No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 11 February 2009

None of the emendations proposed so far (cf. Ludwich's apparatus) is satisfactory. As Keydell (cf. his apparatus) reminds us, Ap. Rhod. I. 1205 makes Nonnus'  untouchable, and thereby disposes of all the conjectures which would alter these words; consequently, the corruption must be hiding in the impossible

untouchable, and thereby disposes of all the conjectures which would alter these words; consequently, the corruption must be hiding in the impossible  .

.

page 63 note 2 It is also to be noted that ![]() is the formula used by Nonnus in his similes, in correspondence to

is the formula used by Nonnus in his similes, in correspondence to ![]() : cf., e.g., 1. 310–19, 2. 11–18, 20. 333–41, 22. 171–8. The formal aspects of Nonnus' similes are treated by Wild, G., Die Vergleiche bei Nonnus (Prgr. Regensburg, 1886), pp. 81 f.Google Scholar

: cf., e.g., 1. 310–19, 2. 11–18, 20. 333–41, 22. 171–8. The formal aspects of Nonnus' similes are treated by Wild, G., Die Vergleiche bei Nonnus (Prgr. Regensburg, 1886), pp. 81 f.Google Scholar

page 63 note 3 We should, however, rather expect ![]() to appear in two subsequent lines, like, e.g., 3. 313–14: cf. Koechly's own suggestion, in his Commentarius criticus, ad loc. On Nonnus' iterations cf. Schiller, F., De Iteratione Nonniana (Diss. Breslau, 1909)Google Scholar, and now Keydell, R., ‘Wortwiederholung bei Nonnos’, Byz. Zeitschr. xlvi (1953), 1 ff.Google Scholar

to appear in two subsequent lines, like, e.g., 3. 313–14: cf. Koechly's own suggestion, in his Commentarius criticus, ad loc. On Nonnus' iterations cf. Schiller, F., De Iteratione Nonniana (Diss. Breslau, 1909)Google Scholar, and now Keydell, R., ‘Wortwiederholung bei Nonnos’, Byz. Zeitschr. xlvi (1953), 1 ff.Google Scholar

page 63 note 4 Thanks in particular to Keydell's labours, it is now clear that Nonnus' poem, which the author wrote ‘rasch und leichtfertig’ (Keydell, , R.E. s.v. Nonnos, col. 910)Google Scholar, which is in parts merely a ‘Konglomerat von Bruchstiicken’ (Keydell, Burs. Jahresber. ccxxx. 104)Google Scholar and which was left without the finishing touches and published posthumously (as every peruser of Keydell's apparatus can now easily see: cf., e.g., n. 431 or 29. 278 for the posthumous publication, and 11. 406 ff. for a specimen of 'narratio incohata et incondita') contains numerous Altemativfassungen: cf, for example, Keydell's apparatus on 8. 61–77, 22. 320–53, 384 ff., 23. 139–41, 233 a, 25. 308, 26. 151, 36. 104–5. What seems to have remained unnoticed is that such Altemativfassungen are not confined to couples of lines or groups of lines, but are also present, in the form of hemistichs, within one line, which is entirely natural, if we consider the poet's Arbeitsweise and the essentially formulaic nature of his language. Nothing would be easier than to emend, by drawing from Nonnus himself metrically suitable alternatives, lines such as 5. 308, 8. 286, or 12. 364: such duplicate expressions of the same idea jotted down by Nonnus, which the author would have eliminated if he had been able to give a final revision to his work, should be left alone by anybody other than the poet. In such lines, the first hemistich represents a pentimento replaced by the second one, but not yet corrected by the author, precisely as, in the case of alternative lines, both Altemativfassungen were left coexisting by the writer. For instance, Nonnus started 8. 286 with ![]() …

… ![]() but elected to end the line with the same formula as in 19. I, which procedure implies the removal of

but elected to end the line with the same formula as in 19. I, which procedure implies the removal of ![]() (by

(by ![]() , cf. 8. 69?

, cf. 8. 69? ![]() ?

