Introduction

In 2016, more than 400,000 Canadians lived in long-term care or supportive housing (Statistics Canada, 2017a). As our population continues to age, an unprecedented number of individuals will come to live in such congregate arrangements (Statistics Canada, 2017b). Supportive housing is an umbrella term encompassing retirement homes and assisted living (Canadian Centre for Elder Law, 2008). Although some adults 65 years of age or older move to supportive housing from community living, supportive housing remains distinct from long-term care homes (Canadian Centre for Elder Law, 2008; Perks & Haan, Reference Perks and Haan2010). Long-term care homes are provincially regulated institutions that have entry requirements based on care needs, whereas supportive housing provides the option of relocating regardless of need (Howe, Jones, & Tilse, Reference Howe, Jones and Tilse2013).

Within Canadian long-term care homes, person-level data are collected through the mandated use of a standardized instrument (the Resident Assessment Instrument/Minimum Data Set [RAI-MDS] 2.0 or interRAI-Long-Term Care Facilities [LTCF]) across provinces and territories (Hirdes, Mitchell, Maxwell, & White, Reference Hirdes, Mitchell, Maxwell and White2011). These data have played and continue to play a crucial role in shaping long-term care policy in Canada and other countries (Carpenter & Hirdes, Reference Carpenter and Hirdes2013). The lack of a similar data infrastructure in supportive housing impedes evidence-based policy discussions for a sector with fragmented and jurisdiction-specific regulations (Canadian Centre for Elder Law, 2008).

An aging population with increasing care needs places a growing emphasis on supportive housing as an alternative to long-term care (Perks & Haan, Reference Perks and Haan2010) but it is unknown whether these facilities have the capacity to meet residents’ needs (Hirdes et al., Reference Hirdes, Mitchell, Maxwell and White2011). For example, to be licensed in Ontario, a retirement home must offer at least two of the following services: meal provision, bathing assistance, personal hygiene, dressing or ambulation, dementia care, medication administration, incontinence care, or the services of a physician, nurse, or pharmacist (Ontario Retirement Communities Association, 2018). Thus, retirement homes may offer a wide range of heterogeneous services, such as providing meals and medication administration, but whether they can support residents who require additional help with activities of daily living is unclear. Without information on important factors that may be driving residents to relocate to supportive housing, it is difficult to ascertain the level of care needed to best serve this group of older adults.

A recent study from the Hamilton Niagara Haldimand Brant region of Ontario shed some light on the characteristics of retirement home residents by comparing those receiving home care services with home care clients living in the community (Poss et al., Reference Poss, Sinn, Grinchenko, Blums, Peirce and Hirdes2017). Approximately 40 per cent of retirement home residents receive home care services, and they tend to have greater cognitive and physical impairments than their community counterparts (Poss et al., Reference Poss, Sinn, Grinchenko, Blums, Peirce and Hirdes2017). This study also suggests that potential discrepancies exist between the care available in supportive housing and the needs of residents accessing such services. Yet, despite the growing numbers of older adults relocating to supportive housing, their characteristics and needs remain under-studied, hampering any informed assessment of the patchwork of policies implemented across Canada.

An understanding of the existing literature is needed to guide future investigations of prospective supportive housing residents, services, and policies. The push and pull framework, based on Lee’s theory of migration (Lee, Reference Lee1966), is a conceptual guide that is commonly used to examine the factors for relocation. In the context of older adults’ relocation to supportive housing, this framework posits that older adults are influenced by push and pull factors when considering relocation to supportive housing. Pull factors are those that attract older adults to supportive housing, whereas push factors drive them out of their current living situation (Tyvimaa & Kemp, Reference Tyvimaa and Kemp2011). Given the paucity of literature focused on this population, it is unclear how these factors relate to older adults’ health and functioning; hindering the assessment of supportive housing policies’ relative appropriateness.

We therefore conducted a scoping review to describe the nature and content of studies that explore older adults’ reasons for relocating to supportive housing in order to better understand their needs. More specifically, we reviewed studies that examined older adults’ reasons for moving, and their relation to health and function.

Methods

A scoping review is designed to provide an overview of the literature on a topic with an expected paucity of evidence (Armstrong, Hall, Doyle, & Waters, Reference Armstrong, Hall, Doyle and Waters2011). We conducted a scoping review of the supportive housing literature in accordance with Arksey and O’Malley’s (Reference Arksey and O’Malley2005) framework, to achieve our objectives.

