Published online by Cambridge University Press: 11 February 2009

In Ox. Pap. xxxii (1967) i ff., no. 2617, Mr. Lobel published fragments which he shows reason to believe are from Stesichorus’ Geryoneis. Further work has been done on them by Professor D. L. Page and Mr. W. S. Barrett, and the more substantial fragments are included in an Appendix to Page's Lyrica Graeca Selecta (Oxford, 1968). Fr. 4, the most considerable piece, describes how, in Lobel's words: ‘a person, who I do not think there is much room to doubt is Heracles, delivers a secret attack on somebody which consists in shooting him through the head. Though only one “forehead”, one “crown”, and one “neck” are mentioned and the Geryones of Stesichorus had six hands and six feet (Page, MG fr. 186; Stesichorus, fr. 9; LGS fr. 56) and therefore presumably three heads, as elsewhere (e.g. Hes. Theog. 287), the possibility that Geryones is here in question does not seem to be ruled out.’

1 A draft of this paper was given to the Oxford Philological Society. It was also read by Mr. W. S. Barrett, and the present version owes a great deal to his comments, and to information he has given me on improvements made to the papyrus-text by himself and by Professor Page, who has also very kindly read the draft.

2 65. 7–20. 7; Johansen, VS 94, 144 and pl. 24, 2. This certainly represents the subject and is certainly much the oldest surviving representation. The very crude style makes exact dating difficult, but shape and decoration alike point to a date around the middle of the seventh century. See further below.

3 Brock, in Dunbabin, , Perachora ii 262, no. 2542, pls. 106, 110. See further below.Google Scholar

4 Kunze, Arch. Schildbänder (01. Forsch. ii. 1950, to6 ff., pls. 30, 50–2, 63, 65). See further below.

5 Paus. 5. 19. 1. On the Throne of Apollo at Amyclae Herakles was shown driving the oxen (ibid. 3. 18. 13). Herakles and the cattle are shown also on a few Attic black-figure vases: see Brommer, Vasenlisten 2 51, and Beazley, ABV 376, Leagros Group no. 234 (column-hater Bologna 5i, from Bologna, Zannoni, pls. 76, 9 and 23–4), and 377, no. 245 (oenochoe Boulogne, 476, Pfuhl, fig. 282). See also below, p. 219, with n. 11.

6 F. de D. iv. 4. 141–57, pls. 66–73; Poulsen, Delphi, 171–4, figs. 67–9. The scene occupied the six metopes of the west end, all very ill preserved: 1, Herakles (feet only surviving) and the hound; 2, Geryon (see below, p. 209 n. 4); 3–6, cattle.

7 0l. iii. 170 ff., figs. 201–4, pl. 40, 9; Buschor and Hamann, pls. 91 f.; Ashmole, Yalouris, and Frantz, Olympia 27, figs. 180–5. See also p. 209 n. 4 and p. 211 n. 3.

1 Sauer, Sog. Thes. 176 ff., pl. v. See also p. 209 n. 4.

2 Below, p. 210 n. 1, p. 213 nn. 6–8, p. 214 nn. 1, 4, 5. More than 60 examples are known. Some of them are collected and illustrated by Clement, P. A., Hesp. xxiv (1955) 1 ff.Google Scholar, pls. 1–5. Brommer, Vasenlisten 2 (1960), lists two Corinthian, two Chalcidian, five Attic red-figure, and sixty-four Attic black-figure. The Corinthian are mentioned above, p. 207 nn. 2 and 3, the Chalcidian discussed below, as are two of the red-figure. The third is Beazley, ARV 2 163, Paseas (the Cerberus Painter) no. lo, a fragmentary cup in the Villa Giulia and Heidelberg; see Beazley, Camp. Fr., pl. 1, 8–9, etc., where he also mentions the other two (both fragmentary cups): Athens, National Museum, Acropolis frr. 46 (Langlotz, pl. 3) and 123. All are of the late sixth century. See also p. 211 n. 2, and p. 214 n. 8. The subject then disappears from the Athenian repertoire, but is found occasionally in fourth-century South Italian vase-painting, a Hellenistic relief-bowl (Hausmann, pl. 67, r) and Roman sarcophagi. See below, p. 209 n. 4.

