Published online by Cambridge University Press: 11 February 2009

In the history of Archaic Greece no event stands out so clearly as the First Sacred War. The War took place in the years round 590 B.C., and ended with the capture and destruction of the great city of Crisa at the hands of a coalition of powers which included Sicyon, Athens, and Thessaly. Our sources provide a wealth of detail–the causes of the War, the names of half-a-dozen commanders and champions, the stages of the fighting, the victory celebrations and dedications which ensued, certain Delphic oracles and Amphictyonic decrees.

page 38 note 1 Besides the familiar abbreviations I use the following: Aly, W. (1950Google Scholar) = ‘Zum neuen Strabon-Text’, PP 5 (1950), 228–63Google Scholar; Bickermann, E. and Sykutris, J. (1928) = ‘Speusippos' Brief an König Philipp’, BSAW IxxxGoogle Scholar, no. 3; Bousquet, J. (1956)Google Scholar = ‘Inscriptions de Delphes, 7: Delphes et les Asclépiades’, BCH 80 (1956), 579–93Google Scholar; Defradas, J. (1954) = Les Thémes de la propagande delphiqueGoogle Scholar; Dor, L., Jannoray, J., and H. and van Effenterre, M. (1960)Google Scholar = Kirrha: Étude de préhistoire phocidienne; I üring (1957)Google Scholar = Aristotle in the Ancient Biographical Tradition; Forrest, G. (1956)Google Scholar = ‘The First Sacred War’, BCH 80. 33–52CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Guillon, P. (1963) = Études béiotiennes: La Boucher d'Héracles et I'histoire de la Grèce centrale dans la période de la première guerre sacréeGoogle Scholar; Jacoby, F. (1902) = Apollodors Chronik; id. (1904) = Das Marmor PariumGoogle Scholar; Jannoray, J. (1937)Google Scholar = ‘Krisa-Kirrha et la première guerre sacrée’, BCH 61 (1937), 33–43CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Parke, H. W. and Boardman, J. (1957)Google Scholar = ‘The Struggle for the Tripod and the First Sacred War’, JHS 77 (1957), 276–82CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Parke, H. W. and Wormell, D. E. W. (1956) = The Delphic OracleGoogle Scholar; Pomtow, H. (1918)Google Scholar = ‘Delphische Neufunde III: Hippokrates und die Asklepiaden in Delphi’, Klio 15 (1918), 303–38Google Scholar; Roger, J. and van Effenterre, H. (1944)Google Scholar = ‘Krisa-Kirrha’, RA ser. 6, no. 21; Sordi, M. (1953)Google Scholar = ‘La prima guerra sacra’, RF1C 81 (1953), 320–46Google Scholar; Wade-Gery, H. T. (1936) = ‘Kynaithos’, in Greek Poetry and Life: Essays PresGoogle Scholar. to Murray, G., pp.56–78Google Scholar; von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff, U. (1893)Google Scholar = Aristoteles und Athen; id. (1922) = Pindaros.Google Scholar

page 38 note 2 Wilamowitz, (1893), i. 20.Google Scholar

page 38 note 3 ‘The First Sacred War’ is a modern term; modern too is the numbered series of Sacred Wars-the Second of the mid-fifth century, the Third of 356–346, and the Fourth of 339–338. I adopt this usage for convenience, even though it has no warrant in the ancient sources, which apply the term ![]() only to wars of the fifth and fourth centuries, though not to the war of 339–338. The Spartan offensive of the mid-fifth century which ousted the Phocians from Delphi (until Athens brought them back again two years later) is referred to by Th. i. 112.5 as ‘the socalled Sacred War’; sch. Ar. Av. 556 distinguishes the Spartan campaign and the Athenian riposte as two successive ‘sacred wars’, though it is not clear whether this duplication was authorized by any of the writers cited, namely (besides Th. ) Theopomp, . FGH 115Google Scholar F 156, Philoch, , FGH 328Google Scholar F 34, and Eratosth, . FGH 241Google Scholar F 38. The conflict of 356–346 is often called ‘the Sacred War’, e.g. in the title of Callisthenes’ contemporary account, FGH 124Google Scholar F 1. By contrast the ‘First Sacred War’ is called

only to wars of the fifth and fourth centuries, though not to the war of 339–338. The Spartan offensive of the mid-fifth century which ousted the Phocians from Delphi (until Athens brought them back again two years later) is referred to by Th. i. 112.5 as ‘the socalled Sacred War’; sch. Ar. Av. 556 distinguishes the Spartan campaign and the Athenian riposte as two successive ‘sacred wars’, though it is not clear whether this duplication was authorized by any of the writers cited, namely (besides Th. ) Theopomp, . FGH 115Google Scholar F 156, Philoch, , FGH 328Google Scholar F 34, and Eratosth, . FGH 241Google Scholar F 38. The conflict of 356–346 is often called ‘the Sacred War’, e.g. in the title of Callisthenes’ contemporary account, FGH 124Google Scholar F 1. By contrast the ‘First Sacred War’ is called ![]() at Str. 9.3.4, 3.10 (though at 9.3.8 we hear of ‘the Phocian or Sacred War’ of 356–346);

at Str. 9.3.4, 3.10 (though at 9.3.8 we hear of ‘the Phocian or Sacred War’ of 356–346); ![]() at Ath. 13.10, 560B (where a detail concerning ‘the Crisaean War’ is cited from Callisthenes' book on ‘the Sacred War’ of 356–346); and

at Ath. 13.10, 560B (where a detail concerning ‘the Crisaean War’ is cited from Callisthenes' book on ‘the Sacred War’ of 356–346); and ![]() in [Thessalus] presb. (Hp. ix 422 Littré beside

in [Thessalus] presb. (Hp. ix 422 Littré beside ![]() Likewise the Fourth Sacred War is called ‘the war at Amphissa’ at D. 18. 143 (where the orator also deplores the danger of an ‘Amphictyonic war’ directed against Athens).Google Scholar

Likewise the Fourth Sacred War is called ‘the war at Amphissa’ at D. 18. 143 (where the orator also deplores the danger of an ‘Amphictyonic war’ directed against Athens).Google Scholar

page 39 note 1 In the eyes of Parke, and Wormell, (1956), i. 109, the early Amphictyons were disinterested patrons of the sanctuary and the Games, who also pondered ‘general questions’ about the welfare of Greece, but never mixed in the working of the oracle, ‘except in so far as the Delphians chose to adopt the general Amphictyonic policy’. This is not the tone of h. Ap. 540–3, if these lines refer to the Amphictyons (of which more below).Google Scholar

page 40 note 1 Busolt, , Gr. Gesch.2 i. 690–2Google Scholar; Pieske, , RE xi. 2 (1922), 1887–1989Google Scholar, Krisa, s.v.; Wilamowitz, (1922), p.71Google Scholar; Aly, (1950), p.251Google Scholar; Parke, and Wormell, (1956), i. 99–100Google Scholar, cf. 62, 92. Others distinguish betweei Crisa as a Mycenaean and Homeric city, supposedly occupying an acropolis site, and Cirrha as the harbour town and the target of the Sacred War: so Jannoray, (1937)Google Scholar; Sordi, (1953), p.320Google Scholar; and Jannoray, Dor, and H. and van Effenterre, M. (1960), pp.13–6.Google Scholar

page 40 note 2 For full references to the excavation reports see Alin, P., Das Ende der Myken. Fundstätten auf dem Gr. Festland pp.130–2Google Scholar, and Desborough, V. R. D'A., The Last Mycenaeans and their Successors, p.125. The excavators spoke of Granary-Style pottery, but Alin, who discusses the published material very thoroughly, concludes that they applied the term to L. H. IIIB types, and that the settlement probably did not ou this period, although a tenuous reoccupation after the catastrophe is not quite excluded.Google Scholar

page 40 note 3 The consequences for the story of the Sacred War were firmly drawn by Jannoray, (1937)Google Scholar and by Roger, and van Effenterre, (1944).Google Scholar

page 41 note 1 Jannoray, (1937), pp.39–40Google Scholar, and Roger, and van Effenterre, (1944), pp.18–20Google Scholar, describe their trial excavations at the site of the harbour town, now called Xeropigado; the remains which they uncovered, on the hill Magoula and on the low ground between Magoula and the sea, range In date from the sixth to the fourth century; at Magoula the traces of this period directly overlie the prehistoric settlement. For Jannoray, in 1937Google Scholar these findings were evidence enough of the Archaic city of the Sacred War; Roger and van Effenterre are rightly sceptical, but their suggestion that further remains may lie close at hand, concealed by the alluvium of the Pleistus, is unconvincing; as Frazer notes on Paus. 10.37.4, Ulrichs, H. N. in 1837 found many scattered ruins of the harbour town, which were doubtless plundered later by the builders of Itea and Xeropigado (n.l, p.48 below).Google Scholar

page 41 note 2 Some are still optimistic, however. The city may have lain at some unknown spot in the plain, say Roger, and van Effenterre, (1944), pp.19–20Google Scholar, and also Jannoray, Dor, and H. and van Effenterre, M. (1960), p.15Google Scholar. But for a powerful and prosperous city we want a defensible and advantageous site, which will include a harbour and an acropolis. According to Sordi, (1953), pp.334–7Google Scholar, the second stage of the Sacred War was fought against a great stronghold (which she calls ‘Kraugallion’ after Aeschines and others) on the south slope of Mount Cirphis, to be identified with the slight traces of an ancient settlementat Desphina. As already noted by Bolte, , RE xi. 1 (1921), 507–8Google Scholar, s.v.

