Introduction

Frailty has been defined as a state of increased vulnerability from age-associated decline in physiologic reserve and function resulting in reduced ability to cope with everyday or acute stressors (Bergman et al., Reference Bergman, Ferrucci, Guralnik, Hogan, Hummel, Karunananthan and Wolfson2007; Xue, Reference Xue2011). It can be conceptualized as the convergence of geriatric and medical conditions, which, along with other factors such as socio-economic circumstances, can lead to greater propensity for health destabilization (Lee, Heckman, & Molnar, Reference Lee, Heckman and Molnar2015). Frailty places older adults at greater risk for adverse outcomes such as recurrent falls, fractures, and disability as well as increased health service utilization and mortality (Fried, Ferrucci, Darer, Williamson, & Anderson, Reference Fried, Ferrucci, Darer, Williamson and Anderson2004; Martin & Brighton, Reference Martin and Brighton2008; McNallan et al., Reference McNallan, Singh, Chamberlain, Kane, Dunlay, Redfield and Roger2013; Shamliyan, Talley, Ramakrishnan, & Kane, Reference Shamliyan, Talley, Ramakrishnan and Kane2013; Tom et al., Reference Tom, Adachi, Anderson, Boonen, Chapurlat, Compston and LaCroix2013). It affects an estimated 10 to 14 per cent of community-dwelling persons aged 65 years and older, and prevalence increases with age and with certain complex chronic conditions (Collard, Boter, Schoevers, & Oude Voshaar, Reference Collard, Boter, Schoevers and Oude Voshaar2012; Shamliyan et al., Reference Shamliyan, Talley, Ramakrishnan and Kane2013). Frailty may affect more than half of older persons with heart failure or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (Jha et al., Reference Jha, Ha, Hickman, Hannu, Davidson, Macdonald and Newton2015; McNallan et al., Reference McNallan, Singh, Chamberlain, Kane, Dunlay, Redfield and Roger2013), and nearly one third of persons with Alzheimer disease (Kojima, Liljas, Iliffe, & Walters, Reference Kojima, Liljas, Iliffe and Walters2017; Robertson, Savva, & Kenny, Reference Robertson, Savva and Kenny2013).

Given the aging population, Canada’s critical shortage of geriatricians, and a health care system challenged to meet the needs of persons living with frailty, it is increasingly recognized that primary care must accept a greater role in the management of frail older adults. As frailty and disability are dynamic and multidimensional involving physiologic, psychological, social, and environmental factors (De Lepeleire, Iliffe, Mann, & Degryse, Reference De Lepeleire, Iliffe, Mann and Degryse2009), primary care physicians are in a unique position to consider the effect of multimorbidity in the context of the person’s individual circumstances and to tailor treatment recommendations to realistically attainable health care goals (Starfield, Reference Starfield2011). Moreover, primary care can increase equitable access to care and appropriate services, and reduce care costs with early community-based interventions that have the potential to prevent crises that lead to hospitalization (Starfield, Shi, & Macinko, Reference Starfield, Shi and Macinko2005).

Early recognition of frailty and its contributing conditions has been challenging because its manifestations can be subtle and slowly progressive, and thus dismissed as normal aging. Identification of frailty can ensure that treatment decisions consider the potential for worsened outcomes in the context of frailty, resulting in better-informed decision-making that is consistent with the individuals’ wishes and values. Recognition of co-existing conditions that are associated with frailty can optimize management, potentially avoiding health destabilization and related health care costs (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Heckman and Molnar2015). Several conceptualizations of frailty and multiple frailty scales have been proposed; however, there is a lack of consensus on how best to assess frailty in primary care practice (Abellan van Kan et al., Reference Abellan van Kan, Rolland, Houles, Gillette-Guyonnet, Soto and Vellas2010; Rodriguez-Manas et al., 2013). Although the Fried frailty phenotype measure has been extensively tested for its validity and is widely used in research (Bouillon et al., Reference Bouillon, Kivimaki, Hamer, Sabia, Fransson, Singh-Manoux and Batty2013; de Vries et al., Reference de Vries, Staal, van Ravensberg, Hobbelen, Olde Rikkert and Nijhuis-van der Sanden2011; Fried et al., Reference Fried, Tangen, Walston, Newman, Hirsch and Gottdiener2001), these measures may be too impractical or time-consuming to implement in busy clinical practice. The Centre for Family Medicine (CFFM) Family Health Team, in Kitchener, Ontario, Canada, created the CFFM Case-finding for Complex Chronic Conditions in Seniors 75+ (C5-75) program to meet the need for a feasible, efficient way to identify and address frailty within primary care.

