Introduction

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a devastating neurologic disease characterized by progressive loss of limb, respiratory, and bulbar function. The life expectancy from disease onset is approximately 2–5 years. Although there is no cure, an early diagnosis can reduce patient and family anxiety, limit the number of unnecessary diagnostic tests, and maximize the management strategies that exist.Reference Paganoni, Macklin and Lee1

Unfortunately, patients with ALS routinely experience a lag between symptom onset and diagnosis.Reference Hardiman, Van Den Berg and Kiernan2 The established risk factors for these diagnostic delays include age greater than 60 years, sporadic illness (as opposed to familial ALS), limb onset, slowly progressive disease,Reference Paganoni, Macklin and Lee1,Reference Hardiman, Van Den Berg and Kiernan2 delay from primary to secondary services, and in some cases, male gender.Reference Nzwalo, de Abreu, Swash, Pinto and de Carvalho3 Another potential contributor to delay is that ALS is a diagnosis of exclusion, made when other potential mimickers have been ruled out.Reference Cellura, Spataro, Taiello and La Bella4

Nonclinical risk factors, such as urban versus rural living, have previously been queried as potential sources of diagnostic delay.Reference Paganoni, Macklin and Lee1,Reference Aoun, Breen and Edis5 In a recently published Canadian study, mean time of diagnostic delay was significantly different between provinces.Reference Hodgkinson, Lounsberry and Mirian6 Saskatchewan was found to have the longest delay at 27 months, almost double that of some other provinces, but the reasons for this delay were not elucidated. As Saskatchewan has a very large rural and remote population, we sought to explore the possibility of a link between diagnostic delay and distance from tertiary health centers. To our knowledge, this is the first study evaluating the relationship between diagnostic delay in ALS and urban versus rural dwelling.

Patients/Methods

Subjects

This retrospective chart review included all 182 patients with ALS referred to a tertiary ALS clinic in Saskatoon between 2000 and 2016. Eleven charts had incomplete data and were excluded, leaving 171 complete charts for analysis. Patients with other motor neuron disease, such as progressive muscular atrophy and primary lateral sclerosis, were excluded. The patient’s age, sex, place of residence, location from which the referral was made, site of symptom onset, date of symptom onset, date of diagnosis, first appointment in clinic, number of clinic visits, and date of death were recorded. ALS management including utilization of riluzole and communication devices and referral for feeding tube and noninvasive ventilation (NIV) were also charted. Ethics approval was granted by the University of Saskatchewan.

Local Context

The 2016 census indicated that there are just over 1.1 million Saskatchewan residents, in a province approximately 651,000 km2.7 Over 245,000 resided in Saskatoon; 235,000 in Regina, and all other urban centers had populations less than 36,000.8 For purposes of this study, urban residence was defined as residing within 20 km from Saskatoon or Regina. Only Saskatoon and Regina have neurologists in practice, therefore all patients must be referred to these centers for assessment and diagnosis of ALS. During the time period of this study, the diagnosis of ALS was made by a neurologist in Saskatoon or Regina, after which point the patient was referred to a physiatrist at the ALS clinic in Saskatoon for ongoing care. The ALS clinic was not multidisciplinary, but serviced by single physicians who would refer to other specialists and health practitioners according to the patients’ needs.

Statistics

The primary variable was time from symptom onset to ALS diagnosis. The secondary variables included urban and rural differences between ALS clinic access and management. For univariate data presented as proportions, Chi-square statistics were utilized. Kruskal–Wallis ANOVAs were used to compare clinical time metrics. Kaplan–Meier survival curves and log-rank tests were used to assess time of symptom onset and first ALS clinic visit to death. Post hoc analysis of rural patients included simple linear regression modeling for time of symptom onset to diagnosis and distance to the nearest tertiary referral center. p Values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. A total of 78 (45.6%) urban and 93 (54.5%) rural patients were evaluated, 104 (60.8%) male and 67 (39.2%) female. Rural dwellings ranged between 21 and 1118 km from the closest urban center with the majority of rural patients living between 100 and 300 km from the closest urban center. There were 0 patients between 1 and 20 km, 8 patients were within 21–50 km, and 18 patients within 51–100 km from Saskatoon or Regina. Mean age at symptom onset was 64.3 years. Limb onset was the most common presentation (57.3%), followed by bulbar onset (32.7%) with other presentations occurring less commonly. The mean diagnostic delay was 16.6 months.

