Article contents

The Contest of Homer and Hesiod

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 11 February 2009

Extract

The work of many scholars in the last hundred years has helped us to understand the nature and origins of the treatise which we know for short as the Contest of Homer and Hesiod. The present state of knowledge may be summed up as follows. The work in its extant form dates from the Antonine period, but much of it was taken over bodily from an earlier source, thought to be the Movaelov of Alcidamas. Some of the verses exchanged in the contest were current even earlier, and some scholars have supposed that the story of a contest went back to the fifth, sixth, or even eighth century; but this is now much doubted.

Information

- Type

- Research Article

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Classical Association 1967

References

page 433 note 1 This, in its Greek and Latin forms, was H. Stephanus' abbreviation of the title in the archetype (Laur. 56. 1), irepi ![]()

![]() .

.

page 433 note 2 The expression ![]()

![]()

![]() (§ 3, lines 32–33 Allen) implies that Hadrian is dead, but of fresh memory.

(§ 3, lines 32–33 Allen) implies that Hadrian is dead, but of fresh memory. ![]() is Stephanus' correction of

is Stephanus' correction of ![]() . —In citing passages from the Certamen I shall use the section-numbers of Wilamowitz (Vitae Homeri et Hesiodi, 1916), which are also adopted by Colonna in his edition (Hesiodi Opera et Dies, 1959), and the linea- tion of Allen (Homeri Opera, v). Of the various twentieth-century editions, that of Rzach in his big edition of Hesiod (1902) still offers the fullest and most accurate report of the readings of the manuscript; Allen's is the most widely circulating, Wilamowitz's the most intelligent, Colonna's the most recent. That of Evelyn-White in the Loeb Hesiod (revised ed. 1936) may also be mentioned. A facsimile of the manuscript as far as § 13, line 214, is published by R. Merkelbach and H. van Thiel, Griechisches Leseheft, 1965, pp. 6–10.

. —In citing passages from the Certamen I shall use the section-numbers of Wilamowitz (Vitae Homeri et Hesiodi, 1916), which are also adopted by Colonna in his edition (Hesiodi Opera et Dies, 1959), and the linea- tion of Allen (Homeri Opera, v). Of the various twentieth-century editions, that of Rzach in his big edition of Hesiod (1902) still offers the fullest and most accurate report of the readings of the manuscript; Allen's is the most widely circulating, Wilamowitz's the most intelligent, Colonna's the most recent. That of Evelyn-White in the Loeb Hesiod (revised ed. 1936) may also be mentioned. A facsimile of the manuscript as far as § 13, line 214, is published by R. Merkelbach and H. van Thiel, Griechisches Leseheft, 1965, pp. 6–10.

page 433 note 3 Proved by the close agreement with the Flinders Petrie papyrus (now P. Lit. Lond. 191), which is dated to the third century B.C. The trivial differences of wording are not necessarily to be attributed to the Antonine compiler: I agree with Wilamowitz's judgement that ‘die Prosa so viel und wenig stimmt, wie man erwarten konnte, die Verse durchaus’ (Die Mas und Homer, p. 400).Google Scholar

page 433 note 4 Nietzsche, , Rh. Mus. xxv (1870), 536–40,Google Scholar argued so, firstly because the two verses 78–79 are quoted by Stobaeus (iv. 52. 22) as from this work, secondly because the Certamen itself (§ 14, line 240) cites it for the death of Hesiod at a point where an alternative version is given. His hypothesis received support, firstly from the Petrie papyrus, which showed that the account of the contest, at least, went back to Hellenistic times or earlier, secondly from the Michigan papyrus inv. 2754 (ii-iii A.D., ed. Winter, J. G, TAPA lvi (1925), 120 ff.), which gave the end of a narrative closely resembling the end of Cert., followed by what appeared to be an epilogue and the sub scription ![]() . But there are difficulties, which must be discussed pre sently.Google Scholar

. But there are difficulties, which must be discussed pre sently.Google Scholar

page 433 note 5 78–79 (the same two that Stobaeus attributes to Alcidamas) = Theognis 425/7 (Stobaeus quotes the Theognis lines, with their accompanying pentameters, later in the same section ![]() , iv. 52. 30); 107–8 ═ Ar. Pax 1282–3, with inessential variants.

