Scholars of Chinese politics have long been concerned with which factors play a more critical role in the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) regime's political selection process. Evidence from various administrative levels yields conflicting results. At the state level, factional and patron–client ties with state leaders tend to outweigh economic growth performance in determining elite cadres’ promotional chances.Footnote 1 Findings at the provincial level are mixed. Some show that good economic performance increases provincial leaders’ likelihood of promotion. Others indicate that factional ties overshadow performance-based criteria.Footnote 2 Some studies argue that provincial cadres need both patronage ties and good performance to achieve promotion.Footnote 3 Research at the prefecture and county levels also reveals a complex picture: economic performance seems to boost the probability of promotion in some studies but not in others. More recent findings point to the connection between patronage ties and performance, suggesting the co-dependence of the two factors in predicting promotional prospects.Footnote 4 Puzzled by the inconsistent evidence from across the Chinese political hierarchy, scholars compare cadres from provincial, prefectural and county levels and reveal a “dualist strategy” of political selection in China. Competence measured by economic performance is essential for cadres at the lower level of the administrative hierarchy owing to the state's need to maintain performance legitimacy. At the same time, patronage connections become more crucial at higher levels as the regime seeks to ensure the allegiance of its core state elites.Footnote 5

The literature on cadre promotion shows a puzzling lack of attention to the loyalty-inducing Party institution's role in the promotion process. Few researchers who recognize the inconsistencies in the findings on promotional prospects propose other mechanisms to account for the regime's effort to balance political control and legitimacy. Pang Baoqing and colleagues characterize the political selection research agenda as a false dichotomy between an under-institutionalized and over-institutionalized perspective on Chinese politics: the former overemphasizes political control, the latter overemphasizes political legitimacy. Nevertheless, both camps overlook the fact that both elements are equally crucial for authoritarian regime survival.Footnote 6 Their study of the dual-track promotion system points to China's “selective institutionalization” that emphasizes both control and legitimacy. On the one hand, the state utilizes institutionalized promotion criteria such as competence to motivate cadres in achieving performance goals. On the other hand, cadres trained by Party schools are on a faster track to promotion than those without such experience, indicating a de facto “violation” of the Party's cadre promotion institution.Footnote 7 Charlotte Lee's study on “party-sponsored upward mobility” suggests that Party school training contributes to cadre promotion.Footnote 8 These observations add to the understanding of the political selection process because they emphasize the cadre management system's crucial role in the promotion process.Footnote 9 Unfortunately, the effect of loyalty-inducing Party institutions on promotion has only been tested at the prefecture level. Given the potentially different promotion logic between different administrative levels, it is unclear if the effect will be observed across the bureaucratic hierarchy. The current study intends to test such an institution's impact on cadre promotion at the Chinese administration's lower level.

This study's empirical analyses are based on an original survey dataset of China's township and county-level cadre training records. The dataset also permits the use of an alternative measure – university training experience – to account for local cadres’ competence. By applying a rigorous data-processing method – coarsened exact matching (CEM) – the causal effect of cadre training on local political selection can be further explored. This paper finds that loyalty – accounted for by cadres’ training experience at Party schools – significantly increases township cadres’ probability of being promoted to the county level. In particular, township-level cadres trained by Party schools have an 8 per cent higher likelihood of being promoted to county-level than cadres who have not been trained by Party schools. Cadres trained by universities are 5 per cent more likely to be promoted than those without such experience. In other words, Party school training has a 60 per cent greater impact on local cadre promotion than does university training. This finding indicates that loyalty indeed contributes to promotion at the lower administrative level, and such effects may even outweigh cadres’ competence. On the other hand, further analysis shows that even loyal cadres need competence to be promoted in practice. Those who are both trained by Party school and university – in other words, both loyal and competent – are the most competitive group among local cadres.

Operationalizing Loyalty and Competence at the Local Level

Promotion patterns of cadres below the county level remain underexplored, and rarely has any quantitative evidence been presented for the township level. This lack of quantitative research on one of the largest cadre groups in the Chinese administration can be partially attributed to limited data availability at the lower government levels. The common operationalization of the explanatory variables used in promotion literature, such as patronage ties and competence, becomes an impossible task with the large population of township cadres. This challenge leads to an abundance of qualitative case studies but not quantitative research at this level.Footnote 10 Here, I present this study's operationalization of loyalty and competence at the local level based on existing research and my fieldwork.

Scholars have identified Party school training as an essential factor in cadre promotion in addition to personalist patronage and competence. For example, Lee's research demonstrates that cadres trained in Party schools are 15 per cent more likely to be promoted than cadres without such training.Footnote 11 Pang, Keng and Zhong also contend that Party school training contributes to faster promotion for prefecture cadres.Footnote 12 Inspired by the existing research approach, I use local cadres’ Party school training experience to account for their loyalty to the CCP regime. Extant studies indicate that Party schools are crucial for cultivating cadres’ allegiance and strengthening the regime's influence over its agents.Footnote 13 The Party school network, which is the core apparatus for cadre training in China, is regarded by scholars of Chinese politics as “one of the most important, but under-researched and least well understood” institutional designs of the CCP regime.Footnote 14 David Shambaugh defines the Party school apparatus as “an important institutional agent for conveying ideology and policy reforms to cadres.”Footnote 15 An ethnographic study of a local Party school in Yunnan province by Frank Pieke and Eryu Duan also concludes that “the main mission of training remains Leninist ‘unification of thought’.”Footnote 16 As shown in Table 1, most of the content in a typical Party school training programme focuses on ideological and CCP political theory education. This accords with the recent stipulation that theoretical education and Party character education must account for no less than 70 per of course hours.Footnote 17 Party school training, therefore, serves as a reliable indicator of cadres’ loyalty to the regime.Footnote 18

Table 1: Curriculum of a Township-level Young Cadre Training Programme at a Provincial Party School

Source: Author's fieldwork, Beijing, 2019.

