Since Xi Jinping 习近平 assumed power in 2012, China appears to be taking a fresh approach to managing its state-owned enterprises (SOEs). The Economist has dubbed this the era of “Xinomics,” characterized by a “new economic agenda” aiming to “make markets and innovation work better within tightly defined boundaries and subject to all-seeing Communist Party surveillance.”Footnote 1 In this view, China's current leadership has swerved off the path of gradual marketization, once defined by deepening support for a semi-autonomous private sector and embrace of “government-enterprise separation” (zhengqi fenkai 政企分开) in SOE management. A profound shift now appears underway, towards a system in which the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) intervenes more directly and forcefully in corporate decision making.

We analyse this departure narrative as it applies to the party-state's management of SOEs. How has governance of the state-owned economy changed under Xi Jinping? We compare the Xi administration (2012–present) to that of his immediate predecessor Hu Jintao 胡锦涛 (2003–2012). In contrast to accounts of a radically different “Xi era,” we find that the core visions of Xi and Hu for SOEs have been surprisingly consistent: achieving state control and market competitiveness on a global scale via concentrated state ownership and overseas expansion. Similarly, our analysis of the governance mechanisms employed by the Xi administration suggests a deepening of pre-existing trends, which we define as the elevation and formalization of extant practices, rather than wholesale departure.

This article proceeds as follows. The following section reviews perspectives about a putative “Xi era” in SOE governance. Next, we analyse how Chinese leaders’ vision for SOEs formed during the 1990s as well as the Hu and Xi administrations’ respective approaches to implementation. We identify incremental deepening of Party influence under Xi and discuss its domestic, international and corporate consequences. Finally, the paper concludes by identifying questions for future research as the Xi administration continues.

A “Xi Era” in SOE Governance?

As Xi Jinping nears the end of his second five-year term in 2022, scholarly and analyst perspectives on his administration are solidifying. For numerous observers, a distinctive “Xi era” in SOE governance is apparent, characterized by departure from the gradual marketization of the past in favour of centralized CCP control. In this view, China under Xi has entered a “counter-reform era,” marked by the closer integration of state and Party bodies as well as declining political will to impel SOEs to adapt to market forces as autonomous firms.Footnote 2

Some who posit an emergent “Xi era” in SOE governance perceive stagnation and even abandonment of earlier reform efforts. In such accounts, the bold market-oriented reforms of the 1980s and 1990s have faltered, largely owing to growing barriers within the state.Footnote 3 As Elizabeth Economy writes of China under Xi: “Nowhere is stasis more evident than in efforts to reform the system of SOEs. Not only has there not been progress … but in a number of respects it is moving backwards.”Footnote 4 The state now appears to be “striking back,” reversing earlier reformist gains through increasing use of industrial policies and subsidies to support SOE business in domestic and international markets.Footnote 5 Although Xi is the protagonist in such accounts, some also interpret this break from the past as a hardening “partial reform equilibrium.”Footnote 6 Reports of systemic “collusion” between officials and state firm managers, for example, imply that interest groups embedded in the state have successfully stymied marketizing SOE reforms.Footnote 7

To most, however, the defining feature of a new Xi era is embrace of centralized CCP control. According to such analysis, the magnitude of Xi's efforts to ramp up Party influence over both state and non-state firms at home and abroad has transformed “China Inc.” into “CCP Inc.,” signalling a “new paradigm” in the country's development trajectory.Footnote 8 Under Xi, China has shifted from state capitalism to “party-state capitalism”: the Party's economic activities now “place politics in command with state capitalism more directly in the service of the party's political survival.”Footnote 9

Others contend that changes to SOE organization, too, distinguish the new Xi era from the past. In addition to greater blurring of public–private boundaries, these observers cite the Xi administration's directive that SOEs revise their articles of association to formalize the CCP's leadership role.Footnote 10 In this way, the corporatization of state firms that was earlier interpreted as a key step in market reform has, paradoxically, provided the basis for deeper integration of the political and commercial under Xi's rule. As Tamar Groswald Ozery observes: “Especially since Xi Jinping rose to power, political involvement in corporate governance has been extended far beyond what had existed earlier since China's economic reforms began.”Footnote 11

The emerging consensus in recent writing about Xi's economic governance is that “Xinomics” marks a decisive break with the past. We query this departure narrative through a two-step comparative analysis of Xi's and Hu's management of SOEs. First, we examine their vision of post-retrenchment governance of the state-owned economy. Second, we analyse how they implemented this vision and its consequences.