Search Strategy

The search strategy was devised to describe the population, the setting, and the outcomes of interest. Because of the heterogeneity of terms used to describe supportive housing, a wide-range of keywords identified in Howe et al.’s (Reference Howe, Jones and Tilse2013) international comparative search of terms was used (Table 1). We searched in PubMed, Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Web of Science, and PsycINFO up to and including August 2018.

Table 1 Search strategy

Article Selection

We included journal articles that focused on individuals who were considering relocating to, or who were are already living in, supportive housing that were published in English between 2000 and August 2018, and for which a full-text version was available. Articles that studied naturally occurring retirement communities — communities of older adults aging in a specific neighbourhood — were excluded because these are distinct from purpose-built supportive housing. Included articles were indexed and duplicates were removed using EndNote X7. Three authors independently screened articles’ titles and abstracts and consulted a senior author to arbitrate screening decisions after full-text review.

Data Charting and Thematic Analysis

Publication characteristics, study characteristics, and participant information were collected and extracted. Publication characteristics included year of publication, journal, country in which the study was conducted, and MEDLINE® indexing status of the journal. Study characteristics included descriptors for supportive housing, study design, and the use of guiding frameworks or models, and participants’ information included age, gender, and measures of health or functioning. MEDLINE indexing status was used as a surrogate for the visibility of the article to health care professionals and policy makers (Matsoukas, Reference Matsoukas2015).

Results were collated by identifying common themes in the literature (Levac, Colquhoun, & O’Brien, Reference Levac, Colquhoun and O’Brien2010). Publication characteristics, general approaches in study designs, and the use of guiding frameworks or models were summarised once charted. Lastly, study participants were described, and measures of health and function were reported.

Results

Search Results

Our database searches returned 15,522 publications, with 13,615 unique citations. A total of 2677 (not counting 128 duplicates) were added after the updated search in August 2018. After screening and full-text review, 34 articles were included (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Overview of Article Selection Process

Summary of Study Characteristics

Table 2 provides an overview of included articles’ study characteristics. Most studies (44%) were conducted it the United States, followed by Australia (21%), Canada (12%), and Europe (12%). Two studies (6%) were conducted each in Israel, China, and Taiwan. More than half of articles (56%) were published between 2007 and 2012, with only 12 per cent having been published before 2006. The majority of studies (65%) were published in journals that were indexed for MEDLINE. Articles were most frequently published in the Journal of Applied Gerontology (15%) and Journal of Housing for the Elderly (12%). The former is indexed for MEDLINE but the latter is not.

Table 2 Study characteristics

Note. ADL = activities of daily living; IADL = instrumental activities of daily living.

The most frequently used descriptor for supportive housing was retirement living, with 44 per cent of studies using “retirement” in their definition of their setting, followed by “assisted living” (21%). Settings that included “retirement” were continuing care retirement communities, retirement villages, and retirement communities. Remaining articles (35%) used a variety of descriptors, such as senior housing/houses (including congregated senior housing and housing for seniors), supportive housing, and government-subsidized senior citizen apartment buildings (Table 2).

The push and pull framework was the most commonly applied framework (27%); half of studies used another conceptual approach, and 24 per cent used none. Almost all 34 articles reported participants’ age and gender, and 65 per cent reported at least one measure of health and/or functioning.

Study Designs

Studies used various designs to explore older adults’ factors for relocating to supportive housing. A qualitative approach was applied in half of the studies, while quantitative approaches were used in 47 per cent (Table 2). Only one study used mixed methods, in which they conducted interviews and applied quantitative instruments (Ewen & Chahal, Reference Ewen and Chahal2013).

Qualitative approaches consisted of interviews with older adults and/or their families who were planning to move to, or already resided in, supportive housing. Most authors analyzed qualitative data using thematic or content analysis (Table 3). A few studies also collected data via participant observation. These studies were guided by a phenomenological approach (Jungers, Reference Jungers2010), a grounded theory approach (Ball, Perkins, Hollingsworth, Whittington, & King, Reference Ball, Perkins, Hollingsworth, Whittington and King2009), and a thematic analysis through micro, meso, and macro lenses (Portacolone & Halpern, Reference Portacolone and Halpern2016).

Table 3 Summary table of reviewed studies

ADL = activities of daily living; IADL = instrumental activities of daily living; SD = standard deviation.