? ![]() ?: cf. Koechly and Ludwich, ad loc.: any of these perfectly Nonnian alternatives would do, but only Nonnus should be allowed the choice, not the modern textual critics!). Methodologically fundamental Pasquali, , St. Tradiz.2, pp. 401 ff.Google Scholar

?: cf. Koechly and Ludwich, ad loc.: any of these perfectly Nonnian alternatives would do, but only Nonnus should be allowed the choice, not the modern textual critics!). Methodologically fundamental Pasquali, , St. Tradiz.2, pp. 401 ff.Google Scholar

page 64 note 1 Rouse translates ‘while the bull stretched’, but the stretching metaphor is taken by Nonnus from Homer's ![]() i.e. implies the idea of bending: cf. line 52,

i.e. implies the idea of bending: cf. line 52, ![]() ‘bending his back, which was previously unbent’ (like a loosened bow, cf. Homer's

‘bending his back, which was previously unbent’ (like a loosened bow, cf. Homer's ![]() ). Very clear is, in this respect, 5. 150f.

). Very clear is, in this respect, 5. 150f.

page 64 note 2 Nonnus' simile was, in all probability, inspired by Moschus, , Eur. 119Google Scholar (+ 117 ![]() 125.

125.

page 64 note 3 For this reason ![]() which I wanted to restore, referring

which I wanted to restore, referring ![]() to the bull's lifted tail, is impossible. It is true that, when bulls swim, their tails, normally hanging downwards, vertically, move upwards and remain horizontal, stretched out in their erected position on the surface of the water; it is true that Nonnus was fond of describing outstretched tails (cf. 42. 190 ff., where a

to the bull's lifted tail, is impossible. It is true that, when bulls swim, their tails, normally hanging downwards, vertically, move upwards and remain horizontal, stretched out in their erected position on the surface of the water; it is true that Nonnus was fond of describing outstretched tails (cf. 42. 190 ff., where a ![]() ‘lifts the tail straight over his back’ [Rouse], 23. 206 f., where a

‘lifts the tail straight over his back’ [Rouse], 23. 206 f., where a ![]() ; cf. also 5. 185, 10. 168, 270 [where

; cf. also 5. 185, 10. 168, 270 [where ![]() probably means, as an epitheton ornans, ‘(previously) erected’, cf. De Marcellus' rendering ‘au lieu de se dresser’], 14. 178, 28. 226); it is true that Nonnus was fond of the formula

probably means, as an epitheton ornans, ‘(previously) erected’, cf. De Marcellus' rendering ‘au lieu de se dresser’], 14. 178, 28. 226); it is true that Nonnus was fond of the formula ![]() (cf. 7. 353, 8. 376, 9. 207, 13. 126, 256, 19. 318): but, apart from the fact that, as has just been observed, aeipe in the line which we are examining must mean ‘carried’, it is to be noted that, in the formula

(cf. 7. 353, 8. 376, 9. 207, 13. 126, 256, 19. 318): but, apart from the fact that, as has just been observed, aeipe in the line which we are examining must mean ‘carried’, it is to be noted that, in the formula ![]() , the adjective

, the adjective ![]() is always accompanied by a substantive (

is always accompanied by a substantive (![]() ; cf. for variant formulae, 17. III, 19, 274, 20. 401, 22. 73, 24. 299, where the adjective is accompanied by a noun; cf. also 1. 384, 11. 57, 20. 51), whereas in 1. 79 one would have to supply

; cf. for variant formulae, 17. III, 19, 274, 20. 401, 22. 73, 24. 299, where the adjective is accompanied by a noun; cf. also 1. 384, 11. 57, 20. 51), whereas in 1. 79 one would have to supply ![]() from the preceding line, which proceeding would be unusual and strained, as has been pointed out to me.

from the preceding line, which proceeding would be unusual and strained, as has been pointed out to me.

page 64 note 4 Cf. also 53, ![]() (where Nonnus, to avoid any ambiguity, uses the compound

(where Nonnus, to avoid any ambiguity, uses the compound ![]() to express the notion of lifting).

to express the notion of lifting).

page 65 note 1 The ![]() being a freight-ship, one would be tempted to emend

being a freight-ship, one would be tempted to emend ![]() = cargo: but this meaning is only attested in Dem. 32. 2 (cf. L.S.J., s.v.