In addition to the listed courses, cadre training programmes in Party schools are equipped with various mechanisms to inculcate loyalty and monitor cadres’ learning progress. For example, other than recorded course attendance, group discussions on experiences of exemplary political leaders and cadres and team-building exercises at sites of revolutionary importance in Party history (for example, the Jinggang Mountains 井冈山 revolutionary base) are frequently scheduled. In addition, at the end of training sessions, cadre trainees must write an essay (typically around 3,000 words) about how the training helped them to develop a collective identity. This substantive group-focused and group identity-building training content serves as a critical additional mechanism in loyalty cultivation.

Conventional measures of competence in the promotion literature, such as local GDP growth, can be applicable for higher government levels but are insufficient to capture the comprehensive performance criteria for township cadre evaluation.Footnote 19 Township cadres are at the frontline of state policy implementation at the local level.Footnote 20 Beyond generating economic growth, they are also responsible for other crucial tasks at the grassroots level such as Party building, education promotion, family planning and maintaining public order, tasks which are not necessarily welcomed by citizens.Footnote 21 For example, according to Wenjia Zhuang and Feng Chen's study on local labour dispute resolution, 17 per cent of labour disputes in 2010 were mediated by township cadres, significantly higher than the 6 per cent managed by village agencies and 5 per cent undertaken by county cadres.Footnote 22 Research on the one-child policy shows that the implementation of family planning policy at the township level contributes to many “incidents of revenge,” which are certainly not conducive to township cadres’ career advancement.Footnote 23 In township cadre evaluation, the failure to fulfil priority tasks such as maintaining social order renders performance in other fields pointless.Footnote 24 The accountability of township cadres to both upper-level government and grassroots citizens implies that economic growth alone is an inadequate criterion to measure township cadres’ competence, both in the theoretical and practical sense.Footnote 25

Accordingly, this study utilizes an alternative measure – whether a cadre has training experience at academic institutions – as a proxy to account for local cadres’ competence.Footnote 26 The assumption is that township cadres with training experience in universities will have a better understanding of policy and an enhanced skillset regarding various governance issues than those without such training. It follows that trained cadres will be more competent and perform better than untrained cadres. Furthermore, unlike Party school training, where trainees have less control over what courses they receive, university training flexibly caters to cadres’ learning needs by designing course content according to their requirements. For example, according to a training contract between the department of organization and human resources in City C and University Z, “Party A (the university) is responsible for curriculum design, textbook choice, and instructor assignment – based on the government department's needs and requirements; Party B (the government department) proposes suggestions and requirements for the curriculum design and participates in the process of designing the training programme and teaching plan.”Footnote 27 Given such an opportunity, it is likely that cadres will request courses that can provide explanations and solutions for hard-to-solve problems that may negatively affect their performance, or seminars that interpret newly issued policies that are relevant to their policy implementation.

An analysis of the content and focus of the university training curricula provides suggestive evidence for this mechanism. As shown in Table 2, a university cadre training programme is packed with practical policy interpretation and implementation information. Most university training sessions share a similar structure. According to some instructors, local cadres are in dire need of such knowledge. Many cadres with lower education levels are not confident in interpreting and implementing complex policy reforms at the local level. Moreover, the frequency at which higher government issues policy mandates, along with ever-changing local conditions, makes it increasingly challenging for cadres to keep up with all the policy reforms.Footnote 28 For example, after the central government issued the national supervision system's reform plan in 2017, the number of university training courses focusing on this reform surged as cadres from all over the country enrolled into such training sessions to learn how to implement this reform at the local level properly. In other words, university training serves as an essential channel through which local cadres can update their knowledge on recent policy reforms and governing strategies.

Table 2: Curriculum of an 18-day Cadre Training Programme at University Z

Source: Author's fieldwork, Beijing, 2019.

The curriculum in Table 2 also provides evidence that university training experience can account for cadres’ competence in a way that speaks to the traditional measure of merit – economic performance. This training programme includes many courses on local economic development such as the management of local small and medium-sized enterprises, tax reform, government debt and budget management.Footnote 29 The programme also covers various topics crucial for other aspects of local administration such as social governance strategies at the local level and the application of new technology to innovative local government management. To some extent, this content reflects the comprehensive knowledge and skills local cadres are expected to master, especially in fields related to local economic development.Footnote 30 It also points to one of the potential sources of local cadres’ capability to deal with complex governance issues while still promoting the local economy. The common operationalization of cadre merit – local economic growth – overlooks the complexity of successful local governance. In comparison, the competence represented by university training emphasizes individual cadres’ knowledge base, their comprehensive governance ability and their capability to promote the local economy. It thus serves as a reasonable substitution for the traditional measurement of competence at the local level.

Admittedly, how much effect university training has on cadres’ actual performance is impossible to measure. While the efficacy of training is hard to evaluate in practice, some circumstantial evidence suggests that university training tends to enhance local cadres’ competence. First, on-site observations of the interactions between cadre trainees and instructors during fieldwork finds that cadres highly respect their instructors’ expertise and pay significant attention to the course content. They are also eager to consult instructors about policy interpretations and specific problems they encounter in their work. A high level of cadre–instructor interaction suggests that this learning experience is likely to contribute to cadres’ understanding of policy implementation, at least to some extent.

Second, many instructors voluntarily share their personal contact information with cadre trainees and explicitly recommend that they reach out when they encounter questions at work that lie within the instructors’ expertise. For example, during a training session, a law professor shared several stories of past trainees who sought expert help from him long after attending his course. This post-training interaction provides suggestive evidence that university training's impact on cadre competence could extend well beyond the training session itself. Even after training, cadres can still be “tutored” by experts. Such a fringe benefit is certainly unavailable for cadres who have not participated in university training.