, iv. 52. 30); 107–8 ═ Ar. Pax 1282–3, with inessential variants.

page 433 note 6 Vogt, E., Rh. Mus. cii (1959), 193–221;Google ScholarHess, K, Der Agon zwischen Homer und Hesiod, Diss. Zurich, 1960.Google Scholar

page 434 note 1 C.Q. xliv (1950), 149 ff.Google Scholar

page 434 note 2 This had been remarked by Korte, A., Arch. f. Pap. viii (1927), 263, who supposed Alcidamas to be quoting an earlier com position.Google Scholar

page 434 note 3 C.Q. N.S. ii (1952), 187 f. Körte, p. 264, had already declared himself unable to believe ‘daβ ein kultivierter Schriftsteller wie Alkidamas seine Schrift über Homer mit so stammelnden Satzen abgeschlossen habe’, and assumed shortening by the thoughtless copyist.Google Scholar

page 435 note 1 So Vogt, pp. 1998ff. The alternative, that the Antonine writer worked Homer's oracle in at the beginning of the contest, would presuppose an artistry with which the inconcinnities of his compilation are to my mind incompatible.

page 435 note 2 Nietzsche, p. 538, makes this point.

page 435 note 3 The contrast between his two personae struck Allen, Homer, The Origins and the Transmission, p. 21: ‘The austerity of Apollonius and Herodian cannot be suspected, the book is too erudite in form for a sophist … this mixture of erudition and rhetoric…’. But his suggestion that the author might be Porphyry is improbable. Porphyry dated Hesiod 100 years after Homer (Suda s.v. ![]() cf. s.v.

cf. s.v. ![]() ), an opinion which besides being incompatible with the contest story is not mentioned in the earlier sections.

), an opinion which besides being incompatible with the contest story is not mentioned in the earlier sections.

page 436 note 1 He was here arguing against Korte's theory that the account of Homer's death was a quotation in Alcidamas of an earlier work. His argument may be thought to have slightly more force against fifth-century authorship than against fourth.

page 436 note 2 Alcidamas does actually tolerate ![]()

![]() , Soph. 27.

, Soph. 27.

page 436 note 3 ‘Très probablement, cet écrit pseudo- platonicien fut composé au temps d'Aristote ou peu après.’ Souilhé, J. in the Budé Plahm, xiii (3), p. 65.Google Scholar

page 437 note 1 But the active is more normal. So Alcidamas, Soph. 30.

page 437 note 2 He also suggests ![]() . for

. for ![]()

![]() .

.

page 437 note 3 For the importance of ![]() cf. Soph. 1; Blass, , Die attische Beredsamkeit, ii 2, 47–50, 347. The argument from the honour won by Homer may be compared with Soph. 9

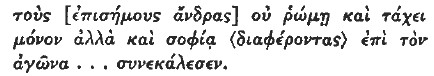

cf. Soph. 1; Blass, , Die attische Beredsamkeit, ii 2, 47–50, 347. The argument from the honour won by Homer may be compared with Soph. 9 ![]()

![]() ,Google Scholar

,Google Scholar

page 437 note 4 Page, Dodds. Alternatives ![]() and

and ![]() (Winter) do not make sense; the former does not seem to fit the traces either.

(Winter) do not make sense; the former does not seem to fit the traces either.

page 438 note 1 Alcidamas agreed with other Greeks in this matter: Soph. 18 ![]()

![]() .

