The review of an interesting group of inscriptions on Samian wareFootnote 1 from the ancient mansio of Belsinon (Mallén, Zaragoza), situated in the Middle Ebro Valley, in the interior of Hispania Tarraconensis,Footnote 2 has made it possible to document a sequence that seems to belong to one of the monostichs included in the Carmina XII sapientum, a collection of ludic poems perhaps assembled during the fourth century c.e. or a little earlier and included in modern times in the so-called Anthologia Latina.Footnote 3 It has recently been identified by A. Friedrich as the first work by the Christian author Lactantius (c.240‒320 c.e.) mentioned in Jerome's catalogue.Footnote 4

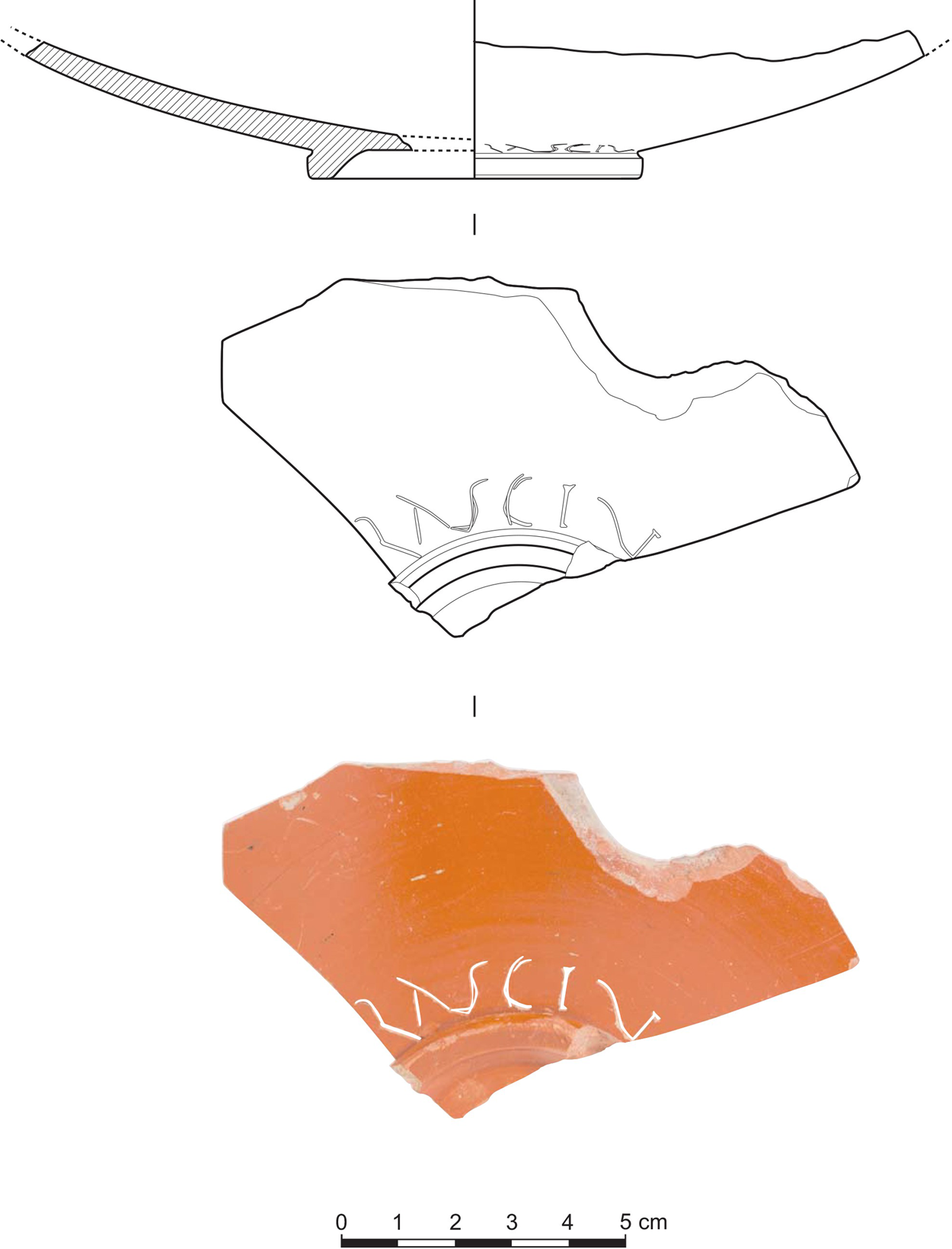

The inscription was produced post cocturam on a bowl of Spanish Samian ware, form Ritterling 8. Only a fragment is preserved, which measures 6.3 x 11 cm. It was recovered around 1920. It is currently deposited in Zaragoza Museum (NIG 34644). It can be dated to the turn of the first and second centuries c.e.

Fig. 1: Bowl of Spanish Samian ware, with inscription.

The inscription runs around the base, on the exterior of the vase. The letters show actuarial features and serifs. The A has been written with two diagonal strokes, as is typical in Old Roman Cursive.Footnote 5 They measure c.1 cm. Its reading does not present problems, despite the first letter being incomplete:

[---]RASCIV[---]

The sequence, in scriptio continua, but with a slightly larger space between the fifth and the sixth letters, seems to belong to the hexameter:

It is not possible to confirm whether the original text corresponded with the whole hexameter or perhaps only with the first part, owing to the limited space available.

The verse, composed of six words of six letters, is associated with the popular game of chance, duodecim scripta, considered an antecedent of modern backgammon, of which we know many tabulae lusoriae.Footnote 6 Some of these include short poems such as the one studied here.Footnote 7 It was recorded in the first section of the above-mentioned Carmina alongside other hexameters also related to this game (Anth. Lat. 495–506).Footnote 8

The authorship of each of the poetic compositions included in the Carmina is attributed to each of the ‘twelve sages’ that lend their name to the book. In this case, the hexameter is assigned by the compiler to an undiscovered author called Pompilianus, Pompelianus, or Pompeianus, according to the different variations in the manuscripts.Footnote 9 The inscription from Belsinon, however, earlier in date than the monostichs, reinforces the suspicion that this is a fictitious author. It is more appropriate, perhaps, to consider it an anonymous creation that may already have spread widely across the western Mediterranean more than a century and a half before the compilation of the Carmina. It is interesting to note, moreover, that this is the first evidence that confirms the popularity of the duodecim scripta in Spain, where no tabulae lusoriae have yet been discovered that are unequivocally associated with this game.Footnote 10