The majority of older adults will experience normal age-related cognitive changes (Craik & Rose, Reference Craik and Rose2012), for which an increasing number of training programs have been created to optimize memory functioning. Research shows that memory interventions can improve performance on trained memory tasks (Karbach & Verhaeghen, Reference Karbach and Verhaeghen2014), increase knowledge about memory, and promote healthy lifestyle changes to support brain health (Vandermorris, Au, Gardner, & Troyer, Reference Vandermorris, Au, Gardner and Troyer2020), and bolster self-reported memory abilities and strategy use in daily life (Hudes, Rich, Troyer, Yusupov, & Vandermorris, Reference Hudes, Rich, Troyer, Yusupov and Vandermorris2019).

Although many older adults who experience cognitive changes are proactively looking for ways to keep their brain active (Parikh, Troyer, Maione, & Murphy, Reference Parikh, Troyer, Maione and Murphy2016), there are several limitations to doing this through in-person intervention programs. Participation may be restricted for some individuals for a variety of reasons such as difficulties traveling to the site because of physical disabilities, limited access to transportation, or living in remote areas (Fitzpatrick, Powe, Cooper, Ives, & Robbins, Reference Fitzpatrick, Powe, Cooper, Ives and Robbins2004; Pike et al., Reference Pike, Chong, Hume, Keech, Konjarski and Landolt2018) or cancellation of in-person group activities, as seen during the COVID-19 pandemic. In response to the pandemic, the already increasing rate of technology use among older adults has surged, with more than 88 per cent of Canadians over the age of 65 using the Internet daily (AGE-WELL, 2020). More specifically, although this is an emerging field, research shows that older adults do benefit from online cognitive programs (for a review, see Kueider, Parisi, Gross, & Rebok, Reference Kueider, Parisi, Gross and Rebok2012). Therefore, creating an online memory intervention may increase accessibility to a broader audience and offer greater convenience, privacy, and flexibility in scheduling for participants.

In considering an online program, it is important to acknowledge that online interventions often have higher rates of attrition than in-person interventions. For example, a systematic review of 83 online health interventions found an adherence rate of approximately 50 per cent (Kelders, Kok, Ossebaard, & van Gemert-Pijnen, Reference Kelders, Kok, Ossebaard and van Gemert-Pijnen2012). Personalization of online interventions is essential for promoting participant engagement and satisfaction, thus leading to greater adherence and efficacy of the given program. One avenue to achieve personalization is to develop an online program for a target group and to effectively understand the target group’s needs during the design process (Ludden, van Rompay, Kelders, & van Gemert-Pijnen, Reference Ludden, van Rompay, Kelders and van Gemert-Pijnen2015). In a recent review of online memory programs for older adults, Pike et al. (Reference Pike, Chong, Hume, Keech, Konjarski and Landolt2018) offer practice recommendations for their development including considering age-associated sensory and cognitive changes in the program’s design, while ensuring that the program is easy to learn and intuitive. However, no specific recommendations are provided to inform the development process and its piloting in order to gauge usability.

Agile Development Cycle

In this article, we describe the successful application of an agile development cycle to the creation of an online memory intervention program for older adults. An agile development cycle is an iterative process adapted from the technology sector that incorporates end users’ feedback during each phase of program development and piloting (Davis, Reference Davis2013). This approach is in contrast with the traditional Waterfall Models (e.g., the ADDIE model which involves the Analysis, Design, Development, Implementation, and Evaluation stages) for instructional design and development, which are essentially linear, inflexible approaches that require the completion of each phase prior to moving on to the next (Stoica, Ghilic-Micu, Mircea, & Uscatu, Reference Stoica, Ghilic-Micu, Mircea and Uscatu2016). The assumption underlying Waterfall Models is that developers possess all the necessary information for the designing process (Doolittle, Reference Doolittle2020). An agile development cycle, in contrast, is better suited for developing online learning programs for specific populations (i.e., older adults) because it allows for tailoring the program to their unique needs, which may not be fully known or understood at the onset. It also allows for flexibility in making modifications to preceding phases of design (Davis, Reference Davis2013; see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Illustration of the traditional Waterfall Model in contrast to the agile development cycle, which has the fluid capability to return to preceding phases of testing and development.

