Introduction

Dementia as defined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders–IV–Text Revision (DSM–IV–TR) is an acquired condition marked by impairments in memory and at least one other cognitive domain that are severe enough to cause significant limitations in social and/or occupational functioning and are not accounted for by a delirium or another Axis I disorder. 1 The DSM–5 renames dementia as major neurocognitive disorder. 2 For diagnosis there must be evidence of significant decline in at least one cognitive domain that is severe enough to interfere with independence in everyday activities. 2 Compared to earlier versions of the DSM, memory loss and impairments in multiple cognitive domains are no longer required features. 2 The various causes of dementia are categorized by their neuropathology, clinical features and/or presumed aetiology. The commoner ones encountered in middle-aged and older individuals are Alzheimer’s disease, vascular, Lewy body and frontotemporal dementia. They occur either as the sole cause of dementia (i.e., “pure” disease) or as combinations of two or more brain pathologies.

In addition to its significant personal toll, dementia is a major contributor to healthcare costs.Reference Wimo, Jonsson, Bond, Prince and Winblad 3 A 2013 report estimated that the annual cost of dementia in the United States was $157–215 billion US.Reference Hurd, Martorell, Delavande, Mullen and Langa 4 The total economic burden of dementia in Canada in 2008 was estimated to be $15 billion dollars. 5 The World Health Organization recognized dementia as a public health priority in 2012. 6 Age is the most important risk factor for dementia, with prevalence doubling every 5 years after 65 (from approximately 2-3% in those 65-69 to 30%+ among individuals over 80).Reference Li, Yan, Li, Chen, Zhang and Liu 7 - Reference Hendrie 12 It might also be more common among women, though the literature is inconsistent on this point.Reference Hendrie 12 , Reference Morris 13 High prevalence estimates are found in long-term care institutions,Reference Matthews and Dening 14 with the majority of those in these settings with moderate to severe dementia.Reference Fratiglioni, Forsell, Aguero Torres and Winblad 15 With societal aging, the burden of this condition will increase over the coming years. It is anticipated that the number suffering from dementia worldwide will double by 2030 and triple by 2050. 6

Whether the incidence and/or prevalence of dementia are changing over time is a key question about the epidemiology of this condition. Recent studies suggest that the age-adjusted incidence and/or prevalence of dementia in older populations could be changing over time but not in a consistent pattern, with estimates decreasing in high-income countries but increasing in middle-income ones. As an example of the former, investigators using data from the Rotterdam Study reported a nonsignificant decline in age-adjusted incidence rates between 1990 and 2010 among those 65+ (incidence rate ratio 0.75, CI95%: 0.56-1.02), possibly on the basis of better control of vascular risk factors. In parallel with an increase in the use of antithrombotics and lipid-lowering drugs over time, brain MRIs showed fewer lacunar infarcts.Reference Schrijvers, Verhaaren, Koudstaal, Hofman, Ikram and Breteler 16 It is plausible that improved cardiovascular risk management would be associated with a decreased incidence but stable prevalence (or a prevalence that is decreasing less markedly than incidence) of dementia as populations affected by dementia would live longer. Matthews et al.Reference Matthews, Arthur, Barnes, Bond, Jagger and Robinson 17 of the UK Medical Research Council Cognitive Function and Ageing Study (CFAS) found that the age- and sex-standardized prevalence of dementia among those 65+ years of age in three geographically defined areas of England was 65 per 1000 in 2011. This was significantly lower than the predicted rate based on 1991 data of 83 per 1000. There was a lower response rate in the 2011 study, but sensitivity analyses suggest that the estimates were robust to this. On the other hand, a systematic review of reports on the epidemiology of dementia in China found that the prevalence rose from 18 per 1,000 (65-69 years of age) and 421 per 1000 (95-99 years) to 26 per 1000 and 605 per 1000 respectively, between 1990 and 2010.Reference Chan, Wang, Wu, Liu, Theodoratou and Car 18 With societal aging worldwide, the number of individuals with dementia will increase, but there is uncertainty about what the actual number will be.Reference Larson and Langa 19 Aside from the importance of having accurate up-to-date figures for planning services to deal with the needs of those suffering from dementia, a better understanding of whether incidence and/or prevalence is changing would have important scientific and clinical consequences. For one thing, a decline would suggest that future rates are partially modifiable and that effectively dealing with modifiable risk factors might delay the onset if not entirely prevent the development of dementia as we age.

The specific objectives of this report are to: (1) provide estimates of the overall worldwide prevalence and incidence of dementia; (2) examine factors that underlie the heterogeneity of estimates (age, sex, setting [i.e., community, institution, both], diagnostic criteria, location of study [i.e., continent]); and (3) search for evidence of change over time in the prevalence and/or incidence of dementia. This study updates and extends the scope of previous reports on the epidemiology of this condition. 9 - Reference Matthews and Dening 14

Methods

This is one in a series of systematic reviews on the prevalence and incidence of priority neurological conditions funded by the Public Health Agency of Canada as part of the National Population Health Study of Neurological Conditions.Reference Caesar-Chavannes and MacDonald 20

Search Strategy

The systematic review and meta-analysis were conducted according to a predetermined protocol based on the PRISMA statement for systematic reviews and meta-analyses.Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman 21 Study authors with expertise in dementia and disease epidemiology and a research librarian with systematic review expertise developed the search strategy and terms (see Appendix A). The MEDLINE and EMBASE databases were searched from January 1985 to February 2011, with references exported and managed using EndNote X5. 22 The search was updated in July of 2012. Due to the availability of prior systematic reviews covering earlier time periods, only international studies published after 1999 were included in our systematic review. Because of the national focus of this project, Canadian studies published between 1985 and 1999 were also included in order to ensure that the Canadian Study of Health and Aging (a large and impactful national study on the epidemiology of dementia) was captured. 9 Articles had to be published in either English or French. The reference lists of included articles were manually searched for additional relevant references.

