In the context of China's rapid economic growth and rising role in the first two decades of the 21st century, the question of where its academia is moving to becomes a matter of concern on a global scale. Embedded in literature on academic (de)colonization and intellectual pluralism, research was conducted on the status quo of educational studies on and in mainland China within the world knowledge system. We report its findings in order to respond to continuing struggles within the contemporary mainland Chinese academic society in social sciences, especially educational studies, and between global “centres” and “peripheries.” As Tierney argues, it seems that “China has reached submission parity with the U.S.” in terms of the number of academic publications in social sciences, and although “data for sub-disciplines [such as educational studies] were not available, one might speculate that they follow a similar trend.”Footnote 1 However, there seems to be a lack of inquiry into their quality and scholarly contribution on a global stage. From theoretical perspectives of the world system (of knowledge production) and higher education internationalization, the project collects and analyses relevant academic publications and reflections from both distinguished overseas ethnic Chinese and non-Chinese education researchers for answering the major question: what is the global “status” of educational research on mainland Chinese issues and studies conducted by mainland Chinese education researchers, and how do we describe and interpret it?Footnote 2

Along with the contemporary large-scale and fragmented process of globalization, many incongruous facets of human existence have been forced together into a giant tumbler, while non-Western intellectual traditions of those excluded and epistemologically disenfranchised gain attention, acquire agency and demand a new synthesis.Footnote 3 Indeed, the findings of the research project reveal the status quo and potential for interactions/dialogues between academic communities with diversified traditions, and such interactions and dialogues may contribute to the entire global community of educational studies.

Knowledge and Theoretical Background

The research project has been conducted based on the following theoretical perspectives related to the internationalization of higher education, China's role in world knowledge production, as well as tensions between internationalization/globalization and local pre-existing knowledge. Burawoy argues about the global knowledge asymmetries that “the Northerners are […] quite oblivious to the specificity of social problems in the South and they, therefore, see their framework as universal.”Footnote 4 For scholars in the Global South, they are de facto encouraged to address “problems intelligible in the North” and “conform to the paradigms operative in Northern countries,” in order to publish in established Northern journals cited by Northern scholars.Footnote 5 It seems obvious that “more social sciences of the South are drawn into the orbit of Northern journals, Northern research funds, Northern debates – and Southern powers tend to incentivize such participation – the more they may be drawn away from the issues most relevant to their local or national context.”Footnote 6 Such a loop reinforces the inequality of the world knowledge systems.

As Woldegiorgis argues, “debate on decolonisation in higher education should not be tied to the experience of colonization [… since] the global North […] has violently delegitimised and repressed other knowledge systems with or without colonial experience.”Footnote 7 In terms of East Asia, as Marginson argues, its higher education and research “have been shaped by [its] locational cultural and political elements, and closely affected by the Western imperial intervention and more contemporary models.”Footnote 8 In terms of China, although without a history of being fully colonized, Yang, Xie and Wen hold that historically China's modern education system has been based almost exclusively on Western learning, from textbooks and teaching contents through to the organization and operation of the institutions.Footnote 9 Such imported “Western learning” includes higher education models that originated from Western societies and disciplinary knowledge produced by Western academic communities. The term “Western” in these narratives can be understood largely as Anglo-American and Western European especially Anglophone, or imperialist. As a “semi-peripheral” country identified by Wallerstein, China has its ambition of “advancing […] toward the core.”Footnote 10 There is a tension between its ambition and the reality, particularly in social sciences.

The contemporary connotation of higher education internationalization can be tentatively defined as the process of integrating an international and intercultural dimension into the teaching, research and service functions of the institution,Footnote 11 which mainly contains the exchange of people, ideas, and goods and services between two or more nations and cultural identities.Footnote 12 Beyond quantifiable indicators such as the number of people moving across borders, Wu and Zha propose a typology to identify the interactions between domestic and foreign higher education and knowledge systems based on directions and tendencies (i.e. inward- and outward-oriented) of the diffusion of innovations, such as knowledge, culture, higher education models and norms.Footnote 13 The inward and outward diffusion of innovations during higher education internationalization can be categorized into two types, “expansion diffusion” driven by the attractiveness of innovations and “relocation diffusion” driven by the material process of internationalization including the mobility of people and programmes.Footnote 14

Over the past three decades, higher education internationalization in China has transformed from mainly inward-oriented to a more balanced approach, and its growing presence in the world knowledge system has been of increasing concern to researchers.Footnote 15 Borrowing from the rhetoric of the centre–periphery model and world systems theory, China's higher education and academic system was once seen as a “gigantic periphery” with limited original knowledge contributions.Footnote 16 Presently, China has been regarded more as an active and ambitious player in higher education internationalization, both in promoting world university rankings and in terms of the participation of student and scholar mobility. In terms of educational research in China, together with research in other social sciences, it has reached “parity” with the English-speaking world in the quantity of academic publications, while its performance is less stellar in terms of more qualitatively oriented indices focusing upon influences, as shown by the acceptance rates of submissions and the citation of its scholarship.Footnote 17 The academic knowledge exchange between China and the Anglophone academic community is still largely unilateral, reflecting the asymmetries in the global knowledge system.

