No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

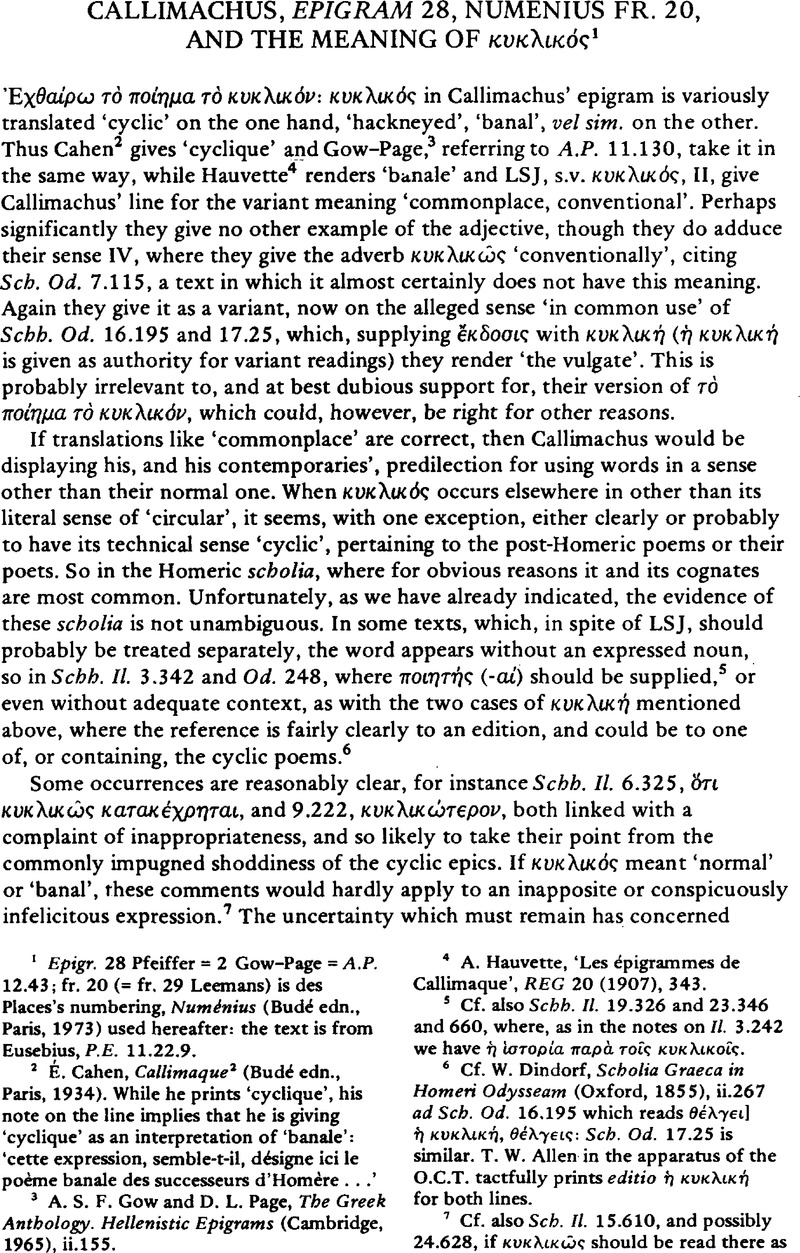

Callimachus, Epigram 28, Numenius fr. 20, and the Meaning of κυκλικός

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 11 February 2009

Abstract

- Type

- Research Article

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Classical Association 1978

References

1 Epigr. 28 Pfeiffer = 2 Gow-Page = A.P. 12.43; fr. 20 (= fr. 29 Leemans) is des Places's numbering, Numénius (Budé, edn., Paris, 1973Google Scholar) used hereafter: the text is from Eusebius, , P.E. 11.22.9.Google Scholar

2 Cahen, É., Callimaque2 (Budé, edn., Paris, 1934).Google Scholar While he prints ‘cyclique’, his note on the line implies that he is giving ‘cyclique’ as an interpretation of ‘banale’: ‘cette expression, semble-t-il, désigne ici le poéme banale des successeurs d'Homere …’.