Quantitative approaches largely entailed the use of surveys and questionnaires developed by authors for the purposes of the study (Table 3). The majority of studies used a cross-sectional design to look at relationships between factors surrounding the transition, but a few studies were longitudinal in nature. A pair of studies, for example, administered a survey at two time points, one year apart, to investigate older adults’ relocation outcomes after moving to supportive housing (Smith & Sylvestre, Reference Smith and Sylvestre2008; Sylvestre & Smith, Reference Sylvestre and Smith2009). Two studies used longitudinal data from existing cohorts: the Longitudinal Study on Aging II in the United States (Hong & Chen, Reference Hong and Chen2009) and the ENABLE-AGE Project in Europe (Granbom et al., Reference Granbom, Lofqvist, Horstmann, Haak and Iwarsson2014). Finally, one study used online vignettes to present different scenarios to prospective older adults and their adult children to explore decision-making surrounding relocation (Caro et al., Reference Caro, Yee, Levien, Gottlieb, Winter and McFadden2012).

Guiding Theoretical Frameworks

The majority of studies (77%) used a theoretical framework to guide their inquiry into older adults’ relocation to supportive housing (Table 2). The most frequently used framework was the push and pull framework, which was applied explicitly in 27 per cent of studies, followed by the ecological theory of ageing, which was used in 18 per cent of studies. Different frameworks were used in 32 per cent of articles. The rest of the articles did not report the use of a framework. Table 4 lists these theoretical frameworks.

Table 4 Theoretical frameworks

Most frameworks applied in the studies reviewed were directly related to ageing and relocation: the push and pull framework, the ecological theory of ageing, or frameworks describing different types of movers (e.g. Litwak and Longino Jr’s (Reference Litwak and Longino1987) and Gardner, Browning, and Kendig’s (Reference Gardner, Browning and Kendig2005) models, and concepts designed for examining person–environment interactions (e.g. complementary/congruence model of wellbeing). However, some researchers generalised concepts that are non-specific to older adults or relocation to study this phenomenon, including Rosenbaum’s (Reference Rosenbaum and Rosenbaum1990) theory of learned resourcefulness, grief, ecological system theory (Portacolone & Halpern, Reference Portacolone and Halpern2016), and the theory of planned behaviour (Ajzen, Reference Ajzen, Kuhl and Beckman1985).