As Ding and Zhou argue, researchers in China need to move beyond the binary oppositional thinking mode of cosmopolitanism versus nationalism, tradition versus modern, or China versus foreign/West.Footnote 18 However, as Yang, Xie and Wen argue, in the process of integrating into the world knowledge system, it is still difficult for Chinese and Western value systems to achieve good compatibility with each other.Footnote 19 In terms of educational studies on and in China, the tensions between internationalization/globalization and indigenization/localization have become increasingly apparent. To be more specific, for instance, since English dominates as the major world academic language, especially for those non-English-speaking latecomers, promoting “internationalization” and integrating into “globalization” means using English for academic publication and international collaboration. Since language involves the dominance of ideas, this affects the form and substance of methodologies, approaches to science and scholarly publication.Footnote 20 Indeed, the power of English affects the role of local languages and cultures in the Global South.Footnote 21

In the last decade, China's internationalization of knowledge production has generated a shift of research patterns and methods in the field of educational studies. Meanwhile, although potentially China's present efforts to indigenize its social sciences research can make important contributions to a rebalancing of imported and local patterns of knowledge,Footnote 22 the tension between internationalization/globalization and local pre-existing knowledge (e.g. local or traditional languages, philosophies, cultures, research paradigms, methods and topics) seems to be long-lasting: it appears that the marginalization of “peripheral” educational research within the world knowledge system is systemic because the key index enlisted to measure and compare the knowledge production excludes non-English publications.Footnote 23 This phenomenon has a significant impact on academic knowledge production in non-Western countries, especially for those in the humanities and social sciences (educational studies included) which are by their nature locally oriented, preferring to focus on local community issues.Footnote 24

Research Design and Methods

To respond to such existing issues and problems, the project was conducted by a group of education researchers from different institutions in mainland China and Hong Kong,Footnote 25 while its outcomes include, for instance, a theoretical reflection on the status quo,Footnote 26 quantitative and qualitative analyses of the quality of relevant publications in international academic journals,Footnote 27 and analyses among reflections from both distinguished overseas ethnic Chinese and non-Chinese education researchers towards relevant issues.Footnote 28 Bibliographic and content analyses on Social Science Citation Index (SSCI) journal articles in English as well as semi-structured interviews were conducted during a three-year period. In terms of bibliographic and content analyses, a major data set of SSCI journal articles related to China and educational studies has been created, which contains several sub-data sets including articles authored by education researchers from different geographical regions (e.g. mainland China, Hong Kong, Taiwan and non-Greater China countries/regions).Footnote 29 In terms of field research, semi-structured interviews were conducted with nine distinguished overseas ethnic Chinese and eight distinguished non-Chinese education researchers. These overseas interviewees were based in countries/regions such as the US, UK, Canada, Australia, Singapore and Hong Kong. Interview questions mainly related to the present situation of educational studies on and in mainland China, the positioning of mainland China's education researchers and their academic outcomes within the world knowledge system, the significance of educational studies on and in mainland China in the future, as well as the relationship between internationalization of educational research in China and local knowledge (e.g. local or traditional research paradigms, methods and topics).Footnote 30

Findings

Through bibliographic and content analyses of SSCI journal articles and qualitative analysis of semi-structured interview data, the findings reveal the rapidly increasing but still relatively limited influence of educational studies on and in China in the world knowledge system. The “centre's habitual disregard and ignorance of ‘peripheries’” issues and research outcomes, as described by Burawoy,Footnote 31 also exist in China, together with tensions between internationalization imperative and the need for protecting traditional knowledge and culture. As mentioned by one of the overseas non-Chinese interviewees, “internationalization has objectively formed a ‘two-track system’ in Chinese universities” in the past decade, recruiting “star professors” to publish SSCI journal articles and making other faculty members primarily responsible for teaching and teacher training.Footnote 32 For both educational research in mainland China and research on China's educational issues as a field, the superficial prosperity has always been accompanied by deep challenges.

