Article contents

The Language of Virgil and Horace1

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 11 February 2009

Extract

As in literature poetry precedes prose, so in poetry a special and ‘heightened’ diction seems to precede everyday language. Mr.T.S.Eliot has put it thus: ‘Every revolution in poetry is apt to be, and sometimes to announce itself as, a return to common speech.’ How does this apply to Greek and Latin ? There are objections to considering words in isolation from this point of view, since neutral ones are apt to go now grey, now purple, according to their company; but if we do not do so, we deny ourselves the only considerable method of investigation (unsatisfactory though it is) that is still open to us. Again, we must recognize that most poems are composed largely of ordinary words, though these are often used in a way that is not ordinary.

Information

- Type

- Research Article

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Classical Association 1959

References

page 181 note 2 See Jespersen, O.,language(1922), p.432.Google Scholar

page 181 note 3 The Music of Poetry (1942), p. 16.Google Scholar

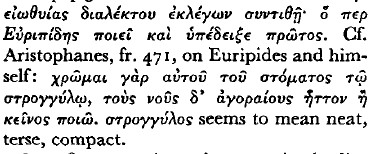

page 181 note 4 1404b5 ![]()

![]()

.

.

page 181 note 5 1458a–1459a ‘mean’-![]() , ‘ordinary’-

, ‘ordinary’-![]() , ‘unusual’-

, ‘unusual’-![]() . Oddly enough, the first example he gives of the virtue of unusual diction is a line of Aeschylus,

. Oddly enough, the first example he gives of the virtue of unusual diction is a line of Aeschylus,![]() , which was redeemed from the banal (

, which was redeemed from the banal (![]() ) to the noble (

) to the noble (![]() ) by Euripides, who heightened

) by Euripides, who heightened ![]() . For other instances of far from ordinary language in Euripides see Earp, F.R., The Style of Aeschylus (1948), p. 72.Google Scholar

. For other instances of far from ordinary language in Euripides see Earp, F.R., The Style of Aeschylus (1948), p. 72.Google Scholar

page 181 note 6 1404b1–5.

page 181 note 7 The literal Latin for ![]() is collo-catio, and this is also ambivalent, since it can refer either to arrangement of topics, or to fitting together of words, usually with a view to

is collo-catio, and this is also ambivalent, since it can refer either to arrangement of topics, or to fitting together of words, usually with a view to ![]() , concinnitas. The word is also rendered by compositio, as in the title of Dionysius’

, concinnitas. The word is also rendered by compositio, as in the title of Dionysius’ ![]() .

.

page 182 note 1 XL.

page 182 note 2 The inappropriateness was remarked by Immisch, O., Horazens' Epistel über die Dicht-kunst (1932), p. 83 n.Google Scholar

page 182 note 3 Of course, for all we know, ![]() may be an unpoetic phrase.

may be an unpoetic phrase.

page 182 note 4 Cic. Brut. 253. Cf. Tac. Dial. 22.

page 182 note 5 Or. 163: Verba … legenda sunt potissimum bene sonantia; sed ea non ut poetaeexquisita ad sonum, sed sumpta de medio. Cf. De Or. 1. 12.

page 183 note 1 Or. 36: Ennio defector quod non discedit a communi more uerborum.

page 183 note 2 For the modern situation see Fraser, G.S, ‘Writing’, in A New Outline of Modem Knowledge, ed. Jones, A.Pryce (1956), p. 329.Google Scholar

page 183 note 3 ii. 275. 9 Hausrath.

page 183 note 4 Catalepton V. Servius on Aen. 6. 264; Eel. 6. 13. Probus, Vita Verg. p. 73. 10 Br. Cic. De Fin. 2. 119. Philodemus, Pap. Herc. 312; Crönert, W., Kolotes und Menedemos (1906), p. 126Google Scholar. Rostagni, , L'Arte Poetica di Orazio (1930), p. xiiiGoogle Scholar, says that Philodemuss probably addressed one of his works to Horace, along with Virgil, Varius, and Quintilius Varus. But it is more than likely that the corrupt name in ![]() should be restored as

should be restored as ![]() rather than

rather than ![]() (as he admits elsewhere, p. xxix n.). Plotius et Varius Sinuessae Vergiliusque occurrere, says Horace on his journey to Brundisium (S. 1. 5. 40); and Plotius Tucca is inseparable from Varius, while Horace is hardly likely to have known the circle in the period when it seems to have centred round Siro (c. 50–40 B.C.).