Kirphis, this was an unimportant place, and cannot possibly be ‘the greatest city’ of the Crisaeans as described by [Thessalus], who beyond all doubt means the site at Ay. Georghios (for Sordi's answer to this see n.2, p.69 below).

page 41 note 3 As L-P observe, lines 9–12 of the papyrus suggest the story of Phalanthus’ shipwreck in the Crisaean Gulf (Paus. 10.13.10).

page 41 note 4 It may be that the name Crisa/Cirrha is related to such words as ![]() ‘orangecoloured’,

‘orangecoloured’, ![]() ‘varicose vein’,

‘varicose vein’, ![]()

![]() ‘fox’; cf. Wilamowitz, (1922), p.71Google Scholar.

‘fox’; cf. Wilamowitz, (1922), p.71Google Scholar. ![]() the name of the mountain south of Parnassus which comes down to the sea by the harbour town of Cirrha, is superficially alike but intractable from a linguistic point of view (though Aly, (1950), p.251, tells us that the resemblance between Crisa and Cirrha is ‘only accidental’ and that Cirrha ‘belongs rather with Kirphis’).Google Scholar

the name of the mountain south of Parnassus which comes down to the sea by the harbour town of Cirrha, is superficially alike but intractable from a linguistic point of view (though Aly, (1950), p.251, tells us that the resemblance between Crisa and Cirrha is ‘only accidental’ and that Cirrha ‘belongs rather with Kirphis’).Google Scholar

page 42 note 1 At P. 5.34–9 the charioteer Carrhotus, coming from Cyrene to compete in the hippodrome, ‘went past the Crisaean hill into Apollo's level glen’,![]()

![]() ‘The Crisaean hill’ is probably the mountain spur north-east of the harbour town (called Myttikas according to Frazer on Paus. 10. 37.5). At P. 6.18 a chariot victory is said to take place ‘in the folds of Crisa’,

‘The Crisaean hill’ is probably the mountain spur north-east of the harbour town (called Myttikas according to Frazer on Paus. 10. 37.5). At P. 6.18 a chariot victory is said to take place ‘in the folds of Crisa’, ![]() so too at b. Ap. 269 the future hippodrome is located ‘at Crisa under a fold of Parnassus’ If Leake and others have correctly placed the hippodrome at the site called Komara at the northern edgs of the plain (§ VIII below), it is in fact enclosed in a fold formed by two outrunners of Parnassus.

so too at b. Ap. 269 the future hippodrome is located ‘at Crisa under a fold of Parnassus’ If Leake and others have correctly placed the hippodrome at the site called Komara at the northern edgs of the plain (§ VIII below), it is in fact enclosed in a fold formed by two outrunners of Parnassus.

page 42 note 2 Another fr. of Hecat, ., FGH 1 F 105Google Scholar, cited by St. Byz. s.v. Chaonia, appears to locate the ‘Cirrhaean’ Plain and Gulf (MSS. ![]() ) In Chaonia. The text has not been convincingly emended or explained. Jacoby, , SPAW (1933), 746Google Scholar n.2, favours B. A. Miiller's

) In Chaonia. The text has not been convincingly emended or explained. Jacoby, , SPAW (1933), 746Google Scholar n.2, favours B. A. Miiller's ![]() Hammond, N. G. L., Epirus (1967), pp.451Google Scholar, 458, 478, adopts the name ‘Ciraeus’ for the shallow gulf north of Buthrotum and the plain behind it, mainly on the ground that this is the only sizeable coastal plain in Chaonia; his remark that ‘the name is probably earlier here’ than in central Greece presupposes an emigration of Greek speakers from Epirus.

Hammond, N. G. L., Epirus (1967), pp.451Google Scholar, 458, 478, adopts the name ‘Ciraeus’ for the shallow gulf north of Buthrotum and the plain behind it, mainly on the ground that this is the only sizeable coastal plain in Chaonia; his remark that ‘the name is probably earlier here’ than in central Greece presupposes an emigration of Greek speakers from Epirus.

page 42 note 3 The name is taken to denote the plain by Defradas, (1954), p.57Google Scholar, and Guillon, (1963), pp.85–8.Google Scholar

page 42 note 4 Frazer on Paus. 10.75.5; Allen, Halliday, and Sykes ad loc; Simpson, R. Hope and Lazenby, J. F., The Cat. of the Ships in Homer's II. (1970), p.41Google Scholar. Wade-Gery, (1936), p.62Google Scholar n.l, who identifies Crisa with Ay. Georghios, recognizes the setting at 282–6 as ‘the Kastalian Glade’, and says that the name Crisa is here applied to it because the city ‘still controlled the Oracle’. This would be a curious procedure even if the city were as near as Ay. Georghios.

page 43 note 1 Line 230 has a similar apposition, ![]()

page 43 note 2 Only Guarducci, , SMSR 19–20 (1943–1946), 87–8, has hitherto equated the ‘Crisa’ of the Hymn with the harbour town; she does not examine the usage closely.Google Scholar

page 43 note 3 Frazer on Paus. 10.37.5 regards the plain between Parnassus and the sea as falling into two parts, a southern and a northern, divided by mountain spurs advancing from E and W: the southern pan he says, is the Cirrhaean plain, ‘still almost as treeless as it was in the days of Paus.’ (but Paus. thus describes the whole expans of plain as far as Parnassus) and hence to be identified with the consecrated territory, whereas the northern part is ‘the Crisaean plain proper’–though he admits that the term is sometimes applied to the whole plain. No one has followed Frazer here.

page 43 note 4 It is clear that ![]() in Th. means the Corinthian Gulf; Str. calls this

in Th. means the Corinthian Gulf; Str. calls this ![]() (9.2.15) and applies the term

(9.2.15) and applies the term ![]() to the Bay of Itea (9.1.1, 3.1, 3.3).

to the Bay of Itea (9.1.1, 3.1, 3.3).

page 43 note 5 Aly, (1950), pp.250–2 thinks it significant that whereas Str. and Ath. speak of ‘the Crisaean War’, the conquered people are called not ‘Crisaeans’ but ‘Cirrhaeans’ in sch. Pi. P. hyp. b, d, Ath., and Plu. This circumstance-which he calls dieser ganze Überlieferungskomplex–leads him to infer that the war was originally directed against the great city of Crisa (Ay. Georghios) and that after the fall of Crisa ‘unexpected resistance’ continued in the harbour town of Cirrha. But the sources allow no such distinction, for it is precisely the victims of the first stage of the fighting who are called ‘Cirrhaeans’ in hyp. b, d, and indeed the city destroyed in the first stage is called ‘Cirrha’ in hyp. d (as also at marm. Par, A 37).Google Scholar

page 44 note 1 The oracle that requires Apollo's precinct to meet the sea (D.S. ‘ix’, fr. 16; Paus. 10.37.6; wrongly inserted at Aeschin. 3.112) might have been issued at either stage; Paus. puts it before the poisoning. In the summary paraphrase of Polyaen. 3.5 the sea must touch, not Apollo's precinct, but ‘the Cirrhaean land’; and ‘the Cirrhaeans made light of it, being very far removed from the sea’; but since the Cirrhaean land itself adjoined ‘the sacred land stretching to the sea’, Cleisthenes was able to satisfy the oracle by dedicating ‘both the city and the Cirrhaean land’. It seems likely that the oracle was thus amended in order to fit the version of the War which placed Cirrha/Crisa at Ay. Georghios (discussed below).