Translational Phases

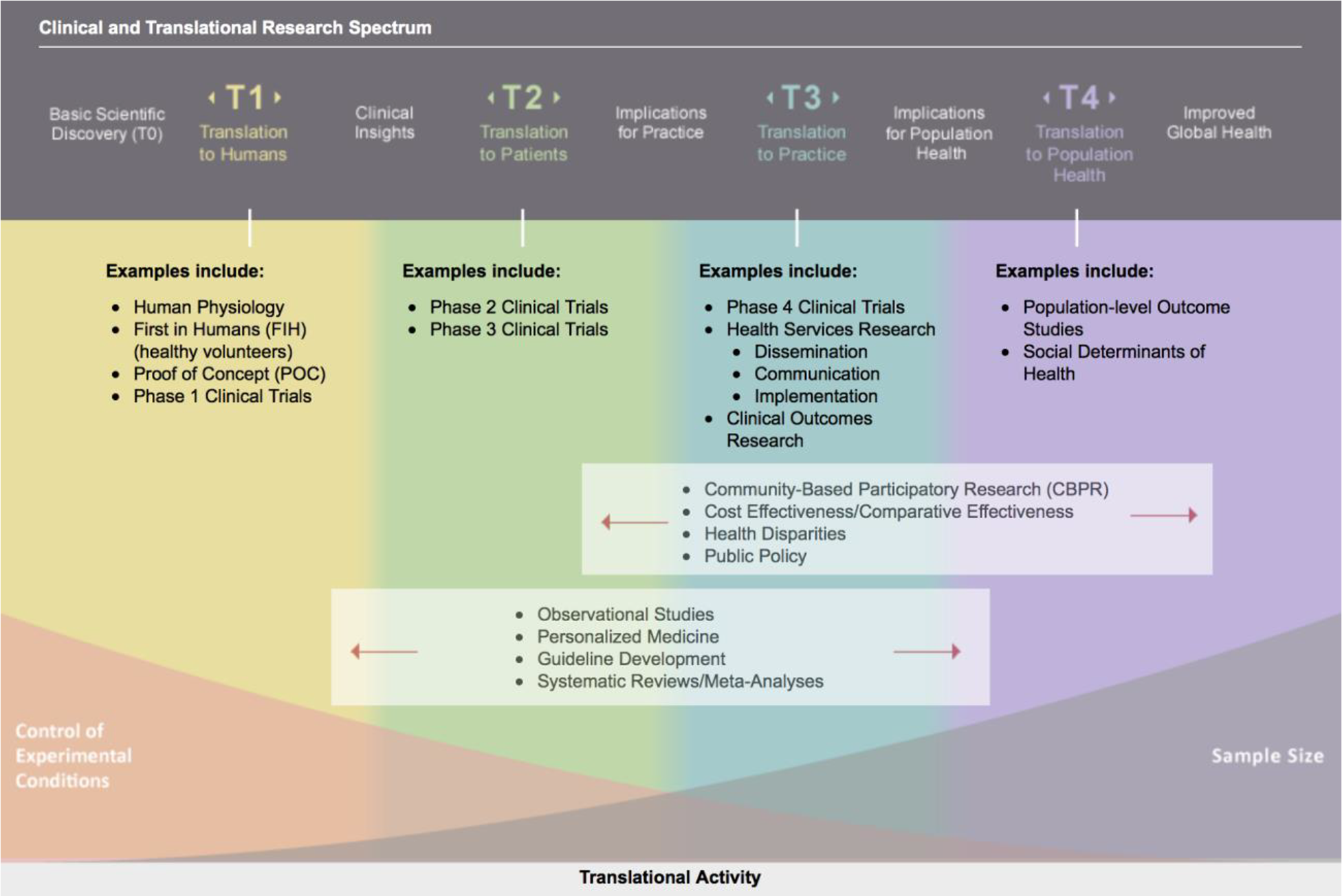

Considering that the agile development cycle is adapted from the technology sector, we combined this process with the framework from the Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center’s five translational (T) phases that are necessary to execute before a health intervention can become available to the general public (Harvard Catalyst, 2021). In the next section, we describe the foundational work of the first two phases, which involve seeking evidence from the extant literature (T0) and proof of concept for the online intervention (T1). The current research focuses on the subsequent phases, which involves testing the intervention in a controlled environment (T2) and testing the intervention in the intended environment of the final product (i.e., remotely accessed) while assessing preliminary program outcomes (T3). The final phase evaluating benefits under a more rigorous research design (T4) is discussed as a future step in the discussion. See Figure 2 for an infographic of the phases, based on material from Sung et al. (Reference Sung, Crowley, William, Genel, Salber and Sandy2003), Szilagyi (Reference Szilagyi2009), and Westfall, Mold, and Fagnan (Reference Westfall, Mold and Fagnan2007).

Figure 2. Overview of the Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center’s five translational phases; adapted framework for the testing of a health intervention prior to its release to the general public.

Foundational Work

T0: Basic Research

The first translational phase, T0, involves understanding the biopsychosocial mechanisms of an underlying health problem and seeking opportunities for its treatment (Harvard Catalyst, 2021). As reviewed, older adults can benefit from carefully crafted memory programs grounded in research on effective memory strategies and modifiable lifestyle factors. Further, Pike et al. (Reference Pike, Chong, Hume, Keech, Konjarski and Landolt2018) recommend considering existing and effective in-person memory programs when developing an online program. Based on this literature, we chose to develop an online program modelling an empirically validated in-person memory intervention called The Memory & Aging Program®, which has been offered for more than 20 years at Baycrest, a global leader in geriatric research and care in Toronto (Troyer, Reference Troyer2001). This program aligns with practice recommendations by Pike et al., as it offers its participants psychoeducation on aging and memory, a “tool kit” of memory strategies, and group discussions (Troyer & Vandermorris, Reference Troyer and Vandermorris2012).

Benefits of the Memory and Aging Program include increased memory knowledge and strategy use, increased satisfaction and confidence with one’s everyday memory functioning (Troyer, Reference Troyer2001), positive change in healthy lifestyle domains (Vandermorris et al., Reference Vandermorris, Au, Gardner and Troyer2020), decrease in intentions to seek unnecessary medical attention for memory concerns (Wiegand, Troyer, Gojmerac, & Murphy, Reference Wiegand, Troyer, Gojmerac and Murphy2013), and feelings of acceptance and reduced anxiety about normal age-related memory changes (Vandermorris et al., Reference Vandermorris, Davidson, Au, Sue, Fallah and Troyer2017).

T1: Translation to Humans

The second translational phase, T1, involves proof of concept and understanding the feasibility of translating the original in-person intervention into an online format (Harvard Catalyst, 2021). A multidisciplinary team was created that included research and clinical neuropsychologists (A.K.T., S.V.) and instructional design and e-learning development experts (including C.P.). Patient advisors (e.g., graduates of the in-person program) also provided input.

The multidisciplinary team used program materials for the in-person program (Troyer & Vandermorris, Reference Troyer and Vandermorris2012; Reference Troyer and Vandermorris2017) and followed the next steps for creating a new e-learning program, including:

-

1. Action Mapping, which began with assigning roles within the e-learning team, discussing delivery method of material, and creating a timeline for task deadlines. This step focused on solving performance problems and setting measurable learning outcomes for the program.

-

2. Storyboarding, which involved creating a storyboard template, with all content reviewed by the team. Next, design elements such as themes, colour scheme, narration, and interactions were discussed and confirmed. A delivery date was set.

-

3. Design and Development, which involved taking all information determined in the Action Mapping and Storyboarding stages and applying instructional design and development for online learning best practices to produce the e-learning program.

The initial version of the program was developed (see Table 1 for a brief description of each module) and based on themes that emerged from brainstorming sessions and patient advisor feedback, certain elements were included. For example, as privacy of personal information is a significant concern for older adults (Chang, McAllister, & McCaslin, Reference Chang, McAllister and McCaslin2015), participants were provided with the option of using a non-identifying username as opposed to their real names. They were also informed that information would remain private within the program and accessible only to other registered participants.

