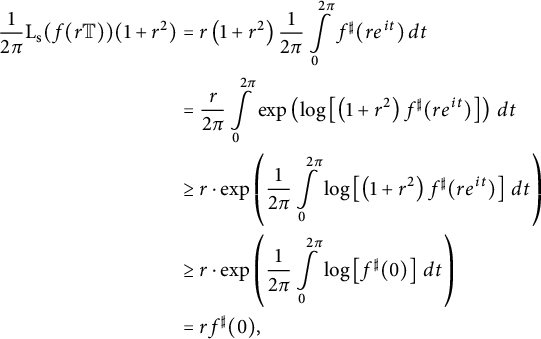

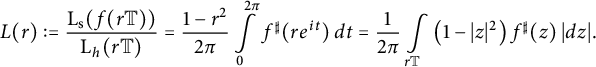

Proof of Remark 1.2

We apply Lemma 2.1. Let us denote by

![]() $\operatorname {\mathrm {L}}_h $

the length of a curve in

$\operatorname {\mathrm {L}}_h $

the length of a curve in

![]() $\mathbb {D}$

with respect to the hyperbolic metric

$\mathbb {D}$

with respect to the hyperbolic metric

$$ \begin{align*}\frac{|dz|}{1-|z|^2}\end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*}\frac{|dz|}{1-|z|^2}\end{align*} $$

of the unit disk. Set

$$ \begin{align*}L(r):= \frac{\mathrm{L}_{\mathrm{s}} (f(r \mathbb{T}))}{\operatorname{\mathrm{L}}_h (r \mathbb{T})} = \frac{1-r^2}{2 \pi} \int\limits_{0}^{2 \pi} f^{\sharp}(r e^{it}) \, dt= \frac{1}{2 \pi} \int\limits_{r \mathbb{T}} \left(1-|z|^2\right) f^{\sharp}(z)\, |dz| .\end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*}L(r):= \frac{\mathrm{L}_{\mathrm{s}} (f(r \mathbb{T}))}{\operatorname{\mathrm{L}}_h (r \mathbb{T})} = \frac{1-r^2}{2 \pi} \int\limits_{0}^{2 \pi} f^{\sharp}(r e^{it}) \, dt= \frac{1}{2 \pi} \int\limits_{r \mathbb{T}} \left(1-|z|^2\right) f^{\sharp}(z)\, |dz| .\end{align*} $$

According to Lemma 2.1,

![]() $\left (1-|z|^2\right ) f^{\sharp }(z)$

is a superharmonic function on

$\left (1-|z|^2\right ) f^{\sharp }(z)$

is a superharmonic function on

![]() $\mathbb {D}$

if and only if

$\mathbb {D}$

if and only if

![]() $f(\mathbb {D})$

is a spherically convex domain. Since f is a spherically convex function,

$f(\mathbb {D})$

is a spherically convex domain. Since f is a spherically convex function,

![]() $L(r)$

is the mean value of a superharmonic function and hence decreasing. Therefore,

$L(r)$

is the mean value of a superharmonic function and hence decreasing. Therefore,

and hence

for all

![]() $r \in (0,1)$

.

$r \in (0,1)$

.

5 Monotonicity of spherical area and length

Suppose

![]() $f : \mathbb {D} \to \widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

is a spherically convex function.

$f : \mathbb {D} \to \widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

is a spherically convex function.

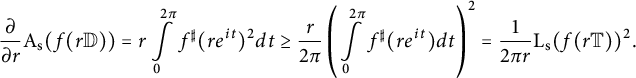

Proof of Theorem 1.2

With the use of the Cauchy–Schwarz inequality, we obtain a lower bound for the derivative

$$ \begin{align*} \frac{\partial}{\partial r} \mathrm{A}_{\mathrm{s}} (f(r \mathbb{D})) &= r \int \limits_{0}^{2 \pi} f^{\sharp }(r e^{it})^2 dt \geq \frac{r}{2\pi} \left(\int \limits_{0}^{2 \pi} f^{\sharp }(r e^{it}) dt \right)^2 =\frac{1}{2\pi r } \mathrm{L}_{\mathrm{s}} (f(r \mathbb{T}))^2. \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} \frac{\partial}{\partial r} \mathrm{A}_{\mathrm{s}} (f(r \mathbb{D})) &= r \int \limits_{0}^{2 \pi} f^{\sharp }(r e^{it})^2 dt \geq \frac{r}{2\pi} \left(\int \limits_{0}^{2 \pi} f^{\sharp }(r e^{it}) dt \right)^2 =\frac{1}{2\pi r } \mathrm{L}_{\mathrm{s}} (f(r \mathbb{T}))^2. \end{align*} $$

