Article contents

Notes on Chronological Problems in the Aristotelian ἈΘΗΝΑΙΩΝ ΠΟΛΙΤΕΙΑ

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 11 February 2009

Extract

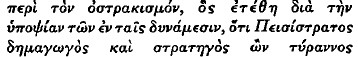

It is obvious that A.P. attached importance to chronology and considered it his business to supply his sketch of Athienian constitutional development, at every stage, with such chronological indications as were available. Thus his account of Peisistratos (14 ff.) largely follows Herodotus (1. 59 ff.), but with the addition of a more detailed chronology of the tyrant's comings and goings (and some other matter derived from the Atthidographers). From the archonship of Solon to that of Xenainetos he has constructed what is evidently intended to be a continuous chronological chain, by marking the intervals between events.

Information

- Type

- Research Article

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Classical Association 1961

References

page 31 note 1 I propose to use this abbreviation to refer to the treatise and its author indifferently. I do not intend to go into the question of authorship. That the work belongs to the Aristotelian corpus, no one, of course, diputes. Hignett, C. in his History of the Athenian Constitution (1952), pp. 27 ff., has lately challenged the generally accepted attribution to Aristotle himself, and has restated the opinion that the work was written by one of Aristotle's pupils. A decision on the autiiorship question is not essential to the discussion of A.P.'s chronology. The question crops up at one point: the discrepancy between A.P. and Aristotle, Politics 1315b29 ff., on the chronology of Peisistratos and his sons (see pp. 39, 41 f. below). The discrepancy is unimportant and easily accounted for, and it is immaterial whether the pupil or the master is amending what was said in the Politics.Google Scholar

page 31 note 2 Cf. Jacoby, F., Atthis (1949), pp. 152 ff., 188 ff.Google Scholar

page 31 note 3 Names appearing without other indication are those of archons. Only archons given in A.P. are listed. Dates are added where no reasonable doubt about diem can exist. (See especially Cadoux, T. J. on ‘The Athienian Archons from Kreon to Hypsichides’, J.H.S. lxviii (1948), 70 ff., where some of the archondates up to 481/o are fixed definitively and the determination of others is facilitated by clear and careful discussion.) I have added the relevant references in A.P. Dotted lines, the absence of a line, and questionmarks, indicate the existence of problems of various kinds about the chronological links concerned.Google Scholar

page 33 note 1 Wilamowitz-Kaibel, ed. 2 (1891), ad loc.

page 33 note 2 Cf. Jacoby, , Atthis, p. 379Google Scholar, n. 141, Cadoux, , op. cit., p. 83, n. 50 on use of numeral signs in A. P.Google Scholar

page 33 note 3 483/2 for Nikodemos is given by Dion. Hal. A.R. 8. 83. 1, and follows from A.P. 22 when this chapter is interpreted correctly. The facts are established beyond question by Cadoux, , op. cit., p. 118Google Scholar. It is not necessary to repeat his demonstration (cf. also Hignett, , op. cit., pp. 336–7Google Scholar) that![]() cannot be explained by connecting it with the ostracism of Aristeides (22. 7 fin.) and then dating the ostracism to 484/3 instead of 483/2. Cf. also Labarbe, J., La loi navale de Thémistocle (1957), pp. 87 ff.Google Scholar

cannot be explained by connecting it with the ostracism of Aristeides (22. 7 fin.) and then dating the ostracism to 484/3 instead of 483/2. Cf. also Labarbe, J., La loi navale de Thémistocle (1957), pp. 87 ff.Google Scholar

page 33 note 4 Wilamowitz-Kaibel, ad loc.; cf. Wila- mowitz, Aristoteles und Athen (1893), i. 25; Cadoux, Hignett, locc. citt. (previous note).Google Scholar

page 33 note 5 Cf. How and Wells, , Commentary on Herodotus, ii. 262 (ad 8. 79. 1).Google Scholar

page 33 note 6 Cf. Busolt, , Gr. Gesch. ii 2. 673–4Google Scholar, n. 9. The earlier dates proposed by Labarbe, J., op. cit., PP. 91–93Google Scholar, n. 3 (cf. B.C.H. 1954, pp. 20–21), viz. 24 July to mid-August, are open to the objection that die interval left between Xerxes' arrival in Attica and the battle of Salamis is improbably long.Google Scholar

page 34 note 1 The decree of amnesty is mentioned, without exact date, by Andocides, , Myst. 107 ff., cf. 77. Philochoros refers (F.G.H. F 30) to the new regulation prohibiting the ostracized from residing![]() (cf. A.P. 22. 8).Google Scholar

(cf. A.P. 22. 8).Google Scholar

page 34 note 2 Cf. 4. 1; 14. 1, 3; 17. 1; 19. 6; 21. 1; 22. 2, 3, 5; 23. 5; 25. 2; 26. 3, 4; 27. 2; 32. 1, 2: 33. 1. 34. 1, 2; 35. 1; 39. 1; 39. 1; 40. 4; 41. 1. 54. 7. The only other exception is at 22. 7 where the Berlin papyrus has![]()

![]() (confirmed as to the name by Dion. Hal. 8. 83. 1), but the London papyrus reads