Table 1. Description of individual modules in the online Memory and Aging Program

Current Study

Based on the foundational T0 and T1 work described, we used an agile development cycle to implement and evaluate translational phases T2 and T3, which are reported separately in the following two studies. Study 1 involved piloting individual program modules on site and integrating participant feedback into the program’s design to optimize usability, with the primary aim of executing the T2 translational phase. Study 2 involved two sequential pilots of the program accessed remotely to evaluate preliminary clinical outcomes that have been demonstrated in the in-person Memory and Aging Program. The primary aim of Study 2 was to successfully execute the T3 translational phase and to continue making modifications using participant feedback as per the agile development cycle.

Study 1: Translation to Patients

Methods

In this T2 phase, the intervention program was tested in a highly controlled environment (i.e., on site in a computer laboratory; Harvard Catalyst, 2021).

Participants

A total of 25 participants were involved in this phase, including local community-dwelling older adults recruited through an e-mail advertisement from a pool of hospital volunteers unfamiliar with the Memory and Aging Program (n = 21) and through direct requests to individuals who previously completed the in-person Memory and Aging Program (n = 4).

Procedure and Measures

Participants provided written informed consent for audio recording of spoken feedback and photography of their engagement with the technology. The essence of the agile development cycle involves breaking down the larger intervention into smaller cycles (known as Sprints) and offering incremental delivery of the intervention components (Flewelling, Reference Flewelling2018). Therefore, of these 25 participants, 14 piloted Modules 2, 3, and 5; 7 piloted Modules 4, 6, and 7; and 4 (the graduates of the in-person program) piloted Module 8. Feedback from the first pilot (Modules 2, 3, and 5) was discussed within the multidisciplinary team, and modifications were made to the proceeding modules prior to the subsequent piloting cycles. This process was repeated after each piloting session.

Clinical, research, and e-learning staff observed the participants as they engaged in the modules, paying special attention to their reactions and noting any areas of confusion and particular enjoyability. Participants filled out feedback questionnaires (The Scavenger Hunt measure from the TUNSGTEN tools: http://tungsten-training.com) for each module that assessed usability of new technologies in interactive settings by indicating yes or no to the following statements: (a) This is easy to use, (b) This is something I would use, and (c) This is something I enjoy (Astell, Dove, Morland, & Donovan, Reference Astell, Dove, Morland, Donovan, Brankaert and Kenning2020). The questionnaire also encouraged participants to add general comments or suggestions for improvement, to enable technologies to be modified to better meet the user’s needs. These were used as the guiding structure for the focus groups that followed.

Results

Piloting of Modules 2, 3, and 5 (Understanding Memory, Modifiable Lifestyle Factors, and Memory Strategies)

Piloting of these modules revealed that all 14 participants found at least one of the three modules easy to use, enjoyable, and something that they would use outside of the laboratory setting. Seven of 14 participants reported such feelings about all three of the piloted modules. Module 5, which involved an interactive component, was reportedly enjoyed by all but one participant. For example, one participant reported, “This module works well. Interactive and fun. Nice customization. Well done.”

Feedback was reviewed, and several rounds of modifications were made. In general, there appeared to be difficulties with navigating the modules, as some procedures that may seem intuitive to an avid technology user were not obvious to the participants, including how to adjust the sound, pause the videos, or select items.

Piloting of Modules 4, 6, and 7 (Stress and Relaxation, Practicing Memory Strategies, and Strategies Overview)

Information gained from the first series of piloting previously detailed was incorporated into the design of Modules 4, 6, and 7 prior to in-person piloting. Responses revealed that all seven participants from this pilot session found at least one of the three modules easy to use, enjoyable, and something that they would use outside of the laboratory setting, and four participants found that all three piloted modules met these criteria.

Piloting of Module 8 (Summary and Wrap-up)

Module 8 consists of a review game, final thoughts, and creating a plan for memory or health improvement (i.e., setting goals). These components were piloted by graduates of the in-person Memory and Aging Program, as they possessed the background information requisite to participate in the review game and provide meaningful feedback on the way that the course content was summarized. With the exception of one participant who noted “maybe” to the questions about enjoyment and using the review game in a real-life setting, all four participants reported that each of the three components of Module 8 was easy to use, enjoyable, and something that they would use outside of the laboratory setting. Specific feedback included, “Good practice run for refresher of what I learned in the program.”