Utilizing the isoperimetric inequality (2.10), it follows

We aim to find a lower bound of the derivative of the function

![]() $\mathcal {A}_{\mathrm {s}} (r) = \frac {1+r^2}{\pi r^2} \mathrm {A}_{\mathrm {s}} (f(r \mathbb {D})) $

in order to prove its monotonicity. Accordingly, we compute with the help of (5.1)

$\mathcal {A}_{\mathrm {s}} (r) = \frac {1+r^2}{\pi r^2} \mathrm {A}_{\mathrm {s}} (f(r \mathbb {D})) $

in order to prove its monotonicity. Accordingly, we compute with the help of (5.1)

$$ \begin{align} \begin{aligned} \mathcal{A}_{\mathrm{s}}^{\prime} (r) &= -\frac{2}{\pi r^3} \mathrm{A}_{\mathrm{s}} (f (r \mathbb{D}) )+ \frac{1+r^2}{\pi r^2} \frac{\partial }{\partial r} \mathrm{A}_{\mathrm{s}} (f(r \mathbb{D})) \\ &\geq\frac{2}{\pi r^3} \mathrm{A}_{\mathrm{s}} (f(r \mathbb{D})) \left(-1 +\frac{1+r^2}{\pi} \left(\pi - \mathrm{A}_{\mathrm{s}} (f (r \mathbb{D}))\right) \right) \\ &=\frac{2}{\pi r} \mathrm{A}_{\mathrm{s}} (f(r \mathbb{D})) \left(1- \frac{1+r^2}{\pi r^2} \mathrm{A}_{\mathrm{s}} (f(r \mathbb{D})) \right) \geq 0 \end{aligned} \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \begin{aligned} \mathcal{A}_{\mathrm{s}}^{\prime} (r) &= -\frac{2}{\pi r^3} \mathrm{A}_{\mathrm{s}} (f (r \mathbb{D}) )+ \frac{1+r^2}{\pi r^2} \frac{\partial }{\partial r} \mathrm{A}_{\mathrm{s}} (f(r \mathbb{D})) \\ &\geq\frac{2}{\pi r^3} \mathrm{A}_{\mathrm{s}} (f(r \mathbb{D})) \left(-1 +\frac{1+r^2}{\pi} \left(\pi - \mathrm{A}_{\mathrm{s}} (f (r \mathbb{D}))\right) \right) \\ &=\frac{2}{\pi r} \mathrm{A}_{\mathrm{s}} (f(r \mathbb{D})) \left(1- \frac{1+r^2}{\pi r^2} \mathrm{A}_{\mathrm{s}} (f(r \mathbb{D})) \right) \geq 0 \end{aligned} \end{align} $$

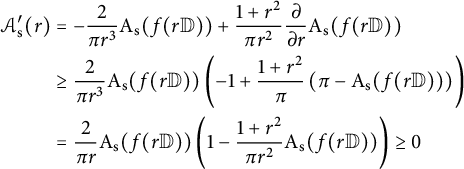

due to Theorem 1.1. As a result,

![]() $\mathcal {A}_{\mathrm {s}}(r)$

is increasing in

$\mathcal {A}_{\mathrm {s}}(r)$

is increasing in

![]() $(0,1)$

. Now, let us assume that

$(0,1)$

. Now, let us assume that

![]() $\mathcal {A}_{\mathrm {s}}^{\prime } (\xi ) = 0$

for some

$\mathcal {A}_{\mathrm {s}}^{\prime } (\xi ) = 0$

for some

![]() $\xi \in (0,1)$

. Then

$\xi \in (0,1)$

. Then

$$ \begin{align*}\mathrm{A}_{\mathrm{s}} (f(\xi \mathbb{D})) = \frac{\pi \xi^2}{1+\xi^2} = \mathrm{A}_{\mathrm{s}} (\xi \mathbb{D}),\end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*}\mathrm{A}_{\mathrm{s}} (f(\xi \mathbb{D})) = \frac{\pi \xi^2}{1+\xi^2} = \mathrm{A}_{\mathrm{s}} (\xi \mathbb{D}),\end{align*} $$

and according to Theorem 1.1, f is a spherical isometry. On the contrary, if f is a spherical isometry, then