Study Selection

Two reviewers independently screened the titles and abstracts of all identified references to determine if they appeared to report original data on the prevalence or incidence of dementia. Studies clearly not population-based were excluded at this stage. Two reviewers independently examined the full-text articles identified in the first phase. For inclusion in the systematic review, articles had to meet the following criteria: (1) original research; (2) population-based; and (3) reported an incidence and/or prevalence estimate of dementia. Reviewers fluent in the language of the article examined the paper. Disagreements pertaining to the inclusion of articles were resolved by consensus and, if not reached, by involvement of a third study author.

Data Extraction and Study Quality

Two reviewers independently extracted and reached agreement on data from included articles using a standard data collection form. When multiple articles reported data from the same study population, the reviewers made a judgment as to the most comprehensive and accurate data available, which was then used in analyses. In cases where the studies reported on different timeframes or subgroups (e.g., by sex or age), all data were included. Demographic data recorded included age, sex, study setting (i.e., community, institution, both), and geographic location of study (i.e., continent, country). As not all studies reported on the mean or median age of participants, the youngest age of participants included in a study was employed in our analyses of age. The definitions/diagnostic criteria used for determining the presence of dementia were noted. Incidence and prevalence estimates of dementia from each study were recorded, along with any stratification by age, sex or year of data collection. The quality of the included studies was evaluated using an assessment toolReference Boyle 23 , Reference Loney, Chambers, Bennett, Roberts and Strafford 24 (Appendix B) that assessed such factors as sample representativeness, methods used to determine the presence of dementia, and statistical methods. Each study was given a quality score that ranged from 0 (lowest) to 8 (highest). ANOVA testing was done to determine if study quality varied by location of study (i.e., continent).

Data Synthesis and Analysis

The significance of the impact of age, sex, setting, diagnostic criteria, continent and year of data collection (i.e., when the study was done) on incidence and prevalence estimates was assessed using meta-regression. Age was examined using the youngest age of participants in the study as a continuous variable. Sex, setting, diagnostic criteria and location (i.e., continent) were examined as categorical variables. Changes over time were examined in three separate sensitivity analyses using study start, midpoint and end-years of data collection. All pooled estimates provided are restricted to studies reporting on people aged 60+, 65+ or 70+ to mitigate the potential confounding effects of age. Estimates were also stratified by study setting to limit potential confounding by disease severity. Finally, all estimates reporting on a period (e.g., period prevalence) were converted to annual estimates (e.g., annual prevalence) without restricting time-years.

To be eligible for inclusion in the meta-analysis, studies had to provide either the estimate with 95% confidence intervals (CI95%), or the number of dementia cases along with the sample size, so the prevalence or incidence estimates could be calculated. Additionally, a subgroup was only included in the subgroup analysis if more than one study was available for that subgroup.

To assess for significant between-study heterogeneity, the Cochrane Q statistic was calculated and I 2 was used to quantify the magnitude of between-study heterogeneity. All the pooled estimates and 95% confidence intervals were calculated using a random-effects model. Publication bias was investigated visually using funnel plots and statistically using Begg’sReference Begg and Mazumdar 25 and Egger’sReference Egger and Smith 26 tests.

All statistical analyses were carried out with R version 2.14. 27 The meta package was employed to produce the pooled estimates, forest plots and publication bias assessment.Reference Schwarzer 28 The metafor package was used to conduct the meta-regression using restricted maximum likelihood estimation.Reference Viechtbauer 29 A p value <0.05 was deemed to be statistically significant.

Results

Identification and Description of Studies

The search strategy yielded a total of 16,066 citations, including duplicates (8,743 from MEDLINE and 7,323 from EMBASE). A total of 707 articles were selected for full-text review (Figure 1), of which 547 were excluded (i.e., 230 were international studies published before 2000, 164 did not report an incidence or prevalence of dementia, 114 were not population-based, while 39 provided no original data). An additional four articles were identified by the updated search, while manual reference searching of included papers led to an additional 12 articles, though these papers did not report estimates of overall dementia, but rather only reported on dementia subtypes. Thus, a total of 160 studies were retained, the characteristics of which are shown in Tables 1–3. Twenty studies were not eligible for meta-analysis because they reported duplicate data or did not provide the information necessary to calculate an estimate. A total of 67 studies met the eligibility criteria (described earlier) for inclusion in the meta-analysis of those aged 60+, 65+ or 70+ years.

Figure 1 Study flow diagram.

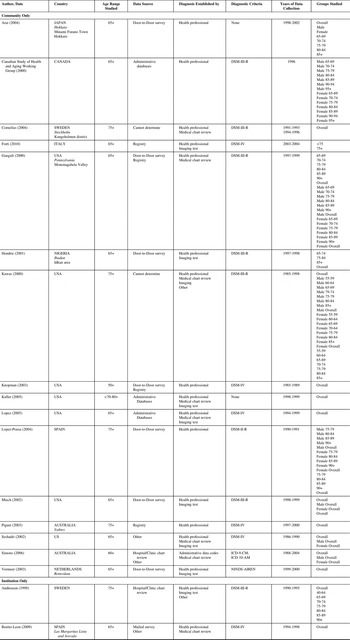

Table 1 Studies Reporting on the Prevalence of Dementia

Table 2 Studies Reporting on the Incidence Rate of Dementia

Table 3 Studies Reporting on the Incidence Proportion of Dementia

Of the 160 total studies, 111 reported on prevalence, 9 , Reference Ebly, Parhad, Hogan and Fung 11 , Reference Matthews and Dening 14 , Reference Aguero Torres, von Strauss, Viitanen, Winblad and Fratiglioni 30 - Reference Zhou, Wu, Qi, Fan, Sun and Como 137 44 on incidence,Reference Corrada, Brookmeyer, Paganini-Hill, Berlau and Kawas 8 , 10 , Reference Andreasen, Blennow, Sjodin, Winblad and Svardsudd 138 - Reference Waite, Broe, Grayson and Creasey 179 and 5 on both.Reference Li, Yan, Li, Chen, Zhang and Liu 7 , Reference Lopez, Kuller, Fitzpatrick, Ives, Becker and Beauchamp 180 - Reference Zuliani, Cavalieri, Galvani, Volpato, Cherubini and Bandinelli 183 Sixty-three originated from Europe, 45 Asia, 43 North America, 7 South America, 5 Australia and 4 Africa (seven studies reported on data from more than one continent).

