In 2014, the National People's Congress of China promulgated the revised Budget Law, which profoundly changed the fiscal activities of local governments.Footnote 1 The revised law stipulated that “Provinces, autonomous regions, and cities directly under the central government permitted by the State Council can issue local government bonds (difang zhengfu zhaiquan 地方政府债券, LGBs hereafter) to finance infrastructure construction.” For the first time since the first Budget Law in 1994, local governments were allowed by the central government to issue bonds.Footnote 2 Shortly afterwards, the State Council issued its “Suggestions on improving the management of local government debt” as a more detailed instruction for local governments.Footnote 3 The policy proposed a “combination of unblocking and blocking” (shudu jiehe 疏堵结合), as LGBs were promoted as a new way for local governments to borrow from the financial market, while the ways previously used, which violated central regulations, represented by certain financial activities of local government financing platforms (LGFPs), would be prohibited.Footnote 4 LGBs become the major part of local government debt in China. By the end of February 2022, LGBs accounted for 99.46 per cent of local government debt according to the Ministry of Finance (MOF) (Table 1).

Table 1: Ratios of LGBs to Local Government Debt from 2017 to February 2022

Source: MOF, http://yss.mof.gov.cn/zhuantilanmu/dfzgl/sjtj/index.htm. Accessed 25 May 2023.

LGBs bring profound change to local debt shaped by decentralized central–local relations.Footnote 5 How LGFPs operated was largely determined by local governments, but LGB policies are made by the central government for local governments to implement. Local governments at different levels have to apply to the MOF for their annual bond quotas for specific projects. The MOF calculates quotas mainly according to the fiscal capacity of local governments and the financing demand of projects. Provincial governments issue and repay bonds for themselves and on behalf of municipal and county-level governments under their jurisdiction; they then transfer the capital to provincial projects and lower-level governments after bond issuance.

This article examines how LGBs operate and how they expand our understanding of the political economy of local debt in China. It analyses the development and operation of LGBs and makes the following contributions. First, LGBs reveal the newest structure of local debt. Local debt boomed following the launch of a 4 trillion-yuan stimulus package by the State Council in 2008.Footnote 6 Local governments established LGFPs to boost infrastructure investments, and these platforms borrowed heavily from the market through financial derivatives. Although the literature has noted that LGFPs led to a surge in local debt in the early 2010s,Footnote 7 very few studies examine how LGBs have changed local debt since 2015. Second, this article examines the changing role of the central government in local debt and generates theoretical implications for the political economy of local debt in terms of central–local relations and fiscal federalism.Footnote 8 The role of the central government receives scant attention in this regard because it was less involved in the development of LGFPs. However, the the LGB quota system is indicative of central government intervention and control over local debt. The authority and autonomy of local governments in local fiscal activities have been restricted since the introduction of LGBs, reflecting a centralized trend in central–local relations and a new mode of fiscal federalism. The policies on LGBs also reveal the changing central government objectives through different periods. Third, the article raises policy implications by reiterating the local debt problem. Since the mid-2010s, the central government has used infrastructure investment supported by LGBs as a major tool to maintain economic growth. Bond quotas and issuance have experienced rapid growth and the ratio of debt to fiscal capacity at the local level has increased to an alarming level. Without dealing appropriately with the imbalance between local income and expenditure, local debt will continue to rise.Footnote 9

The current study draws on policy document analysis, statistical descriptions of LGB data and semi-structured interviews with local government officials. Documents come from the websites of governments at different levels. The LGB data are collected from the Finance Yearbooks of China, the disclosed reports on LGB issuance on the website of China Central Depository and Clearing, and the CELMA platform established by the MOF. The CELMA platform provides information on the values of LGBs issued by 31 provinces and five city governments with independent planning status (jihua danlie shi 计划单列市) since 2015.Footnote 10 We conducted semi-structured interviews with five municipal government officials of the financial departments in two cities, Lianyungang 连云港市 in Jiangsu province and Chengde 承德市 in Hebei province. Three interviewees were staff members familiar with LGBs, and two were heads of the local debt offices in Lianyungang and Chengde. We did not have access to officials in the central government, but interviewees offered their views on the roles and considerations of the upper-level policymakers. Of the two cities, Lianyungang has the more developed economy, and the interviewees were able to provide different viewpoints according to the differences in economic development, thereby drawing a more comprehensive picture of LGBs. The next section describes how local debt in China accumulated before LGBs and reviews the literature. The third and fourth sections examine the development and operation of bonds, highlighting the roles and considerations of the central government throughout different periods. The financial risks of LGBs are then discussed, followed by the conclusion.

The Political Economy of Local Debt in China

The development of local debt before LGBs

Adam Liu, Jean Oi and Yi Zhang together provide a comprehensive analysis of local debt in China before the advent of LGBs.Footnote 11 Local governments accumulated a certain amount of debt in the 1990s through state grain enterprise losses, borrowing loans and buying treasury bonds. The level of debt, however, remained low, as the amount of debt was small and also because the central government had established asset management corporations to tackle non-performing loans.Footnote 12 Entering the 2000s, “unfunded mandates” placed local governments under huge expenditure pressures as the central government set targets and launched projects in infrastructure construction, education, rural development and other sectors, which had to be paid for by local governments.Footnote 13 Meanwhile, the tax reform in 1994 significantly reduced the tax revenues of local governments as a large proportion of local tax income was diverted to the central government.Footnote 14 Although there were tax rebates and fiscal transfers from the central government, local governments did not have enough budgetary income to manage expenditure tasks.