Envisioning State Ownership 2.0: “Grasping the Large” and “Going Out”

Deep crisis in the state-owned economy during the late 1990s prompted China's leaders to formulate a new vision of state ownership. For the first two decades of reform, China's leaders had approached this issue cautiously because SOEs formed the basis of the state's social contract with citizens and provided political stability. Faced with worsening financial crisis, the Jiang Zemin 江泽民 administration initiated the era of “reform with losers” through radical retrenchment of the state sector.Footnote 12 It gave large SOEs a new mandate: instead of providing an “iron rice bowl” (tie fanwan 铁饭碗) for China's urban population, they were to anchor state control in key sectors and also lead Chinese firms’ advance into global markets. This vision of state ownership 2.0 has informed SOE policymaking since the late Jiang period.

During the 1990s, political commitment to the state-owned economy rose even as its economic performance declined. By the end of the decade, many SOEs were deeply in debt, and state firms accounted for virtually all of state-owned banks’ non-performing loans.Footnote 13 As economic stagnation worsened, Chinese policymakers did not eliminate state ownership; instead, they chose to “grasp the large” and “let go of the small” (zhua da fang xiao 抓大放小). Thousands of small and medium-sized SOEs were sold off or allowed to go bankrupt, while other SOEs were corporatized by introducing corporate governance institutions without privatization.Footnote 14 Simultaneously, the state “grasped” large SOEs in industries with high strategic value, such as defence and telecommunications, while reducing state ownership overall.Footnote 15 Within designated industries, the strategy further concentrated state ownership in a small group of “national champions”: large, centrally controlled SOEs.Footnote 16

An enduring legacy of the leadership's policy choices in the late 1990s was crystallization of a “market vision” for the state-owned economy.Footnote 17 Leaders envisioned post-retrenchment SOEs that would be internationally competitive and market-conforming while simultaneously tethered closely to the party-state.Footnote 18 Having lanced the boil of a state sector that did not adapt to marketization – with accordingly painful results for the legions of “let go” SOE workers with a scant safety net to catch them – the leadership aspired to create next-generation SOEs with the market share, technology and capital to go head-to-head with foreign multinationals at home and abroad.Footnote 19

In parallel to retrenchment of state ownership, China's leaders began urging national team SOEs to “go out” (zou chu qu 走出去). Jiang Zemin encouraged high-performing Chinese firms to do business abroad and establish production facilities in Africa, Central Asia, the Middle East, Eastern Europe and Latin America.Footnote 20 Hu Jintao's administration later strengthened this commitment. The 16th Party Congress (2002) report formally adopted “going out” as a “major measure taken in a new stage of China's reform and opening movement.”Footnote 21 The state spurred SOEs to pursue international investments, conduct cross-border mergers and acquisitions, form joint ventures overseas and establish overseas-registered subsidiaries.

Mechanisms of Governing the State-owned Economy

During the reform era, China's leaders have employed multiple means of governing the state-owned economy: bureaucratic design, the cadre management system, Party organizations and campaigns. Bureaucratic design involves each administration's choices about the organization and supervisory authority invested in state bodies for policymaking, oversight and performance assessment. While the state's role as owner is fixed, the way in which it designs and deploys the bureaucracy to govern the state-owned economy is not. There is no one-size-fits-all approach to bureaucratic design and it has varied significantly in China over time.

The cadre management system is a key means of governing the state-owned economy because Chinese SOE leaders are both executives and state officials.Footnote 22 Leadership rotation and joint appointments are powerful tools for the centre to shake up existing leadership teams and limit potential “departmentalism” (benweizhuyi 本位主义).Footnote 23 They also function to limit executives’ ability to develop strong personal networks and autonomous bases of influence in their enterprises.Footnote 24 Joint appointments, in which a single individual serves simultaneously in two or more of the top executive and Party leadership roles (Party secretary, general manager, and/or board chairman, if a board exists), also act as a tool of control by embedding SOEs in the party-state bureaucracy. Joint appointments have been a long-standing practice in China under the principle of “two-way entry, overlapping position holding” (shuangxiang jinru, jiaocha renzhi 双向进入,交叉任职).Footnote 25

Chinese leaders also leverage Party organizations, in particular SOE Party committees, to govern the state-owned economy. SOE Party committees exist at the group company level and also within subsidiaries. The Party Constitution directs them to provide “guidance,” “oversight” and to “stimulate the healthy development of the enterprise.”Footnote 26 In practice, Party committees primarily serve personnel and political functions: selecting and evaluating senior personnel, recruiting Party members, circulating political propaganda and organizing study sessions.Footnote 27 SOE Party committees at the group company level also have agenda-setting power via their authority to discuss “major decisions” before they go to the board of directors for final determination.Footnote 28 While no official central guidance exists concerning what specifically constitutes “major decisions,” Party documents list examples, including decision making about corporate strategy, budgets, senior personnel affairs and capital management.Footnote 29 SOE Party committees also coordinate with higher-level Party authorities, for example in the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC) and the State Council, to implement central-level policies and campaigns.