(confirmed as to the name by Dion. Hal. 8. 83. 1), but the London papyrus reads![]() There is no chronological difficulty, but the discrepancy about the name, and the omission of

There is no chronological difficulty, but the discrepancy about the name, and the omission of![]() ,arouse suspicion of interpolation. The excision of the phrase would make no difference to the sense. If it is retained,

,arouse suspicion of interpolation. The excision of the phrase would make no difference to the sense. If it is retained,![]() ought definitely to be read before

ought definitely to be read before![]()

page 34 note 3 The omission of![]() and the order

and the order![]() are characteristic of some later practice as seen, for example, in Marmor Parium and Dion. Hal. A.R. (passim). Of course Hypsichides is to be rejected only from the text of A.P., not from the archonlist, where he evidently belongs in the year 481/0. (This interpolation is the only testimony to his existence.)

are characteristic of some later practice as seen, for example, in Marmor Parium and Dion. Hal. A.R. (passim). Of course Hypsichides is to be rejected only from the text of A.P., not from the archonlist, where he evidently belongs in the year 481/0. (This interpolation is the only testimony to his existence.)

page 35 note 1 Cf. Philochoros, , F.G.H. F 116Google Scholar; Plut, . Cato Maior 5.Google Scholar

page 35 note 2 Herod. 8.95. Cf.Bury, J. B., C.R. x (1896), 414 ff.Google Scholar

page 35 note 3 Probably to convey Athenian refugees (Grundy, , Great Persian War [1901], p. 390Google Scholar) rather than to fetch the Aeacidae (Bury, loc. cit.); cf. How and Wells, , op. cit. ii. 262.Google Scholar

page 35 note 4 Cf. Busolt, , Gr. Gesch. ii 2. 680, n. 1.Google Scholar

page 35 note 5 Cf. ibid. 703, n. 3.

page 36 note 1 See Cadoux, , op. cit., p. 116Google Scholar; cf. Hignett, , op. cit, p. 337.Google Scholar

page 36 note 2 Cf. Schachermeyr, F., Klio, 1932, p. 347, on which Hignett, loc. cit.Google Scholar

page 36 note 3 Kenyon, ed. 2 (1891), p. 57.

page 36 note 4 Gomme, A. W., J.H.S. xlvi (1926)Google Scholar, 176n. 12, mentions the possibility of a lacuna here; cf. also his Commentary on Thucydides, i. 132.Google Scholar

page 37 note 1 Stated thus, the third solution escapes the criticisms of Hignett, (op. cit., p. 337, cf. 159), who does not take into account the possibility of a lacuna. It may be added that in rejecting the evidence of A.P. in favour of his interpretation of a fragment of Androtion (F.G.H. F 6) preserved by Harpokration, Hignett (pp. 159 f.) disposes too easily of the high probability that Harpokration is not quoting verbatim but summarizing from![]() and in the process has garbled the meaning; and that what Androtion wrote was not

and in the process has garbled the meaning; and that what Androtion wrote was not![]()

![]()

![]() but is to be recovered precisely from A.P. 22. 3— Tore [488/7]

but is to be recovered precisely from A.P. 22. 3— Tore [488/7]

![]()

![]() Hignett does not consider this point, but is content to demolish the obviously untenable view that Harpokration is really misquoting A.P. If the point is taken, the alleged conflict between the sources withers away.Google Scholar

Hignett does not consider this point, but is content to demolish the obviously untenable view that Harpokration is really misquoting A.P. If the point is taken, the alleged conflict between the sources withers away.Google Scholar

page 37 note 2 See Schachermeyr, , R.E. xix. 1Google Scholar, s.v. Peisistratos, esp. 171 ff.; Jacoby, , Atthis, esp. pp. 370–80Google Scholar, nn. 95–151; most recently Heidbüchel, F., ‘Die Chronologie der Peisistratiden in der Atthis’, Philologus ci (1957)Google Scholar, 70 ff., giving a conclusive refutation of Jacoby's reconstruction in Atthis, pp. 188–96.Google Scholar

page 37 note 3 See below, p. 40, n. 3.

page 38 note 1 See below, p. 48, n. 4.

page 38 note 2 I refer to Jacoby's remark in Atthis, p. 194.Google Scholar

page 38 note 3 A. Bauer's proposal (Lit. u. hist. Forsch. Zu Arist.![]() [1891], p. 50Google Scholar) to read f

[1891], p. 50Google Scholar) to read f![]()

![]() meaning the 12th year from the first usurpation is unacceptable: (a) this is contrary to A.P.'s system (cf. Jacoby, , Atthis, p. 378, n. 135); (b) it makes the combined exiles too long (16 years).Google Scholar

meaning the 12th year from the first usurpation is unacceptable: (a) this is contrary to A.P.'s system (cf. Jacoby, , Atthis, p. 378, n. 135); (b) it makes the combined exiles too long (16 years).Google Scholar

page 38 note 4 Cf. Gomme, , J.H.S. xlvi (1926), 173Google Scholar f., 177. For the assumption here challenged see, e.g., Jacoby, , Atthis, p. 128Google Scholar; Heidbüchel, , op. cit., pp. 84Google Scholar ff. The majority of scholars cited by Schachermeyr, , R.E., loc. cit. 171 f. accept![]() (See further p. 44 below.)Google Scholar