Qualitative feedback

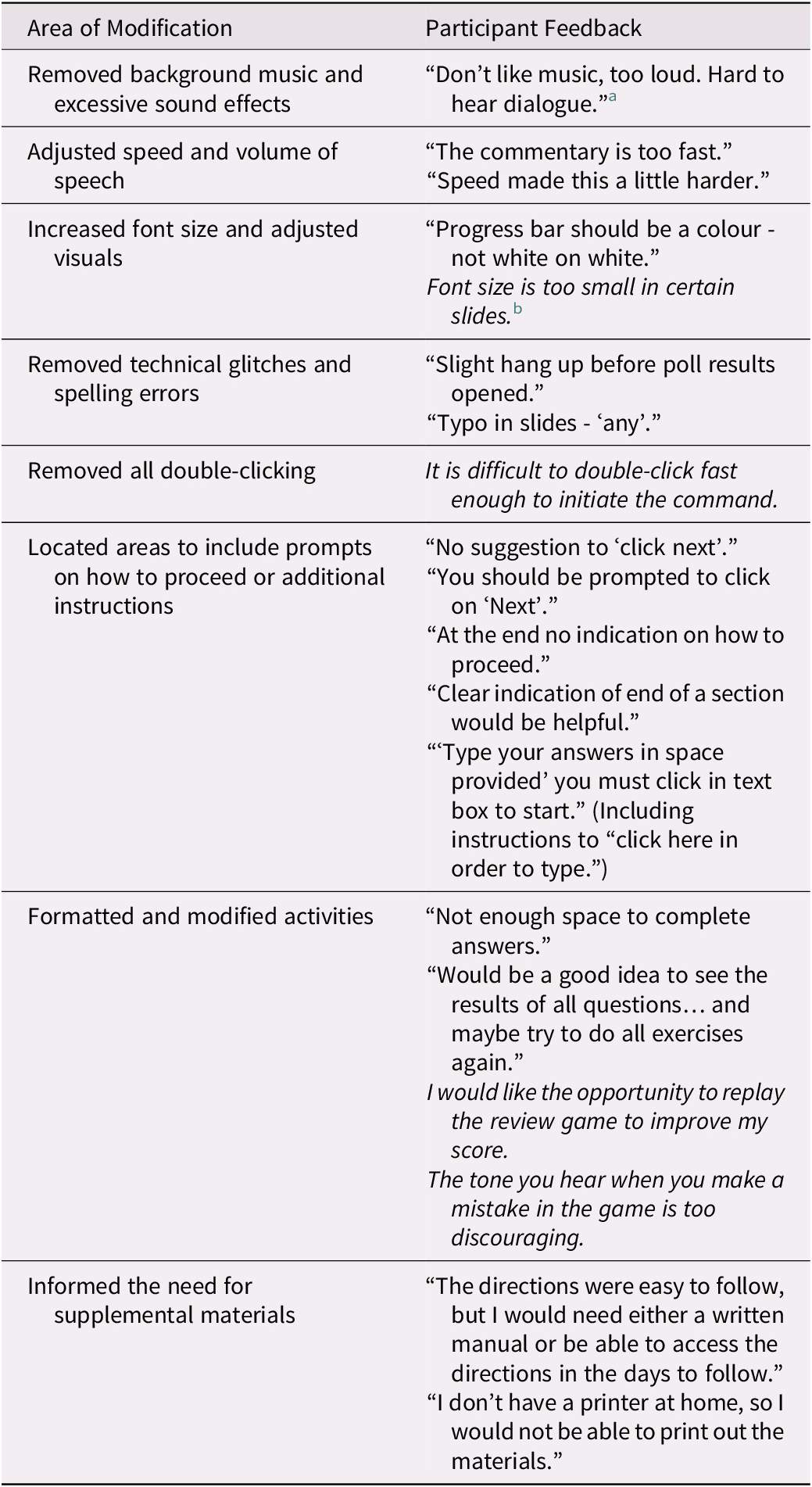

Qualitative feedback (i.e., from the open-ended questionnaire responses and focus group discussion) from all 25 participants identified a number of technological glitches and settings that needed adjustment. Subsequent modifications based on this feedback involved removing background music and excessive sound effects, removing the requirement for double-clicking, increasing font size, adjusting speed and volume of speech, and inserting additional prompts and instructions on how to proceed (e.g., a pop-up indicating “click ‘next’”). See Table 2 for more detailed participant feedback.

Table 2. Overview of Study 1 feedback and areas of modification

Note.

a Feedback in quotations is extracted from the written feedback questions.

b Information written in italics represents gist themes reported from the audio-recorded focus group discussions.

Study 2: Translation to Practice

Methods

Study 2 involved testing the intervention in its entirety in the intended environment for the final product (i.e., accessed remotely by participants within their community) in two separate pilot studies. In addition, we tested preliminary clinical outcomes by incorporating targeted measures that have been shown to improve following participation of the in-person program characteristic of the T3 Translation to Practice phase (Harvard Catalyst, 2021). The results of each pilot are reported separately as Sub-study 2a and Sub-study 2b (with the exception of the results from the Memory Toolbox questionnaire and program-specific goal attainment, which were pooled across both pilots and reported under Sub-study 2b).

Participants

Forty community-dwelling older adults in Canada were recruited through e-mail advertisements to participate remotely (22 participated in the first pilot and 18 participated in the second pilot). In light of a recent study that found that less frequent computer usage predicted attrition in the initial phases of online studies (Rübsamen, Akmatov, Castell, Karch, & Mikolajczyk, Reference Rübsamen, Akmatov, Castell, Karch and Mikolajczyk2017) and in the hope of mitigating participant distress during the early stages of piloting, participants were required to self-report using a computer at least once a day and to feel comfortable or very comfortable using a computer.

Procedure

Participants completed online questionnaires and a telephone interview prior to the intervention (detailed subsequently). Participants were then e-mailed a link to register for the online Memory and Aging Program. Once registered, they were able to complete the pre-intervention questionnaires and watch the introduction videos. Each module was released on a weekly basis as long as the participant had completed all tasks in the previous module. The e-learning team monitored the completion of individual items for each participant. Once it was apparent that participants had completed the program (i.e., all of the modules described in Table 1), they filled out post-intervention questionnaires online and completed an interview over the telephone.

Measures

In order to gauge the program’s benefits, participants completed the following memory-related measures before and after completion of the intervention.

The Memory Knowledge Quiz. During the telephone interview, participants were asked 12 open-ended questions related to memory knowledge and brain health. Each answer was scored from 1 to 6 points, depending on the demand of the question. The Memory Knowledge Quiz was adapted from previous evaluations of the in-person version of the Memory and Aging Program (Troyer, Reference Troyer2001).

The Memory Toolbox. This online questionnaire provided participants with six familiar scenarios (e.g., learning the name of a new acquaintance), for which they were required to list memory strategies that would be useful for each situation (Troyer, Reference Troyer2001). The number and quality of memory strategies were analyzed before and after the program.

Lifestyle behavior change. As part of the online questionnaires, a subset of participants (n = 10) were asked about their lifestyle behaviors with the following question: “Have you made any lifestyle changes in the past month that may improve your health and possibly memory (e.g., lower stress levels, use of relaxation techniques, improved diet or exercise, engagement in cognitively or socially engaging activities)?”

Program-specific goal attainment and general feedback. Similar to the in-person program, participants were asked to choose three program-specific goals that best aligned with their intentions for the program prior to its start (e.g., to understand how lifestyle factors affect memory, to feel more confident about their memory). During the post-intervention telephone interview, participants were reminded of their three goals and were asked to rate them on a five-point satisfaction scale. General feedback related to the program and suggestions for improvement were collected during the telephone interview and in an online questionnaire.