Push and Pull Factors Affecting Relocation to Supportive Housing

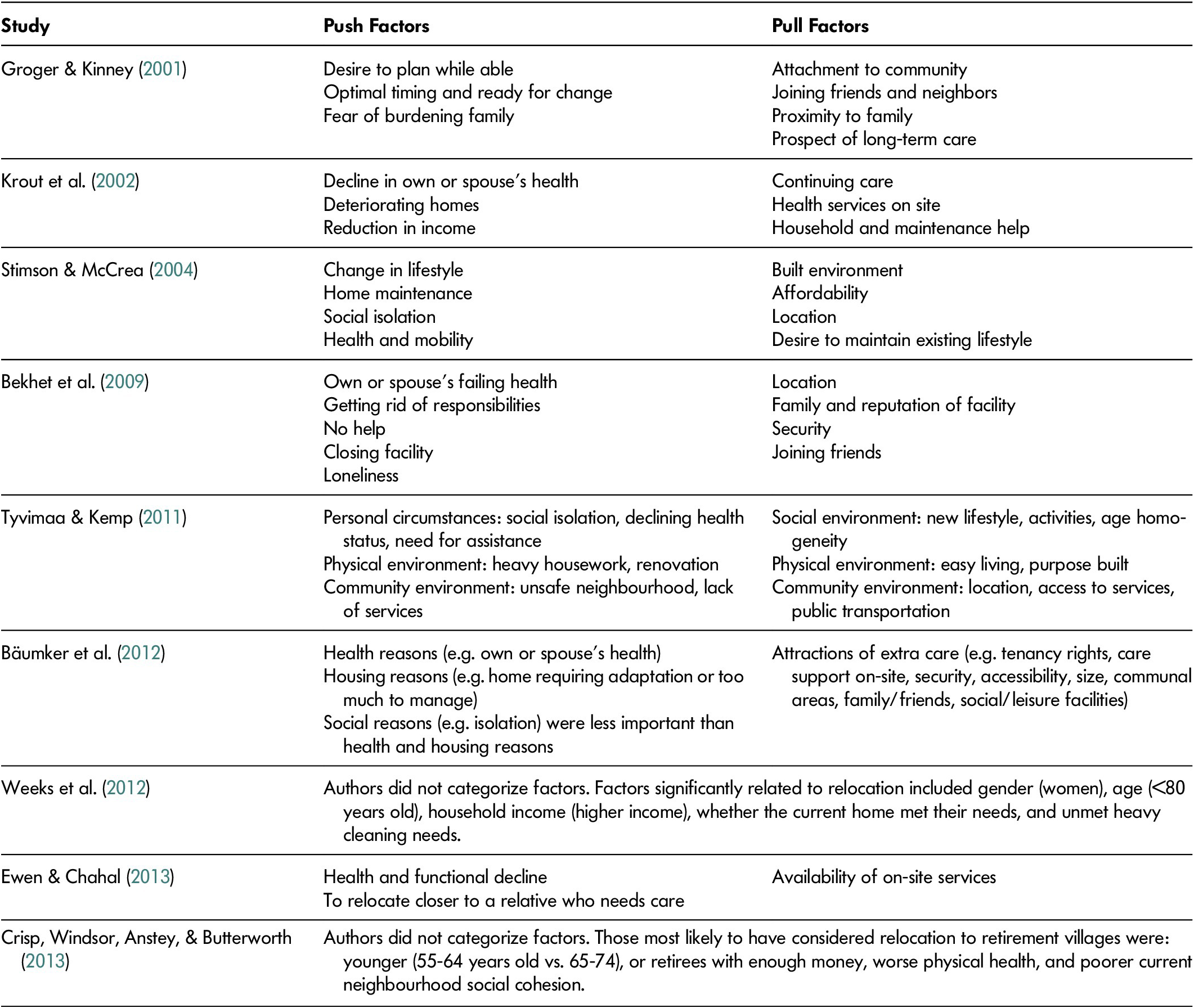

The articles that applied the push and pull framework revealed several factors involved in older adults’ relocation to supportive housing (Table 2). Push factors for relocation included individuals’ or spouses’ health challenges, increasing social isolation, fear of burdening family, inadequate living arrangements, necessary maintenance of property, and aiming to achieve control over one’s future. The most frequently cited push factor in the studies were older adult’s or their spouse’s declining health (Bekhet, Zauszniewski, & Nakhla, Reference Bekhet, Zauszniewski and Nakhla2009; Crisp, Windsor, Anstey, & Butterworth, Reference Crisp, Windsor, Anstey and Butterworth2013; Ewen & Chahal, Reference Ewen and Chahal2013; Groger & Kinney, Reference Groger and Kinney2001; Stimson & McCrea, Reference Stimson and McCrea2004; Tyvimaa & Kemp, Reference Tyvimaa and Kemp2011). Articles that did not explicitly use the push and pull framework also showed that older adults who were relocated experienced increasing physical decline (Svidén, Wikström, & Hjortsjö-Norberg, Reference Svidén, Wikström and Hjortsjö-Norberg2002), falls (Castle & Sonon, Reference Castle and Sonon2007; Saunders & Heliker, Reference Saunders and Heliker2008), cognitive impairment (Rockwood et al., Reference Rockwood, Richard, Garden, Hominick, Mitnitski and Rockwood2014), and/or functional deficits (Ewen & Chahal, Reference Ewen and Chahal2013; Granbom, Lofqvist, Horstmann, Haak, & Iwarsson, Reference Granbom, Lofqvist, Horstmann, Haak and Iwarsson2014).

Pull factors for relocation were related to one’s lifestyle, community and social amenities, the prospect of receiving care, and affordability (Table 5). Pull factors generally involved the availability of amenities and care that enabled older adults to maintain an existing lifestyle (Stimson & McCrea, Reference Stimson and McCrea2004). Articles that did not apply the push and pull framework also suggested that reasons for relocation related to the maintenance of older adults’ current lifestyle. For example, Kemp (Reference Kemp2008) found that couples who moved to assisted living homes did so because of their desire to continue living together after a spouse’s major health transition. The push and pull factors are described in Table 5.