Third, cadres’ feedback on training programmes also indicates that they perceive university training as a means to increase their competence, especially for potentially disadvantaged cadre groups. For example, the following comment on university training from a cadre trainee indicates that cadres from underdeveloped regions are in desperate need of such competence-advancement opportunities:

Training needs to be deepened. As a cadre who has participated in the workforce for ten years, this is the first time I can participate in training at this level/rank. Therefore, I suggest that in future training plans, cadres at the county and township level should have more training, which gives grassroots cadres from the remote mountain area an opportunity to expand their horizons and think of the bigger picture.Footnote 31

While university training focuses primarily on the “competence” aspect, such focus is not exclusive. For instance, it is common for university training programmes to include courses that explore communist and Marxist ideology, such as the “Scientific world view and methodology” course in the university training curriculum (see Table 2) or the interpretation of President Xi Jinping's governing principles. Similarly, Party school training programmes also frequently include courses that aim to improve cadres’ competence, such as the “Promote the transformation and upgrading of the local economy, and the innovation of local governance” course listed in Table 1. Neither the “loyalty” nor “competence” component is utterly absent in either type of training; however, the structures of the training curricula offered by Party school and university training clearly indicate that their primary focus is loyalty and competence, respectively.

The above discussion on the potential effect of both loyalty and competence on promotion, as well as the operationalization of loyalty and competence at the local level, leads to the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1: all else being equal, township cadres with Party school training will have a higher probability of being promoted to county-level posts than those without such training experience.

Hypothesis 2: all else being equal, township cadres with university training will have a higher probability of being promoted to county-level posts than those without such training experience.

Data and Methodology

This study tests the above hypotheses using a unique original dataset of cadre training records based on an anonymous survey conducted by a Beijing university that hosts cadre training programmes.Footnote 32 The survey asked training participants for demographical information and past training experience gained in different institutions as well as training and work-related questions. Participants in these training programmes held county-level and township-level administrative positions. As trainees came from all over China, the survey was able to cover cadres from 26 different provinces, autonomous regions and municipalities. Thus, the dataset reasonably represents cadres from various localities in China but does not statistically represent the entire local cadre population. Furthermore, while a cadre training sample gathered by a Party school may differ from a sample collected in a university setting, there is no empirical evidence proving different cadre composition in university and Party school training. Therefore, the relationships between the key variables should not be affected by the sample source, even if the overall levels of the critical variables may depend on the sample source.

The dependent variable of interest is local cadre promotion, a dichotomous variable with 1 representing cadres promoted from township level to county level, and 0 representing those who did not get a promotion. Note that the precise point in time when an individual cadre was promoted was unavailable owing to limitations in data availability. This lack of information makes it difficult to account for variables such as the time it takes to achieve promotion, which is shown to be important for promotion at and above the county level, and there is an absence of empirical evidence for cadres below the county level.Footnote 33 On the other hand, survey respondents listed training activities they had undergone prior to promotion, which enables this study to establish training as an ex-ante indicator of promotion prospects without knowing the exact timing of promotion. The empirical analysis in this study focuses on the single-level career change from township to county level rather than on the promotion literature's typical measurement of promotion from various lower-level ranks to various higher administrative levels. Unlike some studies that do not explicitly assume a difference in promotion mechanisms between different bureaucratic levels, this study intends to distinguish local cadre promotion mechanisms from those promoting higher-level elite cadres.Footnote 34

Party school training and university training are binary variables where 1 represents those with training experience, and 0 represents those without training experience. Table 3 presents the summary statistics of other relevant variables in the local cadre training dataset. Compared to township-level cadres, county-level cadres in the dataset tend to be older, male, members of the CCP, have higher education levels, have received more Party school and university training, and interact with their peer colleagues more frequently. Considering that the highest standard deviation for a 1/0 binary variable is 0.5, the summary statistics indicate that many of the binary variables have a near-maximum standard deviation, all of which vary meaningfully.

Table 3: Summary Statistics of Local Cadres

The above variables are controlled in the statistical analysis to reduce estimation bias. Since the survey did not ask about the time it took for cadres to reach their current rank, age is controlled instead. Education is a four-category variable that includes below college level, college degree, master's degree and Ph.D. degree. CCP membership is coded as 0 for non-CCP members and 1 for CCP members. This variable is included because, unlike most elite cadres, some local cadres are non-CCP members. In this dataset, 18.65 per cent of cadres are non-CCP members. This factor may influence the probability of their promotion if CCP membership indicates a closer affiliation with the regime and works as an advantage in the promotion process. Additionally, given the diversity between Chinese localities and its possible influence on promotion prospects, spatial variation is controlled by including cadres’ home provinces as dummies.

According to the promotion literature, factional or personalist patronage ties and peer competition are also important influencers.Footnote 35 Unfortunately, patronage ties at the local level are next to impossible to observe, and recent research shows that this factor may not matter for promotion at the local level.Footnote 36 Similarly, unlike peer competition among elite cadres, which can be measured by counting the potential competitors at the same administrative level such as provinces or prefectures, local cadres may have too many potential competitors to be measured in this way. Accordingly, this study uses training participants’ reported frequency of interaction with their peers and leaders at a higher administrative level as proxies to account for local cadres’ relationships with their peers and supervisors.Footnote 37

