No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

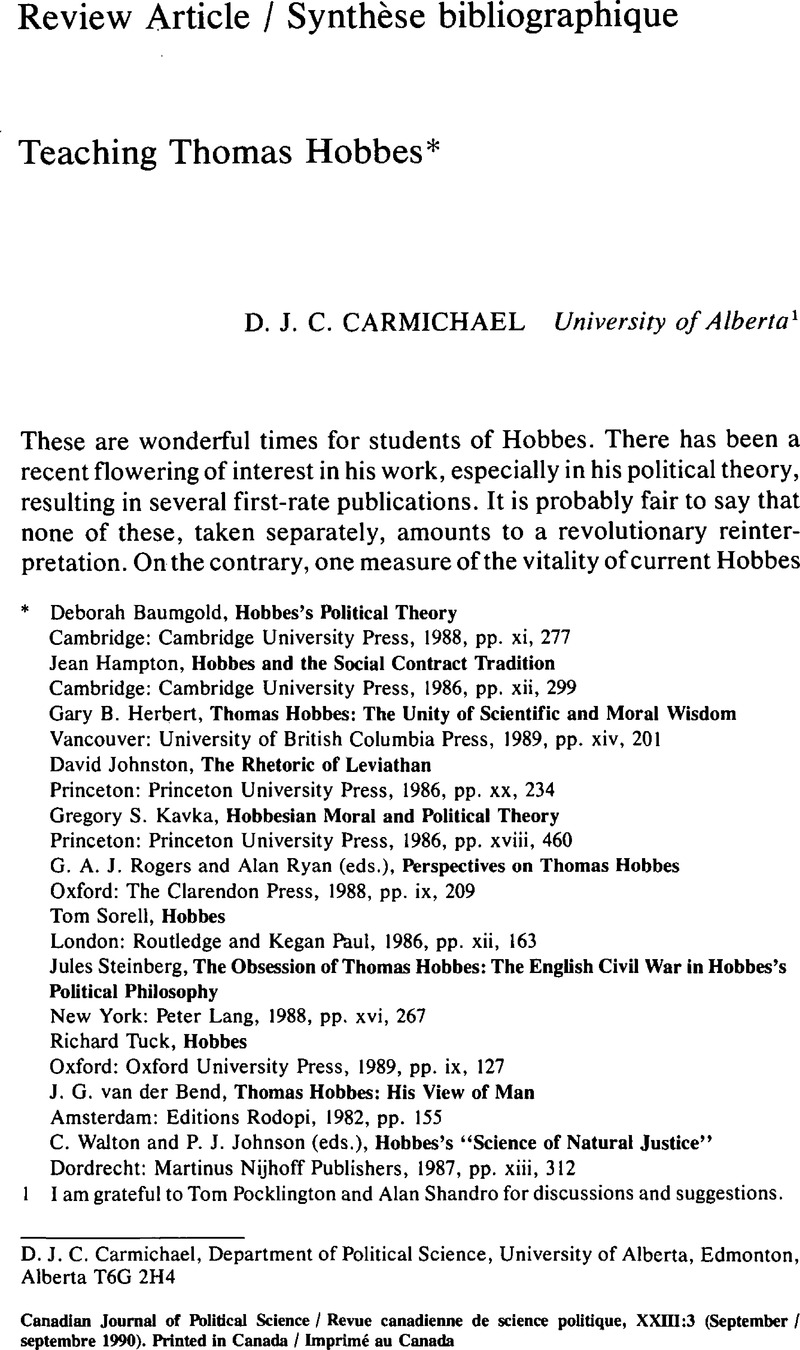

Teaching Thomas Hobbes*

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 10 November 2009

Abstract

- Type

- Review Article/Synthèse Bibliographique

- Information

- Canadian Journal of Political Science/Revue canadienne de science politique , Volume 23 , Issue 3 , September 1990 , pp. 545 - 555

- Copyright

- Copyright © Canadian Political Science Association (l'Association canadienne de science politique) and/et la Société québécoise de science politique 1990

References

2 Tuck, Hobbes, 69–76.

3 Ibid., 72.

4 Larry May, “Hobbes on Equity and Justice,” in Walton and Johnson, Hobbes's “Science of Natural Justice,” 241–52. See also Mathie's “Commentary,” 253–56.

5 William Mathie, “Justice and Equity: An Enquiry into the Meaning and Role of Equity in the Hobbesian Account of Justice and Politics,” in Ibid., 274.

6 “Editor's Introduction,” in Ibid., 14.

7 Much of this account can be found abbreviated in Baumgold, Deborah, “Hobbes's Political Sensibility: The Menace of Ambition,” in Dietz, Mary G. (ed.), Thomas Hobbes and Political Theory (Lawrence, Kan.: University of Kansas Press, 1990), 74–90.Google Scholar

8 This is a standard criticism, but Baumgold is replying specifically to Walzer's, Michael argument in “The Obligation to Die for the State,” in Obligations: Essays on Disobedience, War, and Citizenship (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1970), 77–98.Google Scholar

9 Originally reviewed in this Journal 20 (1987), 455–56 by Thomas J. Lewis.

10 Lewis, Thomas J., “On Using the Concept of Hypothetical Consent,” this Journal 22 (1989), 793–807.Google Scholar Lewis had criticized Kavka's book on this point in his original review.

11 Johnston, The Rhetoric of Leviathan, 67.

12 Hobbes, , Leviathan (Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin Books, 1968), 136–37.Google Scholar

13 Tom Sorell, “The Science in Hobbes's Politics,” in Rogers and Ryan (eds.), Perspectives on Thomas Hobbes, 67–80.

14 Reviewed by Desserud, Don in this Journal 23 (1990), 177–78.Google Scholar

15 Bernard Wilms, “Tendencies of Recent Hobbes Research,” in van der Bend, Thomas Hobbes: His View of Man, 154.

16 Dietz (ed.), Thomas Hobbes and Political Theory. See the review on pages 619–21.