Growing but limited global presence

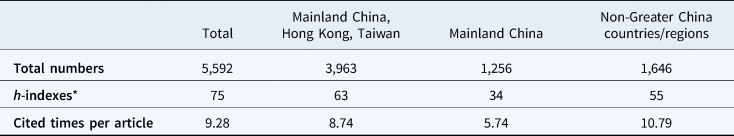

According to a bibliographic analysis of SSCI journal articles on education in China (2000–2018) authored by researchers from mainland China, Hong Kong, Taiwan and other non-Greater China countries/regions, the findings reveal that the number of papers published by mainland Chinese scholars has grown significantly while the academic influence has been relatively limited. It shows that during the targeted time period, about 5,592 SSCI journal articles on China's education issues were published, including 1,256 papers authored by educational researchers from mainland China (see Table 1). The number of papers as well as the number of times they are cited are on the increase year by year. In terms of the top 150 highly cited papers authored by mainland Chinese scholars (as an individual author or one of the co-authors), a high proportion of these were co-authored by researchers from different regions/countries (i.e. mainland China, Hong Kong, Macau, Taiwan and other countries). According to a content analysis, among the top ten highly cited papers authored by mainland China's researchers, both the research paradigm and topics of these studies conform to the international mainstream, and diversified empirical research methods have been used, which are different from the traditional philosophical speculation-based method of educational research in China. Importantly, most of the Chinese authors have overseas study and/or research experience.

Table 1. Numbers of Target SSCI Journal Articles by Authors’ Countries/Regions (2000–2018)

Meanwhile, the bibliographic analysis shows that the target SSCI journal articles authored by mainland Chinese researchers are relatively less influential (see Table 2). Most of the influential (highly cited) papers related to China's educational issues around the world were authored by researchers from Hong Kong, Taiwan and other countries/regions. Among the top 150 highly cited papers, their first authors are mainly from Taiwan (29.25%), the US (22.45%), Hong Kong (21.09%), Australia (7.48%) and Canada (5.44%). Compared to mainland China, Hong Kong and Taiwan may still be considered as “centres” of knowledge production for research on Chinese education on a global scale.Footnote 33 Moreover, in terms of the top ten highly cited papers published by mainland China's scholars, they have largely failed to contribute to the existing theoretical system based on China's own epistemological/intellectual tradition.Footnote 34

Table 2. Numbers, Average Cited Times, and h-Indexes of Target SSCI Journal Articles by Authors’ Regions

* The h-index is the maximum value of h that the given set of articles has at least h number of papers that have each been cited at least h times.

Findings from the analysis of the interview data also show the increasing but limited global impact of educational studies on and in mainland China. According to the reflections from distinguished overseas non-Chinese education researchers, the overall visibility of research conducted by China's domestic education researchers has increased during the past two decades, but its international influence is still limited. China's domestic academic community has been identified as “on the borderline between ‘centres’ and ‘peripheries’” of the world knowledge system.Footnote 35 One of the participants stated that mainland Chinese researchers “have made great contributions, but it is difficult for non-Chinese speakers to understand their research outcomes.”Footnote 36 In terms of the reasons for the status quo, according to their reflections, although the overall quality of English journal articles authored by Chinese researchers has improved, there is still a considerable proportion of papers that are of poor quality. For instance, one of the participants mentioned that “a considerable number of papers can hardly be regarded as academic research [… while] some of the authors just give an overview of a research field and propose some broad discussions [without rigorous evidence].”Footnote 37 Moreover, some interviewees pointed out that the language barrier limits effective communication between Chinese scholars and journal editors and reviewers. This, to a great extent, limits the improvement of the quality of their papers and internationalization/modernization of their research paradigms. Such circumstances clearly constrain the outward “expansion diffusion” of China's original innovation, as identified by Wu and Zha.Footnote 38

In terms of another group of participants, most distinguished overseas ethnic Chinese education researchers feel that the international influence of research on Chinese education has continued to increase over the past two decades, especially in three aspects: China-related topics at international conferences, the increase in the number of papers published in international journals, and the emphasis on Chinese scholars in overseas universities.Footnote 39 Some ethnic Chinese interviewees pointed out that such an increase in visibility or influence is not only due to the relative improvement in the quality of research outcomes produced by China's domestic academic community but also due in large part to its rapid economic growth and the excellent exam performance of its basic education system, such as the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) exam. For instance, one of the participants mentioned: “When I was doing research in Japan in the 1990s, [… Japanese scholars] did not care about China, and it was the same in Europe and the US at that time.”Footnote 40 He further argued that “nowadays, China's higher education is attracting more international attention, and this is [also] because of China's economic and social development.”Footnote 41 Considering the scale and quality of China's education system, its domestic educational research outcomes (and practices) have been underestimated by the Anglophone academic community due to factors such as language barriers.