= cargo: but this meaning is only attested in Dem. 32. 2 (cf. L.S.J., s.v. ![]() , II) and it is unlikely that Nonnus might have revived it: in his own times, as we can see from Preisigke, Wörterb. iii, Abschn. II, s.v.

, II) and it is unlikely that Nonnus might have revived it: in his own times, as we can see from Preisigke, Wörterb. iii, Abschn. II, s.v. ![]() , the word only meant fare, passage-money. There are no certain attestations of

, the word only meant fare, passage-money. There are no certain attestations of ![]() in Epic: Hermann conjectured

in Epic: Hermann conjectured ![]()

![]() in Orph. Arg. 1139 = 1144, but his emendation, accepted by Abel, is rejected by Dottin, who maintains the manuscript reading

in Orph. Arg. 1139 = 1144, but his emendation, accepted by Abel, is rejected by Dottin, who maintains the manuscript reading ![]() .

.

page 65 note 2 The motif ![]() in line 79 is a direct echo of

in line 79 is a direct echo of ![]() in line 66. In the formula

in line 66. In the formula ![]() ‘orationem continuat’ (cf. Ebeling, , Lex. Homer.Google Scholar, s.v.

‘orationem continuat’ (cf. Ebeling, , Lex. Homer.Google Scholar, s.v. ![]() p. 248): in other words,

p. 248): in other words, ![]() means ‘that, the above-mentioned Sidonia.n

means ‘that, the above-mentioned Sidonia.n ![]() ' (mentioned in line 66), and resumes the narration interrupted by

' (mentioned in line 66), and resumes the narration interrupted by ![]() in line 72; the object to

in line 72; the object to ![]() i.e. ‘her’, is easily understood in so far as made obvious by the context to which the

i.e. ‘her’, is easily understood in so far as made obvious by the context to which the ![]() 63,

63, ![]() 66). The omission of the pronominal accusative of the 3rd person (in this case

66). The omission of the pronominal accusative of the 3rd person (in this case ![]() is meant to be a Homerism, , cf. in particular Krüger, Griech. Sprachl. ii. 23 (Berlin, 1871)Google Scholar, § 61. 7, Anm. 1 (= p. 134): ‘sehr ausgedehnt ist … bei Homer die Ergänzung eines obliquen Casus des persön-lichen Pronomens, besonders der dritten Person.’ The best treatment of this point is in Naegelsbach, Anmerkungen zur Ilias, nebst Excursen … (Nürnberg, 1834 1), pp. 311 ff.Google Scholar (= Excurs xviii). The object of

is meant to be a Homerism, , cf. in particular Krüger, Griech. Sprachl. ii. 23 (Berlin, 1871)Google Scholar, § 61. 7, Anm. 1 (= p. 134): ‘sehr ausgedehnt ist … bei Homer die Ergänzung eines obliquen Casus des persön-lichen Pronomens, besonders der dritten Person.’ The best treatment of this point is in Naegelsbach, Anmerkungen zur Ilias, nebst Excursen … (Nürnberg, 1834 1), pp. 311 ff.Google Scholar (= Excurs xviii). The object of ![]() is as clear as, for example, the object of

is as clear as, for example, the object of ![]() and

and ![]() in Il. 18. 350 ff.

in Il. 18. 350 ff.

page 65 note 3 On the suprascript semicircle = os cf. Allen, , Notes on Abbrev., pp. 20 f.Google Scholar, with Plate VI. An even better palaeographical explanation is suggested to me by Prof. Dover: the suprascript circle, usually em ployed to denote ov, was sometimes used to denote ov, cf. Bast, Comm. Pal., pp. 770 ff.Google Scholar

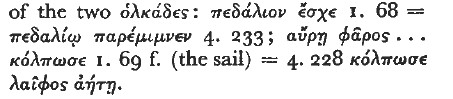

page 65 note 4 The Phoenician ![]() is a merchant-vessel, an

is a merchant-vessel, an ![]() : Europa's brother, Cadmos, evidently used such a type of

: Europa's brother, Cadmos, evidently used such a type of ![]() (cf. 4. 226 ff., esp. 242,

(cf. 4. 226 ff., esp. 242, ![]() .