Results

Sub-study 2a

Of the 22 recruited participants, 11 completed all modules and the post-intervention telephone interview; 10 of these 11 participants also completed the online post-intervention questionnaires. Several areas of technical difficulty including registration, password creation, and browser compatibility were reported through e-mail communications to the e-learning team.

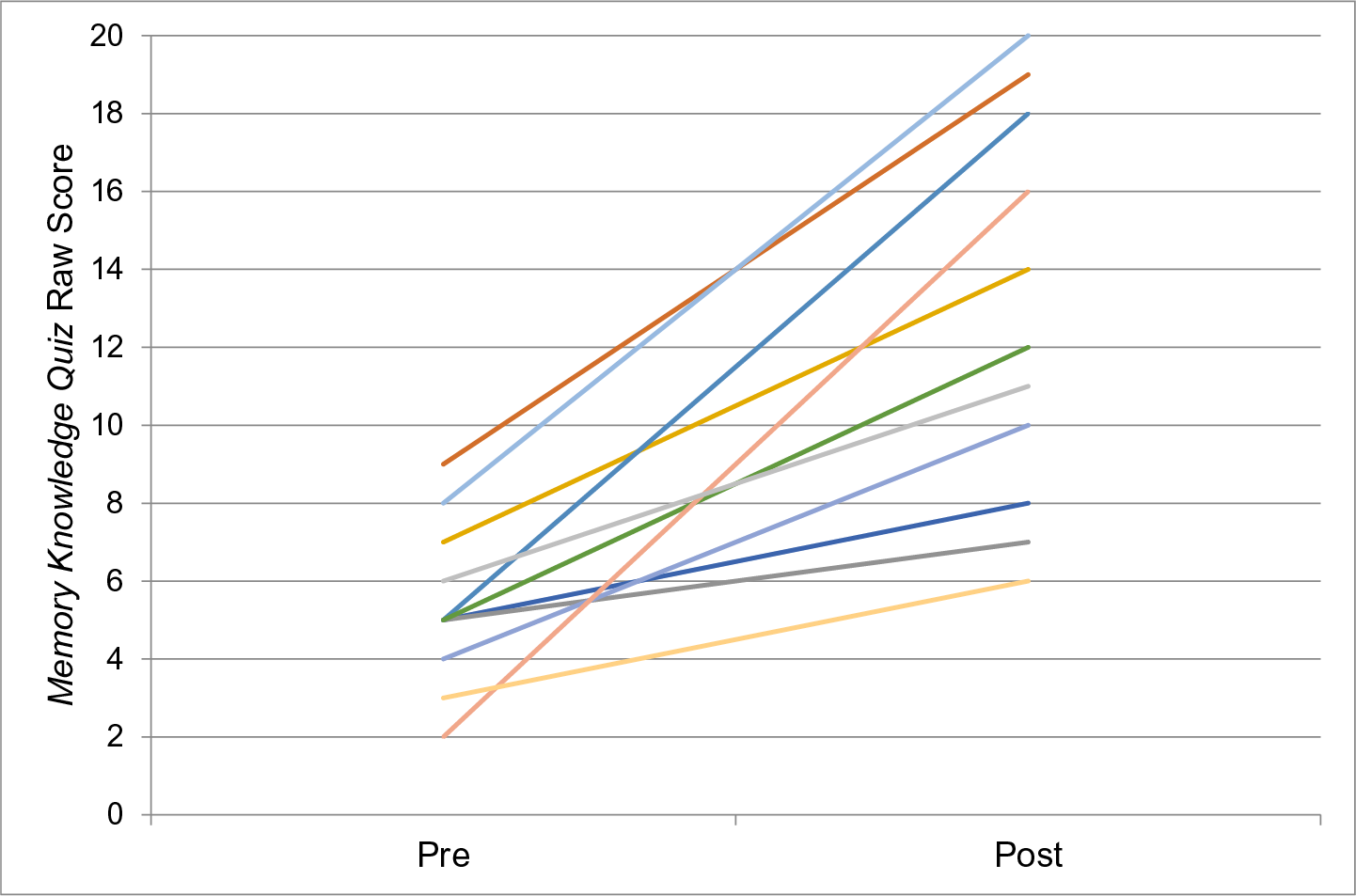

Memory knowledge and strategy use. For the 11 participants who completed the Memory Knowledge Quiz, scores showed a large, significant improvement from before to after program completion t(10) = -5.85, p < 0.001, d = 1.76. Individual scores are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Pre- and post-intervention individual participant scores on the Memory Knowledge Quiz during Sub-study 2a in the T3 Translation to Practice phase.

Note. n = 11, maximum possible score of 20.

Ten participants completed the Memory Toolbox questionnaire. In the post-intervention responses, one participant applied three new memory strategies, three applied two new memory strategies, and six applied one new memory strategy. Therefore, all 10 participants learned at least one new memory strategy that they could apply in real-life scenarios. These data were combined with data from Sub-study 2b for statistical analysis and are reported in the Sub-study 2b results section.

Lifestyle behavior change. Participants were also asked about changes in their lifestyle behaviors (e.g., use of relaxation techniques, improved diet or exercise, engagement in cognitively or socially engaging activities). Five of the 10 participants reported that they did not make any lifestyle changes in the month prior to the commencement of the online program, but that they had made a lifestyle change following program completion. Two participants indicated they had made a change within the month prior to as well as in the month following completion of the program. The remaining three participants reported before and after the program that they had not made a lifestyle change in the previous month. Based on 20 per cent of individuals making a lifestyle change at baseline, a Chi square analysis revealed that a significant proportion of participants (70%) reported a lifestyle change after completing the program (χ2 = 25, df = 1, p < 0.001).

General feedback

Through post-intervention telephone interviews and online questionnaires, participants provided general feedback and favourable ratings for their program goals (reported under Sub-study 2b). Overall, they expressed enjoyment of the various presentation formats (i.e., videos, animations, games), which kept them engaged throughout the modules. Feedback was generally positive regarding the interactive nature of the online program, such as the use of real-world examples and cartoon animations that depict common and relatable scenarios. Some participants also mentioned the usefulness of having a transcript of each slide in order to follow along with the audio component. Finally, participants expressed feelings of normalization about their memory ability.