3 The place of origin of these vases is not established. Some of them carry inscriptions in the Chalcidian alphabet, and Rumpf in his great monograph Chalkidische Vasen (1927) came down (40 ff.) in favour of Chalcis in Euboea, though recognizing the arguments for a Western colony (chiefly the lack of finds from mainland and Eastern Greece: against this the quality, much superior to that of any painted pottery certainly produced in the West). H. R. W. Smith in The Origin of Chalcidian Ware (1932) argued for production by Greeks in Etruria, probably at Caere (Argylla); and R. M. Cook, GPP (1960), 159, admits the Etruscan claim as the strongest. The case for a South Italian colony, perhaps Rhegion, has been argued again by Vallet, Rhegion et Zancle (1958), 212 ff., 225 ff., 301. L. H. Jeffery, Local Scripts (1961), 81 and elsewhere, provisionally accepts Euboean Chalcis on epigraphic grounds. For a very interesting discussion see Boardman, BSA lii (1957), 12–14. Eleni Walter-Karydi in CVA, Munchen, vi (1968), 23 f., describes the class as Inselionisch’, regarding it as deriving from the ‘Melian’ group which, following Kontoleon, she thinks was produced on Paros.Google Scholar

4 202; Rumpf, Chalk. Vas. 8 and 46, no. 3, 65 f., pls. 6–9.

5 Not named on any vase, but characterized (two heads, snake-headed tail) by Euphronios and others (see below). Hesiod calls him Orthos, later writers generally Orthros. See West on Theog. 293 (pointing out that he was Geryones’ cousin) and Roscher s.v. Orthros.

1 See further below. On separate pictures not framed off from each other cf. Robertson, GP 77.

2 B 155; Rumpf, loc. cit. 10 and 47, no. 6, 65 f., pls. 13–15.

3 On Cab. Méd. 202 the near wing is certainly on the outermost left shoulder but one cannot see where the other one springs. On B.M. B 155 the wings seem to belong to different bodies, but the painter is concerned to suggest the giant collapsing in confusion and the detailed structure will not stand up to examination. Dikaiopolis’ challenge to Lamachus (Ar. Ach. 1082)![]() .

.

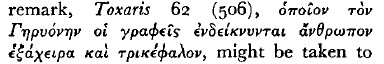

4 On the Paris vase the painter has given the figure two left feet, but it would be a mistake to suggest that this was deliberate and that he meant to imply four more legs, one left and three right, concealed behind. Had that been his intention he would have distinguished left and right and trebled the outline; cf. two Boreads chasing two Harpies on the Laconian cup from Caere in the Villa Giulia, Robertson, GP 70. Confusion of left and right occurs surprisingly often in black-figure and red-figure vase-painting, even in very good work like this (for examples in red-figure see JHS ixxiv (1954), 229 f.);Google Scholar it seems connected with the fact that the whole figure was drawn first in silhouette, the detail then added as a separate operation. On the metope from the Athenian Treasury at Delphi (above, p. 207 n. 6) the bodies are complete, as are those of the Hephaisteion metope. In the no less ruined metope at Olympia, of the second quarter of the fifth century (above, p. 207 n. 7) it does look as though the artist had adopted the form with only one pair of legs, but in fact he has achieved this effect by concealing the further pairs behind the shield of a collapsing body, from whose head the helmet has fallen (cf. pap. fr. 4. i. 14–17, LGS 56E). Lucian's  imply this type, but the context makes it clear that he had three complete bodies in mind. The type dividing only above the hips does appear on a fourth-century Apulian vase (Gerhard, Apul. Vas. pl. to) and again in Roman art, alongside that with three full bodies and a type (also found on a South Italian vase, Millingen, pl. 27 and evidently envisaged by Hesiod) with three heads alone (see Robert, , Ant. Sark. iii. 1.119);Google Scholar and again in a fresco of the Labours in the Vatican by a follower of the Pollaiuoli (Berenson, Italian Pictures of the Renaissance: Florentine School, 1963, fig. 790); here too one body falls stricken while the others fight on. A strange avatar of Geryones is as the spirit presiding over the second of the three lowest regions of Dante's Hell, the circles of those who sinned by fraud. His triplicity makes him a natural symbol of deceit, and Mr. Colin Hardie suggests to me that Dante may have been impressed by Servius’ coupling, in his commentary on forma tricorporis umbrae (Aen. 6. 289), of the three-bodied Geryon with Erylus who had three souls. He gives him, however, a triple form of medieval character, derived from the Locusts of Revelation and Pliny's mandricola. Quella sozza imagine di frode has the face of a just man, foreparts and shoulders of a hairy beast, the rest a marbled snake. He can fly, but not on wings, which would add a fourth element. The poet makes it clear that he swam through the thick atmosphere with paws and tail; but the point is not taken by all his illustrators (e.g. Lorenzo, Vecchietta in Pope-Hennessey, , A Sienese Codex of the Divine Comedy, Oxford, 1947, pl. 20), although they, unlike the vase-painters, were setting out to illustrate a text—a relevant point.Google Scholar