page 45 note 1 The original oracle was evidently already known to Ephorus as the source of D.S. ‘ix’, fr. 16 (so Wilamowitz, (1893), i. 18 n.29).Google Scholar

page 45 note 2 At Dion. Calliph. 81 ![]() is Harduin's certain correction of MS.

is Harduin's certain correction of MS. ![]()

page 46 note 1 Paus. 10.37.4 gives the distance from Cirrha to Delphi as 60 stades, Harp, . s.v. Kirrhaion pedion as 30. Harp.'s figure is much too small; Str. and Paus. are in the proper range; but the windings of the upper road between Chrysd and Delphi complicate the reckoning, as Frazer observes. Cirrha is not strictly ‘opposite Sicyon’, but in Str.'s day there were no towns of any account between Sicyon and Aegium far to the west (8.7.4–5).Google Scholar

page 46 note 2 The identification is affirmed by Aly, (1950), p.251. Noting that Str. is commonly understood to place Crisa on the coast, Aly brands this opinion as ‘false’, and attempts a different explanation. The words ![]()

![]() says Aly, describe the plain not as lying inland from Cirrha, but as meeting the sea west of Cirrha in the vicinity of modern Itea. This rendering of

says Aly, describe the plain not as lying inland from Cirrha, but as meeting the sea west of Cirrha in the vicinity of modern Itea. This rendering of ![]() is extremely dubious, but in any case has no bearing that I can see on what follows, viz.

is extremely dubious, but in any case has no bearing that I can see on what follows, viz. ![]()

![]()

![]() which can only mean that Crisa lies on the coast between Cirrha and Anticyra. Perhaps it was in Aly's mind to interpret the passage as locating Crisa somewhere on the northern periphery of the Crisaean plain, but then he need not have troubled about

which can only mean that Crisa lies on the coast between Cirrha and Anticyra. Perhaps it was in Aly's mind to interpret the passage as locating Crisa somewhere on the northern periphery of the Crisaean plain, but then he need not have troubled about ![]() for Ay. Georghios lies north-east of Cirrha. On top of this confusion Aly has overlooked 9.3.1, where Crisa is expressly said to lie on the sea itself.Google Scholar

for Ay. Georghios lies north-east of Cirrha. On top of this confusion Aly has overlooked 9.3.1, where Crisa is expressly said to lie on the sea itself.Google Scholar

page 46 note 3 That Crisa should be sought in this area was suggested (without reference to Str.) by Jannoray, Dor, and H. and van Effenterre, M. (1960), p.15; but as they admit, no traces have ever been observed.Google Scholar

page 46 note 4 For the manuscript readings see Aly, (1950), p.251, together with the footnote added by Sbordone.Google Scholar

page 47 note 1 Aeschines boasted that in 340/39 he and other Amphictyonic delegates, reacting to Amphissa's encroachments on the sacred land, ‘went down into the plain of Cirrha and demolished the harbour and burnt the houses before withdrawing again’ (3.123). In order to evade responsibility for bringing Philip into Greece, Aeschines must exaggerate the indignation of the Amphictyons and the severity of their reprisals against Amphissa. The harbour town of Cirrha figures in Delphic inscriptions before and after this date without any perceptible change; we ought not to imagine that it was laid in ruins by Aeschines and his colleagues. Now Str. 9.3.4 devotes a couple of sentences to these events, but the destruction of Cirrha which he previously alleged does not belong here, for he associates the Amphissians with Crisa, not Cirrha: ‘they revived Crisa, and tilled once more the plain that had been cursed by the Amphictyons, and proved harsher to foreigners than the Crisaeans of old had been.’

page 48 note 1 The modern settlements on the coast date from the nineteenth centuryItea fron 1837, Xeropigado from 1871: see Lerat, L., Les Locriens de l'ouest i. 163.Google Scholar

page 48 note 2 Wilamowitz, (1922), p.71Google Scholar n.4, 73 n.O regarded the hero ![]() as a disguised form of

as a disguised form of ![]() in conformity with his view that the Delphians and others sought to abolish all memory of Crisa by substituting

in conformity with his view that the Delphians and others sought to abolish all memory of Crisa by substituting ![]() for earlier names like

for earlier names like ![]() (in the Troad!) and

(in the Troad!) and ![]() and also by turning

and also by turning ![]() into

into ![]() (but cf. Der Gl. der Hell. ii. 32 n.2); this is very far fetched.Google Scholar

(but cf. Der Gl. der Hell. ii. 32 n.2); this is very far fetched.Google Scholar

page 49 note 1 Wade-Gery, (1936)Google Scholar; West, M. L., CQ 69 (1975), 161–70.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

page 49 note 2 Jacoby, , SPAW (1933), 749Google Scholar n.l; Allen, Halliday, and Sykes, pp.185, 199–200Google Scholar; Wade-Gery, (1936), pp.62–8Google Scholar; Defradas, (1954), pp.55–85Google Scholar; Parke, and Wormell, (1956), i. 1078Google Scholar; Guillon, (1963), pp.85–98Google Scholar; Lesky, A., Gesch. der Gr. Lit.2, p.106Google Scholar; West, , CQ 69 (1975), 165.Google Scholar

page 49 note 3 Wilamowitz, (1922), p.74Google Scholar; Guarducci, , SMSR 19–20 (1943–1946), 86–7Google Scholar; Forrest, (1956), pp.34–5Google Scholar; Fontenrose, J., Univ. Calif. Publ. Class. Arch. iv. 3 (1960), 222Google Scholar; Richardson, N. J., The Horn. H. to Dem. (1974), pp.11 n.2, 332.Google Scholar

page 49 note 4 Wade-Gery, (1936), p.64–asGoogle Scholar part of a revision soon after the Sacred War; Forrest, (1956), pp.34–5Google Scholar, 42–4; Parke, and Wormell, (1956), i. 107–8.Google Scholar

page 50 note 1 Jacoby, (1904), pp.33–5.Google Scholar

page 50 note 2 Gomme ad loc. does not mention the First Sacred War but finds two other exceptions to Th.'s rule, namely the conquests of early Sparta and of Pheidon of Argos. It seems to me that these wars, being fought by a single state against its neighbours, are not exceptions at all, unless with Gomme we interpret the first sentence of 1.15.2 to mean ‘there was no war that led to any real accession of power’; but could Th. possibly mean that?

page 51 note 1 This passage of Th. and the Phocian chapters of Hdt. were previously adduced by Guillon, (1963), p.57, as incompatible with the tradition of the First Sacred War. But he continued to believe in the main events of the War.Google Scholar

page 51 note 2 Had it always been known that both Solon and Alcmeon were deeply concerned in the War, we should expect the Attic chroniclers to dwell upon the subject, and the results ought then to be canvassed by the Alexandrian commentators on P., who drew freely on these chroniclers. Instead sch. Pi. P. hyp. b and d appear to use one source only for the Sacred War (apart from Euphorion's passing mention of Eurylochus), namely the Register of Pythian Victors (§§ V–VI below). Admittedly the silence of the Attic chroniclers is not a strong argument against the authenticity of the War, but it is worth observing that they are silent, inasmuch as some critics have persistently but falsely stated that the tradition is in fact indebted in some measure to the Attic chroniclers. Wilamowitz, (1893), i, 13–14Google Scholar asserted that Aeschines’ notice of Solon at 3.108 could only derive from an Attic chronicler (‘This conclusion, which perhaps seems too bold at this point, will be self-evident to one who has read my book through’); in truth Aeschines might have consulted any of the three contemporary treatments that we know of, Callisth. On the Sacred War, Ar. and Callisth.'s Register of Pythian Victors, or the researches of Antipater of Magnesia, , FGH 69Google Scholar F 2; or–since the Sacred War was very much in the air-he might have relied on hearsay at Athens or even at Delphi, where he had recently been Pylagorus. Citing these pages of Wilamowitz, Jacoby went a few steps further and spoke of ‘extensive’ comment by the Attic chroniclers and of ‘abundant’ traces of such comment ((1904), p.102, and again in his note on FGH 239Google Scholar F 37–8: according to Jacoby it was an Atthis that supplied the Parian chronicler with his dates for the War and for the origin of the Pythian Games. Jacoby also conjectures that Androtion, who regarded the original ‘Amphictyony’ as nothing more than a gathering of neighbours (FGH 324 F 58), offered this explanation while recounting the First Sacred War; but nowhere else is the lore of Amphictyonic origins connected with the Sacred War; and it is much more likely that Androtion spoke of the Amphictyony in connection with the Athenian king Amphictyon, for in all other sources the Amphictyony is founded by one Amphictyon, either the Attic king or a homonym.Google Scholar