.

page 65 note 5 Cf. also Epich., fr. 54 Kaib. ![]()

![]() Nonnus' epithet

Nonnus' epithet ![]() (1. 46) is, in all probability, directly inspired by Callimachus'

(1. 46) is, in all probability, directly inspired by Callimachus' ![]() . In conclusion: having already said that the bull came from Sidon (1. 46) and that he was an

. In conclusion: having already said that the bull came from Sidon (1. 46) and that he was an ![]() (1. 66), and the reader having been thus prepared, Nonnus calls the bull

(1. 66), and the reader having been thus prepared, Nonnus calls the bull ![]() , which was a

, which was a ![]() (4. 242). Noteworthy are the corresponding descriptive features

(4. 242). Noteworthy are the corresponding descriptive features  .

.

page 66 note 1 The motif is the same as, e.g., at 5. 609 f.: ![]()

page 67 note 1 We have already noted the formula ![]() cf. 6. 189 (the tooth is, of course, a metaphorical one). Nonnus' formula

cf. 6. 189 (the tooth is, of course, a metaphorical one). Nonnus' formula ![]() was obviously inspired by Ap. Rh. Arg. 4. 1606.

was obviously inspired by Ap. Rh. Arg. 4. 1606.

page 67 note 2 The adjective ![]() hairy, occurs in Nonnus, e.g. 6. 160.

hairy, occurs in Nonnus, e.g. 6. 160.

page 67 note 3 The opposite process was perhaps fol lowed by Nonnus when coining the name ![]() (from the adjective

(from the adjective ![]() ). I had at first thought of the adjectival form

). I had at first thought of the adjectival form ![]() as being derived from the Homeric personal name

as being derived from the Homeric personal name ![]() but the derivation would be made more complicated by the difference in declension, as Prof. Dover rightly objected to me.

but the derivation would be made more complicated by the difference in declension, as Prof. Dover rightly objected to me.

page 67 note 4 Cf. Keydell's, Praefatio to his edition, p. 37: ‘Versus spondiaci qui dicuntur, apud N. non reperiuntur.’Google Scholar

page 68 note 1 Changed to ![]() by Koechly, but unnecessarily: for such metaphors, not limited to weapons, cf., e.g.,

by Koechly, but unnecessarily: for such metaphors, not limited to weapons, cf., e.g., ![]() 28. 298,

28. 298, ![]() 21. 90,

21. 90, ![]() 21. 41.

21. 41.

page 68 note 2 Or ![]() ; on the reading in the archetypus cf. Keydell's apparatus.

; on the reading in the archetypus cf. Keydell's apparatus.

page 68 note 3 Cf., e.g., 5. 27. At 7. 194 (![]() …

… ![]() ) the epithet

) the epithet ![]() refers to the arrow decked, covered with ivy (cf. 7. 132). For other attestations of the adjective in Nonnus cf., e.g., 8. 9, 17. 20, 38. 174.

refers to the arrow decked, covered with ivy (cf. 7. 132). For other attestations of the adjective in Nonnus cf., e.g., 8. 9, 17. 20, 38. 174.

page 68 note 4 For one moment we are tempted to save ![]() in our emendation, because of the possibility of an etymological allusion made by Nonnus to

in our emendation, because of the possibility of an etymological allusion made by Nonnus to ![]() But the expected etymology (Nonnus is exceedingly fond of them) is already given in line 38 (

But the expected etymology (Nonnus is exceedingly fond of them) is already given in line 38 (![]()

![]() line 56); besides, the sense would not justify the absence of a- (‘dissoluble’ is clearly not required by the context), and

line 56); besides, the sense would not justify the absence of a- (‘dissoluble’ is clearly not required by the context), and ![]() would not scan. Cf. Ludwich's apparatus.

would not scan. Cf. Ludwich's apparatus.

page 68 note 5 Critica, Silva, Pars Quarta (Cambridge, 1793). pp. 47 ff.Google Scholar

page 68 note 1 In 36. 360 ff. the ![]() -metaphor is, of course, limited to line 365: the plant elsewhere described as enveloping

-metaphor is, of course, limited to line 365: the plant elsewhere described as enveloping ![]()

![]() including, obviously, his throat (line 375).

including, obviously, his throat (line 375).

page 69 note 2 Cf. also lines 59 ![]() and 60

and 60 ![]() .