The C5-75 Program

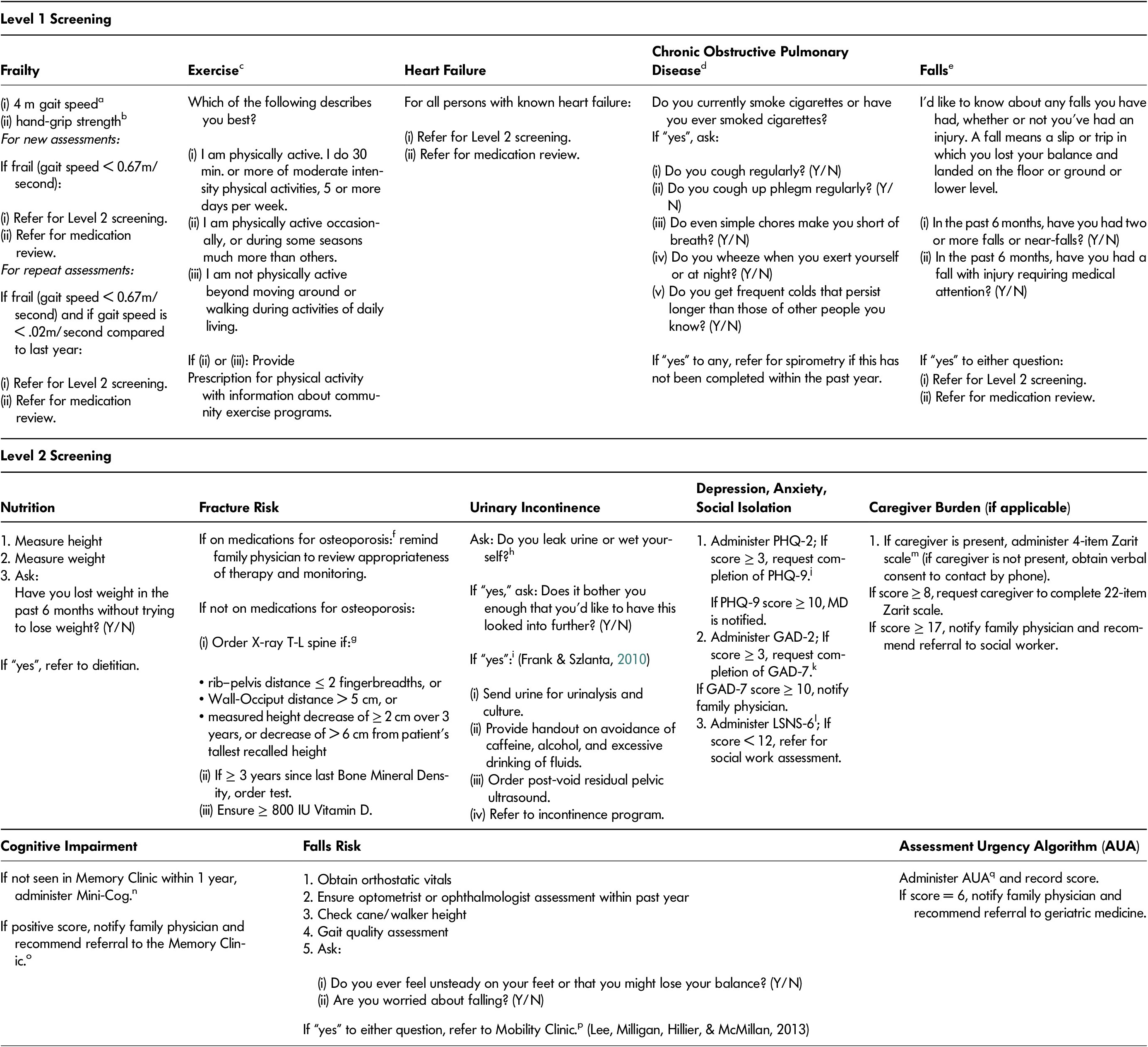

The C5-75 program is based on a chronic care model, a widely used framework for chronic disease management, which stratifies patients according to degree of risk and tailors interventions accordingly (Wagner, Austin, & von Korft, 1996). C5-75 aims to identify older adults who are frail and potentially at highest risk of poor outcomes and to initiate interventions to reduce the risk of health destabilization. The goal of C5-75 is to address frailty pro-actively in routine family practice to improve primary health care for older adults living with frailty, helping them to maintain health and well-being with the best quality of life for as long as possible. C5-75 incorporates a two-level algorithmic approach using validated tools. Level 1 annual screening consists of screening for frailty using a standardized assessment of gait speed and hand grip as well as low physical activity, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and falls. Level 2 screening systematically screens for common geriatric conditions associated with frailty, poor health outcomes, and risk for destabilization. The C5-75 screening protocol is presented in Table 1.