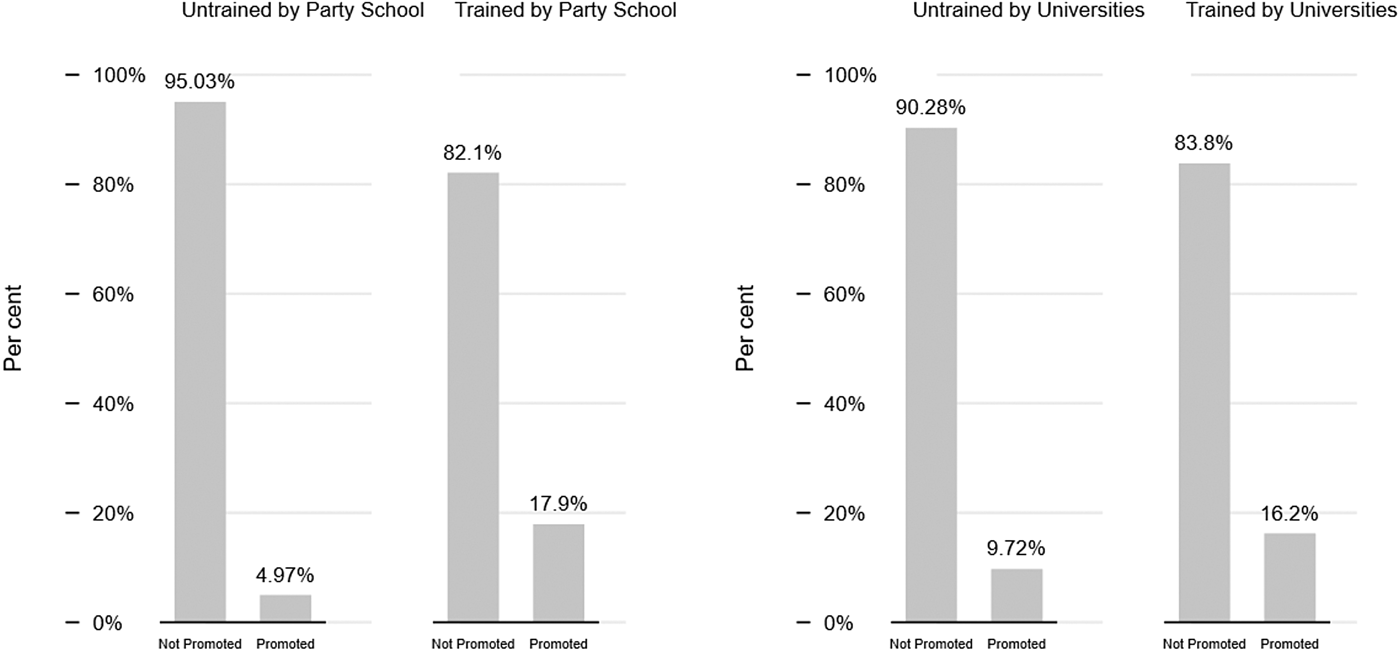

This study's primary concern is the relationship between different types of training experiences and local cadre promotion. As shown in Figure 1, there are different promotion patterns for different kinds of training. The percentage of cadres who were not promoted seems higher for groups with no training experience, indicating a possible conducive effect on promotion. The difference between cadres who underwent Party school training and were promoted versus those who were promoted without such training is 12.93 per cent. For university training, the difference is 6.48 per cent. These descriptive statistics indicate that Party school training may have greater impact than university training on local cadre promotion. However, this distribution cannot yet prove the causal link between cadre training and promotion. Further analysis controlling for relevant factors that may influence such a relationship is needed. Ideally, an experimental setting with cadre training as the “treatment” on the promotion outcome can best predict such a causal relationship.

Figure 1: Local Cadre Promotion by Training

Previous research using survey data to explore the effect of Party school training on cadre promotion has adopted one of the most popular matching methods, propensity score matching (PSM), to address the counterfactual question of whether a cadre in the “treated” group with Party school experience is more likely to be promoted than a cadre in the “control” group without such experience.Footnote 38 However, the PSM method has recently been challenged by scholars whose research indicates that PSM could increase the imbalance in the data structure and lead to model dependence and biased estimation.Footnote 39 Coarsened Exact Matching (CEM), on the other hand, offers an alternative method to reduce data imbalance and model dependence in observational data. Accordingly, this study evaluates the results of various matching methods for the local cadre training dataset and adopts a combination of different approaches to achieve the best matching results.Footnote 40 Admittedly, scholars can never be sure that endogeneity is not a problem with observational data. However, the variables that are matched on/controlled for can help to address imbalances in unobservable factors such as pre-existing guanxi 关系 in influencing cadre promotion (the relevant proxy is the “superior interaction” variable in this case). For example, doing so enables us to estimate whether a cadre with Party school training experience would be more likely to be promoted in the unobservable scenario where that same cadre did not have Party school training experience.

The propensity score distribution of pre-matching, PSM-only matching, CEM-only matching, and a combination of CEM and PSM matching are illustrated in Figure 2. The use of any matching method significantly reduces imbalance in the original local cadre training dataset. While adopting either a PSM or CEM approach leads to almost identical matching results, a CEM matching followed by the PSM method performs best, largely reducing the imbalance in the propensity score distribution between treated and untreated groups. Therefore, the following empirical analysis of this study will be based on a combination of the CEM and PSM methods.

Figure 2: Density Distribution of Propensity Score under Different Matching Methods

Note that for most observational data, coarsening can significantly reduce imbalance but will not eliminate it. This potential problem speaks to the need to control for the remaining imbalance through a post-matching statistical model.Footnote 41 Since the dependent variable is measured dichotomously, this study estimates a series of logistic regression models to account for the impact of cadre training on the probability of local cadre promotion and the strength of such an effect when conditioned by other relevant factors.