Participants who experienced technical difficulties were able to e-mail the project coordinator and receive support from the e-learning team; thus, all areas of difficulty were systematically logged. Subsequently, a “Getting Started” module was added to include an introduction to various program features (such as accessing the transcript, adjusting volume, and posting in the discussion forum). In addition, a Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) document was compiled, containing all of the areas of concern or difficulty that had been recorded.

For the homework assignments, individual exercise sheets were available for participants to print and utilize. However, some participants reported that they did not have access to a printer. This is in line with the feedback from the T2 Translation to Patients phase involving the in-person Memory and Aging Program graduates who spoke about the utility of having a participant workbook. Another subject that participants mentioned was the need for fostering greater interaction. Although there were discussion boards, there was little back and forth conversation amongst participants. In order to increase participant interaction, weekly “coffee breaks” were held as a live chat room for the participants and the facilitator to interact with each other.

Sub-study 2b

Because of the flexible and iterative nature of the agile development cycle, we returned to making modifications to individual modules by integrating the feedback from Sub-study 2a prior to launching Sub-study 2b. The goal of Sub-study 2b was to ensure that the technical glitches were resolved, obtain feedback regarding the addition of the participant workbook (mailed to the participants’ homes) and the “coffee break” chat rooms, and continue assessing program outcomes. Of the 18 participants, 9 completed the online Memory and Aging Program as well as the post-intervention telephone interview to obtain feedback. Seven of these participants also completed the online version of the Memory Toolbox questionnaire, which was administered to continue to monitor the benefits of the program content itself and participant engagement with material, and 11 provided ratings for their program goals.

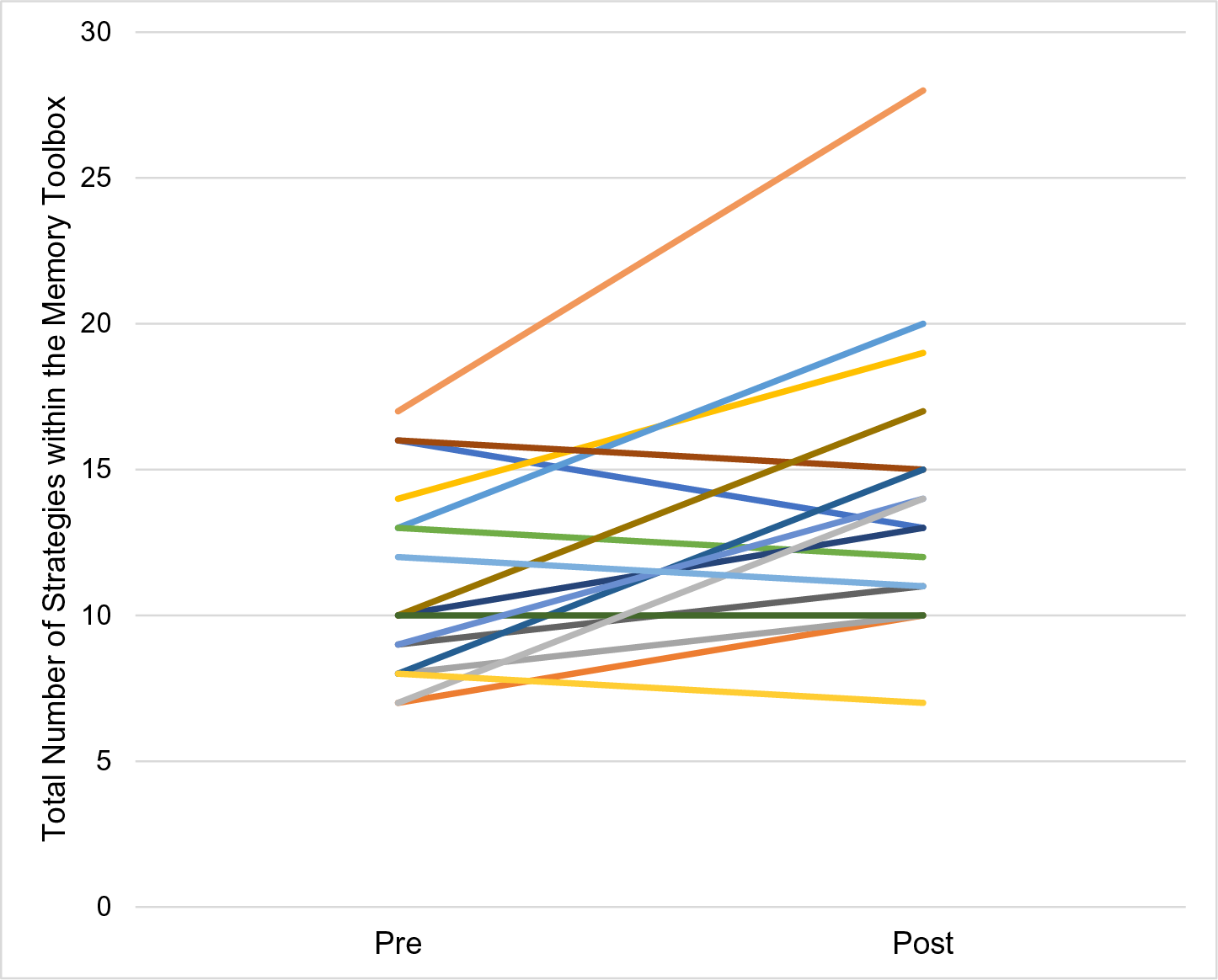

Memory Toolbox. Results of the pre- and post-intervention Memory Toolbox questionnaire indicated that all but one participant acquired and applied a new memory strategy; three out of seven added three strategies, two out of seven added two strategies, and one participant added one new strategy (see Figure 4). Across Studies 2a and 2b, participants were able to provide a significantly greater number of strategies for the given scenarios after program completion, t(16)= -3.21, p < 0.001, d = 0.78. An examination of the types of responses revealed a particular acquisition of internal strategies, such as paying close attention and forming implementation intentions (e.g., saying “I am turning off the stove” when doing so). In contrast, external strategies, such as keeping a record book or agenda, were most frequently listed as useful strategies by participants prior to participation in the online program.