Table 1: Patient demographics

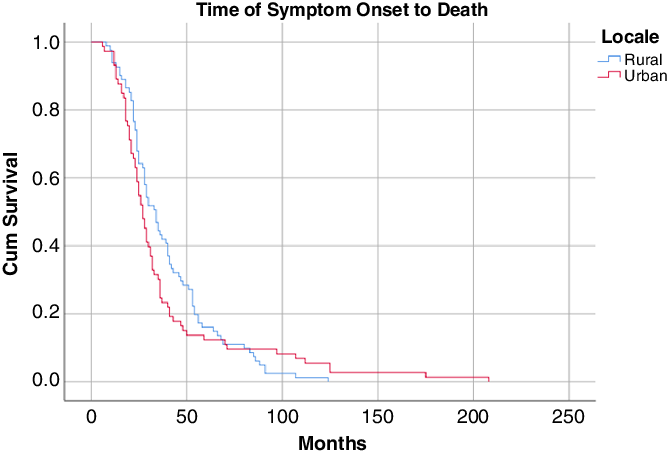

There were no differences between urban and rural patients with time from symptom onset to diagnosis, symptom onset to first clinic visit, and time from diagnosis to clinic visit (Table 2). The were also no survival differences (Figures 1 and 2) from median time of syptom onset [27.0 (95% CI 23.8–30.2) versus 34.0 (95% CI 28.4–39.6) months; log-rank significance 0.44] or first ALS clinic visit to death [14.0 (95% CI 9.9–18.1) versus 18 (95% CI 13.3–22.8) months; log-rank significance 0.39]. For rural patients, linear regression modeling did not find a significant relationship between distance to referral tertiary center and time of ALS diagnosis [F(1,95) = 1.47; p = 0.23; R2 = 0.015].

Table 2: Clinical differences between rural and urban patients with ALS

ALS = amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.

a Median (interquartile range).

b Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA.

Figure 1: Kaplan–Meier survival curve from syptom onset.

Figure 2: Kaplan–Meier survival curve from first ALS clinic visit.

There were no differences between urban and rural dwellers for referral for interventions, including feeding tube, noninvasive ventilation, riluzole usage, and communication devices. Utilization rates for the above interventions also did not differ between the two groups. Both urban and rural patients attended the clinic with equivalent frequency (Table 3). King’s scoring for ALS staging was available for 165 patients (90 rural, 75 urban). Rural patients presented for first clinic visit in the following King’s score categories: 2a = 15 (17%), 2b = 45 (50%), and 3 = 30 (33%). A similar pattern was seen for urban patients: 2a = 13 (17%), 2b = 28 (37%), and 3 = 29 (39%), with a few patients presenting in latter stages of disease: 4a = 3 (4%) and 4b = 2 (3%).

Table 3: ALS management of rural and urban patients

ALS = amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; NIV = noninvasive ventilation.

a Median (interquartile).

b Kruskal–Wallis ANOVA.

Discussion

For our purposes, we have considered patients outside of Regina or Saskatoon to be “rural”. We feel this is justified given the fact that these smaller centers in Saskatchewan would be effectively considered remote with respect to access to neurology, since there are neurologists only in Regina and Saskatoon. In our study, there was no difference in diagnostic delay for rural patients, and despite the large remote population in Saskatchewan, linear regression modeling did not uncover a relationship between the distance from an urban center and diagnostic delay.