Results

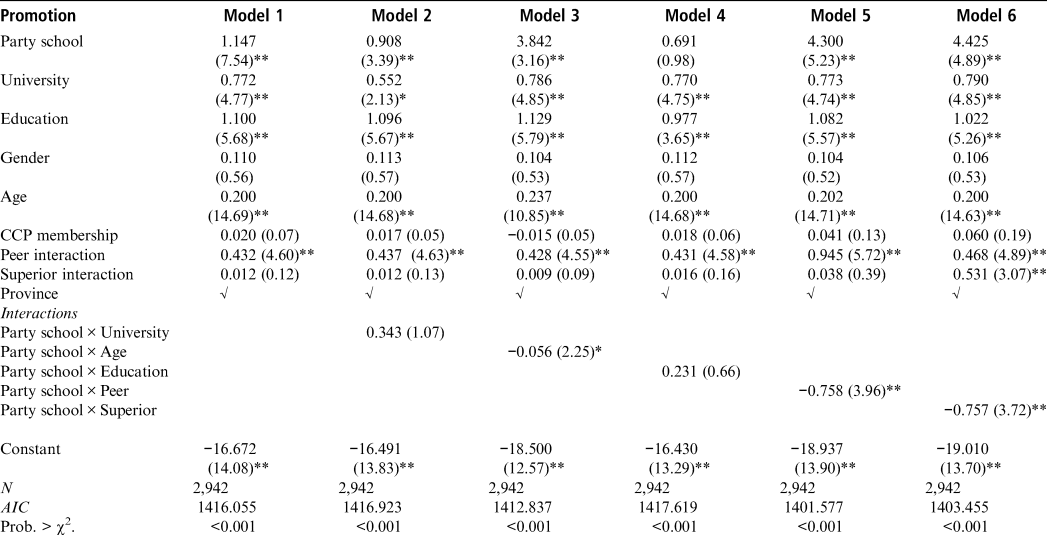

Table 4 presents a series of logistic regression models’ estimation results where the dependent variable is a promotion from township level to county level. Model 1 gives the primary model results without any interactions between covariates, and Model 2 presents the outcome of an interaction between Party school and university training. Models 3–6 explore the impact of cadre training on promotion conditioned by relevant variables. This study visualizes the empirical results for a more intuitive understanding of the treatment effects owing to the difference of interpretation between logistic regression and linear regression.

Table 4: Cadre Training and Local Cadre Promotion

Notes: Dependent variable is promotion. Results are from logistic regressions. Standard errors in parentheses. AIC = Akaike information criterion. * Significant at p < .05 (two-sided); ** Significant at p < .01 (two-sided).

The results of Model 1 provide support for the hypotheses that cadre training is conducive to local cadre promotion. The coefficients of Party school training and university training on promotion are positive, while the Party school training effect is stronger than the university training effect. These results indicate that cadres with any training experience are more likely to be promoted than those without training. On the other hand, township-level cadres with Party school training are more likely to be promoted to the county level than those trained by academic institutions.

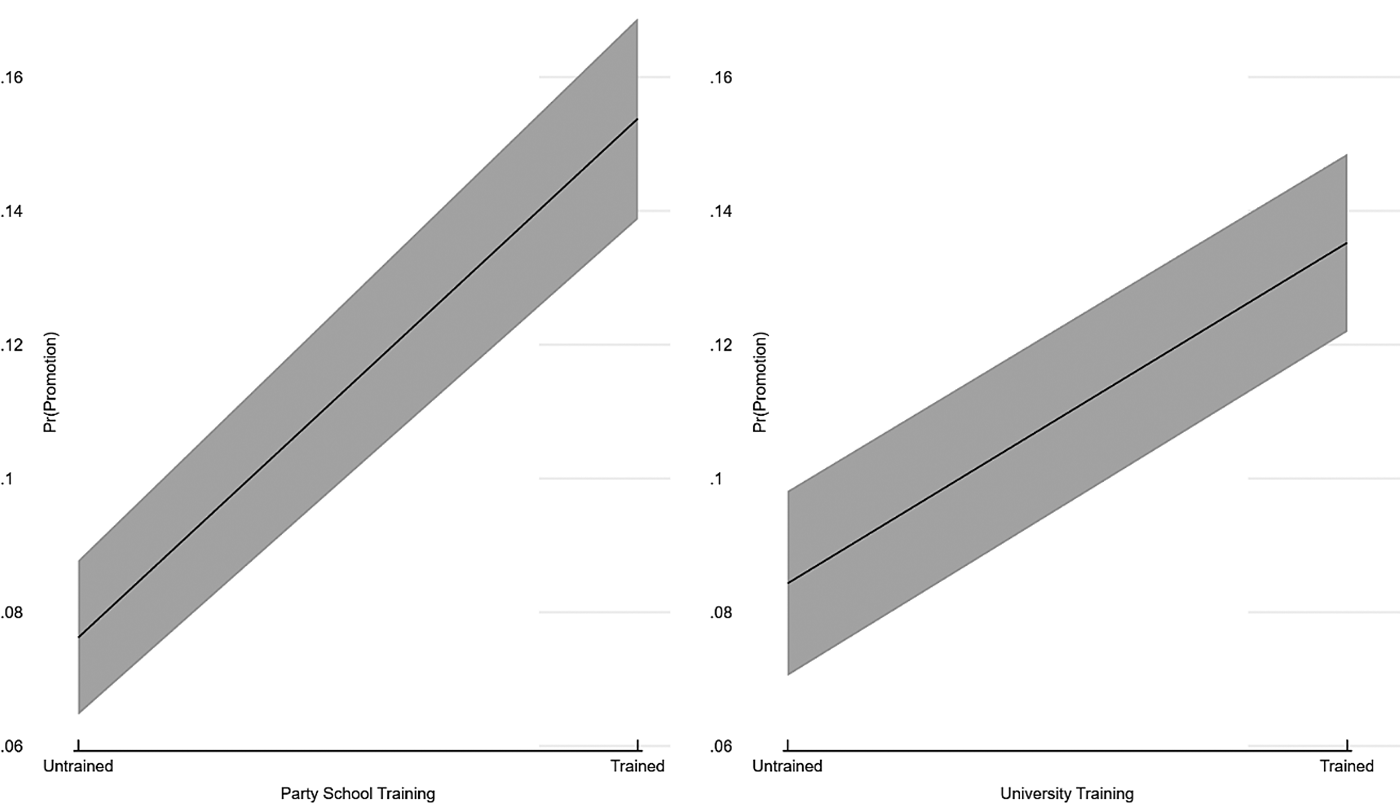

Figure 3 illustrates this effect. All else being equal, township-level cadres trained by Party schools are 8 per cent more likely to be promoted to county level than cadres not trained in Party schools. This effect is weaker than the 15 per cent advantage on the promotion of trained cadres found in Lee's study; however, her research does not focus exclusively on local cadre promotion from the township to the county levels.Footnote 42 Cadres trained by universities have a 5 per cent higher probability of being promoted than those without university training experience. In other words, Party school training has a 60 per cent greater impact than university training experience on local cadre promotion. This result implies that Party school training has more impact than university training on township cadres’ chances of promotion.

