Introduction

Conversations about public services in Canada often include long-term residential care in questions about the appropriate allocation of public funding. Long-term residential care (LTRC) facilitiesFootnote 1 offer around-the-clock care and supervision for persons with diverse health needs, although in the current context, residents are predominantly of advanced age and living with dementia. The most recent Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) report notes that among those facilities reporting data, the average age of residents is 83 years, and 61.6 per cent have a diagnosis of dementia (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2017). Operating on a mixed private–public model across the provinces and territories, LTRC facilities (known as personal care homes [PCHs] in Manitoba) have increasingly become the focus of political and media inquiries regarding the role and quality of services supported by public resources. Given the current dialogue around the allocation of public funding to care services, it is timely to investigate societal narratives of the role(s) that LTRCs play as sites of living, working, aging, and dying, and how these narratives intersect with cultural ideas about necessary public spaces and services in Canada. This study was completed prior to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, which has amplified pre-existing narratives and tensions in cultural expectations of LTRC. In delineating the complex social roles of LTRC prior to the pandemic, our hope is that this investigation offers opportune insights towards efforts to understand how social narratives of LTRC evolve during this time.

Public representations of LTRC have received limited focus in Canada, although we have some knowledge from other countries that public perceptions of these spaces tend to be overwhelmingly negative, particularly in health care contexts that prioritize aging and dying in place (Henderson & Vesperi, Reference Henderson and Vesperi1995; Hockley, Harrison, Watson, Randall, & Murray, Reference Hockley, Harrison, Watson, Randall and Murray2017; Miller, Tyler, Rozanova, & Mor, Reference Miller, Tyler, Rozanova and Mor2012). In fact, the setting itself has been identified as stigmatizing (Dobbs et al., Reference Dobbs, Eckert, Rubinstein, Keimig, Clark and Frankowski2008), with critical gerontologists citing these spaces as of the “fourth age” (Higgs & Gilleard, Reference Higgs and Gilleard2015) and others likening them to the symbolic interactionist concept of the “total institution” (Goffman, Reference Goffman1961). In Australia, for example, LTRC facilities are depicted in mainstream media as negative, particularly in contrast to commercial retirement villages, where residents are depicted as “normal” in contrast to the “other”, needing more care in nursing homes (Kirkman, Reference Kirkman2006). In the United States, Miller et al. (Reference Miller, Tyler, Rozanova and Mor2012) drew a similar conclusion and noted that national newspaper coverage of nursing homes tended to focus on government and industry interests rather than on the concerns of residents, families, or communities.

Although LTRC settings are places of residence and medical care, they are also places of employment, hence their role in society implicates not only those who live there, but also those who work there. Research on the experiences of LTRC staff highlights the organizational complexities within which staff must fulfill their professional responsibilities. A substantial body of literature documents LTRC staff experiences of physical risk in the workplace, and outlines organizational strategies to manage the risk of violence and injury (e.g., Evanoff, Wolf, Aton, Canos, & Collins, Reference Evanoff, Wolf, Aton, Canos and Collins2003; Gillespie et al., Reference Gillespie, Gates, Miller and Howard2010; Wagner, Capezuti, & Rice, Reference Wagner, Capezuti and Rice2009). Complementing this literature is research demonstrating the high levels of burnout in LTRC staff, such as a study by Woodhead, Northrop, and Edelstein (Reference Woodhead, Northrop and Edelstein2016), who demonstrate that greater occupational stress among LTRC nursing staff was associated with greater emotional exhaustion and a sense of depersonalization.

Constructions of the role(s) of LTRC facilities are intertwined with narratives about those who reside (and work) there, and are particularly influenced by social discourses around aging and dementia. Taking into consideration the negative discourses around aging (Kenyon, Reference Kenyon1992; Orešković, Reference Orešković2020) and dementia as experiences closely associated with the use of long-term care, the negative depictions of these facilities seems unsurprising. In scholarly, professional, and popular literature, as well as in mainstream news media accounts across Western countries, older persons living with dementia are portrayed in various stigmatizing, dehumanizing, and reductionist ways in what has been called a “discourse of violence” (Mitchell, Dupuis, & Kontos, Reference Mitchell, Dupuis and Kontos2013). Research examining such material in the United Kingdom (Behuniak, Reference Behuniak2011; Brookes, Harvey, Chadborn, & Dening, Reference Brookes, Harvey, Chadborn and Dening2018; Latimer, Reference Latimer2018; Peel, Reference Peel2014), Canada (Funk, Herron, Spencer, & Thomas, Reference Funk, Herron, Spencer and Thomas2021); Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell, Dupuis and Kontos2013); Australia (Doyle, Reference Doyle2012; Kirkman, Reference Kirkman2006), Belgium (Gorp & Vercruysse, Reference Gorp and Vercruysse2012), and Norway (Siiner, Reference Siiner2019) points to the use of language that is objectifying, paternalistic, and fear inducing. The hegemonic construction of dementia appeals to the modern emphasis on management of control, reinforcing the dehumanization of persons living with dementia (Mitchell, Dupuis, Kontos, Jonas-Simpson, & Gray, Reference Mitchell, Dupuis, Kontos, Jonas-Simpson and Gray2020).

Latimer (Reference Latimer2018) indicates that these stigmatizing and dehumanizing depictions serve as “the background against which dominant versions of what it is to age well are being performed” (p. 834), and Peel (Reference Peel2014) identified the emergence of a newer narrative implying individual responsibility for preventing one’s own dementia. Private responsibility, the idea that social (and physical) wellness is in the realm of individuals and is in fact their responsibility, rather than in the realm of public institutions, is a notion associated with the ideology of neoliberalism (Ilcan, Reference Ilcan2009). Although there is no single definition of the term (Gard, Reference Gard, Lewis and Potter2011), here we use the term “neoliberalism” to encompass the interconnected set of beliefs, practices, and policies that promotes free trade, market competition, privatization, and the erosion of government intervention in social welfare. Although it is closely tied to broader international and global political and economic processes, the cultural and material processes of neoliberalism and their effects can also be observed at regional and even individual levels in our analysis.

Aging in place initiatives, adopted by health authorities across Canada, are grounded in the assumption that people want to grow old in the spaces where they normally reside (Funk, Reference Funk2013). The narrative of “aging in place” positions aging as an experience that is also properly relegated to the private space of the “home”. Evidence shows that the experience of “community” is complex for older people, especially in the age of globalization where there are greater opportunities as well as barriers for individuals to choose the place where they age (Phillipson, Reference Phillipson2007). This narrative positions the family as an invisible force in making this possible, and positions those whose needs cannot be met at home and by invisible or undervalued caregivers as a problem, because their needs exceed the limits of the social contract of neoliberalism: namely that each individual should be responsible for him- or herself. If aging is a problem, then the course of action reflected within neoliberalism is to hold each person and their family responsible for addressing aging using their private resources (their own home as a residence; their family as individual caregivers). What happens when these private resources are insufficient to contain the experience of aging? This leads to “public aging”, wherein older people leave their homes in the hope of accessing public resources (in this case, in semi-public spaces) to meet their care needs (Wise, Reference Wise2002).