imply this type, but the context makes it clear that he had three complete bodies in mind. The type dividing only above the hips does appear on a fourth-century Apulian vase (Gerhard, Apul. Vas. pl. to) and again in Roman art, alongside that with three full bodies and a type (also found on a South Italian vase, Millingen, pl. 27 and evidently envisaged by Hesiod) with three heads alone (see Robert, , Ant. Sark. iii. 1.119);Google Scholar and again in a fresco of the Labours in the Vatican by a follower of the Pollaiuoli (Berenson, Italian Pictures of the Renaissance: Florentine School, 1963, fig. 790); here too one body falls stricken while the others fight on. A strange avatar of Geryones is as the spirit presiding over the second of the three lowest regions of Dante's Hell, the circles of those who sinned by fraud. His triplicity makes him a natural symbol of deceit, and Mr. Colin Hardie suggests to me that Dante may have been impressed by Servius’ coupling, in his commentary on forma tricorporis umbrae (Aen. 6. 289), of the three-bodied Geryon with Erylus who had three souls. He gives him, however, a triple form of medieval character, derived from the Locusts of Revelation and Pliny's mandricola. Quella sozza imagine di frode has the face of a just man, foreparts and shoulders of a hairy beast, the rest a marbled snake. He can fly, but not on wings, which would add a fourth element. The poet makes it clear that he swam through the thick atmosphere with paws and tail; but the point is not taken by all his illustrators (e.g. Lorenzo, Vecchietta in Pope-Hennessey, , A Sienese Codex of the Divine Comedy, Oxford, 1947, pl. 20), although they, unlike the vase-painters, were setting out to illustrate a text—a relevant point.Google Scholar

1 M. 340; Beazley, ABV 108, no. 14 and 685, with refs.; Dev. 48; Rumpf, Sak., pls. 13a, 15 a-b, and pp. 11 and 27, no. 76.

2 ARV 2 62, no. 84; des Vergers, L'Étrurie et les Étrusques, pl. 38; Klein, Euphronios 81.

3 2620; Beazley, ARV 2 16 f. and 1619, no. 17, with refs.; FR, pl. 22; Pfuhl, MuZ, fig. 391; Lullies and Hirmer, GVRZ, pls. 12–16.

1 See further below.

2 Ibid., p. 7. The arrow in the eye appears in the r.f. cup-fr. Acr. 46 (above, no. 9).

3 Ibid., p. 6. On the early classical metope at Olympia (above, p. 207 n. 7) the one surviving head, from a falling body, upsidedown and almost touching the ground, is bare.

4 Eurytion, as Lobel notes, is ruled out by the crested helmet.

1 Above, p. 207 n. 4.

2 Above, p. 207 n. 3.

4 Johansen, loc. cit., pl. 30, i; Payne, PV, pl. 21.

3 Above, p. 207 n. 2.

1 The bridegroom with skin, quiver, and I think club on the ‘Melian’ vase mentioned in p. 219 n. 4 cannot be other than Herakles, and the vase cannot be much after the beginning of the sixth century. A very similar figure of the same time or not much later, on a Chiot fragment of the ‘Chalice style’ from the Acropolis of Athens (Graef no. 450, pls. 15 and 24; Pfuhl, MuZ, fig. 119), has skin and club and probably had also a bow. On a contemporary Attic lekythos from Corinth in London (B 30, ABV 11, Manner of the Gorgon Painter no. 20; Walters, Cat. ii. pl. I) Herakles attacks Nessos with a club but has not skin or bow; and it is only in the second quarter of the century that the type becomes regular in Attic black-figure.