Tensions between “centres” and “peripheries,” internationalization and local knowledge

First, the findings reveal that “centres’” habitual disregard of “peripheries” still exists in the world knowledge system in terms of educational studies. Distinguished scholars from the Global North, such as Ruth Hayhoe, Lynn Paine, Paul Bailey, Stanley Rosen, Heidi Ross, John Hawkins, Stig Thøgersen, Anthony Welch, Simon Marginson, Motohisa Kaneko and Yutaka Otsuka, have long focused on mainland China's education issues.Footnote 42 Meanwhile, as previously mentioned, SSCI journal articles on Chinese education grew rapidly in the first two decades of the 21st century. However, interview data reveal that “centre” academic communities’ habitual disregard of “peripheries” still exists. The data collected from overseas non-Chinese participants show that generally speaking, except for well-known scholars such as Ruth Hayhoe, Philip Altbach and Simon Marginson who were frequently mentioned by interviewees, most non-Chinese education researchers in major English-speaking countries have limited interest in China's educational issues. Moreover, several participants pointed out that education research itself is a very “local” discipline, and such a disciplinary characteristic determines that a large proportion of scholars only focus on local issues.

For instance, one of the participants mentioned that many American education researchers focus only on issues in their local states or even local districts, rather than global or even national issues. According to reflections from distinguished overseas ethnic Chinese scholars, visiting scholar programmes and programmes for attracting overseas returnees have promoted the inward-oriented “relocation diffusion” of innovations identified by Wu and Zha, which, as previously mentioned, refers to the learning of foreign knowledge, culture, higher education models and research paradigms through the material process of internationalization such as the mobility of people.Footnote 43 Meanwhile, interviewees also emphasized the fact that research methods training drives (non-material process based) inward-oriented “expansion diffusion” of innovations in the field of educational studies in mainland China, driven by the attractiveness of foreign knowledge and research paradigms.Footnote 44

Second, the findings reveal the tension between the internationalization process and China's pre-existing local knowledge. According to reflections from overseas non-Chinese scholars “China's academic system, culture, and writing style are very different from those of major English-speaking countries,”Footnote 45 which limits the outward diffusion of its knowledge and innovations. The ethnic Chinese interviewees reflected that mainland China's education researchers need to conform to international mainstream paradigms in selecting research topics, writing literature reviews, implementing empirical methods and citing existing foreign/Western theories in order to dialogue with the international academic community. They believe that there is a gap between China's domestic/indigenized educational research and internationalized studies on Chinese education issues, and therefore there is only limited effective dialogue between the domestic and overseas/Anglophone academic communities.

Ethnic Chinese interviewees also pointed out that dialogue with the international academic community is the basis and prerequisite for constructing and further developing China's own knowledge system. Moreover, overseas non-Chinese participants have reflected on the negative impact of China's institutional-level incentive policies towards academic knowledge production. One of them mentioned that “if China's local education researchers devote all their energy to publish[ing] SSCI journal articles due to incentive policies and promotion mechanisms, [the] importance of local [Chinese] academic journals and their focus on local education issues will be reduce[d].”Footnote 46 A mechanism that encourages publication in English SSCI journals may lead to tensions between overseas returnees and other scholars within the academic community.

Suggestions for enhancing China's contribution to global educational knowledge

According to the research findings, distinguished overseas ethnic Chinese and non-Chinese education researchers suggest optimizing the present situation from four major aspects. First, the participants all believe that Chinese universities and its local academic community should encourage young overseas returnees to play a more active role to further promote the internationalization of China's educational research, especially in terms of research paradigms and methods. One of the non-Chinese participants pointed out that “young returnees in mainland China's top research universities are under enormous pressure to publish SSCI journal articles.”Footnote 47 “However, publishing SSCI journal articles does not help them to enhance their reputation[s] in the domestic academic community, while only publishing in Chinese may not help fast promotion, and which puts them in a dilemma.”Footnote 48 Therefore, young overseas returnees in the field of educational studies need dual support from both university administrators and the local academic community. One ethnic Chinese interviewee pointed out that “although returnees are well-trained in research methods, have good foreign language [English] capacity and may have the effect [of promoting internationalization], most of what I have seen is indeed [that] such effect is gradually disappearing.”Footnote 49 He further remarked that “they [young overseas returnees] are driven or seduced by different forces, including administrative ones, and everyone is so busy that they have little energy to focus on their own research. Therefore, although there are many young returnees in our field [of educational studies], few have really grown into influential scholars [in mainland China].”Footnote 50