page 52 note 1 As Bickermann, (1928), pp.27–9, explains, Antipater aimed to establish Philip's legal title to places like Pallene, Torone, Amphipolis, and Ambracia: they had all been justifiably seized by Heracles in reprisal for wrongdoing, and then duly placed on deposit with trustees whom he appointed.Google Scholar

page 53 note 1 Among extant sources Antipater is in fact the first to describe either Phlegyans or Dryopians as offenders against Apollo's shrine. To be sure, a sch. on Il. 13.302, after relating at length the conflict between Thebes and the Phlegyans, adds that ‘they also burned the temple of Apollo at Delphi’, and appears to ascribe the latter tale as well as the former to Pherecydes (FGH 3Google Scholar F 41e); but the very cursory mention of the temple-burning, when set beside several other notice: of Pherecydes on the Phlegyans (FGH 3Google Scholar F 41b, c, d), makes it virtually certain that the mythographer treated only the Phlegyan encroachment on Thebes. The Phlegyans are properly at home in the region of Orchomenus (b. Ap. 278). The next writer after Antipater to bring the Phlegyans to Delphi is Demophilus in the last book of Ephorus' Histories (FGH 70Google Scholar F 93). As for the Dryopians, Heracles drove them out at che bidding of the Delphic oracle (B. fr. 4 inell8), but their offence was against Heracles and perhaps Ceyx, not against Delphi. So it is likely enough that the Phlegyans and Dryopians, stock villains both, were brought to Delphi to provide a mythical paradigm for the Phocian villainy of the Third rhird Sacred War. But we must not attribute this bold step to Antipater, whose creative pagination seems very limited.

page 54 note 1 Aeschines tells his Athenian audience in 343, as he professedly told Philip in 346, that the Amphictyons in old days–seemingly at their first meeting, though Aeschines is not quite clear on this point–swore a great oath never to devastate a member city or subject it to the rigours of siege warfare; and he quotes the archaic-sounding oath. Now although Crisa is not usually regarded as a member of the Amphictyony, the treatment which she received from the Amphictyons plainly contravenes the spirit if not the letter of the oath, and modern scholars have been put to some trouble to explain the inconsequence. It is simpler to infer that when Aeschines and doubtless others before him held up the Amphictyonic oath as a pattern of conduct, the First Sacred War had not been heard of. Whether the oath is in any sense authentic may be doubted: the question has not been much advanced, so far as I can see, by the text of the ‘Greek Oath’ inscribed at Acharnae in the mid-fourth century, which contains the same undertaking in the same language, but in favour of the cities leagued against Xerxes. Even if the Greek Oath in both the epigraphic and the literary versions is a figment, as the majority opinion reasonably holds, there is no telling whether the formulas inserted in the Acharnian text came froma well-known model such as the Amphictyonic oath might have been, or from some indiscriminate stock of such things (cf. Daux, G., ‘Serments amphictioniques et serments de Plarfes’, in Stud. Pres. to D. M. Robinson ii. 775–82).Google Scholar

page 54 note 2 The notion that Menaechmus of Sicyon dealt with the Sacred War and gave a leading role to Cleisthenes (so e.g. Parke, and Wormell, (1956), i. 104–5Google Scholar) depends upon Boeckh's treatment of sch. Pi. N. 9 inscr., which was certainly misguided. ‘The Halicarnassian’ there cited cannot be Hdt., as Boeckh thought, and though something has dropped out of the citation, another authority such as Menaechmus is not wanted in the lacuna; ‘the Halicarnassian’ told of Cleisthenes’ blockading Crisa and founding the Pythian Games at Sicyon out of the spoils of war. As Wilamowitz, (1893), i. 18Google Scholar n.27, saw, ‘the Halicarnassian’ will be Dionysius, who might well treat the foundation of the Sicyonian festival in his work ![]() (FGH 251, where this passage is not canvassed, however.)Google Scholar

(FGH 251, where this passage is not canvassed, however.)Google Scholar

page 54 note 3 Vatic, gr. 64 (Bickermann, and Sykutris, (1928), p.7).Google Scholar

page 55 note 1 Jacoby, on FGH 124Google Scholar F 1 and Pearson, L., The Lost Hist, of Alex, the Great, p.28, thought of ‘an introduction’ to the book.Google Scholar

page 55 note 2 Jacoby, , RE x 2 (1919), 1685Google Scholar s.v. Kallisth. 2, and again on FGH 124 T 23.Google Scholar

page 55 note 3 The accounts were inscribed under the archon Caphis, formerly assigned to 331/0. The adjustment of the ‘Aristotle publication-date’ (not a happy term) was pointed out by Lewis, D. M., CR N.S. 8 (1958), 108.Google Scholar

page 55 note 4 The catalogue of Aristotle's works also has the title Olympic Victors (D. L. no. 130; Hsch. no. 122); but as this was only a single volume, beside the three volumes of the Register (of which more below), it must have dealt with some limited aspectperhaps victors in a single event, or disputed names and provenances in the list.

page 55 note 5 Wilamowitz, (1893), i. 13–24Google Scholar; Jacoby, on FGH 239 F 37–8.Google Scholar

page 55 note 6 That it did so was maintained by Pomtow at SIG 3 275 n.6 and by Tod on GHI 187. Dem. Phal.'s reference to Creon as staging an ennaeteric Pythian festival just before the Trojan War (fr. 191 Wehrli, cited by Eust. on Od. 3.267, and perhaps deriving from the Homericus, as Wehrli suggests) must not be taken to prove that the Agonothetae were on record.

page 56 note 1 Jüthner, J., Philostr. über Gymn., pp.109–16.Google Scholar

page 56 note 2 In the Aristotelian Peplus too the Pythian festival had a mythical origin, being founded by the Amphictyons to commemorate the slaying of the serpent (sch. Aristid, . Panath. p.323Google Scholar Dindorf = fr. 637 Rose: according to Phot, ex Helladius, cited by Rose ibid., the work also, described the historical Pythian Games as originating after the fall of Cirrha, but this notice does not accord with the scope of the Peplus or with its treatment of the other great festivals, and can probably be disregarded). It is natural to suppose that the Peplus incorporates the view set forth in the Register.

page 56 note 3 ![]()

![]() runs the entry in Hsch.'s catalogue, which is the only piece of evidence that Menaechmus is earlier than Aristotle; whereas other indications, FGH 131Google Scholar T 1, 4b, imply that he lived a generatior or two later (despite Jacoby, on FGH 131, followed by Pearson and others); and so it might be argued that the entry in Hsch. is merely the inference of some Alexandrian scholar faced with two concurrent works. Alternatively we may postulate two Menaechmi (!) or even several. Jacoby is prepared to distinguish the sculptor who wrote about his art (T 2), but diaeresis could be carried a good deal further.Google Scholar

runs the entry in Hsch.'s catalogue, which is the only piece of evidence that Menaechmus is earlier than Aristotle; whereas other indications, FGH 131Google Scholar T 1, 4b, imply that he lived a generatior or two later (despite Jacoby, on FGH 131, followed by Pearson and others); and so it might be argued that the entry in Hsch. is merely the inference of some Alexandrian scholar faced with two concurrent works. Alternatively we may postulate two Menaechmi (!) or even several. Jacoby is prepared to distinguish the sculptor who wrote about his art (T 2), but diaeresis could be carried a good deal further.Google Scholar

page 56 note 4 At any rate a ![]() would hardly contain a list of victors, as Jacoby observes at FGH Hlb Komm. ii (Noten), 140 n.24; so this was not the point in which Aristotle ‘superseded’ Menaechmus (or possibly anticipated him, as suggested in n.3 above).

would hardly contain a list of victors, as Jacoby observes at FGH Hlb Komm. ii (Noten), 140 n.24; so this was not the point in which Aristotle ‘superseded’ Menaechmus (or possibly anticipated him, as suggested in n.3 above).