(See further p. 44 below.)Google Scholar

page 39 note 1 Cf. Sandys, ed. 2 (191 a), pp. xlix ff.

page 39 note 2 See further p. 41, n. 3, pp. 41 f., and p. 46 below.

page 39 note 3 Cf. p. 42, n. 2 below.

page 39 note 4 This rather pedestrian calculation hai to be set out in full because of the tendency of some scholars to turn a blind eye towards it. Jacoby, (Atthis, p. 190Google Scholar) goes so far as tc claim agreement between A.P. and Herodotus in making the 19 years part of the ‘uninterrupted rule of Peisistratos and his sons’ (i.e. 36 years from 546/5 to 511/10 incl.); cf. Herod. 5. 65. 3—r![]()

![]() That A.P. does not do this has been adequately demonstrated by Heidbüchel, , op. cit., pp. 79Google Scholar, 88. Hammond, N. G. L. (C.Q. n.s. vi [1956], 51) supports a view similar to Jacoby's by a special interpretation of

That A.P. does not do this has been adequately demonstrated by Heidbüchel, , op. cit., pp. 79Google Scholar, 88. Hammond, N. G. L. (C.Q. n.s. vi [1956], 51) supports a view similar to Jacoby's by a special interpretation of![]()

![]() in 17. 1—that it means ‘remained continuously’ (in power). So it might, in other contexts, but it does not have to, and the rest of what A.P. says shows that it cannot do so here.Google Scholar Aristotle, Pol. 1315b29 ff., reveals the same kind of calculation as is found in A.P. He says: the Peisistratid tyranny ‘was not continuous, for Peisistratos was twice exiled during his tyranny

in 17. 1—that it means ‘remained continuously’ (in power). So it might, in other contexts, but it does not have to, and the rest of what A.P. says shows that it cannot do so here.Google Scholar Aristotle, Pol. 1315b29 ff., reveals the same kind of calculation as is found in A.P. He says: the Peisistratid tyranny ‘was not continuous, for Peisistratos was twice exiled during his tyranny ![]() so that in 33 years he ruled as tyrant for 17 of these years, and his sons ruled 18 years, so that the total

so that in 33 years he ruled as tyrant for 17 of these years, and his sons ruled 18 years, so that the total ![]() amounted to 35 years’. This can only mean that the 17 years of rule, like A.P.'s 19 years, were spread over three periods of tyranny. See further pp. 44 ff. below.

amounted to 35 years’. This can only mean that the 17 years of rule, like A.P.'s 19 years, were spread over three periods of tyranny. See further pp. 44 ff. below.

page 39 note 5 The alternative of 6, 7, and 6 years can be ruled out: (a) because A.P. counts inclusively with ordinal numbers, so that 6 would be represented by![]() not

not![]() and 7 by

and 7 by![]() not

not![]() (b) because the last period was regarded as the main period of tyranny (Herod. 1. 64. 1; A.P. 15. 3), and the descriptions of the earlier periods as of not much duration (A.P. 15. 1; Herod. 1. 60. 1) evidently imply that the last period was thought of as the longest.

(b) because the last period was regarded as the main period of tyranny (Herod. 1. 64. 1; A.P. 15. 3), and the descriptions of the earlier periods as of not much duration (A.P. 15. 1; Herod. 1. 60. 1) evidently imply that the last period was thought of as the longest.

page 39 note 6 Cf. Cadoux, , op. cit., p. 109Google Scholar. Jacoby, , Atthis, p. 371, n. 99, confuses matters unecessarily.Google Scholar

page 40 note 1 Cadoux, , op. cit., pp. 104 ff.Google Scholar

page 40 note 2 Cf. p. 42, n. 2 below. Cf. also Hammond in Historia iv (1955), 382, on this mode of reference.Google Scholar

page 40 note 3 So already Wilamowitz, A. u. A. i. 23. Cf. Ed. Meyer, , Forsch. z. alt. Gesch. ii. 244Google Scholar: ‘eine andere Zahl ist hierfúr nicht möglich’. Heidbüchel, , op. cit., p. 85, n. 3, is justified in observing: ‘Man kann sich nur wundern dass die späteren Editoren diese völlig sichere Emendation nicht in den Text aufgenommen haben.’Google Scholar

page 40 note 4 Similarly Wilamowitz, A. u. A. i. 23; Heidbüchel, , op. cit. p. 86. However, it is preferable not to base the argument on the dubious figure of 49 years in A.P. 19. 6 (cf. the next part of the discussion).Google Scholar

page 41 note 1 Cf. Cadoux, , op. cit. pp. 112 f.Google Scholar

page 41 note 2 Cf. Jacoby, , Atthis, pp. 373–4Google Scholar, n. 107. Heidbüchel, , op. cit., p. 77, cf. 86, retains, with Wilamowitz, the figure 49 and attributes it to ‘doppelt exklusive Rechnung’. But A.P. does not use such reckoning.Google Scholar

page 41 note 3 P. 39 above. There may also be the intention to correct the similar calculation made in the Politics ![]()

![]() (cf. p. 39 n. 4 above).