.

page 69 note 3 This is an almost invariably fatal objection to a conjecture.

page 69 note 4 In the type ![]()

![]() ) the component

) the component ![]() has the value indicated in L.S.J., s.v.

has the value indicated in L.S.J., s.v. ![]() V. 7, and the second component denotes the material out of which something is made (this could hardly apply to

V. 7, and the second component denotes the material out of which something is made (this could hardly apply to ![]() ); these compounds are, in any case, adjectival, as are those compounds are, in any case, adjectival, as are those of the type

); these compounds are, in any case, adjectival, as are those compounds are, in any case, adjectival, as are those of the type ![]()

![]() .

.

page 69 note 5 This type (cf. ![]() ‘very digger’ L.S.J.; excellently translated by Benner and Forbes ‘a regular trench-digger’) seems to have become fairly popular in later prose (e.g.

‘very digger’ L.S.J.; excellently translated by Benner and Forbes ‘a regular trench-digger’) seems to have become fairly popular in later prose (e.g. ![]() ) probably owing to the influence of philosophical language (cf., e.g.,

) probably owing to the influence of philosophical language (cf., e.g., ![]() .

.

page 69 note 6 The component ![]() was introduced into epic by an author well known to Nonnus, Apollonius Rhodius (on

was introduced into epic by an author well known to Nonnus, Apollonius Rhodius (on ![]() cf. Boesch, , De Ap. Rh. Elocut. [Diss. Berlin, 1908], pp. 61 f.).Google Scholar

cf. Boesch, , De Ap. Rh. Elocut. [Diss. Berlin, 1908], pp. 61 f.).Google Scholar

page 69 note 7 This explanation, however, would be contradicted by lines 37–38 ![]() ; cf., on the other hand, 15. 133 ff.

; cf., on the other hand, 15. 133 ff.

page 69 note 8 Cf, e.g., for such threats or wishes (it all depends on who is uttering them), 33. 253 f., 36. 466 ff.

page 70 note 1 The ligature MO (= μo), which could be confused with TO, cannot be of any help in our case, because it is only found in early papyri (second century B.C.).

page 70 note 2 Similarly, at 33. 276 I emended the corrupt Xvaiv into SeW, only to learn from Ludwich's apparatus that the conjecture had already been made by De Marcellus. The latter's emendation, as is now necessary to stress on account of Keydell's disregard of it, is palmary: the poet means that the snake ‘tied’ (i.e. put round) its tail to its own head; the image—and wording— is the same as in 6. 195, where a snake ‘encircled’ Titan's ‘neck in snaky spiral coils’ (Rouse), ![]()

![]() ; cf. also 14. 363, 15. 83 f. On

; cf. also 14. 363, 15. 83 f. On ![]() governing the dative in Nonnus cf. Keydell's, Prolegomena, p. 59.Google Scholar

governing the dative in Nonnus cf. Keydell's, Prolegomena, p. 59.Google Scholar

page 70 note 3 Cf., on the other hand, ![]() … = to learn that…, e.g. 5. 513, 35. 191, 36. 444. At 24. 178

… = to learn that…, e.g. 5. 513, 35. 191, 36. 444. At 24. 178 ![]() refers to the revelling noise made by the victorious army, as is evident from line 143.

refers to the revelling noise made by the victorious army, as is evident from line 143.

page 70 note 4 Cf. Ebeling, , Lex. Homer.Google Scholar, s.v. ![]() and Wecklein, , ‘Uber Zenodot und Aristarch’, in Sitzungsber. d. Bayer. Akad. d. Wiss., Philos.-phUol. Kl., Jahrg. 1919, Abh. 7, p. 35.Google Scholar For

and Wecklein, , ‘Uber Zenodot und Aristarch’, in Sitzungsber. d. Bayer. Akad. d. Wiss., Philos.-phUol. Kl., Jahrg. 1919, Abh. 7, p. 35.Google Scholar For ![]() = step in Nonnus cf., e.g., 2. 693, 3. 54.