page 56 note 5 That Cleisthenes of Sicyon is credited with the first victory in the chariot race, instituted in 582/1 (Paus. 10.7.6), might also be thought to point to Menaechmus (but as was said in n.2, p.54 above, Menaechmus is not our source for Cleisthenes' role in the Sacred War).

page 57 note 1 The only dated victory expressly cited from the Register belongs to Pythiad 24 of 490 B.C. (sch, Pi. /. 2 inscr. = fr. 617 Rose).

page 57 note 2 Cicero makes it clear that Callisth.'s work on the Third Sacred War was a separate monograph, not a part of the Register (Fam. 5.12Google Scholar.2 = FGHT 25).Google Scholar

page 57 note 3 So Düring, (1957), pp.67–9, 90–2, who rejects Moraux's ascription of the catalogue, as of other elements in Aristotle's biography, to Ariston of Chios. In the text of D. L. and Hsch. I follow Düring's careful recension at pp.49 and 86.Google Scholar

page 57 note 4 It is the fixed idea of the Register as a uniform documentary compilation that has prevented scholars from seeing the direct and simple relationship between the Register and the Pythian titles in the Alexandrian catalogue. Düring, (1957), p.339, represents the majority view in equating D. L.'s ![]() with

with ![]() the

the ![]() of the Delphic inscription and in describing this as ‘the original work’, i.e. the very pith and quintessence of the methodical disinterested research that is held to typify Aristotle and his school; D. L.'s

of the Delphic inscription and in describing this as ‘the original work’, i.e. the very pith and quintessence of the methodical disinterested research that is held to typify Aristotle and his school; D. L.'s ![]()

![]() then becomes ‘an extract’ giving the list of musical victors, and D. L.'s

then becomes ‘an extract’ giving the list of musical victors, and D. L.'s ![]() ‘a historical work from which Plu. took the facts mentioned in Sol. 11’; at the same time the title known to Plu.,

‘a historical work from which Plu. took the facts mentioned in Sol. 11’; at the same time the title known to Plu., ![]()

![]() can be identified neither with the ‘historical work’ nor with the documentary work called by this very name at Delphi–it must be a ‘comprehensive title’ for all three works listed by D. L.! No wonder then that Jacoby at FGH Illb Komm. ii (Noten), 140 n.24, abandons the effort of analysis altogether, and postulates ‘a confusion which we cannot comprehend’.Google Scholar

can be identified neither with the ‘historical work’ nor with the documentary work called by this very name at Delphi–it must be a ‘comprehensive title’ for all three works listed by D. L.! No wonder then that Jacoby at FGH Illb Komm. ii (Noten), 140 n.24, abandons the effort of analysis altogether, and postulates ‘a confusion which we cannot comprehend’.Google Scholar

page 57 note 5 In D. L.'s catalogue Rose made two entries out of one by supplementing ![]() (for the first ã does not occur in the best manuscripts). This procedure mars instead of mends the concurrence with Hsch.

(for the first ã does not occur in the best manuscripts). This procedure mars instead of mends the concurrence with Hsch.

page 58 note 1 Legendum ![]() Verbo

Verbo ![]() casu quodum deperdito scriba supplevit titulum sane no turn sed buic locum alienum (Düring).

casu quodum deperdito scriba supplevit titulum sane no turn sed buic locum alienum (Düring).

page 58 note 2 Some have tried to compute the quantity of lettering that 2 minas would buy. The results however have little value–not because contemporary rates are unknown, as Pfeiffer asserts, Hist, of Class. Schol. i. 80 n.7, for in fact the same contractor was paid 4 obols per 100 letters in 334 and a drachma per 100 in 339, the difference no doubt depending on the size and quality of the letters, and Pomtow reasonably used the cheaper rate as the base–but because the contractor may have received other payments for the same task in earlier and later years. In any case it is inconceivable that a three-volume work should have been inscribed in toto. The contractor Deinomachus, otherwise known as Hieromnemon and Councillor, was probably charged with making suitable excerpts.Google Scholar

page 58 note 3 No matter what view we take of the length and completeness of the inscribed text, as also of the period of time spent at the task, it seems to me quite misguided to regard the Delphic undertaking as the actual publication of Ar. and Callisth.'s book, and to speak of 327 as ‘one of the best attested publication-dates in the ancient world’ (so Lewis, D. M., CR N.S. 8 (1958), 108).Google Scholar

page 58 note 4 That Callisth. was with the expedition from the. outset is the modern consensus, argued by Jacoby, , RE x 2 (1919), 1675–1976Google Scholar; Berve, H., Das Alexanderreich ii. 192–3Google Scholar; and Hamilton, J. R., Plu.'s Alex., p.147Google Scholar. Although it may be true that certain frr. of Callisth. dealing with the early stages of the expedition ‘absolutely presuppose an eye-witness’ (so Berve), the eye-witness need not have been Callisth. himself. We may readily believe that Ar. commended Callisth. to Alexander, as many sources say; but the commendation might come at any time. No reliance whatever can be placed on D. L. 5.4, where Ar., on moving to Athens, introduces Callisth. to Alexander; for this brief, bold sketch of Callisth.'s career has him carried round in an iron cage at the end and then thrown to a lion. Nor can the story of the Recension of the Casket (Str. 13.1.27; Plu, . Alex. 26Google Scholar.1–2) be pressed to show that Callisth. and Alexander were on familiar terms ‘before the conquest of Persis’. On the other hand the tradition that Callisth. arrived late in Alexander's camp is firm and consistent (Plu, . Alex. 53.1, Mor. 1043D; Just. 12.6.17; V. Max. 7.2 ext. 11; Amm. Marc. 18.3.7); and there is no reason why this detail should be invented (it scarcely enhances the story of Callisth.'s concern for Olynthus, as Berve holds).Google Scholar

page 59 note 1 According to Jacoby, , RE x 2 (1919), 1685–6Google Scholar, and again on FGH 124Google Scholar T 23, the monograph belongs in the 340s, soon after the end of the War; the Register is linked to the monograph in theme, and may or may not have directly followed it. During (1957), p.340, dates the Register ‘between 340 and Aristotle's return to Athens in 3 34’, but not for any compelling reason.

page 59 note 2 Speusippus' Let. to Phil, is dated by internal evidence to the late summer of 342 (Bickermann, (1928), pp.29–38), when Callisth.'s monograph on the Third Sacred War must have been before the public, and perhaps also the Register of Pythian Victors or a part of it. Needless to say, we should not expect Speusippus to mention Antipater's debt to Callisth. or to Callisth. and Ar. jointly, supposing that he was aware of it. The venomous head of the Academy derides Isocrates at length for the ineptitude of his recent Address to Philip, and also rounds on Theopompus, said to be residing at Philip's court. There is no word of Ar. or Callisth.; this means, not that Speusippus was well disposed or indifferent to these rivals, but that they were too close to Philip for him to venture an attack.Google Scholar

page 60 note 1 FGH Ulb Komm. i (Text), 214–5, ii (Noten), 139–40. Admittedly the term ![]() is applied to ‘the notices of public business issued by officials, which in the Hellenistic period were often published at the end of the year wholly or in excerpt on stone or wood’; but it is unlikely that Plu. intended the word in any technical sense.Google Scholar

is applied to ‘the notices of public business issued by officials, which in the Hellenistic period were often published at the end of the year wholly or in excerpt on stone or wood’; but it is unlikely that Plu. intended the word in any technical sense.Google Scholar

page 60 note 2 As Jüthner, , Philostr. über Gymn., p. 110, observes, the use of the term ![]()