Campaigns are a final means by which the party-state governs the state-owned economy. Campaigns leverage high levels of bureaucratic and citizen mobilization to remake existing organizations and/or practices in a particular policy area.Footnote 30 Chinese leaders use campaigns to govern in several ways. First, campaigns shake up the status quo in SOEs and direct mass participation and resources towards centrally determined goals. Campaigns also target and remove individuals who oppose central policies or engage in illicit behaviour. They can further strengthen the party-state's long-term ability to govern SOEs by demanding individual loyalty and increasing pressure for ideological conformity. The following section investigates how the Hu administration employed these governance mechanisms and their results.

The Challenges of Coaching the National Team: The State Sector under Hu

The Hu administration (2002–2012) implemented the post-retrenchment market vision for SOEs first and foremost through bureaucratic design. It made a new bureaucracy, SASAC, the centre of gravity in SOE governance, with the cadre management system, Party organizations and campaigns playing a supporting role.

Bureaucratic design

The Hu administration's first challenge was to design a bureaucracy to manage state-owned assets. The 1993 Company Law legally incorporated SOEs, but no ownership agency existed to govern them on the state's behalf. As a former official explained the dilemma: “The Company Law was intended to solve the ownership issue at the company level, but it did not create an institutional framework at the national level for the management of SOEs.”Footnote 31 In 1998, the Jiang administration dissolved the State Assets Administration Bureau, the central-level government agency previously solely responsible for state-owned asset management, but it did not create a replacement. The Hu administration therefore inherited a situation of “five dragons ruling the waters” (wu long zhi shui 五龙治水) in which authority for SOE administration was fragmented among multiple central-level agencies.

The Hu administration created SASAC under State Council authority in 2003. At its inception, SASAC administered a portfolio of 189 central SOEs, divided into core and non-core firms, all in non-financial sectors.Footnote 32 It enjoyed full ministerial rank and a relatively large personnel allocation of 555 staff.Footnote 33 While SASAC was to stay out of enterprises’ daily decision making, it had a broad operational mandate to “manage assets, people and affairs” (guan zichan, guan ren, guan shi 管资产,管人,管事). With regard to personnel management, SASAC was authorized to appoint the leaders of non-core SOEs. It also used administrative directives, information reporting and periodic on-site inspections by its supervisory board members to monitor central SOEs.

The Hu administration tasked SASAC with remaking the state-owned economy in accordance with the post-retrenchment market vision. SASAC continued and intensified efforts to consolidate state ownership in a smaller number of large state-owned firms in strategically important sectors. Founding SASAC director Li Rongrong 李荣融 (2003–2010) stressed the importance of making SOEs big and strong (zuo da zuo qiang 做大做强) to compete with multinational corporations at home and abroad, and he pledged that any central SOE that failed to rank in the top three in its industry would be eliminated. Under SASAC's direction, more than 70 central SOEs were either merged into existing firms or combined to create new national champions between 2003 and 2010.Footnote 34 SASAC also facilitated the public listing of SOE assets on domestic and international equity markets and recentralized operational control over budgeting and profit remission.Footnote 35

But as the 2000s continued, deficiencies in the Hu administration's SASAC-reliant approach to SOE governance became increasingly apparent. State firms’ assets, organizational complexity and international operations all expanded rapidly, curtailing SASAC's ability to monitor them effectively.Footnote 36 Furthermore, SASAC had few sticks with which to discipline firms that did not fully comply with information-reporting requirements, especially core central SOEs for which it was not authorized to appoint, transfer or remove leaders. Wang Junhao, Xiao Zhijing and Tang Yaojia sum up the difficulty of regulating increasingly large and politically powerful SOEs as “the cat wants to catch the mouse, but the mouse is bigger than the cat.”Footnote 37

Cadre management system

Having placed its bets largely on the SASAC system, the Hu administration did not leverage the cadre management system as strongly. During the decade-long Hu administration, 14 top executives were transferred from one core central SOE to another, with leadership rotation occurring at an average rate of 1.4 transfers per year.Footnote 38 Only one bilateral swap of top leaders within a single industry occurred, in the electricity sector in 2008. Limited shuffling involving broader segments of company leadership also took place, such as in the airline sector in the same year, but this was infrequent.

Nor does it appear that the Hu administration dangled the carrot of political advancement to incentivize compliance with SASAC directives. Among core central SOEs, for example, 55 per cent of top leaders who moved on between 2003 and 2012 went straight into retirement.Footnote 39 Those who advanced politically followed one of three routes, with little overlap: to other core central SOEs; provinces or municipalities; or the centre. More than 90 per cent of these appointments were lateral transfers to positions of equivalent administrative rank rather than promotions.Footnote 40 With retirement for the majority and lateral transfers the norm for the rest, positive political inducements for SOE leaders were limited.