= step in Nonnus cf., e.g., 2. 693, 3. 54. ![]() = step in Metab, . 8. 36.Google Scholar

= step in Metab, . 8. 36.Google Scholar

page 71 note 1 The sedes of ![]() , in 21. 286, is the same as in 42. 227.

, in 21. 286, is the same as in 42. 227.

page 71 note 2 Cf. ![]() both. often used by Nonnus.

both. often used by Nonnus.

page 71 note 3 In Metab. 19. 73 ![]() …

… ![]() the adjective describes those

the adjective describes those ![]() which have a very large iron head.

which have a very large iron head.

page 72 note 1 The image ![]() (paralleled by

(paralleled by ![]() ) is complete by the epithet

) is complete by the epithet ![]() which means her trailing, revolving, as in Nic. Ther. 160 (the metaphor is of course taken from the snake's completed

which means her trailing, revolving, as in Nic. Ther. 160 (the metaphor is of course taken from the snake's completed ![]() tail: cf. Ital. serpeggiante, German here schlängelnd, of a path). Cf., for this meaning the of the adjective, 44. 110.

tail: cf. Ital. serpeggiante, German here schlängelnd, of a path). Cf., for this meaning the of the adjective, 44. 110.

page 73 note 1 As ![]()

![]() ) the girl is visualized not only as white-skinned, but also tall. ‘Eine hohe Gestalt hat ihnen (sc. the Greeks) immer als Vorzug gegolten, und war namentlich ein wesentlicher Teil ihres weiblichen Schön-heitsideals’ (Beloch, Griech. Gesch. i2. I, p. 94). Cf., e.g., Hor. Sat. I. 2. 123 f.Google Scholar, Max. Tyr. 24. 18. 7

) the girl is visualized not only as white-skinned, but also tall. ‘Eine hohe Gestalt hat ihnen (sc. the Greeks) immer als Vorzug gegolten, und war namentlich ein wesentlicher Teil ihres weiblichen Schön-heitsideals’ (Beloch, Griech. Gesch. i2. I, p. 94). Cf., e.g., Hor. Sat. I. 2. 123 f.Google Scholar, Max. Tyr. 24. 18. 7 ![]() (sc. Sappho), Schol. Luc. Im. 18.

(sc. Sappho), Schol. Luc. Im. 18. ![]()

![]() (sc. Sappho); cf. in particular A.P. 5. 121. 1; also 5. 76. 2

(sc. Sappho); cf. in particular A.P. 5. 121. 1; also 5. 76. 2 ![]() .

.

page 73 note 2 At 28. 59 ![]() refers to the kind of shield which was ‘oblongum’ (cf. Ebeling, , Lex. Homer., s.v.

refers to the kind of shield which was ‘oblongum’ (cf. Ebeling, , Lex. Homer., s.v. ![]() ).Google Scholar

).Google Scholar

page 73 note 3 On ancient cosmetic methods cf. in particular Böttiger, , Sabina (Leipzig, 1806 2)Google Scholar, and Blumner, , Die röm. Privataltert., (Mün-chen, 1911), pp. 435 ff.Google Scholar In Tert. Cult. fem. I. 2. ilium ipsum nigrum pulverem, quo oculorum exordia produamtur, the author refers to the practice of lengthening the eyes at their comers (very much as ladies do today) and not to the lengthening of the eyebrows, as Blümner, (op. cit., p. 437, note 12Google Scholar) thinks (cf. also the T.L.L., s.v. exordium, 1566. 11 ff.). On ‘das Umziehen der Lider längs der Wimpern mit einer Schwärze, wodurch die Augen gröβer erscheinen sollen’ (a practice which stresses the almond-shaped form of the human eye) cf. in particular Friedländer on Juvenal 2. 94, with his usual impeccable accuracy. Böttiger, , op. cit. i. 28Google Scholar, very appropriately notes that the ![]() has transformed Sabina into ‘eine farrenäugige Juno, um mit Vater Homer zu sprechen’ (italics mine). The epic poet Nonnus has precisely Vater Homer in mind, together with contemporary toiletry. On the

has transformed Sabina into ‘eine farrenäugige Juno, um mit Vater Homer zu sprechen’ (italics mine). The epic poet Nonnus has precisely Vater Homer in mind, together with contemporary toiletry. On the ![]() cf. in particular Thes., s.v.

cf. in particular Thes., s.v. ![]() 309 B, with still useful bibliography.