Figure 3: Effect of Cadre Training on the Predicted Probability of Local Cadre Promotion

Among the control variables in Model 1, education and age are significantly and positively correlated with promotion, which corroborates the role of professionalism and accumulative experience in gaining a promotion. Note, however, that the positive relationship between cadre age and promotion at the local level stands in contrast to the evidence for elite cadres such as those at the provincial and municipal levels.Footnote 43 This result makes sense given the difference in the mean age of different cadre groups, where provincial cadres in previous research have a mean age of 60. In contrast, the township-level cadres in this dataset have a mean age of only 41 years old, far from the “glass ceiling” of promotion to a higher level.Footnote 44

Interestingly, CCP membership is not a statistically significant predictor for promotion at the local level. Extant research finds that non-CCP members have a lower chance of moving to top cadre ranks and are thus underrepresented in leadership positions at the provincial and municipal levels. The result implies that non-CCP members are at least equally likely to be promoted locally than CCP members. Figure 4 shows that the conditioned effect of a combination of Party school training and CCP membership on promotion is even slightly stronger among non-CCP members trained by Party schools than the trained CCP members. Considering Lee's finding that a CCP member is 32 per cent more likely to undergo Party school training than a non-CCP member, the implication of this study's result is striking. Even if CCP members are much more likely to be selected for Party school training, the effect of training on their probability of promotion tends to be weaker than for non-CCP members.Footnote 45

Figure 4: Conditional Effect of Party School Training and CCP Membership on Promotion