Table 1: Case-finding for Complex Chronic Conditions in Seniors 75+ (C5-75) screening tools

a Gait speed instructions: “Walk at your usual speed, as if you are walking down the street to go to the store. Walk all the way past the other end before you stop”.

b Hand grip measured twice on each side: “I would like to test your grip strength on both hands, as this can be an indicator of general strength. Squeeze as tightly as you can for 3 s”.

c Physical activity screening (Topolski et al., Reference Topolski, LoGerfo, Patrick, Williams, Walwick and Patrick2006)

d Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) screening (O’Donnell et al., Reference O’Donnell, Hernandez, Kaplan, Aaron, Bourbeau, Marciniuk and Voduc2008)

e Falls preventions (American Geriatric Society & British Geriatric Society, 2011)

f Medications for osteoporosis: risedronate; alendronate; denosumab; zolendronic acid; raloxifene; teriparatide

g Fracture prevention (Papaioannou et al., Reference Papaioannou, Morin, Cheung, Atkinson, Brown and Feldman2010)

h Urinary incontinence screening (Bettez et al., Reference Bettez, Tu, Carlson, Corcos, Gajewski, Jolivet and Bailly2012; Thuroff et al., Reference Thuroff, Abrams, Andersson, Artibani, Chapple and Drake2011)

i Management of urinary incontinence (Frank & Szlanta, Reference Frank and Szlanta2010)

j PHQ-2/PHQ-9: Patient Health Questionnaire (2- and 9-question versions) (Kroenke et al., Reference Kroenke, Spitzer and Williams2003; Kroenke & Spitzer, Reference Kroenke and Spitzer2002).

k GAD-3/GAD-7: General Anxiety Disorder (3 and 7 item versions) (Spitzer et al., Reference Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams and Lowe2006).

I LSNS: Lubben Social Network Scale (Lubben et al., Reference Lubben, Blozik, Gillmann, Iliffe, von Renteln Kruse, Beck and Stuck2006)

m Zarit Caregiver Burden Scale (Bedard et al., Reference Bedard, Molloy, Squire, Dubois, Lever and O’Donnell2001)

n Cognitive impairment screening (Borson et al., Reference Borson, Scanlan, Chen and Ganguli2003)

o Assessment and management of memory concerns (Lee et al., 2010)

p Assessment and management of mobility issues (Lee et al., 2013)

q Assessment Urgency Algorithm (Elliott et al., Reference Elliott, Gregg and Stolee2016)

Although the Fried frailty phenotype measure has been extensively tested for its validity (Bouillon et al., Reference Bouillon, Kivimaki, Hamer, Sabia, Fransson, Singh-Manoux and Batty2013; Di Baru et al., Reference Di Baru, Profili, Bandinelli, Salvioni, Mossello, Corridori and Francesconi2014; Saum et al., Reference Saum, Muller, Stegmaier, Hauer, Raum and Brenner2012) and is widely used in frailty research (Bouillon et al., Reference Bouillon, Kivimaki, Hamer, Sabia, Fransson, Singh-Manoux and Batty2013; Clegg, Rogers, & Young, Reference Clegg, Rogers and Young2015; de Vries et al., Reference de Vries, Staal, van Ravensberg, Hobbelen, Olde Rikkert and Nijhuis-van der Sanden2011; Pialoux, Goyard, & Lesourd, Reference Pialoux, Goyard and Lesourd2012), administration of these frailty measures is time-consuming and impractical within the context of clinical practice. Alternatively, single-trait measures of frailty such as gait speed alone may be more feasible to implement in practice; however, there is concern they may produce too many false positives (Clegg et al., Reference Clegg, Rogers and Young2015; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Patel, Costa, Bryce, Hillier, Slonim and Molnar2017).

In a previous study, we demonstrated that although single-trait measures of gait speed or hand grip strength alone were sensitive and specific proxies (sensitivity and specificity of 87.5%, 94.6% for gait speed; 100%, 90.5% for grip strength) for the Fried frailty phenotype, use of gait speed with grip strength was accurate, precise, specific, and more sensitive (sensitivity and specificity of 87.5%, 99.2%) than other possible combinations and were feasible to implement in primary care (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Patel, Costa, Bryce, Hillier, Slonim and Molnar2017). In this study, we found that the positive predictive value for single traits in predicting the Fried frailty phenotype ranged from 13 per cent to 53 per cent and increased to 88 per cent for the dual measure of gait speed and grip strength (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Patel, Costa, Bryce, Hillier, Slonim and Molnar2017). Measuring grip strength along with gait speed can increase screening predictive value without adding significant time, training, or costs (Bohannon, Bear-Lehman, Desrosiers, Massy-Westropp, & Mathiowetz, Reference Bohannon, Bear-Lehman, Desrosiers, Massy-Westropp and Mathiowetz2007; Karpman & Benzo, Reference Karpman and Benzo2014). Thus, we used the dual measure of gait speed and hand-grip strength as a proxy for the Fried frailty phenotype; this approach is a practical and efficient means of screening for frailty within primary care.