(as he admits elsewhere, p. xxix n.). Plotius et Varius Sinuessae Vergiliusque occurrere, says Horace on his journey to Brundisium (S. 1. 5. 40); and Plotius Tucca is inseparable from Varius, while Horace is hardly likely to have known the circle in the period when it seems to have centred round Siro (c. 50–40 B.C.).

page 183 note 5 S.I. 2. 121.

page 183 note 6 Ant. Rom. 1. 7.

page 184 note 1 Marx, F., Rh. Mus. lxxiv (1925), 185–8Google Scholar;Immisch, , op. cit., pp. 86–90.Google Scholar

page 184 note 2 Suas. 1. 12.

page 184 note 3 Odes, 1. 6.

page 184 note 4 N.H. 34. 62; 35. 26.

page 184 note 5 ‘M. Agrippa und die zeitgenössische römische Dichtkunst’, pp. 174–94.Google Scholar

page 184 note 6 La Lingua di Orazio (Florence, 1930)Google Scholar. Büchner, K., Report on Horace in Bursian Jahresberichte (1939), pp. 53–56.Google Scholar

page 184 note 7 pp. 65–91. Büchner, , op. cit., p. 58Google Scholar.There are also some valuable observations in Leumann, M., Die lateinische Dichtersprache (Mus. Hel. 1947), pp. 116 ff.Google Scholar

page 184 note 8 See, e.g., Leo, F., ‘Römische Literaturgeschichte’, in Kultur der Gegenwcrt, 1. 83, p. 445. Hor. S. 1. 4. 39–44; Ep. 2. 1. 250–1.Google Scholar

page 185 note 1 See Sandbach, F.H. in C.R. liv (1940), 196–7.Google Scholar

page 185 note 2 p. 151.

page 185 note 3 Quint. 1. 7. 18.

page 185 note 4 p. 29.

page 185 note 5 pp. 67–68.

page 185 note 6 p. 29.

page 185 note 7 1. 6. 40; 8. 3. 24: eoque ornamento acerrimi iudicii P. Vergilius unice usus est.

page 185 note 8 Cordier, , p. 150.Google Scholar

page 185 note 9 pp. 222–3, 230, 234, 270. The figure for Lucretius is 1 -3: p. 232.

page 185 note 10 Nor does Meillet, A. in his Esquisse d'une histoire de la langue latine (1953)Google Scholar, nor Marouzeau, J. in his Traité de stylistique latine (1945)Google Scholar, though the meagre indexing of even the most important French works makes it hard to verify a negative statement. W. F. Jackson Knight, in his suggestive Chapter V, says briefly: ‘It was partially at least a mixed style out of countless spoken and witten idioms of different places and ages. The Romans of the time liked it immediately. Agrippa, who thought it rather a grotesque and dishonest style, was very much in the minority.’ Roman Vergil (1944), p. 261.Google Scholar

page 186 note 1 PP.314–16.

page 186 note 2 G. 3. 290. Immisch, (op. cit., p. 88) connects Agrippa's remark with Porphyrion's note on Horace, A.P. 47 (callida iunctura), which gives as an example G. 1. 185: Namlicet aliqua uulgaria sint, ait tamen ilia cum aliqua compositione splendescere. Verbi gratia ‘curculio’ sordida uox est, ornatu antecedente uulgaritas eius absconditur hoc modo: ‘populatque ingentem farris aceruumcurculio’.Google Scholar

page 186 note 3 Rostagni rightly stresses that Horace is here dealing with ![]() (not

(not ![]() )

) ![]() ; but it seems gratuitous to follow him in deriving serendis from serere ‘to sow’ rather than serere ‘to weave’. The latter was a common metaphor for literary composition, and its use with iunctura here is echoed by series iuncturaque in the same sense in 11. 242–3.