Joint appointments for SOE leaders were routine throughout the Hu administration. Among core central SOE leaders, for example, the average incidence of any combination of multiple Party and managerial roles was 76 per cent.Footnote 41 The overall frequency of joint appointments was steady across the decade-long Hu administration, with the general manager/Party secretary combination the most common pairing of leadership roles. As the challenges of governing the state-owned economy grew throughout the 2000s, the Hu administration did not increase joint appointments of Party and managerial leadership roles to bring SOE executives more firmly under political control.

Party organizations

Under Hu, Party organizations played an important formal and informal role in SOE decision making. The development of corporate governance institutions during the 2000s affirmed an implicit division of labour in which SOE Party committees focused mainly on political and personnel matters, while the board of directors handled commercial decision making with limited shareholder input and nominal supervisory board oversight. Internal documents described the purpose of SOE Party committees using the term “political core function” (zhengzhi hexin zuoyong 政治核心作用); the terminology of “leadership function” (lingdao zuoyong 领导作用) was less common than it would become under Xi.Footnote 42 The principle of the Party committee having decisive input on issues involving the “three majors and one large” was already established by the Hu administration, although its institutionalization and implementation varied across firms.Footnote 43 Party authorities at the time also suggested possible joint meetings between Party committees and boards of directors to discuss major issues, indicating that there was not yet a formal or well-established sequence of the Party committee first making decisions about major issues prior to board determination.Footnote 44

Party-building efforts

The Hu administration focused on broader Party-building efforts rather than targeted campaigns. Its primary goal was to strengthen the Party's governing ability by continuing Deng Xiaoping 邓小平 era reforms emphasizing clear rules and regulations as well as revitalization of the cadre corps.Footnote 45 Party-building efforts in SOEs under Hu included a variety of activities, such as Party-organized study sessions, circulation of policy texts and important speeches by senior leaders, study of the Party's positive traditions and style, as well as more pointed “warning education” (jingshi jiaoyu 警示教育) featuring examples of individuals or organizations that had strayed from the Party path.

The Hu administration did not launch a major central campaign to address official corruption in the state sector, even as official and public concerns about it steadily grew. Instead, the Hu administration's efforts to fight graft in SOEs through campaigns were more limited in scope and often integrated with broader Party-building initiatives.Footnote 46 The Party's Central Commission for Discipline and Inspection (CCDI), while an active and important body, was not the muscular political and policy actor that it would later become under Xi. Only two top executives of core central SOEs were investigated and subsequently formally removed on corruption charges under Hu – far fewer than the 12 top executives later removed under Xi.

Spiralling out of control

SASAC's deficiencies became increasingly apparent in Hu's second term. Its early struggles to command the state sector were clearest in its inability to wrest dividends from profitable SOEs.Footnote 47 SASAC also struggled to confine SOE operations to core business areas. In 2003, SASAC assumed primary responsibility for implementing the Hu administration's reform policy of “adjusting the layout of the state sector” (guoyou jingji buju tiaozheng 国有经济布局调整), a continuation of earlier efforts to concentrate state ownership in priority industries and withdraw from others. SASAC directed SOEs to declare a maximum of three main industries and confine their business activities within them. While SASAC publicly proclaimed major progress in reining in state firms’ sprawl, an internal report acknowledged that central SOE subsidiaries were “too broadly” dispersed and remained active in 86 of China's 95 official industries.Footnote 48

In the latter years of the Hu administration, central SOE involvement in urban real estate markets stirred major public controversy. After the global financial crisis, several central SOEs drew criticism in the press for their prominent role in high-profile land auctions in China.Footnote 49 In an effort to address mounting public dissatisfaction with SOEs’ part in driving urban housing prices sky high, SASAC tried to force 78 central SOEs to sell off their real estate assets, but with limited success.

At the close of the Hu administration, the challenge of making SOEs both market competitive and obeisant to the Party was plain to see. China's SOEs had ascended the ranks of the Fortune Global 500, a key metric of success in “going big and strong” in international markets: 62 Chinese SOEs made the list in 2012, compared to only 14 in 2005.Footnote 50 Approximately one-fifth of central SOE assets were now located overseas, with a value of approximately 5 trillion yuan.Footnote 51 The party-state had only weak capacity to “steer” SOEs that had become larger, more powerful and more publicly controversial than ever before.Footnote 52