2 Euphronios gives the nearest body a shield with the device of a winged boar—a rather rare motive, and drawn with unusual care. It seems just possible that there is an allusion here to the winging of the giant. See also p. 209 n. 3. The second shield has a polyp, well chosen for the ogre of many limbs.

3 See below.

4 Neck-amphora, Bologna GM 3, not in ABV, CV fasc. 2, pl. 12, 3 and 4; neck-amphora, Cabinet des Médailles, ABV 308, Swing Painter, no. 77 with refs., CV fasc. 1, pls. 38, 4–5 and 39, 1–3 and 5. In the second there are two arrows in one of the hound's heads.

5 2. 5. 10.

6 e.g. Los Angeles County Museum A 5832. 50. 137; Clement, IOC. cit., n. 9, pls. Ia, 2a (not in ABV).

7 London B 194; ABV 136, Group E, no. 56; Clement loc. cit., pl. 4 a-b. 8 F. 53; ABV 136, Group E, no. 49, with refs.; Pfuhl, MuZ, fig. 226; Clement, loc. cit., pls. 4d, 5.

1 e.g. neck-amphora Cabinet des M´dailles 223, above, p. 213 n. 4; cup Villa Giulia 1225, CV fast. 3, III H e, pls. 29, 30. and 2. See below.

2 See particularly Beckel, , Götterbeistand i.d. Bildüberlieferung gr. Heldensagen (1961).Google Scholar

3 Cadmus: Page, PMG fr. 18; Epeios: ibidem., fr. 23. On the papyrus evidence for her intervention here see below.

4 Gerhard, AV, pl. 104.

5 Cup in Villa Giulia, n. 1 above. She is also shown on the other vase mentioned in that note.

6 She is unwinged (and named) on the ![]() Vase, her earliest appearance in art, and unwinged (but not named) on the red-figure cup cited in p. 218 n. 1. ‘Greek artists are ready to wing and unwing at need’ (Beazley, Attic Black-figure, a Sketch, 21).

Vase, her earliest appearance in art, and unwinged (but not named) on the red-figure cup cited in p. 218 n. 1. ‘Greek artists are ready to wing and unwing at need’ (Beazley, Attic Black-figure, a Sketch, 21).

7 e.g. stamnos Louvre G 192, ARV 2 208, Berlin Painter no. 160, with refs.; CV, pl. 55. A, infant Herakles strangling the snakes (Athena present); B, Zeus dispatching Hermes and Iris.

8 The vase in n. 4 above; Berkeley 8/3851, CV, pl. 21A; B.M. B 156, CV, nl. 27. 1; B.M. B 426, CV, text, 0. 8. ABV 256, Lysippides Painter no. 20. In the last she runs between the combatants and supplicates Athena. She was also shown on the fragmentary red-figure cup in the Villa Giulia and Heidelberg, above, p. 208 n. 2.

1 Mr. Colin Hardie points out to me that it would ease the interpretation of pap. fr. 3 if one could suppose that Kallirhoe was present also, and the words spoken to Poseidon were hers.

2 Klein, Euphronios 52; Furtwängler FR i. 102.

3 2. 5. I I.

4 Aen. 4.484; Merkelbach and West, fr. 360.

5 4. 1399. Apollonius Rhodius himself (4. 1427) calls her Erythreis.

6 10. I 7. 5. Stephanus of Byzantium (s.v.) quotes him, but there is no independent confirmation.

7 See Seelige in Roscher s.v., 2597.

8 Theog. 293; Fr. Gr. Hist. i. 134 (Hellanicus 110).

9 On Aen. 8. 299.

1 See above (p. 213 n. 5).

2 x. 1.62.2. 5. 3 f.