Table 5 Push and pull factors affecting relocation

Other Factors Influencing Relocation

Articles that used other models or no explicit guiding conceptual framework described additional factors, which may or may not be related to push and pull factors, influencing older adults’ relocation to supportive housing. An article that used the ecological theory of ageing examined how different dimensions affected relocation: functional status, features of current housing, social networks, features of retirement communities, and finances (Caro et al., Reference Caro, Yee, Levien, Gottlieb, Winter and McFadden2012; Sergeant & Ekerdt, Reference Sergeant and Ekerdt2008). Another article described how increasing dependence results in changes in the person–environment fit, which may precipitate the move (Granbom et al., Reference Granbom, Lofqvist, Horstmann, Haak and Iwarsson2014). Using the ecological theory of ageing, Koss and Ekerdt (Reference Koss and Ekerdt2016) categorised older adults’ reasoning for relocation as pre-emptive, where participants believed that their current homes would be suitable in the future, or contingent, where they have anticipated having the need to relocate.

Reviewed articles also explored the impact of adult children (Castle & Sonon, Reference Castle and Sonon2007; Sylvestre & Smith, Reference Sylvestre and Smith2009), older adults’ subjective interpretations of the new residential setting (Smith & Sylvestre, Reference Smith and Sylvestre2008), socio-economic status and race (Ball et al., Reference Ball, Perkins, Hollingsworth, Whittington and King2009), learned resourcefulness (Bekhet, Zauszniewski, & Wykle, Reference Bekhet, Zauszniewski and Wykle2008), grief (Ayalon & Green, Reference Ayalon and Green2012), and the larger cultural and political context (Portacolone & Halpern, Reference Portacolone and Halpern2016; Sergeant & Ekerdt, Reference Sergeant and Ekerdt2008) as factors for relocation.

Study Participants

All articles reported participants’ gender, and all but one (97%) reported participants’ age (Table 2). With the exception of one study that included only women (Saunders & Heliker, Reference Saunders and Heliker2008), 60–70 per cent of participants were women (Table 3). All mean and median ages were greater than 60 years (Table 3). Younger participants (with a mean age of 65 years old) tended to be community-dwelling residents who may have been relocating to supportive housing (Crisp, Windsor, Anstey, & Butterworth,, Reference Crisp, Windsor, Anstey and Butterworth2013; Weeks, Keefe, & Macdonald, Reference Weeks, Keefe and Macdonald2012). In contrast, in articles with participants who were already living in supportive housing, the participants were 70–80 years old (Bäumker et al., Reference Bäumker, Callaghan, Darton, Holder, Netten and Towers2012).