![]() for a literary list of Olympic victors conforms to Paus.' habit of citing recondite local tradition wherever possible. But it may well be that the recensions of the Olympic victor-list which circulated widely in Imperial times were actually seen to by the administrators of the sanctuary; so too the Pythian victor-list known to Plu.Google Scholar

for a literary list of Olympic victors conforms to Paus.' habit of citing recondite local tradition wherever possible. But it may well be that the recensions of the Olympic victor-list which circulated widely in Imperial times were actually seen to by the administrators of the sanctuary; so too the Pythian victor-list known to Plu.Google Scholar

page 61 note 1 The dates ought to have been settled long ago by Jacoby's, analyses, (1902), pp.168 n.10, 169 n.11, 170 n.12, and (1904), PP:102–5, 165–7.Google Scholar

page 61 note 2 The dates that are certainly inclusive run from A 45 to A 66; in A 39–44 the system is in doubt; our two entries come just before, A 37–8. I speak of ‘exclusive’ and ‘inclusive’ reckoning for convenience only; Cadoux, T. J., JHS 68 (1948), 83–6, has argued convincingly that so far as arithmetic goes, the Parian must be counting exclusively throughout, but that at A 45 or thereabouts he turned from one source to another and mistook the terminal year of his second source; on this view the terms ‘orthodox’ and ‘unorthodox’ dating are more accurate.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

page 61 note 3 Miller, M., Klio 37 (1959), 46–7CrossRefGoogle Scholar, followed by Samuel, A. E., Gr. and Rom. Chronol., p.202Google Scholar, dates Damasias to 586/5 (despite the plain arithmetic of the Parian Marble, which is dismissed as ‘error’). Yet their interpretation of the Pindaric scholia and of Const. Ath. 13.2 cannot in fact be sustained. Hyp. b, the better form of the Pindaric scholium, does not say that the Pythian Gaines were founded in the sixth year after Simon; see below. At Const. Ath. 13.2Google Scholar![]() is a perfectly commonplace expression meaning ‘after the same interval’ (cf. Smyth, , Gr. Gram. 1685 1 c); adopted here for the sake of variatio after two five-year intervals have already been mentioned: it is not a ‘curious phrase’, and cannot mean ‘still within the same period’ (first suggested, I believe, by von Fritz and Kapp), which would be rather

is a perfectly commonplace expression meaning ‘after the same interval’ (cf. Smyth, , Gr. Gram. 1685 1 c); adopted here for the sake of variatio after two five-year intervals have already been mentioned: it is not a ‘curious phrase’, and cannot mean ‘still within the same period’ (first suggested, I believe, by von Fritz and Kapp), which would be rather ![]() So this passage too gives the date 582/1 for Damasias (n.5 below).Google Scholar

So this passage too gives the date 582/1 for Damasias (n.5 below).Google Scholar

page 61 note 4 Although Sosicrates, doubtless drawing on Apollodorus, placed Solon's archonship in 594/3 (D. L. 1.62), it is sometimes held that Const. Ath. 13Google Scholar.1–2, 14.1 implies a date two years later; and the date accepted by the Const. Ath. matters here, because the same archon list will have been used in the Register of Pythian Victors, written perhaps fifteen or twenty years earlier. No matter how we interpret or evade the statement of Const. Ath. 14.1 that Peisistratus first came to power ‘in the thirty-second year after the law-giving, in the archonship of Corneas’, it seems to me that 594/3 is the year indicated for Solon's archonship at 13.1, inasmuch as the three five-year intervals that follow can only lead to the dates 590/89, 586/5, and 582/1 for the two anarchies and the first year of Damasias respectively: see Cadoux, , JHS 68 (1948), 93–9. ![]() at marm. Par. A 38 means not ‘the second year of Damasias’, as Samuel has it (and many others before him), but ‘the second Damasias’, with reference to the homonymous archon of 639/8 (D. H. 3.36.1); A 36, as Jacoby observes, speaks of

at marm. Par. A 38 means not ‘the second year of Damasias’, as Samuel has it (and many others before him), but ‘the second Damasias’, with reference to the homonymous archon of 639/8 (D. H. 3.36.1); A 36, as Jacoby observes, speaks of ![]()

![]() For if 582/1 were in fact the second year of Damasias, we should expect our other, better sources to say so (

For if 582/1 were in fact the second year of Damasias, we should expect our other, better sources to say so (![]()

![]() or the like); after all, the Pindaric scholia are doubly precise and reproduce the Register of Pythian Victors, and Dem. Phal. wrote up a Register of Archons, whether or not fr. 149 Wehrli came from this work; here Dem. dates the emergence of the Seven Sages to Damasias simpliciter, evidently synchronizing this occasion with the first Pythiad in the light of the well-known ties between the Sages and Delphi (Wehrli's comment is off the mark).CrossRefGoogle Scholar

or the like); after all, the Pindaric scholia are doubly precise and reproduce the Register of Pythian Victors, and Dem. Phal. wrote up a Register of Archons, whether or not fr. 149 Wehrli came from this work; here Dem. dates the emergence of the Seven Sages to Damasias simpliciter, evidently synchronizing this occasion with the first Pythiad in the light of the well-known ties between the Sages and Delphi (Wehrli's comment is off the mark).CrossRefGoogle Scholar

page 61 note 5 Whether 582/1 is the true date we can never know. Paus. 10.7.4 gives 586/5 as the first Pythiad, and has taken some hard words from Wilamowitz and Jacoby, who postulate confusion with the ‘money festival’ of 591/0. But as we saw, it is quite possible that Pausanias’ system goes back to Menaechmus of Sicyon and so antedates Ar. and Callisth. (on the usual view of Menaechmus). Pausanias’ statement that athletes received substantial prizes at the first Pythiad, but never again, need not be a misunderstanding of the ‘money festival’, but rather an earlier aition for the worship of Chrysus in the hippodrome. It may be true that the higher dating of the Pythiads, which Boeckh adopted from Paus., does not work so well for the victories celebrated by Pindar; but Menaechmus (if it was he) might have reckoned these victories a Pythiad later.

page 62 note 1 So Jacoby, (1904), pp.102–5, who refuted previous attempts to show how the eighth-yearly festival might come to be dated a year too early in the Pindaric scholia.Google Scholar

page 62 note 2 The assumption is made both in treatments of our chronological problem (so e.g. Cadoux, , JHS 68 (1948), 100–1CrossRefGoogle Scholar) and in studies of the calendar (e.g. Nilsson, M. P., Die Entst. und rel. Bedeut. des gr. Kal. 2, p. 47Google Scholar). On this subject Cadoux appears to fall into some confusion. To counter Jacoby's arguments for 591/0 as the date of the money festival, he suggests the ‘possibility that the aggression of the Kirrhaians had brought about a positive interruption of the religious calendar, and that a completely fresh start was made. Had this been the case, the date from which the new series of festivals ran might well have been that of the triumphal ![]() which, on this hypothesis, must have taken place in 590/89'. If the money festival fell in 590/89 (= 01. 47.3), no disturbance of the cycle need be postulated, for it is only marm. Par. A 37 that points to a different cycle from the Pythian Games. Nor would it be plausible to argue that whereas the money festival fell on the regular date of the old cycle, the second stage of the Sacred War displaced the first celebration of the Pythian Games and hence led to a new cycle; for the first Pythian Games came two years after the end of the War, and the old cycle could have been resumed in the interval; on this point, which he treats separately, Cadoux is quite mistaken (n.l, p.63 below).

which, on this hypothesis, must have taken place in 590/89'. If the money festival fell in 590/89 (= 01. 47.3), no disturbance of the cycle need be postulated, for it is only marm. Par. A 37 that points to a different cycle from the Pythian Games. Nor would it be plausible to argue that whereas the money festival fell on the regular date of the old cycle, the second stage of the Sacred War displaced the first celebration of the Pythian Games and hence led to a new cycle; for the first Pythian Games came two years after the end of the War, and the old cycle could have been resumed in the interval; on this point, which he treats separately, Cadoux is quite mistaken (n.l, p.63 below).

page 62 note 3 As to the month of the Pythian Games see Beloch, , Gr. Gesch. 2 i. 2.143.Google Scholar

page 62 note 4 It is sometimes held that the Pythian Ennaeteris was the first lunisolar calendar in Greece; and if so, the lunisolar date of the Olympic Games (which plainly follows an eighth-yearly cycle, coming after alternate intervals of forty-nine and fifty lunar months; must have been calculated from this calendar; but any date within the calendar was open to choice.