3 Gow, A.S.F. and Page, D.L., The Greek Anthology. Hellenistic Epigrams (Cambridge, 1965), ii.155.Google Scholar

4 Hauvette, A., ‘Les épigrammes de Callimaque’, REG 20 (1907), 343.Google Scholar

5 Cf. also Schh. II. 19.326 and 23.346 and 660, where, as in the notes on II. 3.242 we have ![]() .

.

6 Cf. Dindorf, W., Scholia Graeca in Homeri Odysseam(Oxford, 1855), ii 267adSch. Od. 16.195 which reads ![]()

![]() : Sch. Od. 17.25 is similar. T. W. Allen in the apparatus of the O.C.T. tactfully prints editio

: Sch. Od. 17.25 is similar. T. W. Allen in the apparatus of the O.C.T. tactfully prints editio ![]() for both lines.Google Scholar

for both lines.Google Scholar

7 Cf. also Sch. II. 15.610, and possibly 24.628, if ![]() should be read there as proposed by Merkel, R., Apollonii Argonautia (Leipzig, 1854), p.xxxiGoogle Scholar: so too Severyns, A., Le Cycle épique dans l'école d'Aristarque. Bibl. de la Fac. de Phil, et Lett, de l'U. de Liege 40 (Liège/Paris, 1928), p.157.Google Scholar

should be read there as proposed by Merkel, R., Apollonii Argonautia (Leipzig, 1854), p.xxxiGoogle Scholar: so too Severyns, A., Le Cycle épique dans l'école d'Aristarque. Bibl. de la Fac. de Phil, et Lett, de l'U. de Liege 40 (Liège/Paris, 1928), p.157.Google Scholar

8 And others; cf. Merkel, , op. cit., pp.xxx–xxxvi.Google Scholar

9 See the discussion in Dindorf, , op. cit. 1.335Google Scholar, ad loc. More recently Severyns, , op. cit., pp.155 f.Google Scholar, takes ![]() here as clearly meaning ‘in the Cyclic style’; Wilkinson, L.P., ‘Callimachus A.P. xii. 43’Google Scholar, CR N.S. 17 (1967), 5, as meaning ‘conventionally’.Google Scholar

here as clearly meaning ‘in the Cyclic style’; Wilkinson, L.P., ‘Callimachus A.P. xii. 43’Google Scholar, CR N.S. 17 (1967), 5, as meaning ‘conventionally’.Google Scholar

10 Severyns, , op. cit., pp.155–9Google Scholar, argues that ![]() in Aristarchus' comments meant exclusively ‘à la manière des Cycliques, comme font les Cycliques’; cf. also Pfeiffer, R., History of Classical Scholarship (Oxford, 1968), p.230Google Scholar: he, however, allows at least the implication of conventionality and triviality.

in Aristarchus' comments meant exclusively ‘à la manière des Cycliques, comme font les Cycliques’; cf. also Pfeiffer, R., History of Classical Scholarship (Oxford, 1968), p.230Google Scholar: he, however, allows at least the implication of conventionality and triviality.

11 On this cf.Erbse, H., Scholia Graeca in Homeri lliadem. Scholia Vetera i (Leiden, 1969), xii f.Google Scholar Erbse excludes that scholion on II. 3.242 in which ![]() appears.

appears.

12 Erbse attributes Schh. II. 6.325a and 9.222a to Aristonicus. Severyns, loc. cit. (n. 10) discusses as Aristarchus'; Schh. II. 6.325, 15.610,24.628.