; but it seems gratuitous to follow him in deriving serendis from serere ‘to sow’ rather than serere ‘to weave’. The latter was a common metaphor for literary composition, and its use with iunctura here is echoed by series iuncturaque in the same sense in 11. 242–3.

page 186 note 4 Quint. 9. 4. 32 ff. Immisch, (op. cit., p. 80) takes it so here.Google Scholar

page 186 note 5 Of course uerba nouare can mean to create new words as by compounding-expectorare, uersutiloquus-or otherwise, senius desertus, dii genitales, bacarum ubertate incuruescere, Cic. De Or. 3. 154.

page 187 note 1 I agree with Rostagni that he is still treating of diction.

page 187 note 2 Compare this application of the doctrine of ![]() (Arist. Rhet. 3. 7) with the observation at 11. 95–98 that Euripides' Telephus, when poor and in exile, rightly uses sermo pedestris, not tragic grandiloquence, in his complaints.

(Arist. Rhet. 3. 7) with the observation at 11. 95–98 that Euripides' Telephus, when poor and in exile, rightly uses sermo pedestris, not tragic grandiloquence, in his complaints.

page 187 note 3 A.P. 7. 50, by Archimedes, or Archimelus (third cent. B.C.).

page 187 note 4 Ch. 76. Cf. Hor. Ep. 2. 124: ludentis speciem dabit et torquebitur.

page 187 note 5 Epp. 2. 2. 109–25.

page 187 note 6 Ch. 150: in propriis igitur est ilia laus orationis, ut abiecta atque obsoleta fugiat, lectis atque illustribus utatur, in quibus plenum quiddam et sonans inesse uideatur.

page 188 note 1 Unpoetische Wörter, ch. 4, pp. 98–113. Axelson does not mention Agrippa's remark in this connexion, but he refers to Marx';s article in his Introduction, p. 15.Google Scholar

page 188 note 2 pp. 108–10.

page 188 note 3 p. 63.

page 188 note 4 10. 1. 96.

page 188 note 5 Frena licentiae iniecit (4. 15. 10), apricos flores (1. 26. 7). Here are some more metaphors. Verbs: spem resecare (1. 11. 7); merocaluisse uirtus (3. 21. 12); sacrare plectro (1. 26.11); merces defluat (1. 28. 27); te bearis nota Falerni (2. 3. 8); uoltus adfuhit (4. 5. 6); diemmero fregi (2. 7. 6); transiliat munera Liberi (i. 18. 7); carpere obliuiones (4. 9. 33). Laudes deterere (1.6. 12) and Notus deterget nubila (1. 7. 15) are instanced by Heinze ad A.P. 47. Nouns: Carminis alite (1. 6. 2: Heinze); copia narium (2. 15.6); inimice lamnae (2. 2. 2); plenum opus aleae (2. 1.6). Adjectives: auream mediocritatem (2. 10. 5); uultus lubricus adspici (1. 19. 8); sepultae inertiae (4. 9. 29); pigris campis (1. 22. 17).

page 188 note 6 1.4. 20; 4. 9. 11.

page 188 note 7 1. 27. 15.

page 188 note 8 2. 15. 16; cf. excipere aprum (3. 12, fin.) and our phrase ‘a sun-trap’.

page 189 note 1 Socraticis madet sertnonibus (3. 21. 9); munitaeque adhibe uim sapientiae (3. 28. 4); conuerso inpretium deo (3. 16. 8).

page 189 note 2 3. 1. 30, fundusque mendax, arbore nunc aquas culpante ….

page 189 note 3 2. 15. 4, caelebs; 2. 9. 8, uiduantur; 1. 36. 20, lasciuis hederis ambitiosior, 1. 12. 11, auritas.

page 189 note 4 1. 25. 11, bacchante; 3. 27. 20, peccet; 1. 25. 20, sodati; 1.3. 15, arbiter.

page 189 note 5 1. 14. 8, imperiosius; 1. 2. 20, uxorius; 1. 31. 8, mordet.

page 189 note 6 3. 8. 11, institutae; 4. 12. 17, eliciet. Other examples: 1. 25. 3, amat ianua limen; 4. 11. 7, ara auet spargier; 4. 11. 6, ridet argento domus; 1. 14. 5, malus saucius.