The problematization of older people who access LTRC in this way influences how long-term care itself is portrayed in public discourse. Using critical discourse analysis (CDA), Siiner (Reference Siiner2019) focuses on uncovering power relations behind language, to conclude that in Norwegian media, “dementia discourse depicts persons with dementia and their families only to a minimal extent as individuals in charge of their own situation. By depicting them as belonging to a generic group, it is not easy for the reader to feel empathy with them… collectivisation is used as a dehumanising tool” (p. 987). Siiner (Reference Siiner2019) observes that despite some shifts in media coverage towards greater recognition of personhood, there is a continued emphasis on institutional authorities/experts and a tendency to portray persons living with dementia as lacking control or agency. The dehumanization of persons with dementia presents a double burden for those who are already marginalized. In one case study of news media coverage of a specific incident in Canada, MacLeod (Reference MacLeod, Hulko, Wilson and Balestrery2019) highlights additional inequities in terms of how Indigenous older adults with dementia are portrayed in a more criminalized way compared with others.

More recently, and in Canada, Struthers (Reference Struthers, Chivers and Kriebernegg2017) explores policy and media narratives of care homes in Ontario from post-World War II to the present day, documenting historical shifts around the 1990s to a greater emphasis on costs of population aging, an “audit culture”, and an emphasis on medical over social care. Struthers (Reference Struthers, Chivers and Kriebernegg2017) emphasizes:

Few institutions have been surrounded by as much confusion, such gendered contradictions, and so many cultural anxieties as care homes for older adults, which bear the weight of cultural and economic uncertainties around population aging, changing perceptions of frailty and family ties, the meaning of dependence and independence, and fears of mortality (p. 283).

Lastly, an international comparison of nursing home media scandals in five countries, including Canada (Lloyd, Reference Lloyd2014), highlights how such scandals can influence public perceptions, and connects the scandals to the expansion of for-profit care provision and investigative reporting. Lloyd (Reference Lloyd2014) examines how journalists drew public attention to a coroner’s investigation into one Canadian case in British Columbia (i.e., the death of Eldon Mooney) which in part stimulated the Senior’s Action Plan in that province and creation of the Senior’s Advocate. Two recent instances reinforce Lloyd’s (Reference Lloyd2014) findings that scandals highlight “a lack of consensus around the role of the state in the delivery of residential care” (p. 2). The first is the case of Elizabeth Wettlaufer, a nurse who was convicted in 2017 of killing eight seniors over the span of a decade (Gillese, Reference Gillese2019). Her case led to the commissioning of The Long-Term Care Homes Public Inquiry, which resulted in a highly publicized report (Gillese, Reference Gillese2019) pointing to the large ratio of patient to staff in the facilities where Wettlaufer worked, and that her colleagues had expressed concerns as early as 2012. More recently and during the COVID-19 pandemic, the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) were deployed to support staffing at affected LTRC facilities in Ontario, and subsequently released a report (Mialkowski, Reference Mialkowski2020) illustrating the poor diet and hygiene experienced by residents in the facilities most affected by the pandemic. Both the Wettlaufer case and the CAF report jolted news media coverage of public opinion in response to these scandals, with the narrative focusing on a general lack of consensus over the degree of public responsibility for addressing the perceived gaps in LTRC services.

The work of Struthers (Reference Struthers, Chivers and Kriebernegg2017) in Ontario represents an important building block for the present study, which engages a CDA of LTRC policies for what are known, in Manitoba, as PCHs. Here, we extend analytic attention beyond policy and media to include a broad base of public materials including legislation, public Web sites, mission statements, and reports.The purpose of this study is to examine current narratives and publicly available interpretations of the role and function of PCHs, and to understand these in the context of a changing care system. Specifically, we ask: What particular understandings of the role and purpose of LTRC manifest in public and policy discourses about PCHs? Manitoba is taken as a case study to address this question. In this province, provincial political shifts over the past decade have created opportune conditions for public conversations about the role(s) and functions of PCHs, within the larger social context and in relation to existing structures of health and aging.

In Manitoba, 125 PCHs (Government of Manitoba, 2018) support approximately 12 per cent of Manitobans over the age of 75 (˜ 5,700 persons), providing a form of publicly funded, facility-based care with 24-hour supervision. Costs are partly subsidized by the provincial government, but residents pay a monthly means-tested fee. In Manitoba, approximately 13 per cent of PCHs have for-profit ownership, compared with a national average of 28 per cent (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2020). As in other provinces, PCH care is not federally insured under the Canada Health Act. Standards are dictated by provincial legislation and accreditation requirements. Most of the work is performed by unregulated health care aides; in urban Manitoba, more than 70 per cent of these care aides are born outside of Canada (Estabrooks, Squires, Carleton, Cummings, & Norton, Reference Estabrooks, Squires, Carleton, Cummings and Norton2015), and they tend to be employed on a casual or part-time basis (Novek, Reference Novek2013).

Manitoba has one of the highest rates of PCH beds per 1,000 population (Manitoba Nurses’ Union, 2006; Menec, MacWilliam, Soodeen, & Mitchell, Reference Menec, MacWilliam, Soodeen and Mitchell2002). In the past decade, calls for increasing the number of PCH beds in response to the province’s aging population have run parallel to significant cuts to public health and social services (Camfield, Reference Camfield, Evans and Fanelli2018). Despite increases in the acuity of residents admitted into PCHs, funding and staffing ratios have remained unchanged since the 1970s (Manitoba Nurses’ Union, 2018). This reflects similar challenges faced by long-term residential care providers across the country, as the aging population and pressures towards hospital discharge create increased need for PCH services, while resourcing has not kept pace with demand. Therefore, the nature of the work done by PCH services has shifted towards only the most basic tasks (Lowndes & Struthers, Reference Lowndes and Struthers2016), leaving the bulk of care to the responsibility of family caregivers and volunteers, paid companions, and family members to provide social, recreational, and emotional “extra’s”; Barken, Daly, & Armstrong, Reference Barken, Daly and Armstrong2016; Funk & Outcalt, Reference Funk and Outcalt2020; Funk & Rogers, Reference Funk and Roger2017). Using Manitoba as the study context, we investigate a question of broad relevance to the Canadian context, specifically: what are current public perceptions of the role and function of long-term care in the context of a changing health care system?

Methods

This analysis focuses on how the roles and functions of PCHs are constructed in social discourse in Manitoba; to that end, we used CDA as our methodological approach. Fairclough (Reference Fairclough2015) defines discourse as “language in its relations with other elements in the social process” (p. 8). Discourse is “both determined by social structure and contributes to stabilizing and changing that structure simultaneously” (Wodak & Meyer, Reference Wodak, Meyer, Wodak and Meyer2009, p. 7), meaning that language not only reproduces social structures, but can also be instrumental in altering them. CDA is different from more “generic” discourse analysis by its focus on power within social structures.