(cf. p. 39 n. 4 above).

page 41 note 4 Op. cit., pp. 83 ff.

page 41 note 5 Schol. Aristoph. Vesp. 502, presumably referring to this passage in A.P., notes![]()

![]() Whether it is his text that is corrupt, or he is using a corrupt text of A.P., his version probably derives ultimately from a reading

Whether it is his text that is corrupt, or he is using a corrupt text of A.P., his version probably derives ultimately from a reading![]() in A.P. 19. 6. But this of course proves nothing as to the correctness of the reading, only that the mistake was not confined to our papyrus. Jacoby (cf. n. 2 above) would read

in A.P. 19. 6. But this of course proves nothing as to the correctness of the reading, only that the mistake was not confined to our papyrus. Jacoby (cf. n. 2 above) would read![]() both in A.P. and in the scholiast; but this is not satisfactory because A.P. usually counts exclusively with cardinal numbers (cf. p. 42, n. 2 below), and it would be odd for A.P. to get 51 from the sum of 33 (17. 1) and 17 (19. 6). If die usual interpretation is retained (implying that A.P. uses the word

both in A.P. and in the scholiast; but this is not satisfactory because A.P. usually counts exclusively with cardinal numbers (cf. p. 42, n. 2 below), and it would be odd for A.P. to get 51 from the sum of 33 (17. 1) and 17 (19. 6). If die usual interpretation is retained (implying that A.P. uses the word![]() loosely), the simplest correction would be to read

loosely), the simplest correction would be to read![]() in A.P. This would have at least the advantage of consistency: die 33 added to the 17 years giving a total of 50, and the exclusive mode of reckoning being used consistently. It would also agree with Eratos-thenes' figure

in A.P. This would have at least the advantage of consistency: die 33 added to the 17 years giving a total of 50, and the exclusive mode of reckoning being used consistently. It would also agree with Eratos-thenes' figure![]() (Schol. Ar. Vesp. loc. cit.). After the misreading of the v as paragogic, die process of restoration would have proceeded as suggested.

(Schol. Ar. Vesp. loc. cit.). After the misreading of the v as paragogic, die process of restoration would have proceeded as suggested.

page 42 note 1 Cf. p. 47 below.

page 42 note 2 The Politics reckons the years of tyranny of Peisistratos' sons inclusively (18 years), but the period from Peisistratos' usurpation to his death exclusively (33 years). This was clearly necessary, since to reckon both periods inclusively would have meant counting the same year (538/7) twice. A.P. generally uses exclusive reckoning with cardinal numbers (cf. 13. 1; 32. 3, 6; and below). Inclusive reckoning is used at 32. 2![]() (i.e. 511/10–413/11). But here he is following Thucydides 8. 68. 4

(i.e. 511/10–413/11). But here he is following Thucydides 8. 68. 4![]() and there is a natural preference for the retention of the more impressive round century. At A.P. 25. 1 exclusive reckoning is probably used:

and there is a natural preference for the retention of the more impressive round century. At A.P. 25. 1 exclusive reckoning is probably used:![]()

![]() i.e. 479/8–462/1. His previous timenote was Timosthenes' archonship, 478/7 (23. 5). But both Herodotus and Thucydides count

i.e. 479/8–462/1. His previous timenote was Timosthenes' archonship, 478/7 (23. 5). But both Herodotus and Thucydides count![]() as ending in 479(/8): cf. Hammond's note on Thucydides' usage, C.R. n.s. vii (1957), 100–1. A.P. apologizes for the resulting imprecision with

as ending in 479(/8): cf. Hammond's note on Thucydides' usage, C.R. n.s. vii (1957), 100–1. A.P. apologizes for the resulting imprecision with![]() The apparently unnecessary

The apparently unnecessary![]() in 19. 6, where the reckoning is exclusive, may be due to the fact that 18 years was the figure usually given for the tyranny of Peisistratos' sons (cf. the Politics) and A.P. anticipates cavil at his deviating from the established figure (which he has to do in order to conform to Herodotus' 36 years).Google Scholar

in 19. 6, where the reckoning is exclusive, may be due to the fact that 18 years was the figure usually given for the tyranny of Peisistratos' sons (cf. the Politics) and A.P. anticipates cavil at his deviating from the established figure (which he has to do in order to conform to Herodotus' 36 years).Google Scholar

page 42 note 3 Cf. pp. 46 f. below.

