Introduction

The current First World War (FWW) 1914-1918 centenary is an appropriate time to examine the relationship of two major figures in Canadian history: General Sir Arthur Currie and Wilder Penfield.

Canada, as a part of the British Empire, was automatically drawn into the conflict when war was declared on Germany by Great Britain in August 1914. A dearth of professional soldiers necessitated that the Canadian fighting units would be composed of civilians, like Currie, who had to be rapidly trained. The FWW created the circumstances that allowed the transformation of Currie from an unknown real estate agent to a Canadian icon within 4 years. Currie’s postwar profile led to his appointment as Principal of McGill University and consequently his connection to Penfield and the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI).

Wilder Penfield

Penfield needs little introduction to the neuroscience community. The reader interested in details of his career is referred to Penfield’s biography;Reference Lewis 1 partial autobiography,Reference Penfield 2 and the highly recommended recently published history of the MNI.Reference Feindel and Leblanc 3 Penfield is widely known for his contributions to clinical neuroscience and as the driving force behind the concept and creation of the MNI.Reference Feindel 4 , Reference Feindel 5

Penfield was born in 1891 in Spokane, Washington but later became a Canadian citizen and died in 1976 in Montreal. His undergraduate education was at Princeton and subsequently he studied at Oxford as a Rhodes Scholar.Reference Lewis 1 Penfield obtained his medical degree from Johns Hopkins in 1918 and, as an intern, received neurosurgical training from Harvey Cushing in Boston. Penfield returned to England in 1919 for 2 years of study during which he was exposed to some of the distinguished neuroscience clinicians of the era including Percy Sargent, Gordon Holmes, Kinnier Wilson, and J. Godwin Greenfield.Reference Feindel 4

Penfield arrived in New York in 1921 with an appointment at the Presbyterian Hospital to perform “neurological surgery”.Reference Penfield 2 In 1924 he travelled to Madrid to learn novel histology staining techniques from Pio del Rio-Hortega and returned to New York to establish a neurocytology laboratory that attracted William Cone. Cone became a trusted neurosurgical colleague and part of the “package deal” that eventually brought Penfield and Cone to Montreal.Reference Lewis 1 , Reference Penfield 2

Penfield describes the courtship by McGill University as beginning in 1927 when the McGill Professor of Surgery, Edward Archibald, travelled to New York on a recruiting mission.Reference Penfield 2 Archibald asked Penfield, then 36 years old, to come to Montreal to take over Archibald’s neurosurgical practice which would allow Archibald to concentrate on thoracic surgery. Archibald was looking for a neurosurgeon but Penfield had a larger agenda including the recruitment of Cone, the creation of a neuropathology laboratory and, perhaps, something even grander. Penfield came to Montreal at Archibald’s invitation on 10 January 1928 for a full day of meetings and discussion.Reference Penfield 2 A formal luncheon was held in Penfield’s honour at the Mount Royal Club with the affair presided over by McGill’s Principal, Sir Arthur Currie.

Sir Arthur Currie: Early Life

Penfield is a “household name” within the neuroscience community but Arthur Currie is likely not. A vignette of Currie’s life follows as a segue to the Penfield–Currie relationship.

Little in Currie’s early life could predict the steep ascent of his later career. He was born on 5 December 1875 and raised on a farm in the Adelaide–Strathroy region of southwestern Ontario. He demonstrated early academic promise and was blessed with an outstanding memory. The death of Currie’s father when Arthur was 16 led to financial hardship that precluded him a university education. Currie entered a training school for teachers but inexplicably left a month before his final examinations and travelled to Vancouver Island, British Columbia. He obtained employment as a teacher and married in 1901. However, he abandoned teaching for a more lucrative career in Victoria selling insurance and in 1908 entered the world of real estate.Reference Urquhart Hugh 6

Earlier, in 1897, Currie had joined the non-permanent active militia. Currie entered the militia at the lowest of ranks but rapid advancement was attributed to his enthusiasm, organizational skills, and great attention to detail.Reference Urquhart Hugh 6 The militia activities that began as a pastime culminated with Currie taking command of his regiment in 1909.