Prevalence of Dementia

Sixty-six articles reported on the point prevalence of dementia,Reference Li, Yan, Li, Chen, Zhang and Liu 7 , 9 , Reference Anttila, Helkala, Kivipelto, Hallikainen, Alhainen and Heinonen 32 , Reference Anttila, Helkala, Viitanen, Kåreholt, Fratiglioni and Winblad 33 , Reference Benedetti, Salviati, Filipponi, Manfredi, De Togni and Gomez Lira 36 , Reference Bermejo-Pareja, Benito-Leon, Vega, Olazarán, de Toledo and Díaz-Guzmán 38 , Reference Borroni, Alberici, Grassi, Rozzini, Turla and Zanetti 40 - Reference Corrada, Brookmeyer, Berlau, Paganini-Hill and Kawas 45 , Reference Dahl, Berg and Nilsson 47 , Reference de Jesus Llibre, Fernandez, Marcheco, Contreras, López and Otero 50 - Reference de Silva, Gunatilake and Smith 52 , Reference Di Carlo, Baldereschi, Amaducci, Maggi, Origoletto and Scarlato 54 - Reference Fujishima and Kiyohara 57 , Reference Graham, Rockwood, Beattie, Eastwood, Gauthier and Tuokko 64 , Reference Gurvit, Emre, Tinaz, Bilgic, Hanagasi and Sahin 67 - Reference Harvey, Skelton-Robinson and Rossor 69 , Reference Herrera, Caramelli, Silveira and Nitrini 71 , Reference Ikeda, Hokoishi, Maki, Nebu, Tachibana and Komori 73 - Reference Jacob, Kumar, Gayathri, Abraham and Prince 75 , Reference Jitapunkul, Chansirikanjana and Thamarpirat 77 - Reference Kahana, Galper, Zilber and Korczyn 80 , Reference Kivipelto, Helkala, Laakso, Hänninen, Hallikainen and Alhainen 82 , Reference Kivipelto, Helkala, Laakso, Laakso, Hallikainen and Alhainen 83 , Reference Livingston, Leavey, Kitchen, Manela, Sembhi and Katona 88 - Reference Llibre Rodriguez, Ferri, Acosta, Guerra, Huang and Jacob 90 , Reference Mathuranath, Cherian, Mathew, Kumar, George and Alexander 97 , Reference Meguro, Ishii, Yamaguchi, Ishizaki, Shimada and Sato 98 , Reference Nabalamba and Patten 101 - Reference Nunes, Silva, Cruz, Roriz, Pais and Silva 103 , Reference Plassman, Langa, Fisher, Heeringa, Weir and Ofstedal 105 - Reference Riedel-Heller, Busse, Aurich, Matschinger and Angermeyer 109 , Reference Rosenblatt, Samus, Steele, Baker, Harper and Brandt 112 - Reference Sanderson, Benjamin, Lane, Cornman and Davis 115 , Reference Sekita, Ninomiya, Tanizaki, Doi, Hata and Yonemoto 117 , Reference Shaji, Bose and Verghese 120 , Reference Silver, Jilinskaia and Perls 121 , Reference Spada, Stella, Calabrese, Bosco, Anello and Guéant-Rodriguez 123 - Reference Suh, Kim and Cho 125 , Reference Vas, Pinto, Panikker, Noronha, Deshpande and Kulkarni 127 - Reference Wancata, Borjesson-Hanson, Ostling, Sjogren and Skoog 131 , Reference Wertman, Brodsky, King, Bentur and Chekhmir 133 , Reference Yamada, Hattori, Miura, Tanabe and Yamori 135 , Reference Zhou, Wu, Qi, Fan, Sun and Como 137 , Reference Meguro, Ishii, Kasuya, Akanuma, Meguro and Kasai 181 with 29 eligible for inclusion (i.e., provided an estimate with 95% confidence intervals, etc.) in the meta-analysis of those including populations aged 60+, 65+ or 70+ years. 9 , Reference Anttila, Helkala, Kivipelto, Hallikainen, Alhainen and Heinonen 32 , Reference Anttila, Helkala, Viitanen, Kåreholt, Fratiglioni and Winblad 33 , Reference Bermejo-Pareja, Benito-Leon, Vega, Olazarán, de Toledo and Díaz-Guzmán 38 , Reference Bottino, Azevedo, Tatsch, Hototian, Moscoso and Folquitto 41 - Reference Chen, Chiu, Tang, Chiu, Chang and Su 43 , Reference de Jesus Llibre, Fernandez, Marcheco, Contreras, López and Otero 50 - Reference de Silva, Gunatilake and Smith 52 , Reference Di Carlo, Baldereschi, Amaducci, Maggi, Origoletto and Scarlato 54 , Reference Gurvit, Emre, Tinaz, Bilgic, Hanagasi and Sahin 67 , Reference Herrera, Caramelli, Silveira and Nitrini 71 , Reference Ikeda, Hokoishi, Maki, Nebu, Tachibana and Komori 73 , Reference Jacob, Kumar, Gayathri, Abraham and Prince 75 , Reference Jitapunkul, Kunanusont, Phoolcharoen and Suriyawongpaisal 78 , Reference Kivipelto, Helkala, Laakso, Hänninen, Hallikainen and Alhainen 82 , Reference Llibre Rodriguez, Valhuerdi, Sanchez, Reyna, Guerra and Copeland 89 , Reference Llibre Rodriguez, Ferri, Acosta, Guerra, Huang and Jacob 90 , Reference Meguro, Ishii, Yamaguchi, Ishizaki, Shimada and Sato 98 , Reference Rovio, Kareholt, Helkala, Viitanen, Winblad and Tuomilehto 113 , Reference Shaji, Bose and Verghese 120 , Reference Spada, Stella, Calabrese, Bosco, Anello and Guéant-Rodriguez 123 - Reference Suh, Kim and Cho 125 , Reference Wada-Isoe, Uemura, Suto, Doi, Imamura and Hayashi 129 , Reference Wancata, Borjesson-Hanson, Ostling, Sjogren and Skoog 131 , Reference Yamada, Hattori, Miura, Tanabe and Yamori 135 , Reference Meguro, Ishii, Kasuya, Akanuma, Meguro and Kasai 181