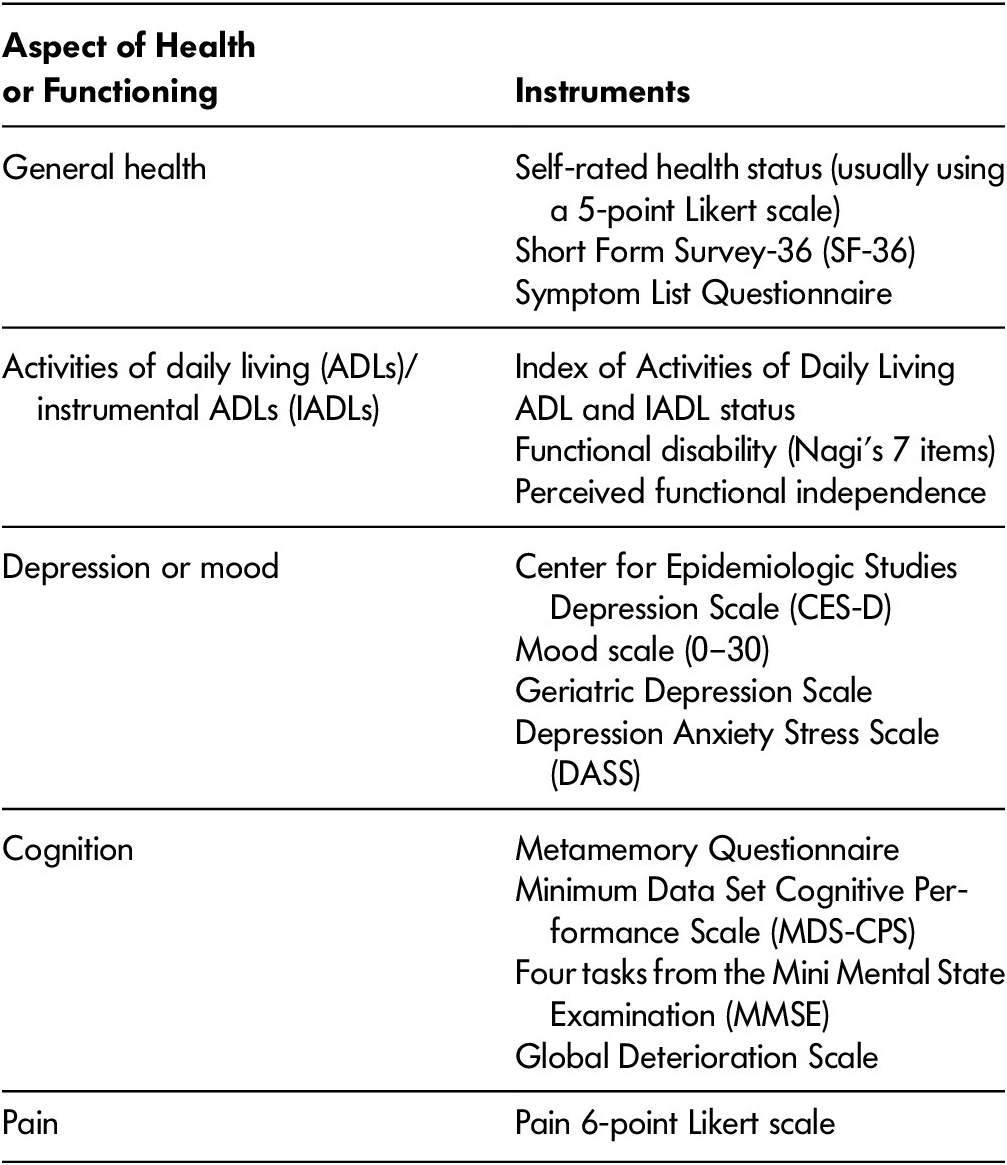

Participants were often described as healthy (Walker & McNamara, Reference Walker and McNamara2013) and/or cognitively unimpaired (Bekhet et al., Reference Bekhet, Zauszniewski and Wykle2008); no studies focused on older adults with significant physical and/or cognitive impairments. Approximately two thirds of studies used at least one measure of health or functioning (Table 6). Up to 62 per cent assessed general health, with self-rated health being the most frequently used instrument. Activities of daily living (ADLs) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) were the second most frequently assessed aspect of health and functioning, with 32 per cent of studies applying an instrument to measure them. Other standardized instruments, such as the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) and the Minimum Data Set Cognitive Performance Scale (MDS-CPS), were used to measure depression/mood and cognition, respectively (Table 6). A total of 12 per cent of studies collected information related to specific health conditions from patients and/or their medical records (Ball et al., Reference Ball, Perkins, Hollingsworth, Whittington and King2009; Ewen & Chahal, Reference Ewen and Chahal2013; Hong & Chen, Reference Hong and Chen2009; Sergeant & Ekerdt, Reference Sergeant and Ekerdt2008). Cardiovascular disease and hypertension were the most commonly reported health conditions (Ball et al., Reference Ball, Perkins, Hollingsworth, Whittington and King2009; Ewen & Chahal, Reference Ewen and Chahal2013; Sergeant & Ekerdt, Reference Sergeant and Ekerdt2008).

Table 6 Instruments to assess health and/or function

Articles that commented on participants’ health or functioning generally stated that participants were in good physical health with only minor problems. For example, Groger and Kinney (Reference Groger and Kinney2001) reported that participants had high levels of well-being, with the exception of a few reporting minor “forgetfulness” problems. Studies that used self-rated health as a measure of general health commonly reported that participants were in “fair” or “excellent” health (Bekhet et al., Reference Bekhet, Zauszniewski and Nakhla2009; Huang, Reference Huang2012; Weeks et al., Reference Weeks, Keefe and Macdonald2012). Some of the articles suggest some deficits in ADLs/IADLs among study participants. One study reported average scores of 7.2/10 and 5.5/10 on the Older Americans Resources and Services ADL and IADL Scales (Castle & Sonon, Reference Castle and Sonon2007), whereas another found that only 31 per cent of 215 retirement home residents were independent with two or more IADLs (Caro et al., Reference Caro, Yee, Levien, Gottlieb, Winter and McFadden2012). The three articles that examined how health and functioning impacted relocation found that worse health, dependence with IADLs, cognitive deficits, and accessibility problems were associated with moving to supportive housing (Granbom et al., Reference Granbom, Lofqvist, Horstmann, Haak and Iwarsson2014; Hong & Chen, Reference Hong and Chen2009; Rockwood et al., Reference Rockwood, Richard, Garden, Hominick, Mitnitski and Rockwood2014).