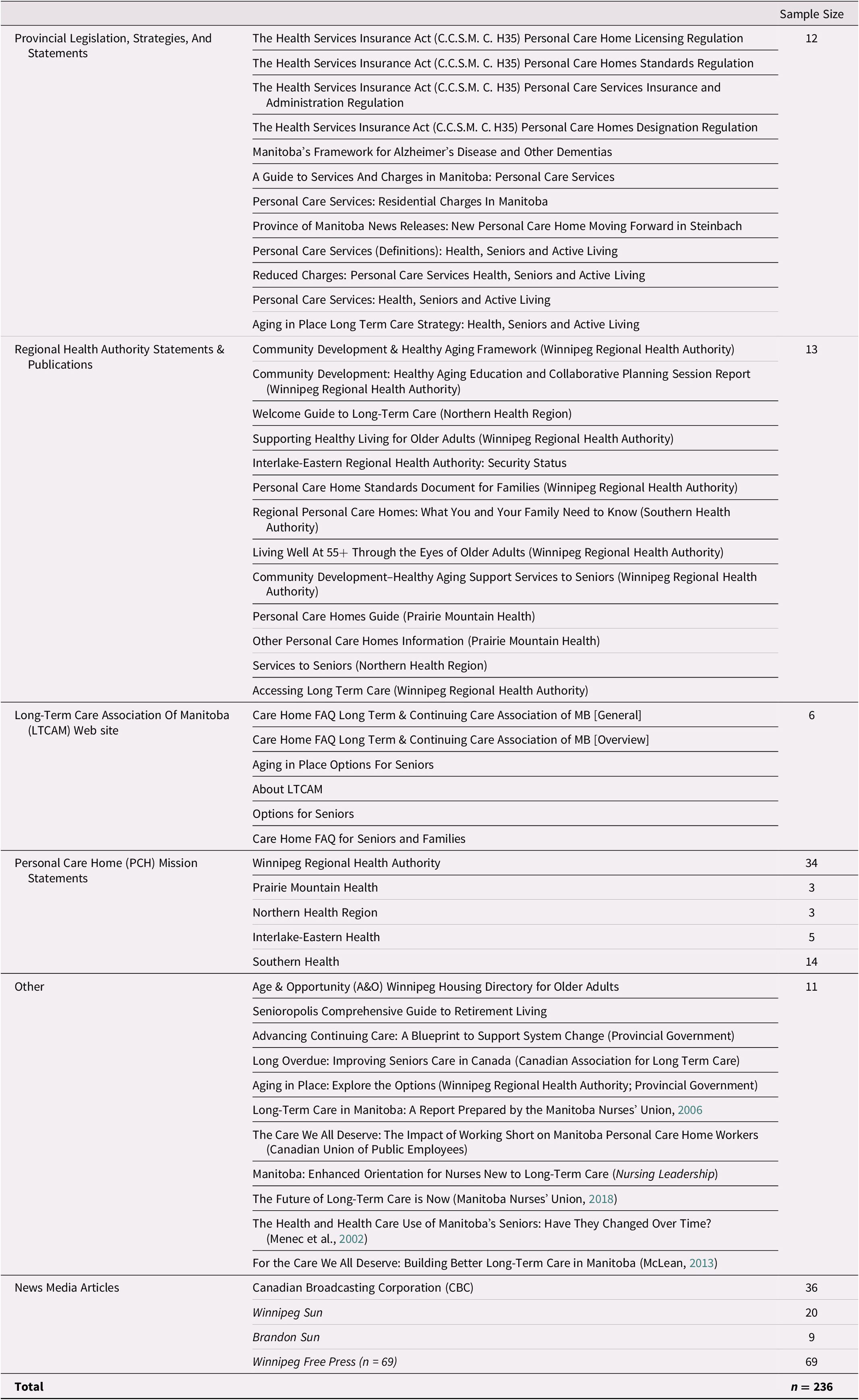

To explore how the roles and functions of PCHs are portrayed in Manitoba, we examined the language used by various sources that contribute to the discourse around PCHs. Using strategic sampling guided by our research question, whereby documents were only included if they addressed one or more concepts addressed by the research question, and including only English language texts published between 2009 and 2019 (prior to the COVID-19 pandemic), we included the following: legislation and official provincial strategies (n = 13), regional health authority publications and information for the public (print and digital formats; n = 13), PCH mission statements (n= 50); the Long Term and Continuing Care Association of Manitoba (LTCCAM) Web site, union reports, and other relevant publications such as policy documents and government reports (n= 17) (see Table 1). Additionally, we included provincial English-language mainstream news media coverage published within the last 5 years, from the following news media outlets: Winnipeg Free Press, Winnipeg Sun, CBC Manitoba, and the Brandon Sun.

Table 1. Categories and names of documents analyzed

CDA is more than a method of analysis. It is an interpretive approach that does not necessarily prescribe an analytic process; rather, it emphasizes not only what the text says but also how it says it. This includes a consideration of the tone, symbolism, and connotations of the text while interpreting the information conveyed through its language. As such, we approached our analysis by drawing on Fairclough’s (Reference Fairclough2015) recommended steps for beginning CDA with a dissection of language structures, then moving to interpreting their function and the discourses they reproduce and/or challenge. We used a multi-step approach that consisted of:

-

1. Preliminary reading of the texts, coding patterns of language usage (e.g., common or co-occuring terminology or styles of phrasing) and writing researcher memoranda

-

2. Secondary reading of the texts, with particular attention paid to the manifest and latent meanings (content) of the language used as well as how these meanings are positioned relative to each other and to actors/stakeholders/social structures

-

3. Interpretive dialogue among team members whereby we drew connections between patterns observed in the data and our personal or professional knowledge of PCHs and social structures in Manitoba

The first two steps of analysis for the various public documents and mission statements were completed by one coder, who had currently completed a Master’s degree using discourse analysis (R.E.B.), after which the leading team members for Phase 1 (G.T., L.F., R.E.B., M.S.) collaborated on the third step of the analysis. The news media sources were analyzed by four coders (G.T., L.F., R.E.B., M.S.), who completed steps 1 and 2 of the analysis separately, then collaboratively completed step 3. No distinct disagreements around coding surfaced during the collegial analytic sessions. Data extraction tables in Excel along with the MAXQDA software were utilized to organize the data. In the next section, we present the dominant PCH narratives and key discursive tensions in this regard, which we identified through the analytic process, along with illustrative examples.

Findings

The Problem of Aging

A dominant discourse surrounding PCHs is that of aging as a social crisis; that is, as an actionable problem requiring an urgent response. Although “aging crisis” discourse is not limited to discussions of PCHs, our analysis leads us to believe that it plays a key role in informing public understandings of the role and function of PCHs as one viable response to this crisis. Indeed, this discourse persists in cultural representations and political rhetoric around aging populations in Western societies more broadly; critical gerontologists have challenged this tendency towards “apocalyptic demography” (Gee, Reference Gee2002; McDaniel, Reference McDaniel1987).