Local governments thus turned to the “extra-budgetary” income that did not have to be shared with the central government.Footnote 15 Land transfer income became the most important way of funding infrastructure projects and boosting public finance.Footnote 16 This income kept local debt at a relatively low level. However, the situation radically changed when a 4 trillion-yuan stimulus package was launched in October 2008 in a bid to counter the global financial crisis. Local governments were required to invest up to 2.2 trillion yuan in different sectors by the end of 2010. Land transfer could not generate sufficient money within such a short time and so local governments turned to LGFPs, which are local state-owned companies that fund and construct infrastructure projects and operate in the public sector.Footnote 17

LGFPs dragged local governments into accumulating local debt. LGFPs raise money from the financial market through many channels: bank loans, issuing corporate bonds (Chengtou 城投 bonds)Footnote 18 and using other financial derivatives such as trust products, finance leases, structured notes, and so on. Most of these financing methods have terms of less than five years. Local governments also helped LGFPs to boost their credibility. First, land was injected into the companies as physical collateral. Because land belongs to the state, it was a nominal asset of LGFPs that the companies had the right to develop.Footnote 19 LGFPs calculated the future income that could be derived from the land after its development and used this value to collateralize. Second, local governments issued guarantees on behalf of LGFPs to pay investors with fiscal revenue if the companies could not pay the debt.Footnote 20 The guarantees were issued in secret because they violated the central regulation on restricting local debt.Footnote 21 The guarantees were the main reason that LGFPs were able to keep leveraging market capital; however, they also blurred the boundary between the LGFPs’ debts and local government debt. The amount of LGFP debt guaranteed by local governments, which was the major part of the “implicit local debt,” reached alarming levels when compared with local government income in the early 2010s.Footnote 22 Yet the exact amount remained unknown. This implicit debt posed a huge risk to local financial systems owing to its vast amount, lack of transparency and uncertainty. The fact that LGFP debt could hardly be separated from local government debt is the reason why most studies use the term “local debt,” instead of “local government debt,” to analyse the debt situation in China.

Anticipating the negative effects of LGFPs on local debt, the MOF designed LGBs in early 2009 as a way to fund infrastructure projects. Initially, the MOF experimented with LGBs in small amounts of bond quotas and pilot areas for five years, allowing local governments to continue using LGFPs. The central government admitted that LGFPs were the most suitable choice to achieve the stimulus target.Footnote 23 Although some regulations regarding LGFPs were enacted by the MOF and the State Council, they did not emphasize regulation enforcement. In 2015, after the global financial crisis had eased, the problem of implicit local debt became urgent. As the experiment with LGBs had progressed well, the bonds were promoted across the country to replace LGFPs as the major financing source for infrastructure construction.

The evolution of central–local relations

Since the economic reform launched in 1978, the term decentralization has been widely used to describe central—local relations in China.Footnote 24 In the 1980s, authority for fiscal income and expenditure was devolved to local governments through the fiscal contracting system.Footnote 25 After the tax reform of 1994, authority over fiscal income was largely centralized, but expenditure responsibility remained decentralized. The widening gap between income and expenditure drove local governments to look to land transfer income and then LGFPs for finance. As the central government could hardly (and chose not to) intervene in the “extra-budgetary” income generated by LGFPs, the authority over fiscal income was decentralized again in the early 2010s. Scholars of public finance and local debt studies in China thus concluded that the most recent form of central–local relations has been decentralization.Footnote 26 But LGBs challenge this conclusion and lead to our first theoretical implication. The central government extensively intervenes in local debt through bond quotas. It is the central government that decides on the bond issuing amount and the selection of infrastructure projects, reflecting a new wave of centralization and mirroring the political centralization of the late 2010s after Chairman Xi Jinping 习近平 assumed office.Footnote 27 Although recent studies have discussed how the recentralization under the Xi administration may affect local debt, they focus on the effects of political campaigns, such as the anti-corruption campaign, but they surprisingly leave out the change in the local debt structure brought by LGBs.Footnote 28

Discussion of central–local relations extends the understanding of fiscal federalism in the Chinese context. Fiscal federalism is believed to properly describe the fiscal governance and central–local relations in China, but there is no scholarly consensus on its specific form. Some scholars advocate the concept of market-preserving federalism, which means that local governments have authority over the local economy and promote market development.Footnote 29 However, there are mismatches between the concept and China's situation, such as a central government that makes unilateral decisions to change the regime, a bank system that leads to soft budget constraints and lower economic efficiency owing to the lower level of fiscal democracy, and local tax competition.Footnote 30 Studies focusing on land finance or LGFPs, although scrutinizing different aspects, agree on fiscal decentralization. LGBs, therefore, bring new perspectives for fiscal federalism in China. After the 2008 global financial crisis, fiscal federalism across different countries revealed a centralized trend, as the central/federal government intervened more to boost local economic development.Footnote 31 China is no exception and engages in a specific form of centralization as demonstrated by LGBs. Examining the development and operation of LGBs helps to shed light on the most recent form of “fiscal federalism, Chinese style.”Footnote 32

The policy implication is that fiscal centralization through LGBs does not solve the key problems in local debt, such as “unfunded mandates.” Local governments still have to rely on debt-financing tools for infrastructure projects.Footnote 33 The LGB quota system only slows down local debt growth. The ongoing expenditure pressure has been pushing local debt to alarming levels in many places across the country, and the Chinese government must urgently address the widening gap between local fiscal income and expenditure.