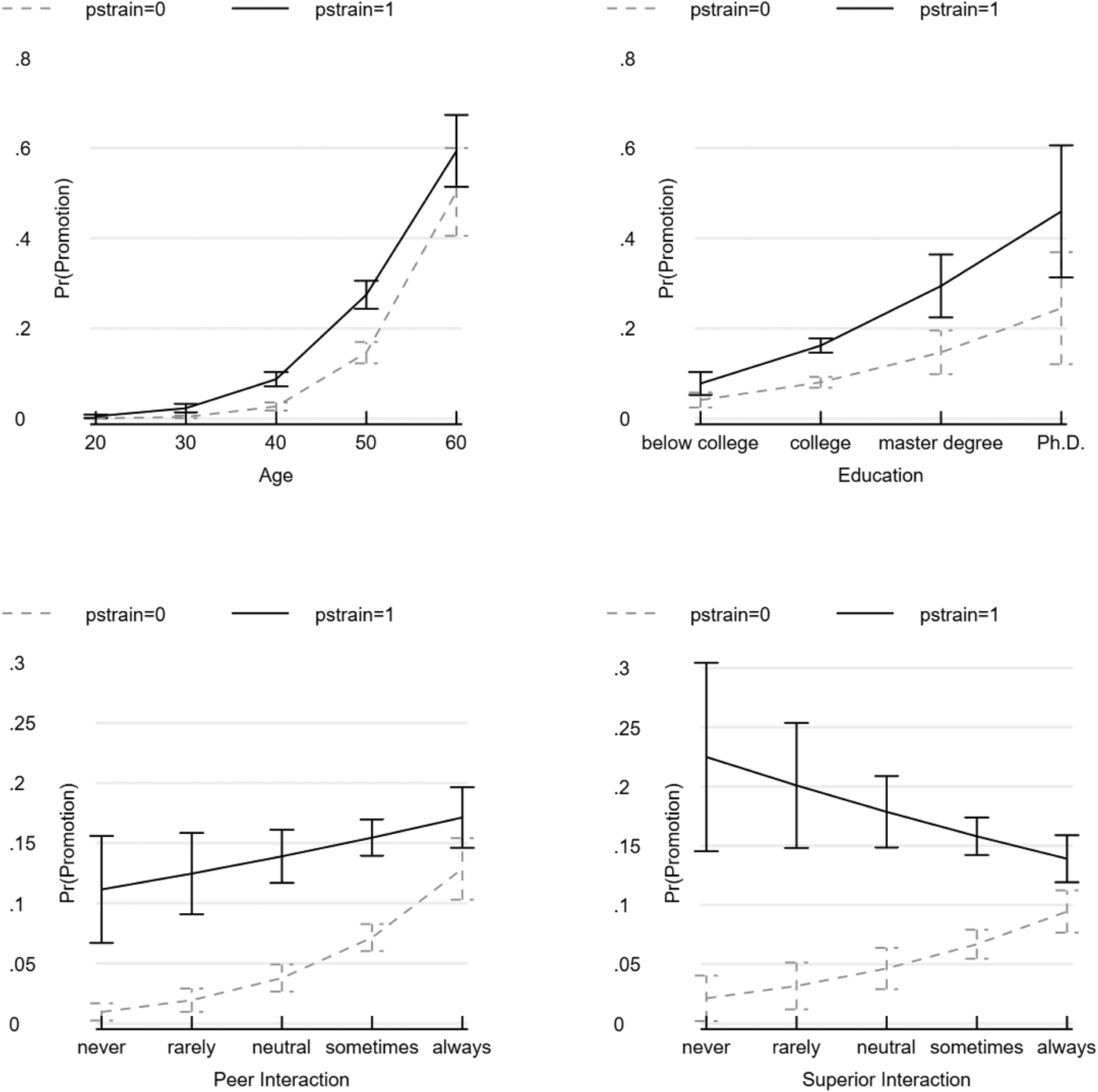

Township-level cadres’ interaction with their peers has a significant and positive impact on the probability of their promotion to the county level. This finding provides empirical evidence to Thomas Heberer and Gunter Schubert's proposition that township-level cadres are mutually dependent and must collaborate strategically to improve individual performance and their workplace's overall performance to be considered for promotion.Footnote 46 The implication is that fierce competition for promotion may not be the only dynamic of cadre interaction between different levels of the Chinese administrative hierarchy. Competition for promotion may become more intense the higher the administrative rank. At the local level, however, cooperation may be as important as competition for cadre promotion. On the other hand, as the bottom-left panel of Figure 5 shows, Party school training has a positive effect when peer interaction is at its maximum. Even when the interaction between the two variables indicates that when compared to no training, Party school training's positive impact on promotion weakens as peer interaction increases (Table 4).

Figure 5: Conditional Effect of Party School Training on the Predicted Probability of Cadre Promotion

On the other hand, interaction with leaders from a higher administrative level does not significantly contribute to cadres’ promotion to county-level positions. This result aligns with Pierre Landry, Xiaobo Lü and Haiyan Duan's finding that individual connections with superiors matter for political selection at the elite level but not at the lower administrative level.Footnote 47 It indicates that the “strong Party organization that ensures cadre control and discipline” – instead of personal connections with individual superiors – may be a more salient influence on local cadres’ chances of promotion.Footnote 48 In this study, the Party school training's conditional effect on promotion becomes weaker as local cadres interact more with superiors, as shown in the lower-right graph in Figure 5. Note that trained cadres still enjoy a higher probability of being promoted than untrained ones; however, a combination of Party school training and more frequent superior interactions affects promotion negatively.

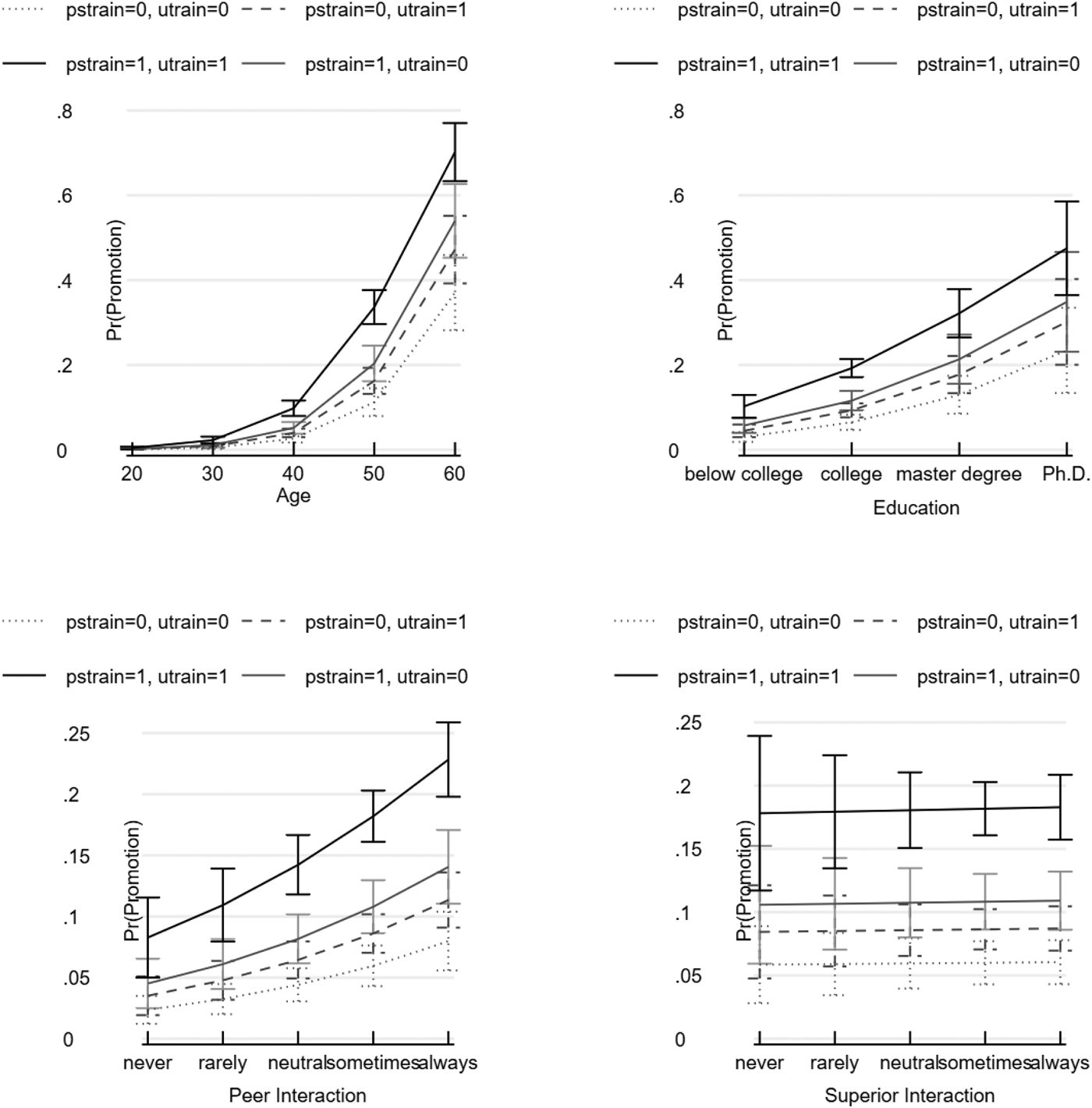

The findings so far suggest that Party school and university training positively affect the probability of promotion to varying degrees. Would a cumulative experience of both training types further boost local cadres’ likelihood of getting a promotion? Figure 6 illustrates the combined impact of various types of training on local cadre promotion conditioned on different factors. The results clearly indicate that those who have both Party school and university training experience enjoy the highest chance of being promoted, even when conditioned by age, education level and interactions with peers and superiors. The content of the training offered by Party schools and academic institutions implies that cadres who received both types of training are likely to be both loyal to the Party organization and more competent. A combination of loyalty and a higher level of competence makes this group the most competitive among local Chinese cadres. Unsurprisingly, individuals who receive neither training are the least likely to be promoted. This finding indicates that it is hard for cadres to advance their careers from the lower end of the Chinese administrative hierarchy without allegiance and a reasonable level of competence.