Those who screen positive for frailty in Level 1 or who have heart failure or a history of falls are then scheduled for Level 2 screening. Featuring standardized measures known to have good psychometric properties, Level 2 consists of screening for (a) nutrition, (b) fracture risk (Papaioannou et al., Reference Papaioannou, Morin, Cheung, Atkinson, Brown and Feldman2010), (c) urinary incontinence (Bettez et al., Reference Bettez, Tu, Carlson, Corcos, Gajewski, Jolivet and Bailly2012; Thuroff et al., Reference Thuroff, Abrams, Andersson, Artibani, Chapple and Drake2011; Uebersax, Wyman, Shumaker, McClish, & Fantl, Reference Uebersax, Wyman, Shumaker, McClish and Fantl1995), (d) depression (Kroenke & Spitzer, Reference Kroenke and Spitzer2002; Kroenke, Spitzer, & Williams, Reference Kroenke, Spitzer and Williams2003), (e) anxiety (Skapinakis, Reference Skapinakis2007; Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams, & Lowe, Reference Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams and Lowe2006), (f) social isolation (Lubben et al., Reference Lubben, Blozik, Gillmann, Iliffe, von Renteln Kruse, Beck and Stuck2006), (g) caregiver burden if applicable (Bachner & O’Rourke, Reference Bachner and O’Rourke2007; Bedard et al., Reference Bedard, Molloy, Squire, Dubois, Lever and O’Donnell2001), (h) cognitive impairment (Borson, Scanlan, Chen, & Ganguli, Reference Borson, Scanlan, Chen and Ganguli2003), (i) falls risk (American Geriatric Society & British Geriatric Society, 2011), and (j) risk for destabilization (Elliott, Gregg, & Stolee, Reference Elliott, Gregg and Stolee2016) (see Table 1).

Screening results are documented in the patient’s electronic medical record (EMR) and family physicians are notified when frailty or new conditions are identified. Evidence-informed interventions are then recommended, as applicable, for the management of these conditions, including referrals to other care providers (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Patel, Hillier, Locklin, Milligan, Pefanis and Boscart2018a). A team-based interprofessional approach enables physicians to identify and manage high-risk persons within primary care, addressing the challenges related to limited resources and limited physician time with the structure of a typically busy family practice. By bringing together the patient’s family physician, interprofessional health care providers, specialist physicians (if necessary), and community resources, health care providers are integrated within the primary care practice to meet patient and caregiver needs. More detailed information about the development and implementation of C5-75 and recommended interventions is available elsewhere (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Patel, Hillier, Locklin, Milligan, Pefanis and Boscart2018a).

The two-level screening process was developed to establish a feasible and efficient approach to screening for frailty in the context of a busy primary care setting. Completed by a nurse prior to regularly scheduled routine medical appointments, Level 1 screening takes approximately seven minutes to complete. Given the realities of busy family practice with hectic workflow and time and resource limitations, Level 2 screening is completed in a separate, dedicated appointment as conducted by nursing, pharmacy, and if applicable, social workers. It takes approximately 30 minutes to complete. We selected the screening tools and interventions implemented in the C5-75 program on the basis of current research evidence, best-practice guidelines, and expert opinion; we developed and trialled the screening protocol using an iterative process, consistent with Plan, Do, Study Act (PDSA) cycles (Gillam & Siriwardena, Reference Gillam and Siriwardena2013), of balancing potential benefits to patients with acceptability and feasibility within a busy clinical practice context (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Patel, Hillier, Locklin, Milligan, Pefanis and Boscart2018a).

In a previous study of 965 patients who completed the C5-75 Level 1 screening, we identified 7 per cent as frail on the basis of their gait speed and grip strength; Level 2 screening (n = 640) identified patients with cognitive impairment (22%), depression (7%), social isolation (20%), and urinary incontinence (39%) (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Patel, Hillier, Locklin, Milligan, Pefanis and Boscart2018a). An examination of 499 screenings for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) resulted in 11 patients being referred for spirometry, after which four were newly diagnosed with COPD (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Patel, Hillier and Milligan2016). We have also demonstrated the feasibility and acceptability of this program within our family practice setting as well as in a less-resourced group of 14 family practices in collaboration with a community pharmacy Lee et al., Reference Lee, Locklin, Skimson and Patel2018b). Although described as a valuable way to pro-actively identify frailty and health issues, integrating C5-75 into busy family practice can be challenging from both a time and resource perspective, even at Level 1, which is quite brief (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Lu, Hillier, Bedirian, Skimson and Milligan2019).

After having implemented the C5-75 program for five years, we were interested in increasing the efficiency of the C5-75 workflow by targeting the program to those who are most likely to be frail. The purpose of this study was to identify which C5-75 screening criteria best identify those who are frail. With this information, we streamlined the screening process. A second objective was to report the prevalence of frailty as assessed by the new screening process.

Methods

Study Design

We conducted a retrospective medical record review for all consecutive patients assessed in the C5-75 program between April 1, 2014, and December 12, 2018. This study was approved by the Hamilton Integrated Research Ethics Board, McMasterUniversity.

Setting and Participants

Participants were patients who completed the C5-75 screening within the CFFM Family Health Team, which consists of interprofessional health care providers (physicians, nurses, social workers, and pharmacists) serving 28,420 patients, 1,518 of whom were aged 75 years and older, across 19 urban and rural family physician practices.