In all studies reporting on the point prevalence of dementia (n=66), the majority of studies used a single data source to identify cases (n=51). These included door-to-door surveys (n=16), registry studies (n=10), other sources (n=10), administrative databases (n=3), mail surveys (n=1) and hospital/clinic reviews (n=1). It was not possible to determine the data source in 10 of these studies. A total of 15 studies used multiple data sources. Half (n=33) of the 66 included studies used a single diagnostic method, including a standardized assessment by a healthcare professional (n=26), administrative data codes (n=2), medical chart review (n=2), other sources (n=2) and self-report of a physician diagnosis (n=1).

The pooled point prevalence of dementia per 1000 in 23 community-setting studies was 48.62 (CI95%: 41.98-56.32), while the pooled point prevalence in combined community and institution settings (n=5) was 57.98 (CI95%: 42.02-80.00) (Figure 2). The point prevalence of dementia within institutions (n=2) was 581.09 (CI95%: 558.48-604.61) per 1000. Among the 29 eligible studies reporting on the point prevalence of dementia, estimates ranged from 8.00 per 1000 in a community-only study from IndiaReference Jacob, Kumar, Gayathri, Abraham and Prince 75 to 592.51 per 1000 in an institutional sample from Taiwan.Reference Chen, Chiu, Tang, Chiu, Chang and Su 43

Figure 2 Pooled point prevalence of dementia.

Fifty articles reported on the period prevalence for dementia,Reference Ebly, Parhad, Hogan and Fung 11 , Reference Matthews and Dening 14 , Reference Aguero Torres, von Strauss, Viitanen, Winblad and Fratiglioni 30 , Reference Andersen-Ranberg, Vasegaard and Jeune 31 , Reference Arslantas, Ozbabalik, Metintas, Ozkan, Kalyoncu and Ozdemir 34 , Reference Banerjee, Mukherjee, Dutt, Shekhar and Hazra 35 , Reference Bennett, Piguet, Grayson, Creasey, Waite and Broe 37 , Reference Borjesson-Hanson, Edin, Gislason and Skoog 39 , Reference Cristina, Nicolosi, Hauser, Leite, Gerosa and Nappi 46 , Reference Das, Biswas, Roy, Bose, Roy and Banerjee 48 , Reference Das, Biswas, Roy, Banerjee, Mukherjee and Raut 49 , Reference Demirovic, Prineas, Loewenstein, Bean, Duara and Sevush 53 , Reference Galasko, Salmon, Gamst, Olichney, Thal and Silbert 58 - Reference Gourie-Devi, Gururaj, Satishchandra and Subbakrishna 63 , Reference Guerchet, M’Belesso, Mouanga, Bandzouzi, Tabo and Houinato 65 , Reference Gureje, Ogunniyi and Kola 66 , Reference Helmer, Peres, Letenneur, Guttiérez-Robledo, Ramaroson and Barberger-Gateau 70 , Reference Ikeda, Fukuhara, Shigenobu, Hokoishi, Maki and Nebu 72 , Reference Jhoo, Kim, Huh, Lee, Park and Lee 76 , Reference Kim, Jeong, Chun and Lee 81 , Reference Landi, Russo, Cesari, Barillaro, Onder and Zamboni 84 - Reference Li, Rhew, Shofer, Kukull, Breitner and Peskind 87 , Reference Lovheim, Karlsson and Gustafson 91 - Reference Martens, Fransoo, Burland, Burchill, Prior and Ekuma 96 , Reference Mehlig, Skoog, Guo, Schütze, Gustafson and Waern 99 , Reference Molero, Pino-Ramirez and Maestre 100 , Reference Perkins, Hui, Ogunniyi, Gureje, Baiyewu and Unverzagt 104 , Reference Riedel-Heller, Schork, Matschinger and Angermeyer 110 , Reference Rockwood, Wentzel, Hachinski, Hogan, MacKnight and McDowell 111 , Reference Scazufca, Menezes, Vallada, Crepaldi, Pastor-Valero and Coutinho 116 , Reference Senanarong, Jamjumrus, Harnphadungkit, Vannasaeng, Udompunthurak and Prayoonwiwat 118 , Reference Senanarong, Poungvarin, Sukhatunga, Prayoonwiwat, Chaisewikul and Petchurai 119 , Reference Sousa, Ferri, Acosta, Albanese, Guerra and Huang 122 , Reference van Exel, de Craen, Gussekloo, Houx, Bootsma-van der Wiel and Macfarlane 126 , Reference Wangtongkum, Sucharitkul, Silprasert and Inthrachak 132 , Reference Xu, Qiu, Gatz, Pedersen, Johansson and Fratiglioni 134 , Reference Zhao, Zhou, Ding, Guo and Hong 136 , Reference Lopez, Kuller, Fitzpatrick, Ives, Becker and Beauchamp 180 , Reference Phung, Waltoft, Kessing, Mortensen and Waldemar 182 , Reference Zuliani, Cavalieri, Galvani, Volpato, Cherubini and Bandinelli 183 with 18 eligible for inclusion (see Methods section) in the meta-analysis.Reference Matthews and Dening 14 , Reference Cristina, Nicolosi, Hauser, Leite, Gerosa and Nappi 46 , Reference Das, Biswas, Roy, Bose, Roy and Banerjee 48 , Reference Galasko, Salmon, Gamst, Olichney, Thal and Silbert 58 - Reference Gavrila, Antunez, Tormo, Carles, García Santos and Parrilla 61 , Reference Gureje, Ogunniyi and Kola 66 , Reference Jhoo, Kim, Huh, Lee, Park and Lee 76 , Reference Kim, Jeong, Chun and Lee 81 , Reference Langa, Plassman, Wallace, Herzog, Heeringa, Ofstedal and Burke 85 - Reference Li, Rhew, Shofer, Kukull, Breitner and Peskind 87 , Reference Magaziner, German, Zimmerman, Hebel, Burton and Gruber-Baldini 93 , Reference Scazufca, Menezes, Vallada, Crepaldi, Pastor-Valero and Coutinho 116 , Reference Sousa, Ferri, Acosta, Albanese, Guerra and Huang 122 , Reference Xu, Qiu, Gatz, Pedersen, Johansson and Fratiglioni 134 , Reference Lopez, Kuller, Fitzpatrick, Ives, Becker and Beauchamp 180 , Reference Zuliani, Cavalieri, Galvani, Volpato, Cherubini and Bandinelli 183

