Article contents

Orestes and the Argive Alliance

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 11 February 2009

Extract

Tragic allusions to contemporary events are not, as a rule, taken on trust, but the Eumenides of Aeschylus provides three notable exceptions. The view that the Athenian-Argive alliance of 462 B.C. (Thuc. 1. 102. 4, Paus. 4. 24. 6–7) is reflected in Eum. 287–91, 667–73, anc^ 762–74 has won wide acceptance, although no systematic theory of the relation between the drama and the historical context has yet been advanced. If demonstration in detail has been wanting, the view seems to be supported by three general considerations. In the first place, the emphasis put on the dramatic declaration of friendship exceeds the requirements of the plot: the acquittal of Orestes rather than his gesture of gratitude to Athens is the natural climax of this part of the drama, 1–777, and yet the gesture has been considered important enough to be heralded twice before it is actually made in 762–74. Secondly, Orestes' declaration is not limited in duration but binding on his successors in perpetuity; it seems, therefore, to have been deliberately formulated in order to react upon historical fact. Thirdly, in instituting the Council of the Areopagus and dwelling upon the importance of its constitutional function (see especially 681–710), Aeschylus seems to have gone out of his way to pass judgement of some sort on the recent reforms of Ephialtes and Pericles; the theory that he has also appreciated their foreign policy on the tragic stage is thus relieved of some of the obvious practical objections and made inherently more plausible.

- Type

- Research Article

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Classical Association 1964

References

page 190 note 1 Dindorf rejected 767–74 as an interpolation dating to the Peloponnesian War, but more recent editors have rightly refused to follow him; despite the inroads of textual corruption the whole passage has an authentic ring. Thomson, n. on 765–7 (his numeration), strikes a note of caution: ‘It seems more likely that Aeschylus is merely availing himself of a contemporary event in order to add point to a profession of eternal gratitude which is appropriate to the dramatic situation’. But this, if I understand it aright, is tantamount to conceding the connexion.

page 190 note 2 Like Dover, K. J., ‘The Political Aspects of Aeschylus's Eumenides’, J.H.S. lxxvii (1957) 230–7, I see no evidence in the play that Aeschylus gave only qualified approval to the democratic programme.Google Scholar

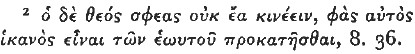

page 191 note 1 Construe ![]() with

with ![]() and not, as Verrall does, with

and not, as Verrall does, with ![]() …

… ![]() , and cf. Eum. 1025.

, and cf. Eum. 1025.

page 191 note 2 For temporal ![]() see Cho. 684, Eum. 83, 401, 891 ; Groeneboom .p. 99 n. 4.

see Cho. 684, Eum. 83, 401, 891 ; Groeneboom .p. 99 n. 4.

page 192 note 1 'The Danaid Tetralogy of Aeschylus', J.H.S. lxxvii (1957), 221.Google Scholar

page 194 note 1 Jebb's note, as distinct from his translation, which obscures the issue, ascribes to Antigone a non sequitur of the kind ‘even if human sympathy fails me, let me acquire you as witnesses’.

page 194 note 2 For ![]() of a god cf. Cho. 2 and 19.

of a god cf. Cho. 2 and 19.

page 195 note 1 Groeneboom is wrong to include the Argives, who have been adequately covered by ![]() .

.

page 195 note 2 So Dobree conjectured ![]() for the manuscripts'

for the manuscripts' ![]() . at Eum. 381.

. at Eum. 381.

page 195 note 3 Thuc. I. 107. 5—108. 1,I.G. i. 931/932 (cf. Meritt, , ‘The Argives at Tanagra’, Hesp. xiv [1945], 134–47). iCrossRefGoogle Scholar

page 195 note 4 ![]() , Thuc. 1. 105. 2.

, Thuc. 1. 105. 2.

page 195 note 5 Thuc. 1. 111. 1.

page 196 note 1 The oath sworn by Aegeus to Medea in Eur. Med. 746–54 is only a personal guaran-tee, and even then Aegeus has not made the ![]() explicit (755).

explicit (755).

page 197 note 1 For ![]() cf. I.G. i. 14/15. 52–55, cited on p. 200 below.

cf. I.G. i. 14/15. 52–55, cited on p. 200 below.

page 197 note 2 Compare ![]() , Eum. 683, 1031, with

, Eum. 683, 1031, with ![]() , Eum. 708, Pers. 526.