page 42 note 4 Cf. Jacoby, , Apollodors Chronik, p. 193Google Scholar. Attempts to show that there were other traditions seem unsuccessful. According to Kaletsch, H., ‘Zur lydischen Chronologie’, Historia vii (1958), 1–47Google Scholar, although the Christian chronographers give 546/5, Apollodoros' (and Sosikrates') date was 547/6. This depends on the assumption that Thales' death and the fall of Croesus and Sardis were assigned to the same (Olympic) year. But the reference in Diog. Laert. (1. 37–38) seems to show that the date of Thales' death was got from what was apparently regarded as his last activity—the diversion of the Halys at the outset of Croesus' Cappadocian campaign. Hence there is no need to make a difference between the Hellenistic and the Christian chronographers. The Cappadocian campaign can begin in spring-summer (547/)546, continuing into 546(/5), and the fall of Sardis follows in 546/5. Kaletsch also (p. 23) gives Herodotus' dates for Croesus as 560–547. This overlooks two points: (a) Herodotus reckons by archon-years, (b) his 14 years for Croesus (1.91) imply termination in the 15th; see Hammond, , ‘Studies in Greek Chronology (etc.)’, Historia iv (1955), pp. 371 ff., who, however, becomes confused in his calculations, giving Herodotus' date for Croesus' accession as 559/8 (whence would follow 545/4 for the fall of Sardis) and Herodotus' date for Gyges' accession as 711/10 (whence would follow 541/0 for Sardis' fall). Herodotus' dates for Croesus are more probably 560/59–546/5.Google Scholar Kaletsch rightly rejects (pp. 40–41) the supposed evidence of Xanthos (F.H.G. i. 43Google Scholar; cf. Euphorion, ap. Clem. Alex, . Strom. p. 399Google Scholar P., Pliny, N.H. 35. 35Google Scholar) for a tradition of 541/0 for the end of Croesus' reign. The supposed evidence of the Marmot Parium for such a tradition should also be rejected. The missing date in ep. A 42 (fall of Sardis) cannot legitimately be restored by calculating from ep. 41 (mission of Croesus to Delphi, 292 years from Diognetos, i.e. 555/4, cf. Cadoux, , op. cit., pp. 108Google Scholar f.). If the Parian had meant to refer to Croesus' accession in ep. 41, he must surely have done so explicitly. The item evidently comes from Delphic records (cf. epp. 37, 38) and has nothing to do with Croesus' accession or calculations about the dating of his reign. The supporting argument from the coincidence that the interval between ep. 41 (292 years from Diognetos) and ep. 35 (accession of Alyattes, 341 years from D.) is equal to the interval between the accessions of Alyattes and Croesus in Eusebius (49 years), falls to the ground when we observe that in M.P. this is due to the shift from exclusive to inclusive reckoning (cf. Cadoux, , op. cit., pp. 83 ff.); the true interval for M.P. is 50 years (605/4–555/4). Finally, the reference to Hipponax' floruit in ep. 42 is scarcely a sufficient foundation for fixing a date for the fall of Sardis. I conclude that we do not know M.P.'s date for this event, but that there is nothing to prevent it from having been the 546/5 of the rest of the tradition.Google Scholar The evidence of the Babylonian Nabunaid chronicle (cf. Weissbach, in R.E. Sup. v [1931]Google Scholar, Kroisos 457, Kaletsch, , op. cit., pp. 43 ff.) scarcely affects the question of the Greek tradition. But it is doubtful whether it supports the date 547 for the fall of Croesus and Sardis, since there are no solid grounds for identifying Croesus as the defeated king mentioned but not extant by name in the chronicle for 547, and some ground for not doing so since this king is recorded as killed by Cyrus.Google Scholar

page 43 note 1 Not 546/5. Cf. previous note and pp. 45 f. below; also Gomme, , J.H.S. xlvi (1926), 174Google Scholar; Jacoby, , Atthis, pp. 371 f., n. 100.Google Scholar

page 43 note 2 But actually the implication is more probably the division of the ‘Attic nation’ by the exile of Peisistratos' opponents after Pallene (1. 64. 3).

page 43 note 3 Another factor may well have been the need to date the Battle of Pallene as late as possible, so as to allow for Hegesistratos' participation in it (A. P. 17. 4); cf. p. 48, n. 2 below.

page 44 note 1 Jacoby, , Atthis, p. 376, n. 115, would dismiss the story as obviously unhistorical. There are other reasons for childlessness, he remarks. But then we should have to abandon also Herodotus' explanation of the tyrant's behaviour as a deliberate piece of dynastic policy: yet as such it makes perfectly good sense.Google Scholar

page 44 note 2 But the story, if used for chronology, does not compel us to restrict the period to months (as Pomtow, , Rh. Mus. li [1896], 561Google Scholar f.; cf. Jacoby, , Atthis, pp. 191Google Scholar, 375–6, 11. 115). Wilamowitz's 2 years seem a reasonable maximum (A. u. A. i. 23).Google Scholar

page 45 note 1 Hammond, in Historia iv (1955), 384 f., argues that the 4 years are reckoned exclusively, and therefore dates the expulsion of the tyrants to 510/9. From this would follow 546/5 for Pallene, and 545/4 for the fall of Sardis. He further argues that when Thucydides (6. 59. 4) says Hippias ruled for 3 years after the death of Hipparchos, his rule coming to an end in the fourth year, this can be reconciled with Herodotus' statement on the assumption that Thucydides is reckoning by seasonal years, not archon-years. Hipparchos was killed at the Panathenaea of 514 (28 Hekatombaion); in the fourth year (28 Hekatombaion 511 to 27 Hekatombaion 510) Hippias was deposed. Combined with the date 510/9 inferred from Herodotus, this gives a very precise dating, for Hippias' deposition, namely, the first month of the archon-year 510/9 (Hekatombaion 510).Google Scholar This argument seems to raise more difficulties than it solves. It entails that Thucydides was able to date the fall of tyranny precisely to the first month of the Athenian civil year 510/9. How could he do this unless he knew under what archon the tyranny fell ? If he knew that the event took place under the archon of 510/9, it is difficult to see how this knowledge could have eluded the researches of the Atthidographers, who placed the event firmly in the archonship of Harpaktides, 511/10 (A.P. 19. 6; Marm. Par. ep. A 45). It may also be noted that Plato (Hipparch. 229 b), presumably counting in the orthodox manner by archon-years, says that the Athenians were under tyranny for 3 years after Hipparchos' death; which, in effect, corrects Herodotus. A.P. himself indicates puzzlement over Herodotus' 4 years. At 19. 2 he dates the deposition of Hippias![]()

