Article contents

Avarice and Discontent in Horace's First Satire

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 11 February 2009

Extract

In Satires 1.1 Horace asks the question why people are discontented and praise the fortunes of others, and he gives the answer that they are greedy. The precise connection between question and answer is however far from clear, and some commentators have felt that Horace has combined two separate themes of avarice and discontent without establishing a causal link between them. The great obstacle for critics who argue for thematic unity is to explain how it is that the malcontents of 1–19 are motivated by greed, for Horace is not explicit but merely asserts baldly that it is so (108–9), and leaves the reader to work out the logic. The direct method is to identify to some degree praise of the fortunes of others with an envious desire to outstrip them in wealth. In support we may quote two of the most influential recent interpreters of the Satires, to whom all interested in the poems owe a great debt: ‘It is avaritia that is at the bottom of the misguided yearning after other men's lot. All those people would not be prepared to have a change; rather will they, out of greed, put up with any toil or danger.’

Information

- Type

- Research Article

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Classical Association 1980

References

1 Notably Kiessling-Hcinze, 7th edn. (Berlin, 1959), introduction to Satire 1.

2 Fraenkel, E., Horace (Oxford, 1957), p. 91.Google Scholar

3 Rudd, N., The Satires of Horace (C.U.P., 1966), p. 14.Google Scholar A modified version of the same conclusion on this point is reached by Kraggerud, E., Sytnbolae Osloenses 53 (1978), 133–64:CrossRefGoogle Scholar ‘Laudatio oder Makarismos ist, wie sich dies … in den Beispielen zeigt, auf das Andere und Fremde gerichtet. Darin ist wesentlicher Bestandteil der Wunsch, das Fremde zu bekommen und zu besitzen. Dieser Wunsch hat mit Avaritia zu tun, ja fallt mit ihr zum guten Teil zusammen … Zugleich ist Horaz darauf aus, den weiteren Weg zu bezeichnen, wenn er innerhalb jedes Paares den materiellen Neid bei einem der Berufsvertreter (miles und agricola) betont.’ The view of Herter, H., RhM 94 (1951), 1–42, who gives a very full survey of modern critics and of ancient parallels, is not entirely clear to me. He rejects avarice as the guiding idea, p. 4, and sees invidia and avaritia as parallel and complementary, both together leading to discontent, p. 37. This seems to give less than full recognition to Horace's emphasis in lines 40 and 108 ff.Google Scholar

4 Details may be seen in Kiessling-Heinze ad loc; cf. Rudd, , op. cit., p. 13: men envy the greater wealth of those in other occupations, but no mention of this envy is made in 1–12 because Horace wants to suggest that the fundamental role of greed only occurred to him in the course of writing.Google Scholar

5 Of the two main ancient parallels, Maximus of Tyre 15 ad init. treats discontent with one's own lot as basic, so that, should a miraculous change of occupation occur, people would at once be discontented with the new and yearn for the old; while ps. Hippocrates, Ep. 17 (370L), though giving special emphasis to avarice, does not clearly regard it as the sole origin of discontent. See Kraggerud, , op. cit., pp. 144–5,Google Scholar for a critique of Fraenkel's claim (op. cit., p. 93Google Scholar) that Horace found in current Cynic and similar discussions the I manifestations of discontent reduced to their primary cause, avarice.

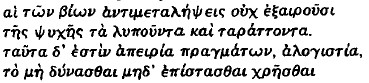

6 On Tranquillity, Mor. 466 a-d: ![]()

![]() cf. Ep. 1. 14. 10–14: ‘rare ego viventem, tu dicis in urbe beatum. cui placet alterius, sua nimirum est odio sors. stultus uterque locum immeritum causatur inique: in culpa est animus, qui se non fugit umquam.’ In our poem avarice is the particular way in which all minds are at fault.

cf. Ep. 1. 14. 10–14: ‘rare ego viventem, tu dicis in urbe beatum. cui placet alterius, sua nimirum est odio sors. stultus uterque locum immeritum causatur inique: in culpa est animus, qui se non fugit umquam.’ In our poem avarice is the particular way in which all minds are at fault.

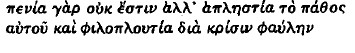

7 Plutarch, On Love of Wealth, Mor. 524 d, says of one greedy beyond need:

![]()

8 The sharp distinction of tone between ‘laudet’ and ‘tabescat’ helps us to see that they refer to two different feelings, laudo. meaning to call or consider someone happy, is inappropriate as an expression of competitive jealousy. It expresses admiration and congratulations for some extraordinary advantage or achievement, as Terence Heaut. 381: ‘edepol te, mea Antiphila, laudo et fortunatam iudico, id quom studuisti, isti formae ut mores consimiles forent;’ And. 96–8: ‘uno ore omnes omnia bona dicere et laudare fortunas meas, qui gnatum haberem tali ingenio praeditum.’ Or it may express good-natured envy of something which the speaker lacks and values but which he does not strive for, as Cicero, Tusc. 3. 57: ‘(potentissimus rex) qui laudat senem et fortunatum esse dicit, quod in-glorius sit…’ and 5. 115: ‘(Homerus Polyphemum) cum ariete etiam colloquentem facit eiusque laudare fortunas, quod qua vellet ingredi posset et quae vellet attingere;’ cf. Plautus, Rud. 523–4 (the speaker is soaked): o scirpe, scirpe, laudo fortunas tuas, qui semper servas gloriam aritudinis.' Thus in our poem, as at Odes 1. 1. 17, the verb resembles ![]() (both used by Maximus of Tyre, loc. cit.) or some uses of

(both used by Maximus of Tyre, loc. cit.) or some uses of ![]() e.g. Euripides, I.A. 16–19

e.g. Euripides, I.A. 16–19 ![]()

![]()

![]() translated as laudo by Cicero in Tusc. 3. 57 above.

translated as laudo by Cicero in Tusc. 3. 57 above.

9 Farmers are not always idealized as a foil to avarice; cf. Ep. 1. 7. 84–5, where Vulteius, translated to the country, ‘praeparat ulmos, immoritur studiis et amore senescit habendi.’

10 Horace frequently assumes a number of separate fundamental drives; e.g. Ep. 1. 6. 47 ff. suggests that one might try to find happiness in wealth or popularity or fine food or love; Ep. 1. 2. 55 ff. lists pleasure, envy and hatred, while Ep. 1. 1. 33 ff., after mentioning avarice and glory, goes on: ‘invidus, iracundus, iners, vinosus, amator …’ But he does share the contemporary tendency to treat avarice as the typical fault of the age; see Herter, op. cit., pp. 17–18,Google Scholar and, in connection with Horace's major theme of moderation, Solmsen, F., AJPh 68 (1947), 337 ff.Google Scholar

11 I wish to thank Dr. R. W. Hawtrey of the University of Auckland, and Professor K. H. Lee of the University of Canterbury, for comments and criticisms which have improved this essay.

- 2

- Cited by