Aging at home versus aging in public

In a publicly available presentation by employees of one regional health authority in Manitoba, “aging in place” is described as “the central principle of Manitoba’s Long Term Care (LTC) strategy”, which seeks to address “placing too many people in personal care homes (prematurely and inappropriately)”(Taylor, Mitchell & Prentice, Reference Taylor, Mitchell and Prenticen.d.). Because there is no official operational definition of the “right” time for someone to move into a PCH, Manitoba’s aging in place strategy seems to inadvertently imply that entering a PCH should be the exception rather than the norm for older people. The assumption that people, in general, would prefer to age in their own homes rather than enter a PCH is echoed by texts that evoke the aging in place strategy. The following are quotes from resources produced by regional health authorities and intended for older people and their families/caregivers.

Many older adults want to remain independent and live in their own communities for as long as possible (Winnipeg Regional Health Authority, n.d.).

Early multi-component, professionally-led interventions for caregivers, including education, training, support and respite, help maintain caregiver mood and morale and reduce strain. It is the only intervention that has been proven to reduce or delay transition from home to a long-term care facility (Manitoba Government, 2014).

These two quotations imply that aging should occur outside of PCHs as much as possible, and specifically that aging is best in the “community” and at “home”. Both quotes appeal to a notion of private responsibility for aging, by naming the primary agents as older adults themselves or their caregivers. The texts we analyzed echo the liminal status of frail older adults: considered collectively, the texts reproduce the idea that there is really no “good” place to care for frail older people in the public sphere, outside of their own private homes. The first quote of the two provided subsequenty, from a union report, might be read to imply that those currently living in PCHs do not belong there, because their medical needs are too great (early discharge here being implicitly characterized as a negative trend, at least from a PCH perspective). And yet, the second quote that follows it, from the Canadian Medical Association president, suggests that “more and more seniors” are inappropriately taking up space in hospitals, as their needs are not acute enough to justify the cost of hospital care.

Long-Term Care facilities are greatly affected by the acuity of their residents. Over the last decade, the acuity level of long term care residents has increased substantially. More and more long-term care facilities are dealing with patients who, in the past, would have been cared for in hospital. Patients are being discharged sooner from hospital procedures and more patients suffering from degenerative illnesses are being cared for and treated in these facilities. (Manitoba Nurses’ Union, 2006, p. 20).

Our hospitals are now filled with more and more seniors not requiring acute care but, because Canada doesn’t have enough long-term care facilities or home-care services for aging baby boomers requiring chronic care, they have nowhere else to go. We’ve come to accept long wait times for surgery, ambulances being turned away and emergency-room patients being treated in hallways. We shouldn’t expect this from our health-care system. Hospitals are not supposed to be in the housing business. Yet 16 per cent of hospital beds—at a cost of more than $800 per day—are tied up with seniors waiting for someplace to go. (C. Forbes, Reference Forbes2016).

This idea that frail older people have needs that exceed what they can access by living at home (an under-resourced and invisible arena to begin with), and whose needs are problematized precisely because they cannot be met at home, underpins calls to increase staffing in PCHs. These calls manifest in union reports as well as in news media stories that contain political comment, advocacy voices, or the voices of family members of PCH residents. One narrative emerging primarily from the news media coverage is that of competition for funding between PCHs and other parts of the health care system. In some instances, there is the notion that public funding is a zero-sum game, where increasing PCH resourcing will detract from funding for the “general public”.

Hospital construction is competing with nursing home needs within the region as well as with provincial funding priorities in other parts of Manitoba, she said in a recent interview. The WRHA’s board of directors approved the region’s new five-year strategic plan earlier this summer. Other capital projects being eyed include the replacement of some aging personal care home spaces and the addition of three new nursing homes (Kusch, Reference Kusch2015).

This is not the dominant narrative, however, as most coverage of the impact of older adults on the health care system actually advocated for increasing funding in order to eliminate “bed blocking” in hospitals and emergency departments. Consider the following statement from the provincial leader of Manitoba’s opposition, Wab Kinew.

“We should be adding personal care homes, we should be adding personal care home beds. We shouldn’t just be freezing things and allow things to get worse,” Kinew said, adding shortages in beds can cause backups in acute care facilities and make wait times longer (Hoye, Reference Hoye2017).

This quote illustrates that even when calls for increasing PCH capacity are not presented as siphoning resources away from the rest of the system, the needs of frail older adults are positioned as a gravitational force that pulls on health care for other citizens. The narrative of older adults taking up spaces unnecessarily in acute care facilities, such as emergency departments and hospitals, echoes the idea underlying the “zero-sum game” calls: that senior care requires precious resources and poses a risk to care access for other members of the public (namely, young and economically productive citizens). At the same time, the alternatives of using paid home care, relying on family caregivers, or moving older adults into a more community-oriented senior housing unit, remain solutions without sufficient attention, resources, or systemic support.

Differences between urban and rural conceptions of “home”

The majority of the texts we examined positioned aging in PCHs as separate from, or even opposite to, “aging in place”, with terms such as “remaining independent” or “in their community” being used as synonymous for remaining in one’s private home. For example, this can be seen in the following quote from the Supporting Healthy Living pamphlet published by the Winnipeg Regional Health Authority (n.d.):

Many older adults want to remain independent and live in their own communities for as long as possible. As needs and abilities change, some people may need extra help to do this. Others may decide to move to a more supportive living environment.

In fact, the phrase “living in the community” was frequently used to imply aging in private, in one’s own private residence with the support of family caregivers. For example, the following quote from a report by Menec et al. (Reference Menec, MacWilliam, Soodeen and Mitchell2002) conflates living in the community with living in a private residence where caregivers are family members: “many dependent seniors are cared for in the community by family members” (p. 47).

This conflation of living in one’s community and living in a private home goes hand in hand with the separation of living in a PCH from living in the community. For example, the following quote from the same report by Menec et al. (Reference Menec, MacWilliam, Soodeen and Mitchell2002) describes the admission process to PCHs, and conceptually separates the PCH from “the community”: “admission to PCHs occurs on the basis of a standardized assessment and can occur from a hospital or the community” (p. 41).

Similarly, calls for increasing support services that delay entrance to PCHs position PCHs as an “institution” in opposition to “community” living options,

This alternative [supportive housing] would allow seniors to live where they prefer - in the community rather than an institution - and at much lower cost to government. (Kusch, Reference Kusch2016).

This pattern of portraying “the community” as synonymous with one’s private home, but not including the PCH, appears to be strictly an urban one. In texts that describe aging in a rural setting, we found that “aging in the community” actually included living in a PCH, provided that the PCH was located in the same community in which the older person normally resided. The term “community” was used to signify not only rural spaces, but also the collective group of people living in such spaces. News media coverage of partnerships between rural towns and the province to build new PCHs described PCHs as a “community need”.