![]() $\mathrm {A}_{\mathrm {s}} (f(r \mathbb {D})) = \mathrm {A}_{\mathrm {s}} (r \mathbb {D}) = \pi r^2/(1+r^2)$

for all

$\mathrm {A}_{\mathrm {s}} (f(r \mathbb {D})) = \mathrm {A}_{\mathrm {s}} (r \mathbb {D}) = \pi r^2/(1+r^2)$

for all

![]() $r \in (0,1)$

. Hence,

$r \in (0,1)$

. Hence,

![]() $\mathcal {A}_{\mathrm {s}}(r)$

is constant and equal to

$\mathcal {A}_{\mathrm {s}}(r)$

is constant and equal to

![]() $1$

. In summary,

$1$

. In summary,

![]() $\mathcal {A}_{\mathrm {s}}(r)$

is a strictly increasing function of

$\mathcal {A}_{\mathrm {s}}(r)$

is a strictly increasing function of

![]() $r \in (0,1)$

, unless f is a spherical isometry in which case

$r \in (0,1)$

, unless f is a spherical isometry in which case

![]() $\mathcal {A}_{\mathrm {s}}(r) \equiv 1$

.

$\mathcal {A}_{\mathrm {s}}(r) \equiv 1$

.

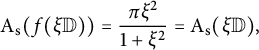

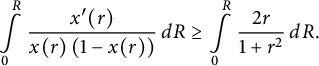

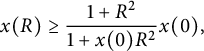

Proof of Corollary 1.2

If

![]() $f \in \operatorname {\mathrm {Rot}}(\widehat {\mathbb {C}})$

, then there is nothing to prove in view of Corollary 1.1. Suppose that

$f \in \operatorname {\mathrm {Rot}}(\widehat {\mathbb {C}})$

, then there is nothing to prove in view of Corollary 1.1. Suppose that

![]() $f:\mathbb {D} \to \widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

is not a spherical isometry. As we see from (5.2), the function

$f:\mathbb {D} \to \widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

is not a spherical isometry. As we see from (5.2), the function

![]() $x(r):= \mathcal {A}_{\mathrm {s}} (r)$

satisfies the differential inequality

$x(r):= \mathcal {A}_{\mathrm {s}} (r)$

satisfies the differential inequality

Since we assume

![]() $f \not \in \operatorname {\mathrm {Rot}}(\widehat {\mathbb {C}})$

, we have

$f \not \in \operatorname {\mathrm {Rot}}(\widehat {\mathbb {C}})$

, we have

![]() $x(r)<1$

for any

$x(r)<1$

for any

![]() $0 \le r<1$

by Theorem 1.2, and hence

$0 \le r<1$

by Theorem 1.2, and hence

$$ \begin{align*}\int \limits_0^{R} \frac{x^{\prime}(r)}{x(r) \left(1-x(r)\right)} \, dR \geq \int \limits_0^{R} \frac{2r}{1+r^2} \, dR .\end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*}\int \limits_0^{R} \frac{x^{\prime}(r)}{x(r) \left(1-x(r)\right)} \, dR \geq \int \limits_0^{R} \frac{2r}{1+r^2} \, dR .\end{align*} $$

By elementary integration and reorganization of terms, we are led to

$$ \begin{align*}x(R) \geq \frac{1+R^2}{1+x(0) R^2} x(0),\,\end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*}x(R) \geq \frac{1+R^2}{1+x(0) R^2} x(0),\,\end{align*} $$

for every

![]() $R \in (0,1)$

. However,

$R \in (0,1)$

. However,

![]() $x(0) = \lim \limits _{r \to 0} \mathcal {A}_{\mathrm {s}}(r)= f^{\sharp }(0)^2$

, and thus, replacing R by r,

$x(0) = \lim \limits _{r \to 0} \mathcal {A}_{\mathrm {s}}(r)= f^{\sharp }(0)^2$

, and thus, replacing R by r,

$$ \begin{align*}\mathcal{A}_{\mathrm{s}}(r) \geq \frac{1+r^2 }{1+r^2 f^{\sharp }(0)^2} f^{\sharp }(0)^2 ,\end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*}\mathcal{A}_{\mathrm{s}}(r) \geq \frac{1+r^2 }{1+r^2 f^{\sharp }(0)^2} f^{\sharp }(0)^2 ,\end{align*} $$

which is equivalent to

$$ \begin{align*}\mathrm{A}_{\mathrm{s}} (f(r \mathbb{D})) \geq \frac{\pi r^2}{1+r^2 f^{\sharp }(0)^2} f^{\sharp }(0)^2.\end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*}\mathrm{A}_{\mathrm{s}} (f(r \mathbb{D})) \geq \frac{\pi r^2}{1+r^2 f^{\sharp }(0)^2} f^{\sharp }(0)^2.\end{align*} $$