The Development and Operation of LGBs

This section reviews the development and operation of LGBs at different stages divided by “critical junctures.”Footnote 34 At each juncture, LGBs adapted their mode of operation, bringing profound changes to local debt. The review illuminates the changing roles and considerations of the central government and reflects on how LGBs affect the political economy of local debt.

2009–2014

2009–2011: MOF issues and repays bonds for provinces

In February 2009, the MOF launched its policy on “Budget management of local government bonds in 2009,” marking the birth of LGBs.Footnote 35 LGBs were designed as a new financing source for infrastructure projects with unique operation modes. From 2009 to 2011, only 31 provincial and five city governments with independent planning status could issue LGBs, but the MOF issued and repaid bonds on their behalf. With the consent of the National People's Congress, the MOF set an annual nationwide quota of 200 billion yuan and allotted specific quotas for each province. Provincial governments selected appropriate projects and then submitted applications with the project information and the LGB amounts required to the MOF for approval. If the project was approved, the MOF then issued bonds and transferred money downwards. The investors and underwriters of LGBs were mostly state-owned commercial banks.Footnote 36 LGB interest rates ranged from 85 per cent to 115 per cent of treasury bond rates, with the same maturity period issued one to five days before the LGB issuance, which were significantly lower than Chengtou bonds and other financial products. The income generated through LGBs was tax-free. The bond maturity was from three to seven years. Money raised through LGBs went to the projects that had applied. Provincial governments sent repayments to the MOF, which then repaid investors. Repayments came from fiscal revenue. The central and provincial governments’ strong credit meant that there was no other collateral needed for LGBs.

Why did the central government design LGBs in such a way? As the deputy secretary of MOF explained in 2009, LGBs were issued to provide matching funds to centrally led investment projects.Footnote 37 The central government would undertake large-scale infrastructure projects across the country, but these projects would not rely solely on central-government funding: local governments would have to provide matching funds. Because of limited yields and the fact that local governments experienced fiscal shortages, these projects attracted very little market investment. As the LGB issuer, the MOF used its credibility to help local governments raise market capital as matching funds. The low interest rates of LGBs also reduced the cost of financing compared to borrowing through LGFPs. The MOF set several criteria for project selection, and providing matching funds to centrally led projects was the top priority.Footnote 38 These projects tended to be located in the least developed western region as local governments there had less fiscal income and lacked access to the financial market.Footnote 39 The MOF thus allocated more bonds to these regions (Figure 1).

Figure 1: LGB Issuance in Economic Regions, 2009–2014

Source: Finance Yearbooks of China, 2010–2015.

2011–2014: pilot schemes for local governments issuing and repaying bonds

In October 2011, the MOF selected Shanghai, Zhejiang, Guangdong and Shenzhen to take part in a pilot in which local governments had the authority and independence to issue LGBs themselves after the allocation of quotas, with the MOF still being responsible for the repayments.Footnote 40 Jiangsu and Shandong were added to the pilot areas in June 2013. In May 2014, the MOF then delegated the authority for bond repayment to the pilot areas. The six pilot areas, plus Beijing, Jiangxi, Ningxia and Qingdao, were permitted to issue and repay LGBs on their own. Meanwhile, the MOF increased the nationwide quota to 400 billion yuan in 2014. The MOF asked the governments of the pilot areas to hire financial intermediaries to conduct a credit rating of all LGBs based on local fiscal capacity and debt situations. From 2009 to 2014, the bonds were tightly controlled by the MOF, with only limited decentralization in pilot areas. They were therefore labelled “quasi-treasury bonds.”Footnote 41

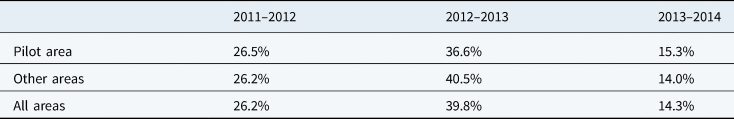

The aim behind the pilot schemes was to promote LGBs to local governments within a short period. Figure 2 shows the average annual amount issued by every province at this stage. The difference in bond quotas between most places was less than two billion yuan, which was only enough to fund a few small-sized projects and was a very small amount compared with the expenditure. By allocating similar amounts of LGBs across the country, the central government aimed to make every provincial government familiar with the bonds. Delegating authority for issuing and repaying bonds to local governments in the pilot areas also contributed to this intention. The MOF issued and repaid the bonds because it was experienced in issuing treasury bonds and could help local governments to quickly adapt to LGBs.Footnote 42 As understanding of the LGBs grew, local governments gradually took over certain responsibilities and decision making. The first four pilot areas were key economic development hotspots, where the governments had considerable fiscal resources and experience of the market. It was easier for these governments to adapt to the new mode of operation and pass on their experience to others. The last four pilot areas included places in the less-developed regions. The issuing amounts of LGBs in the pilot areas increased more quickly than those in other areas (Table 2). These circumstances indicated that the MOF was ready to grant the autonomy to issue and repay LGBs to governments across the country. According to one interviewee in Chengde:

Those pilot provinces set an example for us. No one knew how to issue government bonds before. They also gave us confidence. For example, Zhejiang and Jiangsu [rich provinces] set a certain range of interest rates and bond prices, which were based on their economy. But those in Jiangxi [a less-developed region] had similar statistics. Then we [in less-developed Hebei] could also set similarly low interest rates to save the financing cost without being worried about scaring away investors.Footnote 43

Figure 2: Average Annual Issue of LGBs by Province, 2009–2014

Source: Finance Yearbooks of China, 2010–2015.

Table 2: Annual Growth Rate in LGB Issuance, 2011–2014

Source: Finance Yearbooks of China, 2012–2015.

Despite this limited decentralization, the MOF still maintained control over the approval of projects and the allocation of bond quotas.

Since 2015

The diversified categories of bonds

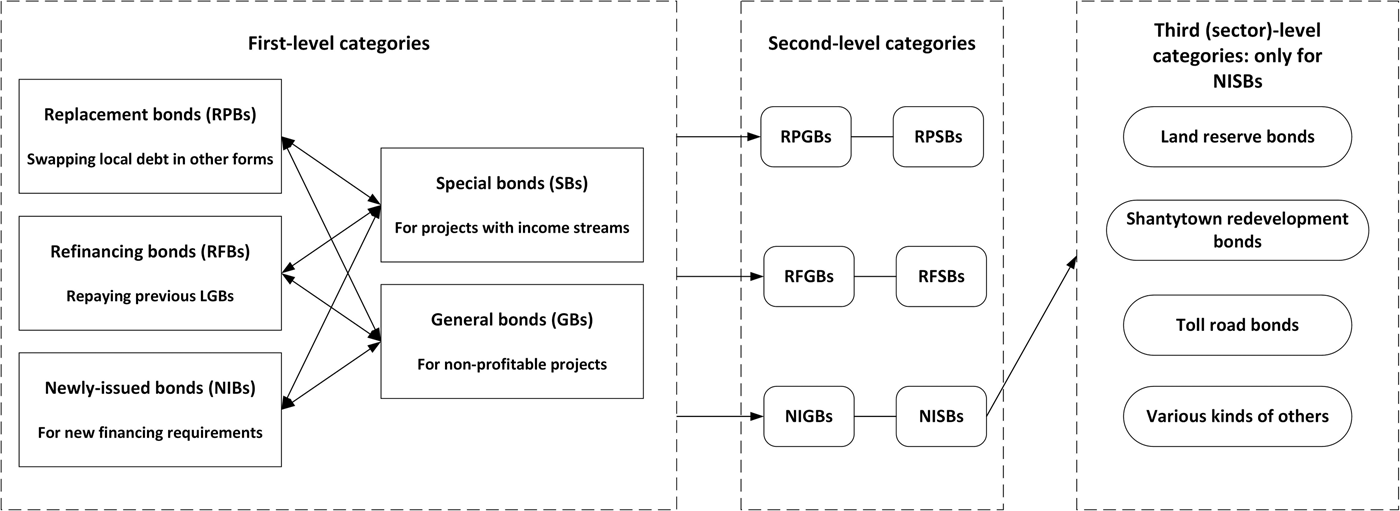

The revised Budget Law endorsed LGBs as the main financing source for infrastructure projects across the country. The MOF and the State Council have modified the LGBs' mode of operation so that they may be better applied by local governments. LGBs are divided into newly defined categories at different levels (Figure 3). There are two sets of taxonomies at the first level. On the one hand, LGBs consist of general bonds and special bonds. General bonds are for welfare projects without revenue streams, which local governments repay with fiscal revenue. Special bonds are for projects with yields, and repayment comes from project income or the corresponding government fund. This taxonomy is important to the bond operation. The State Council defined local general debt and local special debt as new categories of local debt in 2015.Footnote 44 Local general debt is generated only by issuing general bonds, and local special debt only comes from special bonds. The correspondence between the categories of local debt and those of LGBs is the foundation to prevent implicit local debt from rising again.

Figure 3: Categories of LGBs

Source: Compiled by authors.

Notes: Abbreviations for different categories are used owing to space limitations.

On the other hand, LGBs are also divided into newly issued bonds, replacement bonds and refinancing bonds. Newly issued bonds emerged in 2015 and are for new financing requirements for new or ongoing infrastructure projects. Newly issued bonds have become the most important part of LGBs, and account for the largest proportion of bond issuance since 2018, because they are used to fund ever-expanding infrastructure construction (Figure 4). The policies set out by the central government regarding the quota system and guidance on project selection are mostly aimed at newly issued bonds.