Figure 4. Pre- and post-intervention individual participant scores on the Memory Toolbox questionnaire during Sub-studies 2a and 2b in the T3 Translation to Practice phase.

Note. n = 17

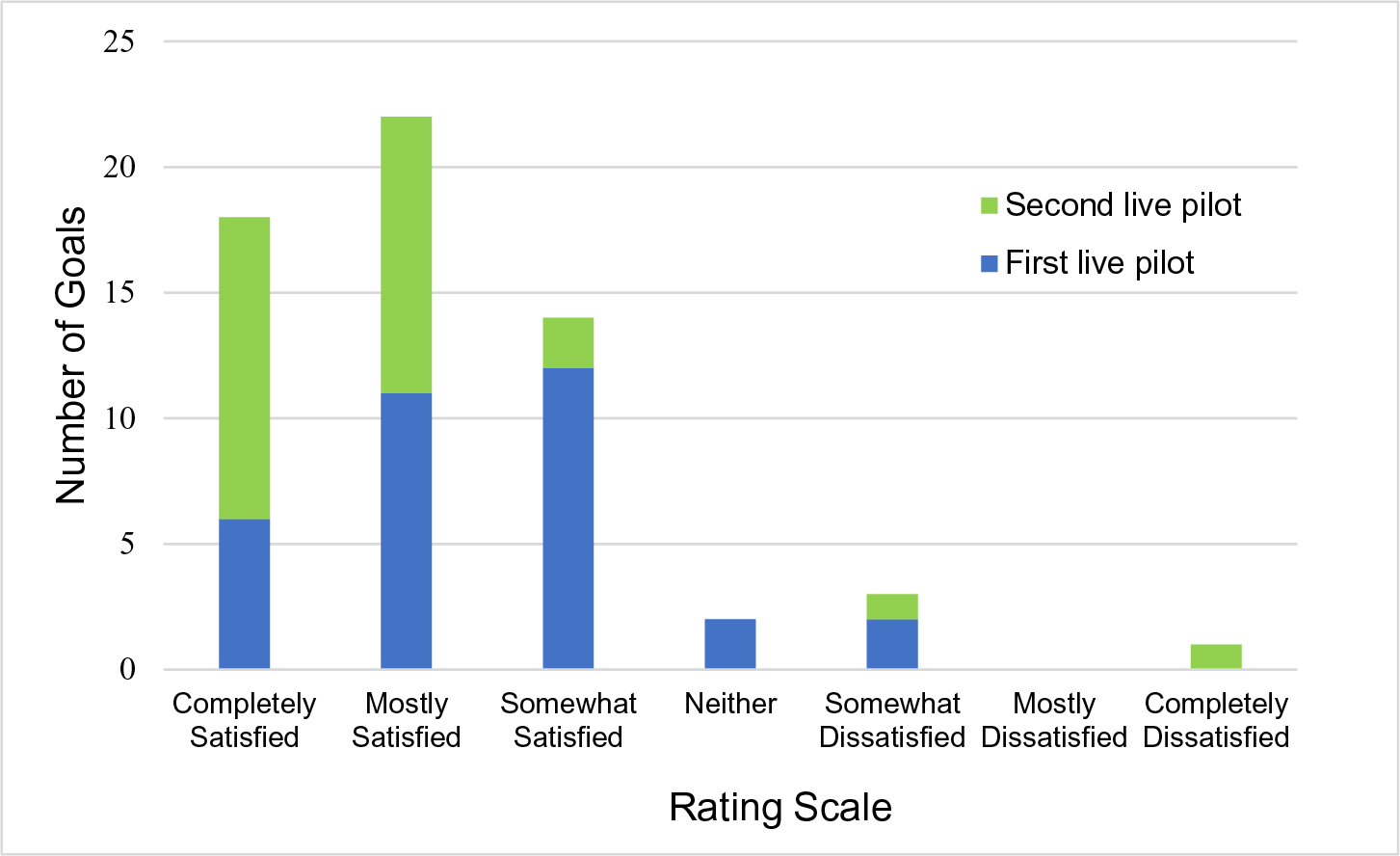

Program-specific goal attainment. Across Sub-studies 2a and 2b, a total of 20 participants provided a rating for their three personal goals. Overall, all participants (n = 20) were at least somewhat satisfied with at least one of their chosen goals; 16 participants were at least mostly satisfied with at least one of their goals, and 7 participants were completely satisfied with at least one of their goals (see Figure 5). The large majority of goals (54 out of 60) were rated positively, indicating that participants were getting what they wanted out of the program.

Figure 5. Program-specific individual goal satisfaction ratings from Study 2.

General feedback

Through the post-intervention telephone interview and online questionnaires, all but one of the participants reported feeling satisfied with the participant workbook. This participant mentioned that the workbook was an unnecessary addition, as links to downloadable homework logs were available. Several participants suggested that there ought to be specific instructions within the online program to guide users to the book, such as indicating which pages were associated with a certain module and where the homework page was located. In general, participants did not utilize the “coffee break” chat rooms because of technical glitches, lack of interest, and scheduling conflicts.

Lastly, participants shared a sense of relief when learning about normal age-related memory changes experienced by most adults. They also tended to feel more in control of their memory, with one participant indicating that the best part of the program was “motivating me to take charge and that I shouldn’t be so quick to accept that losing some memory is unavoidable.” Additionally, participants consistently attributed their enjoyment and engagement to the many types of formats, games, activities, and homework.