The Pallister government is only focused on the bottom line not the actual needs of communities. Communities were forced to drop important projects for their communities because they could not meet the government’s arbitrary funding target (CBC News, 2017).

In these texts, it appeared that transitioning to a PCH seemed less monumental compared with doing so in an urban setting. If the notion of community is broad enough in the rural context to encompass not only private residences but also local institutions (including PCHs), then perhaps the transition between the two appears less drastic. Indeed, transitioning to a PCH was only portrayed as a drastic change when the PCH was located far from the community where the older person normally resided.

Friesen said families incur a “terrible burden” when a loved one is approved to go into a care home but is told there’s nowhere for them to live near home (Hoye, Reference Hoye2019).

“A number of the couples who had moved into assisted living were finding one spouse had to leave the community because one of them needed long-term care,” said Gordon Daman, who was Mayor of Niverville at the time. “That separation was heartbreaking for them and for their family members” (B. Forbes, Reference Forbes2016).

The emphasis on placing seniors in PCHs located within their geographical, especially rural, community is likely a discursive response to what Grenier and Guberman call “territorial exclusion” (Grenier & Guberman, Reference Grenier and Guberman2009). This type of social exclusion occurs for older adults residing in areas with less access to private and public care options, eroding their participation in society and reflecting a double-pronged experience of social neglect as both rural and older citizens.

An Imperfect Solution to the Problem of Public Aging

PCHs are portrayed as a solution, albeit an imperfect one, to the broader crisis of an aging population, and in particular as a response to meeting the needs of the frailest older adults. However, in this regard, PCHs are themselves portrayed as problematic, because they are places to which “unsuccessful” aging is relegated, in a broader context in which aging itself is a social problem. Understanding how PCHs are perceived in Manitoba requires taking into account narratives of aging as a problem (and public aging as even more so), as clues towards understanding how and why there are competing narratives about what role PCHs ought to play in society.

Increased acuity of older adults

The aging crisis discourse appeared in the texts we examined primarily in relation to the escalating acuity of PCH residents. The language used to describe this trend included adverbs and adjectives such as “longer”, “later”, “more complex”, “older”, and “sicker”, signaling that PCH residents now have greater needs than in the past resulting from a supposed increase in resident frailty (Grenier, Reference Grenier2007). This bolsters the sense of a contemporary aging crisis, while distinguishing current trends as unprecedented and requiring a different and/or more concerted “solution” than what may have worked in the past. This narrative was primarily present in documents published by unions as well as in news media. Consider the following quote from one report.

By living longer and living at home longer, seniors are arriving at care homes at a later stage in their condition with more complex health issues and more physically frail than ever before. The prevalence of chronic conditions and cognitive impairment among residents has increased dramatically over the last decade (Canadian Association for Long-Term Care, 2018).

In this excerpt, the population of PCH residents is also clearly established as being in poor health, and increasingly sick and in need. The phrase “increased dramatically” contributes to a sense of urgency and suggests that the crisis facing PCHs stems directly from changes in the resident population. In a context in which staffing and resident care hours per day have remained stagnant since the 1970s, unions emphasize the increasing acuity of PCH residents in part to highlight the need for increased staffing and resources, as will be addressed further.

Although “aging in place” is promoted as a strategy to address the high demand for, and shortage of bed availability, it is also characterized in other sources as contributing to the high acuity of PCH residents populations and the corresponding sense of crisis (as described).

In Manitoba, this concept of expanded continuum of care is reflected in the “Aging in Place” initiative introduced in 2006. These kinds of initiatives have resulted in increased options for care for aging Canadians, and ideally should result in a more responsive, patient-centered model of care, and are thus a positive step in long-term and advanced care health programs. However, it is important to recognize that a consequence of such programs is that, on average, by the time people do end up in long-term care facilities they are often older and/or have more complex health needs than has historically been the case (Canadian Union of Public Employees Manitoba, 2015, p. 1).

PCHs provide what others cannot

In our analysis, there is also evidence of a narrative that asserts the value and importance of PCHs; this narrative is shaped by texts that highlight how PCHs provide unique services that cannot be accessed through other means. Although this distinguishing aspect of the PCH industry ensures that its contribution to society is valued, the role of PCHs appears to be primarily defined through their capacity to offer what other services do not, or cannot provide. Defining the PCH role in this way leaves ample space for various and potentially conflicting interpretations of what a PCH should do.

For example, the following quote from the Winnipeg Free Press positions public care for the aging population (both PCHs and home care) as necessary because it is for those who “have nowhere else to go”. Although perhaps reinforcing the notion that public services for aging should be a last resort option (discussed in the section entitled “The Option of Last Resort”), this quote also asserts that PCHs and other public supports for aging are unquestionably necessary, because they play a role offered “nowhere else”.

Canada doesn’t have enough LTC facilities or home-care services for aging baby boomers requiring chronic care, they have nowhere else to go (C. Forbes, Reference Forbes2016).

Political and advocacy calls for building more PCHs or “beds”, for example, suggest that, generally, Manitobans value the “basic necessity” that PCH care offers. The following quote from a letter to the editor in the Winnipeg Free Press suggests that there is a collective responsibility for providing PCH placement for older adults, in exchange for their contributions to society. This could also imply that public services for older people compensate for the failures of private resources, and may implicate the failings of family caregivers.

Why is it so hard to provide such a basic human necessity to our elderly citizens who have committed so much to our city over their lifetimes? (Gibbes, Reference Gibbes2018).

In any discussion of this highly emotional topic, it’s wrong to demonize personal-care homes. They provide an important service for Manitobans who need the security offered by around-the-clock staff tending to health needs including medication monitoring, provision of nutritious meals and access to organized activities that allow for much needed companionship (Oswald, Reference Oswald2017).

Interestingly, one exceptional statement from the province’s aging in place strategy frames PCHs as places that offer social companionship, in contrast to the “family home”, which may not always be ideal.

Although the family home may be full of memories, it may also feel very empty, leading to isolation, depression and even malnutrition. (Manitoba Health, Seniors and Active Living, n.d.).

PCHs as Ambiguous Spaces: Home, Healthcare Institution, or Workplace?

A key tension between the narratives we examined is that between notions of PCHs as places that should strive to feel like “home”, and notions of PCHs as places where those who need round-the-clock health care can be accommodated. Based on the data we analyzed, we conclude that social expectations of PCHs overall lie somewhere in between these two narratives, with different sources emphasizing one role more than the other.

Home

PCH mission statements and regional health authority documents, in particular, emphasized that PCHs strive to give residents a sense of “home”. Consider the following quotes.

When we think of places to live, it is important to distinguish between housing and home. While housing meets the human need for shelter, home nurtures growth and spirit. We strive to create an atmosphere that feels like home and are committed to assisting you to feel at home as much as possible (Northern Health Region, 2017, p. 8).