If f has the form

![]() $f(z)=T(\eta z)$

for some

$f(z)=T(\eta z)$

for some

![]() $T \in \operatorname {\mathrm {Rot}}(\widehat {\mathbb {C}})$

and

$T \in \operatorname {\mathrm {Rot}}(\widehat {\mathbb {C}})$

and

![]() $0<|\eta |\le 1$

, then writing

$0<|\eta |\le 1$

, then writing

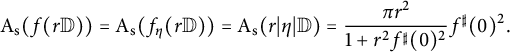

![]() $f_{\eta }(z):=\eta z$

, we have

$f_{\eta }(z):=\eta z$

, we have

![]() $f^{\sharp }(0)=|\eta |$

and

$f^{\sharp }(0)=|\eta |$

and

$$ \begin{align*}\mathrm{A}_{\mathrm{s}} (f(r \mathbb{D}))=\mathrm{A}_{\mathrm{s}} (f_{\eta}(r\mathbb{D}))=\mathrm{A}_{\mathrm{s}} (r|\eta| \mathbb{D})=\frac{\pi r^2}{1+r^2 f^{\sharp }(0)^2} f^{\sharp }(0)^2 .\\[-41pt] \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*}\mathrm{A}_{\mathrm{s}} (f(r \mathbb{D}))=\mathrm{A}_{\mathrm{s}} (f_{\eta}(r\mathbb{D}))=\mathrm{A}_{\mathrm{s}} (r|\eta| \mathbb{D})=\frac{\pi r^2}{1+r^2 f^{\sharp }(0)^2} f^{\sharp }(0)^2 .\\[-41pt] \end{align*} $$

Proof of Theorem 1.4

Suppose that

![]() $f:\mathbb {D} \to \widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

is a spherically convex function. It is then clear that

$f:\mathbb {D} \to \widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

is a spherically convex function. It is then clear that

![]() $\mathrm {A}_{\mathrm {s}} (f(\mathbb {D})) \leq \pi /2$

. According to the isoperimetric inequality (2.10), we have

$\mathrm {A}_{\mathrm {s}} (f(\mathbb {D})) \leq \pi /2$

. According to the isoperimetric inequality (2.10), we have

The expression

![]() $4 \pi \mathrm {A}_{\mathrm {s}} (f(r \mathbb {D})) -4 \mathrm {A}_{\mathrm {s}} (f(r \mathbb {D}))^2$

is increasing with respect to

$4 \pi \mathrm {A}_{\mathrm {s}} (f(r \mathbb {D})) -4 \mathrm {A}_{\mathrm {s}} (f(r \mathbb {D}))^2$

is increasing with respect to

![]() $\mathrm {A}_{\mathrm {s}} (f(r \mathbb {D}))$

on the interval

$\mathrm {A}_{\mathrm {s}} (f(r \mathbb {D}))$

on the interval

![]() $(0,\pi /2)$

, and we obtain from Corollary 1.1 that

$(0,\pi /2)$

, and we obtain from Corollary 1.1 that

$$ \begin{align*} \mathrm{L}_{\mathrm{s}} (f(r \mathbb{T}))^2 \ge \frac{4 \pi^2 r^2}{1+r^2 f^{\sharp }(0)^2} f^{\sharp }(0)^2 \left(1 - \frac{r^2}{1+r^2 f^{\sharp }(0)^2 } f^{\sharp}(0)^2 \right) = \frac{4 \pi^2 r^2 }{(1+r^2 f^{\sharp }(0)^2)^2} f^{\sharp}(0)^2 \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} \mathrm{L}_{\mathrm{s}} (f(r \mathbb{T}))^2 \ge \frac{4 \pi^2 r^2}{1+r^2 f^{\sharp }(0)^2} f^{\sharp }(0)^2 \left(1 - \frac{r^2}{1+r^2 f^{\sharp }(0)^2 } f^{\sharp}(0)^2 \right) = \frac{4 \pi^2 r^2 }{(1+r^2 f^{\sharp }(0)^2)^2} f^{\sharp}(0)^2 \end{align*} $$

for all

![]() $r \in (0,1)$

. The proof of the equality statement is identical to the corresponding proof for Corollary 1.2 and will be omitted.