Partying It Up: Xi Jinping's Governance Approach

The Xi administration (2012 to the present day) has remained committed to the vision of state ownership 2.0. SOEs are incentivized to keep “going out” through initiatives such as the Belt and Road Initiative and Made in China 2025. The Xi administration has also continued efforts to anchor state guidance of strategic sectors, such as high-speed rail and advanced manufacturing, in both domestic and global marketplaces. In addition, Xi-era initiatives to reduce SOEs’ administrative layers and holdings outside of their main industries further advance the concentration of state ownership.Footnote 53

Faced with SASAC's struggles to govern SOEs, Xi has formalized and strengthened Party control mechanisms. Xi redesigned the bureaucracy responsible for SOE governance by initially shifting the formulation of SOE governance priorities towards a leading small group and away from SASAC. His administration has also made somewhat greater use of leadership rotation and joint appointments. In addition, the Xi administration has institutionalized a stronger leadership role for Party organizations, including SOE Party committees, in state sector governance. Xi's far-reaching anti-corruption campaign, which targets SOEs, has also been an important means of increasing the CCP's capacity to steer the state-owned economy.

Bureaucratic design

Shortly after assuming leadership, Xi began to redesign the bureaucracy responsible for SOE governance. In 2013, he created the Central Leading Small Group (LSG) for Comprehensively Deepening Reforms (zhongyang quanmian shenhua gaige lingdao xiaozu 中央全面深化改革领导小组).Footnote 54 The staff office of the “Economic system” sub-group of this LSG, which Liu He 刘鹤 initially led, became the highest authority for crafting an SOE policy roadmap for the new administration: the 2015 “Guiding opinions of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and the State Council on deepening the reform of state-owned enterprises.” The Xi administration also established similar leading small groups for comprehensively deepening reform in the State Council and SASAC.

The central-level LSG, institutionalized in 2018 as the Central Comprehensively Deepening Reforms Commission, has side-lined SASAC's governance authority to a degree. Under Hu, SASAC led both the formulation and implementation of policies concerning SOEs, even if its tools of enforcement were inadequate. The creation of the Central LSG for Comprehensively Deepening Reform weakened SASAC's agenda-setting power. The LSG similarly diluted the authority of other actors like the National Development and Reform Commission and the Ministry of Finance by guiding and mediating their inputs into SOE reform policymaking. However, the LSG has become less active in SOE policymaking over time: it issued 12 policies referencing SOEs between its founding in 2013 and its institutionalization as a Commission in 2018, but only four since then.Footnote 55 The appointment of Hao Peng 郝鹏 as both SASAC director and Party secretary in 2019, thereby more clearly entrenching the Party's role, has further shifted the locus of policymaking and supervisory authority back towards SASAC.

The Xi administration also altered the organizational structure of SASAC itself. The State Council announced in 2018 that SASAC's supervisory board would be eliminated and its responsibilities and personnel transferred to the National Audit Office.Footnote 56 The State Council stated that this transfer of responsibilities would improve audit efficacy by avoiding duplicate inspections and streamlining supervisory authority.Footnote 57 In practice, however, the elimination of the supervisory board also cut away the contingent of former central SOE leaders who comprised much of its membership, thereby excising the body through which retirees continued to exercise political influence via SASAC.Footnote 58

Cadre management system

The Xi administration has employed leadership rotation and joint appointments more actively than the Hu administration to tighten its control over SOEs. For example, the Central Organization Department (COD) shuffled 19 core central SOE leaders to head other SOEs during Xi's first five-year term alone – an average transfer rate of 3.8 per year, compared with 1.4 for Hu. Whereas only one bilateral swap of top SOE leaders in a single sector happened under Hu, several such executive swaps have already occurred under Xi.