With the declaration of war in August 1914 Currie accepted command of an infantry brigade (a military formation of ~4,000 soldiers).Reference Hyatt 7 A mere 6 months later the citizen real estate agent from Victoria was a front line soldier of the at the Second Battle of Ypres in Belgium and participated in a successful defence against the new German terror weapon—chlorine gas.Reference Urquhart Hugh 6 , Reference Hyatt 7

Meteoric describes Currie’s career in the next 4 years. His leadership at Ypres led to promotion in September 1915, at age 40, to command the first Canadian Division (note: a “division” was a military unit consisting of ~18,000 soldiers that included three infantry brigades, 76 field guns, engineers, medical services, 5,600 horses, etc.).Reference Hyatt 7

In late 1916 the four Canadian Divisions (collectively known as a “Corps”) were moved to the Vimy sector under the command of British General Sir Julian Byng. Currie was obsessed with strategies and tactics that would reduce the appalling casualty rates during FWW offensive actions.Reference Dancocks Daniel 8 Currie and Byng became known for implementing many principles that led to the success of the Canadian Corps’ April 1917 capture of Vimy Ridge during which Currie’s first Division performed superbly. The Canadians emerged from Vimy with a reputation as the “shock troops” of the British army.Reference Cook and Shock 9

Currie’s success at Vimy led to a knighthood from King George V in June 1917 and command of the entire Canadian Corps (~100,000 troops)—a role the new lieutenant-general would retain until the end of the war.Reference Dancocks Daniel 8

The Canadian Corps was involved in a series of major military actions from September 1917 to the war’s conclusion in November 1918. Although Currie may be best known in the Canadian consciousness for his role at Vimy Ridge and Passchendaele, Currie felt the zenith of the Canadian Corps’ accomplishments was in the last 4 months of the war. From August to November 1918 (“the last 100 days”) the Canadian Corps was called on repetitively to be at the sharp end of the spear as many senior commanders considered the Canadians to have evolved to become the elite attack force of the entire British Empire. The four Canadian Divisions, in Currie’s words, “met and defeated over 50 German divisions … elements of 17 additional divisions were also encountered and crushed. … No force of equal size ever accomplished so much in a similar space of time during the war”.Reference Dancocks Daniel 8

The Armistice was signed 11 November 1918 but Currie did not return to Canada until August 1919. His reception on return was mixed. The country was weary from the war and ready to move on. Currie, after 5 years abroad, was an exhausted man. Some initial discussion in Ottawa of a cash reward for service, a practice well established in England for its generals, was quietly abandoned. Currie needed a job and was appointed inspector-general of the Canadian forces but fiscal restraints on a war indebted country did not allow for his reform proposals. He continued to be ignored by the politicians of the day with no formal specific words of thanks from the government.Reference Cook 10

An unexpected lifeline came in 1920 when Currie accepted an offer from McGill to become the university’s principal. Currie had reservations about accepting this position because of his lack of qualifications (no diploma or any certificate past high school) but the university was interested in his name, leadership ability, and organizational skills. He was offered an excellent salary and housing that were welcomed by the financially stressed Currie.Reference Urquhart Hugh 6

Currie inherited a university that was long on a tradition of academic excellence but short on finances. He quickly raised $6.2 million dollars that helped to fund a new biology building, a Pathological Institute, a convocation hall, a new wing of the Redpath Library, and a Chair of Medicine.Reference Urquhart Hugh 6

This is the man who presided over Penfield’s lunch ceremonies at the Mount Royal Club in January 1928. Penfield, in his autobiography, specifically mentions Currie as “toastmaster” and clearly enjoyed his experience with the 25 assorted guests: “I had a sense of being at home with men I liked”.Reference Penfield 2

Penfield Recruited and Early Considerations of the MNI

Penfield was fortunate to arrive when he did as the early 1920s were a time of revolutionary change in medical education and medical politics at McGill. The visionary Charles Martin was appointed as the first full-time McGill Dean of Medicine in 1923. Among his many accomplishments, Martin had the leading role in a successful bid to the Rockefeller Foundation (RF) to fund a full-time Professor of Medicine (with implications for clinical teaching and research). Martin also adroitly settled a calamitous “town vs. gown” situation in the Departments of Surgery at the Royal Victoria Hospital (RVH) and McGill that led to the appointment of Edward Archibald as the head of surgery in both institutions. The reorganization of the surgical services substantially improved the local “climate” at the time that Penfield was being recruited. Details of the fractious McGill-RVH politics, Dean Martin’s leadership, and his productive relationship with Principal Currie can be found in Entin et al.Reference Entin, Hanaway and Nimeh 11 Martin and Currie’s negotiating skills ensured that the ownership and control of the MNI was at McGill and not the RVH.Reference Entin, Hanaway and Nimeh 11