.

page 438 note 2 ‘His origin and the rest of his poetry’, Page; ‘where he came from and what else he wrote’, Dodds. See the criticism by Kirk, P. 153.

page 438 note 3 This hardly needs illustration; but cf. ISOC. 12. 33 ![]()

![]()

page 438 note 4 ![]() meant, among other things, a place where books were collected. Just as later writers such as Diodorus and the mythographer Apollodorus called their books

meant, among other things, a place where books were collected. Just as later writers such as Diodorus and the mythographer Apollodorus called their books ![]() , because they gave information for which you would otherwise need a whole repository of books, Alcidamas gave the title

, because they gave information for which you would otherwise need a whole repository of books, Alcidamas gave the title ![]() to a work which covered a variety of poets. Callimachus also wrote

to a work which covered a variety of poets. Callimachus also wrote ![]() (Suda; i. xcv, ii. 339 Pf.).

(Suda; i. xcv, ii. 339 Pf.).

page 438 note 5 Homer: Heraclitus fr. 56; Hesiod: Thuc. 3. 96.

page 438 note 6 Griech. Literaturgeschichte, ii. 66.Google Scholar

page 438 note 7 Op. cit., pp. 25 ff.

page 439 note 1 Kirchhoff, A., S.B. preuss. Ak. 1892, pp. 865–91.Google Scholar

page 439 note 2 See Kirk, p. 150 n. 1.

page 439 note 3 First in Hermes xiv (1879), 161 ═ Kl. Schr. iv. 1.Google Scholar

page 439 note 4 There is more point in the fiction of a contest between Lesches and Arctinus (Phaenias ap. Clem. Strom. 1. 131. 6). They are the two main poets associated with the cyclic epics.

page 439 note 5 Alcidamas (Petrie papyrus); Philostratus, Heroic, p. 318; Tz. vit. Hes.; Apostolius 14. II (Paroem. Gr. ii. 606. 20) ![]()

![]() .

.

page 439 note 6 For the original one might conjecture ![]() , after h. Aphr. 1.

, after h. Aphr. 1.

page 440 note 1 Hes. Th. 38, shortened in 32; cf. Il. 1. 70, [Hes.] fr. 204. 113 M.-W., orac. ap. Diod. 9. 3. 2, Solon 3. 15, Eur. Hel. 14.

page 440 note 2 A similar suggestion in Bergk, , Analecta AUxandrina (1846), i. 22 n.Google Scholar

page 440 note 3 The phrase ![]() may seem to have an early ring, but is rather a poetic archaizing equivalent of

may seem to have an early ring, but is rather a poetic archaizing equivalent of ![]() as used in Cert. § 5, lines 55–56

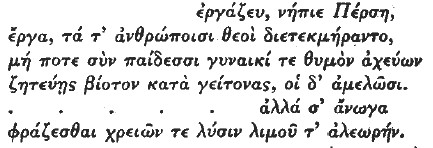

as used in Cert. § 5, lines 55–56 ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() .

.

page 441 note 1 I do not understand this. ![]() needs a verb of motion, so that 124 is a paradox; but 125 fails to account for

needs a verb of motion, so that 124 is a paradox; but 125 fails to account for ![]()

![]() (

(![]() cod.). Barnes conjectured that a line has fallen out after 124.

cod.). Barnes conjectured that a line has fallen out after 124.

page 441 note 2 So Rzach. The only alternative is Busse's division (Rk. Mus. lxiv (1909), 115 n. 1): A. 133, B. 134 ![]() , A.

, A. ![]() to 136, B. 137. But the division of the line between two speakers is surely unacceptable. The first paradox must be answered with at least one complete line.

to 136, B. 137. But the division of the line between two speakers is surely unacceptable. The first paradox must be answered with at least one complete line.

page 441 note 3 Cf.Rohde, , Kl. Schr. i. 103Google Scholar f.; Radermacher, Aristophanes' Frösche (S.B. Wien. Ak. 198/4, 1921), p. 30; Dornseiff, , Gnomon xx (1944), 139.Google Scholar

page 441 note 4 PI. Rep. 599 E, Isoc. 10. 65.

page 442 note 1 Alcidamas wrote an essay in praise of death (Cic. Tusc. 1. 116, Menander Rhet. iii. 346. 17 Sp., Tz. Chil. 11. 745 ff.), and these verses may have made a particular im pression on him.

page 442 note 2 They are of the same sort as Il. 2. 123 ff., [Hes.] fr. 304 M.–W. The irrelevant note that follows in the manuscript, ![]()

![]() ., is clearly inter polated. It is incomplete at the end, possibly because of damage to a lower margin in which it was written.