2 133, 8431b15–844a5 (Arist. Minor Works, ed. W. S. Hett, 304–7); Huxley, in Gr. Rom. and Byz. Studies viii (1967), 88–92.Google Scholar

3 BSA xxxii (1931/1932), 158.Google Scholar

4 Fr. Gr. Hist. i F 26.

5 See p. 214 n. 8.

6 e.g.: Memnon rushing on his fate, Beazley, Berliner Maler, pls. 29 f. (B.M. E 468; ARV 2 296, no. 132); the death, AJA lxii (1958),Google Scholar pl. 6, fig. 2 (Agora P 24113; ARV 2 213, no. 242); the body, Pfuhl, MuZ, fig. 466 (Louvre G 115; ARV 2 434, no. 74).

7 e.g. Technau, Exekias, pl. 3a (Berlin 1718; ABV 144, no. 5).

1 Pfuhl, MuZ, fig. 345 (B.M. E 12; ARV 2 126, no. 24).

2 Louvre G 17; ARV 2 62, no. 83, with refs.; CV, fasc. to, m lb, pls. 5. 1, 6. 4.

3 B.M. E 44; ARV 2 318 f., no. 2, with refs.; Pfuhl, MuZ, fig. 401.

4 See West on Theog. 351. I do not know if there is any certain representation of the Attic Kallirrhoe, but it has sometimes been suggested that the figure W in the south corner of the west pediment of the Parthenon, corresponding to the `Ilissus' in the north corner, may, if the other be really a river-god, be the nymph of the city's most famous spring. I like to think that this may be so, and that here too she may be identified with the mother of Geryones, the figure who squats beside her being Chrysaor. Thus the ‘family-group’ atmosphere, so marked in the figures from the royal houses of Athens which occupy most of the pediment-wings, would be extended to the local personifications framing the scene. For a quite different interpretation, however, most persuasively argued, see E. Harrison, ‘U and her neighbours in the west pediment of the Parthenon’, in Essays in the History of Art Presented to Rudolf Witkower, especially n. 55.

5 See above, p. 208 n. 5.

6 Forms of the word ![]() as Mr. Barrett points out to me, occur in two of the papyrus-fragments: 17. 8

as Mr. Barrett points out to me, occur in two of the papyrus-fragments: 17. 8 ![]() in a context of

in a context of ![]() and 41, an unintelligible scrap. Neither gives any ground for postulating a chariot of Herakles in the story.

and 41, an unintelligible scrap. Neither gives any ground for postulating a chariot of Herakles in the story.

7 e.g. the b.f. jug signed by the potter Kolchos, Berlin 1732 from Vulci, ABV 1 to, Lydos no. 37, with refs.; Rumpf, Sak., pls. 29–31: Pfuhl, MuZ, fig. 242. See Brommer, Vasenlisten and mythological indexes to ABV and ARV 2.

1 58–120, 321–4, 338–48, 368–72, 463–70.

2 Payne, NC 126 ff.; nos. 1–5, figs. 45 A-C.

3 See Brommer, Vasenlisten and mythological indexes to ABV and ARV 2. E.g. amphora Munich 2302 from Vulci, ABV 294 Psiax, no. 23, with refs.; CV, pls. 153–4

4 ‘Melian’ amphora, Athens 354, of perhaps c. 600 B.C., Pfuhl, MuZ, fig. 110.

5 Mid-seventh cent., Attic amphora, New York II. 210. I, Richter, MM Handbook, pl. 27b; Beazley, ABFS, pl. 2.

6 See Brommer, Vasenlisten and mythological indexes to ABV and ARV 2. Athena: e.g. b.f. amphora, Cambridge, 32. to, ABV 141, Towry White Painter no. 1, CV ii, pls. 22, 2; 28, 5–6. Hebe: b.f. hydria, New York, 14. 105. to, ABV 261, Manner of Lysippides Painter no. 37, Bull. MM. to, 123, fig. 2.