Deliberations continued after Penfield’s initial visit to Montreal and he eventually arrived in Montreal in late 1928 as the Professor of Neurosurgery at McGill and Surgeon-in-Charge of Neurosurgery at the RVH.Reference Lewis 1

The novel concept of an institution which housed under one roof neurological clinical care and laboratories for neuroscience was not a prerequisite for Penfield coming to Montreal. However, as early as January 1929 Penfield wrote to Archibald: “The enclosed plan for an Institute for Neurological Investigation may take you somewhat by surprise. The idea and the plans have been slowly taking form in my mind. … It is my hope that the Rockefeller Foundation would be interested in such an undertaking”.Reference Penfield 2

Complex negotiations continued that culminated in April 1932 of a grant of $1,232,000 by the RF to McGill University with 1 million dollars as an endowment for research and the remainder for half the cost of the MNI structure.Reference Penfield 2 Additional funds required for the construction of the building were to be raised locally from private and government sources.

The original site for the MNI was planned for property owned by the RVH but the space was not suitable and it was Currie who convinced the McGill Board of Governors to donate the land on University Avenue where the MNI currently stands. Although Penfield worked closely with the designers on virtually every detail of the unique design of the MNI it was Currie who chose the architectural firm of Ross and MacDonald.Reference Adams and Feindel 12

26 November 1931: Currie Saves the Day

Adams and Feindel were the first (and only recently) to provide documentation and the credit deserved by Currie for his pivotal role in rescuing the entire MNI project from cancellation.Reference Adams and Feindel 12

The RVH Superintendent, William Chenoweth, had major concerns over financial liabilities of the RVH in providing hospital services to the MNI. Chenoweth’s primary responsibility was to the RVH and he felt that money required from the hospital for the proposed MNI would preclude investment in other needed services at the hospital. Further, Chenoweth had doubts about Penfield’s commitment to Montreal as Penfield was entertaining an invitation to relocate to Philadelphia.Reference Adams and Feindel 12 The RVH President Holt shared these concerns and wrote on 19 November 1931 that “it is out of the question for the Royal Victoria Hospital to take on this obligation” (original citation in Adams and FeindelReference Adams and Feindel 12 ).

26 November 1931 was a critical day for the future of the MNI. Chenoweth received a financial update from the architects that disclosed substantially rising costs and Chenoweth called an emergency meeting of the Board of Governors of the RVH with a clear intent to cancel the entire project.Reference Adams and Feindel 12 Importantly, in view of Penfield’s subsequent opinion of Currie, Penfield does not appear to have ever known about this meeting—or at least never acknowledged it. Currie, however, was present and made it clear to the Board that if the MNI project failed to progress Penfield and Cone would leave Montreal. Currie’s extraordinary five-page address in support of Penfield and the MNI project resides in the McGill University Archives. Currie proclaims his unequivocal and unqualified support of Penfield. 13

In reference to Penfield and neurosurgical colleague Cone, Currie said “that there can be no doubt whatever to their importance to McGill University and the Royal Victoria Hospital. … They have both been here three years, and have proven their worth both as personalities and men, diagnosticians, surgeons, and consultants … it would be a tragic loss to have them go”. With specific reference to Penfield, Currie notes “he is one of our greatest drawing cards … has attracted patients from all over the continent … has a prestige which places him in the very first rank of neurological surgeons”. Currie asks the Board of Governors, noting that $75,000 has already be raised: “are we now going to throw this sum into the discard after such a promising start? … Such a failure would destroy the confidence of those private citizens who have so generously supplied the funds which have laid the foundation for the work. … We will place such a black mark on the record of our Medical school that it will take long years to erase it. … If these men now leave Montreal we will not be able again in a generation to start new men upon this road, and our work in Neuro-Surgery will be placed where it was ten or fifteen years ago, that is, in a position of utter mediocrity. It is men, and not buildings, that make a hospital and a medical school”.