![]() But this does not lead him to doubt the date of the deposition, which he firmly sets in the archonship of Harpaktides. What it does do is to inhibit him from giving an exact date (archon-date) for Hipparchos' assassination. Finally, the cost of Hammond's interpretation of Herodotus' 4 years includes not only the abandonment of the firm archon-date for the end of the tyranny but also the acceptance of an unsupported date for the fall of Sardis. These criticisms do not affect Hammond's view that Thucydides is reckoning by seasonal years, which I accept, while modifying the detailed application. Thucydides does date the end of the tyranny to the year between 28 Hekatombaion 511 and 27 Hekatombaion 510, but with the other evidence we can contract the latter terminal to the end of Skirophorion 510 (end of 511 /10). In the remaining words of 6. 59. 4, Thucydides does not date the Battle of Marathon in the 20th year from Hippias' expulsion. He dates Hippias' departure from the court of Darius to join the Marathon expedition to the 20th year from his arrival at that court after being expelled from Athens and after first going to Sigeion and Lampsakos. This allows a much greater margin of time than Hammond accounts for. Assuming that Hippias left Susa in spring 490, his arrival can be pushed back as far as spring (511/) 510, and a fortiori there is no difficulty about putting his departure from Athens in 511/10.

But this does not lead him to doubt the date of the deposition, which he firmly sets in the archonship of Harpaktides. What it does do is to inhibit him from giving an exact date (archon-date) for Hipparchos' assassination. Finally, the cost of Hammond's interpretation of Herodotus' 4 years includes not only the abandonment of the firm archon-date for the end of the tyranny but also the acceptance of an unsupported date for the fall of Sardis. These criticisms do not affect Hammond's view that Thucydides is reckoning by seasonal years, which I accept, while modifying the detailed application. Thucydides does date the end of the tyranny to the year between 28 Hekatombaion 511 and 27 Hekatombaion 510, but with the other evidence we can contract the latter terminal to the end of Skirophorion 510 (end of 511 /10). In the remaining words of 6. 59. 4, Thucydides does not date the Battle of Marathon in the 20th year from Hippias' expulsion. He dates Hippias' departure from the court of Darius to join the Marathon expedition to the 20th year from his arrival at that court after being expelled from Athens and after first going to Sigeion and Lampsakos. This allows a much greater margin of time than Hammond accounts for. Assuming that Hippias left Susa in spring 490, his arrival can be pushed back as far as spring (511/) 510, and a fortiori there is no difficulty about putting his departure from Athens in 511/10.

page 46 note 1 Heidbüchel, , op. cit., p. 79.Google Scholar

page 46 note 2 Cf. Jacoby, , Atthis, pp. 371–2, n. 100. Herodotus' howler in connecting Croesus and Solon (1. 29 ff.) can also serve as a dreadful warning.Google Scholar

page 46 note 3 Jacoby, , Atthis, p. 334, n. 22, expresses scepticism on this, but his opinion seems to fluctuate (cf. p. 364, n. 69, where Aristion's motion and the date appear to be treated as documentary).Google Scholar

page 46 note 4 The distinction that Jacoby, (Atthis, p. 186) insists on with regard to this point seems to be an unprofitable quibble. Naturally A. P. dates the important event, the occupation of the Acropolis by Peisistratos (with bodyguard), since this marks the beginning of the tyranny.Google Scholar

page 46 note 5 The case of A.P. 19.2 is also illuminating (see p. 45, n. 1 above).

page 47 note 1 So Cadoux, , op. cit., p. 107. But his suggestion that A.P. may have made a mistake in attaching the archonship of Hegesias to the first instead of to the second expatriation is unacceptable. Both Herodotus and A.P. clearly indicate that whereas Peisistratos was expelled the first time, he went voluntarily into exile on the second occasion, because of fear of what was being plotted against him. A decree of banishment is therefore more appropriate for the first expatriation. Cadoux's inference from Herod. 1. 61. 2, that Peisistratos did not leave Attica when he was expelled (1. 60. 1:![]() ) seems most implausible. We may compare the implication of

) seems most implausible. We may compare the implication of![]() and

and![]() (A.P. 14. 4; 15. 1).Google Scholar It is not necessary to repeat Cadoux's refutation (op. cit., p. 108) of the notion that Hegesias may be identified with the archon ol 560/59, Hegestratos (Pomtow, , Rh. Mus. 1 [1895]. 575Google Scholar; Jacoby, , Atthis, pp. 193, 378, n. 133).Google Scholar

(A.P. 14. 4; 15. 1).Google Scholar It is not necessary to repeat Cadoux's refutation (op. cit., p. 108) of the notion that Hegesias may be identified with the archon ol 560/59, Hegestratos (Pomtow, , Rh. Mus. 1 [1895]. 575Google Scholar; Jacoby, , Atthis, pp. 193, 378, n. 133).Google Scholar

page 47 note 2 Cf. Jacoby, Atthis, p. 364, n. 69.Google Scholar

page 47 note 3 Cf. p. 45, n. 1, and p. 46, n. 5 above.

page 47 note 4 See p. 44, n. 2 above.