., is clearly inter polated. It is incomplete at the end, possibly because of damage to a lower margin in which it was written.

page 442 note 3 In the manuscript, the quotation ends rather abruptly at 392, with ![]()

![]() where the actual text of Hesiod proceeds

where the actual text of Hesiod proceeds ![]()

![]()

![]() . But originally the extract may have gone on to 404, since Philostratus, Heroic, p. 318 says

. But originally the extract may have gone on to 404, since Philostratus, Heroic, p. 318 says ![]()

![]()

![]() . This seems to be, not a vague account of the contents of the Works and Days, but a particular reference to the lines

. This seems to be, not a vague account of the contents of the Works and Days, but a particular reference to the lines  (397–404.)

(397–404.)

Cf. Tzetzes, , Vit. Hes., p. 49. 6 Wil. ![]()

![]() , and Nietzsche, pp. 530, 532.Google Scholar

, and Nietzsche, pp. 530, 532.Google Scholar

page 443 note 1 For this criterion of art cf. Ar. Ran. 1420ff., Alcid. Soph. 9, 26, 27, Isoc. 2. 43.

page 443 note 2 Rh. Mus. cii (1959), pp. 199, 201, al.Google Scholar

page 443 note 3 So already Nietzsche, 539 f.

page 443 note 4 There is in Lucian (Vera hist. 2. 22), Philostratus, and Apostolius, but that is not relevant. To ignore the original point of the story would be typical of the Second Sophis tic. The phrase recorded by Apostolius is probably drawn from a writer of that period, though not from the Philostratus passage as some have thought.

page 443 note 5 Apophth. Lac. 223A; cf. Ael. VH 13. 19.

page 443 note 6 Cf. Busse, p. 119; Dornseiff, p. 137. The ![]() , mentioned more than once by Aristotle, seems to have been among Alcidamas' most important works.

, mentioned more than once by Aristotle, seems to have been among Alcidamas' most important works.

page 444 note 1 ![]() is particularly used of Homer: Cert., lines 214, 309, 338, Ar. Ran. 1033, [Plut.] Cons. Apoll. 104 D, Tz. Exeg. in Il., p. 7. 26, etc.

is particularly used of Homer: Cert., lines 214, 309, 338, Ar. Ran. 1033, [Plut.] Cons. Apoll. 104 D, Tz. Exeg. in Il., p. 7. 26, etc.

page 444 note 2 Cf. also [Plut.] Vita I, Eust. in Horn., p. 4. 18.

page 444 note 3 Veil. I. 5. 3 quern si quis caecum genitum putat, omnibus sensibus orbus est ˜ Procl. lines 47–49 (cf. also Luc. Vera hist. 2. 20); Veil. ibid, hic longius a temporibus belli quod composuit Troici quam quidam rentur abfuit, nam ferme ante annos DCCCCL floruit, intra mille natus est ˜ Procl. lines 59–63; Veil. 1. 7. 1 hums temporibus aequalis Hesiodus fiiit, circa CXX annos distinctus ab Homeri aetate ˜ Procl. lines 50–57. Velleius' chronological framework comes from Apollodorus via Nepos: Jacoby, Apollodors Chronik, pp. 101 ff.; Dihle, RE viiiA 642 f. Cf. Rohde, , Rh. Mus. xxxvi (1881), 551–2 ═ Kl. Schr. i. 87–88.Google Scholar

page 445 note 1 The Smyrnaeans' story that Homer was so named after he became blind comes from Ephorus (70 F 1), who made Homer of Cymaean stock but born in Smyrna. The Chian claim based on the Chian Homeridae may have come in Hellanicus (4 F 20); though the Roman Life, p. 30. 24 Wil., does not name him among the authorities for Homer's Chian origin, it names Damastes (5 F 11), Anaximenes (72 F 30), Pindar (fr. 264), and Theocritus ![]() (

