Article contents

More Notes on Euripides' Electra

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 11 February 2009

Extract

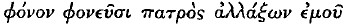

Orestes has returned to Argos,  (89). For him to brandish

(89). For him to brandish  at his father's murderers is natural there, where he is delivering a sort of general manifesto as to his aims, and where the strong word

at his father's murderers is natural there, where he is delivering a sort of general manifesto as to his aims, and where the strong word  is justified and alleviated by the jingle with

is justified and alleviated by the jingle with  juxtaposed (‘to requite them murder as they murdered my father’). But there is no reason for Orestes to go on insisting on the bloodthirstiness of these aims, and

juxtaposed (‘to requite them murder as they murdered my father’). But there is no reason for Orestes to go on insisting on the bloodthirstiness of these aims, and  reads oddly in 100, where he is explaining soberly his plan of campaign.

reads oddly in 100, where he is explaining soberly his plan of campaign.

Information

- Type

- Research Article

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Classical Association 1966

References

page 51 note 1 Cf. C.Q. N.S. x (1960), 129–34.Google Scholar

page 51 note 2 It is only by subsequent developments in the play that she in fact becomes ![]()

![]() cf. 276–9, and 646–7 Op.

cf. 276–9, and 646–7 Op. ![]()

![]()

![]() .

.

page 52 note 1 For the survival, in the Greek judicial trial, of elements of the ordeal (in the form of special oaths, Eideshelfer, torture of slaves, ![]() , and so on) cf. Glotz, , Études sociales et juridiques sur l'antiquité grecque, pp. 93 f.Google Scholar, Gernet, , Droit et société dans la Grèce ancienne, pp. 62ff.Google Scholar Because of the atmosphere of ordeal surrounding the Greek trial the word

, and so on) cf. Glotz, , Études sociales et juridiques sur l'antiquité grecque, pp. 93 f.Google Scholar, Gernet, , Droit et société dans la Grèce ancienne, pp. 62ff.Google Scholar Because of the atmosphere of ordeal surrounding the Greek trial the word ![]() (originally = the assembly in or before which trials, games, ordeals, and the like were held, then such trials or competi tions themselves) acquires its familiar classical sense of a critical situation, in which one stands to gain or lose a lot: cf. Ant. 6. 3

(originally = the assembly in or before which trials, games, ordeals, and the like were held, then such trials or competi tions themselves) acquires its familiar classical sense of a critical situation, in which one stands to gain or lose a lot: cf. Ant. 6. 3 ![]()

![]() .

.

page 52 note 2 The legalistic ![]() readily becomes, in the Greek imagination, a competitive or athletic one: cf. 883

readily becomes, in the Greek imagination, a competitive or athletic one: cf. 883 ![]()

![]()

![]() and 1264

and 1264 ![]()

![]() (of Orestes' trial before the Areopagus); Aesch. Agam. 343 f.

(of Orestes' trial before the Areopagus); Aesch. Agam. 343 f. ![]()

![]() , of the expedition to Troy which has previously been described in legalistic terms (cf. 40 f.

, of the expedition to Troy which has previously been described in legalistic terms (cf. 40 f. ![]() The historical interconnexion between games and judicial trials is discussed by Gernet, op. cit. 9 ff. (‘Jeux et Droit (remarques surle xxiiie chant de I'lliade)’).

The historical interconnexion between games and judicial trials is discussed by Gernet, op. cit. 9 ff. (‘Jeux et Droit (remarques surle xxiiie chant de I'lliade)’).

page 52 note 3 Strictly, ![]() were thieves or burg lars, cf. Ant. 5. 9

were thieves or burg lars, cf. Ant. 5. 9 ![]()

![]() . But there was a tendency, both in theory and in practice, to apply the term to criminals of any sort, as this speech of Antiphon (cf. 10

. But there was a tendency, both in theory and in practice, to apply the term to criminals of any sort, as this speech of Antiphon (cf. 10 ![]()

![]() ) and the Aeschines passage show,

) and the Aeschines passage show, ![]() (though not strictly equivalent to

(though not strictly equivalent to ![]() , cf. Barrett, on E. Hipp. 642Google Scholar) and its derivatives were also used in the same general sense, cf. Ant. 5. 65

, cf. Barrett, on E. Hipp. 642Google Scholar) and its derivatives were also used in the same general sense, cf. Ant. 5. 65 ![]()

![]()

![]() , Soph. El. 1505–7

, Soph. El. 1505–7 ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() .