(Note: this emergency RVH Board of Governors meeting was held 5 months before the official announcement of the grant from the RF.) Currie continued: “The Rockefeller Director has already declared that Penfield is the only man with whom the Foundation would at present care to associate an important gift for neurosurgery, and if we are correct in our impressions, they are prepared to interest themselves in a very large and important gift to Montreal, if we on our part manifest a sufficient interest”. … “If we show an apathetic attitude now it is doubtful if our future relations with them will be as intimate as heretofore”.

Currie, characteristically, came to the Board prepared. He tells the Board that the next RF Trustees meeting was scheduled to take place in one week and anticipates that a decision to award the grant to McGill will be made. The next meeting after the 3 December 1931 RF Trustees meeting “takes place in May 1932 and by that time Johns Hopkins, Philadelphia, and probably Chicago will make application to the foundation for a neurological institute”. Currie felt that an ambivalent position from Montreal would surely diminish the chance for McGill to obtain the full amount currently in the request. Currie concludes with an impassioned plea for the reputations of the RVH and McGill that “if we lose the opportunity that is now knocking at our door that there will be attached to both institutions a stigma that will long remain … and I beg you to make every effort to retain these men in Montreal”.

Unfortunately, the minutes of the discussion during this momentous meeting, if they exist, cannot be located but clearly Currie convinced the RVH Board of his perspective and rescued the MNI project. Penfield’s biographer—who also appears to have been incognizant of this November 1931 meeting—unfairly characterizes Currie as unsupportive of Penfield and “neither financier nor politician”.Reference Lewis 1

January 1933: Currie and Penfield Showdown

The budget issues of the MNI construction continued and Currie, too, was keeping an eye on costs. On 17 August 1932 Currie wrote a detailed letter to Penfield expressing concerns that the most recent architectural plans had alterations that were not included in the original description to the RF. 14 Currie expresses his concern that the increased cost of the architectural changes would become the responsibility of the University.

Penfield, later, wrote of this era that he could sympathize with Currie and acknowledged Currie’s position that during the FWW he was “no doubt, a great leader of men in such surroundings. Now he was dictatorial, but unsure of himself, immature and boyish at heart. He must protect McGill, he thought, against financial loss”.Reference Penfield 2

An explosive meeting between Currie and Penfield occurred in January 1933. Penfield was summoned by Currie to his office for a meeting that included the MNI building committee. Currie showed Penfield a new set of architectural plans that had the building scaled down by two floors (the laboratories and the animal quarters) that would have severely constrained the research facility that Penfield wanted. Penfield was livid and, writing many years later, recounted the scene.Reference Penfield 2

Currie stated “We must cut the coat to fit the cloth”. Penfield responded that if this were to be the case that the project would have to go on without him but added that if Currie were to change his mind and wanted Penfield’s help that he would participate. However, Penfield’s future participation would only be under the conditions that the neurological institute had to be “perfect in every functional detail”. The always well prepared Currie was then described by Penfield as crashing his enormous fist on the table and exclaiming “Damn it! They told me you would say just that. Well, I’ve made up my mind what I would say in case you did”. Currie then laughed and indicated that they could not continue without Penfield and they would have to trust Penfield’s contention that the institute would be able to pay its own way. Penfield pledged to contribute some research funds, strict budget controls were set up by the architects, one elevator was omitted, and one laboratory was left unfinished.Reference Adams and Feindel 12 Thus, this crisis was settled and the final plans were accepted in June 1933.