C5-75 Screening Process

Prior to regularly scheduled routine medical appointments, all patients 75 years and older completed the C5-75 assessment, as administered by specially trained nurses. Patients were excluded from screening if they were acutely ill; participation was voluntary. Frailty was measured using gait speed (Abellan van Kan et al., Reference Abellan van Kan, Rolland, Andrieu, Bauer, Beauchet, Bonnefoy and Vellas2009), calculated as the number of seconds to walk four metres at a usual pace (the fastest of two trials is recorded), and hand grip strength (Syddall, Cooper, Martin, Briggs, & Aihie, Reference Syddall, Cooper, Martin, Briggs and Aihie2003), calculated as the higher score of two 3-second trials, with each hand, using a handheld dynamometer (Jaymar Hydraulic Dynamometer Model #281-12-0600, J.A. Preston Corp, Clifton, NJ). Frailty was defined as four-meter gait speed of greater than 6 seconds (Abellan van Kan et al., Reference Abellan van Kan, Rolland, Andrieu, Bauer, Beauchet, Bonnefoy and Vellas2009). Hand grip weakness was defined as a score within the lowest 20 per cent of the population, and stratified by gender (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Patel, Costa, Bryce, Hillier, Slonim and Molnar2017; Leong et al., Reference Leong, Teo, Rangarajan, Lopez-Jaramillo, Avezum and Orlandini2015). We validated this dual-trait frailty measure in previous research to be an accurate, precise, sensitive, and specific proxy for the Fried frailty phenotype (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Patel, Costa, Bryce, Hillier, Slonim and Molnar2017).

Patients were also screened for level of self-reported physical activity (Topolski et al., Reference Topolski, LoGerfo, Patrick, Williams, Walwick and Patrick2006), history of falls (American Geriatric Society & British Geriatric Society, 2011), and COPD for those with a smoking history (O’Donnell et al., Reference O’Donnell, Hernandez, Kaplan, Aaron, Bourbeau, Marciniuk and Voduc2008) (Table 1). Patients identified as frail, as well as those who had heart failure and a history of falls (two or more in six months, or any falls requiring medical attention in six months) were scheduled for Level 2 screening and were referred to a pharmacist for medication review to identify medication-related problems and ensure medication optimization.

Data Collection and Analyses

Descriptive Statistics and Yield Calculations.

Data collected from medical records included patient age, gender, and all assessment results. We conducted statistical analyses using R v3.5.2 (R Core Team, 2013). Descriptive statistics (frequencies, means, standard deviations) were generated for age, gender, frailty measures, and positive screening results (categorical items). We defined dual-trait frailty as gait speed < 0.67m/second in addition to a grip strength of less than 14 kg/m2 for females or 24 kg/m2 for males. We defined item yield as the proportion of assessments in which an item was answered positively, unless that figure was greater than 50 per cent in which case the yield was one minus the positive proportion. This reflected the concept that an item that is consistently answered the same way (positive or negative) tends to contain less information than an item with greater balance between positive and negative responses. We calculated yield for the categorical items on the Level 1 and Level 2 assessments. For items with more than two possible responses, to calculate yield we used the most prevalent response against the other responses.

Associations with Frailty.

For statistical analysis, we randomly split the data set into a training set containing 70 per cent of the cases and a validation set containing the remaining 30 per cent. We examined the associations between Level 1 assessment items and frailty defined by dual trait or gait speed alone, as measured on the same assessment within the training data set. We used multivariable logistic regression with generalized estimating equations and robust covariance estimation to account for correlation between multiple assessments belonging to the same patient. Missing data were treated with multiple imputation (van Buuren, Reference van Buuren2007).

Optimization.

In order to optimize the C5-75 assessment process, assessment items considered to have little value were identified for removal. Decisions regarding item removal were determined by team discussions considering item yield, strength of association with frailty, and the clinical importance of the item as judged by the group.

Criteria Development.

We examined items retained on the C5-75 Level 1 assessment that had significant associations with frailty to determine whether criteria could be developed to exclude patients with a very low likelihood of frailty from gait speed and hand-grip measuring. Various criteria combining Level 1 items were examined and evaluated for their sensitivity, negative predictive value, and size using the validation data set. We determined a priori that an exemption protocol would need to achieve at least 90 per cent, preferably 95 per cent, sensitivity for dual-trait frailty.