, Eum. 708, Pers. 526.

page 197 note 3 C.R. viii (1894), 301–2.Google Scholar

page 197 note 4 On Cho. 1029 (Cambridge, 1901).

page 197 note 5 See Zuntz, G., The Political Plays of Euripides, pp. 88–94.Google Scholar

page 197 note 6

page 198 note 1 See Paus. 2. 20. 2.

page 199 note 1 See Frazer on Paus. i. 28. 5 and Thomson on Eum. 685.

page 199 note 2 ![]() has been derived with some probability from

has been derived with some probability from ![]() by Wachsmuth, C., Die Stadt Athen, i. 428 n. 2,Google ScholarG.Gilbert, , Griech. Staatsalterthümer, i. 425n. 4.Google Scholar This al ternative, if it was familiar to the Athenians, could not be accepted by Aeschylus without embarrassing the theme of the second part of the Eumenides.

by Wachsmuth, C., Die Stadt Athen, i. 428 n. 2,Google ScholarG.Gilbert, , Griech. Staatsalterthümer, i. 425n. 4.Google Scholar This al ternative, if it was familiar to the Athenians, could not be accepted by Aeschylus without embarrassing the theme of the second part of the Eumenides.

page 199 note 3 Line 693, ![]()

![]() , is the crucial point. Here one can only marvel at the waywardness of the emendators. For the vox nihili of the manuscripts at least seven conjectures have been proposed, including such recherché items as

, is the crucial point. Here one can only marvel at the waywardness of the emendators. For the vox nihili of the manuscripts at least seven conjectures have been proposed, including such recherché items as ![]() and

and ![]() , but never the commonplace

, but never the commonplace ![]() , a thoroughly Aeschylean word which, if we place a full stop immediately after

, a thoroughly Aeschylean word which, if we place a full stop immediately after ![]() , gives admirable sense. Of the rest

, gives admirable sense. Of the rest ![]()

![]() is the best (so Dover), but it is adding laws (cf.

is the best (so Dover), but it is adding laws (cf. ![]() ., 694), not changing laws, which suits the context, and

., 694), not changing laws, which suits the context, and ![]() cannot be Athena's enactment, for that is called elsewhere only

cannot be Athena's enactment, for that is called elsewhere only ![]() ,

, ![]() (484, 491, 571, 615) because it is made by a deity and institutes a permanent constitutional body (see 484, 572). The

(484, 491, 571, 615) because it is made by a deity and institutes a permanent constitutional body (see 484, 572). The ![]() of

of ![]() elsewhere has intensifying force, and this is not excluded here (‘provided that the citizens do not ratify laws on their own initiative’), but the sense ‘additionally’, frequent in other compounds, should be preferred. For

elsewhere has intensifying force, and this is not excluded here (‘provided that the citizens do not ratify laws on their own initiative’), but the sense ‘additionally’, frequent in other compounds, should be preferred. For ![]() of legislation cf. Suppl. 608, 622, 942–3, 964–5 and

of legislation cf. Suppl. 608, 622, 942–3, 964–5 and ![]()

![]() , Eum. 391–2. This interpretation would confirm the view that the powers removed from the Council in 462 B.C. had been acquired constitutionally and that the democrats did not deny it.

, Eum. 391–2. This interpretation would confirm the view that the powers removed from the Council in 462 B.C. had been acquired constitutionally and that the democrats did not deny it.

page 200 note 1 I.G. i. 26. 9–13; cf. Tod, , Greek Historical Inscriptions, i. 39,Google ScholarMeritt, , A.J.P. lxix (1948), 312–14,Google ScholarS.E.G. x. 18.

page 200 note 2 I.G. i. 14/15. 52–55. An execration of this sort is evidently envisaged for the ratification of the Peace of Nicias by Thuc. 5. 18. 9.

page 201 note 1 Hdt. 5. 76 omits it from the list of ‘Dorian Invasions of Attica’.

page 201 note 2 See now Huxley, G. L., Early Sparta (London, 1962), pp. 67–87.Google Scholar

page 202 note 1 Poralla, , Prosopographie der Lakedaimonier, pp. 45–46.Google Scholar

page 202 note 2 This seems to be the nucleus of the argu ment used against the Spartans in 481 B.C. (Hdt. 7. 148. 4); see Diamantopoulos, loc. cit.

page 202 note 3 The Spartans accepted the tradition that Orestes married Hermione and ruled at Lacedaemon, being succeeded by his son Tisamenus (Paus. 2. 18. 5–6, 7. 1. 8).

page 203 note 1 See Thomson's note, referring to Din. 1. 9, Lycurg. Leocr. 52, and Dem. 23. 70.

page 204 note 1 See Apollo's ![]()

![]() , 668, Athena's address to the

, 668, Athena's address to the ![]() , 949, and 687–8.

, 949, and 687–8.

page 204 note 2

page 205 note 1 So Dover concludes, from the historical evidence.

page 205 note 2 See Huxley, pp. 77–96.

page 206 note 1 Wilamowitz, , Hermes lxiv (1929), 461–2.Google Scholar

page 206 note 2 In preparing this article I have profited by the criticisms of Professor K. J. Dover and Dr. W. Ritchie, but I must be held solely responsible for the views expressed and for any errors which remain.

- 8

- Cited by