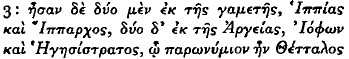

page 47 note 5 An inference from the word-order in 17. (cf. 18.1; Thuc. 6.55; on Hippias' seniority). The problem of Hegesistratos' nomenclature is tangential to the present discussion, but it seems worth while offering the suggestion that Thessalos was his correct name and Hegesistratos the sobriquet

(cf. 18.1; Thuc. 6.55; on Hippias' seniority). The problem of Hegesistratos' nomenclature is tangential to the present discussion, but it seems worth while offering the suggestion that Thessalos was his correct name and Hegesistratos the sobriquet![]() being a name given in honour of his ‘leading the army’ from Argos to the battle at Pallene. The name Thessalos is confirmed as the official name of one of the Peisistratids by the inscription cited by Thucydides (6. 55. 1). The description of Hegesistratos as

being a name given in honour of his ‘leading the army’ from Argos to the battle at Pallene. The name Thessalos is confirmed as the official name of one of the Peisistratids by the inscription cited by Thucydides (6. 55. 1). The description of Hegesistratos as![]() (Herod. 5. 94. 1) looks like nothing more than a reflection of contemporary propaganda, of which the reference to Timonassa as

(Herod. 5. 94. 1) looks like nothing more than a reflection of contemporary propaganda, of which the reference to Timonassa as![]() is perhaps another echo. The idea that the tyrant's sons by Timonassa were officially illegitimate is not credible. To suppose that Thessalos and Hegesistratos were different and distinct persons (cf. Schachermeyr, in R.E. xix. 1Google Scholar, Peisistratidae 152 ff.) is to infer that the Atthis did not know how many sons the tyrant had; which is incredible. In fact, A.P. is confident

is perhaps another echo. The idea that the tyrant's sons by Timonassa were officially illegitimate is not credible. To suppose that Thessalos and Hegesistratos were different and distinct persons (cf. Schachermeyr, in R.E. xix. 1Google Scholar, Peisistratidae 152 ff.) is to infer that the Atthis did not know how many sons the tyrant had; which is incredible. In fact, A.P. is confident![]() and well informed on the subject (we should not know of Iophon but for him). Jacoby's suggestion (Atthis, p. 378, n. 133) that Hegesistratos might be identified with Hegestratos, archon 560/59 (whom he wants to identify also with Hegesias, archon 556/5; cf. n. 1 above), seems very wild.Google Scholar

and well informed on the subject (we should not know of Iophon but for him). Jacoby's suggestion (Atthis, p. 378, n. 133) that Hegesistratos might be identified with Hegestratos, archon 560/59 (whom he wants to identify also with Hegesias, archon 556/5; cf. n. 1 above), seems very wild.Google Scholar

page 48 note 1 The word used by A.P.![]() is evidently borrowed from Herod, i. 61. 4, where it is applied to Lygdamis:

is evidently borrowed from Herod, i. 61. 4, where it is applied to Lygdamis:![]()

page 48 note 2 Those who placed Peisistratos' Argive marriage in his first exile (A) and who dated Hegesistratos' birth, consequently, not earlier than 555/4 or 554/3, had a powerful motive for dating the Battle of Pallene to 536/5. This may have been a further factor influencing A.P.'s adoption of this date (cf. p. 43, n. 3 above).

page 48 note 3 Die Tyrannis in Athen (1929), pp. 5 ff. His dates are 561/0, 556/5 or 555/4, 552/1, 551/0, 541/0, etc. But he wrongly read![]()

![]() at A.P. 14. 4, and furthermore 552/1 is not the fourth year from 556/5 nor is it the third from 555/4.Google Scholar

at A.P. 14. 4, and furthermore 552/1 is not the fourth year from 556/5 nor is it the third from 555/4.Google Scholar

page 48 note 4 A. u. A. i. 22 ff. His dates are: 561/0, 556/5, 553/2 551/0. 541/0. etc. He rightly read![]() at A.P. 14. 4, but 553/2 is not the fifth year from 556/5.Google Scholar

at A.P. 14. 4, but 553/2 is not the fifth year from 556/5.Google Scholar

page 49 note 1 Cf. Jacoby, , Apollodors Chronik, p. 167.Google Scholar

page 49 note 2 Forsch. z. Ar.![]() pp. 45Google Scholar f.; cf. Jacoby, , Atthis, p. 346Google Scholar, n. 22, p. 365, n. 71; Cadoux, , op. cit., pp. 93Google Scholar ff.; Hignett, , op. cit., p. 317.Google Scholar

pp. 45Google Scholar f.; cf. Jacoby, , Atthis, p. 346Google Scholar, n. 22, p. 365, n. 71; Cadoux, , op. cit., pp. 93Google Scholar ff.; Hignett, , op. cit., p. 317.Google Scholar

page 49 note 3 The parallels cited by Jacoby, (Ap. Chron. p. 171, n. 14) are of course of this type.Google Scholar

page 49 note 4 Cf. also p. 38 above.