Results

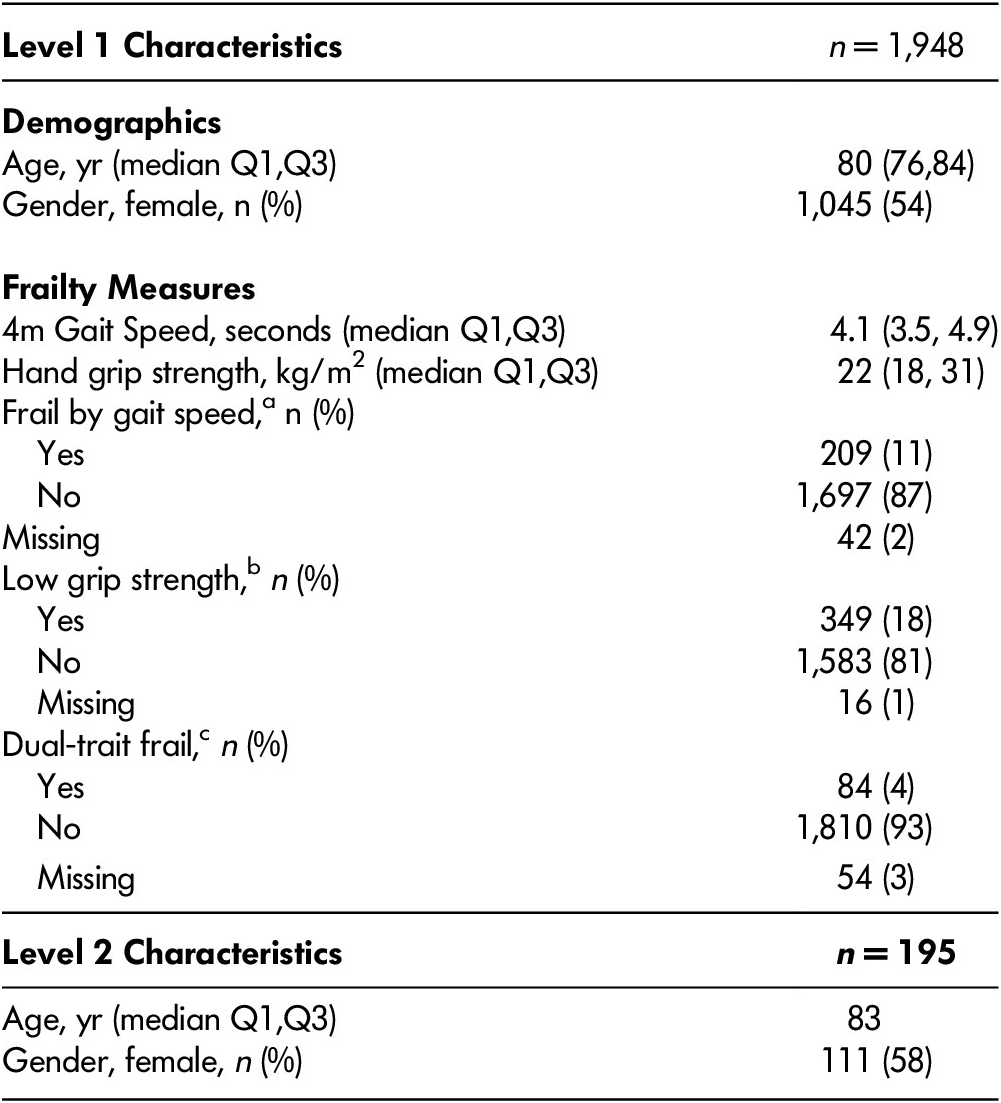

A total of 1,948 Level 1 assessments were completed by 1,123 patients; 507 patients had at least two Level 1 assessments completed over time. There were 195 Level 2 assessments completed by 159 patients; 23 patients had at least two Level 2 assessments. Patients contributing to Level 1 assessments to the study had a median age of 80, and 54 per cent were female (Table 2). There were 209 patients (11%) considered to be frail by gait speed, 349 patients (18%) had low grip strength, and 84 patients (4%) met the criteria for dual-trait frailty.

Table 2: Level 1 and 2 sample characteristics

Q1 = 1st quartile; Q3 = 3rd quartile

a 4m gait speed < 6 seconds

b Hand grip strength < 14 for females, or < 24 for males

c Both fail by gait speed and low grip strength

Item Yields

Levels 1 and 2 screening results are presented in Supplementary Table S1. Yields for the Level 1 assessment items ranged from 1.2 per cent to 48.1 per cent. The lowest yielding items were colds persist longer (1.2%) and wheeze during exertion (3.6%); the highest yielding item was regular physical activity (48.1%) and history of smoking (43.8%). Yields for the Level 2 assessment items ranged from 0.5 per cent to 27.8 per cent (Supplementary Figure S1). The lowest yielding items were weight loss greater than 5 lbs. (4.2%), self-reported fracture in previous year (6.0%), and a positive screen for generalized anxiety disorder (9.3%). The highest yielding items were self-reported urinary incontinence (36.3%), more than one fall in past year (27.8%), and a positive screen for cognitive impairment (25.6%).

Associations with Frailty

Older age in years (OR: 1.21, 95% CI, 1.13, 1.30), more than two falls in six months (OR: 3.36, 95% CI 1.18, 9.57), exercise only with daily living activities (OR: 8.54, 95% CI 2.74, 26.65), and only occasional exercise (OR: 2.94, 95% CI 1.11, 7.73) were factors significantly associated with dual-trait frailty (Table 3). Associations with gait-only frailty were similar: older age in years (OR: 1.14, 95% CI 1.09, 1.20), more than two falls in six months (OR: 4.35, 95% CI 2.00, 9.46), exercise only with daily living activities (OR: 9.66, 95% CI 5.09, 11.83), and only occasional exercise (OR: 3.34, 95% CI 1.83, 6.14).