In the 50 studies that reported on the period prevalence of dementia, the majority (n=39) used a single source of the study population, including door-to-door surveys (n=21), registries (n=8), other sources (n=4), administrative databases (n=2) and a census (n=1). It was not possible to determine the data source in three studies. Twenty-six of the 50 included studies used a single methodology to identify cases—the majority used a standardized assessment by a health professional (n=22), followed by administrative data codes (n=3). It was not possible to determine how they identified cases in one study.

In community-only settings (n=14), the pooled annual period prevalence per 1000 was 69.07 (CI95%: 52.36-91.11) compared to 72.66 (CI95%: 42.96-122.91) in combined community and institution samples (n=2) and 533.24 per 1000 within institutions (n=2) (Figure 3). Among individual studies, the annual period prevalence estimates ranged from 7.92 in a community-only sample in IndiaReference Das, Biswas, Roy, Bose, Roy and Banerjee 48 to 593.00 per 1000 in an institutional study from the United Kingdom.Reference Matthews and Dening 14

Figure 3 Pooled period prevalence of dementia.

Incidence of Dementia

Seventeen studies reported on the incidence proportion of dementia, 10 , Reference Andreasen, Blennow, Sjodin, Winblad and Svardsudd 138 - Reference Benito-Leon, Bermejo-Pareja, Vega and Louis 140 , Reference Cornelius, Fastbom, Winblad and Viitanen 142 , Reference Forti, Pisacane, Rietti, Lucicesare, Olivelli and Mariani 146 , Reference Ganguli, Dodge, Chen, Belle and DeKosky 148 , Reference Hendrie, Ogunniyi, Hall, Baiyewu, Unverzagt and Gureje 150 , Reference Kawas, Gray, Brookmeyer, Fozard and Zonderman 151 , Reference Knopman, Rocca, Cha, Edland and Kokmen 155 , Reference Kuller, Lopez, Jagust, Becker, DeKosky and Lyketsos 157 , Reference Lopez, Kuller, Becker, Jagust, DeKosky and Fitzpatrick 159 , Reference Miech, Breitner, Zandi, Khachaturian, Anthony and Mayer 165 , Reference Piguet, Grayson, Creasey, Bennett, Brooks and Waite 167 , Reference Seshadri, Beiser, Selhub, Jacques, Rosenberg and D’Agostino 175 , Reference Simons, Simons, McCallum and Friedlander 176 , Reference Zuliani, Cavalieri, Galvani, Volpato, Cherubini and Bandinelli 183 with 10 eligible for inclusion in the meta-analysis of those aged 60+, 65+ or 70+ years.Reference Arai, Katsumata, Konno and Tamashiro 139 , Reference Benito-Leon, Bermejo-Pareja, Vega and Louis 140 , Reference Ganguli, Dodge, Chen, Belle and DeKosky 148 , Reference Hendrie, Ogunniyi, Hall, Baiyewu, Unverzagt and Gureje 150 , Reference Kuller, Lopez, Jagust, Becker, DeKosky and Lyketsos 157 , Reference Lopez, Kuller, Becker, Jagust, DeKosky and Fitzpatrick 159 , Reference Miech, Breitner, Zandi, Khachaturian, Anthony and Mayer 165 , Reference Seshadri, Beiser, Selhub, Jacques, Rosenberg and D’Agostino 175 , Reference Simons, Simons, McCallum and Friedlander 176 , Reference Zuliani, Cavalieri, Galvani, Volpato, Cherubini and Bandinelli 183 All were from community settings. Of 17 studies reporting on the incidence proportion of dementia, 16 used a single methodology to recruit participants, most frequently door-to-door survey (n=5). Other approaches included administrative databases (n=3), registries (n=2), hospital/clinic chart reviews (n=1) and other methods (n=1). It was not possible to determine the data source in two cases, and one study used another methodology. In order to ascertain cases, most studies (n=11) used multiple sources of data (e.g., healthcare professional diagnosis and imaging test results). Six studies based the case ascertainment purely on a healthcare professional assessment.