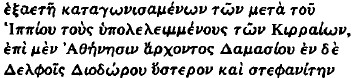

page 63 note 1 Hyp. b runs as follows, ![]()

![]()

![]() It is perfectly clear that the founding of the Pythian Games follows the end of the War by an interval of time,

It is perfectly clear that the founding of the Pythian Games follows the end of the War by an interval of time, ![]() the scholiast only neglects to specify the interval as

the scholiast only neglects to specify the interval as ![]() and his statement is not in the least ‘clumsily worded’, as Cadoux, , JHS 68 (1948), 100 n.153, contends, preferring the version of hyp. d. Hyp. d, much abbreviated, has indeed conflated the sixth-year victory with the founding of the Games, dating both events by the two archons; but this form of the scholium can be disregarded.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

and his statement is not in the least ‘clumsily worded’, as Cadoux, , JHS 68 (1948), 100 n.153, contends, preferring the version of hyp. d. Hyp. d, much abbreviated, has indeed conflated the sixth-year victory with the founding of the Games, dating both events by the two archons; but this form of the scholium can be disregarded.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

page 64 note 1 Nearly everyone: for Aly, (1950), pp.252–3, lays himself out to vindicate all these details.Google Scholar

page 64 note 2 Wilamowitz, (1893), i. 18Google Scholar n.29; Aly, (1950), p.252Google Scholar; Sordi, (1953), p.334 n.l.Google Scholar

page 64 note 3 For this reason it is hopeless to guess at the poem from which the fr. comes (Alexandras Meineke, Geranos Wilamowitz, ultimately from Rhianus' Thessalika through Euphorion's prose work On the Aleuads Hiller von Gaertringen, etc.).

page 64 note 4 In the two best manuscripts of D. the passage about Eurylochus and Parmenio was inserted inter ineas by the copyist, but its authenticity is not in doubt.

page 65 note 1 Though both anecdotes are certainly unhistorical, they show the associations of the name Eurylochus. D. L.'s anecdote, which represents Socrates as spurning the gifts and invitations of ‘Archelaus of Macedon and Scopas of Crannon (!) and Eurylochus of Larisa’, is plainly inspired by the famous passage of Plato's Crito, 53 d–54 a, and no doubt issues from the Socratic literature of the fourth century. The parergon of Lais seems to be modelled on the much more famous affair of Thargelia and Antiochus, which was handled by Aeschines the Socratic (fr. 23 Dittmar, cited by Philostr. Ep. 73). It seems likely then that both anecdotes employing Eurylochus grew up in the early or middle fourth century; together they suggest that Eurylochus was then a prominent name in Larisa.

page 65 note 2 Transactions between the Aleuads (or other nobles of Larisa) and the kings of Macedon before Philip are reported by Th. 4.78.2; [Herodes] Pol. 16–18; At.Pol. 5.10, 1311b17–20;and D. S. 15.61.3, 76.14.2.

page 65 note 3 From Satyrus' notice of Philinna and from the fact that her son Arrhidaeus was brought up as a prince, Beloch, , Gr. Gesch. 2 iii.2Google Scholar.69, reasonably deduced Aleuad lineage. The inference is contested by Westlake, H. D., Thess. in the Fourth Cent. B.C., p.168Google Scholar, on the grounds that Philinna is called a ‘dancer’ or a ‘harlot’ or a ‘worthless, common woman’ in our sources (collected by Berve, , Das Alexanderreich ii. 385Google Scholar n.4, who also takes them at face value); but such testimony, coming from historians of Alexander, is moonshine (cf. Hamilton on Plu, . Alex. 77.7).Google Scholar

page 66 note 1 At Front. 3.7.6 it is a strategem of Cleisthenes to introduce hellebore in Crisa's water-supply; this device goes back to Delphic legend (✶ VIII below), and may have been credited to Cleisthenes quite off-handedly, once he was linked with the War.

page 66 note 2 See n.2, p. 54 above.

page 66 note 3 It has been conjectured that Cleisthenes' chariot was kept in one of the two Sicyonian treasuries built in the first half of the sixth century; but perhaps any ancient-looking Sicyonian chariot would have set the story going.

page 67 note 1 Forrest, (1956), pp.41–2Google Scholar, 49–50, who holds that the curse was laid on the Alcmeonids by Delphi, and that the Sacred War was launched to chastise Delphi and Cirrha for past mistakes, is not surprised to find Alcmeon leading the Athenian contingent, for when Delphi was discredited, the Alcmeonids will have been rehabilitated. Whatever may be thought of this interpretation of events, it is not a sufficient answer; for as Forrest himself remarks, the Alcmeonids were forced into exile by a judicial verdict, not by a vague malaise; before Alcmeon could serve as general, the verdict must be reversed; and Forrest stops short of affirming that the verdict was so soon reversed, whether by the Solonian amnesty-law or by any other piece of legislation passed in or before 594/3– doubtless because he recognized that no memory could then survive of such a signal condemnation as Plu. describes at Sol. 12 A. And that Alcmeon could command Athenian troops while still in exile seems to me completely out of the question; Alcibiades, whom Forrest here invokes, gained authority on Samos for the very reason that the Athenians there were equally at odds with the home government.

page 67 note 2 Str. and Paus. likewise fail to distinguish the Alcmeonid temple from its fourth-century successor (whereas both are clear about the predecessor of the Alcmeonid temple, the building of Trophonius and Agamedes, which according to Paus. and others was destroyed in 548/7). It is misguided to infer, as some have done, that the legend retailed by ‘Thessalus’ must antedate 373/2, when the Alcmeonid temple was somehow laid in ruins. Pomtow, (1918), p.325, went much further, holding that the tale ignores the Alcmeonid temple as well, and hence must have reached the Asclepiads in its present form by the early or mid-fifth century, before Hdt. publicly announced the fact of the Alcmeonid reconstruction.Google Scholar

page 68 note 1 The only external indication of date comes from Erotian (med. s. I p.), who includes the Presb. in his list of Hp.'s works; to pass as authentic with Erotian, the speech ought to be distinctly older. On internal grounds the date of composition has been variously estimated. A strong current of opinion places it in the fourth century: so Herzog, R., Koische Forsch. und Funde, p.215Google Scholar, and again at RE vi A 1 (1936), 166Google Scholar, s.v. Thessalos; Pomtow, (1918), pp.326–7Google Scholar (late fourth century, after Thessalus' death); Roger, and van Effenterre, (1944), pp.16–17Google Scholar; Sordi, (1953), p.324Google Scholar (the work of ‘a Coan rhetor of the fourth century’); Bousquet, (1956), p.581Google Scholar (perhaps an authentic speech of Thessalus). But this dating is founded on preconceptions about the evidential value of the speech. The style is certainly later than the Classical period; Wilamowitz, (1922), p.73Google Scholar n.O, says ‘no doubt Late Hellenistic’, and Parke, (1957), p.277Google Scholar, concurs. If the Calydonian prerogatives at Delphi, which inspired the tale of Chrysus' friend from Calydon, were obtained during the Aetolian ascendancy, the speech cannot antedate the third century, and of course may be later. Edelstein, , RE Suppl. vi (1935), 1300–5, s.v. Hippokrates, holds that most of the Hippocratic legends reflected in the letters and speeches grew up in the second and first centuries B.C. The upshot is that the work is likelier to fall late than early in the Hellenistic period.Google Scholar

page 69 note 1 Since Leake this site has been mooted by Frazer on Paus. 10.37.4; by Pomtow, (1918), pp.330–1Google Scholar, who observes that the water needed for the horses could readily be brought here from the springs at Chrysó; and by Bousquet, (1956), pp.591–2, who publishes a dedication from the hippodromiGoogle Scholar

page 69 note 2 That the speech describes the site of Ay. Georghios (‘Crisa’ in the usual parlance) was recognized by Pomtow, (1918), pp.321Google Scholar, 330, and others. Sordi, (1953), pp.328–30, aware that archaeological evidence rules out any real connection between this site and the Sacred War, but believing the speech largely reliable, is put to the necessity of interpreting the remarks about the Crisaean stronghold as ‘an explanatory note of the rhetor of the fourth century’, who mistakenly identified the city of the Sacred War with the Crisa of early poetry, taking its ‘topographic position’ from Horn, and Pi. (But where are the topographic details in Horn, and Pi.?)Google Scholar

page 69 note 3 The redoubtable aspect of these ruins is best described by Frazer on Paus. 10.37.5 from whom I borrow details.

page 69 note 4 The hellebore of Parnassus, as also of Oeta and Helicon, is commended by Plin, . H.N. 25Google Scholar.49. Of course it is the port of Anticyra that figures as the staple source of hellebore in literature, but only because the medicinal form was here prepared and exported (cf. Str. 9.3.3; Plin, . H.N. 22Google Scholar.133, 25.52), and because some distinguished patients resorted here for treatment. The plant must have come from Parnassus; for although Paus. 10.36.7 assures us that it grew in plenty on the desolate crags above Anticyra, expert opinion cited by Frazer ad loc. pronounces this region quite unsuitable. When Polyaenus 6.13 speaks of the Amphictyons' fetching hellebore from Anticyra, we can only smile.