$r \in (0,1)$

. The proof of the equality statement is identical to the corresponding proof for Corollary 1.2 and will be omitted.

Remark 5.1 The same proof as for Theorem 1.4 but using Theorem 1.1 instead of Corollary 1.1 produces the inequality

with equality for some

![]() $0<r<1$

if and only if f is a spherical isometry. Since

$0<r<1$

if and only if f is a spherical isometry. Since

![]() $f^{\sharp }(0) \le 1$

with equality if and only if

$f^{\sharp }(0) \le 1$

with equality if and only if

![]() $f \in \operatorname {\mathrm {Rot}}(\widehat {\mathbb {C}})$

, the estimate (5.3) is slightly more precise than Theorem 1.3.

$f \in \operatorname {\mathrm {Rot}}(\widehat {\mathbb {C}})$

, the estimate (5.3) is slightly more precise than Theorem 1.3.

6 Monotonicity for length and total curvature

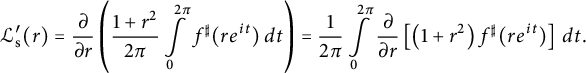

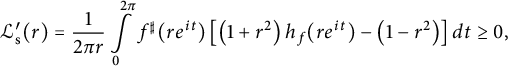

Proof of Theorem 1.5

Let

![]() $f :\mathbb {D} \to \widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

be a centrally normalized spherically convex function. Then

$f :\mathbb {D} \to \widehat {\mathbb {C}}$

be a centrally normalized spherically convex function. Then

$$ \begin{align*}\mathcal{L}_{\mathrm{s}}^{\prime}(r) = \frac{\partial }{\partial r} \left( \frac{1+r^2}{2 \pi} \int\limits_0^{2 \pi} f^{\sharp} (r e^{it}) \, dt \right) = \frac{1}{2\pi} \int\limits_0^{2 \pi} \frac{\partial }{\partial r} \left[ \left(1+r^2\right) f^{\sharp} (r e^{it}) \right] \, dt .\end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*}\mathcal{L}_{\mathrm{s}}^{\prime}(r) = \frac{\partial }{\partial r} \left( \frac{1+r^2}{2 \pi} \int\limits_0^{2 \pi} f^{\sharp} (r e^{it}) \, dt \right) = \frac{1}{2\pi} \int\limits_0^{2 \pi} \frac{\partial }{\partial r} \left[ \left(1+r^2\right) f^{\sharp} (r e^{it}) \right] \, dt .\end{align*} $$

Now, it is easy to see (cf. also [Reference Mejía and Pommerenke16, p. 169]) that

As a result,

$$ \begin{align} \mathcal{L}_{\mathrm{s}}^{\prime}(r)= \frac{1}{2\pi r } \int\limits_0^{2 \pi} f^{\sharp}(re^{it}) \left[\left(1+r^2\right) h_f(r e^{it}) -\left(1-r^2\right) \right] dt \geq 0, \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \mathcal{L}_{\mathrm{s}}^{\prime}(r)= \frac{1}{2\pi r } \int\limits_0^{2 \pi} f^{\sharp}(re^{it}) \left[\left(1+r^2\right) h_f(r e^{it}) -\left(1-r^2\right) \right] dt \geq 0, \end{align} $$

in view of (2.1) with equality if and only if f is a spherical isometry, in which case

![]() $f^{\sharp } (z) = 1/ (1+|z|^2)$

and

$f^{\sharp } (z) = 1/ (1+|z|^2)$

and

![]() $\mathrm {L}_{\mathrm {s}} (f(r \mathbb {T})) = \mathrm {L}_{\mathrm {s}} (r \mathbb {T})$

, so

$\mathrm {L}_{\mathrm {s}} (f(r \mathbb {T})) = \mathrm {L}_{\mathrm {s}} (r \mathbb {T})$

, so

![]() $\mathcal {L}_{\mathrm {s}}(r) \equiv 1$

.

$\mathcal {L}_{\mathrm {s}}(r) \equiv 1$

.