Figure 4: Issue of Newly Issued Bonds, Replacement Bonds and Refinancing Bonds, 2015–2021

Source: The CELMA platform.

Replacement bonds were launched in 2015 as a special tool to deal with the implicit local debt. The State Council required local governments to calculate the cumulative debt (including implicit debt) they were responsible for repaying before the end of 2014. Then, local governments exchanged the debts with replacement bonds of an equal amount. The period for swapping the debts lasted from 2015 to 2018, and replacement bonds stopped being issued after 2019. Replacement bonds played a key role in quickly reducing the financial risk generated by LGFPs. Mostly relying on short-term financial products, LGFPs – and the local governments behind them – experienced huge repayment pressures in the early 2010s. Lacking sufficient funds, they had to borrow more to repay the debt, leading to a fragile financial structure and high levels of risk. Issuing replacement bonds gave local governments several more years to repay, significantly reduced repayment pressures and helped to stabilize the local financial situation. According to one interviewee involved with the issuing of replacement bonds in Lianyungang:

We surely welcomed replacement bonds. We experienced a severe fiscal shortage and were faced with a large amount of repayment. Those bonds helped us to save a lot of money. As for how to repay them, well, it was not something that should be considered at that moment.Footnote 45

Refinancing bonds, which were introduced in 2018, repay earlier LGBs that reach their maturity dates. Refinancing is common among different bond products. It is worth noting that since 2019, refinancing bonds have been authorized by the MOF for swapping the implicit local debt accumulated after 2015 (this implicit debt is discussed below), although this function is still being trialled in some areas. Once replacement bonds were no longer being issued, risk was reduced through refinancing bonds being swapped for the implicit local debt.

The two parallel taxonomies in the first level combine to produce the second-level category. Every kind of LGB at this level corresponds to a specific function. For example, newly issued special bonds are for new financing requirements for new or ongoing profitable infrastructure projects. In 2017, the State Council promoted “project-level income-financing balanced special bonds” as the major part of newly-issued special bonds.Footnote 46 Projects using these bonds should prove that project income is sufficient to repay the bonds’ principal and interest to investors. The third-level category includes projects funded by project-level income-financing balanced special bonds in different sectors. As an example, the MOF introduced land reserve bonds, toll road bonds and shantytown redevelopment bonds and explained how these bonds should be applied to fund projects. By following the examples, local governments have come up with bonds for dozens of other sectors, including rural revitalization, high-speed railways, higher education, and the like.

The formula used by MOF in calculating quotas

The annual nationwide quotas significantly increased from billions to trillions to match the real demand from infrastructure projects. The MOF has added more principles to the calculation of quotas.Footnote 47 The demands of LGBs cannot result in excessive debt. The MOF evaluates local fiscal capacity and debt situations to develop bond quotas that ensure local governments can pay off the debt. A project's qualities are thoroughly examined. In order to be approved, a project is assessed on whether it contributes to the public good and development, has adequate preparation work, is of reasonable investment scale, generates enough profits to repay the bonds, starts as planned and attracts extra market investment. In 2017, the MOF disclosed its formula for calculating the quota of newly issued bonds for a specific local government:

The variables and coefficients are explained in Table 3. Some of the coefficients and variables are explained with specific formulas, while some are only given general instructions on calculation. “Crucial projects” (zhongda xiangmu 重大项目) include centrally led projects and local projects in the “crucial sectors” (zhongda lingyu 重大领域) emphasized by the State Council, such as new infrastructure, new energy, rural revitalization, and so on. The list of the sectors changes annually or on important occasions to match the national development strategies at that time. The performance management of local government debt means there is a system designed by the MOF to evaluate local governments on how they manage their debt. How the system works has not been disclosed. In summary, the MOF focuses on local fiscal capacity, debt situations and the quality of projects in terms of their contributions to national policy objectives.

Table 3: Coefficients and Variables Used to Calculate Quotas of Newly Issued Bonds

Source: “Caizhenbu fawen guifan xinzeng difang zhengfu zhaiwu xian'e fenpei guanli” (The MOF issued guidance on allocation and management of new local government debt quotas). Gov.cn, 1 April 2017, http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2017-04/01/content_5182868.htm. Accessed 25 May 2023.

The hierarchical application and approval procedure for quotas

Local governments still need to apply for their quotas from the MOF, but the procedure becomes more complex and involves more government levels at the local scale. Based on the application materials, the quotas are almost independently decided by the central departments. Applications mainly provide information on projects and local governments. Project information should cover the project's contributions to national policy objectives, public benefit and local development; the demand for LGBs; the income structure (only for projects using special bonds); and the schedule for repayment and construction. Local governments should also hire independent financial intermediaries to provide financial and legal opinions on the projects. Local government information should include data on local financial situations such as fiscal revenue, debt situations, market development and local development plans.