Figure 6: Conditional Effect of Cadre Training on the Predicted Probability of Cadre Promotion

Interestingly, as shown in Figure 6, among cadres who received either type of training, those trained by Party schools only have a slightly higher probability of being promoted than those trained by universities. That this difference is not more considerable suggests that the more substantial impact of Party school training on promotion found in the above analysis may only manifest itself in a hypothetical context where the leader faces the problem of either promoting a loyal agent or a competent agent. In such circumstances, loyalty could overweigh expertise, probably because a disloyal agent may cause more damage to the regime than an incompetent one. In practice, where leaders need to balance agent allegiance and competence and choose from a pool of potential candidates with various training records, it seems that Party school training does not grant a distinct advantage over university training for individual cadres.

Another interesting pattern that can be found from a comparison of Figure 5 and Figure 6 is that when conditioned by interactions with superiors, the probability of promotion for cadres who have both types of training does not decrease as the interaction frequency increases among all patterns of training combinations. On the contrary, when conditioned by the effect of superior interactions, Party school training alone leads to a decreased probability of promotion as the frequency of interactions with higher-level leaders increases. This finding helps to explain why personalist patronage ties tend not to contribute to promotion at the lower administration levels.Footnote 49 Even if local cadres can establish connections with higher-level leaders and boost their loyalty rating with Party school training, their probability of promotion will likely decrease without an adequate level of competence. The improved level of competence gained from university training mitigates the negative effect of patronage ties on local cadre promotion. This mitigation effect provides evidence that loyalty and competence at the township level play an important role during the promotion process. In the meantime, a combination of personalist patronage and allegiance to the Party may be conducive to promotion only when local cadres also have a high degree of competence.

Robustness

I conducted several modified analyses to check the empirical findings’ robustness to ensure that the statistical results remain robust. My approaches included analysing the logistic regression models using only CEM-matched or PSM-matched data, specifying alternative coarsening patterns to set a different maximum level of imbalance in the dataset, and using logit instead of the default probit method to estimate the propensity score during the PSM stage. The results were robust to these checks.

Conclusion

This article contributes to our understanding of cadre promotion mechanisms at the lower level of the Chinese administration by exploring the causal relationship between loyalty, competence and local cadre promotion. While research on promotion at higher levels of the Chinese government abounds, rarely any quantitative evidence has been presented for below the county level. Using an original dataset of local cadres’ training records and a rigorous data-processing method, I examine the impact of loyalty and competence on township-level cadres’ promotion. The results broadly support the hypothesis that loyalty and a higher degree of competence increase the probability of promotion for township cadres. On the other hand, personalist connections do not contribute to the likelihood of promotion at this administrative level and may even decrease a lower-level cadre's chances if the cadre does not possess a certain level of competence.

The findings are conducive to a nuanced understanding of the mechanisms behind authoritarian regime resilience. The promotion mechanism revealed in this study represents the regime's balancing efforts to deliver performance and maintain political control at the local level. By cultivating local cadres who are more familiar with and more likely to be supportive of Party policy doctrines through the Party school apparatus, the party-state aims to maintain political authority and dominance in China's complex bureaucratic system. However, only when accompanied by competence can allegiance to the Party contribute to a local cadre's career advancement.Footnote 50 Such an emphasis on loyalty and competence indicates that even at a level that seemingly has a mere indirect impact on state elites, the regime is still trying to keep its feet on the ground.

This study suggests that the perennial debates about “red” versus “expert” are still relevant, at least at the local level and for the period covered by the data in this study.Footnote 51 Being “expert” seems to matter more for cadre promotion under the administrations of early reform-period leaders than the revived focus on “redness” under President Xi's administration. It would be interesting to disaggregate cadre training data by different administrative periods and test whether training effects vary over generations of leadership. Unfortunately, such information is unavailable in this study. Future research should pay special attention to the characteristics of training under the different generations of leadership. The subtle distinction between “redness” and “loyalty” also warrants further exploration. While existing literature on promotion tends to operationalize “loyalty” as personal patronage ties, this study points to cadres’ loyalty to the Party institution and thus speaks more to the “redness” as a desirable characteristic.

One potential caveat of this study is that township cadres’ time until promotion is unavailable owing to limited data availability. In the strictest sense, the results in this paper provide limited support for the selective institutionalization mechanism since they present the causal impact of regime patronage on local cadre promotion in general rather than on cadres’ fast-track promotion. It is worth noting that Pang, Keng and Zhong use a somewhat arbitrary measure to distinguish between regular-track and fast-track promotion, which is also not without limitations.Footnote 52 For example, recent research finds that higher competence is correlated with a shorter time until promotion for prefecture and county leaders, which contradicts cadre performance's impact on term length in Pang, Keng and Zhong's study.Footnote 53 Future research could explore a less arbitrary definition of the dual-track promotion system and the impact of loyalty and competence on such a system.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Rongbin Han, Shane P. Singh, Markus M.L. Crepaz, Mollie J. Cohen, Abraham D. Sofaer and three anonymous reviewers for valuable advice on earlier drafts of this article.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Biographical note

Linan JIA is a PhD candidate in the department of international affairs at the University of Georgia, United States. Her research focuses on comparative institutions, political behaviour, public opinion and media politics.