A random-effects model found that the overall pooled incidence proportion of dementia per 1000 was 52.85 (CI95%: 33.08-84.42) (Figure 4). Among the included studies, incidence proportion estimates ranged from 8.70 in a Japanese studyReference Arai, Katsumata, Konno and Tamashiro 139 to 142.22 per 1000 in a U.S. one.Reference Kuller, Lopez, Jagust, Becker, DeKosky and Lyketsos 157

Figure 4 Pooled incidence proportion of dementia.

Thirty-two studies reported on the incidence rate of dementia,Reference Li, Yan, Li, Chen, Zhang and Liu 7 , Reference Corrada, Brookmeyer, Paganini-Hill, Berlau and Kawas 8 , Reference Bermejo-Pareja, Benito-Leon, Vega, Medrano and Roman 141 , Reference Di Carlo, Baldereschi, Amaducci, Lepore, Bracco and Maggi 143 - Reference Fitzpatrick, Kuller, Ives, Lopez, Jagust and Breitner 145 , Reference Fuhrer, Dufouil and Dartigues 147 , Reference Garre-Olmo, Genis Batlle, del Mar Fernandez, Marquez Daniel, de Eugenio Huélamo and Casadevall 149 , Reference Knopman, Petersen, Cha, Edland and Rocca 152 - Reference Knopman, Rocca, Cha, Edland and Kokmen 154 , Reference Kukull, Higdon, Bowen, McCormick, Teri and Schellenberg 156 , Reference Larrieu, Letenneur, Helmer, Dartigues and Barberger-Gateau 158 , Reference Lopez-Pousa, Vilalta-Franch, Llinas-Regla, Garre-Olmo and Roman 160 - Reference Mercy, Hodges, Dawson, Barker and Brayne 164 , Reference Nitrini, Caramelli, Herrera, Bahia, Caixeta and Radanovic 166 , Reference Polvikoski, Sulkava, Rastas, Sutela, Niinistö and Notkola 168 - Reference Samieri, Feart, Letenneur, Dartigues, Pérès and Auriacombe 174 , Reference Tyas, Tate, Wooldrage, Manfreda and Strain 177 - Reference Phung, Waltoft, Kessing, Mortensen and Waldemar 182 with nine eligible for inclusion in the meta-analysis.Reference Bermejo-Pareja, Benito-Leon, Vega, Medrano and Roman 141 , Reference Di Carlo, Baldereschi, Amaducci, Lepore, Bracco and Maggi 143 , Reference Fitzpatrick, Kuller, Ives, Lopez, Jagust and Breitner 145 , Reference Kukull, Higdon, Bowen, McCormick, Teri and Schellenberg 156 , Reference Larrieu, Letenneur, Helmer, Dartigues and Barberger-Gateau 158 , Reference Nitrini, Caramelli, Herrera, Bahia, Caixeta and Radanovic 166 , Reference Ravaglia, Forti, Maioli, Martelli, Servadei and Brunetti 170 , Reference Samieri, Feart, Letenneur, Dartigues, Pérès and Auriacombe 174 , Reference Tyas, Tate, Wooldrage, Manfreda and Strain 177 , Reference Vermeer, Prins, den Heijer, Hofman, Koudstaal and Breteler 178 The majority of the 32 studies reporting on the incidence rate of dementia used a single source to identify their population (n=21)—these sources were door-to-door surveys (n=8), registries (n=6), administrative databases (n=3) and other sources in two studies. It was not possible to determine the data source in another two studies. Fifteen of the 32 studies used a single methodology to identify cases, including a standardized assessment by a health professional (n=10), chart review (n=4) and administrative data codes (n=1). The remaining 17 used multiple sources.

In community-only settings, the pooled incidence rate of dementia per 1000 person-years was 17.18 (CI95%: 13.90-21.23). In a single combined community and institution study, the estimated incidence rate was 13.33 per 1000 person-years (CI95%: 11.18-15.89) (there were no institution-only studies) (Figure 5). The incidence rate estimates ranged from 8.11 per 1000 person-years in a community-only study from the NetherlandsReference Vermeer, Prins, den Heijer, Hofman, Koudstaal and Breteler 178 to 37.80 per 1000 person-years in a community-only study from Italy.Reference Ravaglia, Forti, Maioli, Martelli, Servadei and Brunetti 170

Figure 5 Pooled incidence rate of dementia.

Sources of Heterogeneity

In our exploration of sources of heterogeneity, we restricted our analyses to studies reporting on individuals 60+, 65+ or 70+ in order to minimize the potential confounding effects of age. Because of the small number of studies, we could not explore the interaction between the potential sources of heterogeneity.

Age

Using the youngest-aged person in a study to assess this characteristic, a series of meta-regression analyses revealed that increasing age was significantly associated (p<0.001) with a higher prevalence or incidence of dementia.

Sex

Meta-regression showed no statistically significant differences between the sexes on any of our estimates, though estimates were consistently higher in females (p>0.05).

Setting

Point Prevalence. Estimates from institution-only settings were significantly higher than those from community-only and combined community and institution settings (p<0.0001). The difference in point prevalence in combined community and institutional settings (57.98 [CI95%: 42.02-80.00] per 1000) compared to community-only ones (48.62 [CI95%: 41.98-56.32] per 1000) was not statistically significant (p=0.33).

Annual Period Prevalence. No significant difference in pooled estimates of annual period prevalence was found between community-only (70.86 [CI95%: 55.78-90.03] per 1000) and combined community and institution settings (72.66 [CI95%: 42.96-122.91] per 1000). Annual period prevalence was significantly higher in institution-only settings (533.24 [CI95%: 435.25-653.28] per 1000, p<0.0001).