The procedure for applying for LGB quotas is shown in Figure 5. It is based on the local administrative hierarchy. Lower-level applications are decided by the next level up and the central government. The county-level financial department collects the application materials from other departments for the next year and submits them to its municipal counterpart.Footnote 48 The municipal financial department examines county-level projects and rejects unqualified applications. It then passes the municipal and county-level materials to the provincial financial department, which submits the provincial, municipal and county-level applications to the MOF to apply for the provincial quota. The MOF examines applications and then sends those selected to the State Council, which in turn does the same and sends on the applications to the National People's Congress. The National People's Congress, as the highest authority in China, does the final review and sets a nationwide quota and the quotas for every province. In most cases, the State Council and the National People's Congress do not alter the decisions made by the MOF, as they trust in the MOF's financial expertise. The quotas are issued to every provincial financial department through the MOF. Examinations within the central departments are strict, and the final quotas are usually smaller than the amount local governments apply for. For example, a province in the western region was only granted 40 per cent of the amount it applied for in 2021.Footnote 49 Within the quota, the provincial people's congress approves the provincial projects and the quotas for municipal units. The provincial financial department issues the LGBs and transfers money to the provincial projects and municipal units. Municipal and county-level people's congresses and financial departments follow a similar procedure for approving quotas and transferring money.

Figure 5: Application and Approval Procedure for LGB Quotas

Source: Compiled by authors.

LGBs as a Tool of the Central Government to Achieve Policy Objectives

Risk reduction and control

In different periods since 2009, the central government has played different roles with distinct intentions to create a sustainable structure of local debt progressively. The “strategic goal of economic development” is the central government's top policy priority.Footnote 50 A stable local financial system with sustainable debt is key to maintaining development and thus is heavily emphasized. Therefore, following the five-year experiment with small quotas and pilot areas to promote the use of LGBs across the country, the central government's priority was risk reduction and control. A staff member in Chengde argued:

LGBs, to a large extent, “sort” local debt. We in the financial department did not know how much debt other departments owed. They did not need to report to us. They probably did not know it clearly either. It was a mess (hutuzhang 糊涂账). But with LGBs, we consider how much we should borrow and know exactly how much we should repay.Footnote 51

Implicit local debt was chaotic by the end of 2014. The payment guarantees issued by local governments were only acknowledged by the few participants in the deal. This opaque and informal structure encouraged over-borrowing and jeopardized financial stability. Thus, the central government promoted the use of LGBs to make local governments officially liable for every debt they owed. Meanwhile, replacement bonds were used to swap the cumulative implicit local debt before 2015. An intense three-year swapping period successfully converted the implicit local debt, worth more than 10 trillion yuan, into LGBs. Since late 2014, LGFPs have had to operate as independent companies, and any guarantees made by local governments that help LGFPs raise money have been strictly prohibited.Footnote 52 By swapping the implicit local debt and detaching LGFPs from local governments, the central government tried to “open front doors and close back doors” (kaiqianmen duhoumen 开前门,堵后门) or “combine blocking and unblocking” to normalize local debt and reduce risk. Moreover, replacement bonds extended repayment deadlines and effectively mitigated risk from 2015 to 2018, while refinancing bonds continue to control risk by swapping the newly accumulated implicit local debt after 2015.

The formula used by MOF to calculate quotas also highlights risk control. The variables fiscal, performance and the coefficients x 3 and x 4 not only focus on local fiscal capacity and debt levels but also on how well the local government deals with debt. The hierarchical application and approval procedure reveals the similar determination of the central government to control risk. Local governments attach much importance to investment but care less about debt. Some local leaders believe that the soft budget constraints still exist and that the upper-level governments will bail them out in a worst-case scenario.Footnote 53 Many leaders simply think that, thanks to their short tenures (five to ten years), debt repayment will fall on to their successor's shoulders and so they borrow as much as possible in the meantime to boost investment. Such thinking was reflected in the implicit local debt generated by the LGFPs. Supervision and assessment by the upper-level governments (and the people's congress at the same level) in the application and approval procedure prevent local governments from excessive borrowing and consequently curb risk. The head of the local debt office in Chengde shared her opinion:

The departments now need to prepare many materials for applications. We will look at them first, although we hardly reject any. But we will bring questions and make suggestions to make them more financially efficient. Then the upper-level (financial) department will assess again and reject some. That is how they control the risk. It is not up to the departments (at this level) anymore.Footnote 54

Narrowing economic inequalities

LGBs are also used to attract more investment to the least developed western region and thus reduce regional economic inequalities.Footnote 55 A challenge for the central government when issuing LGBs is how to convince the financial market to invest in places and sectors which generate less profit. Driven by shareholder value and risk aversion principles, investors tend to focus on the more profitable opportunities.Footnote 56 The central government uses general bonds to resolve this issue. The MOF has been allocating more newly issued general bonds to the western region (Figure 6). These bonds require no project yields and are repaid from fiscal income. Infrastructure projects with very limited revenue streams, such as rural roads with cement pavements completed in richer regions, are still under construction or about to start in the west. Newly issued general bonds are suitable for these projects. Although local governments need to use fiscal income to repay investors, the long maturity terms of these bonds (more than ten years) and the low interest rates reduce the pressure. The credibility of provincial governments also boosts investors’ confidence in securing long-term stable revenue. It is worth noting that the amount of newly issued general bonds in the west was less than that in the east in 2015 and 2016. According to a staff member in Lianyungang, replacement general bonds were issued in larger amounts in the west and accounted for a large share of the quotas in those two years, as “most of the projects in those less urbanized areas could only be swapped with general bonds because they generated no revenue at all.”Footnote 57

Figure 6: Issuance of Newly Issued General Bonds in the Economic Regions, 2015–2021

Source: The CELMA platform.