13 Dindorf, , op. cit. i, p.iii, points out that those on the later books of the Odyssey are unlikely to be early, but our examples from these are among the less clear anyhow.Google Scholar

14 Vigier ap. Mras (see n.15), Gifford, E.H., Eusebii Pampbili Praeparatio Evangelica iv (Oxford, 1903), n. ad 11.22, 544 d: Gifford suggests that the reference is to epitaphs.Google Scholar

15 Mras, K. in the G.C.S. edition (Berlin, 1956)Google Scholar, in apparatu. Given these alternatives we should clearly follow Mras, making the additional small change of ![]() . Not only does the passage suggest

. Not only does the passage suggest ![]() , but also the frequent occurence of the word in the following lines could mean that it actually stood in the text here and was simply omitted, as probably happened in line 11 (des Places's lines). But would not

, but also the frequent occurence of the word in the following lines could mean that it actually stood in the text here and was simply omitted, as probably happened in line 11 (des Places's lines). But would not ![]() , ‘the standard thing’, give the required sense anyhow?

, ‘the standard thing’, give the required sense anyhow?

16 Cf. H. Herter, ‘Kallimachos 6’, RE supp. v (1931), 430 and 451 f.Google Scholar

17 Ath. 15.669 C.

18 Cf. the index in Leemans, E.-A., Studie over den Wijsgeer Numenius van Apamea, met uitgave der fragmenten, Ac. R. de Belg. CI. des Lett. Mém. 37.2 (Brussels, 1937).Google Scholar

19 Th. 775–7 in fr. 36 (= Test. 48 Leemans), where Hesiod is named, and perhaps Op. 471 in fr. 11 (= 20 L). There may be an echo of Sophocles, O.T. fr. 25. 123 (= 2L); cf. des Places, ad loc. 10 It may possibly have been implied in the condemnation of ![]() in the Hadrianic epigram by Pollianus, , A.P. 11. 130, 1 f.Google Scholar:

in the Hadrianic epigram by Pollianus, , A.P. 11. 130, 1 f.Google Scholar: ![]()

![]() , where the primary meaning must, however, be ‘cyclic’: thus Gow-Page, , loc. cit. (n.3)Google Scholar, take this as evidence for ‘cyclic’ in Call. Epigr. 28; cf. also Severyns, , op. cit., pp.158 f.Google Scholar

, where the primary meaning must, however, be ‘cyclic’: thus Gow-Page, , loc. cit. (n.3)Google Scholar, take this as evidence for ‘cyclic’ in Call. Epigr. 28; cf. also Severyns, , op. cit., pp.158 f.Google Scholar

20 For a recent discussion of who, and what, was the target of this epigram see Klein, T.M., ‘The concept of the “Big Book’ ’, Eranos 73 (1975), 23–5: he argues that Callimachus disapproved of the cyclic poets and not of Apollonius.Google Scholar

21 Cf. now Barigazzi, A., ‘Amore e Poetica in Callimaco (ep. 28 e 6)’, RFIC 101 (1973), 186–94Google Scholar, and the references given there; but Epigr. 6 (= 55 G.-P.) on the Capture of Oechalia is not, as Barigazzi takes it to be, 193 f., evidence for Callimachus’ negative attitude to the Cycle: cf. Gow-Page, adloc.

22 Another possibility-no more-should be mentioned: since the text of Eusebius which provides the Numenius fragment is not unblemished, there could be more amiss than has been thought. So if ![]() were simply wrong-not very likely, given its rarity-there would be no clear case of its metaphorical meaning, which does not arise obviously from either the literal, or technical one, except perhaps through reflection on the unsatisfactory qualities of the cyclic poets.

were simply wrong-not very likely, given its rarity-there would be no clear case of its metaphorical meaning, which does not arise obviously from either the literal, or technical one, except perhaps through reflection on the unsatisfactory qualities of the cyclic poets.

23 I am grateful to Dr. F. T. Griffiths for discussing these matters with me, and to this journal's referee for a number of helpful suggestions, not all of which I have followed. This note was written during the tenure of a Leverhulme Research Fellowship.