Incidence Proportion and Rate. Estimates for incidence proportion were derived solely from community-only settings. There was an insufficient number of studies from non-community settings to assess incidence rate.

Diagnostic Criteria

Comparisons were restricted to studies done in the same setting (community-only, community and institution, institution-only) and where the specific criteria were utilized by more than one study.

Point Prevalence. In community-only settings, there were only sufficient studies for analysis using either DSM–IV (n=16) or DSM–III–R (n=4) diagnostic criteria. There was no significant difference (p=0.33) in the pooled point prevalence estimates between these two criteria.

DSM–IV (n=3) and DSM–III–R (n=2) were the most commonly used criteria in combined community and institutional settings (and the only criteria eligible for inclusion). There was no significant difference (p=0.30) in pooled point prevalence estimates between them.

Annual Period Prevalence. Community-only studies eligible for this analysis employed either DSM–III–R (n=4) or the DSM–IV (n=11) criteria. There was no significant difference (p=0.49) between their estimates for the annual period prevalence.

Incidence Proportion and Rate. In community-only settings, the most commonly used criteria to determine incidence proportion were the DSM–III–R (n=3) and the DSM–IV (n=4). These pooled estimates of the incidence proportion differed significantly from each other, with estimates higher in DSM–IV studies (p=0.03). The only available study for incidence rate used DSM–III–R criteria.

Region

Point Prevalence. Among community-only studies, there were no significant differences in pooled estimates between Asia (n=12), Europe (n=7), North America (n=4) and South America (n=3). There were no differences between Europe (n=3) and North America (n=2) in the pooled point prevalence of dementia among community and institutional studies. The institution-only estimates from North America (n=1) and Asia (n=1) were very similar.

Annual Period Prevalence. There were estimates from four continents for the annual pooled period prevalence of dementia in community-only studies (Asia [n=6], Europe [n=3], North America [n=4], South America [n=2]). The pooled North American annual estimate (129.81 [CI95%: 104.73-160.91] per 1000) was significantly higher than that of Asia (45.24 [CI95%: 25.91-78.99] per 1000), Europe (47.98 [CI95%: 31.95-72.07] per 1000) and South America (69.63 [CI95%: 53.28-91.00] per 1000).

Incidence Proportion. There were community-only studies from two continents (Europe [n=2], North America [n=5]). The estimates from North America (75.48 [CI95%: 47.37-120.28] per 1000) and Europe (64.75 [28.37-147.79] per 1000) were not significantly different (p=0.75).

Incidence Rate. In community-only studies, there were estimates from two continents (Europe [n=5], North America [n=3]). There were no significant differences (p=0.18) in the estimates among them.

Year of Data Collection

Meta-regression revealed that there were no significant changes over time in the incidence or prevalence of dementia.

Publication Bias

There was no evidence of publication bias with either Begg’s or Egger’s test for point prevalence (p>0.05). Evidence of publication bias was found for the period prevalence on both Begg’s and Egger’s tests where smaller studies of the effect were potentially missing (p<0.0001). For the incidence rate, there was no evidence of publication bias on either the Begg’s (p>0.05) or Egger’s (p>0.05) test. Evidence of publication bias was found for the incidence proportion using the Egger’s (p=0.037) but not the Begg’s (p>0.05) test.

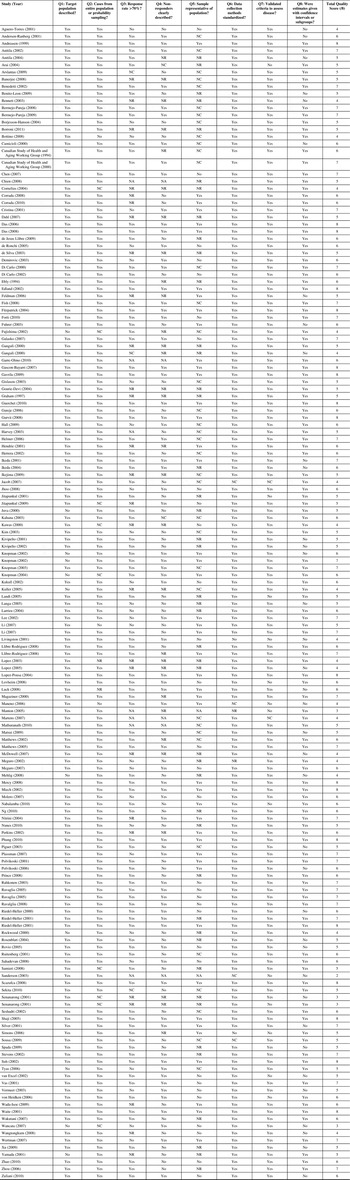

Study Quality

The median study quality score was 6 (range 2-8). ANOVA testing did not reveal any statistical difference in study quality by continent (see Table 4 for details).

Table 4 Quality assessment scores of dementia incidence and prevalence studies

*Note: NR= Not reported; NC= Not clear

Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis of the global incidence and prevalence of dementia provides overall estimates as well as subgroup analyses by age, sex, setting, diagnostic criteria, study location (e.g., continent) and year of data collection. While, as expected, the incidence and prevalence of dementia rose with increasing age, no significant differences in the pooled estimates between men and women were found. There was a non-significant trend for community-only settings to have a lower prevalence than combined community plus institution studies, while the prevalence estimate was significantly higher in institution-only settings. Other than for incidence proportion, there were no significant differences between studies using the DSM–III–R and DSM–IV diagnostic criteria. North American pooled period prevalence and incidence proportion estimates were the highest, while those from Asia were lowest. Estimates of prevalence and incidence did not change over time. Unfortunately, we were not able to show the decline found in some recent studies.Reference Schrijvers, Verhaaren, Koudstaal, Hofman, Ikram and Breteler 16 , Reference Matthews, Arthur, Barnes, Bond, Jagger and Robinson 17 This could have a significant impact on the future burden of this condition. As noted earlier, with societal aging it is anticipated that the number of people with dementia worldwide will double by 2030 and triple by 2050. 6 A decline in prevalence as seen in the CFASReference Matthews, Arthur, Barnes, Bond, Jagger and Robinson 17 would lower estimates of future costs for dealing with dementia in the United States by approximately 40%.Reference Hurd, Martorell and Langa 184