Guidance on project selection

The central government also tries to influence project selection through policy guidance to support national policy objectives. As mentioned above, the MOF and the State Council have been setting out policies that determine the “crucial sectors” in which capital raised from LGBs should be invested. The head of the local debt office in Lianyungang offered his opinion on the “crucial sectors”:

With the “crucial sectors,” we know better how to select projects. We can streamline our investments and use our advantages to help with national policy priorities. For example, Lianyungang is a port city on the route of the Belt and Road initiative. We have invested heavily in infrastructure projects in logistics, transportation and other related sectors to make the city a bridgehead (qiaotoubao 桥头堡) and a pivot of the initiative.Footnote 58

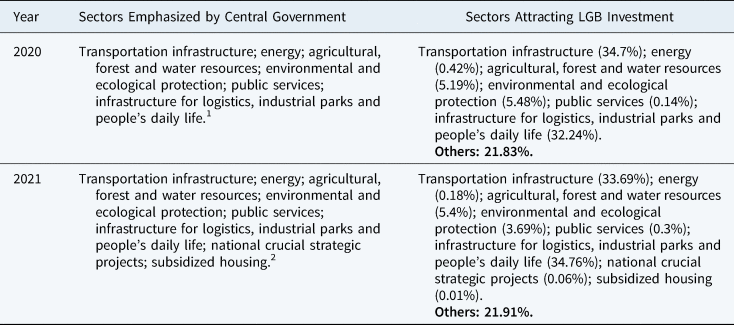

In this way, the central government uses policies on “crucial sectors” to make LGB investments align with national development strategies. It seems that this goal has been achieved. Table 4 compares the sectors emphasized by the central government and the sectors that attract investments through newly issued special bonds. Nearly 80 per cent of the bond capital was invested in the sectors favoured by the central government in 2020 and 2021.

Table 4: Sectors Emphasized by the Central Government and Sectors Attracting LGB Investment

Source: 1Data taken from “Guanyu zhuanxiangzhai caizhengbu huifu toulu liuda fangxiang” (The MOF suggests six sectors that special bonds should invest in). 163.com, 30 October 2020, https://www.163.com/dy/article/FQ56AUDI05158BFB.html. Accessed 25 May 2023. 2 Data taken from “Difang zhengfu zhuanxiang zhaiquan shi luoshi jiji caizheng zhengce de zhongyao zhuashou” (Special bonds are an important starting point for implementing a proactive fiscal policy). CCTV.com, 12 April 2022, http://news.cctv.com/2022/04/12/ARTIMMvUHyh3NlZZfJkZhpFB220412.shtml. Accessed 25 May 2023. Sectors attracting LGB investment in 2020 and 2021 are calculated according to reports on the MOF website, http://kjhx.mof.gov.cn/yjbg/. Accessed 25 May 2023.

The Risks of LGBs

Although the central government tries to minimize the risk, the issuing of LGBs still leaves local governments with a large amount of debt. For local governments, the ratio of debt to fiscal capacity in 2015 was 89.2 per cent.Footnote 59 The ratio increased to 93.6 per cent in 2020.Footnote 60 By the end of 2021, the MOF announced that the balance of local government debt was 30.47 trillion yuan. Although no official data have been released, the fiscal capacity of local governments was believed by some research institutions to be less than 30 trillion yuan, making the ratio exceed 100 per centFootnote 61 – 100 per cent is the threshold set by the MOF for the local debt risk alert.Footnote 62 Furthermore, this ratio does not consider implicit local debt. Except for LGBs, local governments still rely on public–private partnerships formed through LGFPs, government buying services and government-guided funds to finance infrastructure projects.Footnote 63 These financing modes lead to implicit local debt – for example, when some local governments still secretly issue payment guarantees on behalf of the LGFPs.Footnote 64 The International Monetary Fund calculated implicit local debt to be 30.8 trillion yuan in 2018 – even after the replacement bonds swap – and was projected to be 57.8 trillion yuan in 2022.Footnote 65 According to these data, the amount of debt that local governments need to pay off may be three times their fiscal capacity by the end of 2022.

The surge in LGB issuance and the never-ending implicit local debt are rooted in the developmentalism promoted by the Chinese government and the fiscal regime that leads to decreased local fiscal income. China's top policy priority has been economic growth since the 1980s. “Stabilizing growth” (wenzengzhang 稳增长) to achieve the annual national GDP growth target set in the government work report every year is repeatedly emphasized by the central government on important occasions. Since the 2010s, the government has been using different market instruments to achieve development objectives through promoting infrastructure investment and urbanization when other sectors, like consumption and exports, experience slow growth owing to changing domestic and international contexts.Footnote 66 LGBs have been one of the most important market instruments. According to a staff member in Chengde, “In most cases, the quota significantly increases if there is much pressure on boosting economic growth.”Footnote 67 Matching the debt level with fiscal capacity is indeed among the top priorities when calculating bond quotas, but the MOF also pushes the debt ratio towards the danger threshold to maintain growth. Local governments also try to increase the quotas indirectly. In an interview, the head of the local debt office in Chengde shared that “departments usually deliberately propose more projects to apply for LGBs (changkoubao 敞口报) so that when some applications are rejected, they may still meet the investment target.”Footnote 68 Moreover, the quota system means that the amount of LGBs issued far from meets the level of demand needed to maintain growth. Once again, local governments have to rely on ways to generate more implicit local debt. Swapping the new implicit local debt by refinancing bonds reduces the uncertainty of local debt but cannot reduce the level of debt. The financial risk generated by excessive local debt cannot in reality be alleviated without reforming the fiscal regime.