.

page 52 note 4 It is pretty clear after all—Euripides has made it pretty clear by his treatment of the theme—that Electra and Orestes are nothing like accredited legal prosecutors of Clytaemnestra and Aegisthus. They had no right to take the law into their own hands, at least as far as Clytaemnestra was concerned. Orestes is sure enough about this, cf. 975 ![]()

![]() (‘innocent’, at law, cf. the legalistic use of

(‘innocent’, at law, cf. the legalistic use of ![]() at D. 9. 44; 20. 158; 23. 55). And cf. Tyndareos' taunts, Or. 494 ff.

at D. 9. 44; 20. 158; 23. 55). And cf. Tyndareos' taunts, Or. 494 ff. ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() .Tyndareos himself proposes (609)

.Tyndareos himself proposes (609) ![]() against Orestes, i.e. to prosecute him for the murder of Clytaemnestra,

against Orestes, i.e. to prosecute him for the murder of Clytaemnestra, ![]() (iv being a tragic variant for the usual

(iv being a tragic variant for the usual ![]() .

.

page 53 note 1 Agamemnon's submission to Calchas' word diat Iphigenia should be sacrificed (cf. Aesch. Ag. 186 ![]() —‘not questioning a prophet's authority, never!’) is symptomatic, even though it was reprehensible.

—‘not questioning a prophet's authority, never!’) is symptomatic, even though it was reprehensible.

page 54 note 1 Meurig Davies cites earlier articles in C.R. by J. E. Powell, A. S. F. Gow, G. P. Shipp, and Dodds' note to Eur. Bacch. 241.

page 54 note 2 As other instances of ‘expressive’ synecdoche I would mention the following: S. Aj. 527 f. p. ![]()

![]() (the eye is put for the bird, because it expresses most vividly the fear); Tr. 527

(the eye is put for the bird, because it expresses most vividly the fear); Tr. 527 ![]()

![]() (the eye is put for Deianeira, because it expresses her timid fears, and possibly also the beauty which caused the fight between Herakles and Achelous); Ant. 944 f.

(the eye is put for Deianeira, because it expresses her timid fears, and possibly also the beauty which caused the fight between Herakles and Achelous); Ant. 944 f. ![]()

![]() , as Jebb says, because of her beauty, cf. E. Hel. 383 f.

, as Jebb says, because of her beauty, cf. E. Hel. 383 f. ![]()

![]() ; phoen. 806

; phoen. 806 ![]() (of the Sphinx). On the other hand, I do not agree with Meurig Davies that the MSS. reading

(of the Sphinx). On the other hand, I do not agree with Meurig Davies that the MSS. reading ![]() at E. El. 688 should be retained as against Geel's conjecture

at E. El. 688 should be retained as against Geel's conjecture ![]() . For

. For ![]() , so far from expressing some significent aspect, would be absurd and tasteless. Here, it seems to me, Denniston has the last word: ‘Greeks did not commit suicide by stabbing their heads, an inconvenient method.’

, so far from expressing some significent aspect, would be absurd and tasteless. Here, it seems to me, Denniston has the last word: ‘Greeks did not commit suicide by stabbing their heads, an inconvenient method.’

page 54 note 3 It may be added that the cheek, neck, and face are already associated through mourning—ceremonies: cf. Il. 19. 284–5 ![]()

![]() A. Cho. 24

A. Cho. 24 ![]()

![]() , E. El. 146 f.

, E. El. 146 f. ![]()

![]() , Or. 961

, Or. 961 ![]()

![]() .

.

- 2

- Cited by