The Home works to meet the physical, social, mental/emotional and spiritual needs of all residents through the combined efforts of a qualified and caring interdisciplinary health care team in accordance with the Manitoba Long Term Care standards. The facility is the resident’s home therefore OSCN PCH provides a safe, home-like environment, respecting the privacy of each resident (Fisher River Cree Nation, 2019).

The second quote exemplifies a discursive pattern seen largely in the PCH mission statements that we examined, whereby the text explicitly lists the multifaceted needs of residents. “Physical” needs are listed first, perhaps as a reflection of the expectation that PCHs are distinguished from other options by the daily physical and medical care provided. The remainder of the needs listed point to the institutional recognition that residents have human needs beyond the physical/medical, and provide a reassuring counterpoint to broader public concerns that PCHs are places where people lose their individual identities through institutionalization. Similarly, the next quote from the Northern Health Region’s Welcome Guide to Long-Term Care describes what might help with “feeling at home” in a PCH. The text connects feeling at home in the PCH institution with personalization, highlighting the idea that the context must respect and acknowledge residents’ individuality in order for it to feel like “home”.

Your comfort is important to feeling at home in your new surroundings. We believe in the benefits of personalizing your room and think your room should be a reflection and extension of you. Personalizing your room with wallpaper and paint is acceptable. It is important to have discussion with the care team prior to beginning the work in your room as you will need to determine how much space you will have for personal furniture items as safety for movement with required equipment needs to be considered (Northern Health Region, 2017, p. 9).

Although the quote begins with the health authority’s position on this matter using “you” to focus on the incoming resident and their individual preferences, it then shifts half-way to emphasize that residents’ personalization choices are bounded and governed by what is considered acceptable by the PCH and the care team. As such, this quote illustrates how attempts to accommodate individual needs and preferences in PCHs are ultimately shaped by institutional structures that constrain a resident’s choices compared with their life outside the PCH. In this respect, we get the sense that although PCHs should strive to feel like home, they may fail to do so.

The idea that PCHs should serve (in a straightforward way) as a residence or housing (as opposed to medical care facilities) is also echoed by union texts that problematize the increasing need for medical care in PCHs.

While long-term care plays a large role in the continuum of care, viewing a long-term care home as a medical facility has been a common misconception. While clinical care is provided, a primary function of a long-term care home is to provide housing for our elderly population. This fact is not well understood and has led to our most vulnerable population not being able to access and benefit from new federal infrastructure investments, including the National Housing Strategy (Canadian Association for Long-term Care, 2018, p. 6).

Whereas personal care homes were traditionally a place where elderly people would go to live with some supervision and basic care, increasingly these facilities are operating as another branch of the acute health care system, providing much of the same types of care provided in hospitals (Manitoba Nurses’ Union, 2006, p. 9).

Many people envision PCHs as supportive places for people to live in their later years. Yet increasingly, these facilities are housing residents who have complex care needs and require a high level of professional care and support. Residents often have multiple medical issues, sometimes psychological challenges, and often dementia, which causes progressive cognitive decline. Indeed, it has been said that PCHs are now providing “acute care for the elderly” (O’Rourke, Reference O’Rourke2012).

The second and third quotes both suggest that PCHs are now functioning outside of the role they perhaps “should” play: for example, as “a place where elderly people would go to live with some supervision and basic care” or “a supportive place for the elderly to live.” Importantly, these descriptions of what PCHs ought to be hinge upon what they used to be, implying that now they fulfill a function beyond their intended role. Specifically, such quotes suggest that the aging crisis has led to an undesirable and unintended change in the function of PCHs, whereby PCHs now must focus more on medical care than they had in the past. The implication here is that PCHs ought to be a place of residence or housing, and that this role is compromised by the increasing medical needs of PCH residents.

Health care institution

In contrast to the preceding narrative, other sources reproduce the view that PCHs are, fundamentally, places where residents can access more medical care than they would in their private homes or in supportive living; therefore, in this respect, they are medical spaces. This narrative manifests in a wide range of types of sources that we examined, including the provincial Personal Care Home Standards Regulation, which falls under The Health Services Insurance Act. The regulation stipulates medical, nursing, and pharmacy services that should be offered in PCHs in great detail (Part 5), whereas recreation and spiritual care programs are briefly included with basic care (dietary services, housekeeping, and laundry) under General Services (Part 6). The relatively greater emphasis (in terms of amount of space and degree of detail) on medical services, in contrast to recreation and spiritual care programs (arguably the psychosocial elements of a home) suggests that the legislation contributes to a view of PCHs as places where medical care is primary and psychosocial services are secondary. Furthermore, the fact that the success of PCHs is measured by the quality of the medical care they offer is echoed in PCH mission statements and regional health authority guides such as the following.

You will not need to leave the facility to get basic medical care such as medication orders, immunizations and basic prescribed treatments. All of the facilities have a specific physician and/or nurse practitioner who regularly visits and will assume responsibility for your medical care. Emergency medical services, after hours and weekends are provided by a physician on-call or at the hospital. If your designate has any medical inquiries, they may arrange to discuss medical treatment plans by contacting the physician’s clinic and making an appointment to see him/her or by meeting with the physician while on rounds at the facility (Northern Health Region, 2017, p. 15).

Workplace

Various narratives fed into the larger discourse that PCHs are part of, and contribute to, a fragile health care system. One of these narratives is that of staffing challenges in PCHs, which is connected to the narrative of a difficult workplace. For example, consider the following quote and its description of a “fragile system”, with the use of the term “fragile” echoing the narrative of PCH residents as highly frail.

Time and again, I have heard from nurses about ongoing challenges in LTC, specifically related to insufficient staffing, increased workloads and the increase of highly acute residents with complex care needs. I applaud the many nurses and members of the public who came forward to share their experiences and provide insight into a fragile system (Manitoba Nurses’ Union, 2018, p. 2).

Although the preceding narratives identify PCHs only as places where people live, they are also places where people work in various capacities, and texts describing care at PCHs (from PCH mission statements, regional health authorities, and union documents) often highlight the impact of residents and workers on each other in these spaces. For example, regional health authority documents and PCH mission statements were most likely to draw positive connections between staff and residents, and in the following quote, this is represented in one regional health authority’s statement that part of the staff’s responsibility is to make the PCH feel like home for residents.

We want our personal care homes to not only “look” like home, but “feel” like home. This affects how we interact with each other, how we do our daily tasks, and how we see our job in general (Southern Health, 2018, p. 3).

Despite this positive portrayal of the relationship between staff and residents (those for whom the PCH is a workplace and those for whom it is a home), it is not the dominant voice that is heard when describing PCHs as workplaces. Instead, descriptions of staffing or the experience of PCHs as workplaces --which originate primarily from union reports as well as from advocacy and political pieces in news media-- are dominated by their characterization as difficult places to work (see also the section entitled “A Dangerous Place”).

Staffing in the evening is one nurse for 40 residents and it takes her the entire shift to complete documentation and meds. If there is a death on the floor, I can imagine it would be chaos because there are a ton of things they have to do (Manitoba Nurses’ Union, 2018, p. 16).