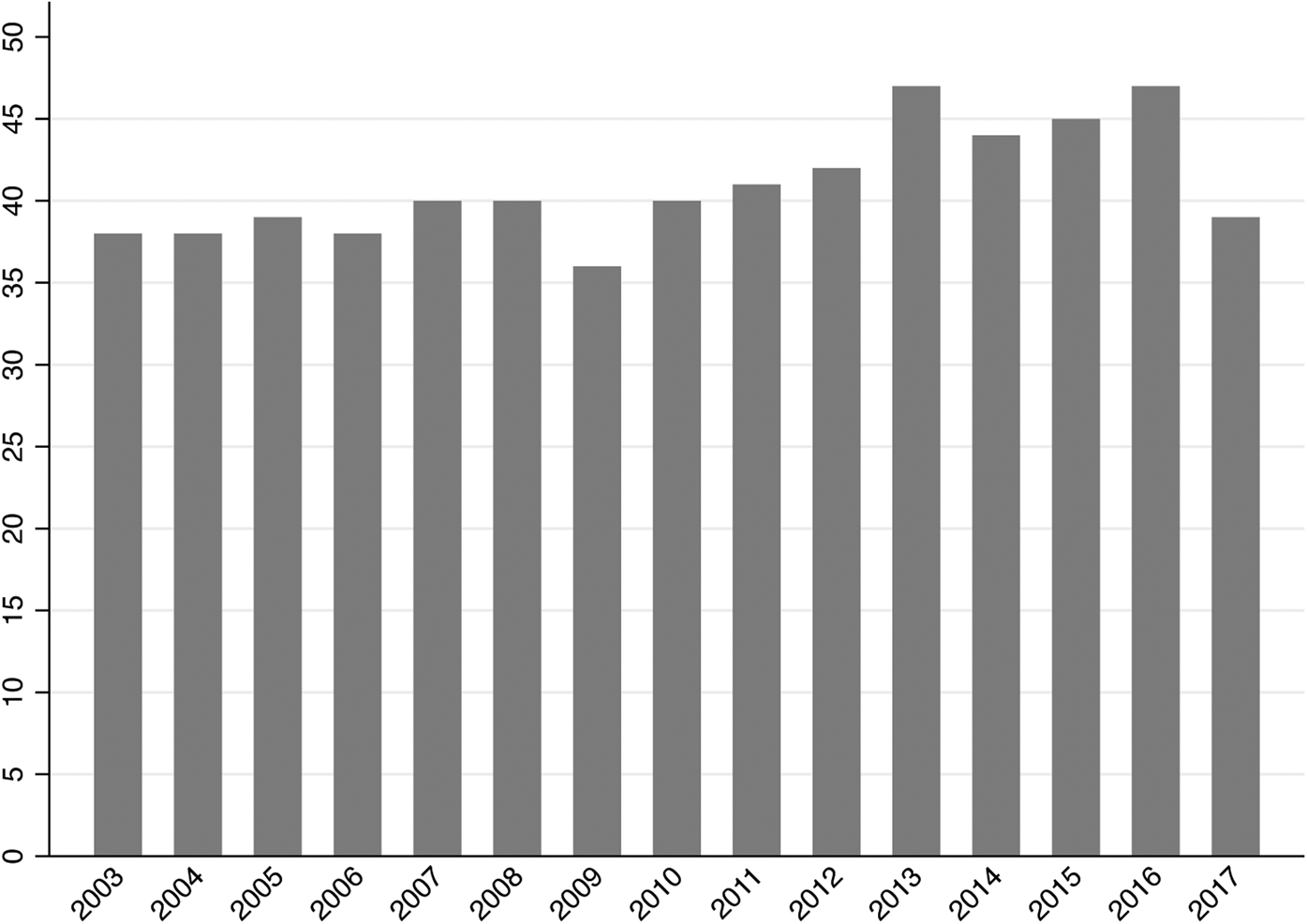

The practice of joint appointments for SOE leaders, already common under Hu, has increased further under Xi (Figure 1). Among core central SOEs, for example, the average incidence of any combination of joint appointments was 89 per cent during Xi's first five-year term, up from 76 per cent during the Hu administration. One person acted as both board chairman and Party secretary in more than 90 per cent of firms.Footnote 59 In 2015, the Xi administration issued policy guidance formally requiring the joint appointment of Party secretary–board chairman posts in SOEs.Footnote 60 In 2016, SASAC announced that central SOEs would fully implement this joint appointment policy beginning in 2017.

Figure 1: Joint Appointments for Top Executive Positions in Core Central SOEs, 2003–2017

Source:

Authors’ data.

Notes:

This figure shows all individuals holding two or more of the three top leadership positions – Party secretary, general manager or chairman of the board of directors – for at least six months.

The Xi administration has also employed joint appointments for SASAC's leadership for the first time. Ever since SASAC's creation in 2003, separate individuals have always held the positions of director and Party secretary, except in cases of exigency. In 2019, however, the-then SASAC Party secretary Hao Peng was appointed to serve simultaneously as director.Footnote 61 It is also notable that subsequent major announcements by SASAC leadership have been made at meetings of the Party committee instead of the general office as in past practice.Footnote 62 Today, the two entities appear to have actually become one and the same: they have a single official website under the name “SASAC Office (Party Committee Office).”Footnote 63 Having failed to govern the state-owned economy effectively through Hu-era bureaucratic design, Xi has invested SASAC with stronger Party authority in the hope that this will provide the necessary muscle to command SOEs.