Discussion

We conducted a scoping review to identify and describe manuscripts reporting on older adults’ reasons for relocation to supportive housing. Of the 34 articles that met eligibility criteria, 12 per cent described studies that were conducted in Canada; the majority were published after 2007. Thirty-five percent of articles were published in a journal not indexed for MEDLINE, which may hinder their visibility to health services researchers. As a result, literature regarding older adults’ reasons for relocating to supportive housing may be under-utilised to inform the planning and delivery of care, and refinement of supportive policy. This may also explain why the literature may focus on the geographical and planning aspects of older adults’ relocation rather than health-related factors.

Articles reviewed were heterogeneous. First, numerous descriptors were used to designate purpose-built housing that provides services for older adults, ranging from “senior housing” to “retirement homes”. This is consistent with previous reviews of supportive housing nomenclature, suggesting that commonalities exist among settings despite the diversity in descriptors used (Howe et al., Reference Howe, Jones and Tilse2013). Second, studies employed a variety of qualitative and quantitative designs. Despite differing approaches, both qualitative and quantitative studies had a shared purpose: to understand the factors driving older adults’ relocation to supportive housing. Notably, some articles reported using similar frameworks despite using different study designs. For example, Groger and Kinney (Reference Groger and Kinney2001) used the push and pull framework to analyze interview data, whereas Stimson and McCrea (Reference Stimson and McCrea2004) used the framework to guide the development of a model from survey data.

The use of a guiding framework or model was reported in 76 per cent of manuscripts. One third of articles that used a guiding model explicitly applied the push and pull framework, making it the most frequently used conceptual framework. Another commonly used conceptual framework was the ecological theory of ageing, which revolves around the person–environmental fit (Granbom et al., Reference Granbom, Lofqvist, Horstmann, Haak and Iwarsson2014). Despite the use of different guiding frameworks and models, there appears to be a common theme among the reviewed articles: a combination of push and pull factors influences older adults’ relocation to supportive housing. For example, “environmental press”, as described in the ecological theory of ageing, is analogous to push factors. Another example includes the Gardner’s model of two types of movers that categorises older adults into planners and reactors (Crisp, Windsor, Butterworth, & Anstey, Reference Crisp, Windsor, Butterworth and Anstey2013), echoing that some are pushed into relocating to supportive housing and must move reactively, whereas others may be pulled into relocating by planning around their anticipated future needs.

Generally, the reviewed studies, specifically those using qualitative approaches, provide valuable insight into the influence of older adults’ lived experiences, albeit framed a priori using guiding models, on their relocation to supportive housing. Perceived and actual decline in health or health of a spouse were the most commonly cited push factors. Pull factors generally revolved around the availability of amenities and support that participants anticipated that they would need in the future. Importantly, these factors are also consistent with the results of articles which did not explicitly utilise the push and pull framework, suggesting that these findings are not just artifacts resulting from the use of this guiding model. Articles also explored potentially influential variables, such as the role of adult children and grief, which modify older adults’ experiences with relocation but do not necessarily push or pull them towards supportive housing.

Overall, studies that included both community-dwelling and supportive housing residents showed that those residing in supportive housing tended to be older and were mostly women (Crisp, Windsor, Anstey, & Butterworh, Reference Crisp, Windsor, Butterworth and Anstey2013; Weeks et al., Reference Weeks, Keefe and Macdonald2012). This may be because women have a longer life expectancy than men, and because of the association between increasing age and health and functional deficits. The likelihood that women are the surviving partner in their relationship may contribute to their relative overrepresentation in supportive housing. Many men with similar health and functional challenges may have partners to help them avoid moving to supportive housing (Rockwood, Song, & Mitnitski, Reference Rockwood, Song and Mitnitski2011). Approximately two thirds of articles used at least one measure of health or function, and most participants were described as healthy, with a few being described as having minor deficits in functioning. However, three articles examined the impact of health and functioning on relocation to supportive housing (Granbom et al., Reference Granbom, Lofqvist, Horstmann, Haak and Iwarsson2014; Hong & Chen, Reference Hong and Chen2009; Rockwood et al., Reference Rockwood, Richard, Garden, Hominick, Mitnitski and Rockwood2014). These manuscripts reported that physical impairments and functional impairments were associated with moving to supportive housing. The instruments used to assess health and function varied and often relied on self-report. The limited and largely subjective data on participants’ health and functioning hinder the extrapolation of whether needs are met in supportive housing.