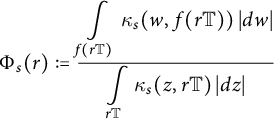

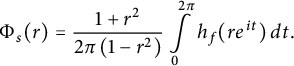

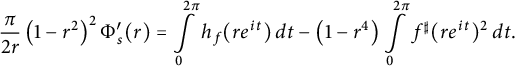

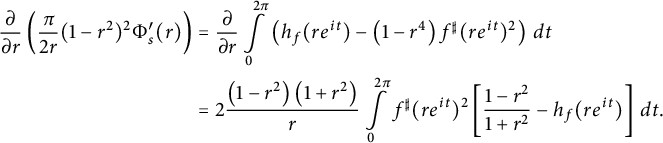

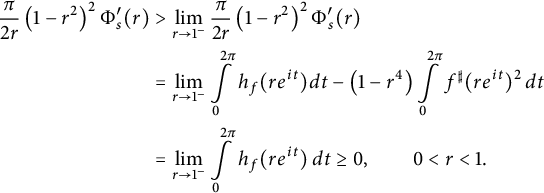

Proof of Theorem 1.6

Let

![]() $f: \mathbb {D} \to \widehat {\mathbb {C}} $

be a spherically convex function which is centrally normalized. Following the calculations in (2.5) and (2.6), the ratio of total curvature of

$f: \mathbb {D} \to \widehat {\mathbb {C}} $

be a spherically convex function which is centrally normalized. Following the calculations in (2.5) and (2.6), the ratio of total curvature of

![]() $f (r \mathbb {T})$

to the total curvature of

$f (r \mathbb {T})$

to the total curvature of

![]() $r \mathbb {T}$

is defined as

$r \mathbb {T}$

is defined as

$$ \begin{align*}\Phi_s(r) = \frac{1+r^2}{2 \pi \left(1-r^2\right)} \int\limits_0^{2 \pi} h_f(r e^{it}) \, dt.\end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*}\Phi_s(r) = \frac{1+r^2}{2 \pi \left(1-r^2\right)} \int\limits_0^{2 \pi} h_f(r e^{it}) \, dt.\end{align*} $$

If f is a spherical isometry, then clearly

![]() $\Phi _s(r) \equiv 1$

, so we assume from now on that f is not a rotation. Taking the derivative of

$\Phi _s(r) \equiv 1$

, so we assume from now on that f is not a rotation. Taking the derivative of

![]() $\Phi _s$

and using (3.4), we deduce

$\Phi _s$

and using (3.4), we deduce

$$ \begin{align*}\frac{\pi}{2r} \left(1-r^2\right)^2 \Phi_s^{\prime}(r)= \int\limits_0^{2 \pi} h_f(r e^{it}) \, dt - \left(1-r^4\right) \int\limits_0^{2 \pi} f^{\sharp}(r e^{it})^2 \, dt.\end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*}\frac{\pi}{2r} \left(1-r^2\right)^2 \Phi_s^{\prime}(r)= \int\limits_0^{2 \pi} h_f(r e^{it}) \, dt - \left(1-r^4\right) \int\limits_0^{2 \pi} f^{\sharp}(r e^{it})^2 \, dt.\end{align*} $$

Note that from (3.4) and

we find by a straightforward computation

$$ \begin{align*} \frac{\partial }{\partial r} \left( \frac{\pi}{2r} (1-r^2)^2 \Phi_s^{\prime}(r) \right) &= \frac{\partial }{\partial r} \int\limits_0^{2 \pi} \left(h_f(r e^{it}) - \left(1-r^4\right) f^{\sharp}(r e^{it})^2 \right) \, dt\\ &= 2 \frac{\left(1-r^2\right)\left(1+r^2\right)}{r}\int\limits_0^{2\pi} f^{\sharp}(re^{it})^2 \left[ \frac{1-r^2}{1+r^2} - h_f(r e^{it}) \right] \, dt. \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} \frac{\partial }{\partial r} \left( \frac{\pi}{2r} (1-r^2)^2 \Phi_s^{\prime}(r) \right) &= \frac{\partial }{\partial r} \int\limits_0^{2 \pi} \left(h_f(r e^{it}) - \left(1-r^4\right) f^{\sharp}(r e^{it})^2 \right) \, dt\\ &= 2 \frac{\left(1-r^2\right)\left(1+r^2\right)}{r}\int\limits_0^{2\pi} f^{\sharp}(re^{it})^2 \left[ \frac{1-r^2}{1+r^2} - h_f(r e^{it}) \right] \, dt. \end{align*} $$

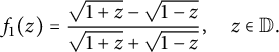

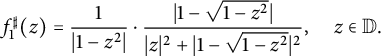

Since f is not a spherical isometry, we deduce from (2.1) that