Conclusion

The development and operation of LGBs reveal the different strategies used by the central government during different periods to reform and create a sustainable structure of local debt. LGBs reveal a centralized trend in central–local relations by demonstrating a very active and interventionist central government that designs every step of bond deployment for specific purposes. Centralization through the bonds is more extensive than during the 1994 tax reform. At that time, the central government took a large proportion of local fiscal income but hardly intervened in how local governments created more income or spent money. Nonetheless, LGBs ensure that the MOF not only has the final say over the amount of bonds issued and the selection of projects but also affects how local governments choose projects through its policy guidance. Liu, Oi and Zhang use the term “kicking the can down the road” to describe how the central government deals with local expenditure.Footnote 69 LGBs challenge this view by showing the close involvement of the central government in local fiscal activities. This finding also reminds us that every round of centralization is unique and embedded in a specific historical context.

Is there still fiscal federalism in China after the introduction of LGBs? The answer may be yes, as local governments still hold a certain degree of authority over fiscal activities (selecting specific projects in line with national policy discourse and having more space to decide on other financing methods such as public–private partnerships through LGFPs). However, LGBs alter the consensus on fiscal decentralization. Since the 2010s, there has been a centralizing trend in global fiscal federalism.Footnote 70 Central governments/banks worldwide have been involved more extensively in the local economy through either fiscal transfer or credit provision to maintain growth, including in the US and Canada. Those two countries previously promoted “fend for yourself” federalism in which the federal government rarely intervened in the fiscal activities of subnational governments.Footnote 71 The Chinese government has followed this trend with LGBs. The fiscal federalism mode in which LGBs operate resembles the “cooperative” and “coercive” federalism exemplified by Australia (also the US) whereby the central and local governments cooperate (applying for and approving quotas), but the central government uses its superior position to coerce the lower-level government into implementing the centre's policy objectives (risk control and reduction, helping with less-developed regions and supporting “crucial sectors,” which may not be prioritized by local governments), suggesting centralization.Footnote 72 LGBs add empirical flesh to the varieties of fiscal federalism. A valuable research agenda is to be found in exploring in detail how LGBs expand the understanding of fiscal federalism in China and beyond.

To what extent can LGBs solve the problem of local debt in China? It is not looking promising. Before LGBs, scholars believed that the solution to local debt accumulation was profound institutional reform to change fiscal income and expenditure assignment between central and local governments.Footnote 73 But instead the central government attempts to “circumvent rather than tackle difficult institutional reform, opting for an easier fix to avoid the potentially high political costs.”Footnote 74 There has been no reform since the implementation of LGBs. The central government neither allocates more fiscal income to local governments nor takes on more spending tasks. It tries to help with “unfunded mandates” by using the credit of the provincial government to raise funds for the lower-level governments, but the money still comes from the market, and local debt continues to grow. It is not necessary to wipe out local debt as long as it exists in a financially secure and efficient form. The quota system of LGBs contributes to this goal, but the pressure on maintaining economic growth forces the MOF to push debt to alarming levels. The quota system also motivates local governments to find other financing sources for projects, and as a result, implicit local debt rises again.

Echoing the appeals of existing studies, this article contends that the central and local governments should work together to narrow the gap between local fiscal income and expenditure. Local debt can only be sustainable when the central government takes on more expenditure tasks or transfers more funding downwards, or when local governments find a way to increase income.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the two anonymous referees and the editorial manager Raphaël Jacquet for very helpful comments on the earlier draft of the article. The article was supported by the European Research Council (ERC) Advanced Grant “ChinaUrban” (Grant No. 832845) and the China Scholarship Council.

Competing interests

None.

Fulong WU is Bartlett Professor of Planning at University College London. His research interests include urban development in China and its social and sustainable challenges. His latest book, Creating Chinese Urbanism: Urban Revolution and Governance Change (UCL Press), reveals the profound impacts of marketization on Chinese society and the consequential governance changes at the grassroots level. He is currently working on a European Research Council Advanced Grant on China's urban governance.

Fangzhu ZHANG is an associate professor at University College London. Her main research interests focus on innovation and governance, urban village redevelopment and migrant integration, as well as eco-innovation and eco-city development in China. She is currently working on a European Research Council Advanced Grant on China's urban governance.

Zhenfa LI is a PhD candidate at University College London. His research interests include urban governance, financialization and economic geography, currently with local government bonds in China as the empirical focus.