(![]() cf. Idyll 7. 47). The Colo-phonian claim was made by the Colc-phonians Antimachus and Nicander.

cf. Idyll 7. 47). The Colo-phonian claim was made by the Colc-phonians Antimachus and Nicander.

page 445 note 2 Alcidamas is not likely. He referred somewhere to Homer's not being a Chian (Arist. Rhet. I398b12), and the oracle given to Homer before the contest makes Ios the homeland of his mother.

page 445 note 3 Proclus cites it, but in an earlier section of his Life, from a different source.

page 446 note 1 Set out conveniently by Allen, op. cit., facing p. 32. Cf. Rohde, , Rh. Mus. xxxvi (1881), 385 ff. ═ Kl. Schr. i. 6ff.Google Scholar

page 446 note 2 On the way he reveals some ideas of his own about the poets' parentage which are inconsistent with the information in §§ 1–4. Hesiod is son of Dios (156), as in the Epho-rus-Charax stemma, but Homer is son of Meles (75, 151) and a mother who comes from Ios (59).

page 447 note 1 He had done the Margites before the contest, line 55. In line 260, the words ![]()

![]() are evi dently interpolated; they cannot have been written by a man who has just stated as a fact that Homer did recite these among his poems.

are evi dently interpolated; they cannot have been written by a man who has just stated as a fact that Homer did recite these among his poems.

page 447 note 2 In the Herodotean Life and the Suda, this is composed at Samos.

page 447 note 3 The explanation of this uneventful visit seems to be as follows. Aristarchus was troubled by Homer's use of ![]() besides the ‘older’ name

besides the ‘older’ name ![]() ), and found it neces sary to explain to his students that Homer used it

), and found it neces sary to explain to his students that Homer used it ![]() , speaking in his own person (sch.^ Il. 2. 570, cf. 6. 152, 210, 13. 301). Even Velleius thinks this worth saying, 1. 3. 3. Homer is therefore made to visit Corinth, in this account, simply to make sure that he is acquainted with the place.

, speaking in his own person (sch.^ Il. 2. 570, cf. 6. 152, 210, 13. 301). Even Velleius thinks this worth saying, 1. 3. 3. Homer is therefore made to visit Corinth, in this account, simply to make sure that he is acquainted with the place.

page 447 note 4 Homer's celebration of ![]() attracted attention early. Cleisthenes of Sicyon banned the recitation of Homer in Sicyon because of it (Hdt. 5. 67. 1). In the Herodotean Life § 28, line 378 Allen, before Homer sets sail from Ionia for the mainland, he notices that he has eulogized Argos frequently but not Athens, and therefore inserts a few passages in praise of Athens. Philochorus actually made Homer an Argive (328 F 209), probably because of the Argive references (Jacoby ad 16c.).

attracted attention early. Cleisthenes of Sicyon banned the recitation of Homer in Sicyon because of it (Hdt. 5. 67. 1). In the Herodotean Life § 28, line 378 Allen, before Homer sets sail from Ionia for the mainland, he notices that he has eulogized Argos frequently but not Athens, and therefore inserts a few passages in praise of Athens. Philochorus actually made Homer an Argive (328 F 209), probably because of the Argive references (Jacoby ad 16c.).

page 448 note 1 Above, p. 445 n. 2.

page 448 note 2 The statement that it was foisted on him by Cynaethus (sch. Pind. Nem. 2. 1) may have originated from this or a related source.

page 448 note 3 Unless it insisted that Homer was bor in Chios—the genealogy implies birth at Smyrna.

page 450 note 1 I will mention only two places where a conjecture may be a positive improvement: § 14, line 228 ![]()

![]()

- 19

- Cited by