In addition to the high demands of ensuring resident health and safety, these employees are stigmatized as the bottom of the health care ‘hierarchy’: overworked, underpaid, and ignored. (McLean, Reference McLean2013, p. 2)

This narrative is reproduced primarily for advocacy purposes by foregrounding the crisis faced by workers within PCHs, unions, and other voices seeking to lobby for changes to address this problem. Overall however, the characterization of PCHs as undesirable workplaces, alongside and/or intertwined with their characterization as home-like and/or as medical institutions, further contributes to narrative ambiguity and tension that may infuse public perceptions.

The Option of Last Resort

Across the various sources we examined, another dominant narrative portrayed PCHs as a last resort option for older adults. This was echoed by texts that stated, in a matter-of-fact tone, that older adults want to avoid entering PCHs, as well as by political calls for funding and services to help reduce the numbers of people entering PCHs. News media as well as official government documents echoed the sentiment that older people should avail themselves of all possible supports before transferring to a PCH, creating and reinforcing the narrative that PCHs are places that should be avoided. Consider the following quotes from the Winnipeg Free Press.

Let people stay in their home-sweet-homes as long as possible. It’s good for the health of the patients and good for the health of the system (Oswald, Reference Oswald2017).

This alternative (supportive housing) would allow seniors to live where they prefer – in the community rather than an institution – and at much lower cost to government (Kusch, Reference Kusch2016).

A Dangerous Place

Another recurring idea that reinforces the narrative of PCHs as a last resort option is that they are dangerous places. Most commonly represented in news media coverage, this idea is reflected in characterizations of PCHs as places where older adults die from flu outbreaks, faulty fire prevention, understaffing, and abuse/assault. The following quotes are illustrative.

Manitoba’s personal care homes endure “chronic” understaffing that can undermine safe patient care, a new report claims…[the current level “raises the likelihood of several risks, including medication errors and delays, delayed or missed vital sign monitoring and patient falls. There are certainly times where there are shifts when the care is unsafe” Mowat said…the report also links staffing shortages to increased patient agitation, which it says can lead to violence (Pursaga, Reference Pursaga2018).

If “all personal care homes constructed or renovated since 1998 have full sprinkler systems”, and “more than half of the licensed personal care homes in Manitoba do not have full sprinkler systems installed”, there has clearly been very little progress in building assisted-living and nursing homes to accommodate our aging population. Add to this understaffed facilities and overworked home care workers, and it’s no wonder elderly Manitobans are becoming more afraid of getting older than dying (Trethart, Reference Trethart2014).

Indeed, PCHs are portrayed as dangerous places not only for residents, but also for staff (see also notions of a difficult workplace described previously).

“I’ve been bitten, spit at, smacked, punched, choked. It happens on a daily basis”, said one health-care aide who works in a Manitoba nursing home, adding she feared losing her job if she was identified (Nicholson & Kubinec, Reference Nicholson and Kubinec2015).

However, a competing counter-narrative in some sources positioned PCHs as places where residents can in fact be safer than at home. The counter-narrative of PCHs as providing safety that cannot be accessed through other arrangements is evident in various sources, from official documents to popular opinions as reflected in news media coverage. For example, the official provincial definition of PCHs frames them as places where older people can access safety that they cannot access at home.

Personal care services assist Manitobans who can no longer remain safely at home because of a disability or their health care needs (Manitoba Health, Seniors and Active Living, 2019).

Ruth Wyatt, 85, and her husband of 68 years, Claire, recently chose to forego her placement in long term care, even though that would best suit her health needs, in order to stay at home together…[their] daughter is equally concerned for her parents; even though home-care visits four times a day, she knows her mother would be safest in a nursing home (Brohman, Reference Brohman2018).

Opportunities and Promising Narratives

Despite the discursive tensions surrounding PCHs and the accompanying negative undertones in most of the narratives described, there were some instances, particularly in news media, of narratives that had the effect of humanizing PCH residents and, perhaps in turn, softening perceptions of PCHs themselves. These were predominantly human interest stories that countered narratives of PCHs as anonymizing institutions or places where older people lacked quality of life. They ranged from stories of siblings living in the same PCH and sharing important life events, to stories of community members outside the PCH fundraising to provide recreational experiences such as through therapy animals, “robo-pets”, and accessible swings or bicycles.

“It’s fascinating to see their eyes open up, to see how happy they are when they saw this pet,” said Marco Buenafe, a clinical team manager at the Ashern Personal Care Home. “Because most of these residents are like, farmers, they know they like animals … It changes their mood tremendously” (Grabish, Reference Grabish2018).

Recently a woman was swinging [on an accessible swing] with a recreation therapist. The resident recalled a time when she was younger, and fell off a too-high pair of red stiletto shoes. She was just chuckling. And she continued to repeat this story to us throughout the day. And telling us, “Don’t wear red shoes!” It was delightful (Grant, Reference Grant2017).

More than highlighting older residents’ capacity for joy, these stories challenge the narrative that PCHs are consistently difficult places to live. Although it can be argued that the portrayal of joy as a function that is “introduced” through objects of entertainment (e.g., robo-pets or swings) suggests that joy is not inherent to PCH spaces, undoubtedly these human interest stories still offer a portrayal of life at a PCH that complicates the dominant negative representations. In many ways such stories provide a counter-narrative to dominant narratives of PCHs as spaces to be avoided, or spaces where the problem of public aging can be “fixed”. Rather, these stories appear to bridge those living in PCHs with those living in the broader community, as is best seen in stories of intergenerational projects that bring youth and teenagers into PCHs to interact with residents (e.g., Austin, Reference Austin2014).

Discussion

This study joins others (Clark, Reference Clark1993; Gee, Reference Gee2002; McDaniel, Reference McDaniel1987) in documenting a dominant discourse of aging as a social crisis that underpins much of the publicly available material on LTRC that we analyzed. Although some of the material reviewed here represents narratives espoused by key decision makers and PCH actors in Manitoba, such material may nonetheless influence and shape public understandings of the role and function of PCHs, with important implications for the experiences of those who live and work there. Future research can build on our findings to better understand perceptions among the diverse general public, including potential variation by cultural background, and whether and how public perceptions align with the discourses presented in this article.

In Manitoba, as in Canada more broadly, PCHs have been the focus of political and media attention that sparks conversation about the role and quality of services supported by public resources. Much of this discourse depends on an idealized definition of caring, one which we may not even find in the community or home. Nonetheless, this discourse is a powerful driving force for what people expect from PCHs as a public service. Publicly available narratives of the role(s) and purpose(s) of PCHs intersect with societal ideas about necessary public services, and with broader concern about aging as a social crisis: who is supposed to care for the aged, and how? Indeed, the narratives presented, which at first appear to compete with and contradict each other, can be better comprehended when placed within the context of broader discourses about an aging crisis and population aging (Gee, Reference Gee2002; McDaniel, Reference McDaniel1987).