6 October 1933: The Cornerstone Ceremony

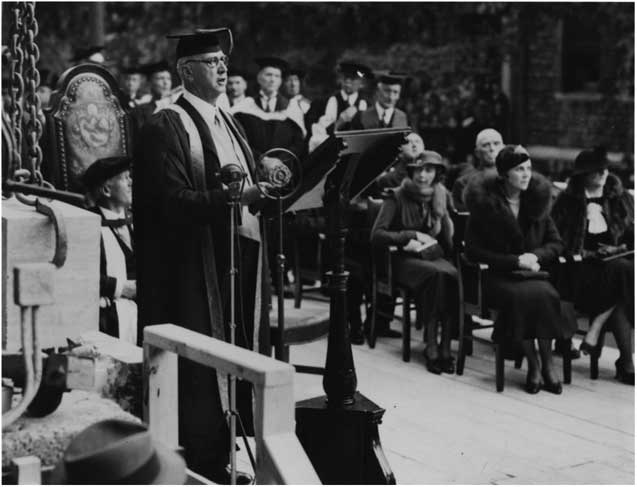

Currie chose to have a major ceremony to mark the laying of the cornerstone of the MNI. The date was set for McGill Founders Day 6 October 1933 and the Governor General of Canada, Lord Bessborough, was invited to lay the cornerstone (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 Currie giving his address at the Cornerstone Laying Ceremony of the MNI 6 October 1933. No photograph has been found showing Currie and Penfield together. Photograph reproduced with permission of the Osler Library, McGill University.

Penfield was churlish about Currie’s plan. In a 20 August 1933 letter to his mother, Penfield wrote that Dean Charles Martin had called Penfield at his summer farm to indicate that “if I wanted to discuss preparations for the cornerstone ceremonies I had better come up as Currie was making all arrangements ... I told him he could do what he liked. I don’t care what they do. Such occasions are just flourish and empty vainglory. … The cornerstone laying is for the builders. The opening will be for us who know its meaning”. 15

Invitations were sent and among the dignitaries present were the Bishop of Montreal, the Quebec premier, the mayor of Montreal, representatives from the RF, prominent Montreal donors, other McGill and RVH officials, and of course Penfield.

The ceremony began at 3 PM. The Governor General arrived and used a ceremonial trowel made specifically for the occasion. 16 Documents were placed in the cornerstone including the university charter, the hospital charter, documents from the RF, and the latest editions of seven Montreal newspapers. 17

Currie gave an address that summarized the 10 years of effort that led to the construction of the MNI and credited Archibald’s successful search for a neurosurgeon and continued: “Upon Dr. Penfield’s arrival, the profession here soon realized the presence of an outstanding expert in this field, and witnessed an astounding change in the character of the work, its obvious importance and benefit, both to patients, to students in training, to practitioners, to medical science and to medical education. … Great success attended all of Dr. Penfield’s work with the result that he is now recognized as one of the very foremost brain surgeons in the world. Patients have come to him from all over this continent, and young research workers have come even from foreign lands to study and work under him”. Currie alluded to the difficulties in achieving the project’s success: “Many times the outlook appeared dreary and even discouraging. … Some were lukewarm who should have been enthusiastic, and some who might have been helpful remained aloof. Fortunately, others have not yet learned to surrender in the face of opposition and difficulties”. 18

One might think that Penfield would have been pleased. Indeed, he sent a short handwritten note to Currie on 14 October: “I want to congratulate you on the perfection of the ceremony of the cornerstone laying. Ceremonies are so rarely exactly what they should be and addresses almost never fit the occasion as yours did. Founder’s Day to me will always bring the memory of your founding of the Institute and my resolve to make it worthwhile. Yours sincerely, Wilder Penfield”. 19 However, Penfield’s congratulatory note was anything but sincere. In a letter to his mother 2 days later Penfield wrote “Currie talked for some time and the Bishop blessed everything and I had a desire to weep and to run away. People congratulated me as though I had done something”. 20

Unfortunately, Currie did not live to see the official opening of the MNI 1 year later.

Death of Currie

On 5 November, just 1 month after the cornerstone ceremony, Currie abruptly collapsed at home and was diagnosed as suffering a midbrain stroke. Currie lingered in hospital until 30 November 1933 when he succumbed just 5 days short of his 58th birthday.Reference Dancocks Daniel 8

Penfield did not attend Currie’s funeral. Letters to Penfield’s mother from 30 November 1933 21 and 3 December 22 indicate that Penfield was on a speaking tour in western Canada before visiting his mother in Los Angeles. His November 30 letter describes receiving a telegram from Cone announcing that one of Penfield’s patients had developed meningitis and Penfield responding to Cone by telephone from Calgary. Penfield mentions to his mother the possibility that, because of the patient’s illness, he may have to return to Montreal but there is no mention of returning for Currie’s funeral. In fact, there is no mention of Currie et al 21 , 22 and Penfield did not return to Montreal.