page 49 note 5 Cf. Meritt, B. D., Hesperia viii (1939), 59 ff.Google Scholar

page 49 note 6 Schol. Ar. Pax 347:![]() (sc. Phormion)

(sc. Phormion)![]()

![]() There is hardly scope for equivocation about the meaning of

There is hardly scope for equivocation about the meaning of![]() in this formula (cf. Cadoux, , op. cit., p. 99).Google Scholar

in this formula (cf. Cadoux, , op. cit., p. 99).Google Scholar

page 49 note 7 Phil, . Vit. Soph. 1. 16. 2:![]()

![]() Google Scholar

Google Scholar

page 49 note 8 Cf. Schmid-Stählin 4. 1. 2. 116.

page 49 note 9 Plato, Timaeus, 20 e.

page 50 note 1 Polybius 12. II. i.

page 50 note 2 Schol. vet. in Pindari Carmina; Hypoth. Pyth. (Drachmann ii. 1–5Google Scholar) b, d; cf. Cadoux, , op. cit. pp. 99 ff.Google Scholar

page 50 note 3 Several scholars have seen the necessity of interpreting A as above, but have apparently failed to see diat B can be interpreted in the same sense without the violence of taking![]() as exclusive reckoning or otherwise ignoring its precise terms: cf. Bauer, , op. cit., pp. 45Google Scholar ff.; Wilamowitz, A. u. A. i. 10Google Scholar; Busolt, , Gr. Gesch. ii 2. 301Google Scholar, n. 3; Sanctis, De, Atthis 2, pp. 204Google Scholar ff.; Beloch, , Gr. Gesch. i 2. ii. 161 ff.Google Scholar

as exclusive reckoning or otherwise ignoring its precise terms: cf. Bauer, , op. cit., pp. 45Google Scholar ff.; Wilamowitz, A. u. A. i. 10Google Scholar; Busolt, , Gr. Gesch. ii 2. 301Google Scholar, n. 3; Sanctis, De, Atthis 2, pp. 204Google Scholar ff.; Beloch, , Gr. Gesch. i 2. ii. 161 ff.Google Scholar

page 51 note 1 Cadoux, , op. cit., p. 94, cf. p. 95, n. 121, who nevertheless accepts the interpretation on the ground that ‘it is difficult to see what else the Greek can possibly mean’.Google Scholar

page 51 note 2 As supposed by L. J. D. Richardson, ap. Cadoux, , op. cit, p. 95Google Scholar, n. 121, and Jacoby, , Atthis, p. 351, n. 46. Clearly, too, this interpretation of 13. 2 will not square with the precise interpretation of 13. 1 proposed above. For if year I = 594/3, then![]() 589/8 and 584/3, and Damasias 579/8–577/6. If year I = 592/1, then

589/8 and 584/3, and Damasias 579/8–577/6. If year I = 592/1, then![]() 587/6 and 582/1, and Damasias 577/6–575/4. Neither of these dates for Damasias is reconcilable with our other information on him.Google Scholar

587/6 and 582/1, and Damasias 577/6–575/4. Neither of these dates for Damasias is reconcilable with our other information on him.Google Scholar

page 51 note 3 ‘Still within the same period’— von Fritz, K. and Capp, E., Aristotle's Constitution of Athens, p. 80, but their interpretation of ‘the same period’; as the whole Solon-Komeas period (p. 158, n. 30) seems very improbable.Google Scholar

page 51 note 4 Cf. Jacoby, , Atthis, p. 175Google Scholar; Cadoux, , op. cit., p. 102.Google Scholar

page 52 note 1 Dion. Hal. 3. 36. 1 records an earlier Damasias for 639/8.

page 52 note 2 Cf. Cadoux, , op. cit., p. 102, n. 162.Google Scholar

page 52 note 3 Cf. Lysias 7. 9; A.P. 35. 1; 41. 1; Jacoby, , Atthis, pp. 174–5, 351. in. 48–50.Google Scholar

page 52 note 4 Cf. Cadoux, , op. cit., pp. 85, 102 n. 162.Google Scholar

page 52 note 5 Cited p. 50, n. 2 above.

page 52 note 6 Diog. L. 1. 22 (F.G.H. 228 F 1).

page 52 note 7 Op. cit. p. 102.

page 52 note 8 Professor Andrewes justly points out that the argument that Demetrios would not Dmit the qualification![]() could only be pressed if we had Demetrios' actual words.

could only be pressed if we had Demetrios' actual words.

page 53 note 1 Clem, . Alex. Strom. i. 127. 1; Synkellos (Dind.) 1, p. 429.Google Scholar

page 53 note 2 M.P. ep. A 37 (327 years from 264/3; cf. Cadoux, , op. cit., pp. 99 ff.). It follows that the supposed insertions would have been made already by 264/3.Google Scholar

page 53 note 3 ap. Diog. Laert. 1. 101.

- 5

- Cited by