While some attention has been paid to the relationship between geospatial factors and incidence, prevalence, and survival in ALS,Reference Rooney, Heverin and Vajda9–Reference Traynor, Codd and Corr16 to our knowledge, the relationship between diagnostic delay in ALS and urban versus rural dwelling is largely unstudied, aside from one paper origininating from the Cantabria region of Northern Spain.Reference Riancho, Lozano-Cuesta and Santurtun13 While not the focus of this study, the median time to diagnosis did differ between groups (4.8 months for urban vs 9.1 months for rural dwellers); however, there are some limitations with interpreting the significance of this finding; while the total number of patients was 53, there is no documentation of the actual number of rural patients included in the study nor is there any information regarding their distance from the tertiary center. Our study, while still small, presents more than three times the number of patients included in the Spanish study. Saskatchewan’s geography and demographics also differs significantly from the region described in this article. Cantabria’s area is 5289 km2 with a reported catchment population of 300,000,Reference Riancho, Lozano-Cuesta and Santurtun13,Reference Lopez-Vega, Calleja and Combarros14 and Saskatchewan’s area is 651,036 km2 with a population of 1.1 million.7 It is difficult to compare such a small and comparatively densely populated region with Saskatchewan’s large territory and sparse population.

Internationally, rural dwelling has been cited as a cause for diagnostic delay in diseases, such as tuberculosis, cancers, congenital hearing loss, and dementia.Reference Ngwira, Dowdy and Khundi17–Reference Williams and Thompson20 Explanations have included travel distance, a higher likelihood that patients would seek alternative/traditional medical care first,Reference Yimer, Bjune and Holm-Hansen19 and lack of education.Reference Kisiangani, Baliddawa and Marinda18 In Saskatchewan, rural patients with dementia experienced diagnostic delay because caregivers had a lack of confidence in their local healthcare center and felt that their privacy may not be maintained.Reference Kisiangani, Baliddawa and Marinda18 Consequently, formal support services were utilized only after the patient could not be cared for adequately at home.Reference Kisiangani, Baliddawa and Marinda18 This is congruent with a Canadian systematic review that reported many rural dwellers with chronic disease in Canada are more hesitant to seek healthcare services until their disease is prohibitive to their ability to work.Reference Riancho, Lozano-Cuesta and Santurtun13 The lack of difference in diagnostic delay for our rural cohort might be explained by the rapid neurologic decline of ALS resulting in significant disability, and the loss of physical independence prompting medical attention.

An additional barrier to receiving adequate specialist care is the distance needed to travel. A study evaluating the usefulness of telehealth for dementia care in Saskatchewan showed that such a system would save patients an average of 426 km per round trip – a distance that may be prohibitive to some patients from attending follow-up care or utilizing a multidisciplinary clinic.Reference Dal Bello-Haas, Cammer, Morgan, Stewart and Kosteniuk21 Compounding this issue, travel in the winter in Canada can be particularly challenging and has been cited as a factor preventing rural dwellers from accessing healthcare.Reference Brundisini, Giacomini, DeJean, Vanstone, Winsor and Smith22 A study of patients and caregivers who attended the recently developed multidisciplinary ALS clinic in Saskatchewan cited travel (including inclement weather) as the only barrier to clinic attendance.Reference Schellenberg and Hansen23 These barriers considered it is somewhat surprising that even the most remote dwellers did not incur a difference in diagnostic delay.

The system of healthcare delivery may be a factor mitigating the rural versus urban discrepancy in diagnostic delay. In 2014, a Spanish study found that the greatest delay occurred between the first consultation with a non-neurologist and the assessment by a neurologist (with referral delay influenced by the patient’s symptoms and age). Patients assessed by a neurologist at the first or second consultation had a significantly shorter diagnostic delay.Reference Nzwalo, de Abreu, Swash, Pinto and de Carvalho3 Furthermore, it has been shown that a shortage of neurologists in rural areas can create diagnostic delay.Reference Sato, Morimoto, Deguchi, Ikeda, Matsuura and Abe24 However, the lack of discrepancy between urban and rural residents in Saskatchewan may be partly due to the existing healthcare system. Primary care physicians are the gatekeepers to secondary and tertiary care available in urban centers; this is consistent for both rural and urban dwellers. Furthermore, both rural and urban patients are placed on waitlists for the same specialists in urban centers; therefore, there is little discrepancy between the waitlist times of urban and rural patients.