This review of 34 articles reporting on factors surrounding older adults’ relocation to supportive housing revealed several gaps in the literature. First, the results of reviewed articles suggest that older adults are pushed into supportive housing by declining physical health and functioning. However, details about this decline, such as diagnoses and comorbidities, are limited by the variable use of instruments and reliance on self-report. Second, there is a collage of different terms used to describe supportive housing, which hinders comparisons and policy discussions with regard to this setting (Howe et al., Reference Howe, Jones and Tilse2013). Third, financial considerations were identified in a small number of studies, which is surprising given the costs often associated with supportive housing options (Federal/Provincial/Territorial Ministers Responsible for Seniors, 2019). Moreover, considerations related to gender identity, culture, and religion appear to be virtually absent from the literature. Lastly, evidence regarding supportive housing consists of both health-related and non-health-related literature. Although this body of evidence facilitates a multidimensional understanding of older adults’ relocation to supportive housing, active efforts may be required to bridge silos between disciplines.

Gaps identified in this review make it difficult to ascertain the appropriateness of current policies. Although evidence suggests that older adults relocate to supportive housing in part because of health and functional impairments, there appears to be a paucity of comprehensive and observational literature to support this. In Canada, the Federal/Provincial/Territorial Ministers Responsible for Seniors (2019) recently called for more evidence that considers the many factors at play, including socio-economic and cultural ones, to guide policies for older adults’ housing. Future research should focus on collecting and summarising objective information about the health and functioning of older adults relocating to supportive housing. Longitudinal observational study designs may be particularly useful because the current literature suggests that changes in older adults’ health and functioning often prompt relocation. This study design can facilitate a detailed understanding of older adults’ needs, and consequently, inform policies relevant for both older adults contemplating moving to and those already residing in supportive housing. The application of guiding frameworks and models appears to be useful in exploring health-related and non-health-related factors that influence the transition to supportive housing. However, the use of a framework such as Andersen’s behavioral model of health services use (Babitsch, Gohl, & von Lengerke, Reference Babitsch, Gohl and von Lengerke2012) may be more comprehensive in capturing predisposing, enabling, and need factors associated with relocation.

Finally, standardized nomenclature for supportive housing needs to be established to facilitate the synthesis of this evidence, and national and international comparisons of related policies. The mandatory use of interRAI standardized assessments systems in the long-term care and home care sectors across Canada provides a rich resource with which to better understand the clients served in these sectors and guide policy (Heckman, Gray, & Hirdes, Reference Heckman, Gray and Hirdes2013). It is time for a similar approach to be implemented in the supportive housing sector.

Strengths and Limitations

Our scoping review should be interpreted in light of its strengths and limitations. The strengths of this review are the non-restrictive inclusion criteria that encompassed all study types, the use of multiple databases spanning multiple disciplines, and the use of a systematic process documented using reference management software. This review is limited by the exclusion of non-English articles. Finally, our focus was on the identification of factors related to relocation decisions. A number of articles identified also addressed lived experience of the actual relocation and of its aftermath on quality of life in a supportive care setting, which, as important topics, would require specific reviews and further research.

Conclusion

This scoping review describes the nature and content of 34 articles focusing on older adults’ reasons for relocating to supportive housing. Approximately one third of included articles were published in journals not indexed for MEDLINE, which suggests that a portion of literature focuses on non-health-related aspects of supportive housing, such as geography and planning. This is also reflected in the heterogeneous study characteristics that included various qualitative and quantitative designs and different guiding conceptual theories. Ideas explicitly or implicitly related to the push and pull framework were common in the articles. It was frequently reported that declining health and functioning was a commonly cited push factor towards relocation to supportive housing. However, although two thirds of the articles utilised a measure of health or functioning, most relied on subjective and self-reported measures. Future research is needed to produce data regarding the health and functioning of older adults moving to supportive housing to better inform policies for this growing population.