7 Pherecydes, ap. Ath. I I. 470 c, quoted by Page, PMG, Stesichorus, fr. 8.

8 B.f. oenochoe Boston o3. 783 from S. Italy, ABV 378, Leagros Group no. 252; Haspels ABFL, pl. 17, 3. R.f. cup in Vatican from Vulci, ARV 2 449, Manner of Douris no. 2. The oenochoe is of the same date as the later Geryones pictures; the cup later, two or three decades into the fifth century. To this period belong also late black-figure pictures of Herakles and the Sun (Haspels, ABFL, pls. 17, Ia-c; 32, sa-d; Taranto, CV 2, pl. to). In none of these does the hero shoot at the god, a story which was told by Pherekydes (Fr. Gr. Hist. 1. 18 Jac., quoted on PMG, Stesichorus fr. 8) but we do not know if it was in Stesichorus.Google Scholar

9 Euphronios 57; Diod. 4. 17. 18.

10 Haspels, , BCH liv (1930), 5 and 23 ff.; cf. Beazley, ARV 2 399 middle and 1698 Addenda to pp. 1557–8.Google Scholar

11 Basle, Antikenmuseum; ABV 60. Related to C Painter no.6; Schefold, Meisterwerke Gr. Kunst. 150 f. no. 130, with pictures. There dated c. 570–60; it may not be quite so early, but it is hard to suppose it painted much after the mid century, or the Euphronios cup much before 510. The more immediately recognizable extract from the story—Herakles and the cattle—is found only on vases of the late sixth century (p. 207 n. 5 above).

1 P. de La Coste-Messelière, Delphes, pl. 41.

2 iv. 2.

3 Nem. 4. 27.

4 Roscher i. 256, s.v. He is connected with cattle. Pindar (Isth. 6. 32–3) calls him ![]() while Apollodorus (1. 6. 1) says that he drove the cattle of Helios from Erytheia. (Yet another herd kept on Erytheia was that of Hades, whose herdsman Menoites it was, according to Apollodorus, that warned Geryon that Herakles was killing Orthros and Eurytion.) Late sixth-and early fifth-century vases (Bronuner, Vasenlisten 2 3–5) show Alkyoneus (some times named) as a giant asleep, Herakles approaching him with bow or club, sometimes Hypnos lulling him. A late black-figure cup in Tarquinia (AZ 42 (1884), pl. 3; ABV 654, no. I I) seems to illustrate a version related to Pindar's: on one side the giant asleep, Hypnos at his head, Athena behind him, an unidentifiable figure (the style is execrable) making off behind her, Herakles followed by a warrior (Telamon) approaching; on the other three oxen and two chariots. See Andreae, , JdI lxxvii (1962), 130 ff.Google Scholar

while Apollodorus (1. 6. 1) says that he drove the cattle of Helios from Erytheia. (Yet another herd kept on Erytheia was that of Hades, whose herdsman Menoites it was, according to Apollodorus, that warned Geryon that Herakles was killing Orthros and Eurytion.) Late sixth-and early fifth-century vases (Bronuner, Vasenlisten 2 3–5) show Alkyoneus (some times named) as a giant asleep, Herakles approaching him with bow or club, sometimes Hypnos lulling him. A late black-figure cup in Tarquinia (AZ 42 (1884), pl. 3; ABV 654, no. I I) seems to illustrate a version related to Pindar's: on one side the giant asleep, Hypnos at his head, Athena behind him, an unidentifiable figure (the style is execrable) making off behind her, Herakles followed by a warrior (Telamon) approaching; on the other three oxen and two chariots. See Andreae, , JdI lxxvii (1962), 130 ff.Google Scholar

1 Isth. 6. 31--5.

2 Ars Antigua A.G. Luzern, Aukt. III, 29 April 1961, pl. 37, 91; now in Hobart.

3 Od. 21. 286.

4 In the Hesiodic Catalogue Herakles sacks Pylos and kills three of Neleus’ twelve sons, but Nestor happens to be away and so escapes (Merkelbach and West, Fragmenta Hesiodea, no. 35). Some such story could easily lead to Philostratos’ version that Herakles deliberately spared him. (I owe this reference to Professor Lloyd-Jones.) If Nestor is present on Euphronios’ cup, one would like to think he is the boy with the cup on his shield.