Another important consideration is differences in attitude toward formal medical treatment and management. Studies of diagnostic delay in Kenya, Ethiopia, and Morocco show that some rural patients sought alternative, traditional treatments that were better understood by the community.Reference Kisiangani, Baliddawa and Marinda18,Reference Yimer, Bjune and Holm-Hansen19,Reference Maghous, Rais and Ahid25 Although recognizing that the urban/rural discrepancies in these countries may not be applicable to a Saskatchewan population, it might be assumed that rural patients find interventions, such as the insertion of feeding tubes, NIV, riluzole, or use of communication devices less palatable than their urban counterparts. However, our study found that these medical interventions were utilized equally in both rural and urban populations. Of note, both rural and urban patients attended an equal number of clinic visits, which may speak to the engagement of rural patients in the clinic processes. This may also partly explain why geospatial factors in Saskatchewan were inconsequential to patient life span after first symptom onset – a finding consistent with the 2016 study in Ireland that found that distance from dwelling to the ALS multidisciplinary clinic had no bearing on survival.Reference Rooney, Heverin and Vajda9

Lastly, while a recent study on provincial differences in ALS care in Canada found Saskatchewan to have the longest diagnostic delay at 27 months,Reference Hodgkinson, Lounsberry and Mirian6 our study shows Saskatchewan’s diagnostic delay to be an average of 16.5 months – a timeline more consistent with the previously reported provincial averages (mean time to diagnosis 21 months; range 15.1–27.0 months). It has been previously noted that slower progressors may be more likely to be referred to multidisciplinary clinics,Reference Hutchinson, Galvin, Sweeney, Lynch, Murphy and Redmond26,Reference Lee, Annegers and Appel27 and slower progression is also associated with diagnostic delay.Reference Paganoni, Macklin and Lee1,Reference Hardiman, Van Den Berg and Kiernan2 Since the previous Canadian study enrolled a small number from Saskatchewan (n = 22), a recruitment bias is possible whereby the patients attending the clinic were slower progressors thus spending more time in clinic and therefore more likely to be enrolled.

Limitations

Only patients seen at the ALS clinic located in Saskatoon were included in the study; therefore, it is likely that we did not capture all ALS patients in the province and may have missed a discrepancy if one exists. It is known that some patients with ALS were referred to multidisciplinary ALS clinics situated out of province during the era in which these data were collected. Also, it is possible that patients diagnosed at advanced stages of the disease might not wish to travel to a clinic which could be distant from their place of residence. As such, a selection bias exists whereby patients who were unable to tolerate travel would not have attended, and some patients who preferred to travel out of province for multidisciplinary care would not have been included. However, our sample of patients did attend included both urban and rural patients and well represents each demographic.

Due to the long diagnostic delay, it is possible that as the disease limited independent function, some of the patients moved to Saskatoon or Regina in order to receive more intensive care afforded by an urban center prior to their official diagnosis. These patients’ newly acquired urban address would artificially inflate the number of urban dwellers. However, it is unlikely that this would have been a phenomenon widespread enough to affect the results of this study.

A significant limitation is that this is a single-center retrospective study, and further studies would be useful to demonstrate generalizability; further review with a national registry would be valuable. Saskatchewan is a province with a low population, and consequently our sample size is relatively small. However, with its large rural population subject to the same health access as urban dwellers, Saskatchewan offers an ideal population to study the impact of geography on diagnostic delay.

Conclusions

To our knowledge, this is the first study to assess the relationship between diagnostic delay and rural/urban dwelling among ALS patients. While rural residence has been shown to increase diagnostic delay in the case of other diseases, our study found no association between rural location and delay. This finding held for rural patients living in rural settings situated relatively close to urban centers (<100 km) as well as rural dwellers living very remotely from urban centers (>400 km). Furthermore, rural Saskatchewan residents were as equally likely to receive medical intervention as their urban counterparts.

Additional studies of this relationship between rural/urban dwelling and diagnostic delay in ALS are needed in order to demonstrate whether this finding is reproducible.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by a Dean’s Project Award funded by the College of Medicine at the University of Saskatchewan in Saskatoon, Canada.

Disclosures

The authors do not have any relevant disclosures.

Statement of Authorship

KS: Conception of research idea and study design, supervision of literature review, and manuscript writing and editing. GH: Contribution to study design, statistical analysis, and manuscript writing and editing. MA: Data collection, literature review, and manuscript writing.