The present study updates the body of literature on the epidemiology of dementia. Compared to other systematic reviews, a broader perspective was generally taken. For example, a recent systematic review on the prevalence of dementia was restricted to persons diagnosed only with DSM–IV and ICD–10 criteria and did not assess heterogeneity by any factor other than geographic region,Reference Prince, Bryce, Albanese, Wimo, Ribeiro and Ferri 185 or focused only on China or Asia and/or did not perform a systematic review or meta-analysis.Reference Catindig, Venketasubramanian, Ikram and Chen 186 - Reference Zhang, Xu, Nie, Lei, Wu and Zhang 188

Erkinjuntti and colleaguesReference Erkinjuntti, Ostbye, Steenhuis and Hachinski 189 examined the effect of different diagnostic criteria on the prevalence of dementia in a large population-based cohort and found widely varying estimates (e.g., 3.1% using the ICD–10 classification system versus 29.1% with DSM–III criteria). More modest differences were found when DSM–III–R and DSM–IV criteria were compared (17.3 and 13.7%, respectively). In this report, we had a limited ability to explore the influence of diagnostic criteria but found evidence that DSM–III–R and DSM–IV criteria produced similar results, other than for incidence proportion.

Prior research has suggested that there might be significant regional differences in the prevalence and incidence of dementia.Reference Prince, Bryce, Albanese, Wimo, Ribeiro and Ferri 185 Unfortunately, there are major limitations in the available data, such as a lack of nationally representative studies in a number of large countries, few reports from some regions of the world (e.g., Sub-Saharan Africa), and the marked heterogeneity seen between countries within a geographic region (i.e., studies carried out in one or two countries cannot be safely generalized to all nations within a specific region). Study quality did not vary by continent in the present analyses. The lowest estimates of period prevalence obtained from Asia are consistent with other recent systematic reviews where the incidence and/or prevalence of other neurodegenerative conditions (i.e., Parkinson’s and Huntington’s disease) have been reported to be lower in Asia.Reference Pringsheim, Jette, Frolkis and Steeves 190 , Reference Pringsheim, Wiltshire, Day, Dykeman, Steeves and Jette 191 A number of factors could account for these differences, including population genetics, exposure to environmental risk factors, differing life expectancy, and variations in case ascertainment due to the amount of stigma associated with certain conditions resulted in underreporting.

The strength of the conclusions that can be drawn from this study is limited by a number of factors. First, the quality of the included studies was variable and at times less than desired (e.g., no reporting of response rates or nonresponder characteristics). Second, significant heterogeneity was present among all estimates of prevalence and incidence. This was likely driven by the differing populations studied and methods used. There was evidence of publication bias for the incidence proportion and period prevalence of dementia, suggesting that there may be unpublished studies reporting differing results. Finally, some studies did not provide the specific data (e.g., proportion with CI95%, numerator and denominator, etc.) necessary to include them in the meta-analyses. To improve the comparability of studies and comprehensiveness of future meta-analyses in this area, an effort should be made to standardize study procedures and reporting.

In conclusion, dementia is a common neurological condition in older individuals. Significant gaps in knowledge about its epidemiology were identified. For example, there are few studies examining the incidence of dementia in low- and middle-income countries, where the disruptive impact of an aging population may be greatest in view of limited resources. Future research should also focus on assessing the impact of utilizing DSM–5 diagnostic criteria for major neurocognitive disorders on estimates, examining differences in rates among subgroups within a larger study population, where appropriate, and further assessing dementia in a variety of settings and geographic regions.

Acknowledgements

We would like thank Ms. Diane Lorenzetti, librarian at the University of Calgary, who guided the development of the search strategy for this systematic review. Our study is part of the National Population Health Study of Neurological Conditions. We acknowledge the membership of the Neurological Health Charities Canada and the Public Health Agency of Canada for their contribution to the success of this initiative. Funding for the study was provided by the Public Health Agency of Canada. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors/researchers and do not necessarily reflect the official views of the Public Health Agency of Canada.

Disclosures

Kirsten Fiest, Jodie Roberts, Colleen Maxwell, Sandra Black, Laura Blaikie, Adrienne Cohen, Lundy Day, Jayna Holroyd-Leduc, Andrew Kirk, Dawn Pearson and Andres Venegas-Torres have nothing to disclose.

Nathalie Jetté has the following disclosures: Public Health Agency of Canada, Principal Investigator, research support; Canada Research Chair, Researcher, research support; Alberta Innovates Health Solutions, Researcher, research support.

David B. Hogan holds the Brenda Strafford Foundation Chair in Geriatric Medicine, though receives no salary support from this.

Statement of Authorship

KMF, NJ, JIR, CJM, TP and DBH contributed to study conception and design. KMF, NJ, JIR, CJM, EES, SEB, LB, AC, LD, JH, AK, DP, AV and DBH contributed to the acquisition of data. KMF conducted the data analysis. KMF, NJ, JIR, CJM, EES and DBH participated in the interpretation of study data. All authors participated in critically revising the manuscript for important intellectual content and gave final approval for the submission of this manuscript and any further submissions of this work.

Supplementary Material

To view the supplementary material that exist for this study (Appendix A and B), please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/cjn.2016.18.