page 189 note 7 2.9.1–10:2.3.9–16; 1.9throughout;?cf. Epode 13. 1–5. Wilkinson, L.P., Horace and his Lyric Poetry, pp. 126–31.Google Scholar

page 189 note 8 4.13.8, Cupido excubat in genis, cf.Antig. 782; I. 18. 16; 3. 1. 40.

page 189 note 9 4. 9. 39; 2. 16. 9; 2. 18. 40, uocatus atque non uocatus audit.

page 189 note 10 1. 15. 19, 31; 1. 28. 32. Also 3. 2. 16 timido tergo; 3. 5. 22 tergo libera; 1. 17. 28 immeritam uestem.

page 189 note 11 3.11.35; 1.34.2; 1. 14.17.Also 1.22. 16, arida nutrix; 3. 21. 13, lene tormentum.

page 189 note 12 1. 27. 11, beatus uolnere; 1. 33. 14 and 4. 11. 23, grata compede; 2. 12. 26, facilisaeuitia; cf. 1. 8. 2, amando perdere.

page 189 note 13 Op. cit., p. 110.Google Scholar

page 189 note 14 Goethes Gespräche, Biedermann2, 1. 458. E. Castle has suggested that furchtbare is amisprint for fruchtbare. Mitteil d. Verein d. Freunded. human. Gymnasiums, 33. Heft, Wien, 1936, p. 14Google Scholar. ‘Formidable’ is Prof. Fraenkel's word (Horace, p. 276); otherwise an English reader might assume from the context that Goethe meant ‘frightful’.Google Scholar

page 190 note 1 45–50 iii. One may doubt, however, whether occupat nomen or callet uti are phrases of ordinary prose.

page 190 note 2 Op.cit., p. 67.Google Scholar

page 190 note 3 Conington-Nettleship-Haverfield, i5, pp. xxix–liii.

page 190 note 4 Vita Verg. 43–46.

page 190 note 5 6. 6. 1: quae in Vergilio notauerit ab ipso figurata, non a ueteribus accepta, uelausu poetico noue quidera sed decenter usurpata. Ausu recalls Quintilian's characterization of Horace as ‘uerbis felicissime audax’.

page 190 note 6 3; A 9.455.

page 190 note 7 6–7; A. 7.417.

page 190 note 8 18; G. 4. 136; E. 4. 20. But in Greek we have ![]() in Meleager, A.P. 5. 147 (

in Meleager, A.P. 5. 147 (![]() , Giangrande, , Rh. Mus. 1958, p. 54); cf. A.P. 5. 144. 5.Google Scholar

, Giangrande, , Rh. Mus. 1958, p. 54); cf. A.P. 5. 144. 5.Google Scholar

page 191 note 1 A. 2. 422, mentitaque tela; 9. 773, fer-rumque armare ueneno; G. 2. 36, cultusque feros mollire colendo; ib. 51, exuerint siluestrem ani-mum; A. 11. 804, uirgineumque alte bibit acta cruorem (cf. II. 21. 168); G. 2. 59, pomaque degenerant sucos oblita prions; A. 4. 67, taciturn uiuit sub pectore minus; A. 5. 681, duro sub robore uiuit stuppa uomens tardum fumum; Ib. 257, saeuitque canum latratus in auras; 7. 792, caelataque amnem fundens pater Inachus uma; G. 4. 239, animasque in uulnera ponunt.

page 191 note 2 ‘Thoughts on Virgil, 's Bimillenary’, in the Nineteenth Century, Oct. 1930, pp. 512–13.Google Scholar

page 191 note 3 5. 14. 5: uolsis ac rasis similes et nihil differentes ab usu loquendi. Nettleship remarks (ib. p. xxx) that uolsis ac rasis has all the air of a quotation from a hostile critic.

page 191 note 4 G. 3. 4; E. 6. 75; Gellius 2. 6 =Macrobius 6. 7. 4–5; Seru. on A. 10. 547; Cornutus ut sordidum improbat.

page 191 note 5 Op. cit., p. 263.Google Scholar

page 192 note 1 In the time of the elder Seneca there were still those who ![]() (Contr. 9. 26).

(Contr. 9. 26).

- 2

- Cited by