309 B, with still useful bibliography. ![]() may be taken to mean either ‘underline, stress, emphasize’, or ‘delineate’ (cf. Passow6, s.v., 3 b ‘eine Contour machen’): whichever meaning we prefer, however, the result of the

may be taken to mean either ‘underline, stress, emphasize’, or ‘delineate’ (cf. Passow6, s.v., 3 b ‘eine Contour machen’): whichever meaning we prefer, however, the result of the ![]() is the same, i.e. the eyes are made not more round, but more almond-shaped. Gf. Triller(us), , D. W., Observ. Crit. (Frankfurt, 1742), p. 400Google Scholar: for cosmetic purposes, the stibium was used by ladies ‘ad palpebras denigrandas [that is, to delineate their contour] earumque fines [i.e. ends] latius pro-ferendos’. Fr. Junius, in his commentary on Tertullian, , loc. cit. (Franeker, 1598, p. 112)Google Scholar, proposed exodia for exordia, but his conjecture is unnecessary: exordia here means ‘le début’, i.e. ‘le bord, le contour des yeux’ (cf. Blaise, , Diet. Aut. Chrét., s.v. exordium)Google Scholar: it is obvious that such almond-shaped contours producuntur, can be lengthened, at the sides (i.e. at the corners of the eyes) just as the effeminate producit, lengthens his supercilium obviously at its ends in Juvenal 2. 93 f.

is the same, i.e. the eyes are made not more round, but more almond-shaped. Gf. Triller(us), , D. W., Observ. Crit. (Frankfurt, 1742), p. 400Google Scholar: for cosmetic purposes, the stibium was used by ladies ‘ad palpebras denigrandas [that is, to delineate their contour] earumque fines [i.e. ends] latius pro-ferendos’. Fr. Junius, in his commentary on Tertullian, , loc. cit. (Franeker, 1598, p. 112)Google Scholar, proposed exodia for exordia, but his conjecture is unnecessary: exordia here means ‘le début’, i.e. ‘le bord, le contour des yeux’ (cf. Blaise, , Diet. Aut. Chrét., s.v. exordium)Google Scholar: it is obvious that such almond-shaped contours producuntur, can be lengthened, at the sides (i.e. at the corners of the eyes) just as the effeminate producit, lengthens his supercilium obviously at its ends in Juvenal 2. 93 f.

page 74 note 1 The same love for descriptive precision appears in Mitab, . 21. 63 f., where the ![]() generally long-shaped.Google Scholar

generally long-shaped.Google Scholar

page 74 note 2 A critic who knew well what meaning ravu- has in Greek compounds (including those used or coined by Nonnus), Koechly, wanted to emend ![]()

![]() ; other critics, who rightly leave the reading

; other critics, who rightly leave the reading ![]() unchanged, translate the word, however, inaccurately (‘weitäugig, grossäugig', Passow5; ‘large-eyed, full-eyed’, L.S.J.; ‘a glaring bull’ is Rouse's rendering of Nonnus' passage). Nonnus'

unchanged, translate the word, however, inaccurately (‘weitäugig, grossäugig', Passow5; ‘large-eyed, full-eyed’, L.S.J.; ‘a glaring bull’ is Rouse's rendering of Nonnus' passage). Nonnus' ![]() was perhaps inspired by

was perhaps inspired by ![]() in which compound

in which compound ![]() expresses the idea of the eyes being broadened at their corners, i.e. their almond-shaped contour being lengthened.

expresses the idea of the eyes being broadened at their corners, i.e. their almond-shaped contour being lengthened.