Second, according to the interview data, overseas non-Chinese interviewees believe that it is necessary for Chinese universities to optimize their academic evaluation systems, regard SSCI journal publications from a rational perspective and encourage young scholars to conduct academically in-depth research. One of the participants stated that “whether it is a journal article or a book chapter, the key [of the assessment] is to examine its substantial academic contribution.”Footnote 51 In terms of reflections from ethnic Chinese interviewees, one of them commented that for young returnees who have received rigorous academic training, “[Chinese universities] should provide them with a good living and working condition[s], allowing them to calm down and do research, while many young scholars spend a lot of time doing administrative work, or write a lot of urgent and policy-oriented reports [for the government and institutions] which are completely different from academic research, and some returnees have been fully ‘converged’ by [the atmosphere of] the local community, which I think is a pity.”Footnote 52

Third, the research findings also include participants’ suggestions that the mainland Chinese academic community should establish and improve new platforms, such as English journals, for introducing research outcomes in the field of educational studies to the world. Finally, they mentioned that Chinese scholars should work with their global counterparts to enhance the world presence of educational studies, since the visibility of educational studies on and in mainland China depends to a considerable extent on the worldwide importance of educational research in a broad sense. Moreover, both ethnic Chinese and non-Chinese participants believe that an improvement in the use of empirical research methods would continue to contribute to the influence and importance enhancement for both educational studies on/in China and the entire discipline.

Conclusion

The major findings of the project reveal the increasing but relatively limited impact of educational studies on and in China in the world knowledge system. Having experienced a rapid internationalization process since the turn of the century, China's domestic academic community in the field of educational research seems to be still on the borderline between “centres” and “peripheries.” Meanwhile, except for those distinguished scholars mentioned by the interviewees, a large proportion of non-Chinese education researchers in the West still have limited interest in China's educational issues.Footnote 53 “The exclusion of even the mention of Chinese educational research from Western [English] journals seems problematic in this age of globalization, given China's size and changing role.”Footnote 54 However, although “there is a tendency to presume or expect that Chinese scholars will align their work with Western research endeavours and theoretic frames,” it is not vice versa for Western, especially Anglophone, scholars.Footnote 55 To a certain extent, the research project has proved the habitual disregard of “centres” towards educational issues and research outcomes in/from “peripheral” countries/systems. Such unequal relationships between “centres” and “peripheries” in the world knowledge system have caused tensions between internationalization and local knowledge/culture, although the feature of educational research that prefers to focus on local issues may also be a major reason for “central” academic communities’ lack of interest in practices in “peripheries.” Such tensions have prevented Chinese scholars from outwardly diffusing innovations (i.e. contributing to the global academic community).

At present, it seems necessary for China's domestic academic community to promote the internationalization of research paradigms and methods, further support young overseas returnees and encourage the conduct of research with theoretical depth in order to achieve substantive dialogue with the international academic community and enhance the global presence of educational studies, as well as social sciences in general, on and in China. This can be regarded as the basis and precondition for the further development of China's own knowledge and make it contribute to the existing knowledge and theoretical system on a global scale. As Yang argues, “featured by uncertainty, [the contemporary trend of] globalization is also an opportune moment to develop new and different intellectual and academic discourses,” as well as promote interactions/dialogues between them.Footnote 56 As previously mentioned, such interactions and dialogues may contribute to the entire worldwide community of educational studies. This is also the reason for our critical use of the term “status” (diwei 地位), even though it is widely used in academic narratives and policy documents in Chinese contexts when discussing the situation of research on and in China in the global context.

Competing interests

None.

Hantian WU is a professor in the College of Education at Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China. His research interests include comparative and international higher education, higher education internationalization, higher education development in emerging economies and academic knowledge production in a global context.

Rui YANG is a professor and dean in the Faculty of Education at the University of Hong Kong. With a track record on research at the interface of Chinese and Western traditions in education, his research interests include education policy sociology, comparative and cross-cultural studies in education, international higher education, educational development in Chinese societies and international politics in educational research.

Mei LI is a professor in the Institute of Higher Education, Faculty of Education at East China Normal University, Shanghai, China. She specializes in internationalization of higher education, comparative and international higher education, and higher education policy in China.