Although Penfield was noncommittal (at least to his mother) about Currie’s death, the rest of the world was not. Currie’s funeral on 5 December was more elaborate than any state funeral in the history of Canada.Reference Dancocks Daniel 8 The proceedings were broadcast live on radio in Canada. London’s Westminster Abbey was filled to capacity for a memorial service. In Montreal the funeral service at the Anglican cathedral was attended by the Prime Minister and the Governor General. A hearse transported the casket to the McGill campus where the casket was moved to a gun carriage and subsequently escorted by cavalry and hundreds of infantrymen. The route from McGill to the Mount Royal Cemetery Montreal was lined with an estimated 250,000 people and 500 policemen. Words of condolence arrived from King George V, the Canadian, British, French, and Japanese governments. McGill’s Chancellor, Sir Edward Beatty, wrote that the tributes paid to Currie were “unequalled in the history of this country”.Reference Dancocks Daniel 8 No written condolence note from Penfield has been found.

Aftermath

With respect to the MNI, “Penfield’s recognition of Currie’s contribution to the project was muted at best”.Reference Adams and Feindel 12

The official opening of the MNI, 1 year after the cornerstone ceremony, took place 27 September 1934. The opening ceremony was a Penfield production that he clearly savored and included 300 guests who marched up University Street “gowned in robes as splendid as anything in the Middle Ages could have produced”.Reference Penfield 2 Guests included the mayor of Montreal, the McGill Dean of Medicine (Martin), Archibald, Harvey Cushing, Gordon Holmes, and other prominent neurologists and neurosurgeons. Although Sir Arthur’s wife, Lady Currie, received an invitation her attendance is unknown.

Penfield, for the MNI opening, acknowledged Currie and quoted Currie from his cornerstone ceremony address: “Unfortunate men and women, suffering from the most delicate and most misunderstood of all human afflictions, will find this Institute a blessing”. Penfield continued his opening remarks with “A few short weeks after Sir Arthur had uttered these words he was stricken with one of the human afflictions to which he referred, and we stood by his bedside helpless because of what he had justly termed misunderstanding”. 23

This statement is the sole reference to Currie at the MNI opening ceremony.

The passage of time did not soften Penfield’s view of Currie. There is no documentation that Penfield ever wrote another word about Currie until 40 years later. Only weeks before Penfield’s death on 5 April 1976 he was working on the final draft of “No Man Alone”.Reference Penfield 2 Penfield’s personal diary contains many entries pertaining to the “No Man Alone” manuscript. In March 1976 Penfield incorrectly writes in his diary that “Currie died Oct 1933” and follows with the enigmatic entry pertaining to the manuscript 24 :

“I re-wrote Chapter 17 (The Germinal Idea) shortening and telling the adult truth. It is allright. I’ve redone Ch 18 (The Difficult Years of Building) and have put the delaying villain, Sir Arthur Currie in using novelistic techniques”.

It is unclear what Penfield means by “novelistic” and no additional explanation was provided in the last 4 weeks of his life.

Conclusion

Nobody could argue that the vison and drive of Penfield were the key ingredients in bringing his concept of the MNI to fruition. However, Sir Arthur Currie provided the necessary support during critical phases of the planning process that, had this resolve been lacking, may have led to Penfield’s departure from Canada and the MNI never to exist. Penfield’s own writings and his biographer paint Currie as a meddling administrator. It seems untenable that Penfield was oblivious to Currie’s support yet Penfield retained an enduring resentment towards Currie. An examination of primary source documents strongly suggests that Currie was a pragmatic, fiscally responsible, highly supportive executive deserving of credit in the MNI success story.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks Christopher Lyons (Osler Librarian, McGill University) and Lori Podolsky (Acting University Archivist, McGill University Archives) for their incalculable assistance in the retrieval of source documents related to this project and their patience with his inquiries. Also, Susan Rahey (Neurophysiology Program Coordinator, QEII Health Sciences Centre, Halifax, NS) for inspiration for this project.

DISCLOSURES

The author has no disclosures relevant to this manuscript.