In this article, we use the expression “aging in public” to refer to the experience of aging outside the normative expectations of a neoliberal society, where to age successfully is to age independently and privately, with the unspoken assumption that family will facilitate this process. Aging in public is problematic insofar as individuals, rather than public institutions, are held responsible for the experiences and outcomes of later life. Saunders (Reference Saunders1996) suggests that the narrative of the “aging crisis” can rather be seen as a “crisis of governance,” suggesting that the former problematizes individuals aging in public rather than acknowledging the insufficient public services for the aging population. The concept of aging in public can be used to understand the narrative that PCHs are intended to accommodate a subset of frail older adults who have extraordinary care needs, as reflected by the idea of PCHs as a last resort option in the continuum of care. Recent research highlights a predominant focus on keeping older adults out of LTRC and reducing what are considered to be inappropriate admissions (Jorgensen, Siette, Georgiou, Warland, & Westbrooks, Reference Jorgensen, Siette, Georgiou, Warland and Westbrooks2018; Rahman & Byles, Reference Rahman and Byles2020). Indeed, the texts examined in our study tended to suggest that there is no “good” public place to care for frail older adults, and PCHs were largely characterized as an imperfect or problematic solution to the problem of public aging. This view is echoed in research examining solutions to keeping older adults at home as long as possible (Khadka et al., Reference Khadka, Lang, Ratcliffe, Corlis, Wesselingh and Whitehead2019).

Moreover, although the emphasis on the PCH as a place that should feel like “home” (and which sees home as an idealized setting) reinforces the idea that aging should occur in a home-like environment, it also suggests that one of the roles of PCHs is to compensate for unsuccessful aging by simulating the private sphere. Home is a complex concept and it is important to understand what is meant by creating homelike environments (Board & McCormack, Reference Board and McCormack2018). Our analysis suggests that conceptions of “home” and “community” in textual representations of PCHs varied between urban and rural settings, whereby residing at “home” or “in the community” suggests aging in place in urban-focused texts, but suggests a broader conceptualization in rural-focused texts. In rural contexts, residing in a PCH is not antithetical to being “home” as long as the PCH is located in the same town or municipality where one lived and worked. This provides an opportunity for investigating how transitions to LTRC might be experienced differently by urban and rural residents. It also raises a conceptual question regarding the reach and applicability of “aging in place” discourse between rural and urban locations. Future investigations could help ascertain the relative importance associated with PCHs across geographic areas.

If PCHs are sites of care for those whose needs exceed every other alternative, then the role of LTRC is defined less by what it does and more so by the gaps in the society which it is expected to fill. It is not surprising, then, that one of our main findings is the ambiguity in narratives about the function of PCHs. The tension between narratives that position PCHs in terms of medical care and those that evoke social care (also noted by Armstrong, Reference Armstrong2018) points to a parallel tension in social discourses of aging. Healthy aging entails as little disruption as possible to conventional Western life, reinforcing the dominant discourse of aging in place as successful aging, and leading to the view that PCHs become sites of unsuccessful aging. Further contributing to narrative ambiguity and tension, many texts (e.g., union reports, news media) have characterized PCHs as difficult, even dangerous, places for both living and working, with the latter often evoked for advocacy purposes to lobby for change in the system to protect workers. Public representations of PCHs highlight their role as residence, health care facility, or workplace, but rarely all three simultaneously. The experiences of PCH staff are portrayed through discourses of risk and danger that reinforce narratives of LTRC as undesirable locations for all social actors involved. The problem of public aging then becomes that of a ripple effect emanating from the private failures of individuals, as portrayed by the representations we analyzed.

Overall, we noted considerable confusion about the role and social functions of PCHs in the public narrative. There was broad agreement about the need for PCHs as well as PCHs representing a necessary but imperfect solution to an aging population, which was often framed in terms of a grey tsunami that would engulf the health care system. However, there were diverging narratives as regards the social function and role of PCHs. Notably, there was tension between increasing medical acuity necessitating the need for increasing medical care, and concern about over-medicalization. Likewise, a narrative of making PCHs more like community settings may run up against the need for more medical care (Kane, Reference Kane2015). Second, there were diverging narratives around the role of community versus institutions in care for older adults, with PCHs often viewed as oppositional to communities. However, in rural regions, PCHs were generally viewed as part of the community. Community integration of LTRC, argued to be critical although challenging to achieve, may help reduce the stigmatization of those who live in these care settings (Dupuis, Smale, & Wiersma, Reference Dupuis, Smale and Wiersma2005; Kane & Cutler, Reference Kane and Cutler2015). Third, there were divergent narratives around PCH safety, with these spaces sometimes portrayed as very dangerous, and at other times portrayed as being safer for frail older adults than the community.

There was also some variability around the role of PCHs in relation to the health care system: one expressed role of PCHs is to reduce “bed blocking” and move frail older adults out of the way of those seen as “truly” needing acute hospital care. Although not a new narrative (Hall & Bytheway, Reference Hall and Bytheway1982), it remains a common theme today. PCHs are also seen as necessary institutions for those needing care which cannot be provided in the community. Indeed, PCHs were often defined by what they are not: they are not acute care, they are not community care; they should not look after people who are too well, they should not look after people who are too acutely ill; they are not home-like, but nor are they fully institutional.

PCH narratives, and the findings of this study, have implications for older adults, their families, and staff who work in these settings, as well as for policy makers. It is important for all stakeholders to recognize that the role of PCHs is not clearly portrayed in public discourse, and that public and even official narratives around PCH are quite negative. This in turn may influence public perceptions and increase confusion around the role of PCHs; it may affect the recruitment and retention of staff in these facilities, and exacerbate feelings of guilt, shame, and failure on the part of older adults and their families, when PCH admission is required. These emotions can harm relationships between older adults and family members, and contribute to conflict with LTRC staff. When PCH care is required, open and honest conversations that probe into older adults’ and families’ values, beliefs, and expectations regarding PCH care need to occur. An assessment of discrepant views, stigmatizing beliefs, or concordant perceptions may be helpful in tailoring support to meet the needs of older adults and family caregivers and to facilitate smooth LTRC transitions.

Future research is needed in other regions to investigate the comparability of our findings. Efforts should be made to ascertain perspectives of large culturally and ethnically diverse samples of older adults and their families, caregivers, and community members. Also, perspectives of health care providers and policy makers should also be measured and compared with those of the general population. Finally, further research should consider both more historical and more immediately contemporary time periods. The COVID-19 pandemic that unfolded in Canada and other countries in 2020 has drawn particular attention to these settings, to some extent sharpening the discourse around their role while exacerbating the sense of danger in these spaces both to health care workers and to the broader public. Tracing the evolution of these discourses both during and after the pandemic could be accompanied by assessment of changes in public perceptions of PCHs over time.

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by an internal grant from the University of Manitoba through the University Collaborative Research Program. We thank nursing undergraduate student Megan Bale for her research support.