Table 3: Odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) from multivariable logistic regression of dual-trait frailty and gait speed frailty

Screening Criteria

We developed exemption protocol criteria using various combinations of age, falls history, and self-reported activity levels. Two criteria met the 95 per cent sensitivity threshold for both dual-trait frailty and gait-only frailty. A protocol that would exempt patients under 80 years of age who reported regular physical activity exempted 25.7 per cent of patients in our sample. These criteria had a sensitivity of 98 per cent and negative predictive value of 99.6 per cent for dual-trait frailty and a sensitivity of 97.7 per cent and negative predictive value of 99 per cent for gait frailty (Table 4). A second potential exemption protocol would exempt patients under 85 years old who reported regular physical activity and fewer than two falls in the past six months; this exempted 39.1 per cent of patients in our sample with a sensitivity of 95.2 per cent and negative predictive value of 99.4 per cent for dual-trait frailty, and a sensitivity of 96 per cent and negative predictive value of 98.9 per cent for gait frailty (Table 4). None of the criteria examined achieved 90 per cent sensitivity for low grip strength (Supplementary Table S2).

Table 4: Prevalence of frailty and diagnostic accuracy measures of exemption criteria for dual-trait frailty and gait frailty on validation sample

PPV = Positive predictive value; NPV = Negative predictive value

Discussion

This study revealed that age (85 years and older), less than regular physical activity, and more than two falls in the past six months had the strongest associations with frailty. These findings support the increasing recognition of the association between physical activity and frailty, both in terms of low physical activity being a risk factor for frailty, and increasing evidence to support the effectiveness of physical activity interventions for frail older adults (Kehler et al., Reference Kehler, Hay, Stammers, Hamm, Kimber, Schultz and Duhamel2018; Negm et al., Reference Negm, Kennedy, Thabane, Veroniki, Adachi, Richardson and Papaioannou2017; Rogers et al., Reference Rogers, Marshall, Roberts, Demakakos, Steptoe and Scholes2017). The identification of screening items most strongly associated with frailty provides insight into how to more optimally and efficiently identify frailty in primary care to achieve maximum positive yield with minimum resource use. Revisions to the screening process (Figure1) focused on streamlining Level 1; we retained physical activity and falls items on the basis of their associations with frailty and removed screening for COPD; we also retained history of heart failure as a criterion for Level 2 screening for its clinical relevance. COPD screening was replaced with screening for dyspnea in Level 2 to identify poorly managed cardiorespiratory conditions (Fletcher, Reference Fletcher1960); focusing on this in Level 2 may have increased its yield as the focus here was on screening among frail adults. We replaced nutrition screening in Level 2 with a new tool to screen for malnutrition (Morrison, Laur, & Keller, Reference Morrison, Laur and Keller2019). Lastly, we eliminated shortened versions of the depression (Kroenke et al., Reference Kroenke, Spitzer and Williams2003) and anxiety (Skapinakis, Reference Skapinakis2007) screening tools to reduce assessment burden of having to administer both the shorter and longer versions of the tools.

By retaining the highest yield/most clinically important elements and eliminating the rest, we can make this program more feasible and generalizable to other primary care practice sites, which will likely impact longer-term sustainability. Feasibility is particularly relevant for Level 1 screening where there is a need to keep negative impact on patient flow in a busy practice setting to a minimum; this is less relevant for Level 2, which is completed in a separate office visit. As increasing age is strongly associated with frailty, it may not be necessary to screen all persons under age 85 for primary care for frailty; using hand-grip strength and gait speed on just those over age 85 or those over age 75 who report two or more falls in the past six months or report exercising only with activities of daily living (6% of patients) will capture almost the same number of frail persons as would be achieved by screening all patients aged 75 years and older. By targeting more comprehensive Level 2 interventions for only those most in need – that is, those who are frail – those complex conditions which can worsen frailty or be worsened by frailty can be identified and managed pro-actively to prevent destabilization of health.

This study confirms screening differences based on whether frailty is determined based on gait speed alone or dual traits (gait speed and hand grip). Other researchers have also noted that different ways of screening for frailty yields different subsets of frail patients; one method is not necessarily “better” than the other but, rather, they are complementary methods (Cesari, Gambassi, van Kan, & Vellas, 2014). Our findings confirm this emerging concept that gait speed alone will identify a slightly different population of frail persons than those identified by gait speed and hand-grip strength. Depending on resources available, physicians in primary care settings may elect to define frailty on the basis of gait speed alone; however, in doing so they will need to be aware that they may be identifying persons with differing prevalence of certain co-morbidities and may also be generating more false positives (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Patel, Costa, Bryce, Hillier, Slonim and Molnar2017). The findings from this study provide additional support for our previous study finding that dual-trait frailty (hand-grip strength and gait speed) is preferable to single-trait measures alone (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Patel, Costa, Bryce, Hillier, Slonim and Molnar2017) if the aim is to efficiently identify within primary care practice those older adults who are frail and have associated but unrecognized conditions which co-exist and may worsen frailty or be worsened by frailty.