In addition, the Xi administration has implemented a new policy of “lifetime accountability” for SOE leaders. The 2014 Fourth Plenum proposed the concept of “lifetime accountability” (zhongshen zeren zhuijiu zhidu 终身责任追究制度) for major investment and operational decisions by leading officials in the public sector.Footnote 64 The State Council subsequently established a lifetime accountability system for SOE leaders in 2016. Any SOE leader who violates regulations, causes the loss of state-owned assets or any other “serious adverse consequences” can in theory be held legally liable until death for any such behaviour or decisions during their leadership tenures.Footnote 65 Although this policy has yet to be widely implemented, it adds to the growing scrutiny of SOE leaders at both central and local levels.Footnote 66

Party organizations

The Xi administration has institutionalized the Party's “leadership role” in SOE governance. It has directed SOEs to make the Party the “political core” of their corporate governance and formalized the long-standing practice of Party committees discussing “major decisions” before they go to boards of directors for final determination.Footnote 67 It has further ordered SOEs to revise their corporate charters to legalize requirements for Party-building work and the Party committee's leadership role in corporate governance. By 2017, SASAC announced that all central SOEs had done so, although Party-related amendments differ significantly in content and time of adoption.Footnote 68 Of companies publicly traded in Shanghai and Shenzhen, 30 per cent amended their corporate charters between 2015 and 2018, the majority of them state-owned firms.Footnote 69 Revision of corporate charters is a clear signal of Xi's intent to deepen Party influence, but one that builds incrementally on existing practice and the foundations of Party-building established by his predecessors.

The Xi administration has also revised the CCP constitution to enshrine Party authority in SOE governance. The Xi regime formally specified the Party committee's authority to “play a leadership role” (fahui lingdao zuoyong 发挥领导作用) in SOE decision making by adding this language to the Party Constitution at the 19th National Party Congress in 2017. While largely symbolic, this move underscores the Xi administration's prioritization of Party control and its concerted efforts to amplify and institutionalize the CCP's influence in corporate decision making.

While Xi's governance formula relies more heavily on Party control mechanisms than his predecessor's did, there is also evidence of continuity from the Hu administration in officials’ views of the Party's role in SOE governance. Content analysis of the official releases on SASAC directors’ annual work reports do not exhibit sharp divergence in the frequency of references to “Party,” “Party-building” and “Party leadership” under Hu and Xi. This underscores that Party guidance was also a priority under Hu and is itself not a differentiating characteristic of Xi's administration (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Party References in Official Releases on SASAC Directors' Speeches to the Annual Central SOE Leaders’ Conference

Source:

Authors’ data.

In fact, average mentions of “Party” were actually slightly higher from 2003 to 2012 (41) than from 2013 to 2020 (36). Peak references to Party building came towards the end of the Hu era, in 2009 and 2010. Party leadership was also a part of official SASAC vocabulary in both periods, although the phrase has appeared more often since the 19th Party Congress in 2017.

Campaigns

Xi launched a far-reaching anti-corruption campaign in 2013 that quickly made SOEs a top target. The CCDI conducted three waves of inspections targeting the core central SOEs: at 2 firms in 2013, 10 firms in 2014, and 43 firms in 2015. By the end of Xi's first five years in office in 2017, 12 top executives from core central SOEs had fallen on corruption charges.Footnote 70 The CCDI launched another round of anti-graft inspections in 2019, targeting 42 firms among all central SOEs as well as SASAC. It ordered a total of 7,597 rectification measures for the 42 firms and 208 for SASAC, with 7,192 and 147 of those respectively deemed successfully completed as of March 2020.Footnote 71

SASAC's poor record in controlling graft during the Hu administration provided a rationale for the Xi administration to turn away from the government towards the Party to fulfil monitoring functions. Xi's anti-corruption campaign operates through the Party bureaucracy and outside of the existing systems of governance in both SASAC and SOEs. Implementation by external Party authorities, in coordination with internal actors, and harsh punishments may catalyse broad compliance as long as the campaign continues. However, it has limited ability to facilitate long-term structural changes in SOE auditing, information reporting and transparency.

SOE Governance under Xi and Its Consequences

In contrast to departure narratives, our analysis of SOE governance under Hu and Xi reveals deepening Party control rather than a decisive departure from past practice. The core goal of moulding SOEs that are both market competitive and obedient to the Party has remained consistent across both administrations. Under Xi, the balance struck between these two objectives has shifted towards Party obedience, but market competitiveness remains a vital aim. Furthermore, the Xi administration has brought to bear the same toolkit as its predecessors – bureaucratic design, the cadre management system, Party organizations and campaigns – while relying more heavily on Party-centred command and control.