page 69 note 5 A pharmacist of Munich told Siewert, P., Der Eid von Plataiai (1972), p.77Google Scholar, that ‘no medicinal effect can be obtained by infusing hellebore in water that has not been heated'. Some have preferred to rationalize the tale, suggesting that the besiegers did not use hellebore at all, but introduced the waters of a salt-spring still existing some way east of the harbour town of Cirrha, for in the nineteenth century these waters were said to be valued locally as a purgative: so Wilamowitz, (1893), i. 18 n.29, and Frazer on Paus. 10.37.7.Google Scholar

page 70 note 1 At Olympia the hero bore the epithet Taraxippus, for which Paus. 6.20.15–9 offers a variety of explanations, most of them jejune and none identifying the hero as Ischenus, the name given by Lycophron and his sch.: the sch.'s aition will be earlier than any of Pausanias'.

page 70 note 2 The hero Glaucus at the Isthmus, otherwise mentioned only by Clem, . Alex. Strom. 1Google Scholar.21, 137, and perhaps implied by Nic, . Alex. 606, was inevitably said to be the son of Sisyphus, and so a substantial figure of legend; but it has often been observed that Sisyphus and his line belong to some other part of Greece and were probably first appropriated for Corinth in the body of epic poetry subsumed under the name ‘Eumelus’; and if so, the hero Glaucus at the Isthmus may antedate ‘Eumelus’ and may even have assisted the transposition.Google Scholar

page 70 note 3 According to Paus. the heroes at Olympia and the Isthmus, and the gleaming rock at Nemea, made the horses shy; Frazer on Paus. 6.20.15 records speculation that the horses were startled by their own shadows, suddenly cast in front of them as they rounded the track; and the name Chrysus, as denoting bright sunlight (cf. e.g. Pi. P. 4.144), might suit this idea. But Paus. 10.37.4 says that the Delphic hippodrome, in contrast to the Olympic, ‘is not apt to induce terror in the horses, either on account of a hero or for any other reason’; the conjectured site of the hippodrome is in fact partly shaded from the sun.

page 71 note 1 The right accorded to the Asclepiads appears as  in Littre's text, where the first word, otherwise unknown, was adopted by Littre' from a single manuscript with the sensible observation that the phrase is a high-flown equivalent of

in Littre's text, where the first word, otherwise unknown, was adopted by Littre' from a single manuscript with the sensible observation that the phrase is a high-flown equivalent of ![]() Other manuscripts give

Other manuscripts give ![]()

![]() both obvious mistakes, though the latter found favour with Hercher (Epistologr. Gr. 314)Google Scholar, who translated the phrase as praesentia ac scientia rerum futurarum! Other critics have worried the text, Pomtow, (1918), p.326Google Scholar, suggesting

both obvious mistakes, though the latter found favour with Hercher (Epistologr. Gr. 314)Google Scholar, who translated the phrase as praesentia ac scientia rerum futurarum! Other critics have worried the text, Pomtow, (1918), p.326Google Scholar, suggesting ![]() , and Bousquet, (1956), pp.584–5,

, and Bousquet, (1956), pp.584–5, ![]() All this represents a loss of ground since Littre.Google Scholar

All this represents a loss of ground since Littre.Google Scholar

page 71 note 2 Bousquet, (1956), pp.579–85Google Scholar, 593 = SEG XVI. 326Google Scholar = Sokolowski, , LSCG Suppl. 42Google Scholar, a decree of the koinon of Asclepiads of Cos and Cnidus posted at Delphi. According to Bousquet, (1956), pp.587–90Google Scholar, a Delphic decree honouring the Asclepiads (Fouilles de Delphes III, no. 394) soon followed, probably in the second quarter of the fourth century. Delphi has also yielded the remains of a four-line epigram on a votive base, with the names Thessalus and Hippocrates in the first line. The monument, said to be datable to the first half of the fourth century, is discussed by Pomtow, (1918), pp.307–16Google Scholar, and by Bousquet, (1956), pp.586–7; but Pomtow's interpretation, with reference to Paus. 10.2.6, is entirely fanciful.Google Scholar

page 71 note 3 The expression ![]()

![]() occurs both in the Asclepiad decree (n.2 above), lines 10–11, and in [Thessalus]’ speech. In the eyes of Bousquet, (1956), p.581Google Scholar, this proves the speech close in date to the inscription; but the phrase

occurs both in the Asclepiad decree (n.2 above), lines 10–11, and in [Thessalus]’ speech. In the eyes of Bousquet, (1956), p.581Google Scholar, this proves the speech close in date to the inscription; but the phrase ![]() is of course common in itself, and the significance of male descent was doubtless long remembered by the Asclepiads; a grave relief from Miletupolis in Phrygia, of the second century after Christ, describes the deceased as

is of course common in itself, and the significance of male descent was doubtless long remembered by the Asclepiads; a grave relief from Miletupolis in Phrygia, of the second century after Christ, describes the deceased as ![]() (Peek, , GVI i. 718, line 3, adduced by Sokolowski on LSCG Suppl. 42).Google Scholar

(Peek, , GVI i. 718, line 3, adduced by Sokolowski on LSCG Suppl. 42).Google Scholar

page 72 note 1 Apart from St. Byz. the clan-name Nebridae occurs only in Arn. Adv. nat. 5.39, where it seemingly denotes a class of Dionysiac worshippers at Eleusis (Demeter ‘honoured the Nebridae with the fawn-skin'), and so is perhaps a mistake for some ritual term like ![]() Whether the clanname derives from a real Nebrus, and whether it denotes a true kinship group, is impossible to know. Herzog, , SBAW 1928Google Scholar, no. 6, p.43, lists all the known gentilician names on Cos, including of course some patronymic forms; but none of the hypothetical forebears has a name like ‘Nebrus'. That descendants of Hp. should be named Draco is not surprising; the fawn however has no known significance in the cult of Asclepius. To my knowledge two historical bearers of the name Nebrus are attested–Nebrus son of Lysis in a subscription list at Cyrene, from the end of the fourth century (SEG XX. 735Google Scholar b I 91), and Nebrus son of Nebrus in another subscription-list on Cos, dated to c. 240 (Paton, W. R. and Hicks, E. L., The Inscr. of Cos, pp.277–9Google Scholar, no. 387, 1. 27, and pp.335–6). But the first instance as well as the second could be due to the celebrity of the Asclepiad Nebrus. The speculation about the origin of the clan canvassed by Wüst, E., RE xvi 2 (1935)Google Scholar, 2156, s.v. Nebridai, is not helpful; and few will be convinced by the nature symbolism which Kerenyi, K., Asklepios (1959), p.55, discerns in the pairing of Nebrus and Chrysus.Google Scholar

Whether the clanname derives from a real Nebrus, and whether it denotes a true kinship group, is impossible to know. Herzog, , SBAW 1928Google Scholar, no. 6, p.43, lists all the known gentilician names on Cos, including of course some patronymic forms; but none of the hypothetical forebears has a name like ‘Nebrus'. That descendants of Hp. should be named Draco is not surprising; the fawn however has no known significance in the cult of Asclepius. To my knowledge two historical bearers of the name Nebrus are attested–Nebrus son of Lysis in a subscription list at Cyrene, from the end of the fourth century (SEG XX. 735Google Scholar b I 91), and Nebrus son of Nebrus in another subscription-list on Cos, dated to c. 240 (Paton, W. R. and Hicks, E. L., The Inscr. of Cos, pp.277–9Google Scholar, no. 387, 1. 27, and pp.335–6). But the first instance as well as the second could be due to the celebrity of the Asclepiad Nebrus. The speculation about the origin of the clan canvassed by Wüst, E., RE xvi 2 (1935)Google Scholar, 2156, s.v. Nebridai, is not helpful; and few will be convinced by the nature symbolism which Kerenyi, K., Asklepios (1959), p.55, discerns in the pairing of Nebrus and Chrysus.Google Scholar

page 72 note 2 Eurybatus son of Euphemus, though descended from the R. Axius, is described as ![]() and the land of the Kouretes, in this context, can only be Aetolia. Aetolia and Macedon are linked again in mythical genealogies at Paus. 5.1.5, 4.4.

and the land of the Kouretes, in this context, can only be Aetolia. Aetolia and Macedon are linked again in mythical genealogies at Paus. 5.1.5, 4.4.