Focusing on Level 1 items for primary care allows for the stratification of patients based on the risk of poor outcomes and tailoring intensity of intervention accordingly. Consistent with a chronic disease care model (Scott, Reference Scott2008), all patients aged 75 years and older would receive a simple, quick, high-yield systematic screening process that is feasible at the primary care level to detect frailty; those deemed frail (and at higher risk of poor outcomes) would receive a more intense case finding for conditions associated with frailty. The rationale for this type of screening in primary care is the opportunity to optimize the management of these often unrecognized, co-morbid conditions before they destabilize. This upstream approach aims to prevent acute care utilization associated with destabilized conditions such as falls, medication mismanagement due to unrecognized dementia, fracture due to poorly managed osteoporosis, or unrecognized caregiver stress.

Key strengths of this program, which differentiate it from other frailty tools, are that it is (a) quick, practical, objective, and measurable; (b) created by primary care practitioners for busy primary care practice and validated in a family practice population; (c) systematically implemented into regular primary care office visits using typical office staff and is not dependent on physician time for screening; (d) not dependent on accurate updated EMR records on each patient, which is sometimes challenging when diagnoses are not recorded or no longer current and medication lists may be outdated; (e) not dependent on knowledge of functional abilities, which may be inaccurate when based on self-report and may require corroborated history for verification, nor is it dependent on a comprehensive geriatric assessment in order to determine level of frailty; and (f) it is based on the Fried frailty phenotype concept of frailty, which is one of the most commonly used standards of frailty in the published literature (Bouillon et al., Reference Bouillon, Kivimaki, Hamer, Sabia, Fransson, Singh-Manoux and Batty2013; de Vries et al., Reference de Vries, Staal, van Ravensberg, Hobbelen, Olde Rikkert and Nijhuis-van der Sanden2011).

Limitations and Future Research

Completion of C5-75 screening is limited to those who have scheduled primary care appointments and excludes those who are housebound and might be the frailest of patients. As such, this selection bias may underestimate the prevalence of frailty in this practice setting. Screening for falls in this study is based on self-report, which may underestimate the true prevalence of falls (Ganz, Higashi, & Rubenstein, Reference Ganz, Higashi and Rubenstein2005; Mackenzie, Byles, & D’Este, Reference Mackenzie, Byles and D’Este2006; Peel, Reference Peel2000). However, the objective of the screening program is not to accurately estimate the prevalence of falls, but rather to identify patients at high risk for frailty. So, while the number of falls might be underreported, our study demonstrates a strong association between the self-report of two or more falls in six months and frailty, which justifies its use in the screening protocol.

Although this study was implemented in a multidisciplinary primary care setting, with human resources and processes in common with other primary care–based programs for older adults (Counsell et al., Reference Counsell, Callahan, Clark, Tu, Buttar, Stump and Ricketts2007), more research is needed on the feasibility and impacts of implementation of C5-75 within varying practice models. We are currently examining the relationship between the trajectory of frailty and co-morbid conditions and interventions provided. Pilot testing of the revised screening protocol – with consideration for feasibility, acceptability to health care providers and patients, and efficiency – will further support improvements to this program. Of particular interest will be evaluative studies of the impact of C5-75 in enabling primary care to better identify and manage older adults living with frailty and streamlining referrals to geriatric medicine specialists, similar to other programs that build capacity in primary care for the management of complex geriatric conditions and improve efficiency of use of limited available specialist resources (Lee et al., 2010; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Hillier, McKinnon, Gregg, Fathi, Sturdy Smith and Smith2018c).

Within the Level 1 screening protocol, we considered an individual’s ever having had a diagnosis of heart failure as being an indication for referral to Level 2 screening. The idea was that anyone who has ever had heart failure may benefit from medication optimization and pro-active identification as well as management of possible co-existing conditions, such as cognitive impairment and falls risk, to reduce risk of health destabilization. In considering heart failure, we did not use criteria for staging cut-offs, but it is possible that considering stage of heart failure may further increase efficiency of this inclusion criteria. This is an area for future exploration as we analyse data to determine the yield of referring all persons ever diagnosed with heart failure.

Conclusions

The findings from this study generated a more optimized, two-step screening process which uses annual hand grip and gait speed screening for frailty for patients aged 85 years and older, as well as for those aged 75 years and older who reported two or more falls in the past six months or who reported exercising only with activities of daily living. This screening process will identify approximately the same number of frail persons as would be identified by screening every person aged 75 and older. This approach will make it more feasible to routinely screen for frailty in primary care setting to optimize primary health care for older adults living with frailty, as well as to support informed treatment and care decisions in the context of frailty.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0714980820000161.