Beyond the four governance mechanisms examined in this article, other empirical evidence supports a deepening narrative. The proportion of central SOE leaders who were simultaneously CCP Central Committee members at the beginning of the Xi administration was in the single-digits and actually slightly less than Hu-period peaks, thus providing little evidence of departure.Footnote 72 In addition, the share of SOEs in China's economy has remained remarkably stable for nearly a quarter of a century, at about 25 per cent of GDP, suggesting that a definitive “advance of the state” has not occurred under Xi.Footnote 73 Nor does departure appear evident in the private sector, with recent research similarly finding that Xi's policies do not diverge fundamentally from those of his predecessors.Footnote 74

Furthermore, it may be premature to make claims about what is really new in the “Xi era.” Analysis of intra-administration variation over time could prove especially important in this case, because the removal of term limits for Xi's position as CCP general secretary in 2018 means that he may hold on to power after the next Party Congress in 2022.Footnote 75 Taking a new “Xi era” as the discrete unit of analysis may therefore obscure important temporal variation in the Xi administration's vision for a particular policy area, which tools of governance it deploys to achieve it, and what outcomes result. Instead, closely examining trends over time in specific areas, as done here with regard to governance of the state-owned economy, enables identification of intra-regime variation as well as potential continuities with previous administrations’ practice.

Even incremental deepening of Party control over the state sector has important domestic consequences. In a process that Barry Naughton terms “grand steerage,” the Party increasingly behaves like a hedge fund manager or venture capitalist by directing SOE commercial activities, including research and development, in key sectors and technologies like new energy, digital and quantum technologies, artificial intelligence and facial recognition.Footnote 76 Although winning even one of these “bets” would yield huge commercial and strategic payoffs, the Party's efforts to steer the economy do not guarantee smooth sailing. The CCP still struggles to exercise control over increasingly wealthy and savvy firms and to avoid industrial policy missteps.

Deepening of Party control also affects company decision making and behaviour. Legal changes to company articles of association enshrine existing Party objectives and influence in SOE missions. Although the Xi administration contends that greater Party control will yield enterprise efficiency and performance gains, there is, to date, little empirical evidence to support this. On the contrary, decreasing enterprise autonomy in service of strategic objectives could introduce inefficiencies and incur real-world costs. Such commercial trade-offs vary in their scale and scope, ranging from unprofitable overseas investments like mineral assets in Australia to government-directed mass hiring of Chinese university graduates to shore up social stability after COVID 19-induced economic slowdown.Footnote 77 Yet pursuit of political and social objectives at the price of economic performance has characterized Chinese SOE operations for decades. Even if such economic trade-offs are more acute under Xi, both SOEs and the state still have the financial resources to permit and sustain them.

Enhanced CCP control over SOEs also has significant international ramifications. Perceptions that the Communist Party is too close to Chinese firms’ decision making has prompted stronger foreign direct investment screening mechanisms in the United States and European Union.Footnote 78 Along with domestic restrictions, higher barriers abroad have contributed to a steep decline in Chinese outward investment since 2016.Footnote 79 In the longer term, substantial cooling under Xi of economic and political relations with the United States and other countries is already prompting debate about potential future “decoupling.”Footnote 80

Conclusion

What is new in Xi Jinping's governance of the state-owned economy? Contrary to claims that Xi has ushered in a new era, we find evidence of significant continuity with the Hu administration. Both leaders subscribe to the vision of state ownership 2.0. While the Hu administration leaned more heavily on the state bureaucracy to deliver results, Xi has instead made greater use of Party-centred control mechanisms. Although Party governance tools have been formalized and sharpened under Xi, current SOE governance is, to a large degree, inherited from previous administrations.

Our paper also provides a framework for evaluating claims of era change across issue areas. A key task is to establish what decision makers themselves envision as the goals of reform: what do they hope to achieve? And how has this changed over time? Making empirically robust claims of era change entails, first, identifying leaders’ policy visions and, second, tracking changes over time in discrete issue areas. This work is essential to accurately interpret facts on the ground. As Sebastian Heilmann and Oliver Melton argue, the “plan to market” narrative of economic reform common in earlier scholarship was not mirrored in Chinese leaders’ own conviction that economic transformation had to be strongly state led.Footnote 81 As such, the fact that the party-state retains a highly interventionist role in the economy is neither surprising nor, in itself, evidence of a new era. Second, in keeping with Sebastian Heilmann and Elizabeth J. Perry's observation about the persistence of revolutionary and Mao-era governance techniques after 1978, tracking change in governance tools across time is also critical to the definition and differentiation of eras.Footnote 82 In all, observers may legitimately critique the direction of state-owned economy governance under Xi Jinping, but that does not necessarily mean that either the aims or means of governance are new.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Nis Grünberg, Patricia Thornton and two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments. They are also grateful to Lejie Zeng for research assistance.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Biographical note

Wendy LEUTERT is GLP-Ming Z. Mei chair of Chinese economics and trade at Indiana University's Hamilton Lugar School of Global and International Studies and the department of East Asian languages and cultures.

Sarah EATON is professor of transregional China studies at Humboldt University Berlin.