Final iterations

Based on the feedback obtained throughout the agile development cycle, several final changes were made (e.g., adding to the FAQ document, dropping the “coffee break” chat rooms, making discussion board questions more open-ended). It was further decided that there would be increased moderation within the discussion boards, as having encouraging feedback, inviting participant responses, and redirecting to the goal of the topic at hand can increase engagement and provide an organized structure (Cudney & Weinert, Reference Cudney and Weinert2000; Nahm et al., Reference Nahm, Bausell, Resnick, Covington, Brennan, Mathews and Park2011). This can also be an opportunity for the facilitator to reinforce and elaborate on evidence-based information regarding memory and health, debunk any common misconceptions, and promote feelings of normalcy among participants (Pike et al., Reference Pike, Chong, Hume, Keech, Konjarski and Landolt2018).

Attrition in Study 2 was in part the result of technical obstacles, according to participant e-mails notifying the e-learning team. Despite addressing technical issues between Sub-studies 2a and 2b, the attrition rate remained at 50 per cent. The schedule was structured to release a module once a week, as long as the participant had completed the previous module. This resulted in a minimum requirement of 8 weeks of participation in the online program. Some participant feedback from open-ended questions indicated confusion surrounding when the module would be released as well as concern from participants travelling without access to a computer. Further, participants may lose interest if there is a long wait period before the next module is released. Therefore, in future versions of the program, participants will be able to access the next module after completion of the preceding activities, which will allow participants to complete the program at their desired pace.

General Discussion

Development of Online Memory Programs

Over the coming years, there will undoubtedly be an increasing number of online health programs to serve the aging Canadian population. Although there are practice recommendations to tailor memory programs to the unique needs of older adults (Pike et al., Reference Pike, Chong, Hume, Keech, Konjarski and Landolt2018), this is the first article to provide a detailed description of a process that can be adapted to achieve such personalization. For example, Rebok, Tzuang, and Parisi (Reference Rebok, Tzuang and Parisi2020) did not provide information related to the development of their online memory training program, ACTIVE Memory Works™, and did not describe any piloting conducted prior to their randomized study. In a recent publication of a study protocol for the online memory program OPTIMiSe (Pike et al., Reference Pike, Moller, Bryant, Farrow, Dao and Ellis2021), there is mention of obtaining feedback from an “advisory committee” consisting of health experts and individuals from the target group. However, there is no indication of whether or how any feedback was integrated into the final protocol, and whether the program was pilot tested on any end users.

Overall, adapting an agile development cycle fostered collaboration and supported inclusion of important input from diverse stakeholders. We were open to the process of small changes and many iterations, and adopted a sense of flexibility with timelines and the number of piloting sessions needed to produce the final product. In addition, following the five clinical and translational phases offered a clear framework and structure to the project. Through this process, we provided evidence that our online memory program was designed to be user friendly and enjoyable, while demonstrating preliminary benefits associated with the in-person version. In the future, researchers can consider including a user experience (UX) designer to facilitate the agile process and to video record piloting sessions in order to systematically code and evaluate users’ experience, similarly to the methodology applied in Mansson et al.’s (Reference Mansson, Wiklund, Öhberg, Danielsson and Sandlund2020) co-creation of a smart phone application with older adult end users. Although analytic data were monitored to track program progress in Study 2, future avenues for research include analyzing data to further investigate any areas of navigation difficulty and whether there are any associations between analytics (e.g., average length of time between the completion of various modules) and program benefits.

Following the successful completion of the T2 and T3 translational phases described in this article, future research is ongoing to conduct a wider implementation of the online memory program to evaluate true benefits within the community characteristic of the final T4 Translation to Population Health phase. Specifically, as a first step in this process, we are currently conducting a randomized controlled trial to evaluate benefits of participating in the program in comparison with a no-intervention control group (i.e., treatment as usual for healthy older adults; Petersen et al., Reference Petersen, Lopez, Armstrong, Getchius, Ganguli and Gloss2018).

Limitations

Study 2 had 50 per cent attrition across the two sequential pilots. This was not unexpected, however, because online interventions tend to have higher rates of attrition than in-person interventions (Eysenbach, Reference Eysenbach2005; Kelders et al., Reference Kelders, Kok, Ossebaard and van Gemert-Pijnen2012; Peels et al., Reference Peels, Bolman, Golsteijn, De, Mudde, van Stralen and Lechner2012). High attrition rates may occur for a variety of reasons such as the fleeting or “surfing” culture of the Internet (Ahern, Reference Ahern2007). It may be that participants feel a greater sense of responsibility or investment when participating in person as there is more rapport established between intervention facilitators and other group members. According to Eysenbach (Reference Eysenbach2005), attrition is “one of the fundamental characteristics and methodological challenges in the evaluation of eHealth applications” (p. 2). Understanding the reasons for participant attrition from online interventions and being able to predict or control such attrition is an emerging area of research. Although data were logged for participants who volunteered their reasons for leaving the study, we did not routinely inquire about the reasons for discontinuation in cases for which this was not offered. Therefore, this is an area in need of future systematic research; for example, using a feedback questionnaire designed to understand the reasons for discontinuing an online program. It would be interesting to explore what information can be used to understand group differences between individuals who drop out and those who complete an online intervention.

Another important limitation of the described agile development cycle is the extensive use of time and resources. From the first translational phase to the completion of Study 2 (T3 Translation to Patients phase), the project spanned more than 3 years and involved a large multidisciplinary team of researchers, clinicians, e-learning designers, patient advisors, research assistants, and administrative staff. The piloting described in Study 1 required the use of an on-site computer laboratory with headphones. These costs of course are an important consideration in undertaking such a project, but should be weighed against the potential monetary and non-monetary (e.g., poor user experience) costs of making post-implementation revisions if the project was not designed properly in the first place.

Conclusion

Considering the various limitations of in-person programs, there is growing interest in the development of online health interventions for older adults. Although there are clear practice recommendations to tailor online memory programs to the needs of older adults, our article is the first to describe the adoption of the agile development cycle with the clinical and translational phases framework to develop and pilot an online program while integrating feedback from older adults. Through this process, we were able to ensure that our online memory program was user friendly and enjoyable to use, and that it demonstrated targeted program benefits. Such a process can be adapted by others interested in offering online content to a target population.

Acknowledgments

We thank Derek Redmond for his assistance with the software development of the online program and all of the research assistants involved in assisting with data collection.